- Millie

There’s something always safe about old women

- Dawn

Except for Snow White

In the original Snow White , far from Disney’s portrayal of a wicked stepmother, it was Snow’s own mother who wanted to eat her heart and lungs. The gruesome image of a mother eating the organs of her own child is thought to be an historical remnant of a time when families starving to death considered killing or abandoning their children (Tatar 1987). Other fairy tales, like Hansel and Gretel , have similar themes, however, some versions became considered unsuitable for young readers and the tales were sanitised. The mother in Snow White , for instance, instead became a stepmother. This chapter, while it does not discuss the eating of hearts is about young people’s emotional worlds in relation to story. Challenges arise on a daily basis for teachers and schools to meet the needs of students from various backgrounds. How different families manage emotion has implications in the classroom for not only facilitating cooperation between groups of people from different backgrounds, but also to support different learning needs. In the UK around 20,000 young people a year are placed outside of the main stream education system in pupil referral or alternative provision/education units due to a variety of reasons including: teenage pregnancy, behavioural issues, physical and mental health issues (Department for Education 2015). The aim is to later reintroduce them back into main stream education. From a purely academic perspective, only 1.4% of these students obtained five or more A* to C (or 4 to 9) grades at GCSE level compared to 53% of students (in English schools). While in Scotland, special schools or units are attached to individual schools (Education Scotland 2018). As undertaking standard tests may not be appropriate no performance data is provided for special schools. In any case grades indicate nothing about how students may have improved their life skills in other areas. GCSE results remain an unfair criterion to judge these alternative provision schools on, when pupils often arrive with unmet learning needs. It would be more useful to discern what young people’s learning levels are at various entry and exit points because it is a real achievement for a previously failing student to obtain a D to G (or 3 to 1) grade.

In terms of alternative provision, twenty-four recommendations for improvements have been made to the Department of Education for all students (Remsbery 2012). I felt struck by the language used to refer to young people’s educational needs. Words used included ‘quality’, ‘effective assessment’, ‘intervention’, ‘targets’ and ‘managing pupils’ behaviour’. None of the recommendations acknowledged young people’s emotions. It is my argument that acknowledging different emotional backgrounds is important to understand and accommodate the needs of all students, after all, as I began to demonstrate in the last chapter schools request that students manage their behaviour, and associated emotions, such as anger. What outcomes does focusing on educational targets over emotions have on our children’s education?

- 1.

People emotionally, mentally or physically interact with a text: ‘we touch, sense, perceive, vocalize, or perform a text with our eyes, hands, mouths, and bodies’

- 2.

Actions occur during the act of reading such as ‘holding a book close like a charm for comfort or protection, or touching or kissing reverentially a page in a prayer book’

- 3.

Responses to text include a wide ‘range of emotional, spiritual, somatic responses readers have to a text, such as crying, laughing, becoming angry, or becoming aroused’ (2001, pp. 6, 83).

You walk down the street, and see a barking dog. How do you feel?

Take a moment to reflect how you feel and why: are you curious, anxious, delighted, unsure? I heard the above example from a US teacher in Minneapolis. The teacher noticed a large proportion of the class had responded to the question above with ‘happy’ during an English test. ‘This system is failing the children,’ she explained, ‘these were children whose families couldn’t afford pets so naturally they felt excited and happy when imagining seeing a dog.’ She raised this inconsistency with the school, but the proper response she was told was ‘afraid’, and the other students’ responses had to be marked as incorrect. The teacher believed, that this instance was a good example of the way in which the structure of questions in class assessments made less privileged students in her class more likely to fail. A situation she fought to challenge simply by providing more context in the way in which the question was asked. A description of the dog as angry or agitated for example, would indicate in a clearer way that it would be dangerous to approach, leading to the correct answer.

Some of the challenges of education involve the benefits and/or costs of the rational-emotion divide used to justify correct and incorrect answers. We need to ask who do these divides assist or obstruct? Is it possible to make educational assessment inclusive regardless of gender, ethnicity, class, and so on? (Goodley 2007; Zembylas 2016). This chapter demonstrates storytelling is one way to provide a space in schools for young people to explore their connections to story through emotion. I will show it is a space where they can share ideas and learn from each other, and most importantly learn that all of their opinions and emotions matter.

How Emotions Were Discussed Following Storytelling

- 1.

The result of the interaction between the body and its surroundings

- 2.

Experienced and interpreted within an individual

- 3.

Social constructions with different meanings in different countries

Debates include, although it is not an extensive list: the extent to which emotions are socially constructed and/or socially organising (Hochschild 2012; Burkitt 2014), the gendering of emotion (Simon and Nath 2004; Erickson 2005; Shields et al. 2006) and how emotional expression differs because of ethnicity and other factors such as class or chronic illness (Skeggs 2009; Ahmed 2010; Hoppe 2013; Burkitt 2014). Two important works in the sociology of emotions are Arlie Hochschild’s The Managed Heart and the work of Thomas Scheff (1990, 2000, pp. 96–97, 2011, pp. 68–77). Scheff asserts that shame is an important social emotion because it is a response to the threatening and strengthening of social bonds.

As the classification of emotions and feelings is a contested issue, emotions and feelings were not separated in this study and included states of mind such as sympathy because feelings could be indicative of a complex emotional response. I identified emotions and feelings by observing the students’ use of language in the storytelling space.

- 1.

Storyteller performance

- 2.

A performer-audience relationship

- 3.

As students discussed emotions in the stories

- 4.

When students compared personal emotional experience

- 5.

During group conflict

- 6.

In different locations and circumstances

I will use examples to describe each of these aspects in turn.

Storyteller Performance

Her husband had been away for many, many years fighting in the war. One day he trudged home in a foul, foul, foul mood. She got everything ready for him: she got the house redecorated, she got all the favourite foods he liked, all that sort of stuff. Trying to give him the best welcome possible. But he was just in this awful, awful mood. He wouldn’t really speak to her. He refused to go into the house cause he’d been so used to sleeping on stone for so long (Alex)

Her husband was fighting a war for a very long time. So finally the husband returned but this time he refused to get back into the house and he’s always angry at her. So he did not live in the house he’d rather live in the forest because he’s so used to sleep on the stones. She was so excited when he heard about the husband returning she did shopping, she cooked, she prepared this fresh white soybean curd, some different kinds of fish, some different kinds of seaweed and some rice. She happily bring all the food to the husband but the husband stood up and he kicked away the bowl! (Michelle).

Note that only Miriam said ‘soldier’. She used the words: ‘terrible things’, ‘anger’, ‘scared’ and ‘confused’ to express what the husband felt and experienced. Miriam also compared the husband’s personality before and after experiencing war. On the other hand, Michelle focused on the husband’s actions from the wife’s point of view: she was ‘excited’ and ‘happy’ while he acted ‘angry’ towards her. The final storyteller, Alex, referred to an ‘awful mood’ and the wife’s preparations for her husband’s homecoming. His description was the least emotional of the three storytellers.He was a soldier and so it happened that there was a war and he had to go away. He was away for a really long time. The wife missed him terribly, but eventually, a few years later, it was time for him to come home. Now when he’d been at war he’d seen some terrible things, and he’d done terrible things, and he’d lost people. And he was angry, and he was scared and confused, and he didn’t know how to be the gentle, kind, loving husband that he’d been before […] He’d got so used to being outside and sleeping on the rocks that he wouldn’t come into the house (Miriam)

- Olive

Like if they, if they killed somebody

- Holly

Killed a friend by accident

- Ava

Or they see their best friend killed, Hunger Games!

- Olive

Or they killed a German wife by accident, and then he feels really bad

Alex had not mentioned in detail what the husband saw during the war, yet the students inferred what the husband’s experience of war might have been like—thus filling in the emotional gaps. The group connected the soldier’s experience to their lives through other stories, such as the films Hunger Games and War Horse mentioned above, while other groups connected his experience to: family via a relative who had ‘flashbacks’ and ‘bad dreams’; and connections to the army through a stepdad, stepbrother and a family friend.

Their use of medical terms, like post-traumatic stress disorder, and second-hand experience through family and education, indicated that the students understood to some extent the potential hardships and emotional consequences of war. The students used this knowledge to fill in the emotional gaps left by each storyteller’s narrative regardless of different telling styles.

A Performer Audience Relationship -

In the story She-Bear the queen made the king promise not to marry again unless they were as beautiful as her, or she would ‘curse’ him from beyond the grave. After a grieving period, the king realised he needed an heir to the throne. He had all the beautiful women in the world line up, then turned to his daughter and proposed marriage to her; of course, she ‘severely reproved and censured’ him for the idea! (Basile 1983).

He’d made a promise to his wife that he’d only marry the next beautiful woman to her […] He would go around playing all these women off each other, a sort of horrible display of, I don’t know, misogyny […] It was then when he realised, rather strange I should point out, ‘Why should I spend all this time searching all over the globe, for the next woman, when I’ve got someone just as beautiful as her in my own house?’ [Laughs] You’re right, he’s got the daughter. (Alex)

‘When I die you shall not remarry otherwise I will cast a curse upon you’ […] He cried so bitter, he was screaming, he pulled out his hair, his moustache! […] ‘I will marry someone who is as beautiful as her so this new queen can bear me a son’ […] He was worried that he could not find a new queen for his kingdom, and then he had this thought all of a sudden. He thought, ‘My beautiful daughter is just here. She looks exactly like her mother. I could just marry her and let her bear a son for me.’ (Michelle)

When Alex performed at Pentland he hesitated, tripping over his tongue, pausing to find the right words as he framed the story for his audience. Alex appeared to be embarrassed as a male telling this story in an all-female school. This embarrassment was demonstrated by how Alex focused on the misogynistic nature of the king’s actions to prepare his audience. Alex hesitated, and took care to explain that what he was about to say was ‘strange’. His hesitation implied a social expectation of how this incestuous act would be received. In contrast, Michelle did not hesitate. She framed the story through the queen’s curse, the king’s grief and the rational decision that he needed an heir to the throne. Michelle carried the listener through the king’s changing emotions. She set up her narrative to surprise the listener when the king’s eyes rested on his daughter.

During Alex’s performance one student, Ava, responded with disbelief, ‘His daughter?’ Alex laughed, and the students joined him. Alex continued telling the story in a less hesitant manner when the story’s immoral twist had been revealed. In Michelle’s group, an awkward silence followed the moment of surprise. Several students looked at other people for their reaction, until Bo whispered, ‘That’s just wrong!’ and everyone laughed, breaking the tension. So while Alex and Michelle framed the story differently, laughter dispersed awkward feelings and tension created by the king’s immoral choice of wife.

The performance-audience relationship affected the students’ interpretations of the king’s emotions. Alex’s rational performance led to rational-emotional interpretations. Felicity said she felt ‘happy’ because the princess was empowered to say ‘I’m not going to do that. It’s my life, my rules’. Holly imagined the king would feel ‘horrible’ and ‘embarrassed’ because ‘it’s not normal to marry your daughter’. Michelle’s more emotional performance resulted in comments such as, ‘It’s not really an emotional story’. Instead, the groups that saw Michelle’s performance talked about the reasons for the marriage. Amir said, ‘He only wanted to marry his daughter to get a-’; ‘-a wife’ David interrupted. The students had been supplied with the emotions of the characters by Michelle, which appeared to have prevented them imagining, or connecting to, the emotions of the characters. Gaps appear to be needed in a performance for the audience to feel the story.

A Managed Heart in Relation to Storytelling

A young businessman said to a flight attendant, “Why aren’t you smiling?” She put her tray back on the food cart, looked him in the eye and said, “I’ll tell you what. You smile first, then I’ll smile.” The businessman smiled at her. “Good,” she replied. “Now freeze, and hold that for fifteen hours” (Hochschild 2012, p. 127).

Taking this idea further, Hochschild questioned the effects of customer service training on the feelings of individuals by considering the influence of work-based training on people’s ‘private’ emotional interactions (2012, p. 76).

Also included in Hochschild ’s concept of emotional labour were the terms feeling and framing rules. You might recall from Chap. 2, where Mark fell out with his group, that feeling rules ‘guide emotion work by establishing the sense of entitlement or obligation that governs emotional exchanges’ (2012, p. 56). These rules become apparent in social contexts when a gap is sensed between what we should feel, and what we actually feel, such as a new mother suffering from depression during pregnancy which can be in conflict with social expectations of a joyful new arrival to the family. In many instances one could see how feeling rules then change depending on the surrounding culture. You may have come across what seemed like unusual local customs on your own travels. Just like local customs, emotional rules can vary within a country following the guidelines learnt and shared by others of the same gender, ‘age, religion, ethnicity, occupation, social class and geographical locale’ (Hochschild 2012, p. 262).

We understand feeling rules to be formed by framing rules: rules on what to feel are determined by rules on how one frames given situations. Framing rules are in turn informed by general phenomena such as gender ideologies or, even broader, commercialization. (Tonkens 2012, p. 200)

An example of a framing rule would be how people identify a problem and the concerns it raises, such as the effects of a new mobile phone mast on the surrounding community. Hochschild ’s work is relevant to storytelling with young people because it provides a way of thinking about how social practices inform the ways in which young people understand and utilise emotion.

One major criticism of her theory is that Hochschild paints an overly bleak picture of emotional labour by overemphasising the psychological and physical cost of emotional management and underestimating the satisfactions (Bolton and Boyd 2003). The point of Hochschild ’s work was to question viewing emotional labour as a “normal” part of social structures. The examples that she used demonstrated how individuals were pressured by organisations to conform, and also how they resisted conforming via their emotions—as in the earlier example of the flight attendant. It’s not all negative because Hochschild ’s concept supports the idea of continuous interactions between the constraining effects of structures and the empowering effects of agency via the management of emotion .

One strength of Hochschild ’s research is that questions are raised about the use of emotion in society. Hochschild ’s work has subsequently been applied to different workplaces (Yin et al. 2013; Pinsky and Levey 2015), and political and family contexts (Hochschild and Machung 2012). Yet Hochschild ’s theories are more broadly applicable than this because they provide a means that we can use to thematically consider young people’s emotion during group discussions following storytelling.

Discussions of Emotions in the Stories

To continue with the ways in which emotions arose in the storytelling space, some conversations about emotion arose from the students asking one another, ‘How does the story make you feel?’ Themes that arose included: the emotional and material concerns surrounding emotional or financial neglect; issues of trust between young people and adults, such as selfishness observed in certain character’s actions in the stories; the students expressed empathy for characters; and talked about the importance of thinking of others where the outcomes of one’s choices have an impact on other people.

It definitely makes you frustrated , you really want to be there to tell them you’re making the wrong decision: the king married the witch, the children are disrespected, the children leave home, the witch turns them into seals. There’s so many bad choices in the story.

Mark felt ‘frustrated’ that the children were ‘disrespected’. The children were in a powerless position, their future determined by ‘bad choices’ taken by parental figures. Different groups discussed how actions which stemmed from bad choices had an emotional impact on dependent family members, such as children and partners. The selkie could not return to the sea when the fisherman stole her pelt, Dawn said that it was ‘selfish of the man’ to take the woman’s pelt to ‘make his life better’. Actions and choices were perceived to have emotional impacts on others. The woman married the fisherman, but stared at the sea every day, grieving for the company of her siblings who remained seals.

Students’ views on the theft of the pelt were consistent across all six groups: stealing and lying were not moral acts . Peter said the story ‘had a moral’ because ‘you shouldn’t always trust someone’. Lucy said, ‘I wouldn’t steal the skin.’ Amy agreed, ‘Yeah, it’s not yours, so you shouldn’t take it, ruining someone’s life’. It was not viewed as moral to make decisions that had a negative impact on others’ emotions. Thus moral emotions informed actions. The students’ discussions of bad choices involved understanding emotions in the story, or their own emotions in response to the story, such as the selkie’s grief for her pelt or Mark’s frustration about the choices of parental figures in MacCodram .

- Olive

Okay, it makes me feel, I don’t know really cause stories, some stories, like reality stories they can make you feel

- Holly

They make it up, a bear wouldn’t talk to a human would he?

- Olive

Yeah, you can’t really feel anything, cause it would be entertaining for you. But you can’t really feel what the lady’s feeling, it’s not really real

- Holly

You can, sort of, you can tell that she feels

- Olive

Like she feels, desperate

- Holly

It hasn’t happened in your own life so you can’t really tell how it feels, you can tell how she feels, but you can’t tell how you feel cause you’re never in that situation

I will continue to illustrate how the students’ interpretations of characters’ emotions were linked to the student’s own responses to issues of emotional and material worries, i.e. financial neglect, in Chap. 5. For now, this section illustrates that young people discussed a complex range of emotions in relation to the stories, and felt willing to do so following storytelling which may be of use in situations such as group therapy by a trained professional after an incident at school, or simply to enable a space for students to share experiences in order to relate to one another. There is a whole field of study involving trauma and storytelling, as my work was not therapeutically-based I do not go into this but I would encourage interested readers to read The Healing Art of Storytelling by Richard Stone as a starting point.

Comparing Personal Emotional Experiences

Touching again on morals, the students’ morals and values seemed to be adaptable during different social situations involving emotion. Discussing jealousy, Olive said, ‘I did some stuff against [friends] cause I’m jealous […] little things like steal stuff from them. Steal stuff from my brother’. Olive attempted to adjust the powerless feeling of jealousy through the subversive behaviour of stealing, thus empowering herself: albeit in a socially unacceptable way. Olive said that stealing was wrong and potentially had other options to deal with her jealousy, but chose, or felt motivated, to steal more than once, indicating that this behaviour may have worked to moderate her feelings.

Mary’s patience was determined by her tolerance levels regarding a) the desire to get something done, such as downloading music, or b) the desire to go out and do something else. When Mary wanted to go out, her patience for downloading music decreased which suggested that Mary’s emotional labour required motivation. As an example related to motivation Mary, Paris and Heidi talked about their parents picking them up late from school.If it’s something I really want, then I could do. I’m quite patient. If it’s just something small […] I want to get it over and done with cause it’s getting on my nerves. If I’m downloading music and it’s taking for-ever, forever, and in five minutes I have to go out, so I’m like, ‘Hurry up’

- Mary

My mum was stuck in traffic and I was stuck outside Pentland for half an hour

- Heidi

That must have been awkward

- Mary

It was very awkward

- Paris

Me and Gray were waiting outside Pentland when it was snowing cause my gran was like, ‘Yeah, I’m coming now,’ so we walked from Gray’s cause she didn’t know where Gray’s was, we walked to Pentland and were waiting outside for an hour cause she got stuck in traffic. Snowing, so we waited outside for an hour while it was snowing

- Heidi

The amount of times I’ve waited outside the school for twenty minutes and then my dad says, ‘Oh, I’m late back from work. You’re going to have to walk back,’ and I was, ‘Are you being serious?’

Mary had a close relationship with her mother—who raised her as a single parent. This close mother-daughter bond, expressed in conversations over five weeks, enabled Mary to view the situation as one which neither party was in control of. Hence, Mary used phrases such as ‘mum was stuck’ and ‘I was stuck.’ Paris used phrases such as ‘she didn’t know’ and ‘she got stuck in traffic’, indicating that if her gran had been more organised, Paris and her friend could have waited at her friend’s house. Heidi felt similarly frustrated by her dad’s consistent lateness. This indicated that relationships between people influenced motivation and the level of emotional labour invested in the relationship was based on what young people perceived they owed others; which, if we recall from Chap. 3, Hochschild called ‘gift exchange’.

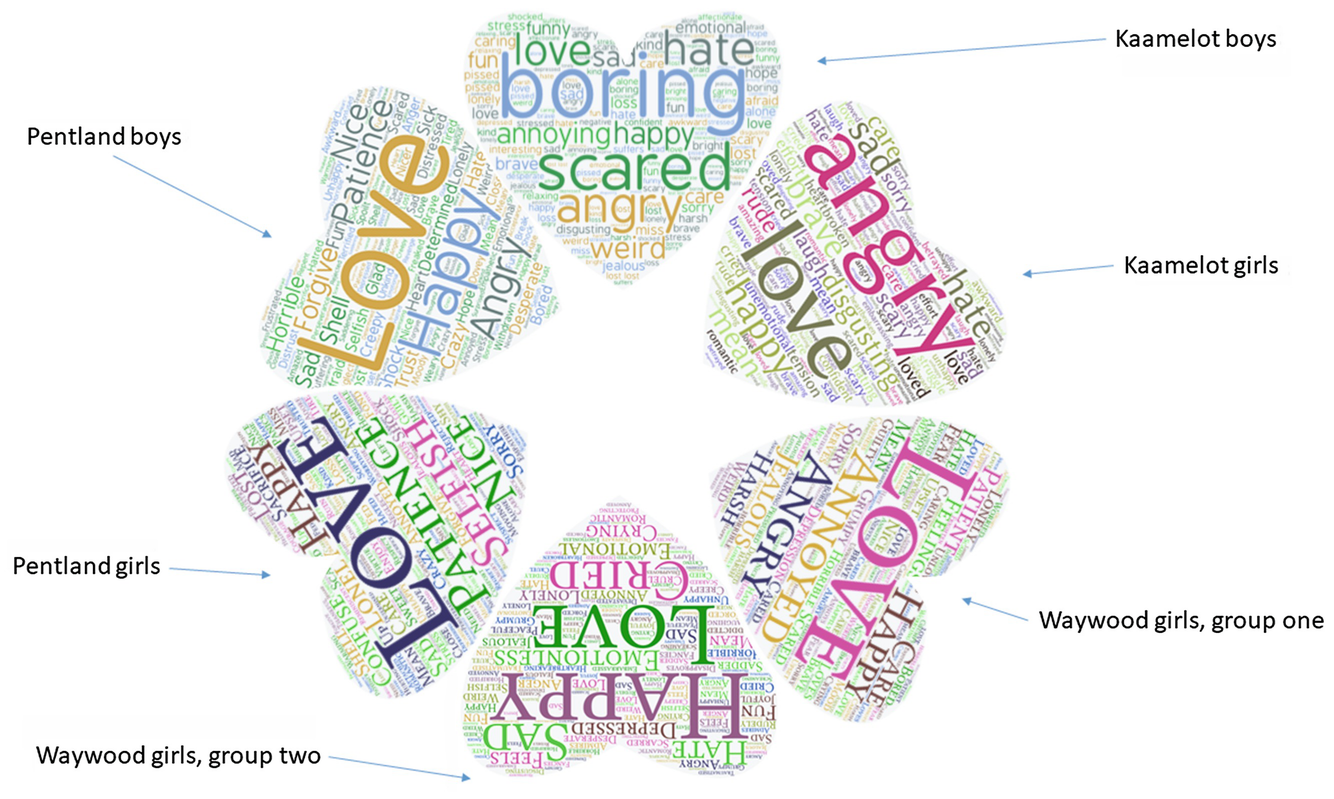

These examples begin to illustrate the number of different relationships and interactions which involve emotional labour in young people’s lives. They experience, like us all, a complex interweaving of emotions, behaviours, morals and values in relation to others. Young people are aware of the complexity of emotional labour because it is necessary in interactions with others. I have mainly cited female students talking about their feelings. This is an incorrect representation of what occurred in the groups. Conversations containing emotion were evenly distributed across each school and between males and females (as Illustration 3.1 shows). This point is further reinforced when I compare what words each gender used within the other two schools. Firstly, at Kaamelot the emotion most mentioned by both girls and boys was anger. Secondly, at Waywood the girls empathised with a character’s actions, or felt sorry for the way certain characters were treated; Millie said, ‘I feel quite sorry for the father cause he spent ages worrying about his kids and trying his hardest to look after them’. In contrast the boys felt happy about the outcomes of the stories: Mark said that he was ‘glad for the lad’ when the ploughboy succeeded in winning the princess in Rooted Lover , and he also said, while discussing Frog King, ‘There’s a build-up, there’s a problem, she doesn’t want to live with the frog, there’s a solution, he turns into a prince, nice happy ending’.

There was a slight difference between the boys at different schools: one group at Kaamelot felt bored and related to anger, being sad or lonely, which could be perceived as being more pessimistic; while the Waywood boys mentioned happiness and empathy, thus more hopeful emotions, as well as fear, jealousy and desperation. These findings correspond with Shamir and Travis (2002) who challenged that middle-class males felt alienated from their emotions via an analysis of twentieth-century US literature. Studies like this challenge psychiatry which suggests that ‘girls express more happiness, sadness, anxiety’ and ‘embarrassment’, while ‘boys express more anger and the externalizing of emotions, such as contempt’ (Panjwani et al. 2016, p. 117).

Emotions linked to fairy tales

Group Conflict

Emotional management is not limited to a person’s ability to express anger, Hochschild (2012, p. 21) argues that it also ‘affects the degree to which we listen to feeling and sometimes our capacity to feel’. Emotional management is enacted an individual’s personal life, such as how people act in groups; including what is acceptable to share and why, what is appropriate to feel and for how long, and where to express different feelings as determined by social norms. Considering situations of conflict, literature across many fields (psychology, developmental biology, evolutionary psychology, education, and sociology) suggests men feel more able than women to express themselves verbally and physically with aggressive and disruptive behaviour (Connell 2014, p. 47). Psychologist Sandra Thomas, a leading researcher on women’s anger, agrees that males and females have learnt to control their emotions differently: ‘Men have been encouraged to be more overt with their anger. If [boys] have a conflict on the playground, they act it out with their fists. Girls have been encouraged to keep their anger down’ (Dittmann 2003, p. 52). Developmental psychology, on the other hand, states that this is due to psychological differences during adolescence, such as a younger brain maturation rate in girls, and testosterone which causes aggression in boys. Feminist literature advocates that expressions of emotion like anger by women are indicative of ‘thwarted agency’, rather than gendered or irrational. In such ways anger is perceived as a positive transformation demonstrating independence rather than a destructive or an irrational trait (Pratt and Rosner 2012, p. 5). However, the largest risk factor related to a young person’s behaviour—that schools with a high incidence of behavioural problems need to be aware of—appears to be social through the encouragement of gendered behaviours by parents and wider society which cause inhibitory control or lack of control (Loeber et al. 2013, p. 160). Phrases like ‘boys will be boys’ contrasted against ‘sugar and spice and all things nice’, for girls, spring to mind in a British context.

Emotional labour is socially learnt, to use a metaphor each student in a classroom could be given the same ingredients for a cake but the outcome will be different depending on one’s previous experiences and skill. This is one reason people often have to ‘accept uneven exchanges’ (Hochschild 2012, p. 85) because people’s experience, expectations and patience levels differ. One could expect that children experience a wider range of uneven exchanges than adults, because of the way social structures and practices are informed by adult decisions. There are different constrains on young people’s emotional expression and behaviour compared to adults due to the limited extent young people are enabled to question and challenge emotional exchanges in an adult world. An illustration of the unevenness of exchanges, and a clear example of ‘gift exchange’, was when Mark protested that he had been ‘slapped’ (as illustrated in Chap. 3). As I previously described that example at length, here I will instead introduce the idea of emotions as a bridge between moral standards and behaviour.

my brother asked me to drive his car […] He wanted me to have the experience, know what it’s like […] my mum and dad never said don’t. They said, ‘Just think carefully if you’re going to do it’ […] I was scared . I didn’t know how to drive. So I didn’t […] If I did it was just going to go wrong

In the above example Jamal recounted his story in a disjointed fashion, I reordered his narrative to make it more logical to follow. Here the link between feelings (‘scared’) and Jamal’s behaviour (choosing whether to drive or not) is apparent. Jamal even used the word ‘wrong’ indicating that moral standards informed his actions.

Through discussing storytelling students engaged with their moral emotions. Critical engagement with fairy tales allowed them to learn from one another on an emotional level as well as a behavioural one. However, it is worth considering that an individual’s engagement could potentially respond in a variety of ways to fairy tales. An individual can reject or ignore fairy tales as a source of moral standards, and the storytelling space as a means of learning through connecting to others. Observing how young people interpreted character motivations in the storytelling space, and shared personal stories, allowed me to connect emotions and behaviour to fairy tales but does not prove this always occurs—just within the context of the storytelling space that I created. And yet, the students’ detailed interpretations arising from the storytelling space continue to challenge the psychoanalytic analysis of fairy tales (as summarised in Chap. 3) by demonstrating a varied interpretation of storytelling and the multiple ways in which storytelling can be connected to our emotional and behavioural lives.

Different Locations and Circumstances

- Holly

Our parents?

- Olive

Parents

- Holly

And the environment

- Belle

Our family

- Holly

People around you

- Olive

I think it’s not learned, it’s already there

- Holly

Yeah, but she was, born all happy and everything, or crying, and they tried to teach her that it was bad to do that

- Olive

Yeah, but she already had emotions

Belle’s and Olive’s first answers were ‘family’ and ‘parents’, respectively; Holly listed a range of different influences on emotion: parents, environment and people; Olive suggested emotions were innate not learned; and Holly explained that, yes, the princess in Toy Princess (De Morgan 1987 ) came into the world with feelings, but was then taught about what was appropriate. So the students perceived that emotional management was learned from different influences in their surroundings, with a key aspect of learning involving interactions with other people, especially family members. That all these thoughts were triggered by a storytelling space shows how impressive the students’ grasp of emotion was, and how crucial emotion is for daily interaction .

In this story the princess resembles a steel ball bouncing around a pin ball machine, between one kingdom where emotion is dissuaded and another where it is embraced. Foucault (1998, p. 63) argues that social processes, how people interact, and structures, such as institutions or class structure, reproduce uneven power distributions which individuals have no power over. He proposes that power is everywhere, outwith people’s processes of agency, or collective social structures. In other words (using my own metaphor), the flippers and bumpers of the pinball machine control the ball’s movements. The ball (representing the individual) does not have control over its own movements although sometimes it has the illusion of control.A princess was born in a kingdom where it was perceived as rude to express emotion, or to say anything but ‘Yes’, ‘Certainly’, and ‘Just so’. The princess was different from everyone else because she felt and expressed her emotions, and was reprimanded each time she laughed or cried. As a result she became ill. Her fairy godmother took the princess away to a kingdom where everyone was free to express their emotions. In the meantime, the fairy godmother replaced the princess (in secret) with a toy princess who only said, ‘Yes’, ‘Certainly’, and ‘Just so’. The kingdom were delighted with their new princess, and the actual princess grew strong and healthy. After many years the king became sick and the fairy godmother informed him of what she had done because he was talking about handing the kingdom over to the toy princess. The godmother gave the kingdom the option of keeping the toy princess or having their real princess returned. The kingdom chose the toy princess, and the real princess remained happily where she was in a land where she was free to express herself.

I find Foucault ’s theory rather depressing. Bourdieu (1984, p. 170), alternatively argues that individuals are ordered and constrained by constantly changing perceptions of the social and structural practices around them, and would therefore adapt. I think this is a more realistic perspective because humans have adapted, and shaped, their environment for thousands of years. Or perhaps this perspective feels right to me because I believe in the power of words, for some people; words provide hope to those that yearn to create the possibility of change towards better working or living conditions. And where is the place for young people to learn and question what they can change, and to do so with hope, if not in school?

- Emma

You guys were talking about feeling happy when everyone else was feeling sad. What do you then do?

- Holly

Stop, and you go, oh okay

- Olive

I would probably go to my room, if I’m surrounded by people I would try and get away from them

- Ava

If you were happy then I’d try and make everyone else happy, I wouldn’t let them all be sad

- Holly

Yeah but if you try to do that everyone else is, ‘No, this isn’t the right time’

- Olive

Yeah, if it’s a very serious situation and you’re, ‘Everybody be happy!’ That’s what happened in the, Christmas party we had in year 7. Me and Louise were there like, [raises voice excitedly] ‘Everybody!’

- Holly

I wasn’t in that day

- Olive

And everyone else was like, [lowers tone] ‘I don’t really care.’ Everyone was at their tables, like that [acts sad] eating their crisps [mimes eating crisps sadly]. And me and Louise were, [raises voice] ‘Whoo hooo party!’

The group above expressed three different behavioural strategies related to the following emotions: happiness, sadness and excitement. Holly said she would stop if her emotions were different to those around her, while Olive’s words, ‘try and get away’, suggested that she would leave to protect her own emotional state (happiness) over joining others in their sadness. On the other hand Ava said she would try to ‘make everyone else happy’ which was typical of her usual contributions to the group—always offering jokes and funny comments.

Holly and Olive disagreed that Ava’s strategy would always be appropriate. In a ‘serious situation’, despite Olive describing a school party as an example, Holly and Olive understood that certain circumstances required conforming to existing social power dynamics, how people interact, in order to respect others’ feelings. The girls’ brief conversation covered a number of Hochschild ’s (2012) ideas associated with social interactions: what was acceptable to share and why, what was appropriate to feel, and where different feelings were expressed as determined by the social situation. The management of emotional labour, as in the example above, is influenced by a diverse range of factors in school, social situations and at home.

Toy Princess was definitely a tale of emotions, the students discussed in relation to this story how emotional management could be learned from different influences in their surroundings. Interactions with other people, especially family members were important to these young people. This social influence from parents and family to young people suggests a top-down power dynamic which fits with ideas of socialisation (despite problems with the term mentioned in Chap. 2). One of the challenges to socialisation is the lack of agency given to young people. Young people are born into structures not of their own choosing (Marx 2006). Marx indicated that people had agency but it was constrained by the choices given to them, and must learn to negotiate the emotional and behavioural dimensions of social situations. Recollect the students mentioned that emotions were learned from parents, the environment and other people. In that example, Holly explained, yes, the princess in Toy Princess was born with feelings, but was then taught about what was appropriate.

Bourdieu (1984, p. 170) attempts to establish a link between social structures and social practice in his concept of habitus: ‘A structuring structure, which organises practices and the perception of practices’. Bourdieu suggests that self-identity is formed at the unfixed boundaries between social interactions and social structures. To make this clearer, let me use cohabiting as an example. Individuals absorb the patterns of social structures, those structures might inform a couple’s actions, whether consciously or unconsciously, about how to divide the housework, evenly or with one partner doing the majority. Bourdieu would say that the outcome of who does what in the household would be determined by how the majority divide the chores (forming a structural “norm”) which is then negotiated depending on the couple’s relationship with one another. Division of labour in the home, household objects, modes of consumption and parent-child relations are all examples of habitus (Bourdieu 1990; Nash 1999).

Heidi and Mary discussed dealing with their emotions in different ways in the family living room. This is an example of family power dynamics linked to habitus within a physical space. Heidi, Felicity, Mary and Paris talked about how they dealt with anger in family situations: ‘Me and mum do have our moments arguing,’ said Heidi, ‘I don’t argue with her [in the living room], I just let her argue at me and I stares and then I get it all out in my room’. Heidi mentioned expressing herself differently in two spaces in the home: downstairs in the family living room she controlled her emotions, while upstairs in her bedroom she let ‘it all out’. While being aware of controlling herself in front of her mother —‘I just let her rant at me’—Heidi felt the need to physically move and shout in her room. This physical release suggested that Heidi was physically and emotionally controlling herself downstairs. When Felicity asked Heidi, ‘What do you do to take it out? Do you punch the wall or something?’ Heidi said that she usually jumped on her bed, turned the music up, or screamed into her pillow. Heidi and Mary also discussed punching walls, which they had done before. Such actions might also be considered a way of resisting authority. Figures of authority might not be able to see Heidi’s actions; the music might or might not have masked her screaming and jumping; and as loud music would be audible in most modern houses, Heidi’s family allowed her to turn up her music (at least for a little while). How long she could turn up the music for was not clear. To Heidi, however, there was a clear division between what behaviour she communicated in different parts of the home and as a consequence we can observe emotional labour in action—involving what feeling was expressed where. Heidi might have learned what emotional labour was appropriate through social relationships within the family, such as acceptable social responses to parental figures in the home.

My mum says that we argue quite a bit because I was like her when she was young and we both put up a fight, but obviously she always wins [laughs] or she threatens stuff to me. I don’t know, if I’m going to go out at the weekend she’ll say, you can’t go, or take my pocket money off me or something.

Mary also stated about arguing with her mum, ‘I’ll have a go and then she’ll have a go at me.’ Mary’s experience differed from Heidi’s because Mary was able to have a dialogue with her mother. Mary’s experience of family and habitus differed from Heidi’s. Heidi did not mention that she was able to talk to her mother, except, ‘if my mum’s just yelling at me my dad comes along to stick up for me’. Heidi’s father accordingly became a mediating or protective figure in the household.

Paris responded to her mother in a similar way to Mary. ‘I can’t ignore it,’ she responded, ‘I’m just, “Argh, shut up!”’ Paris did not mention any resolution or dialogue with either of her parents, or in what parts of the home she expressed her anger. In response to what Heidi shared with the group about not replying to her mother, Paris reflected, ‘It would probably be better for me to do what you do but I can’t help myself.’ By saying this, Paris seemed to be aware that she might not have been able to copy Heidi’s emotional and behavioural strategy ‘stand there and listen’; however, Paris was acknowledging that an alternative emotional and behavioural strategy existed. Embodied expression, or transformation, of emotion appeared to be more significantly related to the physical space for Heidi rather than for Paris or Mary. The way in which Heidi’s and the other girls’ emotional expression differed in the home was consistent with Bourdieu ’s theory of the adaptability of habitus in relation to individuals’ situations and experiences.

[…] whenever my mum tells me off I just stay there and not answer back but when it’s other people who are my age or something I do have to fight back […] Me and my cousin argue all the time. It’s almost like she tries to give me a life lesson on what I should and shouldn’t do, like she did, and at the end of the day, I said, my life’s different to yours. I’ll try things that I want to try

The students’ emotional expressions were constrained by the different spaces they inhabited, such as the school and the research space. Perhaps Heidi acted differently around people her own age because the rules and entitlements of the social situation were different. I asked Heidi, who had been talking about arguing with her cousin a moment before, ‘Have you ever said anything to someone that you didn’t mean to say and it upset them?’ Mary, not Heidi, responded, ‘I’ve upset them but I’ve meant to say it [laughs]. Cause they’ve really got on my nerves and I don’t like them. It makes me sound really horrible but I’m not, I’m not a horrible person’. I added, ‘If it was someone who was close to you what would you do?’ Heidi said, ‘If I yelled at someone who was close to me I think I’d probably be really annoyed with myself’. Again, Mary differed. She felt that she did not owe anything to someone who annoyed her. Heidi reflected she would feel bad if she hurt someone she was close to. She felt that she owed her mother, possibly understanding that her mother shouted because she cared, whereas her cousin’s advice, although potentially being given for the same reasons, she perceived as interference because they were less close. Heidi protested in her room when her mother was involved, but in person against her cousin.

Examples of social exchange with parents, cousins, friends and teachers, had different levels of potential consequences. Different consequences would occur if Mary shouted at her mother or a teacher compared to shouting at her friend. For instance, Mary stated that she would lose privileges like the freedom to go out, or pocket money, if she argued with her mum. Arguing with a sibling had a lower associated social and disciplinary cost. Paris, for example, said, ‘Me and my sister have a fight and then five minutes later we’re like, yeah, do you want to do my hair?’. Such different embodied responses, demonstrated by the girls in relation to parental or authority figures, were indicative of Hochschild ’s processes of emotional labour during social exchange. Hochschild proposed that emotional management was central to social interaction because social interactions required negotiating boundaries between one’s own feelings and others’ (Hochschild 2012, p. 56).

To be honest, all the people that I’ve felt jealous for I’ve just tried to keep my chin up, cause at the end of the day I’ve always thought that people who try and make you jealous karma will come back to them […] I just think that everybody has a right to be themselves.

Heidi provided herself with an internal narrative, which allowed her to dismiss her jealousy by framing others’ attempts to make her jealous as controlling. Heidi means ‘justice’ rather than karma which refers to previous lives. By transforming her emotional state, Heidi refused to act like others, based on her experience. Inaction also arose when students chose not to answer a focus group question, for instance, responding to question five, ‘How did the story make you feel?’, Millie said, ‘I can relate to the dad because I can empathise with the dad.’ Mark stated, ‘That doesn’t relate to your life.’ Millie responded, ‘Oh, bit personal’ and chose not to answer the question. By observing emotion in the storytelling space using Hochschild ’s concept of emotional labour I reflected on current educational practices.

What Storytelling May Reveal About Current Education Practices

Emotion has been considered within education studies, such as therapeutic pedagogy which outlines teachers’ and students’ emotional practices and norms. There has been much emphasis on how contemporary education can build self-esteem or resilience, also known as grit (Duckworth et al. 2007). These approaches require caution because practices that focus on empowering students carries a danger of forming diminishing views of people’s own capacities, the reserves that they already have in terms of inner resilience and autonomy (Ecclestone 2004; Zembylas 2007). Until my project, research about Hochschild ’s concept of emotional labour has been adult-focused and work-related, rather than associated with the experiences of young people in school contexts (Yin et al. 2013, p. 143). Using storytelling methods suggests that the management of emotions through emotional labour plays an important social role during group discussion. In schools, storytelling has value as a technique as it is an unobtrusive method to encourage the discussion of emotions while providing an enjoyable experience to participants. It is important not to remove the joy and spontaneity out of the lived experience of story. Storytelling could be used more in schools, although care needs to be taken to avoid turning the storytelling experience into another monitored assessment space.

Emotional labour and its associated actions are not necessarily a linear or straightforward process; there is complexity and ambiguity when interpreting the interaction of inner feelings, using external expression and action within a social situation. The stories of young people surrounding emotion, shared in this chapter show that young people learn how to interact with others through the pressures placed on them, via stories like fairy tales, to follow the morals and values of the society they live in. The link between emotional labour and classroom practices requires further research, as this was one idea which arose from taking storytelling into schools because I did not know about Hochschild’s concept beforehand. In current educational practices emotions are used in English classrooms to interpret text. Department of Education (Department for Education 2014) guidelines state that young people must ‘have a chance to develop culturally, emotionally, intellectually, socially and spiritually’ which suggests education is about more than the memorisation of information as it is also about these things. I could rephrase this in another way, Department of Education guidelines reflect that emotion is one of the required skills to participate fully ‘as a member of society’. Which leads me to ask, pilfering from lines from Goldilocks, are we too cold, too hot or just right in the classroom in supporting young people’s emotional learning?

[U]nderstanding a word, phrase or sentence in context; exploring aspects of plot, characterisation, events and settings; distinguishing between what is stated explicitly and what is implied; explaining motivation, sequence of events, and the relationship between actions or events (Department for Education 2013, pp. 4–5).

Parallels can be drawn here through the work of Hochschild , between ‘how society uses feeling’ (2012, p. 17) and how the students were educated to use feeling through educational policies such as the National Curriculum. There are significant similarities between these educational guidelines and the way in which students interpreted storytelling. The students understood a character’s emotional and behavioural ‘motivation’, and linked this to ‘actions or events’. For instance, Millie perceived the husband rejected his wife because of his emotional state. My research indicated that, at least for the young people in my study, the education system has been effective in providing them with the tools young people need to link and interpret a wide range of texts. It follows, that the same way of interpreting behaviour and emotions in school texts might arise in other situations in the students’ lives.

I found that education provides a way of intellectualising or instrumentalising emotion, which I will now explain. The students understood the actions of characters via their emotions, including their internal emotional states. For example, the all-female school students were set an essay on Romeo and Juliet for English. Heidi said, ‘We had to pick different quotations’ from the balcony scene on ‘fear’ and ‘love’. Mary added, ‘We had to look at feelings’ then ‘describe it from the audience perspective’. Educational policy places Shakespeare on the curriculum as a national literature of importance, and Shakespeare is taught around the world though the same ideas can apply to other novels, plays and poetry, to name a few forms of story.

Above I cited Department for Education guidelines (2013, p. 4) which state that GCSE English literature should deepen students’ understanding of key texts. This form of interpretation is an intellectualising of emotion because the focus of an English essay on emotion in Shakespeare’s play indicates the way in which the students were educated to understand key texts by interpreting the motivations of characters via their emotions. Emotion is important to interpretation.

The National Curriculum combined with behavioural and disciplinary guidelines place young people in a subordinate position, where they are expected to conform to a set of behavioural rules determined by figures of authority which promote ‘good behaviour’ and ‘self-discipline’ (Department for Education 2016, p. 4). Educational practices are designed to promote students’ education and welfare and the control and subordination of young people’s behaviour towards instrumental ends. To clarify, I do not want to imply that behavioural policy in schools is like a dictatorship, or even that young people’s conformity to the rules has positive or negative outcomes, rather that fitting in to some extent is necessary for social cooperation, but does not mean policies and practices should not be brought into question, particularly when considering who is being effected, and towards what purposes.

Young people are required to interpret emotions and behaviour in certain ways to obtain high grades, yet the ways this happens are less discernible than the way in which employers train customer service staff to perform emotional labour. Whether emotional training occurs through interaction with text in educational settings is less discernible because there are multiple factors to consider some of which include text selection, how gender and ethnicity and class is represented in that text, who has or lacks a voice, and what essay topics are set by the teacher. Two important questions for further research, or to consider in terms of classroom practices, are ‘Do processes of interpreting character’s actions through emotion, in a standardised way in English classrooms, encourage the “normalisation” of emotional practices?’ and ‘Does this perpetuate existing inequalities in the classroom between people with different backgrounds and different emotional experiences?’

This chapter is essentially an argument that acknowledging different emotional backgrounds is important to understand and accommodate the needs of students. Why?, (1) emotion is crucial to interpreting text, (2) understanding one’s own emotions and interpreting the emotions of other is important to interact with others, and (3) current education practices involving emotion may be sustaining inequality in terms of academic success, if alternative and unexpected answers are not accepted as part of the process. Storytelling is one way to provide a space in schools for young people to explore their connections to story through emotion, as well as working on co-operation, emotional and social skills. It is a space where they can share ideas and learn from each other, and learn their opinions and emotions matter. Storytelling, as a space for emotional expression, demonstrates that traditional, oral storytelling offers an alternative approach for teachers. This is why I propose storytelling spaces in schools are vitally important and should be offered across the UK. This can work if such spaces are created and sustained by young people, parents, teachers, storytelling professionals, funders and policy makers.