542 We shall discuss negation under the following headings:

A: Negation with a verb

B: The negative conjunction ni ‘neither, nor’

C: Negation of an element other than a verb

543 Negation with a verb is expressed by the use of ne (or n’ before a vowel or mute h) before the verb and, in most cases, of another element which may be a determiner (aucun, nul ‘no, not any’), a pronoun (personne ‘nobody’, rien ‘nothing’, aucun, nul), an adverb (aucunement, nullement, ‘in no way, not at all’, guère ‘hardly, scarcely’, jamais ‘never’, plus ‘(no) longer’, que ‘only’, and what are often termed the negative particles pas and point ‘not’). Some of these elements always follow the verb, others may either precede or follow depending on meaning or on the degree of emphasis they carry. All are discussed at greater length below.

Negation is a field where it is essential to take account of medium and register (see 13). Note in particular the mainly literary use of point (545), of nul (547) and of nullement (548), the omission of ne in informal registers (556), the use of ne on its own in the literary language (561) and the use or non-use of ne after avant que and à moins que (566).

Note that faire must not be used as the equivalent of ‘do’ in negative constructions, e.g.:

Ils ne parlent pas français

They do not speak French

For the use of ne alone, see 559–567.

Ne and another element

ne … pas, ne … point ‘not’

544 (i) The normal way of making a verb negative is to use ne … pas. Pas comes immediately after the verb or, in compound tenses, after the auxiliary (but see also ii below), e.g.:

Je ne viens pas

I am not coming

Il n’est pas venu

He has not come

Mon frère ne la connaissait pas

My brother did not know her

However, ne pas come together before an infinitive, e.g.:

Je préfère ne pas le voir

I prefer not to see him

Je suis content de ne pas le lui avoir dit

I am glad not to have told him

(The construction ne + infinitive + pas exists but is archaic and should not be imitated.)

(ii) Nothing can come between the verb (or auxiliary) and pas except the subject pronoun in a negative-interrogative clause or certain adverbs, mainly adverbs of affirmation or doubt (see 627–628), such as certainement ‘certainly’, même ‘even’, peut-être ‘perhaps’, probablement ‘probably’, sûrement ‘certainly’ and the adverbial phrase sans doute ‘doubtless’, e.g.:

Ne vient-il pas?

Isn’t he coming?

Ne vous l’avais-je pas dit?

Had I not told you?

Il ne viendra certainement pas

He certainly won’t come

II ne m’a même pas regardé

He did not even look at me

Vous ne l’avez peut-être pas vu

Perhaps you did not see him

Il ne la connaissait probablement pas

He probably didn’t know her

The only items that can come between ne and the verb are the conjunctive personal pronouns, me, le, vous, etc. – see 387,ii,d, and some of the examples quoted above.

(iii) The only case in which pas can precede the verb is when it forms part of the expression pas un (seul) ‘not (a single) one’ as subject of the verb, e.g.:

De tous mes amis, pas un (seul) n’a voulu m’aider

Of all my friends, not one was willing to help me

Pas un oiseau ne chantait dans la forêt

Not a single bird was singing in the forest

545 Some grammars state that point expresses a ‘stronger’ negation than pas (some, indeed, go so far as to translate it as ‘not at all’). This is not so. For ‘not at all’, some such expression as pas du tout or absolument pas must be used. Point nowadays is used mainly by writers who wish to give a slightly archaic or a provincial flavour to their French. Many modern writers never use it and foreigners are well advised to avoid it altogether.

Note that, although (subject to the above remarks) point could replace pas in any of the examples given in 544,i and ii, it cannot be substituted for pas in pas un – see 544,iii.

546 aucun ‘no, not any, etc.’

Aucun is used:

(i) In the singular only, as a pronoun, e.g.:

Aucun de mes amis n’est venu

Not one of my friends came

Aucune de ces raisons n’est valable

None of these reasons is valid

De tous mes amis, aucun ne m’a aidé

Of all my friends, not one helped me

In compound tenses it follows the past participle, e.g.:

Je n’en ai acheté aucun

I did not buy one (any) of them

(ii) As a determiner, e.g.:

Aucun exemple ne me vient à l’esprit

No example comes to my mind

Je n’ai aucune intention d’y aller

I have no intention of going there

As a determiner, aucun is not used in the plural except sometimes with nouns that have no singular (e.g. aucuns frais ‘no expenditure’) or are used in the plural with a meaning they do not have in the singular (e.g. aucuns gages ‘no wages’).

547 nul ‘no, not any, etc.’

(i) Nul is characteristic of the literary rather than the spoken language.

(ii) As a pronoun it is used, usually only in the singular and only as the subject of the verb:

(a) with reference to some person or thing already mentioned (in which case the conversational equivalent is aucun), e.g.:

De toutes les maisons que je connais, nulle n’est plus agréable que la vôtre

Of all the houses I know, none is more pleasant than yours

(b) meaning ‘nobody’ (in this sense personne, not aucun, is used in speech), e.g.:

Nul ne sait ce qu’il est devenu

Nobody knows what has happened to him

(iii) As a determiner, nul is used in the literary language, mainly in the singular but occasionally (though this should not be imitated) in the plural, as the equivalent of aucun, e.g.:

Je n’ai nulle envie de la faire

I have no desire to do so

548 aucunement, nullement ‘not at all’

Aucunement and, especially in the literary language, nullement serve to negate the verb more emphatically than pas; they follow the verb (or the auxiliary, or the infinitive if the sense requires it), e.g.:

Je n’en suis aucunement (or nullement) froissé

I am in no way (or not at all) put out about it

Je ne crains nullement (or aucunement) la mort

I am not in the least afraid of death

Il semble ne vouloir aucunement y aller

He seems to be by no means anxious to go there

549 ne … guère ‘hardly, scarcely’

Ne … guère is used both as an adverb, e.g.:

Cela n’est guère probable

That is hardly likely

Je ne comprends guère ce qu’il dit

I scarcely understand what he says

and as a quantifier, e.g.:

| Je n’ai guère d’argent | I have hardly any money |

In compound tenses it precedes the past participle, e.g.:

Je ne l’aurais guère cru

I should hardly have believed it

550 ne … jamais ‘never’

Jamais usually follows the verb or the auxiliary, e.g.:

| Je ne bois jamais de vin | I never drink wine |

| Il n’a jamais dit ça | He never said that |

but it comes before the infinitive, e.g.:

Il décida de ne jamais revenir

He decided never to come back

For emphasis, it may be placed first, e.g.:

| Jamais je ne dirais ça! | I would never say that! |

551 ne … personne ‘nobody’, ne … rien ‘nothing’

Personne and rien can serve either as the subject or as the object of a verb or as the complement of a preposition, e.g.:

Personne n’arrivera ce soir

Nobody will arrive this evening

Rien ne le satisfait

Nothing satisfies him

Je ne vois personne

I can’t see anyone

Je ne dirai rien

I shall say nothing

Je ne travaillais avec personne

I wasn’t working with anybody

Je ne pensais à rien

I wasn’t thinking of anything

Note that, in compound tenses, rien follows the auxiliary but personne follows the past participle, e.g.:

Je n’ai rien vu

I saw nothing (I haven’t seen anything)

Je n’ai vu personne

I saw no one (I haven’t seen anyone)

Nous n’avions rien fait d’intéressant

We hadn’t done anything interesting

(Rien, however, sometimes follows the participle if it is qualified, e.g. Je n’ai trouvé rien qui vaille la peine ‘I found nothing worthwhile’.)

Likewise, rien goes before and personne after the infinitive, e.g.:

Il a décidé de ne rien faire

He decided to do nothing

Il a décidé de n’accepter personne

He decided to accept nobody

552 ne … plus ‘no longer, not any more’

Ne … plus means ‘no more’ only in the sense of ‘no longer, not any more’, e.g.:

Je n’y travaille plus

I don’t work there any more, I no longer work there

Nous n’avons plus de pain

We have no more bread (i.e. no bread left)

(‘No more’ in a strictly comparative or quantitative sense is ne … pas plus, e.g. Ce livre n’est pas plus intelligible que l’autre ‘This book is no more intelligible than the other one’, Je n’ai pas plus de temps que vous ‘I have no more time than you’.)

Plus follows the verb or auxiliary, but precedes the infinitive, e.g.:

Je n’y suis plus allé

I never went there any more

J’ai décidé de ne plus y aller

I have decided not to go there any more

553 ne … que … ‘only’

(i) Whereas in unaffected English (as distinct from pedantic English) ‘only’ can go before the verb even when it relates to something else, provided the meaning is clear from the context (e.g. ‘He only works on Saturdays’ = ‘He works only on Saturdays’), the que of ne … que … always goes immediately before the element it relates to, e.g.:

Je n’en ai que trois

I only have three

Il ne travaille que le samedi

He only works (= works only) on Saturdays

Je ne l’ai dit qu’à mon frère

I only told (told only) my brother

(ii) As que must also follow the verb, there might seem to be a problem when ‘only’ relates to the verb itself, as in ‘She only laughed’ or ‘On Saturdays he only works’ (i.e. ‘All he does on Saturdays is work’); what happens in French is that the verb faire ‘to do’ is used to express the relevant person, tense and mood, which que can then follow while at the same time preceding the infinitive of the verb it relates to, e.g.:

Je ne faisais que plaisanter

I was only joking

Elle n’a fait que rire

She only laughed

Le samedi il ne fait que travailler

On Saturdays he only works

All he does on Saturdays is work

Il ne fera que te gronder

He’ll only scold you

(iii) Though the use of ne … pas que … to mean ‘not only’ is frowned on by some purists, it is well established in literary as well as spoken usage and there is no good reason to avoid it, e.g.:

Ne pensez pas qu’à vous (A. France)

Don’t only think of yourself

Il ne négligea pas que l’église (Mauriac)

It was not only the church he neglected

Il n’y a pas que l’argent qui compte

It is not only money that counts (i.e. Money isn’t everything)

554 ‘Fossilized’ negative complements

In a few idioms, goutte and mot replace rien. Goutte occurs only with voir ‘to see’, comprendre ‘to understand’, and entendre in the sense of ‘to understand’ (not in the sense of ‘to hear’) and usually with y before the verb or, failing that, à + a noun, e.g.:

La lune est cachée, on n’y voit goutte (Mauriac)

The moon is hidden, one cannot see a thing

L’électeur moyen n’y comprend goutte (Le Monde)

The average voter understands nothing about it

Ils ne comprennent goutte à ma conduite (Flaubert)

They completely fail to understand my behaviour

Mot still retains its meaning of ‘word’ and occurs only with dire ‘to say’, répondre ‘to answer’ and in the idioms ne (pas) sonner mot and ne (pas) souffler mot ‘not to utter a word’, e.g.:

Le curé souriait … mais ne disait mot (Mauriac)

The priest smiled but said nothing

Il n’en souffle mot à personne (P.-J. Hélias)

He says nothing about it to anyone

555 Multiple negative complements

Pas and point cannot be combined with any of the other negative complements discussed in 546–554 (except in the expression ne … pas que, see 553,iii). Various combinations of other complements are, however, possible, e.g.:

Personne n’a rien dit

Nobody said anything

Personne ne peut plus le supporter

Nobody can stand him any more

Il n’a jamais blessé personne

He has never hurt anyone

Nous n’avons jamais eu aucun problème

We never had any problem

Cela ne me regarde plus guère

That hardly concerns me any more

Il se décida à ne jamais plus rien supporter de la sorte

He decided never to put up with anything of the kind again

556 In colloquial usage, ne is very frequently omitted and the negation is expressed by pas, rien, jamais, etc., alone, e.g.:

| Je veux pas y aller | I don’t want to go (there) |

| Dis pas ça! | Don’t say that! |

| J’ai rien acheté | I haven’t bought anything |

| Tu viens jamais me voir | You never come and see me |

This is so widespread, even in educated speech, that it cannot be considered unacceptable. However, foreigners should not adopt this construction until they can speak French fluently and correctly and at a normal conversational speed.

For more on this, see R. Ball, Colloquial French Grammar (Oxford, Blackwell, 2000), pp. 13–25.

The feature in question is sometimes found in print in plays, novels, etc., that aim to represent spoken usage; the following examples are from Sartre’s play Les Mains sales:

| C’est pas vrai | It isn’t true |

| Touche pas | Don’t touch |

| Je crois pas | I don’t think so |

It should not, however, be used in writing in other circumstances.

Negation without ne

557 pas without ne

When the verb of a negative clause is dropped, the ne of course drops with it and pas alone expresses the negation; for example, in answer to the question Est-il arrivé? ‘Has he arrived?’, instead of the complete sentence Il n’est pas encore arrivé ‘He has not yet arrived’, one is likely to find simply the expression Pas encore ‘Not yet’. This is a construction one constantly comes across. Further examples:

Est-ce que vous l’admirez? – Pas du tout (or even Du tout)

Do you admire him? – Not at ail

Tu viens? – Pas tout de suite

Are you coming? – Not immediately

Qu’est-ce que je dois prendre? Pas ça!

What am I to take? – Not that!

Qui l’a dit? – Pas moi, de toute façon

Who said so? – Not me, at any rate

Likewise certainement pas ‘certainly not’, pourquoi pas? ‘why not?’, pas là! ‘not there!’, etc.

For other negative complements without ne, see 558,iii.

558

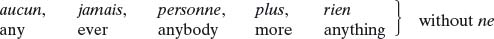

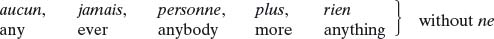

(i) As sans ‘without’ implies a negative, these five words may be used after sans or sans que ‘without’, e.g.:

sans aucune raison, sans raison aucune

without any reason

sans jamais le dire

without ever saying so

sans voir personne

without seeing anyone

sans plus tarder

without delaying any more, without further delay

sans rien dire

without saying anything, saying nothing

Il est parti sans rien

He left without anything

Elle est partie sans que personne le sache

She left without anyone knowing

sans que rien soit fait

without anything being done

(ii) The five words in question originally had a positive value and this survives in questions and comparisons and after si ‘if’, e.g.:

Y a-t-il aucune raison pour ça?

Is there any reason (at all) for that?

Je le respecte plus qu’aucun autre homme

I respect him more than any other man

Vous le savez mieux que personne

You know better than anyone

Avez-vous jamais rien entendu de si absurde?

Have you ever heard anything so absurd?

Si jamais vous le voyez, dites-le-moi

If ever you see him, tell me

On jamais, see also 618.

Plus retains a positive value generally, not just in the circumstances mentioned above – see 159–173.

(iii) As is explained in 557, pas retains a negative value when the verb (and hence the ne) of a negative clause is dropped. The same is true of aucun, jamais, personne, plus and rien. Each of these originally had a positive value but, through their constant association with negative constructions, they have themselves acquired a negative value in the circumstances in question, e.g.:

Y a-t-il aucune raison pour ça? – Aucune

Is there any reason for that? – None

Le lui avez-vous jamais montré? – Jamais

Have you ever shown it to him? – Never

Qui vous l’a dit? – Personne

Who told you so? – Nobody

Plus de discussions!

No more arguing!

Qu’est-ce qu’il t’a dit? – Rien de très intéressant

What did he tell you? – Nothing very interesting

Ne alone

559 In medieval French, ne was frequently used on its own (i.e. without pas or any other complement, though these were in fact already in use) to negate a verb, e.g. Ne m’oci! ‘Don’t kill me!’ There are relics of this in modern French, falling into three categories, viz.:

(i) Fixed expressions and proverbs (560)

(ii) Constructions in which ne is a literary alternative to ne … pas (561)

(iii) Constructions in which ne is superfluous (and where English has no negative at all) (562–567)

(i) Ne on its own in fixed expressions and proverbs

560 Ne is used on its own:

(a) In a number of fixed expressions, including:

A Dieu ne plaise!

God forbid!

N’ayez crainte!

Fear not! Never fear!

N’importe or Il n’importe

It doesn’t matter

Qu’à cela ne tienne!

Never mind that!

(b) A few constructions that can vary slightly in respect of their subject and/or tense and/or complement, and mainly involving one or other of the verbs avoir and être, e.g.:

n’avoir cure de

not to be concerned about

n’avoir (pas) de cesse que …

not to rest until …

n’avoir garde de (faire)

to take good care not to

n’avoir que faire de (+ noun)

to have no need of, no use for, to manage very well without

n’était

but for, were it not for

n’eût été

but for, had it not been for

si ce n’est (+ noun or pronoun)

if not …, apart from

Examples:

Il n’avait garde de contredire sa fille (Mérimée)

He took care not to contradict his daughter

Je n’ai que faire de ses conseils

I can manage very well without his advice

N’était son arrogance, il serait sûr de réussir

Were it not for his arrogance, he would certainly succeed

On ne voyait rien si ce n’est le ciel (Barbier d’Aurevilly)

Nothing was to be seen apart from the sky

Three such expressions involving other verbs are n’en déplaise à ‘with all due respect to’, n’empêche que ‘the fact remains that’, and savoir in the conditional, meaning ‘to be able’ (of the constructions listed here, these last two are the only ones that are current in conversational usage), e.g.:

N’empêche qu’il a tout à fait tort

The fact remains that he is quite wrong

Je ne saurais répondre à votre question

I can’t answer your question

(c) A few proverbs beginning with il n’est … ‘there is not’, e.g.:

Il n’est pire eau que l’eau qui dort

Still waters run deep (lit. There is no worse water than sleeping water)

Il n’est pire sourd que celui qui ne veut pas entendre

There is none so deaf as he who will not hear

(ii) Ne as a literary alternative to ne … pas

561 In a variety of constructions, the use of ne alone is still possible, particularly in the literary language. The principal constructions in question are:

(a) With the verbs cesser ‘to cease’ (but only when followed by de and an infinitive), daigner ‘to deign’, oser ‘to dare’, pouvoir ‘to be able’, and occasionally bouger ‘to move’, e.g.:

| Il ne cesse de pleurer | He never stops crying |

| Je n’ose l’avouer | I dare not admit it |

| Je ne peux vous aider | I cannot help you |

| Ne bougez d’ici! | Don’t move from here! |

(b) With savoir followed by an indirect question (in which case it is better to use ne alone rather than ne … pas), e.g.:

Je ne sais pourquoi

I don’t know why

Il ne sait quel parti prendre

He does not know what course to take

or in answer to a question:

Qu’allez-vous faire? – Je ne sais encore

What you going to do? – I don’t yet know

(c) In rhetorical or exclamatory questions introduced by qui? ‘who?’, quel? + noun ‘what?’, que? ‘what?’ or que? ‘why’, e.g.:

Qui ne court après la Fortune? (La Fontaine)

Who does not chase after Fortune?

Que ne dirait-on pour sauver sa peau?

What would a man not say to save his skin?

Que ne sommes-nous arrivés plus tôt!

Why did we not get here sooner! If only we had got here sooner!

(d) After si, especially when the main clause is negative, e.g.:

Je ne vous lâcherai pas si vous ne l’avouez

I will not let you go unless you confess

Le voilà qui arrive, si je ne me trompe

Here he comes, if I am not mistaken

(e) After non que, non pas que, ce n’est pas que ‘not that’, e.g.:

Non qu’il ne veuille vous aider …

Not that he does not want to help you

Ce n’est pas qu’il ne fasse des efforts, mais qu’il oublie tout

It is not that he doesn’t try, but that he forgets everything

(f) In relative clauses taking the subjunctive after a negative (expressed, or implied in a question) in the preceding clause, e.g.:

Il ne devrait être personne qui ne veuille apprendre le français

There ought to be no one who does not want to learn French

Y a-t-il personne qui ne veuille apprendre le français?

Is there any who …? etc. (= Surely there is no one who … etc.)

Il n’y a si bon cheval qui ne bronche

There is no horse so good that it never stumbles

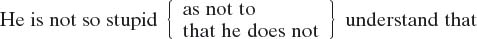

(g) In a que-clause expressing consequence after tellement or si meaning ‘so’, e.g.:

Il n’est pas tellement (or si) bête qu’il ne comprenne cela

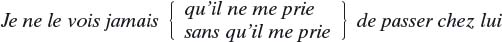

(h) In a dependent clause meaning ‘without … -ing’; que … ne in this sense is equivalent to sans que, e.g.:

I never see him without his asking me to drop in on him

(i) As an alternative to ne … pas in conditional sentences with inversion of the subject (see 424), e.g.:

Il se serait retiré, n’eût-il (pas) pensé qu’il se ferait remarquer

He would have withdrawn had he not thought he would attract attention

(j) For ne or ne … pas after depuis que, etc., see 567.

(iii) Ne inserted where English has no negative

562 Ne alone occurs in a number of constructions that are not, strictly speaking, negative though, as we shall see, there is usually a negative implication of some kind or other. This ne is often referred to as ‘redundant ne’, ‘pleonastic ne’ or ‘expletive ne’. In speech the ne is dropped more often than not and it is also often dropped in writing in an informal style.

The constructions in question can be classified as follows:

(a) after comparatives (563)

(b) after verbs and expressions of fearing (564)

(c) after certain other verbs and their equivalents (565)

(d) after the conjunctions avant que ‘before’ and à moins que ‘unless’ (566)

(e) after the conjunction depuis que ‘since’ and comparable expressions (567).

563 (a) Ne after comparatives

In an affirmative clause after a comparative and que ‘than’, e.g. Il en sait plus qu’il n’avoue ‘He knows more than he admits’, the use of ne can be explained by the fact that the que-clause contains a negative implication, viz. ‘He does not admit to knowing as much as he does’. Other examples:

Il a agi avec plus d’imprudence que je ne croyais

He has acted more rashly than I thought

Il est moins riche qu’il ne l’était

He is less rich than he was

Also with autre(ment) que ‘other than, otherwise than’, e.g.:

Il agit autrement qu’il ne parle

He acts differently from the way he speaks

Note, however, that, when the main clause is interrogative or negative, the ne is not usually used unless the negative of the first clause also covers the second clause, e.g.:

Avez-vous jamais été plus heureux que vous l’êtes maintenant?

Have you ever been happier than you are now?

Jamais homme n’était plus embarrassé que je le suis en ce moment

Never was a man more embarrassed than I am at this moment

Vous ne réussirez pas mieux que nous n’avons réussi nousmêmes

You will not succeed any better than we have

(i.e. ‘We have not succeeded and you will not succeed’)

(Ne is sometimes used after questions, particularly when the question is rhetorical, e.g.:

Peut-on être plus bête qu’il ne l’est?

Can anyone be stupider than he is?)

564 (b) Ne after verbs and expressions of fearing

The use of ne after verbs and expressions of fearing such as craindre que ‘to fear that’, avoir peur que ‘to be afraid that’, de crainte que, de peur que ‘for fear that’, is explained by the fact that a fear that something may happen implies a hope or wish that it may not happen; for example, J’ai peur que ce ne soit vrai ‘I am afraid it may be true’, and Il est parti de peur qu’elle ne le voie ‘He left for fear she might see him’, imply respectively a hope that it might not be true and that she should not see him.

Note that after a verb of fearing that is itself negative there is no ne and that the problem does not, of course, arise when the verb of the que-clause is itself negative. We therefore have the following constructions:

Je crains qu’il ne vienne

I am afraid he will come

Je ne crains pas qu’il vienne

I am not afraid he will come

Je crains qu’il ne vienne pas

I am afraid he will not come

Je ne crains pas qu’il ne vienne pas

I am not afraid he will not come

565 (c) Ne after other verbs and their equivalents

After douter ‘to doubt’ when negative or interrogative, e.g.:

Je ne doute pas qu’il ne vienne

I have no doubt he will come

Doutez-vous qu’il ne vienne?

Do you doubt whether he will come?

but, after douter in the affirmative:

| Je doute qu’il vienne | I doubt if he will come |

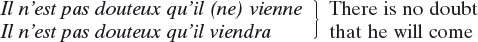

Il n’est pas douteux que … takes either the subjunctive with or without ne or the indicative without ne, e.g.:

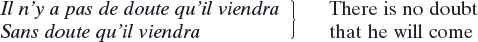

Other negative expressions of doubt are usually followed by the indicative without ne, e.g.:

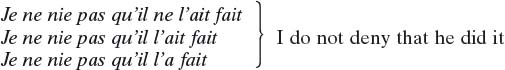

Nier ‘to deny’ when affirmative follows the same rule as douter; but, when negative, it can have any of the constructions illustrated below:

| Je nie qu’il l’ait fait | I deny that he did it |

After nier in the interrogative, the verb of the que-clause is usually in the subjunctive, with or without ne, e.g.:

Niez-vous qu’il (ne) l’ait fait?

Do you deny that he did it?

Note that, if the person is unchanged, the infinitive can be used, e.g.:

Il ne nie pas l’avoir fait

He does not deny doing it (that he did it)

Empêcher que ‘to prevent’ and éviter que ‘to avoid’ are usually but not invariably followed by ne whether they are used affirmatively or negatively, e.g.:

Rien n’empêche qu’on (ne) fasse la paix

Nothing prevents peace from being made

J’évite qu’il (ne) m’en parle

I avoid having him speak to me about it

But note that empêcher is very frequently followed by an infinitive, e.g. Il m’empêche de partir ‘He prevents me from leaving’.

Ne is optional after peu s’en faut que or il s’en faut que (for which no even approximately literal translation is possible), e.g.:

Peu s’en fallut qu’il (ne) tombât dans la mer

He very nearly fell into the sea

Il s’en faut de beaucoup que cette somme soit suffisante

This sum is far from being enough

A few moments’ thought ought to be enough to identify the negative implication in the above examples – for example, ‘to prevent something from happening’ is ‘to ensure that it does not happen’.

566 (d) Ne after avant que ‘before’ and à moins que ‘unless’

The use of ne after avant que ‘before’ and à moins que ‘unless’ is optional, but it is in general preferred in modern literary usage (much more so than in Classical French), e.g.:

Je le verrai avant qu’il (ne) parte

I shall see him before he leaves

Avant qu’ils n’eussent atteint la galerie … (J. Green)

Before they had reached the gallery …

Il va y renoncer à moins que vous (ne) l’aidiez

He is going to give up unless you help him

The negative implication of such examples as these is clear – ‘he has not yet left’, ‘they had not reached the gallery’, ‘if you do not help him’.

Note that the use of ne after sans que ‘without’ that one sometimes comes across is best avoided, e.g.:

Il est parti sans que ses parents le sachent

He left without his parents knowing about it

567 (e) Depuis que and comparable expressions

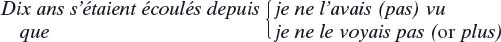

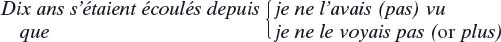

The two interlocking problems that arise with the use of depuis que, viz. that of the choice of tense and that of the choice between ne and ne … pas, can best be explained if we first take an example. ‘Ten years have passed since I saw him’ (a sentence in which, in

English, there is no negative) may be translated either by:

Dix ans se sont écoulés depuis que je ne l’ai vu

(i.e. with the perfect tense and ne), or by:

Dix ans se sont écoulés depuis que je ne le vois pas (or plus)

(i.e. with the present tense and either ne … pas or ne … plus). The sense of the second of these forms becomes plain if one takes depuis que as an equivalent of ‘during which’, i.e. ‘Ten years have passed during which I do not (or I no longer) see him’.

Furthermore, the first type has influenced the second and so one often comes across the construction:

Dix ans se sont écoulés depuis que je ne l’ai pas vu

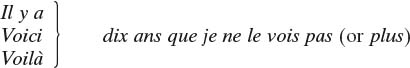

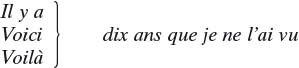

Alternative constructions to depuis que are provided by il y a, voici, voilà + expression of a period of time (e.g. dix ans ‘ten years’, longtemps ‘a long time’) + que, e.g.:

It is ten years since I saw him

or, alternatively:

Another alternative construction is provided by cela (ça) fait, e.g. Ça fait dix ans que je ne l’ai pas vu. But note that since cela (ça) fait is a somewhat informal construction and the use of ne alone is a literary construction, the two should not be combined, i.e. with cela fait or ça fait always use ne … pas.

Similarly with reference to the past:

Ten years had elapsed since I saw (or had seen) him

It was ten years since I had seen him

Note that the use of pas or plus is optional with the compound tenses (i.e. the perfect and the pluperfect) but compulsory with the simple tenses (the present and the imperfect). Generally speaking, plus is more widely used than pas with the simple tenses.

De, du, etc., un(e) and the direct object of negative verbs

568 De is normally substituted for the partitive or the indefinite article with the direct object of a verb in the negative (for exceptions, see 569 and 570), e.g.:

Nous avons une maison

We have a house

Nous n’avons pas de maison

We haven’t a house

Ils vendent du fromage

They sell cheese

Ils ne vendent pas de fromage

They don’t sell cheese

Nous avons eu de la difficulté

We have had some difficulty

Nous n’avons jamais eu de difficulté

We have never had any difficulty

Note that, in the construction il y a ‘there is, there are’ followed by a noun (e.g. Il y a des pommes ‘There are (some) apples’), the noun is the direct object of the verb a (from avoir) and so the rule applies (e.g. Il n’y a pas de pommes ‘There aren’t any apples’).

Note too that ne … que ‘only’ is not negative in sense and so does not follow the rule, e.g. Il n’y a que des pommes ‘There are only apples’.

569 The use of the indefinite article, un, une, is not impossible after a negative, but there is a difference in meaning between this construction and the usual construction with pas de discussed in 568. Whereas pas de expresses the negation in an unemphatic way (‘not a’), pas un is somewhat emphatic (‘not one, not a single’), e.g.:

Il n’y a pas de communiste qui soit capitaliste

There is no communist who is a capitalist

Il n’y a pas un communiste qui soit capitaliste

There is not a single communist who is a capitalist

Je ne vois pas de cheval

I can’t see a horse

Je ne vois pas un cheval

I can’t see a single horse

(This last sentence might be spoken to express one’s disappointment, for example, at not seeing any horses in circumstances where one had been expecting to see some.) Some circumstances virtually exclude the construction with pas un: for example, one might very well say of a woman Elle n’a pas de mari ‘She hasn’t got a husband’, but it is difficult to imagine any kind of normal context in which one could say, as a complete sentence, Elle n’a pas un mari.

Similarly in negative questions. Whereas N’avez-vous pas de crayon? merely means ‘Haven’t you got a pencil?’, to ask N’avez-vous pas un crayon? has something of the same implication as ‘You haven’t (by any chance) a pencil, have you?’ (i.e., if so, may I borrow it?).

570 The construction discussed in 568 must be clearly distinguished from others that are superficially similar (or even, in English – but not in French – identical), but have a very different meaning.

One of these is the construction in which the negation applies, according to the sense, not to the verb but to the direct object. For example, ‘I didn’t buy a car’ may carry the implication, or be followed by a specific statement, that ‘I bought something else (e.g. a bike)’. So, in French we have Je n’ai pas acheté une voiture (mais un vélo). The meaning in effect is ‘I bought not a car but a bike’, i.e. the negation, according to the sense, applies not to the verb ‘bought’ but to the direct object ‘car’.

Another similar construction is that in which the negation applies, according to the sense, neither to the verb nor to the direct object but to some other element in the sentence. For example, an utterance such as ‘One doesn’t keep a dog in order to eat it’ has the implication ‘If one keeps a dog, it is not in order to eat it’. So, in French one has On n’a pas un chien pour le manger.

571 Ni is the equivalent both of ‘neither’ and of ‘nor’. There are important differences between the two languages in the use of these conjunctions:

(i) When they apply to finite verbs (see 341), ‘neither’ is ne and ‘nor’ is ni ne (and note that both negative elements are essential here – ni alone will not do), e.g.:

Je ne peux ni ne veux y consentir

I neither can nor will agree to it

Il ne m’écrit ni ne vient me voir

He neither writes to me nor comes to see me

(ii) When they apply to elements other than a finite verb, each of the elements in question (which may be, for example, the subject, the direct or indirect object, past participles, infinitives, adjectives, adverbs, prepositional phrases, etc.) is preceded by ni while the finite verb is preceded by ne, e.g.:

Ni lui ni moi ne serons prêts à temps

Neither he nor I will be ready in time

Il ne comprend ni l’anglais ni le français

He understands neither English nor French

Je ne le donne ni à Pierre ni à Jean

I am giving it neither to Peter nor to John

Je ne les ai ni vus ni entendus

I have neither seen nor heard them

Il ne veut ni m’écrire ni me téléphoner

He will neither write to me nor telephone me

Je ne suis ni riche ni avare

I am neither rich nor miserly

Il ne vient ni aujourd’hui ni demain

He is coming neither today nor tomorrow

Nous n’allons ni à Paris ni à Strasbourg

We are going neither to Paris nor to Strasburg

(iii) the construction (ne) … ni … ni is also the equivalent of ‘not … or … (either)’, ‘Not … either … or’, etc.; for example, the second, third, fourth and last examples in ii above could also be translated ‘He doesn’t understand (either) English or French’, ‘I am not giving it either to Peter or to John’, ‘I haven’t seen them or heard them’, ‘We are not going to Paris or to Strasburg either’, and similar alternative translations could be provided for the other examples except the first (in which ‘neither … nor’ relate to the subject of the verb).

(iv) French uses ni where English uses ‘and’ or ‘or’ after a negative or after sans or sans que ‘without’, e.g.:

sans père ni mère

without father or mother, with neither father nor mother

Il faut le faire sans qu’il voie ni (qu’il) entende rien

It must be done without his seeing or hearing anything

La vieille aristocratie française n’a rien appris ni rien oublié

The old French aristocracy has learnt nothing and forgotten nothing

(v) Note the use of ni to introduce a kind of afterthought after a negative construction with ne … pas, e.g.:

Il ne faut pas s’asseoir ni même se remuer avant que la reine n’ait donné le signe

No one must sit down or even move till the queen gives the signal

Il ne comprend pas le français, ni l’anglais d’ailleurs

He doesn’t understand French, or indeed English

When the newly introduced element is the equivalent of the subject, English has the construction ‘neither (or nor)’ + some such verb as ‘is, has does, shall, will, can, must’ + the subject; French has the construction ni (optional – see below) + subject (disjunctive form if it is a personal pronoun) + non plus, e.g.:

Il n’y va pas, (ni) son frère non plus

He is not going (and) neither is his brother

Je ne regarde jamais la télé, (ni) ma femme non plus

I never watch TV, (and) neither (or nor) does my wife

(Ni) moi non plus

Neither am I (have I, can I, do I, etc.)

Elle ne travaillait jamais. – (Ni) lui non plus

She never worked. – Neither did he

In speech, the form without ni is the more usual, the form with ni being rather more emphatic.

572 ‘No’ or ‘not’ as the equivalent of a negative sentence.

The English ‘no’ in answer to a question, or by way of being a comment, an objection, a warning, etc., is translated by non or, more emphatically, by mais non!, e.g.:

Vous partez demain? – Non, monsieur

Are you leaving tomorrow? – No, sir

Non! non! non! Ce n’est pas comme ça qu’il faut le faire!

No! no! That’s not the way to do it!

Vous partez demain, n’est-ce pas? – Mais non! Je reste encore trois jours

You’re leaving tomorrow, aren’t you? – No! I’m staying another three days

573 As an exclamatory negative (usually with a sense of protest against the suggestion made), que non is sometimes used, e.g.:

A votre avis, votre mari est-il coupable? Oui, ou non? – Que non! Oh, que non!

In your opinion, is your husband guilty? Yes, or no? – No! Oh, no!

574 After verbs of saying or thinking and a few others such as espérer ‘to hope’, and after certain adverbs of affirmation or doubt (see 627–628) such as heureusement ‘fortunately’ and peut-être ‘perhaps’, ‘not’ or ‘no’ can take the place of an object clause; e.g. ‘I hope not’ as an answer to ‘Is he coming?’ is the equivalent of ‘I hope he is not coming’ (it is not therefore the equivalent of ‘I do not hope’). The French equivalent of this, and also of ‘not … so’ in such sentences as ‘I don’t think so’, is que non, e.g.:

Il part déjà? – J’espère que non / Je crois que non

Is he leaving already? – I hope not / I don’t think so

Tu viens à la piscine? – J’ai déjà dit que non

Are you coming to the swimming pool? – I’ve already said no (or … said I’m not)

Vous feriez mieux de ne pas lui écrire. – Peut-être que non.

You had better not write to him. – Perhaps not.

(For a similar use of que oui and que si, see 628,ii.)

Non, non pas, pas ‘not’

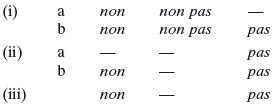

575 When ‘not’ negates some element other than the verb, there are three possible forms, viz. non, non pas, or pas. These are interchangeable in some circumstances but not, unfortunately, in all circumstances. We have to distinguish between a number of different constructions. The following summary is based on the admirably clear explanation given by R.-L. Wagner and J. Pinchon in their Grammaire du français classique et moderne, revised edition, Paris, Hachette, 1991, pp. 433–4.

All depends on whether (i) two items are presented as being in opposition to one another, or (ii) two elements are presented as being alternatives, or (iii) only one item is expressed (and, of course, in the negative). Further distinctions are necessary in (i) according to whether it is the first or the second element that is negatived, and in (ii) according to whether or not the second element is or is not expressed. These distinctions should become clear from the examples that follow.

576 (i) Two elements are presented as being in opposition (i.e. we have one or other of the constructions ‘not X but Y’ or ‘X not Y’):

(a) The first element is negatived – ‘not’ is non or non pas, e.g.:

Il a l’air non fatigué mais malade

Il a l’air non pas fatigué mais malade

He looks not tired but ill

Elle arrive non mardi mais jeudi

Elle arrive non pas mardi mais jeudi

She is arriving not on Tuesday but on Thursday

Henri sera mon cavalier, non (pas) qu’il soit beau, mais parce qu’il danse à ravir

Henry shall be my partner, not that he is handsome, but because he dances divinely

(b) The second element is negatived – ‘not’ is non, non pas, or pas:

Il a l’air fatigué, non malade

Il a l’air fatigué, non pas malade

Il a l’air fatigué, pas malade

He looks tired, not ill

Elle arrive mardi, non jeudi

Elle arrive mardi, non pas jeudi

Elle arrive mardi, pas jeudi

She is arriving on Tuesday, not on Thursday

Il l’a fait par mégarde, non (non pas, pas) avec intention

He did it by mistake, not on purpose

577 (ii) Two elements are presented as being alternatives (i.e. we have one or other of the constructions ‘X or not X’ or ‘X or not’):

(a) The second element is expressed – ‘not’ is usually pas, e.g.:

Fatigué ou pas fatigué, il part demain

Tired or not tired, he is leaving tomorrow

Qu’il parle bien ou pas bien, peu importe

Whether he speaks well or not well, it doesn’t much matter

(b) The second element is not expressed – ‘not’ is non or pas, e.g.:

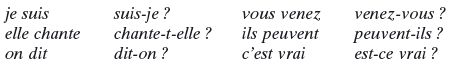

Fatigué ou non, il part demain

Fatigué ou pas, il part demain

Tired or not, he is leaving tomorrow

Qu’il parle bien ou non, peu importe

Qu’il parle bien ou pas, peu importe

Whether he speaks well or not, it doesn’t much matter

Les uns l’aiment, les autres non

Les uns l’aiment, les autres pas

Some like it, others not

578 (iii) Only one (negative) item is expressed – not is non or pas, e.g.:

Il habite non loin de Paris

Il habite pas loin de Paris

He lives not far from Paris

Il était furieux et non content de ce qu’il avait vu

Il était furieux et pas content de ce qu’il avait vu

He was angry and not pleased with what he had seen

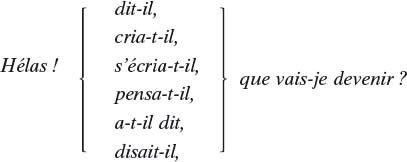

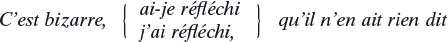

579 We therefore have the following pattern:

Note in particular:

(a) that non pas is used only to express opposition;

(b) that pas may be used in all constructions except to negative the first of two elements in opposition.

Note also that, where there is a choice between non and pas, the former is characteristic of a more formal, the latter of a more familiar style.

580 Non is used before a past participle not compounded with être or avoir, e.g.:

| une leçon non sue | a lesson not known |

| vin non compris | wine not included |

| les pays non-alignés | the non-aligned countries |

before a present participle used purely as a noun or qualifying adjective, e.g.:

| un non-combattant | a non-combatant |

and to form compounds (many of them technical) with various nouns and adjectives, e.g.:

non-conducteur

non-conductor

le point de non-retour

the point of no return

non-réussite

failure

non valable

invalid (excuse, etc.), not valid (ticket, etc.)

une manifestation non-violente

a non-violent demonstration

581 There are various ways of asking questions in French, and, in choosing which construction to use in a given context, it is essential to take account of medium and register (see 13). In general, it is important to note that the use of inversion (i.e., the placing of the subject after the verb, as in Vient-il? ‘Is he coming?’, Où allez-vous? ‘Where are you going?’) is relatively little used in informal registers. Note in particular the use of intonation alone to express a question (586), the tendency in informal registers to place the interrogative word (e.g. où? ‘where?’, pourquoi? ‘why?’) at the end rather than at the beginning of an utterance (593,i), and other constructions characteristic of highly informal registers (593,ii, iii).

Questions are either:

(i) Direct – e.g. ‘Are you coming?’, ‘What is he doing?’, ‘Why did the cat eat the goldfish?’

or (ii) Indirect – e.g. ‘(He asked) if I was coming’, ‘(I wonder) what he is doing’, ‘(Nobody knows) why the cat ate the goldfish’.

Direct questions fall into one or other of two categories:

(i) Total interrogation – i.e. ‘yes–no’ questions, e.g. ‘Is she happy?’, ‘Have you any change?’, ‘Did the cat eat the goldfish?’;

(ii) Partial interrogation – i.e. questions introduced by an interrogative expression, e.g. ‘Who?’, ‘What?’, ‘When?’, ‘Where?’, ‘How?’, ‘Why?’, ‘How many?’, ‘Which book?’, ‘For what reason?’

We shall discuss interrogative sentences under the following headings:

A: Direct questions: total interrogation

B: Direct questions: partial interrogation

C: Indirect questions

582 In direct questions, in either total or partial interrogation, English makes much use of the verb ‘do’, which has no function other than to turn a statement into a question, e.g.:

| I saw him | Did I see him? |

| My brother smokes too much | Does my brother smoke too much? |

| She bought a book | What did she buy? |

| They eat too much | Why do they eat too much? |

Note that, in French, the verb faire ‘to do’ is never used in this way.

583 The basic interrogative form of a ‘yes–no’ question when the subject is a personal pronoun or one or other of the pronouns on or (with être only) ce is obtained by inverting the subject, i.e. placing it after the verb, e.g.:

For the interrogative conjugation of a typical verb, see 387.

For the use of -t- when a verb form ending in a vowel is followed by il, elle or on, see 388.

Note that, in the present tense, the inversion of je is not possible with most verbs (see 389). Further examples:

Puis-je vous aider?

May I help you?

A-t-il terminé son travail?

Has he finished his work?

Viendra-t-elle nous voir?

Will she come and see us?

Aviez-vous beaucoup de voisins?

Did you have many neighbours?

584 A noun subject cannot be inverted in total interrogation. The equivalent construction is obtained by leaving the noun subject at the beginning and inverting the appropriate personal pronoun, e.g.:

Le chat a-t-il mangé le poisson rouge?

Has the cat eaten the goldfish?

Marie habitait-elle à Paris?

Did Mary live in Paris?

Les Français boivent-ils trop de vin?

Do the French drink too much wine?

Vos sœurs seront-elles contentes?

Will your sisters be pleased?

585 An alternative and widely used way of asking questions is to preface the affirmative form with Est-ce que …? (literally ‘Is it that …’? – but it must not be translated thus), e.g.:

Est-ce qu’elle viendra nous voir?

Will she come and see us?

Est-ce que Marie habitait à Paris?

Did Mary live in Paris?

This is an effective way of coping with those contexts in which je cannot be inverted, e.g.:

Est-ce que je parle trop?

Do I talk too much?

Est-ce que je pars tout de suite?

Do I leave immediately?

Note that est-ce que is often used for the sake of emphasis, expressing indignation, surprise or doubt, e.g.:

Est-ce que je vais me confier à de telles gens?

Do you think I am going to entrust myself to such people?

586 The excessive use of est-ce que should be avoided. In writing, this can be done by using inversion (see 583–584). In speech, questions are very frequently formed by means of intonation alone, keeping the same word-order as in statements, e.g.:

| Je parle trop? | Am I talking too much? |

| Tu pars déjà? | Are you leaving already? |

| Mon père est sorti? | Has my father gone out? |

587 The only French equivalent for English tag-questions, i.e. brief questions such as ‘Don’t I?’, ‘Isn’t she?’, ‘Haven’t you?’, ‘Won’t they?’, tacked on to an affirmative sentence, is n’est-ce pas?, e.g.:

Elle est très heureuse, n’est-ce pas?

She’s very happy, isn’t she?

Vous êtes allé à Paris, n’est-ce pas?

You’ve been to Paris, haven’t you?

Ils voyageaient beaucoup, n’est-ce pas?

They used to travel a lot, didn’t they?

Vous me prêterez votre voiture, n’est-ce pas?

You’ll lend me your car, won’t you?

N’est-ce pas? can also be used after a negative, as the equivalent of ‘Is she?’, ‘Did they?’, etc., e.g.:

Tu ne pars pas maintenant, n’est-ce pas?

You’re not leaving now, are you?

Il n’a jamais dit ça, n’est-ce pas?

He never said that, did he?

588 For questions involving the interrogative pronouns qui? ‘who?’, qu’est-ce qui?, qu’est-ce que?, que?, quoi? ‘what’, lequel? ‘which?’, see 280–290.

For questions introduced by combien? ‘how much?’, ‘how many?’, see 326.

589 In questions introduced by one of the interrogative adverbs où? ‘where?’ (or d’où?, jusqu’où?, par où?), quand? ‘when?’, comment? ‘how?’, pourquoi? ‘why?’, or an interrogative phrase including quel? ‘which?’, the subject, if a personal pronoun, on or (with the verb être only) ce, is inverted, as in total interrogation, e.g.:

Où avez-vous garé la voiture?

Where have you parked the car?

Quand viendra-t-elle nous voir?

When will she come to see us?

Pourquoi dit-on cela?

Why do they say that?

Comment le savaient-ils?

How did they know?

Pour quelle compagnie travaille-t-il?

Which company does he work for?

Où est-ce?

Where is it?

As in total interrogation, est-ce que? may be used, in which case the order subject–verb remains, e.g. (as alternatives to the above):

Où est-ce que vous avez garé la voiture?

Quand est-ce qu’elle viendra nous voir?

Pour quelle compagnie est-ce qu’il travaille? etc.

590 When the subject of a question introduced by où?, quand?, comment?, pourquoi?, a preposition + qui? or quoi?, or an expression including quel?, is a noun (or a pronoun other than a personal pronoun, on or ce), it may (contrary to what is the case in total interrogation, see 584) be inverted, subject however to certain restrictions (see 591–592), e.g.:

Où travaillait votre père?

Where did your father work?

Quand arrivent les enfants?

When are the children coming?

D’où est venue cette idée?

Where has that idea come from?

Avec qui voyage votre frère?

Who is your brother travelling with?

A quelle heure est la conférence?

What time is the lecture?

An alternative is to invert the appropriate subject pronoun, in which case the noun subject may go either before or after the interrogative word, e.g.:

Votre père où travaillait-il?

Où votre père travaillait-il?

Again, in speech in particular, est-ce que? provides a further alternative, e.g.:

Où est-ce que votre père travaillait?

Quand est-ce que les enfants arrivent?

591 The inversion of the noun subject is not possible with pourquoi and tends to be avoided with other interrogative words and phrases of more than one syllable. In such cases, one or other of the constructions referred to in 590 should be used, e.g.:

Pourquoi les enfants pleuraient-ils?

Why were the children crying?

Comment est-ce que votre frère le sait?

How does your brother know?

Combien votre sæur a-t-elle perdu?

How much has your sister lost?

592 The noun subject cannot be inverted when the verb has a direct object (other than a conjunctive pronoun) or some other complement to which it is closely linked and from which it should not be separated; an alternative construction must therefore be used, e.g.:

Où est-ce que votre frère gare sa voiture?

Where does your brother park his car?

Quand les étudiants passent-ils leurs examens?

When do the students sit their exams?

Quand les enfants partaient-ils en vacances?

When were the children leaving on holiday?

593 (i) A non-literary construction that is very current in speech is to put the interrogative word not first but after the verb (and, in most cases, at the end), e.g.:

| Vous allez où? | Where are you going? |

| Henri est arrivé quand? | When did Henry arrive? |

| Ton frère part quel jour? | What day is your brother leaving? |

| Vous en voulez combien? | How much (How many) do you want? |

| Il a fait ça pourquoi? | Why did he do that? |

| Elle écrit à qui? | Who(m) did she write to? |

| Il est où ton sac? | Where’s your bag? |

| C’est quand ton examen? | When is your exam? |

(On the use of both noun and pronoun subjects in the last two examples, see 602.)

(ii) A construction that occurs widely in informal spoken French, especially when the subject is a conjunctive personal pronoun (see 193–198), or on, ce, or ça, is that in which the interrogative word or phrase remains at the beginning (contrast i above) but the subject is not inverted, i.e. it remains before the verb (contrast 589), e.g.:

| Où vous avez trouvé ça? | Where did you find that? |

| Pourquoi tu (ne) veux pas venir? | Why don’t you want to come? |

| A quelle heure il est parti? | What time did he leave? |

| Combien ça coûte? | How much does it cost? |

| Quel âge il a? | How old is he? |

This construction occurs in the informal speech even of educated speakers and there is no good reason why it should not be copied, in informal speech, by foreigners whose conversational French is generally fluent and correct at a normal speed. It is particularly common with comment? ‘how?’, e.g. Comment tu t’appelles? ‘What is your name?’, Comment vous avez trouvé ce vin? ‘How did you find (i.e. What did you think of) this wine?’, and is firmly established in the expression Comment ça va? ‘How are things?’

(iii) Yet another construction but, in this case, one which is generally regarded as substandard and which should therefore be avoided by foreigners, even in informal speech, is that in which the interrogative word or phrase is followed by que, e.g.:

| Combien que je vous dois? | How much do I owe you? |

| Pourquoi que tu dis ça? | Why do you say that? |

| Avec quoi qu’il écrit? | What is he writing with? |

For more on questions in colloquial usage, see R. Ball, Colloquial French Grammar (Oxford, Blackwell, 2000), pp. 26–40.

594 Indirect questions corresponding to total interrogation are introduced by si ‘if, whether’, and take the appropriate tense as in English, e.g. (corresponding to Pouvez-vous m’aider? ‘Can you help me?’, Est-ce que le train arrivera à temps? ‘Will the train arrive in time?’, Est-ce qu’il viendra? ‘Will he come?’):

Il m’a demandé si je pouvais l’aider

He asked me if I could help him

Nous ne savions pas si le train arriverait à temps

We didn’t know whether the train would arrive in time

Je me demande s’il viendra

I wonder if (whether) he will come

Je me demandais s’il viendrait

I wondered if (whether) he could come

Note the use of this type of si-clause with ellipsis of the main clause where English would use an echo-question (i.e. a repeat question by way of seeking confirmation of the tenor of the original question – cf. 595), e.g.:

– M’aimes-tu? – Si je t’aime? (Balzac)

‘Do you love me?’ – ‘Do I love you?’ (i.e. ‘Are you asking me if I love you?’)

This sometimes has an exclamatory value, e.g.:

– Voulez-vous y aller? – Si je le veux!

‘Do you want to go?’ – ‘Do I want to!’ (= ‘I should think I do!’)

595 Indirect questions introduced by one of the interrogative expressions discussed in 588–589 have the same word-order as in affirmative clauses, e.g.:

Nous ne savions pas pourquoi il était parti

We didn’t know why he had left

Il m’a demandé à quelle heure le train partait

He asked me what time the train left

Je me demande où mon frère va acheter sa nouvelle voiture

I wonder where my brother is going to buy his new car

However, inversion of the noun subject is possible provided the indirect question is not introduced by pourquoi and there is no direct object and no other complement closely linked to the verb, e.g.:

Dites-moi où habite votre frère

Tell me where your brother lives

Je ne comprends pas comment vivaient les hommes des cavernes

I don’t understand how cavemen lived

Note the use of an indirect question with ellipsis of the main clause where English uses an echo-question (cf. 594), e.g.:

– Pourquoi es-tu venu? – Pourquoi je suis venu? (Loti)

‘Why have you come?’ – ‘Why have I come?’

– Où êtes-vous? – Où je suis? Mais je suis chez moi

‘Where are you?’ – ‘Where am I? I am at home’

These correspond to something like ‘You ask why I have come?’ and ‘You ask where I am?’

596 In most contexts, the subject in French precedes its verb, e.g. Il chante ‘He sings’, Mon frère habite ici ‘My brother lives here’, and this can therefore be considered the normal word-order in French. In certain circumstances, however, the subject follows the verb: this is known as ‘inversion’.

There are in fact three types of inversion in French:

(i) the pronoun subject follows the verb, e.g.:

Est-il arrivé? Peut-être viendra-t-il demain

Has he arrived? Perhaps he will come tomorrow

(ii) the noun subject follows the verb, e.g.:

C’est là qu’habite mon frère

That is where my brother lives

Non, monsieur, répondit le garçon

‘No, sir,’ the boy replied

(iii) A noun subject comes first and the corresponding conjunctive pronoun is added after the verb, e.g.:

Peut-être ma mère avait-elle changé d’avis

Perhaps my mother had changed her mind

Vos enfants sont-ils en vacances?

Are your children on holiday?

Types (i) and (ii) are sometimes known as ‘simple inversion’ and type (iii) as ‘complex inversion’.

597 For inversion:

in direct questions, see 583–584 and 589–592

with the subjunctive, expressing wishes, see 476–477

in hypothetical constructions, in the sense of ‘(even) if, supposing, etc.’, see 478.

598 (i) Inversion may occur when the subject is a noun (for exceptions, see ii, below) in indirect questions, relative clauses, and other subordinate clauses, e.g.:

Je ne comprends pas ce que dit mon professeur (or ce que mon professeur dit)

I don’t understand what my professor says

Savez-vous de quoi se fâchait son père? (or de quoi son père se fâchait?)

Do you know what his father was getting angry about?

Je ne connais pas le monsieur dont parlait mon père (or dont mon père parlait)

I don’t know the man my father was talking about

Voici le livre qu’a acheté mon frère (or que mon frère a acheté)

Here is the book my brother bought

Elle avait été heureuse tant qu’avait vécu son époux (or tant que son époux avait vécu)

She had been happy for as long as her husband had lived

(ii) Inversion of the noun subject is not, however, possible in such clauses if this would have the effect of separating the verb from some element with which it is closely linked, such as a direct object, e.g.:

Voici la librairie où mon frère achète ses livres

Here is the bookshop where my brother buys his books

or the complement of être or another linking verb (see 518), e.g.:

C’est en 1959 que de Gaulle est devenu Président de la République

It was in 1959 that de Gaulle became President of the Republic

or an adverbial complement modifying the verb, e.g.:

… tant que son époux avait travaillé à Paris

… for as long as her husband had worked in Paris

(iii) Inversion is not possible in such clauses when the subject is a conjunctive personal pronoun, or on or ce, e.g.:

Je ne peux pas deviner ce qu’il veut faire ici

I cannot imagine what he wants here

Je ne connais pas les hommes dont il parlait

I do not know the men of whom he was speaking

… tant qu’il avait vécu

… for as long as he had lived

(iv) It goes without saying that inversion is impossible when qui or ce qui is itself the subject.

599 In short parenthetical expressions reporting someone’s words, inversion is essential. This applies not only to verbs explicitly referring to speech, such as dire ‘to say’, s’écrier ‘to exclaim’, demander ‘to ask’, continuer ‘to continue (speaking)’, répondre ‘to reply’, but also to a few verbs such as penser ‘to think’, se demander ‘to wonder’ when they imply that the subject is inwardly addressing herself or himself, e.g.:

Je ne sais pas, répondit mon frère

‘I don’t know,’ my brother answered

‘Alas!’ he said (he shouted, he exclaimed, he thought, he said), ‘what will become of me?’

With other verbs that occasionally have a similar value, inversion is optional, e.g.:

It is odd, I reflected, that he has not mentioned it

600 Certain adverbs and adverbial expressions cause inversion more or less regularly (though not invariably) when they stand first in the clause. In the case of a noun subject, we have complex inversion (see 596, end).

Of the expressions in question, à peine ‘scarcely’ nearly always causes inversion, and peut-être ‘perhaps’ and sans doute ‘doubtless’ usually do so (except when followed by que – see below and 642), e.g.:

A peine se fut-il assis que le train partit

Scarcely had he sat down when the train started

Peut-être arrivera-t-il demain

Perhaps he will arrive tomorrow

Sans doute ma sæur vous a-t-elle écrit

Doubtless my sister has written to you

but also, as an alternative, Peut-être qu’il arrivera demain, etc.

Toujours is always followed by inversion in the expression toujours est-il que … ‘the fact remains that …’

Among other adverbs and adverbial expressions that frequently (and in some cases more often than not) cause inversion are:

| ainsi, thus | encore plus, even more |

| aussi, and so | en vain, in vain |

| aussi bien, and yet | rarement, rarely |

| du moins, at least | tout au plus, at most |

| (et) encore, even so encore moins, even less | vainement, vainly |

Inversion also sometimes occurs after various other adverbs. Examples:

Ainsi la pauvre dame a fini (or a-t-elle fini) par s’échapper

Thus the poor lady ended by escaping

En vain luttait-il (or il luttait); rien ne lui réussit

In vain he struggled; nothing went right for him

Vous avez demandé des nouvelles de son mari! Mais on vient de l’arrêter; du moins on le dit (or le dit-on)

You inquired after her husband! He has just been arrested; so they say at any rate

Tout au moins auriez-vous pu m’en avertir plus tôt

At least you might have warned me sooner

Note that ‘at least’ in its literal sense, i.e. before an expression of quantity, is always au moins and that, in this case, there is no inversion, e.g.:

Au moins trois cents personnes en moururent

At least three hundred people died of it

601 A different type of inversion is that in which the verb (which may or may not be preceded by an adverbial expression) has relatively little significance and serves mainly to introduce the subject which is the really important element. In equivalent sentences in English, the verb is regularly introduced by a meaningless ‘there’ or ‘it’, e.g.:

Suivit une âpre discussion en russe (Duhamel)

There followed a sharp discussion in Russian

Restent les bijoux (Chamson)

There remain the jewels

Reste à voir ce qu’il fera

It remains to be seen what he will do

A ce moment surgit un petit homme en casquette (Benoit)

At that point there appeared a little man in a cap

602 (i) Spoken registers of French (for the term ‘register’ see 13; for literary registers, see v below) make considerable use of a procedure known as ‘dislocation’ whereby an element is taken out of the main structure of the clause, repositioned before or after the rest of the clause, and recalled or anticipated by a conjunctive pronoun, e.g.:

(a) Paul, je le connais

(b) Je le connais, Paul

I know Paul

which, literally, mean ‘Paul I know him’ and ‘I know him Paul’ respectively: the direct object Paul, is taken out of the main structure of the clause and recalled (in a) or anticipated (in b) by the corresponding direct object pronoun le. Because of the positions the dislocated elements occupy on the printed page, type (a) is known as ‘left dislocation’ and type (b) as ‘right dislocation’.

If the dislocated element is a personal pronoun, the disjunctive form (see 215) is used, e.g. Moi je le déteste or Je le déteste, moi ‘I hate him’.

It is impossible here to discuss all the multifarious forms taken and roles played by dislocation. These depend on a complex interplay of factors which include the level of formality or informality of the discourse, the identification of the theme or topic of the sentence (i.e. what the sentence is talking about) and emphasis. Furthermore, two or more sentences containing dislocation that are identical in print may be clearly differentiated in speech by intonation and/or emphasis. For this and related constructions, see R. Ball, Colloquial French Grammar (Oxford, Blackwell, 2000), pp. 130–149.

The following notes cannot do more than draw attention to some of the more common types of dislocation.

(ii) A sentence such as Je connais Pierre ‘I know Peter’ can be dislocated in the following ways, with differences in intonation and subtle differences in role:

Moi, je connais Pierre

Je connais Pierre, moi

Pierre, je le connais

Je le connais, Pierre

Moi, Pierre, je le connais

Pierre, moi, je le connais

Je le connais, moi, Pierre

Je le connais, Pierre, moi

Moi, je le connais, Pierre

Pierre, je le connais, moi

As a further complication, note that some or all of the commas (representing pauses) in the above examples could be omitted.

The above examples involve dislocation of the subject and/or direct object. However, other elements can also be dislocated as the following examples show:

Je lui écris souvent, à Pierre

A Pierre, je lui écris souvent

I often write to Peter

J’y vais souvent, à Paris

A Paris, j’y vais souvent

I often go to Paris

J’en connais beaucoup, d’Américains

I know a lot of Americans

(iii) Right dislocation, as in Je le connais, Pierre ‘I know Peter’ and the last three examples in ii above, tends to be thematic, i.e. to clarify the information given by the conjunctive pronouns (le = Pierre, lui = à Pierre, y = à Paris, en = Américains) – the ‘core’ of the meaning, the ‘new’ information, is conveyed in these examples, but not necessarily in all sentences, by the verb; e.g. in Je lui écris souvent à Pierre and Il y va souvent à Paris, the new information the speaker wishes to convey in relation to the theme (Peter and Paris respectively) is that ‘I write to him’ and ‘He goes there’.

Left dislocation can also be thematic, but sometimes with greater emphasis on the dislocated element than with right dislocation.

(iv) In left dislocation, but not in right dislocation, there is a further possibility which is perhaps most clearly illustrated by such examples as the following:

Pierre, je lui écris souvent

I often write to Peter

Paris, j’y vais souvent

I often go to Paris

in which the preposition à does not figure before Pierre and Paris even though the meaning is ‘to Peter’, ‘to Paris’ – it is sufficient that this is made clear by the conjunctive pronouns lui and y respectively. What we have here is what is known as a ‘hanging topic’, i.e. one that is not integrated into the grammatical structure of the sentence. The following is a further example:

Des Américains, j’en connais beaucoup

I know a lot of Americans (lit. Americans, I know a lot of them)

This procedure can be taken further, in that the hanging topic relates not to some element expressed as such in the rest of the sentence but to something that is merely implied, as in Baudelaire’s well-known line:

Moi, mon âme est fêlée

My soul is cracked

in which moi ‘I, me’ relates to the personal pronoun that is implied in the possessive mon ‘my’.

This construction can have an emphatic value, as in:

Mon père, il ne faut rien lui dire

My father mustn’t be told anything

(v) As has been mentioned above, dislocation is especially characteristic of informal spoken French. It has, however, become the norm in literary French in the following circumstances:

(a) in certain contexts when a personal pronoun is to be stressed (see 216,i)

(b) with complex inversion (see 596,iii).

(vi) Fronting

‘Fronting’ (which is sometimes considered as yet another type of dislocation) means bringing to the beginning of the clause an element that normally follows the verb. It differs from dislocation (as defined above) in that the fronted element is not recalled by a conjunctive pronoun, e.g.:

Ces gens-là je connais

Those people I (do) know

It is much less common than dislocation and care must be taken not to use it in contexts where left dislocation, with the use of a conjunctive pronoun, is the appropriate construction. Fronting often serves to mark a contrast, e.g.:

Je n’aime pas Paul mais Pierre j’aime beaucoup

I don’t like Paul but Peter I like very much

Il téléphone souvent à sa sæur mais à sa mère il écrit

He often phones his sister but to his mother he writes

Je vais de temps en temps à Paris mais à Strasbourg je vais souvent

I go to Paris occasionally but Strasburg I often go to