4

Safety First 1922–9

COMMUNICATIONS

The British railway network was created in Victoria’s reign. In 1837 there had been only 500 miles of track; by 1901 the network was virtually the same in extent as it was to be in 1960. It actually reached its maximum between the world wars, with lines totalling just over 20,000 miles. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century more than 300,000 men were employed on the railways. The railway companies were vast enterprises, the pioneers of big business in Britain, with a share capital of over £1,250 million at 1913 prices.

The position of these companies was recognized as containing an element of monopoly and, though the nineteenth century is thought of as the heyday of laissez-faire, they had therefore been subject to a good deal of parliamentary regulation, stipulating the provision of early-morning ‘workmen’s trains’, for example. Some Liberals (Churchill was one) wanted to push the case for protecting the public interest one step further through nationalization of the railways. It looked as though this might happen during the First World War since the railway companies were put under state control, though administered through their existing managers, in a way typical of Lloyd George’s leanings towards corporate solutions. It seemed portentous that his Government set up a Ministry of Transport at the end of the war – what was the need if not to run nationalized railways? But instead the cry of ‘decontrol’ carried the day and the old corporate arrangements were rejigged (until after the next war).

With decontrol in 1921 came an amalgamation into four great companies: Southern; London, Midland, & Scottish (LMS); London and North Eastern Railway (LNER); and Great Western Railway (GWR). With their distinctive liveries and regional attachments, they inspired an almost patriotic loyalty, especially in retrospect when infused with nostalgia for the great days of steam, on which British industrial pre-eminence had been built. The spectacle of the Mallard, in LNER colours, establishing the world record speed of 126 m.p.h. for a steam train was one which many found inspiring in 1938; not only small boys whose hobby was ‘train-spotting’ but countless grown-ups lined the track for a fleeting glimpse of the mighty locomotive as it sped on the east-coast line between London and Edinburgh. With the electrification of the commuter lines on the Southern Railway well under way, however, this celebration of British mechanical prowess was already tinged with elegy.

Great Britain was knitted together by its railway network. No two stations were more than a whole day’s journey apart. Rich and poor used the train; luxurious dining and sleeping carriages, First Class and Third Class compartments (no Second Class since the nineteenth century), offered a service for all pockets. By 1901 there were well over 1,000 million passenger journeys a year; by 1913 1,500 million; in 1920 a peak of over 2,000 million. This represents a train journey every ten days for each man, woman and infant in Great Britain. Obviously that is not how the network was used. In the inter-war period about a third of the journeys were by holders of season tickets, mainly commuters, who can be presumed to have travelled twice each working day. But excluding the season-ticket holders still gives an average of one journey every twelve days.

Most of the railways’ revenue came from freight. Since it could only be transported between railheads, this implied a vast system of secondary distribution on short-haul journeys to the ultimate destination. This is where the horse and the iron horse formed their characteristic Victorian partnership. There were 3.5 million horses in Great Britain at the peak in 1902. The coming of the railway had boosted the number of horses used in urban Britain; conversely, the coming of the internal combustion engine was to signal their common eclipse, sooner or later. The demand for vast numbers of horses on the western front is often overlooked; when transport ships were sunk in the English Channel, the sea was full of hay. Nonetheless, the number of horse-drawn vehicles, over a million in 1902, had slumped to 50,000 by the end of the 1920s. Immediately before the First World War more than 500 million tons of freight was being carried annually by rail. The peak post-war figure was only two-thirds of this level and in the early 1930s it dropped to half. Part of this decline was due to the slump; but the failure to bounce back above 300 million tons a year during the recovery of the mid-1930s shows the potent competition now offered by motor vehicles, which could deliver goods from door to door in a single journey.

The railways, however, were still unrivalled in two specialized kinds of freight which facilitated communication through the written word. They carried nearly all the mail, enabling the Post Office to provide a cheap service of extraordinary efficiency throughout the country. This achievement was to be rhapsodized by the GPO film unit’s documentary Night Mail (1936), which, with its commentary by W. H. Auden – ‘This is the Night Mail crossing the Border, / Bringing the cheque and the postal order’ – has become a classic. During the war, post had generally reached troops in the trenches within two days. The total number of letters, postcards and packets posted in the United Kingdom was over 5,000 million in 1920 – about four items a week for each adult; and mail traffic was to rise in every decade until the 1970s. Mail trains, moreover, were paralleled by newspaper trains, running overnight, which made it possible to achieve national distribution of London daily newspapers throughout most of England and Wales.

It was this distribution network which enabled British national newspapers to gain a circulation unparalleled anywhere in the world. Scotland was protected not only by distance but also by cultural nationalism. At the top of the market, the Scotsman, printed in Edinburgh, continued to hold its own throughout the century. Scottish editions of most national newspapers were printed in Glasgow, facilitating distribution on Clydeside, where most of the customers lived. The Daily Record, for example, was a lightly transmogrified version of the Daily Mirror. One way or another, mass-circulation newspapers were London newspapers.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, with the development of wire services like the Associated Press, the provincial press had been a great force. Newspapers like the Manchester Guardian, the Yorkshire Post and the Western Daily Post, often under the control of editor-proprietors, relied primarily upon a bourgeois readership with a strong sense of regional identity. Merchants and brokers on the Manchester cotton exchange, for example, relied on the Manchester Guardian for its commercial pages, not for the left-wing Liberal politics which C. P. Scott propagated. It was to be unique in achieving a national circulation by the middle of the century, just like a London paper; it followed this logic by renaming itself the Guardian in 1959 and by effectively relocating to London in 1970. But the mass-circulation papers printed in London steadily seized the market. Already under pressure in the Edwardian period, the forty provincial morning papers which survived the First World War faced competition of a wholly new intensity. By 1937 only twenty-five remained.

It was Alfred Harmsworth’s Daily Mail in 1896 which first showed the possibilities of a national daily paper, selling at a halfpenny, and relying on advertising revenue to offset the low cover price. This was frankly aimed at the lower middle class, especially the growing numbers (of both sexes) in clerical jobs. Harmsworth had made his money in the 1890s with weekly papers geared to the interests of women; he insisted that the Daily Mail develop a women’s page as well as a sports page. With the Daily Mirror in 1903 Harmsworth even tried the experiment of a paper written by as well as for women. When it failed to prosper, it was relaunched in the following year in a new format, only half the size of the conventional broadsheet. Harmsworth called this ‘tabloid journalism’; it specialized in news photographs, using improved technology to produce halftone pictures with new speed and quality. Here too Harmsworth was revolutionary, though he cribbed many of his other ideas from the USA.

The striking innovation of the rival Daily Express, founded in 1900 with R. D. Blumenfeld as editor, was to put news on the front page, at a time when other papers consecrated it to grey columns of classified advertisements. Popular papers henceforth used ‘streamers’ which broke across more than one column, or splashed the main news in a ‘banner’ right across the page, with multi-deck headlines to lead the readers’ interest into a story. Harmsworth resisted this in the Daily Mail, and he showed a similar disdain for the prominence of advertisements, blenching at the course of the revolution which he had begun. Display advertising spread across several columns, using bold founts and pictures to get the message across. The London department store, Selfridge’s, was a pioneer in taking full-page advertisements, illustrated with line drawings.

The war not only made news and sold newspapers: it taught quality newspapers about news values. The main news page of The Times in Edwardian days was a relentless compilation of the ‘latest intelligence’ from around the world, with no headlines spreading beyond the column, and little indication in them of the substance of the stories, let alone sub-heads to lead a busy reader through the thicket of closely packed print. It was during the war that clear priority was signalled for the urgent news, which was sometimes put on to the front page (instead of customary columns of personal advertisements). By the 1930s The Times was ready for a facelift from the print designer Stanley Morison, who created the Times Roman fount, which has become a classic. Headlines for the first time broke across more than one column, though it took another thirty years before the paper became the last of the dailies to put news on the front page.

To British newspapermen of the first quarter of the twentieth century, this was a golden age, when giants stalked Fleet Street and Governments hung on every word which dropped from the press – or so it seemed when they wrote their (copious) memoirs. In the Edwardian period famous editors like J. A. Spender of the Liberal Westminster Gazette and J. L. Garvin of the Conservative Observer could build great reputations on the strength of the leading article alone, relying upon indulgent proprietors to support their endeavour to shape the fate of the nation. The new press lords, however, were unashamedly interested in giving the public what it wanted.

Alfred Harmsworth acquired a peerage in 1905, as Lord Northcliffe, and completed his journey to respectability by acquiring The Times in 1908. The first of the press lords, Northcliffe was emulated by others, not least in the sonorous titles they chose: Lord Rothermere for Alfred’s brother Harold Harmsworth, who kept the Daily Mail in the family; Lord Beaverbrook for Max Aitken, who had bought the Daily Express in 1916; Lord Southwood for J. B. Elias of the Odhams Press, which went into partnership with the TUC in 1930 to resuscitate the Daily Herald; Lord Camrose for William Berry, the proprietor of the Daily Telegraph from 1928, while for his brother Gomer, with whom he had earlier built up the Sunday Times, there was a peerage in due course as Lord Kemsley. Lloyd George’s friend, George Riddell of the News of the World, however, stuck with plain Lord Riddell.

The fall of Asquith was rather indiscriminately attributed to the power of the press; and Northcliffe was certainly an imperious figure who was determined to make his influence felt. (His growing megalomania indeed was pathological, and he died in 1922.) It is true that Lloyd George cultivated the press in a manner that was only later to become commonplace among ministers. The fact that his was a Coalition Government, lacking a declared party basis, also helped inflate the reputation of the press as a proxy for public opinion. Beaverbrook thrived in the Coalition milieu; Max loved to pick up the champagne bills when he kept open house for LG and FE and Winston, in an era when parties seemed to have replaced party as the glue of politics. Just as Northcliffe’s Daily Mail had pioneered a popular daily press, so Beaverbrook’s Daily Express set the pace in the race to mass circulation in the inter-war period.

At the end of the First World War, national dailies were selling 3 million copies; by the beginning of the Second, their sales were over 10 million. The Daily Express was the first to sell over 2 million a day in the mid-1950s; the Daily Mail was selling 1½ million; the TUC’s revamped Daily Herald more than 1 million; and the News Chronicle (a recent amalgamation of the two surviving Liberal popular dailies) somewhat less. Their circulation wars in the early 1930s, with as many as 50,000 canvassers offering rival editions of encyclopedias and sets of classic novels as free gifts, had helped drive up these figures, albeit at a heavy cost. By 1934, 95 morning and 130 Sunday papers were sold for every 100 families in Britain.

The role of newspapers was both buttressed and challenged by the rise of the newer media. The film industry, with its star system, created a whole new realm of human-interest stories; newspaper publicity helped to promote films and a good way of selling newspapers was to write about Hollywood, which provided 95 per cent of the films shown in Britain in the 1920s. The cultural threat of Americanization had always aroused fears among traditional elites in Britain; when it meant rampant commercialization it also aroused the suspicions of the anti-capitalist left. Here was the making of a consensus which helped ensure that radio broadcasting would be developed under public auspices rather than left to the free market.

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) was the result. It built upon the Post Office’s responsibility for regulating radio transmission, and, after a transitional period, was finally established in 1927 as a public corporation, under a board of governors appointed by the Government, vested with a monopoly of public radio broadcasting. By charging an annual licence fee for radio receivers, the service was freed from dependence on advertising. Indeed, the strict BBC code of the early years forbade any mention of brand names on the air. This was an arrangement which suited the press lords well since commercial radio would have threatened their advertising revenue. Broadcasting boomed from the start. The number of licences grew from 125,000 in 1923 to nearly 2 million by 1926, 3 million by 1930.

The precarious semi-autonomous status of the BBC was converted into an ethic of independent public service by its strenuous Director-General, John Reith, still in his thirties. High-minded, puritanical, domineering, Reith dedicated his life to the improvement of public taste through a carefully regulated regime of programmes, with just enough concessions to variety, entertainment and popular music to stave off mutiny by the listening public. The careful elocution of the BBC announcers was all part of Reith’s master plan for ‘improvement’: helping to establish one variant of an upper-middle-class London accent as ‘standard English’. Only on the regional networks were other accents regarded as acceptable.

The regime which Reith initially imposed was based on giving the public what he thought was good for them. In belated overcompensation for his own failure to secure a place at one of the ancient universities, he packed the BBC with Oxbridge graduates. Donnish talks enlightened the listening public on topics which ought to have interested them. Music meant live relays of symphony concerts, hogging the prime-time slots, evening after evening, with dance bands only allowed on the air after the normal programmes had finished. There were long-lasting triumphs along the way. Sir Henry Wood’s Promenade Concerts were saved by the intervention of the BBC in 1927; and the subsidized Proms became a feature of summer broadcasting for the rest of the century. Broadcast drama needed to innovate since relays from West End theatres did not work. This prompted the BBC to develop studio performances in adaptations of plays suitable for the microphone.

The BBC thus began by catering to minority tastes, but it was overtaken by its own success. From 3 million licence-holders in 1930, the number doubled by 1934 and trebled by 1939 – not far short of saturation coverage. The ‘cat’s whiskers’ of the early days, with headphones running off a crystal set, offered a hobby in the tradition of fiercely individualist artisan tinkering; but the valve radio sets on sale by the 1930s, with their tasteful Art Deco modelling, claimed pride of place in the family sitting room for a shared experience. To have missed a popular programme became a minor social disability, excluding the non-listener from a range of common references.

In Reith’s later years there was a more flexible adjustment of the programme schedules and the BBC even began to use listener research to find out more about its audiences. Listeners were thus permitted to tap their feet to famous dance bands like those of Henry Hall and Jack Payne. The launch of Band Waggon in 1938, starring Arthur Askey and Richard Murdoch, signalled the emergence of a new breed of radio comedians who were not just stand-up comics but began to develop a real situation comedy. Special events were covered by outside broadcasts. Cricket commentaries were particularly successful, with the slow unfolding of the game, hour by hour and day by day, lending itself to verbal transmission. Millions who never saw the great Australian batsman Donald Bradman nonetheless listened to him destroying England’s bowlers. Radio coverage of test matches developed into a minor art form, so much so that it was able to withstand the later competition from television. From 1931 the University Boat Race between Oxford and Cambridge improbably acquired a large vicarious following through live coverage from the BBC launch by John Snagge (educated at Winchester and Pembroke College, Oxford), one of the best-known announcers on the National Programme.

The frankly posh tones of the newsreaders, who were required to wear dinner jackets in the early days, may have helped buy credence for the BBC’s authoritative pretensions. Its claims to impartiality and objectivity were seldom challenged. There was no overt political bias, just a reflection of the fact that the BBC aspired to become part of the Establishment. Its duty to represent the Government’s position was impressed upon it behind the scenes at times of perceived crisis, notably the General Strike, which it weathered with some characteristic trimming by Reith. During election campaigns the parties were allowed air time which they initially misused by treating the microphone like a public meeting. Baldwin was the first to project a fireside manner successfully; radio was a medium for which his curiously intimate talents in communication were well suited. The Baldwinian ascendancy and the Reithian ascendancy coincided nicely. Reith’s balancing act was successful in cultivating an ethos of public broadcasting which survived him – he was eased out in 1938 – and in preparing the way for the BBC’s apotheosis as a national institution during the Second World War.

RIGHT, LEFT, RIGHT

The fall of the Lloyd George Coalition in October 1922 stemmed from a conscious decision by most of the Conservative Party, eagerly endorsed by Asquithian Liberals and Labour, to restore the party system. This was indeed accomplished, but not directly. Not only did it take until 1924: what was restored was a new party system – much more favourable to the Conservatives than the old, with Labour as the natural party of opposition. During the next seventy years the Conservatives were only to be out of power for eighteen.

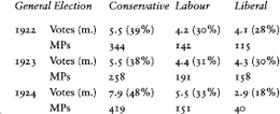

Three general elections were held in quick succession. In 1922 the Conservatives won a majority, only to lose it again in 1923. The first Labour Government took office in 1924, for a few months only, until a further general election gave the Conservatives a secure majority. For the Liberal Party, these were like successive punches to the head of an ageing heavyweight: a right jab which caught it off balance, a deceptive left which set it up for more punishment, and a devastating right swing which put it out for the count.

The influence of the electoral system itself on these results is worth noting. The Conservative triumph of 1922 and the Conservative set-back of 1923 were each achieved on virtually the same share of the poll. It was the distribution of the vote between their opponents that made the difference. On one flank, in 1923 the Liberals succeeded in winning half of the agricultural seats, in a style reminiscent of their strong performance in by-elections in the days of the pre-war Land Campaign – a message which Lloyd George took to heart in bringing forward new land proposals in 1925.1 On the other flank, Labour was steadily consolidating its position as the party of urban and industrial Britain, with a string of victories in working-class constituencies, not only in the coalfields as hitherto, but in most of the big conurbations. This was class politics, but with some curious twists. In the two British cities most divided on ethnic and religious lines, this sort of cultural politics worked for Labour in Glasgow, allowing it to gather Catholic votes, but against it in Protestant Liverpool; so a phalanx of Clydesiders, but not Merseysiders, appeared as Labour MPs.

In general the fact that Labour’s support was skewed on class lines was a clear advantage under the first-past-the-post system. Concentration of its support gave Labour more seats than the Liberals on the same share of the national vote. It was not that the Liberals were a third party nationally, subject to a squeeze on their support through fears of wasted votes: this was a secondary handicap that they faced chiefly from 1924. The fact was that they were the wrong sort of minority party, with support spread fairly evenly throughout Great Britain, and across social classes. This had been an advantage before the war; but became a fatal handicap when their national vote fell below a critical threshold. The crude logic was that they were able to finish second to Labour in working-class constituencies, second to the Conservatives in middle-class constituencies.

Under the three-party system of the 1920s a party that could nudge 40 per cent was a potential winner, a party stuck on 30 per cent was an also-ran. Yet in many electoral systems, of course, a party with 30 per cent of the votes is formidably represented. Here the Liberals had only themselves to blame for fumbling their opportunities to reform the voting system during the twelve years in which they had held a majority in the Commons, culminating in a Reform Act in 1918 which, almost at the last minute, abandoned the measure of proportional representation which was initially part of the package.

The Conservative backbenchers relished their display of power in repudiating the Coalition in 1922; thereafter they were to institutionalize their regular meetings under the name ‘the 1922 Committee’.1 After the Carlton Club decision to fight the next election on independent lines, Lloyd George obviously had to go, but many Conservatives regretted this. Not only did Austen Chamberlain resign as party leader, allowing Bonar Law to pick up the reins which he had so recently laid down: the first-class brains of the Coalition cabinet – the fading laureate Birkenhead, the evergreen Balfour – spurned the new Government. Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, though enormously grand, stayed on – the last of an unbroken line of aristocrats since Canning had left the Foreign Office in 1827.1 Law formed his cabinet as best he could. He initially tried to get the Liberal McKenna to go back to the Treasury, which he had occupied under Asquith, in place of Sir Robert Horne, another Coalitionist. Only when this ploy failed was the inexperienced Baldwin promoted instead. This changing of the guard made it plain that partisan and personal allegiances were in flux.

The Conservative Party could hardly repudiate the entire record of a Coalition Government of which it had been the mainstay. Much was therefore left unsaid during the election campaign in November 1922. The Conservatives lost 40 – but only 40 – of the seats which they had won in the Coupon Election. This showed that they had a future with or without Lloyd George. Without was the preference of many, notably Baldwin, who accordingly took comfort from the result. By contrast, Austen Chamberlain, who had loyally stuck to Lloyd George through thick and thin, found that he had yet again played the game and had again lost.

To refer simply to a ‘Liberal’ performance in the 1922 general election can be misleading. The ‘National Liberals’ under Lloyd George had no interest in alienating Coalitionist goodwill; and many of them enjoyed at least tacit Conservative support. Lloyd George and Asquith each had between fifty and sixty followers in the new parliament. This was a come-down for Lloyd George, still licking his wounds, but a welcome boost for Asquith, if only in comparison with his previous weakness; though in many constituencies ‘prefixless’ Liberals were what the activists really wanted.

The real gains were Labour’s. Given that a number of its victories in the Coupon Election had been by grace of the Coalition, Labour’s true strength was increased by up to 100 seats, putting it well clear of the Liberals, howsoever enumerated.

Labour had made a big advance since 1918. It was not due simply to the votes of trade unionists; with the onset of recession, their 5.6 million members could not have comprised more than 27 per cent of the electorate. Nor was it simply a product of the new parliamentary franchise. Labour’s increasingly broad appeal had come through in the 1919 local election results, fought on a register effectively based on household suffrage. The fact is that the Labour breakthrough was not sociologically determined but a product of the politics of the period. Its ability to channel the support of anti-Coalitionist forces in the country had been signalled in the Spen Valley by-election in 1920, when, fighting on traditional Liberal and Nonconformist territory, Labour had triumphed over both older parties. If Labour was now the people’s party, it was also becoming a toffs’ party – at least in its parliamentary leadership. The election as Labour MPs of educated professional men like Clement Attlee and Hugh Dalton showed the shape of the future.

For the present, a purely Conservative Government was a novelty – the first since 1905 (or even earlier, depending on how the Liberal Unionists are regarded). A proper peacetime cabinet of sixteen ministers was restored, though retaining the secretariat through which Hankey had serviced the war cabinet since 1917; the cabinet secretary henceforth occupied a key post in the power structure of Whitehall. The Government got off to an inauspicious start when Baldwin did a deal in Washington over the war loan – to pay the USA, on easy terms, irrespective of whether the UK was able to collect its own war debts – and, on docking at Southampton, leaked it to the press without squaring the cabinet first. He was lucky that most of them backed him – though not the prime minister, who first vented his feelings through an anonymous letter to The Times, attacking his cabinet’s proposed settlement, then caved in under the weight of City advice. This was an odd way of doing business; but Law hardly had time to make an impression as prime minister. Forced to retire from the Coalition on doctor’s orders in 1921, he had been given a clean bill of health in 1922, only to discover in May 1923 that he had terminal cancer. When he was buried in Westminster Abbey later that year Asquith remarked that the Unknown Prime Minister was being buried alongside the Unknown Soldier.

An unexpected vacancy thus opened in the leadership. Law had insisted on being elected as party leader before accepting the King’s commission as prime minister; but the constitutional propriety of doing things the other way around was now reasserted. Nor was this a mere formality, as it had been when Asquith succeeded Campbell-Bannerman. Since Chamberlain was out of the Government at the time, the choice was between Curzon, a long-serving cabinet minister, and Baldwin, with only a few months’ experience as Chancellor of the Exchequer. George V was thus faced with a decision of real weight. Since Law offered no advice, Balfour’s was sought. The old man, who harboured a feline malice for Curzon (‘dear George’), left his sickbed to go and see the King. Balfour’s case was that a peer was not acceptable as prime minister – a constitutional doctrine which might have surprised his uncle Robert but which certainly meant that ‘dear George’ was not chosen.

Stanley Baldwin was to be the pivotal figure in the government of Britain for the next decade and a half. Though his tenure was sometimes shaky, even as late as 1930, in the end he established an extraordinary grip on power. Under him the Conservative Party managed the transition to a fully democratic electorate, which it had so long feared, and weathered an economic slump which brought down regimes throughout Europe. Yet few predicted the rise of a Tory backbencher who had succeeded his father in the Worcestershire seat of Bewdley back in 1908: a wealthy ironmaster whose works were administered on old-fashioned paternalist lines, with time for a chat with men whom Mr Stanley had always known by their first names – a style which he effortlessly transferred to the Tea Room of the Commons, where he could be found, even as prime minister, hobnobbing with Labour’s old guard of trade-union MPs, over their pipes. All of this was good politics, especially when Baldwin projected heartfelt Christian verities and the sentiments of an English patriotism rooted self-consciously in the soil – all depicted with an art that sometimes reminded his hearers that Rudyard Kipling was a cousin.

Baldwin’s accession closed the door on Coalitionist projects. He wanted nothing to do with Lloyd George and was ready, if need be, to give Labour a chance in government. Nor was he hasty in mending his fences with the old Coalitionists. The new shape of the Conservative leadership was indicated by his choice at the Treasury, which went to the Minister of Health, Neville Chamberlain. Son of Joseph, half-brother of Austen, by whom he had hitherto been overshadowed, Neville was more faithfully a chip off the old block, both in his steely wish to succeed and in his retention of close ties with the economic and civic life of Birmingham. Only two years younger than Baldwin and even newer to the Westminster elite – Chamberlain was nearly fifty when he became an MP in 1918 – he exemplified the business ethic of the post-war Conservative Party. He too despised Lloyd George and the fleshpots of his Coalition; but he was naturally ready to welcome home the prodigal half-brother, should that prove possible.

As a Midlands industrialist, Baldwin had long been a Tariff Reformer, with an eye to domestic protection rather than any imperial vision; but he was no ideologue. He knew the electoral dangers of an issue that had happily lain dormant in Conservative politics for ten years. During the war it was the Liberal Chancellor McKenna who imposed duties on certain luxury goods, justified on the grounds that this rationed shipping space by price (rather than protecting domestic producers). But this was a fine line to draw, as was that between ‘protection’ and the measures of ‘safeguarding’ which the Lloyd George Coalition had introduced. After Versailles, to be sure, there was no large-scale resort to the sort of post-war economic warfare which many Free Traders had feared. The fiscal issue dropped out of prominence, assisted by Law’s pledge in 1922 that no change would be made in the next parliament. Why, then, did Baldwin revive the cry for protection?

Since the Government was precipitated into a general election which it lost, whereas it could have soldiered on for years, Baldwin met accusations of tactical ineptitude at the time. But since the chain of events led, within a year, to an impressive consolidation of the Conservative position, Baldwin has also been credited with a master strategy of great subtlety. He himself offered conflicting accounts. Though he proved adept at turning events to advantage, it is not clear that he foresaw the consequences of his declaration to the Conservative Party conference in October 1923 that Law’s pledge should lapse at the end of the parliament. His case was squarely based on unemployment, which he proposed to fight by protecting the home market. There is no need to doubt that he believed this; he knew it would go down well with his party; he knew too that Austen Chamberlain could hardly fail to rally to the cry of Tariff Reform, which headed off any new challenge from Lloyd George. Whether Baldwin also appreciated how soon an election would have to be called, once the genie was out of the bottle, is more doubtful; but he went ahead anyway.

The general election of 1923 was the nearest thing to a restoration of the pre-war party system, turning on the axis of Free Trade, with Liberais and Labour defending it from Conservative attack. The reunification of the Conservative Party around Tariff Reform was as nothing to the spectacle of the Liberal Party reuniting around Free Trade. Lloyd George and Asquith appeared on the same platform, their respective womenfolk hissing at each other beneath their breath. The fact is that, despite everything that had happened, the two men got on fairly well, left to themselves (though they seldom were by their stridently partisan followers). The Liberals racked their brains to remember the arguments that had served them well in 1906 and trotted them out again. The Liberal poll in 1922 had been an amalgam, still partaking of Coalitionist support in many places; the improvement in 1923 was thus substantial, showing surprising resilience in a party that could survive seven lean, mean years.

The rebuff to the Conservatives’ plea for protection was clearer in the parliamentary than in the electoral arithmetic. The Government had lost its majority, and Labour had appreciably more seats than the Liberals. Since Baldwin chose to meet the new House, rather than resign at once, there was time for reflection, which the Liberals would have been wise to put to better use. Asquith was not worried about a Labour Government as such; but he naively supposed that it could be sustained, to mutual advantage, by the ad hoc cooperation between the progressive parties which had worked when he had himself been prime minister. The Liberals therefore voted down the Baldwin Government. In allowing Labour to take office, without prior agreement on the terms on which Liberal support would be forthcoming, Asquith displayed a goodwill which he fondly hoped would be reciprocated.

The first Labour Government marks an epoch. On his return to the Commons in 1922, Ramsay MacDonald had narrowly been elected leader instead of J. R. Clynes, a Lancashire trade unionist who had been a stopgap, given the dearth of talent at Westminster since the Coupon Election. MacDonald’s opposition to the war had done him little permanent harm, given growing post-war disillusion, while it reinforced his left-wing credentials within the party. Ideologically, he remained a progressive in the mould of his old friend J. A. Hobson (now a Labour supporter), arguing that Labour represented this outlook more faithfully than the Liberal Party. Tactically, therefore, Mac-Donald was bent on replacing the Liberal Party.

The Government he formed in 1924 was a crucial step in achieving this objective. His defeated opponent Clynes was easily accommodated as Lord Privy Seal; Arthur Henderson became Home Secretary and J. H. Thomas Colonial Secretary. The Chancellor of the Exchequer was Philip Snowden, an intellectual equal of the prime minister and a colleague of thirty years’ standing in the ILP, where his fiercely moralistic utterances, though giving him an awesome reputation as a socialist, signalled a Gladstonian pedigree which made him welcome at the Treasury. These were Labour’s Big Five. Since MacDonald had more jobs than that to dispense, he had to root around for some of his other appointments, of which the most distinguished was the ex-Liberal Haldane as Lord Chancellor.

There was little in the policy of the Government with which Liberals disagreed. Snowden’s Budget was impeccable, so pure in its fiscal orthodoxy that it even abolished the McKenna duties. In the House Labour relied on Liberal support, not only in supplying votes but also some necessary legislative proficiency. For example, John Wheatley, the Clydesider who became Minister of Health, was responsible for one of the Government’s few effective measures, the Housing Act of 1924. Following the collapse of the Coalition’s building programme, Neville Chamberlain had put through a Housing Act in 192.3 which opened the field to private enterprise; what Wheatley did was to provide a state subsidy for the construction of council houses too. Though he received considerable help from the Liberals in passing the Act, this was not acknowledged.

The point was to demonstrate that Labour could form a proper Government. This MacDonald achieved. He served as Foreign Secretary as well as prime minister, playing both roles with aplomb, striking a handsome figure, seemingly at ease in even the grandest social circles – a point increasingly made against him. With every week that passed the idea of a Labour Government seemed less shocking, the notion of calling back Asquith more outlandish. The fact that Labour was gaining the kudos, while taking Liberal support for granted, naturally did little to improve relations between the parties. This was the real reason for the Government’s fall. The occasion was a vote of confidence in October on its handling of the prosecution of a Communist agitator – a trivial matter in itself had a concordat between Liberals and Labour been in force. As it was, the Liberals voted the Labour Government down, just as they had voted the Conservative Government down ten months previously.

Here was the flaw in the Liberals’ position. Having fought on the left in 1923, they were now fighting on the right in 1924. The election campaign showed that the fiscal issue had been consigned to oblivion – Baldwin in effect revived the pledge of inaction – and instead the issue was ‘socialism’. Little enough of this had been seen in action, but the very existence of a Labour Government was enough to fuel the Conservatives’ propaganda machine. MacDonald had spent a good deal of time trying to normalize relations with the Soviet Union, which was an opening for widespread allegations that the country was at the mercy of a Bolshevik conspiracy, aided and abetted by MacDonald. For those who needed evidence, Conservative central office excelled itself by producing an ostensibly compromising letter over the signature of the president of the Communist International, Zinoviev; and the Foreign Office managed to release the text while MacDonald himself was campaigning.

It is now known that the Zinoviev letter was a forgery; but it served its purpose in the election campaign; and it entered Labour Party legend as an example of Tory dirty tricks. In itself, however, its impact was probably marginal. The Labour poll, after all, went up by more than a million, or 3 per cent of votes cast on a higher turnout, giving Labour more seats than they had held in 1922, and establishing their clear role as the Opposition. What made the 1924 general election so decisive was what happened to the Liberal Party. This was a disaster worse than 1918. With a drop in their national poll to well under 20 per cent, the Liberals ended their career as a major party. Their 40 seats in parliament banished them to the ‘Celtic fringe’, holding constituencies in north Wales and the highlands of Scotland but almost wiped off the map in urban England.

Baldwin was now the master. The Conservatives benefited from the increase in turnout with almost. 2½ million extra votes. At nearly 8 million, they were in a different league to the other parties and within sight of an absolute majority of the votes cast. With over 400 MPs they were back to the golden days of Lord Salisbury. One attraction of the post-war Coalition had been as a great rally of moderate opinion against the threat of Labour; now the Conservatives had shown that they could achieve this on their own. The former Coalitionists were thus at Baldwin’s beck and call. His former leader, Austen Chamberlain, who had been in the cabinet before Baldwin was even in the House, served under him, as Foreign Secretary. Birkenhead was sent to the India Office. The aged Balfour prepared to return – the fossilized missing link with the party of Disraeli.

The most striking of the new appointments, however, was the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Amazingly, Neville Chamberlain did not want to go back to ‘that horrid Treasury’, preferring the Ministry of Health. So Baldwin turned to Winston Churchill, who was not even a paid-up Conservative at the time. Churchill had been deeply unhappy since the break-up of the Coalition, and was plainly no longer a Liberal except in the undiminished fervour of his attachment to Free Trade. He anticipated the new shape of politics by standing on anti-socialist lines at a by-election in 1924, before finding a berth at Epping as a ‘Constitutionalist’. The demise of the fiscal issue as the dividing line in politics was a precondition of Churchill’s return, after twenty years, to the Conservative Party; equally Baldwin could not have given a clearer signal of the new turn in Conservative strategy than by choosing Churchill.

ECONOMIC CONSEQUENCES

By 1924 it was clear that the British economy was less robust than it had been ten years previously. An obvious reason was the war. The most direct and frightening way of counting its cost was the total figure for the national debt, which in 1914 stood at £620 million – a burden far less in real terms than a far smaller population with far fewer resources had shouldered at the end of the Napoleonic wars. By 1920 the total public debt was nearly £8,000 million. Inflation helped make this manageable – prices in 1920 temporarily reached a level about two and a half times higher than before the war. Even so, the debt charges were a heavy load on the Budget in the 1920s: in round terms £300 million out of a total annual expenditure of £800 million. The standard rate of income tax, which the People’s Budget had so daringly raised from 1S (5 per cent) to 1S 2d (6 per cent), reached 6s (30 per cent) in 1919–22 and stood at 5s (25 per cent) at the beginning of 1924.1 On each £100 pounds of unearned or investment income, £25 went in tax, of which £10 simply serviced the national debt.

These were chiefly matters for financial adjustments between different groups of British citizens. After all, some of the public debt could have been paid off with accumulated private capital at the end of the war. Baldwin, whose ironworks had profited from war contracts, made a donation of £120,000 to the Treasury for this purpose – a fine but lonely gesture. A number of Liberal and Labour economists proposed a capital levy, partly appealing to social justice and partly to simple logic in breaking out of a crazy spiral. It was a spiral because many of the people who would have had to pay such a levy on their accumulated assets had not only benefited from debt-financed wartime expenditure but now held those assets in the form of war debt and were being taxed on the interest – in order to meet the Government’s debt charges. The money went round and round, though not, of course, to the equal advantage of everyone.

There was also, within the total, over £1,000 million of external debt, owed chiefly to the USA. This had to be financed by the UK across the foreign exchanges, in just the same way as reparations had to be financed by Germany. One way of meeting the costs of the war to the nation was out of its capital; British foreign investments had accordingly been run down during the war. Income from property abroad was one measure of this. In the 1920s this was still worth 5 per cent of GDP – as compared with I per cent sixty years later – but this was appreciably less than in the immediate pre-war years.

Britain’s magnificent foreign investments had thus served as a war chest; but the bottom line was that the UK had more need to pay its way in the post-war world through current earnings and current output. After the inflationary peak of 1920, commodity prices stabilized at about 175 per cent of their 1914 level. Invisible earnings, however, had not kept up with this increase; in the early 1920s they did not produce any more than pre-war in money terms. In real terms, therefore, the two items – rentier income from abroad and invisible exports – which had handsomely made up the pre-war deficit in visible trade were much diminished in value when measured at constant prices. This was not so, however, on the debit side of the foreign trade account. Measured at 1913 prices, the volume of imports was much the same as pre-war in the 1920s, whereas in real terms exports never again reached the 1913 level. What with the shortfall in property income and invisible exports, this meant that the balance of payments was now continually under strain.

The British export performance continued to rely on the old staples. In the exceptionally good year of 1920 coal still made up 9 per cent of domestic exports, only I per cent down on 1913. Cotton outdid itself by providing 30 per cent of all exports, an even higher share than in 1913; and the misplaced euphoria of this moment fuelled an investment boom in new mills, some of which never subsequently came into production. Coal was already slipping, relatively as well as absolutely, down by 1925 to 7 per cent of an export total which was itself below par. Cotton’s misery, exacerbated by the post-war over-expansion, was more prolonged: down to 25 per cent of all exports by 1925, well below 20 per cent by 1929, with worse to come.

The regional impact was devastating. In the export coalfields or north-east England and south Wales, and increasingly in Lancashire, communities found themselves with no future. When George Orwell published The Road to Wigan Pier (1937) he was writing about a town on the Lancashire coalfield where young men had traditionally gone down the pit and young women into the mill – a double catastrophe when both went bust. Markets for coal in eastern Europe, for textiles in Asia, were inexorably slipping to competitors with lower costs than Britain in producing these fairly unsophisticated goods. What is really remarkable, of course, is not that this eventually happened but that it took so long.

British export prices were crucially affected by three other prices: that of labour in the form of wages; that of the currency, as shown by the parity of sterling; and that of money, measured by interest rates. These prices were out of kilter in the 1920s, setting costs of production in Britain at levels which were no longer competitive, with resulting unemployment. If all these prices had been perfectly flexible, Britain might have adjusted to new trading conditions with some temporary dislocation but with no permanent loss. The signals of the market, indeed, provoked some diversion of resources to the new skills which were to flourish in the middle of the century – science-based industries like electrical goods and chemical processes, often geared to the demands of more affluent consumers, at home or abroad. A sign of the times was amalgamation which, in 1926, turned Brunner Mond into Imperial Chemicals Industries (ICI). This was what Americans had termed a trust, what we would now call a multinational, and it was paralleled by the soap company, Lever Brothers, combining with Dutch partners in 1929 to form Unilever. British industry does not therefore present an unrelieved picture of stagnation; but the widespread unemployment of the period surely points to a significant failure in market responses, faced with the challenge of change.

The biggest change was in labour costs. In 1924 the cost of living was 75 per cent higher than in 1914 but wages were nearly double. This meant that the standard of living for employed workers was at least 10 per cent higher than pre-war. Moreover, this understates the real gain since the normal working week had meanwhile been reduced by ten hours, or one-sixth. For employers, of course, it was a real problem to pay appreciably more for fifty hours’ work than they used to pay for sixty. Ideally productivity gains would fill the gap, but this was a tall order given the suddenness of the change. Producers for the domestic market might be able to pass on some of the increase in higher prices, but this course was hardly open in trades where prices were set by international competition. It is not surprising that export industries where labour constituted a high proportion of total costs should have run into recurrent trouble on the linked issues of pay and hours. Hence the great coal disputes of the period.

A second change affected the currency. At the outbreak of war the gold standard had been suspended. No longer was the parity of sterling fixed at $4.86; it traded at $4.76 for most of the war. The British Government maintained a commitment in principle to return to gold and kept hoping that the sterling and dollar rates would converge sufficiently to make this easy. In 1920 the average rate had been as low as $3.66; but it edged toward four dollars in 1921 and from 1922 to 1924 was around $4.40. This was a full 10 per cent short of the historic pre-war parity – or a mere 10 per cent, as some people preferred to put it. The option of returning to gold at this lower parity was not seriously considered. Since the object of the exercise was to restore confidence, to get back to the happy days of 1914, it was thought essential that the pound should, as the phrase went, ‘look the dollar in the face’.

Interest rates were the third crucial price. The Bank of England had historically set its discount rate at the level necessary to keep the gold reserves in equilibrium. Released’ from the obligation to sell gold at a fixed price, it had the alternative option of letting the exchange rate take the strain of a run on the currency. Such a course was inflationary, which is why City opinion was against it. Bank rate had gone as high as 7 per cent in 1920–21 to check the inflationary boom. This was one reason why the exchange rate subsequently strengthened, and this in turn permitted bank-rate to be lowered. By July 1923, the rate had stood for twelve months at 3 per cent before being raised by one point. Now interest rates of 3 or 4 per cent may not seem high, but the context of deflation should be remembered. Not only were prices falling: unemployment remained at least double its pre-war level. Industry was crying out for cheap money to lower its costs and make investment profitable again. The question was, did restoration of the gold standard require a prolonged dose of dear money?

This was the dilemma which Churchill faced on becoming Chancellor at the end of 1924. The weight of expert advice in favour of gold was formidable. The Controller of Finance at the Treasury, Sir Otto Niemeyer, marshalled the case for the Chancellor with steely logic. An advisory committee under the successive chairmanship of Sir Austen Chamberlain, twice previously Chancellor himself, and Lord Bradbury, a highly respected public servant and former head of the Treasury, came down in favour of an early return to gold. For Bradbury the economic arguments about whether sterling was overvalued against the dollar were secondary to the quasi-constitutional case for removing monetary policy from political influence. The great merit of the gold standard, he liked to say, was that it was ‘knave-proof’.

The ‘authorities’ – the Treasury and the Bank of England – stood firmly together. The Governor of the Bank, Montagu Norman, was an enigmatic, neurotic figure who, hardly less than God, moved in mysterious ways. He modestly affirmed that the Gold Standard was ‘the best “Governor” that can be devised for a world that is still human, rather than divine’. Such comments indicate a suspicion about the bad effects of political meddling that is partly timeless, as ongoing arguments about the role of a central bank sufficiently demonstrate; but this feeling was exacerbated in the mid-1920s by widespread revulsion against Lloyd George’s legerdemain and by fears of socialism. Government failure was more feared than market failure in opinion-forming circles. At the time when the decision had to be made, there were few voices against gold. As Labour’s Treasury spokesman, Snow-den could be counted in favour, and the position of the sceptical McKenna, the once and nearly Chancellor, now chairman of the Midland Bank, was not in the end clear-cut. In a double sense Churchill wanted to be persuaded of the case for gold: that is, he rigorously interrogated his experts rather than simply rubber-stamping their opinion, but his mindset was also one which prized the self-adjusting mechanism of traditional sound finance. In announcing the return to gold in his Budget speech in 1925 Churchill identified only one prominent critic.

This was J. M. Keynes, who was to capitalize on the fame he had acquired through his critique of Versailles by calling his case against the gold standard The Economic Consequences of Mr Churchill (1925). The crux of his argument was that, since sterling was overvalued, British costs would have to be brought down through a mechanism which Churchill, misled by the authorities, did not properly understand. It could only be done by using bank-rate to squeeze profits, intensifying unemployment as the means by which these fundamental adjustments would take place. Thus the argument was essentially about market flexibility. Churchill, consistent with his long-standing faith in Free Trade, was still assuming that the economic system would adjust to the parity of $4.86 which he now imposed, and that the gold standard simply shackled Britain to the realities of international competitiveness. Keynes suggested that too much had changed since 1914, meaning that unemployment would not be a transitory side-effect of adjustment but a chronic symptom of disequilibrium.

There is no need to castigate the gold standard as the root cause of all Britain’s economic difficulties in the late 1920s; but it did nothing to bring recovery at a time when the USA, for example, was enjoying a boom, while recovery in Britain remained as elusive as ever. Bank-rate, which had gone up to 5 per cent to launch the new parity, briefly dipped to 4 per cent on the strength of City sentiment but was back at 5 per cent by the end of 1925, and it stayed within half a point of this figure throughout the rest of the decade. The evidence of whether sterling was really overvalued is here; had it not been overvalued dear money would not have been needed, year in, year out.

Moreover, the deflationary effect of the policy can clearly be seen. Between 1924 and 1929, wholesale commodity prices fell by 17 per cent. In the same period the cost of living fell by more than 6 per cent. Money wages, however, hardly declined at all. One implication was benign: real wages, for those in work, rose from 11 per cent above their 1914 level in 1924 to 18 per cent above it five years later. The other implication spelt bad news for British industry and those who depended on it for jobs. The pressure of unemployment had not brought down wages to the extent required by the gold standard, and British costs accordingly remained uncompetitive. Modern estimates show that unemployment persisted in the range of 7 to 8 per cent. Since the level was higher in the insured occupations, the official figures, as published at the time, therefore showed unemployment at around 10 per cent.

With good cause, therefore, unemployment became a central issue in the politics of the period. Baldwin had offered to tackle it through tariffs in 1923. This approach was ruled out on electoral grounds in his new Government, except for the reinstatement of the McKenna duties, to which Churchill did not object. Otherwise his policy was constrained by the principles of sound finance, as traditionally conceived: Free Trade, the gold standard and balanced budgets. Given these assumptions, costs of production measured in sterling should have fallen to internationally competitive levels, so as to make sense of the ambitious parity of the pound at $4.86. But they did not. The Treasury privately complained that British workers were choosing unemployment instead; that trade unions insisted on maintaining existing levels of money wages, thus increasing real wages for those in work – at the expense of a million unemployed. The role of National Insurance in giving the unemployed a third option between work and starvation was also relevant. The principles of sound finance may have been as elegant as ever; it was their relevance to the real world that was now in question.

BALDWIN IN POWER

Baldwin set the tone of the new Government. His was a new Conservatism, seeking to establish a moderate consensus in clear opposition to Labour but abjuring the strident rhetoric of the class war. His most famous utterance of these sentiments came in a speech in 1925, when the Commons was debating a private member’s bill to abolish the trade unions’ political levy, thus cutting the Labour Party’s financial lifeline. Baldwin killed the bill in a wholly characteristic way, catching the ear of the House with a low-keyed emotional appeal, concluding: ‘Give peace in our time, O Lord.’ There is abundant testimony to the effects which he could achieve when on form, though print can hardly recapture the resonance of such addresses. Some were collected in the best-selling volume On England (1926), where he rhapsodized over ‘the sight of a plough team coming over the brow of a hill, the sight that has been seen in England since England was a land, and may be seen in England long after the Empire has perished and every works in England has ceased to function, for centuries the one eternal sight of England’.

Eternal? Baldwin was right to think that the Empire might perish, though he hardly foresaw that it would go out of business within forty years – barely surviving plough teams, and with a Conservative Government presiding over the obsequies. On paper at least, the Empire was at its fullest extent in the 1920s. Several of the former German colonies had been annexed under the peace treaties, with the League of Nations used to camouflage a division of the spoils between the victors. In west Africa, Britain and France partitioned Togoland and the Cameroons, but did so with an international mandate from the League to act as trustees. In east Africa, Britain got Tanganyika (and had even turned covetous eyes on Abyssinia for a moment) while German South West Africa was mandated to South Africa – which had conquered and occupied it during the war.

In the peace settlement possession inevitably made its own strong case: one which aided Britain in establishing a mandate over much of the Middle East. Here the Ottoman Empire’s intervention in the war on the German side had been successfully countered, mainly by the traditional British resource of deploying the Indian Army. True, Britain had long occupied Egypt; but by the Armistice large tracts of territory, from Jerusalem and Damascus to Baghdad, had been conquered under General Allenby’s command. The trouble was that, in the process, the British had given contradictory promises: to their French allies, promising them Syria; to their Arab allies, promising them much the same; and finally (the Balfour Declaration of 1917) to the newly influential Zionist interest, promising a Jewish national home. In Paris, Lloyd George had wriggled out of these diverse commitments as best he could, coming out of the negotiations with new British mandates over Palestine and Iraq. The war aim of self-determination, which had seemed to spell the end of imperialism, had plainly not stopped the post-war expansion of the British Empire, which now covered one-quarter of the world.

But it covered it thinly. British control had always meant empire on the cheap, relying on bluff to shore up its prestige and power. The new strategy was to assimilate the new territories by invoking the new technology of air power, subduing tribesmen in the most cost-effective way yet devised. It was the making of the Royal Air Force. Meanwhile, on the ground, British officials were haplessly caught in simmering conflicts which threatened increasingly during the inter-war years to come to the boil (and often did so after the Second World War). Thus as High Commissioner for Palestine, the Liberal ex-minister Sir Herbert Samuel, the embodiment of disinterested rationality, sought to mediate between immigrant Jews and aggrieved Arab nationalists, leaning over backwards (as a Jew himself) to reconcile the irreconcilable. In India, too, the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms, implemented in 1919, sought to propitiate a rising tide of nationalism through an extension of representative government, while squaring the circle of imperial control.

As for the Dominions, their de facto independence was to be recognized in the fuller definition of Dominion status formulated in 1926, accepted by the imperial conference of 1930, and enacted as the Statute of Westminster in 1931. The crown was thereby acknowledged as the symbol of the free association of ‘the British Commonwealth of Nations’. Thus the question of whether the Great War had reinvigorated the Empire, or pushed it into decline, could henceforth be ducked by pointing to the phoenix-like evolution of the Commonwealth. It was a concept which owed much to the Round Table group – often recruited from members of Milner’s ‘kindergarten’ in South Africa, like Philip Kerr (Lord Lothian) and Lionel Curtis, author of The Problem of the Commonwealth (1916). In their formulation, the Commonwealth was a laudable example of international cooperation, claiming strong affinities with the League of Nations, and drawing support from the same ecumenical swathe of liberal opinion to which Baldwin now pitched his appeal.

Britain’s real concerns remained focused on the Empire, where it had its hands full, perhaps its stomach too. This had been shown by Britain’s readiness, at the Washington conference in 1921–2, to accept not only naval parity with the USA but the American condition that the Anglo-Japanese alliance must be abandoned. Resources for another naval race were simply unforthcoming, as Churchill made clear while he was Chancellor; indeed it was he who institutionalized the ‘ten-year rule’, meaning that defence planning should assume no major wars within that horizon. Britain’s European role was therefore relatively attenuated. It saw itself as honest broker, sustaining the League of Nations, rather than as France’s ally, exacting vengeance on Germany. As Foreign Secretary, Austen Chamberlain was given a lot of latitude and achieved a gratifying personal success at Locarno in 1925. This was essentially a completion of the work begun by Lloyd George to welcome back Germany as a full partner – ‘no victor, no vanquished’ – and secure German assent to the post-war settlement, notably mutual recognition of frontiers.

Detailed policy-making, abroad or at home, was simply not Baldwin’s forte, any more than it had been Disraeli’s. Moreover, his public image was not always the face seen by his colleagues, who were sometimes exasperated at his inconsistencies and his apparent lack of strategic grasp. In domestic policy, the Government depended overwhelmingly on Churchill and Neville Chamberlain.

Neville Chamberlain had learnt to love the Ministry of Health in 1923 and returned in 1924 for a five-year stint, with his plans already prepared. He had a string of measures ready, some of them on technical lines, drawing on an expertise in local government which was unrivalled in his party. Lloyd George’s gibe, that Chamberlain had been a good lord mayor of Birmingham in a lean year, had some truth in it; but it also betrayed the disparaging attitude of the Westminster talking-shop for a minister whose executive grasp was seen to best advantage in Whitehall. Chamberlain was determined that a Conservative Government should show itself as fit as any Liberal or Labour Government to legislate on social questions.

Chamberlain took up pensions where Asquith and Lloyd George had left off. The withdrawal of older men from the labour force was to become one of the major social and economic changes of the twentieth century. Whereas in 1881 three out of four men aged over sixty-five were still at work, a century later nine out of ten had retired. It is tempting to see the Widows’ and Old Age Pensions Act of 1925 as the hinge of this change. This was an extension of the National Insurance scheme, providing for contributory pensions to insured workers or their widows, with sixty-five instead of seventy henceforth established as the pensionable age. The 1931 census, for the first time, recorded a majority of men aged over sixty-five as retired. Yet the level of pension was hardly enough to provide an incentive for retirement, although it may have cushioned it; and it was not until after the Second World War that retirement was made a condition for drawing the old-age pension. Chamberlain’s Act, significant as it was in recognizing the need for pensions, was following rather than setting a trend towards retirement at sixty-five.

What appealed to Chamberlain here was the administrative consolidation and the self-financing nature of the scheme in the long term. What seized the imagination of his colleague Churchill was the development of Tory Democracy, as preached by his father, so as to attach the self-interest of millions of contributors to the well-being of the capitalist system. The aid of the Treasury was needed to finance the transition until the point in the future when contributions would balance outgoings, since benefits became payable immediately. Through such interdepartmental negotiations Churchill and Chamberlain, though not personally close, reached a good working relationship. This was seen to best effect in the quid pro quo eventually embodied in the Derating and Local Government Acts of 1928 and 1929.

Chamberlain wanted nothing less than a comprehensive reform of all local government, subsuming the old Poor Law structure within the ambit of omnicompetent local councils. It was a complement to the Education Act of 1902, which had abolished the ad hoc school boards; now the functions of the ad hoc Poor Law Guardians were likewise to be given to specialist committees of existing local councils. The Act thus fulfilled the ambition to break up the Poor Law, as declared by the Webbs in their minority report twenty years previously. Local councils were to provide specialist services for childcare and for health. Old people’s homes were to replace the Poor Law’s provision for aged paupers – though since the same buildings often continued in use, old people for a generation were to continue speaking of going (or not going) ‘into the workhouse’.

The residual responsibility of the Poor Law – for the able-bodied destitute or unemployed – was given to new Public Assistance Committees, which local authorities were required to set up. This had the political attraction for Chamberlain of removing the hard-core unemployed, who had exhausted all benefits under the National Insurance scheme, from the ministrations of those Poor Law Guardians, in Labour-controlled areas, who had insisted on paying relatively high levels of relief. This practice, called Poplarism from the east London borough where it was prevalent, had not only bankrupted the Poor Law Unions in some of the unemployment blackspots but offered informal competition to the dole among claimants who often calculated which paid best. Chamberlain was now able to stamp out Poplarism as part of his grand design to clean up local government.

The design became even grander once Churchill got into the act. The fact that local government had long been financially dependent on central government gave the Chancellor his entrée. The old system was to give grants-in-aid from the Treasury for certain functions undertaken by local councils – so that the affluent areas which spent most got most, while the indigent, which needed most, got least. In place of this, Chamberlain’s rational mind devised a plan for Treasury block grants, related to assessed needs, area by area. Churchill would not agree to such a simple adjustment of public funding. Since he had to find the money, it was his plan which took over.

Its origin lay in Churchill’s frustration in face of persistent unemployment, which sound finance permitted him to tackle neither through tariffs nor through cheap money nor through devaluation nor through Budget deficits. He relied therefore on fiscal incentives on the supply side, to try to stimulate enterprise. Income tax, which had been reduced in Snowden’s 1924 Budget from 5s (25 per cent) to 4s 6d (22.5 per cent), was further reduced by Churchill in 1926 to 4s (20 per cent), at which level it remained until 1930. His distinctive scheme, however, was to relieve industry of local taxation. Industry was exempted from local rates (‘derated’) by a full 100 per cent and railways by 50 per cent.

The shortfall in revenue for local government was made up from central government – by redesigning the block-grant arrangements which Chamberlain had first suggested as a far bigger fiscal merry-go-round. Moreover, those who lost on the roundabouts would win on the swings – that was guaranteed by Churchill’s further provision that no local authority would suffer a net loss. The richer authorities, usually in Conservative areas, would not suffer in order to subsidize the depressed authorities, usually Labour. The political finesse of these arrangements can be gauged from the contrast with the comparable revolution in local-government finance, sixty years later: the ill-fated poll-tax experiment.

Initiated by Chamberlain, supported by Churchill, most of the Government’s social programme worked out according to plan. But Baldwin’s aspiration for ‘peace in our time’ was mocked by events. Although the Conservatives were determined to disentangle the state from responsibility for the coal industry, there proved to be no easy way of achieving this. The return to gold exacerbated the export difficulties in 1925 and prompted the mine-owners to cut wages. With the miners’ union, under its intransigent leader A. J. Cook, now threatening a strike, the Government agreed to pay a subsidy while a Royal Commission reported. This task was put in the hands of Sir Herbert Samuel, fresh from Jerusalem. The Samuel Report, published in March 1926, endorsed rationalization of the pits into larger combines to secure a long-term future for the industry, but in the short term advised that there was no alternative to some reduction in wages. The passionate response of the miners’ leader – ‘not a penny off the pay, not a minute on the day’ – showed that he was not on Samuel’s plane, hardly on his planet.

The Government was let off the hook. Restive backbenchers who thought Baldwin soft had been worried that he might settle. The bad tactics of the miners’ union, the bad grace of the mine-owners, the bad conscience of the TUC – perhaps the bad faith of the cabinet – now conspired to produce the long-heralded General Strike. It was actually selective rather than general. On 3 May 1926 the TUC brought out 1½ million key workers, mainly in energy and communications industries, in support of the miners. It is not clear what they hoped to achieve or how. A General Strike had often been regarded as a doomsday scenario, in which Government would be humbled by the might of organized labour. But the TUC leaders, like its general secretary Walter Citrine and Ernest Bevin of the Transport and General Workers’ Union (TGWU), had no ambition or illusion of revolution; they were responding, like many of their members, to a sentiment of loyalty, a feeling that they could not decently let the miners down. The Government, by contrast, had a simple strategy forced upon it – to resist.

Churchill’s combative instincts made him a prominent figure during the General Strike. Instead of sitting in 11 Downing Street, poring over the fine print of the next financial statement, he enjoyed a dizzy ten days as a newspaper editor, able to hold the front page whenever he dreamt up another bloodcurdling headline about the threat to constitutional government. His British Gazette had a virtual monopoly and exploited it without scruple to put the Government’s point of view. Its distribution far outran that of the TUC’s British Worker. The real competition was from the BBC, which Churchill wanted to take over too. Instead Reith stalled, Baldwin prevaricated; the worst that happened was that the Archbishop of Canterbury was kept off the air for fear that he might talk unseasonably about peace in our time. For many undergraduates the Strike was fun – the chance of a lifetime to drive a tram or, more rarely, act as an outrider for the march of the proletariat. The famous myth of the General Strike is that strikers and policemen played football – which they did, but only on the odd occasion, never repeated, rather like the Christmas truce in the trenches in 1914. In industrial areas where the issues were most pointed this was a real conflict while it lasted.

It only lasted for nine days. The TUC, desperate to call off an exercise that they could not win, seized on a compromise formula put forward by Samuel. The miners were thus again left to fight on, and did so with grim resolution, facing inevitable defeat. Once the Government had won, unexpected fissures appeared within the cabinet. It was now Churchill who spoke up for magnanimity, reaching out to offer an honourable retreat to a beaten foe; it was Baldwin who sat out the miners’ strike until they were starved back, on the owners’ terms, after a siege of six months. All told, 1926 was the worst year for industrial disputes in British history. More days were lost than in 1912, 1921 and 1979 put together. But it was the miners’ strike, not the General Strike, which accounted for 90 per cent of the total.

The General Strike had an impact on each of the political parties. The Tories thenceforth had their tails up, and in 1927 Baldwin let his backbenchers have the sort of bill which he had vetoed in 1925, stipulating that trade unionists must ‘contract in’ if they wished to pay the political levy, not, as previously, simply ‘contract out’ if they were opposed. The Labour Movement, conversely, opted firmly for moderation. Bevin became the dominant figure in the TUC, and the parliamentary party sought to assert its independence. For the Liberals, too, the General Strike was a turning point, as the occasion of a transfer of the leadership from Asquith to Lloyd George.

Asquith had hung on as leader, despite his own defeat at Paisley in the 1924 General Election, partly because his supporters still could not bear the thought of Lloyd George, who now led the Liberal MPs in the Commons. The Earl of Oxford and Asquith (as he became) was by this stage a remote figure, into his mid-seventies. When his henchman Sir John Simon endorsed the Government line that the strike was unconstitutional, Lloyd George had had enough and broke ranks; moreover he carried with him even left Liberals, like Keynes, with personal loyalties to Asquith. So Lord Oxford finally bowed out; he died in 1928. The factional animosities in the party went deep and were never to be fully healed. Asquithian loyalists, increasingly looking to Simon for a lead, were to set up their own Liberal Council as a party within a party. The Lloyd George political fund, instead of being a boon to the hard-pressed finances, became a bone of contention between the new leader and the old guard of Asquithians, like Viscount (Herbert) Gladstone, back in charge of the party machine, twenty years on from his days of glory as Chief Whip. For all that, as one Asquithian had the grace to admit, ‘when Lloyd George came back to the party, ideas came back to the party’.

Lloyd George succeeded in making the most of the Liberals’ remaining assets. Labour might have the trade unions and the Tories might have the money, but the Liberals were confident that they still had the brains. The Liberal summer schools, which Lloyd George patronized, were one way to enlist the intellectuals; the Liberal Industrial Inquiry which he set up was another. Its report in 1928, known as the Liberal Yellow Book, was full of ideas – perhaps rather too full – about the current state of the British economy and about what could be done to revitalize it through Government coordination and support. Some of these suggestions were hammered into a manifesto, under the direction of Seebohm Rowntree, which was published in March 1929 with the title We Can Conquer Unemployment. It was built around Lloyd George’s pledge to bring down unemployment to its pre-war level through a two-year programme of loan-financed public investment. The intellectual inspiration came from Keynes; the political leadership from Lloyd George.