CHAPTER 4

Literary Texts

You are probably familiar with many kinds of literary texts. Realistic fiction presents characters and situations that are familiar from real life. Science fiction describes things that might happen in the future. There are also fables, fairy tales, and legends. The literary passages that you will find on the GED® test come mainly from classic literature of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

These works of literature are rich in the language they use, the plots they develop, and the characters that they draw. Some of the writing may seem somewhat dated to you, but a careful reading of the text will help you understand what is happening in each passage. As you read, you should try to be aware of the elements that make up fiction. They are:

• Theme

• Plot or events of a story

• Characters

• Setting

• Narrator and character viewpoint

Using Textual Evidence to Analyze Elements of Fiction

Theme

The theme of a story is the central idea behind its events and characters. There are many different kinds of themes. For example, the theme of a story might be how a wronged person can obtain justice, or how difficult it is to make peace between enemies, or how a journey can bring wisdom to a traveler.

A theme is rarely stated directly. You must figure it out from what happens in the story, how its characters behave, and how the author describes the characters and events. You must base your choice of theme on the evidence in a text.

Directions: Read the following excerpt from Sherwood Anderson’s short story “Paper Pills.” As you read, try to identify the theme of the passage. Then answer the question.

1 He was an old man with a white beard and huge nose and hands. . . . [H]e was a doctor and drove a jaded white horse from house to house through the streets of Winesburg. Later he married a girl who had money. She had been left a large fertile farm when her father died. The girl was quiet, tall, and dark, and to many people she seemed very beautiful. Everyone in Winesburg wondered why she married the doctor. Within a year after the marriage she died.

2 Winesburg had forgotten the old man, but in Doctor Reefy there were the seeds of something very fine. Alone in his musty office in the Heffner Block above the Paris Dry Goods Company’s store, he worked ceaselessly, building up something that he himself destroyed. Little pyramids of truth he erected and after erecting knocked them down again that he might have the truths to erect other pyramids.

3 Doctor Reefy was a tall man who had worn one suit of clothes for ten years. It was frayed at the sleeves and little holes had appeared at the knees and elbows. In the office he wore also a linen duster with huge pockets into which he continually stuffed scraps of paper. After some weeks the scraps of paper became little hard round balls, and when the pockets were filled he dumped them out upon the floor. For ten years he had but one friend, another old man named John Spaniard who owned a tree nursery. Sometimes, in a playful mood, old Doctor Reefy took from his pockets a handful of the paper balls and threw them at the nursery man. “That is to confound you, you blathering old sentimentalist,” he cried, shaking with laughter.

4 The story of Doctor Reefy and his courtship of the tall dark girl who became his wife and left her money to him is a very curious story. It is delicious, like the twisted little apples that grow in the orchards of Winesburg. In the fall one walks in the orchards and the ground is hard with frost underfoot. The apples have been taken from the trees by the pickers. They have been put in barrels and shipped to the cities where they will be eaten in apartments that are filled with books, magazines, furniture, and people. On the trees are only a few gnarled apples that the pickers have rejected. They look like the knuckles of Doctor Reefy’s hands. One nibbles at them and they are delicious. Into a little round place at the side of the apple has been gathered all of its sweetness. One runs from tree to tree over the frosted ground picking the gnarled, twisted apples and filling his pockets with them. Only the few know the sweetness of the twisted apples.

5 The girl and Doctor Reefy began their courtship on a summer afternoon. He was forty-five then and already he had begun the practice of filling his pockets with the scraps of paper that became hard balls and were thrown away. The habit had been formed as he sat in his buggy behind the jaded white horse and went slowly along country roads. On the papers were written thoughts, ends of thoughts, beginnings of thoughts.

6 One by one the mind of Doctor Reefy had made the thoughts. Out of many of them he formed a truth that arose gigantic in his mind. The truth clouded the world. It became terrible and then faded away and the little thoughts began again.

7 The tall dark girl came to see Doctor Reefy because she was in the family way and had become frightened. She was in that condition because of a series of circumstances also curious . . . .

8 After the tall dark girl came to know Doctor Reefy it seemed to her that she never wanted to leave him again. She went into his office one morning and without her saying anything he seemed to know what had happened to her.

9 In the office of the doctor there was a woman, the wife of the man who kept the bookstore in Winesburg. Like all old-fashioned country practitioners, Doctor Reefy pulled teeth, and the woman who waited held a handkerchief to her teeth and groaned. Her husband was with her and when the tooth was taken out they both screamed and blood ran down on the woman’s white dress. The tall dark girl did not pay any attention. When the woman and the man had gone the doctor smiled. “I will take you driving into the country with me,” he said.

10 For several weeks the tall dark girl and the doctor were together almost every day. The condition that had brought her to him passed in an illness, but she was like one who has discovered the sweetness of the twisted apples, she could not get her mind fixed again upon the round perfect fruit that is eaten in the city apartments. In the fall after the beginning of her acquaintanceship with him she married Doctor Reefy and in the following spring she died. During the winter he read to her all of the odds and ends of thoughts he had scribbled on the bits of paper. After he had read them he laughed and stuffed them away in his pockets to become round hard balls.

Which of the following sentences from the story best represents its theme?

A. “For several weeks the tall dark girl and the doctor were together almost every day.”

B. “The tall dark girl did not pay any attention.”

C. “The knuckles of the doctor’s hands were extraordinarily large.”

D. “Only the few know the sweetness of the twisted apples.”

To answer this question, you need to consider what happens in the story. The characters say very little and the story is very short, so you can be sure that the author has chosen his words carefully. When we first meet Dr. Reefy, we are told he is an old man who had been “forgotten” by the town. The author brings particular attention to his large knuckles and nose, as if he is misshapen somehow, and yet the author says inside him are the “seeds of something very fine.” We also learn that he had a beloved and beautiful wife who died, and that the story of how they met and fell in love “is delicious, like the twisted little apples that grow in the orchards of Winesburg.” These apples, like Dr. Reefy, are twisted and abandoned. By the middle of the story, it is clear that the author is drawing a connection between Dr. Reefy and the twisted apples. The story also poses the question of why the tall girl falls in love with Dr. Reefy. We then find out that she came to him “in the family way” (pregnant) but that he is sweet and not judgmental, offering to take her riding and sharing his thoughts with her.

Finally, near the end of the story, the author is fairly specific, writing, “she was like one who has discovered the sweetness of the twisted apples, she could not get her mind fixed again upon the round perfect fruit that is eaten in the city apartments.” The best choice, then, is D, meaning that few people can understand the essential value and sweetness of some people that others view as outsiders.

Remember, on the GED® test, you will not only be asked to analyze the theme, you will be asked to tell which sentence from the passage most suggests the theme.

Directions: Read the following excerpt from the first chapter of Edith Wharton’s novel Ethan Frome. Think about how it establishes the theme of the novel. Then answer the question.

1 I had the story, bit by bit, from various people, and, as generally happens in such cases, each time it was a different story.

2 If you know Starkfield, Massachusetts, you know the post-office. If you know the post-office you must have seen Ethan Frome drive up to it, drop the reins on his hollow-backed bay and drag himself across the brick pavement to the white colonnade: and you must have asked who he was.

3 It was there that, several years ago, I saw him for the first time; and the sight pulled me up sharp. Even then he was the most striking figure in Starkfield, though he was but the ruin of a man. It was not so much his great height that marked him, for the “natives” were easily singled out by their lank longitude from the stockier foreign breed: it was the careless powerful look he had, in spite of a lameness checking each step like the jerk of a chain. There was something bleak and unapproachable in his face, and he was so stiffened and grizzled that I took him for an old man and was surprised to hear that he was not more than fifty-two. I had this from Harmon Gow, who had driven the stage from Bettsbridge to Starkfield in pre-trolley days and knew the chronicle of all the families on his line.

4 “He’s looked that way ever since he had his smash-up; and that’s twenty-four years ago come next February,” Harmon threw out between reminiscent pauses.

5 The “smash-up” it was—I gathered from the same informant—which, besides drawing the red gash across Ethan Frome’s forehead, had so shortened and warped his right side that it cost him a visible effort to take the few steps from his buggy to the post-office window. He used to drive in from his farm every day at about noon, and as that was my own hour for fetching my mail I often passed him in the porch or stood beside him while we waited on the motions of the distributing hand behind the grating. I noticed that, though he came so punctually, he seldom received anything but a copy of the Bettsbridge Eagle, which he put without a glance into his sagging pocket. At intervals, however, the post-master would hand him an envelope addressed to Mrs. Zenobia—or Mrs. Zeena-Frome, and usually bearing conspicuously in the upper left-hand corner the address of some manufacturer of patent medicine and the name of his specific. These documents my neighbour would also pocket without a glance, as if too much used to them to wonder at their number and variety, and would then turn away with a silent nod to the post-master.

6 Everyone in Starkfield knew him and gave him a greeting tempered to his own grave mien; but his taciturnity was respected and it was only on rare occasions that one of the older men of the place detained him for a word. When this happened he would listen quietly, his blue eyes on the speaker’s face, and answer in so low a tone that his words never reached me; then he would climb stiffly into his buggy, gather up the reins in his left hand and drive slowly away in the direction of his farm.

7 “It was a pretty bad smash-up?” I questioned Harmon, looking after Frome’s retreating figure, and thinking how gallantly his lean brown head, with its shock of light hair, must have sat on his strong shoulders before they were bent out of shape.

8 “Wust kind,” my informant assented. “More’n enough to kill most men. But the Fromes are tough. Ethan’ll likely touch a hundred.”

9 “Good God!” I exclaimed. At the moment Ethan Frome, after climbing to his seat, had leaned over to assure himself of the security of a wooden box—also with a druggist’s label on it—which he had placed in the back of the buggy, and I saw his face as it probably looked when he thought himself alone. “That man touch a hundred? He looks as if he was dead and in hell now!”

10 Harmon drew a slab of tobacco from his pocket, cut off a wedge and pressed it into the leather pouch of his cheek. “Guess he’s been in Starkfield too many winters. Most of the smart ones get away.”

11 “Why didn’t he?”

12 “Somebody had to stay and care for the folks. There warn’t ever anybody but Ethan. Fust his father—then his mother—then his wife.”

13 “And then the smash-up?”

14 Harmon chuckled sardonically. “That’s so. He had to stay then.”

15 “I see. And since then they’ve had to care for him?”

16 Harmon thoughtfully passed his tobacco to the other cheek. “Oh, as to that: I guess it’s always Ethan done the caring.”

17 Though Harmon Gow developed the tale as far as his mental and moral reach permitted there were perceptible gaps between his facts, and I had the sense that the deeper meaning of the story was in the gaps. But one phrase stuck in my memory and served as the nucleus about which I grouped my subsequent inferences: “Guess he’s been in Starkfield too many winters.”

What is the theme suggested by the passage?

A. Difficult life events can stifle personal desires.

B. Physical injuries can cause mental damage.

C. Love can help you conquer all challenges.

D. Small towns allow for close personal relationships.

To answer this question, first note that the novel is named after a character, and that character is immediately introduced. It seems clear that something about that character’s actions or decisions will form the backbone of the novel. We read that Ethan Frome was seriously injured in an accident—a “smash-up”—twenty-four years ago, and that he bears permanent injuries from the accident. We also learn that he rarely speaks to other people, but comes into town to pick up medicine for a Zenobia Frome, his wife. That might lead you to find choice B attractive, because Ethan’s behavior is a bit out of the ordinary. However, notice that the author repeats a phrase twice in the space of just a few paragraphs, and draws particular attention to it: “Guess he’s been in Starkfield too many winters.” The narrator says Ethan looks like he is in “hell.” We can guess by this that Ethan probably did not wish to remain in Starkfield, or that he had once had some other plans for how he wanted his life to turn out. We also learn that Ethan was—or at least felt—compelled to take care of family members who needed him. These details make it clear that choice A is the best selection.

Here is another example.

Directions: Read the following excerpt from the short story “The Open Boat,” by Stephen Crane. Then answer the question.

1 It would be difficult to describe the subtle brotherhood of men that was here established on the seas. No one said that it was so. No one mentioned it. But it dwelt in the boat, and each man felt it warm him. They were a captain, an oiler, a cook, and a correspondent, and they were friends, friends in a more curiously iron-bound degree than may be common. The hurt captain, lying against the water-jar in the bow, spoke always in a low voice and calmly, but he could never command a more ready and swiftly obedient crew than the motley three of the dingey. It was more than a mere recognition of what was best for the common safety. There was surely in it a quality that was personal and heartfelt. And after this devotion to the commander of the boat there was this comradeship that the correspondent, for instance, who had been taught to be cynical of men, knew even at the time was the best experience of his life. But no one said that it was so. No one mentioned it.

2 “I wish we had a sail,” remarked the captain. “We might try my overcoat on the end of an oar and give you two boys a chance to rest.” So the cook and the correspondent held the mast and spread wide the overcoat. The oiler steered, and the little boat made good way with her new rig. Sometimes the oiler had to scull sharply to keep a sea from breaking into the boat, but otherwise sailing was a success.

3 Meanwhile the lighthouse had been growing slowly larger. It had now almost assumed color, and appeared like a little grey shadow on the sky. The man at the oars could not be prevented from turning his head rather often to try for a glimpse of this little grey shadow.

4 At last, from the top of each wave the men in the tossing boat could see land. Even as the lighthouse was an upright shadow on the sky, this land seemed but a long black shadow on the sea. It certainly was thinner than paper. “We must be about opposite New Smyrna,” said the cook, who had coasted this shore often in schooners. “Captain, by the way, I believe they abandoned that life-saving station there about a year ago.”

5 “Did they?” said the captain. . . .

6 Slowly the land arose from the sea. From a black line it became a line of black and a line of white, trees and sand. Finally, the captain said that he could make out a house on the shore. “That’s the house of refuge, sure,” said the cook. “They’ll see us before long, and come out after us.”

7 The distant lighthouse reared high. “The keeper ought to be able to make us out now, if he’s looking through a glass,” said the captain. “He’ll notify the life-saving people.”

8 “None of those other boats could have got ashore to give word of the wreck,” said the oiler, in a low voice. “Else the lifeboat would be out hunting us.”

9 Slowly and beautifully the land loomed out of the sea. The wind came again. It had veered from the north-east to the south-east. Finally, a new sound struck the ears of the men in the boat. It was the low thunder of the surf on the shore. “We’ll never be able to make the lighthouse now,” said the captain. “Swing her head a little more north, Billie,” said he.

10 “‘A little more north,’ sir,” said the oiler.

11 Whereupon the little boat turned her nose once more down the wind, and all but the oarsman watched the shore grow. Under the influence of this expansion doubt and direful apprehension was leaving the minds of the men. The management of the boat was still most absorbing, but it could not prevent a quiet cheerfulness. In an hour, perhaps, they would be ashore.

What is the theme suggested by the passage?

A. People facing death often develop a false sense of their chances of rescue.

B. People who go through dangerous situations together feel a special bond.

C. People tend to look after their own safety more than others’ in times of trouble.

D. People respect the orders of an authority figure, even if the authority figure is hurt.

To answer this question, ask yourself what is going on in the passage. There are several men in a lifeboat who do not know each other very well. Each is identified only by his job—correspondent, oiler, captain, cook. It is true that the characters seem hopeful of rescue, although it is far from certain, so choice A may seem possible. The men in the boat do seem to respect the injured captain, so choice D may seem like a good choice. Based on the first paragraph of the passage, choice C is not correct because it is clear from the first paragraph that a “brotherhood” based on the need for “common safety” had developed among the people in the boat. The author also refers to them repeatedly as “the men”—a unit. Based on the details in the passage, choice B is the best option.

Plot or Events in a Story

The plot is what happens in a story. The plot is made up of various events that build a story line. In a typical plot, there is a central problem; something needs to be accomplished, or maybe something goes wrong. The story may also provide a resolution: how the problem is resolved or fixed.

The GED® test will ask you questions about the problems facing a character.

Directions: Read the following passage. Then answer the questions.

1 Pat’s house was full of animals. The neighbors called it a zoo. There were the usual pets, a couple of cats and some kittens, an older dog, some goldfish and a parrot. Pat also kept a lizard, a turtle, a spider and a snake indoors. Outside she had a pen full of rabbits.

2 One day Pat’s mother came home and found a mouse in a shoe box. Pat had brought it home from school to keep for the weekend.

3 “That’s it,” her mother said, sounding more upset than Pat had ever heard her. “This zoo has got to go. I want to live in a house where there are more people than animals.”

4 Pat’s mother let her keep the dog and the two cats. Pat had to find a home for the rest of her pets. Pat missed her animal friends. For a while she felt very sad, but Pat was not a person to just sit around and feel sorry for herself. There was a pet hospital a few blocks away. Pat spoke to the veterinarian and asked if she could help out. She offered to clean out the cages and walk the dogs that needed exercise. They were happy to give her the job. Every day after school, before Pat went home to her own pets, she helped the sick animals at the hospital. Pat was happy, the animals were happy and so was her mother.

What was Pat’s problem?

A. She wanted more animals for her zoo.

B. She could not keep the mouse in the box.

C. Her mother was not able to take care of all of the animals.

D. Her mother wanted to find other homes for some of her pets.

To answer this question you need to figure out what Pat’s central problem is. Choice A does not seem to be the problem. There is nothing in the text to suggest that choice B or C is correct either. Choice D is the correct answer. She had to get rid of some pets.

Now that you know what the problem is, you need to find the quotation that supports it.

Which quotation from the story supports the central problem?

A. “Pat’s house was full of animals.”

B. “Outside she had a pen full of rabbits.”

C. “‘This zoo has got to go.’”

D. “Pat was happy, the animals were happy and so was her mother.”

Only choice C is directly related to the problem that Pat faces. Her mother said she didn’t want so many animals. The other choices are details, but they do not support the central problem.

Which quotation from the story supports the resolution?

A. “Pat missed her animal friends.”

B. “For a while she felt very sad.”

C. “There was a pet hospital a few blocks away.”

D. “she helped the sick animals at the hospital.”

To answer this question, first figure out what the resolution is. Then look for the quotation that most closely supports it. Choice D is the only quotation that supports the resolution. The other choices tell details, but do not relate to the resolution.

Characters

One of the most important elements of fiction is the characters in a story. They shape the story and give it meaning. Story characters are often multifaceted and deserve careful study.

There are many ways that an author develops the characters in a story. Authors may describe a character directly by telling what the person is like, or they may prefer to have the reader figure out what the character is like based on the way the character acts and speaks, what others say about the character, and how the character interacts with others.

The GED® test will ask you questions about what words best describe a character. Read the following example and answer the question.

Directions: Read the following text, which is excerpted from Winesburg, Ohio by Sherwood Anderson. Then answer the question.

1 George came down the little incline from the New Willard House at seven o’clock. Tom Willard carried his bag. The son had become taller than the father.

2 On the station platform everyone shook the young man’s hand. More than a dozen people waited about. George was embarrassed. Gertrude Wilmot, a tall thin woman of fifty who worked in the Winesburg post office, came along the station platform. She had never before paid any attention to George. Now she stopped and put out her hand. In two words she voiced what everyone felt. “Good luck,” she said sharply and then turning went on her way.

3 When the train came into the station George felt relieved. He scampered hurriedly aboard. George glanced up and down the car to be sure no one was looking, then took out his pocket-book and counted his money. His mind was occupied with a desire not to appear green. Almost the last words his father had said to him concerned the matter of his behavior when he got to the city. “Be a sharp one,” Tom Willard had said. “Keep your eyes on your money. Be awake. That’s the ticket. Don’t let anyone think you’re a greenhorn.”

4 After George counted his money he looked out of the window and was surprised to see that the train was still in Winesburg.

5 The young man, going out of his town to meet the adventure of life, began to think but he did not think of anything very big or dramatic.

6 He thought of little things—Turk Smollet wheeling boards through the main street of his town in the morning, Butch Wheeler the lamp lighter of Winesburg hurrying through the streets on a summer evening and holding a torch in his hand, Helen White standing by a window in the Winesburg post office and putting a stamp on an envelope.

7 The young man’s mind was carried away by his growing passion for dreams. One looking at him would not have thought him particularly sharp. With the recollection of little things occupying his mind he closed his eyes and leaned back in the car seat. He stayed that way for a long time and when he aroused himself and again looked out of the car window the town of Winesburg had disappeared and his life there had become but a background on which to paint the dreams of his manhood.

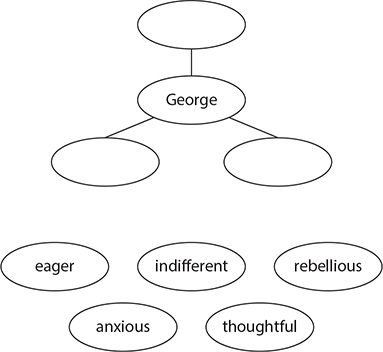

Indicate each word that describes George and belongs in the character web. (Note: On the real GED® test, you will click on the words you choose and “drag” each one into position in the character web.)

To answer this question, check through the various words and see which seem to apply best. George is setting out for a new life, and he seems excited to do so, so the word eager applies. Even though George is somewhat of a dreamer, the word indifferent does not apply; George is alert to the risk of being thought a greenhorn, and he has sharp impressions of life in Winesburg. George does not seem rebellious, but rather traditional, so that word too can be eliminated. He counts his money and doesn’t want to appear green, so you can infer that he is somewhat anxious. Because he thinks about his past and the future, he can also be called thoughtful.

Motivation

When you analyze a character, you will also need to analyze the character’s motivation—the reasons for his or her actions in the story. Sometimes you must infer a character’s motivation by “reading between the lines”; other times the author states it directly.

Directions: Read the following text, which is excerpted from Ragged Dick by Horatio Alger, Jr. Then answer the question.

1 Dick followed the landlady up two narrow staircases, uncarpeted and dirty, to the third landing, where he was ushered into a room about ten feet square. It could not be considered a very desirable apartment. It had once been covered with an oilcloth carpet, but this was now very ragged, and looked worse than none. There was a single bed in the corner, covered with an indiscriminate heap of bed-clothing, rumpled and not overclean. There was a bureau, with the veneering scratched and in some parts stripped off, and a small glass, eight inches by ten, cracked across the middle; also two chairs in rather a disjointed condition. Judging from Dick’s appearance, Mrs. Mooney thought he would turn from it in disdain.

2 It must be remembered that Dick’s past experience had not been of a character to make him fastidious. In comparison with sleeping in a box, or an empty wagon, even this little room seemed comfortable. He decided to hire it if the rent proved reasonable.

Why did Dick decide to rent the apartment?

A. He liked the landlady.

B. It had a good location.

C. He didn’t care about things being clean.

D. It was better than places he stayed before.

The correct answer is choice D. The author of the story explains that to Dick, no matter how cramped the apartment was, it was still better than sleeping in a box or an empty wagon. The other choices are not indicated by the text.

Sometimes you have to infer a motivation. Read the next example and try to figure out Rosedale’s motivation for his actions.

Directions: Read the following text, which is excerpted from The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton. Then answer the question.

1 “My goodness—you can’t go on living here!” Rosedale exclaimed.

2 Lily smiled. “I am not sure that I can; but I have gone over my expenses very carefully, and I rather think I shall be able to manage it.”

3 “Be able to manage it? That’s not what I mean—it’s no place for you!”

4 “It’s what I mean; for I have been out of work for the last week.”

5 “Out of work—out of work! What a way for you to talk! The idea of your having to work—it’s preposterous.” He brought out his sentences in short violent jerks, as though they were forced up from a deep inner crater of indignation. “It’s a farce—a crazy farce,” he repeated, his eyes fixed on the long vista of the room reflected in the glass between the windows.

6 Lily continued to meet his arguments with a smile. “I don’t know why I should regard myself as an exception—” she began.

7 “Because you ARE; that’s why; and your being in a place like this is a damnable outrage. I can’t talk of it calmly.”

8 She had in truth never seen him so shaken out of his usual glibness; and there was something almost moving to her in his inarticulate struggle with his emotions.

9 He rose with a start which left the rocking-chair quivering on its beam ends, and placed himself squarely before her.

10 “Look here, Miss Lily, I’m going to Europe next week: going over to Paris and London for a couple of months—and I can’t leave you like this. I can’t do it. I know it’s none of my business—you’ve let me understand that often enough; but things are worse with you now than they have been before, and you must see that you’ve got to accept help from somebody. You spoke to me the other day about some debt to Trenor. I know what you mean—and I respect you for feeling as you do about it.”

11 A blush of surprise rose to Lily’s pale face, but before she could interrupt him he had continued eagerly: “Well, I’ll lend you the money to pay Trenor; and I won’t—I—see here, don’t take me up till I’ve finished. What I mean is, it’ll be a plain business arrangement, such as one man would make with another. Now, what have you got to say against that?”

Why does Rosedale offer to pay Lily’s debt?

A. He cares about Lily.

B. He wants to show off.

C. He owes Lily some money.

D. He is a good friend of Trenor.

The passage does not provide a clear-cut answer, so you have to make your best guess based on the evidence in the text. According to the passage, Rosedale does not think Lily should be living where she is living because it is not good enough for her. He also doesn’t like the idea of her working. You are also told that he is struggling with his emotions. On the strength of those clues, choice A seems to be the most logical conclusion: Rosedale cares about Lily. The other choices do not fit with the evidence in the passage.

Character Traits

It is important to notice the words an author uses to describe a person’s character traits.

Directions: Read the following text, which is excerpted from The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne. Then answer the questions.

1 The young woman was tall, with a figure of perfect elegance on a large scale. She had dark and abundant hair, so glossy that it threw off the sunshine with a gleam, and a face which, besides being beautiful from regularity of feature and richness of complexion, had the impressiveness belonging to a marked brow and deep black eye. She was lady-like, too, after the manner of the feminine gentility of those days; characterized by a certain state and dignity, rather than by the delicate, evanescent, and indescribable grace, which is now recognized as its indication. And never had Hester Prynne appeared more lady-like, in the antique interpretation of the term, than as she issued from the prison. Those who had before known her, and had expected to behold her dimmed and obscured by a disastrous cloud, were astonished, and even startled, to perceive how her beauty shone out, and made a halo of the misfortune and ignominy in which she was enveloped. It may be true, that, to a sensitive observer, there was something exquisitely painful in it. Her attire, which, indeed, she had wrought for the occasion, in prison, and had modelled much after her own fancy, seemed to express the attitude of her spirit, the desperate recklessness of her mood, by its wild and picturesque peculiarity.

How does the author describe Hester Prynne?

A. uninteresting and dull looking

B. elegant, feminine, and dignified

C. flirtatious

D. timid

Choice B is the correct answer. The author states directly that Hester was “a figure of perfect elegance,” “lady-like [. . .] after the manner of the feminine gentility of those days,” and “characterized by a certain state and dignity.”

In this case, the author tells you specifically about a person’s character traits. In other cases, however, the author may tell you only how a person looks or what the person says or does, and you will have to interpret those hints in order to infer what the person thinks or feels.

Directions: Read the following text, which is excerpted from Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis. Then answer the questions.

1 His name was George F. Babbitt. He was forty-six years old now, in April, 1920, and he made nothing in particular, neither butter nor shoes nor poetry, but he was nimble in the calling of selling houses for more than people could afford to pay. . . .

2 He looked blurrily out at the yard. It delighted him, as always; it was the neat yard of a successful business man of Zenith, that is, it was perfection, and made him also perfect. He regarded the corrugated iron garage. For the three-hundred-and-sixty-fifth time in a year he reflected, “No class to that tin shack. Have to build me a frame garage. But by golly it’s the only thing on the place that isn’t up-to-date!” While he stared he thought of a community garage for his acreage development, Glen Oriole. He stopped puffing and jiggling. His arms were akimbo. His petulant, sleep-swollen face was set in harder lines. He suddenly seemed capable, an official, a man to contrive, to direct, to get things done.

Which excerpt from the text suggests that George Babbitt is a materialistic person?

A. “he made nothing in particular, neither butter nor shoes nor poetry”

B. “His petulant, sleep-swollen face was set in harder lines.”

C. “It delighted him . . . it was perfection, and made him also perfect.”

D. “He suddenly seemed capable, an official, a man to contrive, to direct, to get things done.”

From the passage, it is clear that George Babbitt sells real estate. In this passage, we only get a short glimpse of him, but two things become apparent: he is a middle-aged man who shows his age somewhat (with his “jiggling” and “sleep-swollen face”). The author seems to implicitly criticize Babbitt’s profession, noting he “was nimble in the calling of selling houses for more than people could afford to pay.” About half of the passage is about how Babbitt looks, and the other half is about what he does and says. He actually does not do much but look over his property as he wakes up, but notice how he reacts to his home, his garage, and his yard. It is clear that he feels these possessions are important parts of how he sees himself. The author is explicit, in fact, in telling the reader that Babbitt adores his yard: “It delighted him, as always; it was the neat yard of a successful business man of Zenith, that is, it was perfection, and made him also perfect.” Someone who values physical possession excessively is considered materialistic. Someone who feels his yard or garage can make him a “perfect” person is materialistic, so choice C is the best option.

Interaction Between Characters

Characters in fiction interact with each other, and when they do they reveal something about themselves and the other characters. Also, the way in which characters with different traits interact and react to each other can be what triggers or determines the events of the story. It is important to watch for the ways that characters in fiction interact with each other.

Directions: Read the following text, which is excerpted from The Fate of Man by Mikhail Sholokhov. Then answer the question.

1 After a year I came back from Kuban, sold my house and went to Voronezh. First I worked as a carpenter, then I went to a factory and learned to be a mechanic. Soon I got married. My wife had been raised in a children’s home. She was an orphan. Yes, I lucked out there! Good-tempered, cheerful, always anxious to please. And smart she was, too. No comparison with me. She had known real trouble since she was a kid—maybe that affected her character. Just looking at her from the side, she wasn’t all that striking. But, you see, I wasn’t looking at her from the side, I was looking at her full face. And for me there was no more beautiful woman in the whole world, and there never will be.

2 I’d come home from work tired and ill-tempered. But she’d never fling your rudeness back at you. She’d be so gentle and quiet, couldn’t do enough for you, always trying to get you a bit of somethin’ nice, even when there wasn’t enough to go around. It made your heart lighter just to look at her, and after a while you’d put your arm around her and say: “Sorry I was rude to you, Irina my love, I had a rotten day at work today.” And again there’d be peace between us, and my mind would be at rest. And you know what that means to your world, my friend? In the morning I’d be out of bed like a shot and off to the factory, and any job I laid hands on would go smooth as clockwork.

What effect did Irina’s character have on her husband?

A. She pushed him to work harder and get ahead.

B. Her kindness brought him out of his bad moods.

C. He felt sorry for her and was never unkind to her.

D. He was as anxious to please her as she was to please him.

Irina’s effect on her husband was that she helped him overcome his bad mood. Choice B is the correct answer. The text clearly shows this with several examples.

Setting

The setting of a story is where and when it takes place. Sometimes the author does not tell you the setting in so many words. You must figure it out. Read the next few lines and figure out the setting.

The sand had gotten in his bathing suit and in his hair. The hot sun was burning his skin. Sonny was tired, but he did not wish to leave. The sound of the waves was like beautiful music to Sonny. His mother said that they had to go home for lunch, and then go shopping for dinner.

The hot sun, the sand, and the waves all show Sonny was at the beach. You can also guess that it is the middle of the day. The story says that Sonny had to go home for lunch. These five sentences tell you where and when the story is set.

Setting often has a strong influence on a story. It helps determine the plot and define the characters.

Directions: Read the following text, which is excerpted from To Build a Fire by Jack London. Then answer the question.

1 The man flung a look back along the way he had come. The Yukon lay a mile wide and hidden under three feet of ice. On top of this ice were as many feet of snow. It was all pure white, rolling in gentle undulations where the ice-jams of the freeze-up had formed. North and south, as far as his eye could see, it was unbroken white, save for a dark hairline that curved and twisted from around the spruce-covered island to the south, and that curved and twisted away into the north, where it disappeared behind another spruce-covered island. This dark hairline was the trail—the main trail—that led south five hundred miles to the Chilcoot Pass, Dyea, and salt water; and that led north seventy miles to Dawson, and still on to the north a thousand miles to Nulato, and finally to St. Michael on Bering Sea, a thousand miles and a half thousand more.

2 But all this—the mysterious, far reaching hairline trail, the absence of sun from the sky, the tremendous cold, and the strangeness and weirdness of it all—made no impression on the man. It was not because he was long used to it. He was a newcomer in the land, a cheechako, and this was his first winter. The trouble with him was that he was without imagination. He was quick and alert in the things of life, but only in things, not in the significances. Fifty degrees below zero meant eighty-odd degrees of frost. Such fact impressed him as being cold and uncomfortable, and that was all. It did not lead him to meditate on his frailty as a creature of temperature, and upon man’s frailty in general, able only to live within certain narrow limits of heat and cold; and from there on it did not lead him to the conjectural field of immortality and man’s place in the universe. Fifty degrees below zero stood for a bite of frost that hurt and that must be guarded against by the use of mittens, ear flaps, warm moccasins, and thick socks. Fifty degrees below zero was to him just precisely fifty degrees below zero. That there should be anything more to it than that was a thought that never entered his head.

How does the setting influence the story?

A. It explains why the man is alone.

B. It tells when the story takes place.

C. It helps to define the man’s character.

D. It determines what will happen next.

When reading this passage, you almost have the feeling that the setting is another character. The interaction between the setting and the man gives the author a way to vividly define the man’s character (choice C). Choice A is incorrect. There is nothing in the setting that explains why the man is alone. Choice B is also incorrect. Nothing in the setting tells you when the story takes place. Choice D is also incorrect because the setting provides no hint about what will happen next.

Character and Narrator Viewpoint

The characters and the narrator (if there is a narrator) all have a point of view. Each one sees the story from a different perspective, and how they feel about what is happening influences the plot. It is up to the reader to determine what point of view characters have based on what they say and do. Read the following passage and think about the point of view of each character.

Directions: Read the following excerpt from Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, by Mark Twain. Then answer the question.

1 The Widow Douglas she took me for her son, and allowed she would sivilize me; but it was rough living in the house all the time, considering how dismal regular and decent the widow was in all her ways; and so when I couldn’t stand it no longer I lit out. I got into my old rags and my sugar-hogshead again, and was free and satisfied. But Tom Sawyer he hunted me up and said he was going to start a band of robbers, and I might join if I would go back to the widow and be respectable. So I went back.

2 The widow she cried over me, and called me a poor lost lamb, and she called me a lot of other names, too, but she never meant no harm by it. She put me in them new clothes again, and I couldn’t do nothing but sweat and sweat, and feel all cramped up. Well, then, the old thing commenced again. The widow rung a bell for supper, and you had to come to time. When you got to the table you couldn’t go right to eating, but you had to wait for the widow to tuck down her head and grumble a little over the victuals, though there warn’t really anything the matter with them,—that is, nothing only everything was cooked by itself. In a barrel of odds and ends it is different; things get mixed up, and the juice kind of swaps around, and the things go better.

What is the point of view of the speaker in the passage?

A. He is a lonely orphan and craves adult attention and care.

B. He is a natural risk-taker who enjoys breaking the law.

C. He wants to live his life by his own rules, not the rules of others.

D. He feels guilty that he cannot live up to the expectations of the widow.

Hints in the passage indicate that the speaker (who is Huckleberry Finn, by the way) is indeed an orphan, and probably fairly young. Choice A might seem appealing. There is a mention of a friend wanting him to join a “band of robbers,” so choice B might seem like a possibility. Huckleberry does seem to respect the Widow Douglas, so choice D might be an option. However, if you look at everything Huck says, it is evident that while he thinks the Widow Douglas is a good person, he is not really interested in her mission to “sivilize” him and he chafes at her attempts. He even runs away, and is only lured back by his friend’s offer to start a band of robbers (which seems most likely to be a boyish game instead of a criminal plan). All the evidence in the passage points to Huck wanting to be “free” to do as he pleases. Choice C, then, is the best answer.

Directions: Read the following text, which is excerpted from The Sheik by Edith Hull. Then answer the question.

1 The voice seemed to come from the dark shadows at the end of the garden. The singer sang slowly, his voice lingering caressingly on the words; the last verse dying away softly and clearly, almost imperceptibly fading into silence.

2 For a moment there was utter stillness; then Diana lay back with a little sigh. “The Kashmiri Song. It makes me think of India. I heard a man sing it in Kashmere last year, but not like that. What a wonderful voice!”

3 Arbuthnot looked at her curiously, surprised at the sudden ring of interest in her tone, and the sudden animation of her face.

4 “You say you have no emotion in your nature, and yet that unknown man’s singing has stirred you deeply. How do you reconcile the two?” he asked, almost angrily.

5 “Is an appreciation of the beautiful emotion?” she challenged, with uplifted eyes. “Surely not. Music, art, nature, everything beautiful appeals to me. But there is nothing emotional in that. It is only that I prefer beautiful things to ugly ones. For that reason even pretty clothes appeal to me,” she added, laughing.

6 “You are the best-dressed woman in Biskra,” he acceded. “But is not that a concession to the womanly feelings that you despise?”

7 “Not at all. To take an interest in one’s clothes is not an exclusively feminine vice. I like pretty dresses. I admit to spending some time in thinking of colour schemes to go with my horrible hair, but I assure you that my dressmaker has an easier life than my brother’s tailor.”

8 She sat silent, hoping that the singer might not have gone, but there was no sound except a cicada chirping near her. She swung round in her chair, looking in the direction from which it came. “Listen to him. Jolly little chap! They are the first things I listen for when I get to Port Said. They mean the East to me.”

9 “Maddening little beasts!” said Arbuthnot irritably.

10 “They are going to be very friendly little beasts to me during the next four weeks. . . . . You don’t know what this trip means to me. I like wild places. The happiest times of my life have been spent camping in America and India, and I have always wanted the desert more than either of them. It is going to be a month of pure joy. I am going to be enormously happy.”

What is Diana’s viewpoint toward the desert?

A. She is bored by it.

B. She is fearful of it.

C. She thinks it is ugly.

D. She finds it exciting.

Choice D is the correct answer. This is what she feels toward the East and the desert. Paragraph 3 gives you some clues by saying that she had interest in her tone and that her face became animated.

PRACTICE

Literary Texts

Directions: Read the following text, which is excerpted from Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain. Then answer the questions that follow.

1 “TOM! Where are you?”

2 No answer was forthcoming.

3 “TOM! Come here!”

4 Still no answer was heard.

5 “What’s gone with that boy, I wonder? You TOM!”

6 No answer was heard yet again.

7 The woman pulled her spectacles down and looked over them about the room; then she put them up and looked out under them. She seldom or never looked THROUGH them for so small a thing as a boy; they were her best pair, the pride of her heart, and were built for “style,” not service—she could have seen through a pair of stove-lids just as well; she looked perplexed for a moment, and then said, not fiercely, but still loud enough for the furniture to hear:

8 “Well, I if you don’t come right away I’ll—”

9 She did not finish, for by this time she was bending down and checking under the bed with the broom, and so she needed breath to punctuate her search; she didn’t find anything but the cat.

10 She went to the open door and stood in it and looked out among the tomato vines and weeds in the garden: no Tom there. So she lifted up her voice at an angle calculated for distance and shouted:

11 “Y-o-u-u TOM, answer me at once!”

12 There was a slight noise behind her and she turned just in time to seize a small boy by the slack of his shirt and stop his flight.

13 “There! I might ‘a’ thought of that closet. What you been doing in there?”

14 “Nothing.”

15 “Nothing! Look at your hands and look at your mouth; what IS that stuff?”

16 The lad said nothing; instead he looked down at his feet.

17 “Well, I know; it’s jam—that’s what it is—and you know too. Forty times I’ve said if you didn’t let that jam alone you would be punished.”

18 “I’m sorry, Aunt. I couldn’t help myself.”

19 The threat of punishment hovered in the air—the peril was intense—

20 Then quite suddenly Tom spoke in a voice filled with deep concern. “My! Watch out; look behind you, aunt!”

21 His aunt whirled round, and snatched her skirts out of danger and just in that instant the lad fled, scrambling up the high board-fence, and disappearing over it, far out of sight of his aunt.

22 His aunt Polly stood surprised a moment, and then broke into a gentle laugh.

23 “Hang the boy, can’t I never learn anything? Ain’t he played me tricks enough like that for me to be looking out for him by this time? But old fools is the biggest fools there is. Can’t learn an old dog new tricks, as the saying is. But my goodness, he never plays them alike, two days, and how is a body to know what’s coming? He ’pears to know just how long he can torment me before I get my dander up, and he knows if he can make out to put me off for a minute or make me laugh, it’s all down again. He’s sure is mischievous, but laws-a-me; he’s my own sister’s boy, and I ain’t got the heart to really punish him, somehow. Every time I let him off, my conscience does hurt me so, and every time I punish him my old heart most breaks. Well-a-well, man that is born of woman is of few days and full of trouble, and I reckon it’s so.”

1. Which quotation from the text best supports the theme of the story?

A. “The woman pulled her spectacles down and looked over them about the room; then she put them up and looked out under them.”

B. “She went to the open door and stood in it and looked out among the tomato vines and weeds in the garden: no Tom there.”

C. “There was a slight noise behind her and she turned just in time to seize a small boy by the slack of his shirt and stop his flight.”

D. “He ’pears to know just how long he can torment me before I get my dander up, and he knows if he can make out to put me off for a minute or make me laugh, it’s all down again.”

2. What is Tom’s viewpoint?

A. He dislikes his aunt.

B. He enjoys annoying his aunt.

C. He wants to change the way that he acts.

D. He thinks that his aunt should be stricter.

3. Which excerpt supports the idea that Tom is someone who can move very quickly?

A. There was a slight noise behind her and she turned just in time to seize a small boy by the slack of his shirt and stop his flight.

B. “I’m sorry, Aunt. I couldn’t help myself.”

C. Then quite suddenly Tom spoke in a voice filled with deep concern. “My! Watch out; look behind you, aunt!”

D. His aunt whirled round, and snatched her skirts out of danger and just in that instant the lad fled, scrambling up the high board-fence, and disappearing over it, far out of sight of his aunt.

4. Why does Aunt Polly feel badly about punishing Tom?

A. He is very young.

B. He is her sister’s son.

C. He cries a lot when he is punished.

D. He does not understand right from wrong.

Directions: Read the following text, which is excerpted from Mr. Travers’ First Hunt by Richard Harding Davis. Then answer the questions that follow.

1 Young Travers, who had been engaged to a girl down on Long Island, only met her father and brother a few weeks before the day set for the wedding. The father and son talked about horses all day and until one in the morning, for they owned fast thoroughbreds, and entered them at race-tracks. Old Mr. Paddock, the father of the girl to whom Travers was engaged, had often said that when a young man asked him for his daughter’s hand he would ask him in return, not if he had lived straight, but if he could ride straight.

2 Travers was invited to their place in the fall when the fox-hunting season opened, and spent the evening most pleasantly and satisfactorily with his fiancée in a corner of the drawing-room.

3 But as soon as the women had gone, young Paddock joined him and said, “You ride, of course?” Travers had never ridden; but he had been prompted how to answer by Miss Paddock, and so said there was nothing he liked better.

4 “That’s good,” said Paddock. “I’ll give you Monster tomorrow morning at the meet. He is a bit nasty at the start of the season; and ever since he killed Wallis, the second groom, last year, none of us care much to ride him. But you can manage him, no doubt.”

5 Mr. Travers dreamed that night of taking large, desperate leaps into space on a wild horse that snorted forth flames, and that rose at solid stone walls as though they were haystacks.

6 He came downstairs the next morning looking very miserable indeed. Monster had been taken to the place where they were to meet, and Travers viewed him on his arrival there with a sickening sense of fear as he saw him pulling three grooms off their feet.

7 Travers decided that he would stay with his feet on solid earth just as long as he could, and when the hounds were sent off and the rest had started at a gallop, he waited until they were all well away. Then he scrambled up onto the saddle and the next instant he was off after the others, with a feeling that he was on a locomotive that was jumping the ties. Monster had passed the other horses in less than five minutes.

8 Travers had taken hold of the saddle with his left hand to keep himself down, and sawed and swayed on the reins with his right. He shut his eyes whenever Monster jumped, and never knew how he happened to stick on; but he did stick on, and was so far ahead that no one could see in the misty morning just how badly he rode. As it was, for daring and speed he led the field.

9 There was a broad stream in front of him, and a hill just on its other side. No one had ever tried to take this at a jump. It was considered more of a swim than anything else, and the hunters always crossed it by the bridge. Travers saw the bridge and tried to jerk Monster’s head in that direction; but Monster kept right on as straight as an express train over the prairie.

10 Travers could only gasp and shut his eyes. He remembered the fate of the second groom and shivered. Then the horse rose like a rocket, lifting Travers so high in the air that he thought Monster would never come down again; but he did come down, on the opposite side of the stream. The next instant he was up and over the hill, and had stopped panting in the very center of the pack of hounds that were snarling and snapping around the fox.

11 And then Travers hastily fumbled for his cigar case, and when the others came pounding up over the bridge and around the hill, they saw him seated nonchalantly on his saddle, puffing critically at a cigar, and giving Monster patronizing pats on the head.

12 “My dear girl,” said old Mr. Paddock to his daughter as they rode back, “if you love that young man of yours and want to keep him, make him promise to give up riding. A more reckless and more brilliant horseman I have never seen. He took that jump at that stream like a centaur. But he will break his neck sooner or later, and he ought to be stopped.”

13 Young Paddock was so delighted with his prospective brother-in-law’s great riding that that night in the smoking-room he made him a present of Monster before all the men.

14 “No,” said Travers, gloomily, “I can’t take him. Your sister has asked me to give up what is dearer to me than anything next to herself, and that is my riding. She has asked me to promise never to ride again, and I have given my word.”

15 A chorus of sympathy rose from the men.

16 “Yes, I know,” said Travers to her brother, “it is rough, but it just shows what sacrifices a man will make for the woman he loves.”

5. Which of the following best describes Travers’ problem?

A. He is fearful of asking young Paddock how to ride.

B. He worries that his fiancée does not really care for him.

C. He wants to impress his fiancée’s family, but he is afraid.

D. He wants to impress young Paddock, but he does not know how.

6. How does Travers give the impression that he is an excellent rider?

A. by getting Monster to do several jumps

B. by showing that he is skilled in handling the horse

C. by bragging a lot about his riding ability after the hunt

D. by managing to stay on Monster as the horse goes wildly onward

7. Which of the following best explains why Travers did not take the bridge over the stream?

A. He preferred to jump over it.

B. His fiancée warned him not to.

C. He couldn’t get Monster to go over to it.

D. He wanted to show off his courage and skill.

8. In paragraph 4, what is one probable reason that young Paddock chose Monster for Travers to ride?

A. He wants to test Travers.

B. He wants to upset his sister.

C. He wants to please Travers.

D. He thinks Travers deserves the best horse.

Directions: Read the following text, which is excerpted from Hearts and Hands by O. Henry. Then answer the questions that follow.

1 At Denver there was an influx of passengers into the coaches on the eastbound express. In one coach there sat a very pretty young woman dressed in elegant taste and surrounded by all the luxurious comforts of an experienced traveler. Among the newcomers were two young men, one of handsome presence with a bold, frank look and manner, the other a ruffled, glum-faced person, heavily built and roughly dressed. The two were handcuffed together.

2 As they passed down the aisle of the coach, the only vacant seat offered was a reversed one facing the attractive young woman. Here the linked couple seated themselves. The young woman’s glance fell upon them with a distant, swift disinterest. Then with a lovely smile brightening her face and a tender pink coloring her rounded cheeks, she held out a little gray-gloved hand. When she spoke her voice, full, sweet, and deliberate, proclaimed that its owner was accustomed to speak and be heard.

3 “Well, Mr. Easton, if you will make me speak first, I suppose I must. Don’t you ever recognize old friends when you meet them in the West?”

4 The younger man roused himself sharply at the sound of her voice, seemed to struggle with a slight embarrassment which he threw off instantly, and then clasped her fingers with his left hand.

5 “It’s Miss Fairchild,” he said, with a smile. “I’ll ask you to excuse the other hand; it’s otherwise engaged just at present.”

6 He slightly raised his right hand, bound at the wrist by the shining “bracelet” to the left one of his companion. The glad look in the girl’s eyes slowly changed to a bewildered horror. The glow faded from her cheeks. Her lips parted in a vague distress. Easton, with a little laugh, as if amused, was about to speak again, when the other man interrupted him. The glum-faced man had been watching the girl’s countenance with veiled glances from his keen, shrewd eyes.

7 “You’ll excuse me for speaking, miss, but I see you’re acquainted with the marshal here. If you’ll ask him to speak a word for me when we get to the pen he’ll do it, and it’ll make things easier for me there. He’s taking me to Leavenworth prison. It’s seven years for counterfeiting.”

8 “Oh!” said the girl, with a deep breath and returning color. “So that is what you are doing out here? A marshal!”

9 “My dear Miss Fairchild,” said Easton, calmly, “I had to do something. Money has a way of taking wings unto itself, and you know it takes money to keep in step with our crowd in Washington. I saw this opening in the West, and—well, a marshalship isn’t quite as high a position as that of ambassador, but—”

10 “The ambassador,” said the girl, warmly, “doesn’t call any more. He needn’t ever have done so. You ought to know that. And so now you are one of these dashing Western heroes, and you ride and shoot and go into all kinds of dangers. That’s different from the Washington life. You have been missed from the old crowd.”

11 The girl’s eyes, fascinated, went back, widening a little, to rest upon the glittering handcuffs.

12 “Don’t you worry about them, miss,” said the other man. “All marshals handcuff themselves to their prisoners to keep them from getting away.”

13 “Will we see you again soon in Washington?” asked the girl.

14 “Not soon, I think,” said Easton. “My butterfly days are over, I fear.”

15 “I love the West,” said the girl. She looked out the car window. She began to speak truly and simply, without the gloss of style and manner: “Mamma and I spent the summer in Denver. She went home a week ago, because Father was slightly ill. I could live and be happy in the West. I think the air here agrees with me. Money isn’t everything. But people always misunderstand things and remain stupid—”

16 “Say, Mr. Marshal,” growled the glum-faced man. “This isn’t quite fair. I haven’t had a smoke all day. Haven’t you talked long enough? Take me in the smoker now, won’t you? I’m half dead for a pipe.”

17 The bound travelers rose to their feet, Easton with the same slow smile on his face.

18 “I can’t deny a petition for tobacco,” he said lightly. “It’s the one friend of the unfortunate. Good-bye, Miss Fairchild. Duty calls, you know.” He held out his hand for a farewell.

19 “It’s too bad you are not going East,” she said, reclothing herself with manner and style. “But you must go on to Leavenworth, I suppose?”

20 “Yes,” said Easton, “I must go on to Leavenworth.”

21 The two men sidled down the aisle into the smoker.

22 The two passengers in a seat nearby had heard most of the conversation. Said one of them: “That marshal’s a good sort of chap. Some of these Western fellows are all right.”

23 “Pretty young to hold an office like that, isn’t he?” asked the other.

24 “Young!” exclaimed the first speaker, “why—Oh, didn’t you catch on? Say—did you ever know an officer to handcuff a prisoner to his right hand?”

9. How does the setting influence the story?

A. The train allows the characters to talk freely.

B. The train provides a means for a chance meeting.

C. The train helps the characters focus on their problems.

D. The train helps the marshal understand what is going on.

10. Which is the most likely description of Easton’s relationship to the ambassador?

A. He left Washington because he fought with him.

B. He wanted to become ambassador instead of him.

C. He was a good friend of the ambassador and misses him.

D. He was jealous about his seeing Miss Fairchild in Washington.

11. Which best describes Miss Fairchild’s initial reaction upon seeing Easton with handcuffs?

A. She was angry.

B. She was horrified.

C. She was uninterested.

D. She thought it was funny.

12. What is the marshal’s viewpoint toward Easton?

A. He is worried that Easton will try to escape.

B. He wants to spare Easton from an embarrassment.

C. He feels that Easton should tell Miss Fairchild the truth.

D. He thinks Easton should have been punished more severely.