139 Adjectives in French tend to follow the noun (e.g. un livre difficile ‘a difficult book’). However, some adjectives must and others may precede the noun (e.g. un petit garçon ‘a little boy’), and there is indeed an increasing tendency on the part of journalists and others to put in front of the noun adjectives that would more usually be found after it (e.g. une importante décision for une décision importante ‘an important decision’) (see 148). A safe principle to follow is that the adjective should be placed after the noun unless there is some reason for doing otherwise. The main rules and tendencies relating to contexts in which the adjective must or may come before the noun are set out in sections 140–151.

140 The following adjectives usually precede the noun:

| beau, beautiful, fine | mauvais, bad |

| bon, good | meilleur, better, best |

| bref, brief | moindre, less, least |

| grand, big, great | petit, little, small |

| gros, big | sot, foolish |

| haut, high | vaste, immense |

| jeune, young | vieux, old |

| joli, pretty | vilain, ugly, nasty |

This remains true even when these adjectives are preceded by one or other of the short adverbs assez ‘rather, quite’, aussi ‘as’, bien ‘very’, fort ‘very’, moins ‘less’, plus ‘more’, si ‘so’, très ‘very’, e.g. un assez bon rapport ‘quite a good report’, une plus jolie robe ‘a prettier dress’, un très grand plaisir ‘a very great pleasure’.

Note, however: (i) d’un ton bref ‘curtly’, une voyelle brève ‘a short vowel’; (ii) la marée haute ‘high tide’, à voix haute (or à haute voix) ‘aloud’; (iii) un sourire mauvais ‘a nasty smile’ (and also with various other nouns – consult a good dictionary).

If modified by a longer adverb or adverbial phrase these adjectives normally follow the noun, e.g. une femme exception-nellement jolie ‘an exceptionally pretty woman’, un homme encore jeune ‘a man still young’, des différences tout à fait petites ‘quite slight differences’.

141 Court ‘short’ and long ‘long’ tend to precede the noun (e.g. un court intervalle ‘a short interval’, une courte lettre ‘a short letter’, un long voyage ‘a long journey’, une longue liste ‘a long list’) except when (as frequently happens) there is a contrast or an implied contrast, i.e. ‘short as opposed to long’ or vice versa, e.g. une robe courte, une robe longue ‘a short/long dress’, des cheveux courts/longs ‘short/long hair’, une voyelle courte/longue ‘a short/long vowel’.

142 Dernier ‘last’ (see also 183) and prochain ‘next’ meaning ‘last or next as from now’ follow words designating specific moments or periods of time such as semaine ‘week’, mois ‘month’, an, année ‘year’, siècle ‘century’, names of the days of the week or of the seasons, and (in the case of dernier only) nuit ‘night’, e.g. la semaine dernière ‘last week’, le mois prochain ‘next month’, l’an dernier/prochain, l’année dernière/prochaine ‘last/next year’, le siècle dernier ‘last century’, lundi prochain ‘next Monday’, l’été dernier ‘last summer’, la nuit dernière ‘last night’. Otherwise they precede the noun, e.g. la dernière/prochaine fois ‘last time, next time’, la dernière semaine des vacances ‘the last week of the holidays’, la prochaine réunion ‘the next meeting’, le dernier mardi de juin ‘the last Tuesday in June’, le prochain village ‘the next village’.

143 Nouveau ‘new’ follows the noun when it means ‘newly created’ or ‘having just appeared for the first time’, e.g. du vin nouveau ‘new wine’, des pommes (de terre) nouvelles ‘new potatoes’, un mot nouveau ‘a new (i.e. newly coined) word’, une mode nouvelle ‘a new fashion’; otherwise – and most frequently – it precedes the noun, e.g. le nouveau gouvernement ‘the new government’, j’ai acheté une nouvelle voiture ‘I’ve bought a new (i.e. different) car’.

144 Faux ‘false’ usually precedes the noun, e.g. un faux problème ‘a false problem’, une fausse alerte ‘a false alarm’, une fausse fenêtre ‘a false window’, un faux prophète ‘a false prophet’, de faux papiers ‘false papers’, but follows it in certain expressions such as des diamants faux ‘false diamonds’, des perles fausses ‘false pearls’, un raisonnement faux ‘false reasoning’, des idées fausses ‘false ideas’.

145 Seul before the noun means ‘single, sole, (one and) only’, e.g. c’est mon seul ami ‘he is my only friend’, la seule langue qu’il comprenne ‘the only language he understands’. After the noun it means ‘alone, on one’s own’, e.g. une femme seule ‘a woman on her own’. Note too the use of the adjective seul in contexts where English uses ‘only’ as an adverb, e.g. Seuls les parents peuvent comprendre ‘Only parents can understand’, Seule compte la décision de l’arbitre ‘Only the referee’s decision (the referee’s decision alone) counts’.

146 Some other adjectives have one meaning when they precede the noun and a different one when they follow the noun. In some cases the two meanings are very clearly distinguishable. In other cases, the distinction is less sharp but there is a tendency for the adjective to have a literal meaning or to be used objectively when it follows the noun and to have a more figurative meaning or to be used more subjectively when it precedes the noun. It is not possible to give a full list of all such adjectives, nor is a grammar the place to attempt to cover the full range of meanings of each adjective that is listed – a dictionary should be consulted. The following list includes only the more common of the adjectives in question and some of their more usual meanings (others whose usage should be looked up in a dictionary include chic, digne, fameux, franc, maudit, plaisant, sacré, véritable):

| Meaning before the noun | Meaning after the noun | |

| ancien | former, ex- | old, ancient |

| brave | nice, good, decent | brave |

| certain | certain, some | sure, certain |

| cher | dear, beloved | dear, expensive |

| différent | (plural) various | (sing. and plural) different |

| divers | (plural) various, several | (sing. and plural) differing |

| méchant | poor, second-rate, nasty | malicious |

| même (see 300) | same | very, actual |

| pauvre | poor (pitiable, of poor quality) | poor, needy |

| propre | own | clean, suitable |

| sale | nasty | dirty |

| simple | mere | simple, single |

| triste | wretched, sad | sad, sorrowful |

| vrai | real, genuine | true |

Examples:

| un ancien cinéma a former cinema |

la ville ancienne the old city |

| au bout d’un certain temps after a certain time |

une preuve certaine definite proof |

| certains Français certain French people |

des indications certaines sure indications |

| différentes personnes various people |

des avis différents different opinions |

| un méchant petit livre a wretched little book |

des propos méchants malicious remarks |

| les mêmes paroles the same words |

ses paroles mêmes his very (actual) words |

| pauvre jeune homme! poor young man! |

un jeune homme pauvre a penniless young man |

| ma propre maison my own house |

une maison propre a clean house |

| le mot propre the right word |

|

| un sale tour a dirty trick |

des mains sales dirty hands |

| une simple formalité a mere formality |

une explication simple a simple explanation |

| un aller simple a single ticket |

147 A preceding adjective refers only to the noun that immediately follows; where there is, in English, an implication that an adjective refers to more than one following noun, it must be repeated in French, e.g.:

un beau printemps et un bel été

a fine spring and summer

les mêmes mots et les mêmes expressions

the same words and expressions

(On following adjectives qualifying more than one noun, see 127, iii.)

148 The following normally go after the noun:

(a) Adjectives denoting nationality or derived from proper names, or relating to political, philosophical, religious, artistic movements, etc., e.g.:

la langue française

the French language

une actrice américaine

an American actress

les provinces danubiennes

the Danubian provinces

la politique gaulliste

Gaullist policy (i.e. that of General de Gaulle)

un personnage cornélien

one of Corneille’s characters

les théories marxistes

Marxist theories

la religion chrétienne

the Christian religion

la peinture surréaliste

surrealist painting

(b) Adjectives denoting colour, shape or physical qualities (other than those, many of which relate to size, listed in 140), e.g.:

| une robe blanche | a white dress |

| une fenêtre ronde | a round window |

| un toit plat | a flat roof |

| une rue étroite | a narrow street |

| un oreiller mou | a soft pillow |

| une voix aiguë | a shrill voice |

| de l’or pur | pure gold |

| un goût amer | a bitter taste |

Some of these, however, may occur in front of the noun, particularly when they are used figuratively, e.g. le noir désespoir ‘black despair’, une étroite obligation ‘a strict obligation’, une molle résistance ‘feeble resistance’, la pure vérité ‘the plain truth’. But they by no means invariably precede the noun even when used figuratively (e.g. l’humour noir ‘sick humour’, une amitié étroite ‘a close friendship’).

(c) Present and past participles used as adjectives, e.g.:

| un livre amusant | an amusing book |

| du verre cassé | broken glass |

| la semaine passée | last week |

Note, however, that prétendu ‘so-called, alleged’ and the invariable adjective soi-disant ‘so-called’ (see 136, iii) precede the noun, e.g. mon prétendu ami ‘my so-called friend’, la prétendue injustice ‘the alleged injustice’, la soi-disant actrice ‘the so-called actress’.

149 In general, polysyllabic adjectives tend to follow rather than precede the noun. However, there seems to be an increasing tendency for such adjectives to be placed before the noun when they express a value judgement or, even more so, a subjective or emotional reaction. Such adjectives include adorable, affreux ‘dreadful’, délicieux ‘delightful’, effrayant ‘frightful’, effroyable ‘appalling’, énorme ‘enormous’, épouvantable ‘terrible’, excellent, extraordinaire ‘extraordinary’, important, inoubliable ‘unforgettable’, magnifique ‘magnificent’, superbe, terrible, and many others, e.g. un adorable petit village ‘a delightful little village’, une épouvantable catastrophe ‘a terrible catastrophe’, un magnifique coucher de soleil ‘a magnificent sunset’.

150 It is perfectly possible for a noun to take adjectives both before and after it, as in une belle robe bleue ‘a beautiful blue dress’, un jeune homme habile ‘a capable young man’.

151 A noun may be preceded and/or followed by two or more adjectives; except in the type of construction dealt with in 152 below, two adjectives preceding or following the noun are linked by et ‘and’ (or by ou ‘or’ if two following adjectives are presented as alternatives), e.g.:

une belle et vieille cathédrale

a beautiful old cathedral

un étudiant intelligent et travailleur

an intelligent, hard-working student

des journaux anglais ou français

English or French newspapers

Where more than two adjectives are associated in a similar way with the same noun, the last two are linked by et or ou, e.g. des étudiants intelligents, travailleurs et agréables ‘intelligent, hardworking, pleasant students’.

152 In the examples given in 151, each adjective modifies the noun so to speak independently and equally. Sometimes, however, one adjective modifies not just the noun but the group adjective + noun or noun + adjective, in which case there is no linking et, e.g. in un gentil petit garçon ‘a nice little boy’ the adjective gentil modifies the whole phrase petit garçon, and in la poésie française contemporaine ‘contemporary French poetry’ (in which the reference is not to poetry which happens to be both French and contemporary but to French poetry of the present time) contemporaine modifies the whole of the phrase la poésie française.

153 (i) When an adverb precedes the verb and governs a predicative adjective, English places the adjective immediately after the adverb it is linked to by grammar and sense, while French keeps the adjective in the usual position for predicative adjectives, viz. after the verb. This affects adjectives used with:

(a) the adverbs of comparison plus ‘more’ and moins ‘less’, e.g.:

Plus le problème devenait complexe, moins il paraissait inquiet

The more complex the problem got, the less worried he seemed

(b) with adverbs meaning ‘how’, viz. combien, comme and que, e.g.:

Je comprends combien vous devez être inquiet

I understand how worried you must be

Comme il est facile de se tromper!

How easy it is to be wrong!

Qu’il est bête!

How stupid he is!

(ii) French uses a parallel construction with tant, tellement ‘so’ where English tends to put the group ‘so’ + adjective after the verb, e.g.:

On aurait cru l’été, tant le soleil était beau (Loti)

You would have thought it was summer, the sun was so beautiful

(This could also be translated ‘so beautiful was the sun’ or, more idiomatically, ‘The sun was so beautiful that you would have thought it was summer’.)

Il n’y arrivera jamais, tellement il est nerveux

He’ll never manage to do it, he’s so nervous (He’s so nervous he’ll never manage)

154 In English, adjectives precede the adverb ‘enough’ but in French they follow the adverbs assez ‘enough’, suffisamment ‘enough, sufficiently’, e.g.:

Elle n’est pas assez intelligente pour comprendre

She isn’t intelligent enough to understand

Il est suffisamment grand pour voyager seul

He’s old enough to travel on his own

155 As adjectives and adverbs have the same degrees of comparison and as the constructions involved are the same in each case we shall discuss them together.

156 There are four degrees of comparison, but one, the comparative of equality or inequality, sometimes known as the equative, has no special forms in either English or French (see 157). They are:

| (i) | the absolute – e.g. (in English) good, hard, difficult, easily | |

| (ii) | the equative – e.g. (not) as good as, (not) as easily as | |

| (iii) | the comparative, which can be subdivided into: | |

| (a) | the comparative of superiority, e.g. better, harder, more difficult, more easily | |

| (b) | the comparative of inferiority, e.g. less good, less easily | |

| (iv) | the superlative – e.g. the best, the hardest, the most difficult, (the) most easily. | |

The comparative of equality or inequality (the equative)

157 In affirmative sentences the comparative of equality (English ‘as … as …’) is expressed by aussi … que … , e.g.:

Il est aussi grand que vous

He is as big as you (are)

Elle est aussi intelligente que belle

She is as intelligent as she is beautiful

Il comprend aussi facilement que vous

He understands as easily as you (do)

Ils sont aussi charmants que vous le dites

They are as charming as you say

In negative sentences, aussi is usually replaced by si, e.g.:

Il n’est pas si grand que vous

He is not as big as you (are)

Ils ne sont pas si charmants que vous le dites

They are not as charming as you say

though aussi is possible (Il n’est pas aussi grand que vous).

On constructions of the type Il est aussi grand que vous ‘He is as big as you (are)’, Vous travaillez aussi énergiquement que nous ‘You work as energetically as we (do)’, i.e. where English has the option of using after a comparative a verb that repeats or stands for that of the previous clause, see 173.

158 As in English, the second half of the comparison may be omitted, e.g.:

Je n’ai jamais vu un si (or aussi) beau spectacle

I never saw so fine a sight

The comparative and superlative of superiority or inferiority

159 The comparative of superiority or of inferiority is formed (apart from the cases noted in 161) by means of the adverbs plus ‘more’ or moins ‘less’, e.g.:

| absolute | comparative of superiority |

comparative of inferiority |

| intelligent intelligent |

plus intelligent more intelligent |

moins intelligent less intelligent |

| facilement easily |

plus facilement more easily |

moins facilement less easily |

| souvent often |

plus souvent more often |

moins souvent less often |

The adjective agrees in the normal way, e.g. Elle est plus grande que moi ‘She is taller than me’, dans des circonstances moins heureuses ‘in less happy circumstances’.

160 (i) The superlative of adjectives of superiority or of inferiority is formed (apart from the cases noted in 161) by placing the definite article, in the appropriate gender and number, before the comparative, e.g.:

| absolute | superlative of superiority |

superlative of inferiority |

| intelligent | le plus intelligent | le moins intelligent |

| intelligent | the most intelligent | the least intelligent |

Adjectives that normally precede the noun (see 140) also do so in the superlative, e.g.:

| le plus jeune garçon | the youngest boy |

| la moins belle vue | the least beautiful view |

| les plus grandes difficultés | the greatest difficulties |

With adjectives that follow the noun, the superlative is constructed as follows:

| l’homme le plus intelligent | the most intelligent man |

| la femme la plus intelligente | the most intelligent woman |

| les hommes les moins intelligents | the least intelligent men |

| les femmes les moins intelligentes | the least intelligent women |

Note that, with either a preceding or a following adjective, a possessive determiner (see 223) may be substituted for the definite article according to the following models:

(a) with a preceding adjective:

| mon plus grand plaisir | my greatest pleasure |

| sa moins belle sœur | his least beautiful sister |

| nos plus vieux amis | our oldest friends |

(b) with a following adjective:

| son livre le plus célèbre | his most famous book |

| ma cousine la moins intelligente | my least intelligent cousin |

| nos montagnes les plus élevées | our highest mountains |

(ii) The superlative of adverbs is formed by placing le before the comparative, e.g.:

| le plus agréablement | the most pleasantly |

| le moins souvent | the least often |

Note that, since adverbs cannot agree (like adjectives) with nouns or pronouns, these forms are invariable, i.e. the article is always le, e.g.:

C’est elle qui travaille le plus intelligemment

She is the one who works the most intelligently

(For the superlative adverb modifying an adjective, see 170.)

161 The comparative and superlative of the adjectives bon ‘good’, mauvais ‘bad’, petit ‘small’ and of the corresponding adverbs have the following irregular forms (but see also 163 and 164):

| absolute | comparative | superlative |

| bon, good | meilleur, better | le meilleur, best |

| mauvais, bad | pire, worse | le pire, worst |

| petit, small | moindre, less(er) | le moindre, least |

| bien, well | mieux, better | le mieux, best |

| mal, badly | pis, worse | le pis, worst |

| peu, little | moins, less | le moins, least |

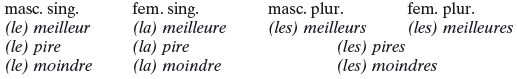

The adjectives agree in gender and number with their nouns as follows:

The adverbs are of course invariable.

Note that some, but not all, of these forms are subject to certain restrictions and that, for some of them, ‘regular’ comparatives and superlatives such as (le) plus mauvais occur – see 163–164.

162 The comparative and superlative of bon and bien are always (le) meilleur and (le) mieux respectively, e.g.:

Ce pain est meilleur que l’autre

This bread is better than the other

Leurs meilleurs amis

Their best friends

Il chante mieux que vous

He sings better than you (do)

C’est le matin que je travaille le mieux

It’s in the morning that I work (the) best

The rule applies even to expressions such as bon marché ‘cheap’ (meilleur marché ‘cheaper’, le meilleur marché ‘cheapest’) and de bonne heure ‘early’ (de meilleure heure ‘earlier’ – though a more usual rendering for ‘earlier’ is plus tôt).

163 The comparative and superlative of mauvais are either (le) pire or (le) plus mauvais. The two are often interchangeable, but in so far as there is any distinction it is (a) that (le) pire occurs more widely in literary than in spoken usage, and (b) that (le) pire in any case tends to be restricted to contexts in which it refers to abstract nouns, e.g.:

Votre attitude est pire que la sienne

Your attitude is worse than his

le pire danger

the worst danger

but:

Ce vin est plus mauvais que l’autre

This wine is worse than the other

le plus mauvais restaurant de la ville

the worst restaurant in town

(Note, however, that French often says moins bon ‘less good’ where English says ‘worse’, e.g. Cette route est moins bonne que l’autre ‘This road is worse than (or not as good as) the other’.)

The adverb (le) pis ‘worse, worst’ is even less used than pire and, for practical purposes, it can be assumed that the normal comparative and superlative of mal ‘badly’ are plus mal and le plus mal. Pis can never be used as an alternative to plus mal in, for example, a context such as Il chante plus mal que vous ‘He sings worse than you’. Apart from the one expression tant pis (pour vous, pour lui, etc.) ‘so much the worse (for you, for him, etc.)’, it is rarely heard in conversational usage and even in literary usage it is confined to a few expressions like aller de mal en pis ‘to go from bad to worse’, qui pis est ‘what is worse’, rien de pis ‘nothing worse’, le pis ‘the worst thing’, mettre les choses au pis ‘to put things at their worst, to assume the worst’, and even in some of these it can be replaced by pire, e.g. ce qui est pire ‘what is worse’, rien de pire, le pire, mettre les choses au pire. (Note too the use of moins bien ‘less well’ as a frequent alternative to plus mal.)

164 As the comparative and superlative of petit, the form (le) plus petit must always be used when reference is to physical size, e.g.:

Il est plus petit que je ne croyais

He is smaller than I thought

le plus petit verre

the smallest glass

The form moindre occasionally occurs as the equivalent of ‘less’, e.g. des choses de moindre importance ‘things of less importance’, but is more common as a superlative, particularly as the equivalent of English ‘least, slightest’, e.g.:

| son moindre défaut | his slightest failing |

| les moindres détails | the smallest details |

| sans la moindre difficulté | without the slightest difficulty |

| Je n’ai pas la moindre idée | I haven’t the slightest idea |

| la loi du moindre effort | the law of least effort |

On the other hand, the comparative and superlative of the adverb peu are invariably moins and le moins ‘less, (the) least’, e.g.:

moins difficile

less difficult

J’ai moins de temps que vous

I have less time than you

C’est lui que j’aime le moins

He is the one I like (the) least

Note that where English uses ‘the least’ with a noun, meaning ‘the least amount of’, French uses le moins de (with the optional addition, as in English, of the adjective possible), e.g.:

C’est comme ça qu’on le fait avec le moins de difficulté

That’s the way to do it with the least difficulty

Do not confuse this with constructions involving a negative or sans ‘without’, e.g.:

| De cette façon vous n’aurez pas la moindre difficulté | In this way you will not have the slightest difficulty |

| De cette façon vous le ferez sans la moindre difficulté | In this way you will do it without the slightest difficulty |

in which the meaning is not ‘the least amount of difficulty’ but ‘the smallest difficulty’.

165 The adverb beaucoup ‘much, many, a lot’ has as its comparative and superlative plus and le plus, e.g.:

J’ai plus de temps que vous

I have more time than you (have)

C’est le soir que je travaille le plus

It’s in the evening that I work most

166 ‘Than’ (except when followed by a numeral, see 167) is translated by que. In an affirmative sentence ne is often put before the following verb (see 563), e.g.:

Il est plus fort que son frère

He is stronger than his brother

Il travaille mieux que je (ne) croyais

He works better than I thought

167 Except in the type of sentence referred to in 168 below, ‘than’ followed by a numeral (including fractions) is translated by de instead of que, e.g.:

J’en ai plus de trente

I have more than thirty of them

Cela coûte plus de dix mille euros

That costs more than ten thousand euros

Il en a mangé plus de la moitié

He has eaten more than half of it

Il a vécu moins de dix ans

He lived less than ten years

168 In the type of sentence discussed in 167, ‘more than’ means ‘in excess of’ and ‘less than’ means ‘a quantity less than’. There is, however, a totally different construction in which ‘than’ is followed by a numeral and in which it is translated not by de but, as in most other contexts, by que, e.g.:

Un seul œuf d’autruche pèse plus que vingt œufs de poule

A single ostrich egg weighs more than twenty hen’s eggs

The reason is that this does not, of course, mean ‘more than twenty’ in the sense of ‘at least twenty-one’. What is being compared is the weight of an ostrich egg and the weight of hen’s eggs; vingt œufs de poule is in fact the subject of a clause whose verb is understood but which could have been expressed, in either French or English:

Un seul œuf d’autruche pèse plus que vingt œufs de poule ne pèsent

A single ostrich egg weighs more than twenty hen’s eggs weigh

The sentence in question is therefore an exact parallel with a sentence such as the following which does not involve a numeral:

Cet œuf pèse plus que celui-là

This egg weighs more than that one

169 When a comparative or superlative relates to two or more adjectives or adverbs, (le) plus or (le) moins is repeated with each, even if the corresponding adverb is not repeated in English e.g.:

Il est plus intelligent et plus travailleur que son frère

He is more intelligent and hard-working than his brother

Elle parle moins couramment et moins correctement que vous

She speaks less fluently and correctly than you

le problème le plus compliqué et le plus difficile

the most complicated and difficult problem

170 (i) When le plus ‘the most’, le moins ‘the least’, le mieux ‘the best’ followed by an adjective or a participle have the value of ‘to the highest (lowest, best) extent’, i.e. when the comparison is not between different persons or things but between different conditions relating to the same person(s) or thing(s), the article is invariable (i.e. always le), e.g.:

C’est en été qu’elle est le plus heureuse

She is happiest in summer (It is in summer that she is happiest)

(i.e. in summer ‘she’ is happier than the same ‘she’ in other conditions)

C’est quand ils sont fatigués qu’ils sont le moins tolérants

It’s when they are tired that they are (at their) least tolerant

C’est ici qu’elles seront le mieux placées pour voir

This is where they’ll be best placed (i.e. in the best position) to see

(ii) When other adverbs in the superlative (i.e. adverbs themselves qualified by le plus or le moins) qualify an adjective or participle, either construction is sometimes possible, with a slight (almost negligible) difference in meaning, e.g. les soldats les plus gravement blessés ‘the most seriously wounded soldiers’ interpreted as a parallel construction to les soldats les plus malades (i.e. the construction is les plus + gravement blessés), or les soldats le plus gravement blessés, interpreted as ‘the soldiers who are wounded to the most serious extent’ (i.e. le plus gravement + blessés). However, it seems that in practice, and regardless of logic, the former construction, with a definite article agreeing with the noun, is the usual one.

171 Note the following uses of de in comparative or superlative constructions:

(i) to express the ‘measure of difference’ (i.e. the extent to which the items compared differ), e.g.:

Il est plus grand que vous de trois centimètres

He is three centimetres taller than you

Ce dictionnaire est de beaucoup le plus cher

This dictionary is by far the most expensive

(this is not restricted to comparative and superlative constructions – cf. dépasser quelqu’un d’une tête ‘to be a head taller than someone’, gagner de trois longueurs ‘to win by three lengths’)

(ii) as the equivalent of English ‘in’ in such contexts as:

l’élève le plus paresseux de la classe

the laziest boy in the class

le meilleur restaurant de Paris

the best restaurant in Paris

172 Le plus and le moins are always superlatives in French, never comparatives. Consequently, plus and moins alone, with no article, are used in such contexts as the following where English uses the definite article ‘the’ with a comparative:

Plus il gagne, moins il est content

The more he earns, the less contented he is

Plus tôt vous arriverez, plus tôt vous pourrez partir

The earlier you arrive the earlier you’ll be able to get away

In literary usage, the second term of the comparison is sometimes introduced by et, e.g.:

Plus je vieillis, et moins je pleure (Sully Prudhomme)

The older I grow, the less I weep

173 After a comparative of equality (see the end of section 157), superiority or inferiority, French normally does not use a second verb that merely repeats or stands for (like ‘did’ in the third example below) the verb of the previous clause, e.g.:

Il est aussi grand que moi

He is as tall as I (am)

J’ai plus de temps que vous

I have more time than you (have)

Il a chanté mieux que son frère

He sang better than his brother (did)

Absolute superlative

174 (i) There is an important distinction to be made between the type of superlative adjective discussed in 160 (i.e. the type l’enfant le plus intelligent ‘the most intelligent child’) and a not dissimilar construction in which English uses not the definite article ‘the’ but the indefinite article (e.g. ‘a most intelligent child’) or, in the plural, no article (e.g. ‘those are most dangeous ideas’). The former, which characterizes a noun in relation to others of the same kind, is known as the ‘relative superlative’. The latter, which expresses the idea that the person or thing denoted by the noun is characterized by a high degree of the quality denoted by the adjective, is known as the ‘absolute superlative’.

The absolute superlative in French is constructed as follows:

un enfant des plus exaspérants

a most exasperating child

une situation des plus difficiles

a most difficult situation

Ces idées-là sont des plus dangereuses

Those ideas are most dangerous

The use of a plural adjective even when the noun is in the singular will be understood if it is appreciated that un enfant des plus exaspérants, for example, means something like ‘a child from among the most exasperating ones of his kind’.

Alternatively (and very frequently), an intensifying adverb may be used, e.g. un enfant tout à fait exaspérant, Ces idées-là sont extrêmement dangereuses.

Ambiguity may arise in English from the fact that ‘most’ can express either a relative or an absolute superlative. For example, the sentence ‘The situation is most difficult in Paris’ may mean either

(a) ‘It is in Paris that the situation is (the) most difficult’, i.e. we have a relative superlative, C’est à Paris que la situation est le plus difficile (see 170), or

(b) ‘The situation in Paris is extremely difficult’, i.e. we have an absolute superlative, La situation à Paris est des plus difficiles.

In such contexts, care must be taken to select the appropriate French equivalent.

(ii) Unlike English ‘most’, plus is not used in French to express the absolute superlative with adverbs; various other equivalents exist, however, e.g.:

Il conduit avec beaucoup de prudence

He drives most carefully

Elle s’exprime d’une manière extrêmement intelligente

She expresses herself most intelligently

175 (i) Many adjectives of colour and some others are used as nouns with a variety of meanings for which a dictionary must be consulted, e.g.:

| le beau | the beautiful, that which is beautiful |

| le blanc | the white (of an egg, of the eye) |

| un bleu | a bruise |

| le noir | darkness |

176 (ii) Some adjectival nouns originate in expressions of the type noun + adjective; as a result of ellipsis of the noun, the adjective has taken on the function of a noun carrying the meaning of the whole expression, e.g.:

| du bleu | for du fromage bleu, ‘blue cheese’ |

| un (petit) noir | for un café noir, ‘a black coffee’ |

| du rouge | for du vin rouge, ‘red wine’ |

| un complet | for un costume complet, ‘a suit’ |

| la capitale | for la ville capitale, ‘capital (city)’ |

| la majuscule | for la lettre majuscule, ‘capital (letter)’ |

177 (iii) Adjectives can be used as nouns with reference to humans more freely in French than in English. Note in particular that, whereas in English a nominalized adjective with reference to humans is normally plural (e.g. ‘the poor’ = ‘poor people’, ‘the blind’ = ‘blind people’), the fact that French has distinct masculine singular, feminine singular, and plural articles and other determiners (see 23) means that one can have, e.g., un pauvre ‘a poor man’, une pauvre ‘a poor woman’, des pauvres ‘poor people’, le muet ‘the dumb man’, la muette ‘the dumb woman’, cet aveugle ‘this blind man’, cette aveugle ‘this blind woman’, les aveugles ‘blind people’, and, in cases where there are distinct forms for the masculine and feminine adjectives, a distinction in the plural between, for example, les sourds ‘the deaf men’ or ‘the deaf (in general)’ and les sourdes ‘the deaf women’.

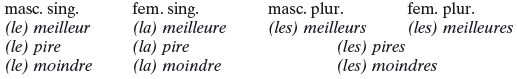

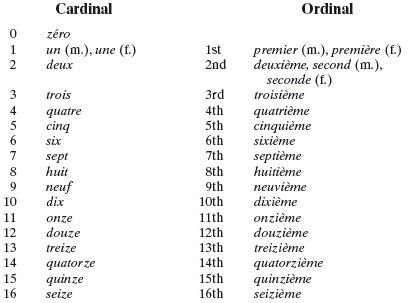

178 Cardinal numbers express numerical quantity, i.e. ‘one, two, three, etc.’, while ordinal numbers express numerical sequence, i.e. ‘first, second, third, etc.’.

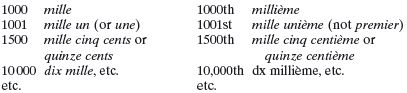

The French cardinals and ordinals are:

179 Notes on pronunciation (for phonetic symbols, see 2):

(a) Cinq is pronounced [s

k] when final (e.g. j’en ai cinq ‘I have five of them’) and [s

k] when final (e.g. j’en ai cinq ‘I have five of them’) and [s k] in liaison (e.g. cinq enfants ‘five children’) but [s

k] in liaison (e.g. cinq enfants ‘five children’) but [s ] before a consonant (see note c) (e.g. cinq jours ‘five days’, though there is an increasing tendency in conversational speech to pronounce [s

] before a consonant (see note c) (e.g. cinq jours ‘five days’, though there is an increasing tendency in conversational speech to pronounce [s k] even there).

k] even there).

(b) Six and dix are pronounced [sis] and [dis] when final (e.g. j’en ai six ‘I have six of them’), [siz] and [diz] in liaison (e.g. dix ans ‘ten years’), and [si] and [di] before a consonant (see note c), (e.g. six jours ‘six days’, dix jours ‘ten days’).

(c) ‘Before a consonant’ in notes a and b relates only to contexts in which the numeral directly governs a following noun (as in cinq jours) or adjective (as in dix beaux livres ‘ten beautiful books’); in contexts such as dix pour cent ‘ten per cent’ this does not apply and the numerals are pronounced [s k, sis, dis].

k, sis, dis].

(d) Neuf is pronounced [nœf] except in the two phrases neuf ans [nœvã] ‘nine years’ and neuf heures [nœvœ r] ‘nine o’clock’, so neuf jours [nœf 3u

r] ‘nine o’clock’, so neuf jours [nœf 3u r] ‘nine days’, neuf arbres [nœf arbr] ‘nine trees’, etc.

r] ‘nine days’, neuf arbres [nœf arbr] ‘nine trees’, etc.

(e) Vingt on its own is pronounced [v ] but it is pronounced [v

] but it is pronounced [v t] not only in liaison (i.e. vingt et un [v

t] not only in liaison (i.e. vingt et un [v t e

t e  ]) but also before a consonant in the numbers ‘22’ to ‘29’ (e.g. vingt-quatre [v

]) but also before a consonant in the numbers ‘22’ to ‘29’ (e.g. vingt-quatre [v tkatr]); but note that the -t of quatre-vingt(s) is never pronounced, not even in quatre-vingt-un.

tkatr]); but note that the -t of quatre-vingt(s) is never pronounced, not even in quatre-vingt-un.

(f) In Belgium and Switzerland, ‘70’ and ‘90’ are septante (pronounced [sεptãt] – contrast sept [sεt] and septième [sεtjεm]) and nonante respectively, and hence septante et un ‘71’, nonanterois ‘93’, etc. However, ‘80’ is usually quatre-vingts though huitante does exist in some parts of Switzerland (but not in Belgium).

180 Remarks:

(a) Hyphens are used in compound numbers except before or after et, cent (or centième), mille (or millième), e.g.:

| vingt-deux, twenty-two | vingt et un, twenty-one |

(b) Et is used in vingt et un ‘21’ and likewise in ‘31’, ‘41’, ‘51’ and ‘61’ and also in soixante et onze ‘71’ (and in ‘121’, ‘237’, ‘371’, etc.), but not in other numerals ending in ‘1’, quatre-vingt-un ‘81’, quatre-vingt-onze ‘91’, cent un ‘101’, deux cent un ‘201’, etc.

(c) Quatre-vingts ‘80’ loses its -s before another numeral, e.g. quatre-vingt-trois ‘83’.

(d) Cent ‘100’ takes a plural -s in round hundreds, e.g. deux cents ‘200’, but not before another numeral, e.g. deux cent trois ‘203’, while mille ‘1000’ never takes an -s, e.g. deux mille ‘two thousand’.

(e) Un is not used with cent ‘100’ or mille ‘1000’, e.g. Il vécut cent ans ‘He lived for a hundred years’, Il possède mille hectares de vignes ‘He owns a thousand hectares of vines’.

(f) The normal form for ‘1100’ is onze cents ‘eleven hundred’ (mille cent is virtually unused); from ‘1200’ to ‘1900’ (and particularly from ‘1200’ to ‘1600’), the forms douze cents ‘twelve hundred’, etc., are preferred to mille deux cents, etc. The same is true of dates of the Christian era, but note in addition that in this case, if the form in ‘one thousand’ is used, then the spelling is mil, e.g. en l’an mil huit cent (no -s – see 182) ‘in the year 1800’ (but ‘the year one thousand’ is l’an mille).

(g) When ‘a thousand and one’ means a large indefinite number (‘umpteen’), it is mille et un(e), e.g. J’ai mille et une choses à faire ‘I have a thousand and one things to do’; note too as an exception, Les Mille et une nuits ‘The Thousand and One Nights (i.e. The Arabian Nights)’.

(h) For the translation of ‘than’ before a numeral, see 167.

(i) Apart from a few fixed expressions, such as (apprendre quelque chose) de seconde main ‘(to learn something) at second hand’, en second lieu ‘secondly’, second and deuxième are interchangeable; the ‘rule’ that second is preferred with reference to the second of two (only) and deuxième when there are more than two can safely be ignored. Note that second is pronounced [s g

g ].

].

181 Note that de is used after un millier ‘(about) a thousand’, un million ‘a million’ and multiples thereof and un milliard ‘a thousand million’ (or a ‘billion’ in American and now generally in British usage – the older sense of ‘a billion’ in British usage is ‘a million million’, which is also now the official definition of un billion in French, though it used to be the equivalent of un milliard), e.g.:

des milliers de dollars

thousands of dollars

cinquante millions de Français

fifty million Frenchmen

deux milliards de dollars

two billion dollars

182 Cardinal numbers (not ordinals as in English) are used:

(a) in dates, e.g.:

| le trois janvier | the third of January |

| le vingt et un juin | the twenty-first of June |

(b) with names of monarchs, popes, etc., e.g.:

| Louis XV (= ‘quinze’) | Louis XV (= ‘the Fifteenth’) |

| Élisabeth II (= ‘deux’) | Elizabeth II (= ‘the Second’) |

| le pape Jean XXIII (= ‘vingt-trois’) | Pope John XXIII (= ‘the Twenty-third’) |

In both such contexts, however, the ordinal premier is used, e.g.:

| le premier mai | the first of May |

| François premier | Francis the First |

The ordinal is invariably used with reference to the arrondissements (districts) of Paris, e.g. habiter dans le seizième (arrondissement) ‘to live in the sixteenth arrondissement’, and usually with reference to floors, e.g. habiter au troisième (étage) ‘to live on the third floor’. It may also be used, as in English, with reference to chapters, etc., e.g. au dixième chapitre ‘in the tenth chapter’. However, as in English the cardinal is normally used in contexts such as the following:

| la page vingt-cinq | page twenty-five |

| le chapitre dix | chapter ten |

| habiter au (numéro) trente | to live in (house) number thirty |

| Je suis au vingt-quatre | I’m in (room) number twenty-four |

Note that in such contexts, i.e. when they serve as the equivalent of ordinals, quatre-vingt ‘80’ and cent ‘100’ (in the plural) do not take a final -s (contrast 178, and 180 c and d), e.g.:

| à la page quatre-vingt | on page eighty |

| habiter au numéro trois cent | to live in number three hundred |

| l’an sept cent | the year seven hundred |

(For ‘every other, every third’, etc., see 317,ii,b.)

183 Conversely to what happens in English, cardinals precede premier ‘first’ and dernier ‘last’, e.g.:

| les dix premières pages | the first ten pages |

| les trois derniers mois | the last three months |

184 For ‘both’, ‘all three’, etc., see 317,ii,f.

185 The following ten nouns ending in -aine express an approximate number:

une huitaine, about eight

une dizaine, about ten

une douzaine, a dozen

une quinzaine, about fifteen

une vingtaine, a score, about twenty

une trentaine, about thirty

une quarantaine, about forty

une cinquantaine, about fifty

une soixantaine, about sixty

une centaine, about a hundred

e.g. J’ai écrit une vingtaine de lettres

I’ve written about twenty letters

Une huitaine is used particularly in the expression une huitaine de jours (i.e. ‘a week’) and une quinzaine whether or not followed by de jours frequently means ‘a fortnight’. As in English, une douzaine ‘a dozen’ can mean ‘precisely twelve’ in such expressions as une douzaine d’œufs ‘a dozen eggs’. The terms trentaine, quarantaine, cinquantaine and soixantaine can refer to age in such expressions as atteindre la quarantaine ‘to reach the age of forty’, Elle a dépassé la cinquantaine ‘She is over fifty’.

Note that similar forms based on other numerals either do not exist or are no longer in use (apart from une neuvaine which is used only in the sense of ‘novena’).

186 French has no adverbs to express numerical frequency (corresponding to English ‘once, twice, thrice’). The word fois ‘time’ is used, e.g. une fois ‘once’, deux fois ‘twice’, trente-six fois ‘thirty-six times’. Note the construction dix fois sur vingt ‘ten times out of twenty’.

187 The multiplicatives double ‘double, twofold’, triple ‘triple, treble, threefold’, quadruple ‘quadruple, fourfold’, centuple ‘hundredfold’ are used both as adjectives (in which case they often precede the noun), e.g. une consonne double ‘a double consonant’, un triple menton ‘a treble chin’, and (preceded by the definite article) as nouns, e.g. le double de ce que j’ai payé ‘double what I paid’, le quadruple de la récolte de l’an dernier ‘four times (as much as) last year’s harvest’.

Apart from the forms quoted above, only the following exist, and some of these are not much used: quintuple ‘fivefold’, sextuple ‘sixfold’, septuple ‘sevenfold’, octuple ‘eightfold’, nonuple (very rarely used) ‘ninefold’, décuple ‘tenfold’.

188 A ‘half’ is either (un) demi or la moitié, but the two are by no means interchangeable (and see also 189). We can distinguish three types of function, viz. (i) as nouns, (ii) as adjectives, (iii) as adverbs:

(i) Apart from a few contexts in which it is a nominalized adjective (see ii,c, below), un demi exists as a noun only as a mathematical term, e.g. Deux demis font un entier ‘Two halves make a whole’. Otherwise, la moitié must be used (and note that, when it is the subject of the verb, the verb may be either singular or plural, depending on the sense – the same is also true of other fractions), e.g.:

Il n’a écrit que la moitié de son roman

He has only written half his novel

couper une orange en deux moitiés

to cut an orange into two halves

La moitié de la ville a été inondée

Half the town was flooded

La moitié de mes amis habitent à Paris

Half my friends live in Paris

la première (seconde) moitié

the first (second) half

(ii) Demi occurs in the following circumstances:

(a) before a noun in the sense of ‘half (a) …’; it is then invariable and is linked to the noun by a hyphen, e.g. un demi-pain ‘half a loaf’, un demi-frère ‘a half-brother’, une demi-heure ‘half an hour’, une demi-bouteille ‘half a bottle’, des demi-mesures ‘half-measures’;

(b) after the noun and preceded by et, meaning ‘… and a half’; it is then written as a separate word and takes an -e if the noun is feminine, e.g. un kilo et demi ‘a kilo and a half, one and a half kilos’, une heure et demie ‘an hour and a half, one and a half hours, half past one’, trois heures et demie ‘three and a half hours, half past three’;

(c) with an implied noun (as in a above), in contrast to a noun expressing a whole object, e.g. Vous voulez un pain? Non, un demi ‘Do you want a loaf? No, a half (half a loaf)’; note (in contrast to une demi-bouteille, etc., see a above) that demi takes -e in agreement with a feminine noun when the noun itself is omitted, e.g. Nous allons commander une bouteille de vin? – Une demie suffira ‘Shall we order a bottle of wine?’ ‘A half (bottle) will be enough’. Note too the following instances in which the noun has been completely dropped and the adjective has therefore become fully nominalized (see 176):

un demi ‘glass of beer’ (originally un demi-litre, but now contains less)

un demi ‘half-back’ (in football – for un demi-arrière)

(iii) As adverbs, à demi and à moitié are in most cases interchangeable (but see below), in particular:

(a) before an adjective or participle, e.g.:

à demi plein/vide, à moitié plein/vide

half full/empty

à demi ouvert/pourri, à moitié ouvert/pourri

half open/rotten

(b) after a verb, e.g.:

ouvrir la porte à demi/à moitié

to half-open the door

Vous avez fait le travail à demi/à moitié

You have (only) half done the work

remplir un verre à demi/à moitié

to half-fill a glass

Note, however, the use of à moitié (but not of à demi) in a small number of expressions with nouns, in particular à moitié prix ‘(at) half-price’ and à moitié chemin ‘half-way’ (but à mi-chemin, see below, is more usual). Moitié (without à) also occurs in various other expressions such as moitié moitié ‘half-and-half, fifty-fifty’, (diviser quelque chose) par moitié ‘(to divide something) in half, in two’, être pour moitié dans quelque chose ‘to be half responsible for something’ (for other such expressions, consult a good dictionary).

189 The old noun mi ‘a half’ is still used adverbially in such constructions as mi pleurant et mi souriant ‘half weeping and half smiling’, mi-fil et mi-coton ‘half linen and half cotton’; in the expression mi-clos ‘half-shut’, and in a number of expressions with à mi including the following (for others, consult a dictionary):

à mi-chemin, half-way

à mi-distance, half-way, midway

à mi-hauteur, half-way up

à mi-pente, half-way up or down the slope

(travailler) à mi-temps, (to work) half-time

à mi-voix, in an undertone

190 ‘A third’ and ‘a quarter’ are un tiers and un quart respectively, e.g.:

| un tiers des votants | one third of those voting |

| un quart d’heure | a quarter of an hour |

La bouteille est aux trois quarts vide

The bottle is three-quarters empty

Other fractions have (as in English) the same form as the ordinals, e.g. un cinquième ‘a fifth’, sept huitièmes ‘seven eighths’, un centième ‘a hundredth’, etc.

191 When a fraction refers to part of a specific whole (i.e. to one introduced by the definite article or by a demonstrative or possessive determiner), French uses the definite article where English uses the indefinite article or (especially in the plural) no article, e.g.:

Il a perdu le quart de ses biens

He lost a quarter of his possessions

la moitié de la classe

half (of) the class

les sept huitièmes de la population

seven eighths of the population

192 The decimal system as used in France is based not on the point but on the comma, and the figures coming after the comma are often expressed as if they were whole numbers, e.g. 2.35 ‘two point three five’ becomes 2,35 deux virgule trente-cinq.

Introduction

193 Personal pronouns in French are either ‘conjunctive’ or ‘disjunctive’.

Conjunctive pronouns (see 198–213) are used only in direct association with a verb. They include (a) subject pronouns, e.g. Je vois ‘I see’, (b) direct and indirect object pronouns, e.g. (Pierre) la connaît ‘(Peter) knows her’, (Marie) leur écrit ‘(Mary) writes to them’, and (c) the adverbial pronouns y (see 200) and en (see 201).

Disjunctive pronouns (see 215–220) usually stand independently of the verb, e.g. Moi (je sais) or (Je sais) moi ‘I know’, avec eux ‘with them’, though they are directly associated with the verb in imperative constructions such as Pardonnez-moi ‘Forgive me’ (see 207).

194 Je ‘I’ and nous ‘we’ are known as the first person singular and the first person plural respectively; tu ‘you’ and vous ‘you’ (see 196) are the second person singular and the second person plural respectively; il ‘he, it’ and elle ‘she, it’ are the third persons singular, masculine and feminine, and ils and elles ‘they’ are the third persons plural, masculine and feminine.

195 Je can be either masculine or feminine, depending on the sex of the speaker, e.g. Je suis heureux (masc.), Je suis heureuse (fem.) ‘I am happy’. Likewise, nous can be either masculine or feminine, e.g. Nous sommes heureux/heureuses ‘We are happy’ (when nous includes persons of both sexes, the masculine agreement is used).

Similarly with the direct object forms, e.g. Il me croit intelligent(e) ‘He considers me (masc., fem.) intelligent’, Il nous croit intelligent(e)s ‘He considers us (masc., fem.) intelligent’.

196 Tu refers to one person only and is normally used only when addressing a friend, a relative, a child, God, or an animal; used in other contexts it can (and can be intended to be) offensive. Note that, whereas the corresponding English form thou has long since gone out of use (except in some dialects and sometimes in poetic or religious style), the use of tu is on the increase, particularly among young people. It may take either masculine or feminine agreement, depending on the sex of the person addressed, e.g. Tu es heureux (masc.)/heureuse (fem.) ‘You are happy’; likewise with the direct object pronoun te, e.g. Il te croit intelligent(e) ‘He considers you (masc., fem.) intelligent’.

Those to whom one does not say tu are addressed as vous, which is therefore either singular or plural depending on whether one is addressing one person or more than one; whether it is singular or plural makes no difference to the verb, but adjectives and participles vary both for gender and for number, e.g. Vous êtes fou (masculine singular)/folle (feminine singular)/fous (masculine plural)/folles (feminine plural) ‘You’re crazy’. Likewise with the direct object pronoun, e.g. Il vous croit fou (masc. sing.)/folle (fem. sing.)/fous (masc. plur.)/folles (fem. plur.) ‘He thinks you crazy’. (As with nous, when vous includes persons of both sexes, the masculine agreement is used.)

197 Masculine nouns, whether relating to humans, animals, abstractions or inanimate objects, are referred to as il and feminine nouns as elle; il and elle therefore both mean ‘it’ as well as ‘he’ and ‘she’ respectively, e.g. Où est ma cuiller? Elle est sur la table ‘Where is my spoon? It’s on the table’. When ‘they’ refers to persons of both sexes or to nouns of both genders, ils is used.

‘Impersonal’ il is the equivalent of the English impersonal ‘it’ or, in some contexts, of English ‘there’ in such expressions as il pleut ‘it is raining’, il fait chaud ‘it’s hot’, il est trois heures ‘it is three o’clock’, il faut ‘it is necessary’, il semble que ‘it seems that’, il y a ‘there is, there are’, il soufflait un vent du nord ‘there was a north wind blowing’ (see 343). For the distinction between il est and c’est, see 253–261.

198 (i) The forms of the conjunctive personal pronouns are:

| subject | direct | indirect |

| object | object | |

| je, I | me, me | me, to me |

| tu, you | te, you | te, to you |

| il, he, it | le, him, it |  |

| elle, she, it | la, her, it | |

| nous, we | nous, us | nous, to us |

| vous, you | vous, you | vous, to you |

| Us, they (masc.) | les, them | leur, to them |

| elles, they (fem.) | les, them | leur, to them |

(For the terms ‘direct object’ and ‘indirect object’, see 17, 18 and 21.)

Je, me, te, le and la become j’, m’, t’ and l’ before a verb beginning with a vowel or mute h and before y or en, e.g. J’arrive ‘I arrive’, J’y habite ‘I live there’, M’aimes-tu? ‘Do you love me?’, Il t’en envoie ‘He’s sending you some’, Il l’achète ‘He buys it’.

(ii) The indirect object pronouns are used:

(a) with such verbs as dire ‘to say’, donner ‘to give’, and other verbs of comparable meaning, e.g. avouer ‘to admit’, confier ‘to entrust’, envoyer ‘to send’, offrir ‘to offer’, parler ‘to speak’, recommander ‘to recommend’, rendre ‘to give back’:

| Il me dit que c’est vrai | He tells me it’s true |

| Donnez-lui cette lettre | Give him this letter |

| Il va nous l’envoyer | He is going to send it to us |

| Je vous recommande ce restaurant | I recommend this restaurant to you |

(b) with a number of other verbs, among the most common being appartenir ‘to belong’, écrire ‘to write’, falloir ‘to be necessary’, paraître ‘to seem’, pardonner ‘to forgive’, plaire ‘to please’, sembler ‘to seem’, e.g.:

| Ce livre m’appartient | This book belongs to me |

| Cela me paraît difficile | That seems difficult to me |

| Il lui faut un bureau | He needs an office |

| Je leur pardonne tout | I forgive them everything |

| Cette robe vous plaît? | Do you like this dress? |

For verbs taking à + the disjunctive pronoun (e.g. Je pense à vous ‘I am thinking of you’), see 220.

(iii) With reference to things, the indirect object is often expressed by y rather than by lui or leur – see 200.

199 As a reflexive pronoun (for reflexive verbs see 379–381), se replaces all the third person pronouns, singular and plural (i.e. le, la, les, lui, leur), e.g.:

| elle se lave | she washes (herself) |

| ils s’écrivent | they write to one another |

In the first and second persons, the forms me, te, nous and vous also function as reflexive pronouns, e.g.:

| je me lave | I wash (myself) |

| tu te laves | you wash (yourself) |

| nous nous écrivons | we write to each other |

| vous vous fatiguez | you are tiring yourselves |

For the reciprocal use of reflexive pronouns see 292.

For the full conjugation of a reflexive verb see 381.

For the use of soi see 219.

200 (i) The adverbial conjunctive pronoun y corresponds to the preposition à + noun, when the noun refers to an animal, a thing, a place or an abstract idea (or any of these in the plural), e.g. Je réponds à la lettre ‘I reply to the letter’ and J’y réponds ‘I reply to it’, Il travaille à Paris ‘He works in Paris’ and Il y travaille ‘He works there’. (On y with reference to people, see ii below.)

(a) It frequently has the meaning ‘there’, e.g.:

Connaissez-vous Dijon? – Oui, j’y suis né

Do you know Dijon? – Yes, I was born there

However, it can be so used only to refer back to a place mentioned or implied in what has gone before. It does not have a demonstrative value, i.e. it does not, so to speak, ‘point’ to the place indicated by ‘there’ (or, to put it differently, it does not express the idea of ‘there’ as opposed to ‘here’); in such circumstances, là is used, e.g. Ton parapluie est là ‘Your umbrella is there’.

(b) With many verbs, y has the meaning ‘to it, to them’, e.g.:

Il s’y accrochait

He was hanging on to it (or them)

Je suis flatté de cet honneur, d’autant plus que je n’y avais jamais aspiré

I am flattered by this honour, the more so since I had never aspired to it

Ses observations ne me dérangent pas : je n’y fais pas attention

His remarks don’t bother me: I pay no attention to them

In such instances as the following, the French verb takes à where the corresponding English verb either has a direct object (e.g. renoncer à quelque chose ‘to give something up’, succéder à ‘to succeed, follow’) or takes a preposition other than ‘to’ (e.g. viser à ‘to aim at’, penser à, songer à, réflèchir à ‘to think about’):

Vous ne fumez plus? – Non, j’y ai renoncé

Don’t you smoke any more? – No, I’ve given it up

la IIIe République et tous les régimes qui y ont succédé

the Third Republic and all the regimes that succeeded it

Il y réfléchit

He is thinking about it (considering it)

Note that, with reference to people, these verbs take à and the disjunctive pronouns, lui, elle, eux, elles, not the conjunctive indirect object pronouns, lui and leur, e.g. Elle a renoncé à lui ‘She has given him up’, Je pensais à eux ‘I was thinking of them’.

(c) Y is sometimes the equivalent of sur and a noun, e.g. écrire sur une feuille de papier ‘to write on a sheet of paper’ and Il y écrit une lettre d’amour ‘He’s writing a love-letter on it’, Je compte sur sa discrétion ‘I am counting on his discretion’ and Vous pouvez y compter ‘You can count on it’.

(d) Y sometimes corresponds to à + a verb, as in obliger quelqu’un à faire quelque chose, hence:

Ne partez pas. Rien ne vous y oblige

Don’t go. Nothing obliges you to (do so)

(ii) Y sometimes refers to people, particularly in substandard French, e.g. J’y pense souvent ‘I often think of him (her, them)’, for Je pense souvent à lui (à elle, à eux, à elles). This construction occasionally occurs in literary French, especially in that of a somewhat archaic kind, but it should not be imitated.

(iii) Lui and leur are sometimes used instead of y with reference to animals, things or abstract ideas, particularly:

(a) when it is necessary to make it clear that the meaning is ‘to it’ or ‘to them’ and not ‘there’, e.g.:

Les dames de la ville lui donnaient leur clientèle (Theuriet)

The ladies of the town gave it [= a shop] their custom

or (b) when the noun is to some extent personified, e.g.:

dois votre amitié

your friendship

201 (i) The conjunctive pronoun en (not to be confused with the preposition en which is a totally different word, see 654–658) corresponds to the preposition de + a noun, especially with reference to animals, things, places and abstract ideas, e.g. Nous parlons souvent de votre visite ‘We often talk about your visit’ and Nous en parlons souvent ‘We often talk about it’, Il est arrivé hier de Paris ‘He arrived yesterday from Paris’ and Il en est arrivé hier ‘He arrived from there yesterday’. (On en with reference to people, see ii below.)

(ii) In partitive constructions, it serves as a pronominal equivalent of de + a noun, with the value of ‘some of it (or of them)’, or ‘any of it (or of them)’; and note that, though ‘of it, of them’ is frequently omitted in English, en must be inserted in French, e.g.:

Avez-vous du pain? – Oui, j’en ai acheté

Have you any bread? – Yes, I’ve bought some

Voulez-vous de la bière? – Oui, s’il y en a

Do you want some beer? – Yes, if there is any

Si vous voulez des billets, je peux vous en donner

If you want tickets, I can give you some

Il n’y en a pas

There isn’t (or aren’t) any

Il a plus d’argent qu’il n’en veut

He has more money than he wants

This construction frequently occurs with numerals and expressions of quantity, e.g.:

Combien de timbres pouvez-vous me prêter? – Je vais vous en prêter dix

How many stamps can you lend me? – I’ll lend you ten

Voulez-vous du fromage? – J’en prends cent grammes

Do you want (any) cheese? – I’ll take a hundred grammes

Note that, in this construction, en is used (and must be used) with reference to people just as with reference to animals, things, etc. (cf. i above and iv below), e.g.:

Combien d’enfants avez-vous? – J’en ai quatre

How many children have you? – I have four

(iii) In contexts such as the following, where in English one often (but not always) has the option of using either ‘of it, of them’ or the possessive determiner ‘its, theirs’, en is used in French, e.g.:

Je n’en aime pas la forme

I don’t like the shape of it (or its shape)

Regarde ces fleurs! La couleur en est si jolie

Look at those flowers! The colour of them (their colour) is so pretty

(iv) Except in partitive constructions (see ii above), de lui, d’elle, d’eux and d’elles rather than en are normally used with reference to people, e.g.:

Il rêve d’elle chaque nuit

He dreams of her every night

J’ai reçu de lui une très longue lettre

I have had a very long letter from him

However, en is used much more widely than y (see 200,ii) with reference to people, not only in colloquial French (e.g. Il en rêve chaque nuit ‘He dreams of her every night’) but also in the literary language, e.g.:

Il s’efforçait de lier conversation avec lui, comptant bien en tirer quelques paroles substantielles (A. France)

He tried to engage him in conversation, fully expecting to extract from him a few words of substance

Je le vois rarement, mais j’en reçois de très longues lettres

I rarely see him, but I get very long letters from him

On n’a d’ouverture sur un être que si on en est aimé (Chardonne)

One can have no real understanding of another person unless one is loved by him (or by her)

202 Conjunctive pronouns are used in French in such contexts as the following, where their equivalents may be merely implied in English:

Qui vous l’a dit?

Who told you?

Quand allez-vous à Paris? – J’y vais demain

When are you going to Paris? – I’m going (there) tomorrow

(For examples with en, see 201,ii.)

The position of conjunctive personal pronouns

Subject

203 The subject pronoun normally comes before the verb; however, it follows the verb

(i) in certain types of questions (see 583–584, 589–592)

(ii) in certain non-interrogative constructions (see 476–478, 596, 599–600).

As a rule the subject pronoun is best repeated with each verb; but, provided both verbs are in the same tense, it may be omitted with et, mais and ou (see examples in 210), and generally is with ni ‘nor’ (see 571).

No subject is expressed with verbs in the imperative (see 514).

Pronouns other than subject pronouns

204 Except with the affirmative imperative (see 207), the pronouns stand immediately before the verb of which they are the object, e.g.:

| Je t’aime | I love you |

| La connaissez-vous? | Do you know her? |

| Mon frère leur écrit souvent | My brother often writes to them |

| J’en prends six | I’ll take six of them |

| Nous n’y allons pas | We are not going there |

| Ne les perdez pas | Don’t lose them |

| Nous voulons les vendre | We want to sell them |

(In the last of the above examples, ‘them’ is the object of ‘sell’ not of ‘wish’ and so, in accordance with the rule, comes immediately before the infinitive vendre ‘to sell’.)

In the case of compound tenses (see 448–456) the pronouns come before the auxiliary and are never placed immediately before the past participle, e.g.:

| Je vous ai écrit | I have written to you |

| Ne les avez-vous pas trouvés? | Haven’t you found them? |

| Mon père y est allé | My father has gone there |

205 In a negative sentence, the ne stands immediately before the object pronouns, e.g. Je ne les aime pas ‘I don’t like them’.

206 When there is more than one object pronoun, they stand in the following order:

| 1 | me, te, se, nous, vous |

| 2 | le, la, les |

| 3 | lui, leur |

| 4 | y |

| 5 | en |

Examples:

| Il me les donne | He gives me them (them to me) |

| Je le lui ai donné | I gave it to him (to her) |

| Les y avez-vous vus? | Did you see them there? |

| Vous en a-t-il offert? | Did he offer you any? |

| Ne me l’envoyez pas | Don’t send it to me |

| Ne les lui donnez pas | Don’t give them to him |

Note:

(a) that is not possible for more than one member of any one of groups 1 to 3 above to occur with the same verb (see 208)

(b) that, though it is possible for up to three of the above pronouns to occur together provided they are from different groups (e.g. Je m’y en achète ‘I buy some for myself there’), in practice this very rarely happens.

207 With the affirmative imperative (see 514):

(a) all pronouns follow the verb

(b) moi and toi are used instead of me and te except with en and y (see below)

(c) direct object precedes indirect object

(d) y and en come last

(e) except for elided forms (m’, t’, l’), pronouns are linked to the verb and to one another by hyphens.

Examples:

| Croyez-moi | Believe me |

| Prends-en | Take some (of it, of them) |

| Donnez-le-moi | Give it to me |

| Menez-nous-y | Take us there |

| Offrez-lui-en | Offer him some |

| Donnez-m’en | Give me some |

| Menez-l’y | Take him (or her) there |

| Va-t’en! | Go away! |

Note, however, that the theoretically possible forms m’y and t’y are avoided in practice after an imperative, as are, in the literary language and in careful speech, the alternatives y-moi and y-toi that occur in colloquial speech (e.g. Menez-y-moi ‘Take me there’). The solution is to use a different construction, e.g. Voulez-vous m’y mener? ‘Will you take me there?’ or Pourriez-vous m’y mener? ‘Could you take me there?’

208 It is not possible to combine:

(i) any two of me, te, se, nous, vous (see 206, note a), or

(ii) any of me, te, se, nous, vous as direct object with lui or leur as indirect object.

In circumstances that might seem to require one of these impossible constructions, the direct object pronoun follows the ordinary rule but the indirect object is expressed by à ‘to’ and a disjunctive pronoun (see 215–220), e.g.:

Il vous présentera à moi

He will introduce you to me

Voulez-vous me présenter à elles?

Will you introduce me to them?

Ils se sont rendus à moi

They surrendered to me

Nous ne nous rendrons pas à eux

We shall not surrender to them

Présentez-moi à lui

Introduce me to him (to her)

209 When an infinitive is governed by a modal verb (e.g. devoir, pouvoir, vouloir) or some other verb such as aller, compter, oser, préférer (see 529), any conjunctive pronouns precede the infinitive, e.g.:

| Je veux lui écrire | I want to write to him |

| Il doit y aller demain | He is to go there tomorrow |

| Vous allez le regretter | You are going to regret it |

| Il ose me contredire | He dares to contradict me |

| Je compte vous les envoyer demain | I expect to send them to you tomorrow |

(In a somewhat archaic style, which should not be imitated, the pronoun sometimes precedes the modal verb, e.g. Ils la peuvent apercevoir (H. Bordeaux) ‘They can see her’.)

For the constructions used when faire, laisser, envoyer, verbs of the senses, and certain other verbs, are followed by an infinitive, see 430–438.

210 In English, the same pronoun may serve as the direct or indirect object of more than one verb, e.g. ‘He loves and understands her’. In such circumstances, conjunctive pronouns in French are repeated with each verb, e.g.:

| Il l’aime et la comprend | He loves and understands her |

(In compound tenses, in which the pronoun always precedes the auxiliary verb, see 204, the pronoun cannot be repeated if the auxiliary is not repeated, e.g. Il l’a toujours aimée et respectée ‘He has always loved and respected her’.)

211 French makes much greater use than English of conjunctive pronouns referring either back or forward to nouns occurring in the same clause.

(i) This is normal (i.e. the conjunctive pronoun should be used) when attention is drawn to any element in the sentence by bringing it forward from its more usual position after the verb, e.g.:

Ce poème je le connais par cœur

I know this poem by heart

A mon cousin je ne lui écris jamais

I never write to my cousin

A Paris j’y vais souvent

I often go to Paris

De ces romans-là j’en ai plusieurs

I have several of those novels

(In examples such as these last three, the introductory preposition is sometimes omitted.)

(ii) In spoken French, anticipation of a direct or indirect object or of a prepositional phrase (introduced by à or de) by a conjunctive pronoun is very frequent, e.g.:

Je la connais ta soeur

I know your sister

Je lui écris souvent à mon frère

I often write to my brother

Il n’y va jamais à Paris

He never goes to Paris

J’en ai plusieurs de ces romans-là

I have several of those novels

See also 602, ‘Dislocation and fronting’.

212 Le frequently refers not to a specific noun but to a concept. This may be:

(i) a quality or status expressed by an adjective, participle or noun (but see also 213), e.g.:

En sont-ils contents? – Je suis sûr qu’ils le sont

Are they pleased with it? – I am sure they are

Ce livre qui vient d’être publié n’aurait pas dû l’être

This book which has just been published ought not to have been

Est-elle étudiante? – Elle le sera l’année prochaine

Is she a student? – She will be next year

Cet édifice était autrefois une église mais il ne l’est plus

This building used to be a church but it is not (one) any more

(ii) the idea expressed in a previous clause, e.g.:

Est-ce qu’il arrive aujourd’hui? – Je l’espère

Is he arrive today – I hope so

Si vous comptez réserver des places, je vous conseille de le faire sans tarder

If you want to book seats, I advise you to do so without delay

Je viendrai dès qu’on me le permettra

I shall come as soon as I am allowed to

Son explication n’est pas très lucide, je l’avoue

His explanation is not very clear, I admit

Note that after comme and after comparatives the use of le is optional, e.g.:

Je suis essoufflé comme vous (le) voyez

I am out of breath, as you see

Il est plus intelligent que je ne (le) croyais

He is more intelligent than I thought

213 The literary language sometimes uses the pronouns le, la, les, with the verb être (or occasionally with other verbs such as rester ‘to remain’) to refer back to a noun used with the definite article or another ‘definite’ determiner (such as a demonstrative, interrogative or possessive). The pronoun agrees with this noun in gender and number, e.g. Tu devrais être ma femme, n’est-ce pas fatal que tu la sois un jour? (Zola) ‘You ought to be my wife, is it not inevitable that one day you will be?’ (la agrees with ma femme). This, however, is an exclusively literary construction. In speech, one would be likely either to use the invariable le (see 212,i), e.g.:

Elle n’est pas sa femme et elle ne le sera jamais

She is not his wife and never will be

or to use some other construction, such as repeating the noun, e.g.:

Vous êtes son fils? – Oui, je suis son fils

Are you his son? – Yes, I am

214 Note, on the other hand, that in contexts such as the following where English uses an anticipatory ‘it’ with reference to a following clause or infinitive serving as the direct object of the preceding verb, there is no equivalent pronoun in French:

J’estime essentiel que tu lui écrives

I consider it essential that you write to him

J’ai entendu dire qu’il va démissionner

I have heard it said that he is going to resign

Je crois préférable de ne pas y aller

I think it best not to go there

Il a jugé bon de partir tout de suite

He thought it advisable to leave at once

Il s’est mis dans la tête d’aller à Paris

He got it into his head to go to Paris

This is particularly common after a verb of thinking + an adjective, as in some of the above examples.

215 The disjunctive pronouns are:

| moi, I, me | lui, he, him |

| toi, you | elle, she, her |

| nous, we, us | eux, they, them (masc.) |

| vous, you | elles, they, them (fem.) |

They can be combined with -même(s) as follows:

| moi-même, myself | nous-mêmes, ourselves |

| toi-même, yourself | vous-même, yourself |

| vous-mêmes, yourselves | |

| lui-même, himself | eux-mêmes, themselves (masc.) |

| elle-même, herself | elles-mêmes, themselves (fem.) |

as in Je le ferai moi-même ‘I’ll do it myself’.

In addition to these there is the reflexive disjunctive pronoun soi (see 219).

The disjunctive pronouns can be used either as a subject of a verb (e.g. Mon frère et moi partons demain ‘My brother and I are leaving tomorrow’), or as the object (e.g. Je la connais, elle ‘I know her’), or after prepositions (e.g. avec eux ‘with them’) (see succeeding paragraphs).

216 The disjunctive pronouns (other than soi, see 219) are used in the following circumstances:

(i) whenever the personal pronoun is to be emphasized (see also 602, ‘Dislocation’) or is contrasted with another pronoun or noun; in such circumstances, the disjunctive pronouns are used in addition to the conjunctive pronouns (this applies even when the two forms are the same, i.e. to nous and vous) (but see also 217), e.g.:

Toi, tu ne peux pas venir or Tu ne peux pas venir, toi

You can’t come

Mon frère part demain mais moi je reste ici

My brother is leaving tomorrow but I’m staying here

Vous, vous ne pouvez pas comprendre

You can’t understand

Il ose m’accuser, moi!

He dares to accuse me!

Lui, je l’aime beaucoup

I like him very much

If the conjunctive pronoun expresses an indirect object, the disjunctive is preceded by à, e.g.:

Il te l’a donné à toi

He gave it to you

Je leur obéirai à eux mais pas à mon oncle

I will obey them but not my uncle

Note too the use of disjunctive nous, vous + autres as emphatic forms, particularly when there is an expressed implied distinction between ‘us’ or ‘you’ on the one hand and some other group (or other people in general) on the other, e.g.:

Nous autres Français, nous mangeons beaucoup de pain

We French eat a lot of bread

Vous n’êtes jamais contents, vous autres fermiers

You farmers are never content

Nous n’aimons pas ça, nous autres

We do not like that

(ii) when there are two or more coordinate subjects (i.e. the type ‘X and Y’ or ‘X, Y and Z’), e.g.:

Mon frère et moi nous partons demain

My brother and I are leaving tomorrow

Lui et moi nous savons que ce n’est pas vrai

He and I know it isn’t true

Je croyais que ton frère et toi vous n’arriveriez jamais

I thought your brother and you would never arrive

Son père et lui ne s’entendent pas très bien

His father and he don’t get on very well together

In this construction, the conjunctive pronouns nous and vous are usually inserted (as in the first three examples above), particularly in speech, though Mon frère et moi partons demain, etc., are also possible, especially in writing. This insertion of the conjunctive pronoun is less usual, especially in writing, with the third person pronouns ils and elles (cf. the fourth example above where no conjunctive pronoun is used).

When the word-order is inverted (i.e. the subject follows the verb) in questions or after one of the adverbs or adverbial expressions that cause inversion (see 600), the conjunctive pronoun must be used, e.g.:

Ton frère et toi comptez-vous partir demain?

Do you and your brother expect to leave tomorrow

Sans doute Anne et lui en seront-ils contents

Anne and he will doubtless be pleased

(iii) as the complement of c’est, c’était, etc., e.g. C’est moi ‘It’s me’ (see also 255 and 258)

(iv) after prepositions, e.g. pour moi ‘for me’, sans lui ‘without him’, avec vous ‘with you’

(v) after ne … que ‘only’, e.g.:

Je ne connais que lui

I only know him (i.e. him only)

Je ne le dis qu’à toi

I’m only telling you (you only)

(vi) as the subject or object of an unexpressed verb:

(a) subject (note that in the corresponding English utterances a verb, which may be just the verb ‘to do’ standing in for another verb, often is expressed), e.g.:

Qui a dit ça? – Moi

Who said that? – I did (or Me)

Qui le fera? – Lui

Who will do it? – He will

Je suis plus grand que toi

I am taller than you (are)

Jean va peut-être rester, mais moi non (or moi pas)

John may be staying, but I’m not

(b) object, e.g.:

Qui a-t-il vu? – Toi

Whom did he see? – You

(vii) as the subject of an infinitive in exclamations (see 429), e.g.:

| Lui, nous trahir! | He betray us! |

217 The third person disjunctive pronouns are sometimes used as the direct subjects of a verb (i.e. in the absence of the corresponding conjunctive pronoun), e.g.:

Les autres l’ignoraient, mais lui le savait

The others were unaware of it, but he knew