CHAPTER 13

The Air Force Recovers from Vietnam

“Who understands the secret of the reaping of the grain?... Or why we all must die a bit before we grow again?”

—The Fantasticks

THAT IS THE WAY IT WAS for the United States Air Force during the middle Cold War years. In the 1950s, America’s fighter jocks dominated the skies over Korea. They ran up a ten-to-one score against the offending North Korean MiGs. Forty years later the Yanks again ruled the skies. USAF pilots popped laser and video-guided bombs down the air shafts of Iraqi intelligence centers with impunity. But in between lay winter’s laboring pain. We all had to die a bit, in Vietnam, before we grew again.

A TRAIN WRECK IN THE SKY

Americans have come to accept the loss of a dozen or so aircraft during any given modern-day struggle. During the war in Korea, the UN Command (principally the U.S.) lost 139 aircraft. But during the years of its involvement in Southeast Asia (1962-73), the losses of the United States Air Force alone totalled 2,257 aircraft. The Navy, Marines, and Army suffered proportional losses.

Eighty-three percent of the USAF combat losses were to ground fire; that is, antiaircraft artillery and small arms. Only 6 percent were lost to SAMs. The pilots of most aircraft hit by SAMs never saw the missiles coming, for if a pilot saw a SAM, he could usually outmaneuver it.

Only 4 percent of the losses came as a result of air-to-air combat. The air-to-air exchange ratio was only 1.85 to one in favor of the U.S. It was only 1.21 to one against the most common airborne enemy, MiG-21s. In comparing these kill ratios to other wars, however, one must bear in mind that in the skies over Vietnam, the U.S. combatants were often fighter-bombers heavily laden with ground-attack ordnance en route to other targets. Over half of the losers in air-to-air combat never knew they were under attack until they were hit. How could all of this have happened?

In the aftermath of Korea, Eisenhower’s “new look” placed the nation’s bets on nuclear deterrence. There was to be no buildup for conventional war. It was assumed that if war broke out in Europe, it would soon go nuclear. Aircraft such as the F-100 and F-105 were developed to deliver tactical nuclear weapons onto enemy positions at low altitudes and high speed. The F-102 and F-104 were developed to intercept Soviet bombers. Fighting in the sky was neglected and support of troops on the ground was ignored. Attacks on enemy infrastructure were to be effected with nukes, so repeated sorties would not be needed. Any ground war in Asia was thought to be foolish and was assumed away. As a result, a well-meant but misguided allocation of resources soon left the U.S. Air Force focused on nuclear war, to the exclusion of its other duties.

The early 1960s brought a fresh and more realistic look at nuclear matters. The Kennedy administration recognized that the Soviet Union was a major thermonuclear power, and that the USSR would soon have the ability to deliver nuclear weapons to U.S. soil. Thus, any American use of nukes could only trigger a broader exchange that would be lethal to both sides. “Assured Destruction” was the term used by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara to describe our planned ability to respond decisively, even in the event of a surprise nuclear attack. Pundits quickly amended this expression to Mutual Assured Destruction, with the acronym, MAD, reflecting their view of McNamara’s policies. The Kennedy administration, awash with youthful exuberance, turned to a theory of Flexible Response to deal with the threat of Soviet nuclear attacks, to an enthusiasm for Special Forces to deal with conventional threats, and to systems analysis to deal with the ever-recurrent budget crunch.

One casualty of fiscal analysis was the C-5, a large transport aircraft that fell victim to the concept of “package procurement.” Under this theory, a contractor was to develop and produce a fleet of aircraft at a fixed price, set in advance. Lockheed accepted a fixed price contract for the package procurement of the C-5, a radically new concept in air transport. When the design was complete, the aircraft, on paper, was overweight. Lockheed cut back on wing structure to meet the weight specification, but as a result, wing life was shortened by over 75 percent. The ultimate replacement of the C-5’s wings cost $1 billion and untold grief with the U.S. Congress.

Another marginal idea was the “one size fits all” approach to aircraft procurement. This led to the TFX disaster. This tactical fighter, later to be known as the F-111, was to be a common aircraft for Navy and Air Force use, but operating and landing an aircraft at sea is very different from flying and fighting over mountainous terrain. The result was a difficult aircraft, initially lethal to its crews. The Navy never bought any, but in time the F-111 became popular with the Air Force as a medium-range bomber with excellent low-altitude penetration abilities. As an EF-111, it also served well as an electronics warfare platform. When it was time to go to war in Vietnam, however, the Air Force had to turn to a Navy airplane, the F-4, if it was to have any air-to-air capability at all. It purchased 2,712 of those aircraft during that war.

With the advent of the Johnson administration and the escalation of the war in Vietnam, “Gradualism” was adopted as a strategy. Inexperienced civilian leadership and a few misguided generals believed that an enemy’s actions could be controlled by the application of force, increased gradually so as to minimize the risk of Soviet or Chinese intervention. U.S. leaders felt gradualism was important, given the lessons of Korea and the dangers of the nuclear threshold; China had just entered the nuclear club. Under this theory, each U.S. air raid was to send a message. Attacks on North Vietnam were punctuated by nine ceasefires and ten bombing halts, each followed by pleas for negotiations, all ignored by the North Vietnamese.

Targets were picked or withheld by the President, his Secretary of Defense, National Security Adviser, and Joint Chiefs chairman at White House working luncheons. Those targeting decisions were not made by operational commanders in the field. The resulting air war abandoned the principles of surprise, massed force, and timely execution, all fundamental to military success.

The foolishness of these policies became obvious to Lieutenant Joe Ralston one day in 1967 as he flew his F-105 into North Vietnam, en route to targets in Route Package 6B. Looking down, he saw enemy MiG-21s taxiing for take off from the Phuc Yen airfield. In a few moments they would be airborne; a few moments after that, they would be trying to kill his buddies in the following wave of F-105s. At that moment those MiG-21s were very vulnerable, taxiing ducks. In earlier wars,Ralston and his wingman would have pounced, destroying a whole flight of MiG-21s on the ground, but on that day Phuc Yen was not an approved target. Those MiGs could prepare for battle unmolested. The aircraft themselves were not to be attacked until they were airborne. Ralston had to fly on; the pilots in the next wave paid the price.

A CHANGING OF THE GUARD

As the war in Vietnam dragged on, the morale of many sent there to fight sank through the floor. The men who flew executed their missions with pride, but many were resentful of Washington’s naiveté, and the U.S. Air Force was learning lessons that would change its entire culture.

This process of recovery and change started as the sixties ended. The Nixon and Ford administrations brought a new generation of civilian technocrats to the Pentagon, men and women willing to listen to the lessons learned in Vietnam, willing to bring a political consistency to their work, and willing to promote those with serious Vietnam experience into positions of responsibility. My predecessor as Secretary of the Air Force, myself, and the Director of Defense Research and Engineering in the succeeding Carter administration, were the civilian leaders who presided over this transition from the Air Force of Vietnam to the powerhouse of Desert Storm. Our Secretaries of Defense—James Schlesinger, Donald Rumsfeld, and Harold Brown—provided the leadership; thousands of men and women in the ranks did the hard work.

The Pentagon is a surprisingly efficient and well-run enterprise, even though its basic mission—war—is an inherently wasteful product that no one wants. The way it works is, the service secretaries, in partnership with their service chiefs of staff, build the forces. They recruit and train people, develop and purchase equipment, see to the maintenance of that equipment throughout its life cycle, and manage the bases and network of benefits that support the whole system. The service secretaries seek appropriations from Congress and oversee the prudent expenditure of those funds. As such, they are the primary civilian advocates for their services’ case to the American public. The secretaries manage selection, promotion, and assignment of most general officers, all of whom serve at the pleasure of the President with the advice and consent of the Senate. They do these things in accordance with policies laid down by the Secretary of Defense and his under and assistant secretaries. The Director of Defense Research and Engineering oversees the military investment in cutting-edge technology. When their job is done and the forces assembled, the service secretaries and their chiefs then turn the forces they have developed over to the Secretary of Defense. The services do not run wars; the Secretary of Defense does that, deploying forces and operating them through the unified theater commanders as directed by the President.

As America’s involvement in Vietnam drew to a close, a most remarkable technocrat took charge as Secretary of the Air Force. John McLucas, fifty-two at the time, had a strong background in military electronics and government service. In 1969 he came to the Pentagon to serve as Undersecretary of the Air Force and Director of the National Reconnaissance Office. McLucas watched the end of the war in Vietnam from the front row, absorbing the lessons of that conflict at every turn. In July 1973 he became the tenth Secretary of the Air Force.

McLucas led the Air Force away from the mentality of package procurement and into an era of prototypes. “Fly before you buy” became his watchword. He guided the Air Force’s transition to post-Vietnam tactical aircraft and supported those who were trying to apply the lessons learned in that war. But despite these achievements, John McLucas’s Air Force career was cut short, and mine was created, by the President’s decision to send him off to run the Federal Aviation Administration.

At the time, I was serving as Director of Telecommunications for the Secretary of Defense. As McLucas left, I was tapped to succeed him, confirmed by the U.S. Senate without much trouble and, on January 2, 1976, sworn in as the eleventh Secretary of the Air Force. I remained in office through the end of the Ford administration and beyond. President-elect Jimmy Carter designated Harold Brown to be his Secretary of Defense. Brown, in turn, asked that I stay in place through the first hundred days of the new administration. I did so, overseeing the transition budget and the reassignment of most of the Air Force four-star general officers to their Carter-era responsibilities.

Secretary Brown chose Bill Perry to serve as his Director of Defense Research and Engineering. Perry had founded and run an electronics intelligence firm in Silicon Valley and was attuned to the possibilities of smart munitions. The nation owes its greatest thanks to Brown and Perry for pursuing those possibilities and for initiating key developments in the area of stealthy aircraft.

In his final year in office, President Carter came to appreciate the perfidy of the Soviet leadership. He proposed a defense budget, shaped by Brown and Perry, that laid the technical groundwork for the Reagan era to follow. From 1973 through 1980, the years of the McLucas/ Reed/Perry tenure, the lessons of Vietnam were absorbed by an Air Force eager to enter a new era.

LESSONS LEARNED

The first lesson learned in the skies over Vietnam, one that must never be forgotten, is that the primary mission of an air force is to fly and fight in the sky. If it cannot do that, if it cannot gain control of the skies over the battlefield and over the enemy’s infrastructure, then it has failed, for it will never be able to move on to the destruction of those enemy assets.

To gain control of the skies, an air force needs an air superiority fighter. Such an aircraft must be fast and highly maneuverable. It must be hard to see, by the human eye, radar, or infrared sensors. The pilot must have near perfect visual access to the skies around him and must have a radar that will let him look and shoot down as well as up, to discriminate a moving target from the background earth. He must be armed with air-to-air missiles that are as maneuverable as the enemy’s aircraft, and he must have good old-fashioned guns at his disposal. Last, but not least, an air superiority fighter must be affordable, for numbers do count. An air force that is to prevail must put a large number of its aircraft into the fight. The F-4 failed most of these criteria. It was a jack-of-all-trades, master of none. Much larger than its MiG-21 adversary, the F-4 was made even more visible by its smoky engine.

The Operational Requirement for the needed new fighter was written and approved by the Air Staff in the autumn of 1965, but it took two years for the bureaucracy to settle on the specifics, sort out the tradeoffs, and forecast the technology. Two more years passed until McDonnell Douglas was selected as the contractor to build this air superiority fighter, now known as the F-15.

In one of his first moves as Secretary of the Air Force, John McLucas approved the F-15 for production. It first flew at Edwards Air Force Base in July 1972, and the first deliveries began in November 1974. The first squadron went operational in September 1975, half a year after the last American was evacuated from the rooftops of Saigon.

Two new technology Pratt & Whitney F-100 turbofan engines give the F-15 incredible power, enough to accelerate to Mach 2.5 in a flash, enough to stand the aircraft on its tail. The F-15 is the first fighter with more engine thrust than weight. It carries a pulse Doppler radar that lets the pilot look down and shoot down. His elevated seating, surrounded by a bubble canopy, gives him 360 degrees of vision as well as the ability to look over the side and thus below his aircraft. The F-15 is not as small as some would have liked, but its size was the price of its immense power and maneuverability, the latter arising from twin rudders and large horizontal surfaces. The plane can turn on a dime and can outmaneuver any foreign fighter in the world. The horizontal tail surfaces alone are as big as the wings of a MiG-21. One very lucky pilot, involved in a midair collision that sheared off a large portion of one wing, discovered that his F-15 still had enough lift to get him home safely. Size also makes room for some formidable armament: four Sidewinder AIM-9 heat-seeking missiles, four Sparrow AIM-7 radar guided missiles, and a powerful 20mm cannon. The F-15, in conjunction with the later developed F-16, now patrols the skies over U.S. cities. As of this writing, the F-15s flown in combat by U.S. and Israeli pilots have racked up a kill ratio of 104 to zero.

THE LESSON OF THE THANH HOA BRIDGE

Once an air force has won control of the skies, it must move on to its major missions—the destruction of an enemy’s infrastructure and the support of its own troops on the ground. Neither job is easy; the Thanh Hoa bridge became a prime example. The bridge, spanning the Red River south of Hanoi, was a major logistics artery for the forces of North Vietnam, and thus a prime candidate for destruction early in the war. On April 3, 1965, forty-six F-105s attacked it, to no avail. Bombs missed or bounced off the concrete abutments, while the run-in to the target was a killing field for the North Vietnamese antiaircraft gunners. Over the next three years, 869 missions were flown against the bridge at Thanh Hoa, with no results other than the loss of eleven aircraft and their crews.

From 1968 to 1972 there was a halt to bombing in the North. During that interlude, ingenious engineers looked into the guidance of bombs and artillery shells by means of laser beams. The work paid off. On May 13, 1972, a strike force of F-4s again attacked the Thanh Hoa bridge, but this time they were better equipped. The raiders delivered two dozen laser-guided bombs in that one raid; the Thanh Hoa bridge was dropped into the river, rendered useless for the rest of the war. During the following month, laser-guided bombs dropped fourteen more bridges.

Other members of the technical community were experimenting with the use of TV cameras in the nose of air-to-surface missiles. This class of weapons was given the name Maverick; its great advantage was that the host aircraft could leave the scene after launch; no continuous illumination of the target was necessary. Later variants turned to the use of infrared images. A half-dozen versions of Maverick were developed and deployed during the 1970s, all most useful in attacking armored vehicles and heavily defended installations, since a Maverick’s shaped-charge warhead can penetrate over two feet of steel.

In the air-to-air battle, the missile improvements on our watch related to smokeless motors and all-aspect infrared trackers. In the early dogfights over Vietnam, a pilot had to get on his adversary’s tail to lock onto the heat from the target’s engine. In the mid-seventies we developed “all-aspect” trackers. They can lock on from any angle, before the “merge,” as adversaries initially approach each other head-on.

By the end of the seventies these smart, imaging, and laser-guided weapons were all part of the Air Force inventory. We were ready for the tanks and bunkers of Iraq. In 1991, 9 percent of the weapons dropped on Iraq were precision-guided munitions. By 2003 that figure had risen to over two-thirds.

THE LESSON OF LETHAL GROUND FIRE

The support of troops on the ground is even more difficult than blowing up bridges or buildings. Shooting up a tank or a truck convoy requires a low-altitude approach by an aircraft at speeds slow enough to lay down plenty of rocket or cannon fire. Imaging weapons may be too expensive for the job, and bombing does not work. An iron bomb must land within twenty-five feet of a truck to do much damage. A direct hit is required to kill a Russian tank. But the average miss distance for bombs dropped in Vietnam was 323 feet. To achieve the accuracy needed for a kill, a flying gunship is needed, but such low-and-slow aircraft are vulnerable to small arms fire, machine guns, and antiaircraft artillery.

As the war in Vietnam wore on, a succession of Air Force officials entered into joint agreements to do something to improve close air support for ground troops. The eventual solution was to start from scratch: design an aircraft that could carry tank-killing armament, withstand small arms fire, and loiter over ground targets at low speed.

In April 1970 the Air Staff approved a concept paper for the development of a prototype AX (Attack Experimental) aircraft; two years later the A-10 began full-scale development. It was unlike any other attack aircraft ever built. For redundancy, it had two engines, spaced far from each other, so an explosion in one was not likely to damage the other. They were low-thrust, high-bypass engines, not attractive to hotshot fighter pilots, but economical in the consumption of fuel, and hard for heat-seeking missiles to find. The A-10 would loiter over the battlefield for five hours at a time. Designed with very large, straight wings, the resulting airplane could operate from small airfields close to the front lines; 4,000-foot runways would do.

The unique and least visible feature of the A-10 was the protection afforded the pilot and his cockpit equipment. They sat in a titanium bathtub impervious to small arms and machine-gun fire. More than that, the bathtub could withstand direct hits from a 23mm antiaircraft gun. The pilot’s head and shoulders were protected by a bulletproof windscreen. The fuel tanks were filled with a fire-retardant foam, akin to a sponge that would accommodate the liquid but extinguish any conflagration if tracers or cannon shells hit the tanks.

Then there was the payload, the 30mm GAU-8 Gatling-gun cannon. I fired it once at a test range and have never seen or heard anything like it. A 30mm round is over one and an eighth inches in diameter, and each round is made of depleted uranium 41 and weighs three-fourths of a pound. Yet the gun can fire seventy rounds per second, each leaving the barrel at over 2,300 mph. The effect on a heavily armored tank a mile away is devastating, lethal to the occupants. The A-10 also was designed with eleven hard points under the wings and fuselage, fixtures on which to hang missiles, smart bombs, or other ordnance.

The first of these aircraft flew in February 1975. John McLucas ordered them into production on his watch, although the first squadron did not go operational until after I got there, in October 1977. The A-10s acquitted themselves well in the Persian Gulf and beyond; the real problem was to get them produced in the first place. The budgets for these unglamorous airplanes had to be shepherded and protected by the Secretaries of the Army and Air Force at every turn. All told, 713 were produced, and most experts now find them indispensable in our post–Cold War conflicts.

FLIGHT SAFETY RULES CAN BE HAZARDOUS TO A PILOT’S HEALTH

Bureaucracy can kill just as surely as bullets. The U.S. Air Force entered the war in Vietnam armed with a policy known as the Universally Assignable Pilot. The idea was that every pilot should be able to fly virtually any airplane in the Air Force inventory. The purpose of this policy was flexibility, to give the Air Force the ability to focus talent where it was most needed. The result was inexperience, disastrous during the trying moments of intense combat. When tracers are flying past, a SAM is rising, or the fire warning light goes on, there is little time for “universal” pilots to reflect on where the levers and buttons are in this particular airplane.

The other hazard to the survival of new pilots, oddly enough, was the sanctity of flight safety rules. During flight and then combat crew training, the protection of the aircraft and the safe return of the pilot became the primary criteria for judging a training unit’s performance. This meant that realistic combat maneuvers, dogfights lacking only live ammunition, with gut-wrenching dives to the nap of the earth, were out of the question. The result of this risk-averse approach was some lethal on-the-job training for new fighter pilots once they got to Vietnam. The statistics were interesting: a pilot’s first ten missions were his most dangerous; after that there were few losses.

Major Moody Suter was only one of many fighter pilots who noticed these facts of life in Vietnam, but he was the most persistent in doing something about them. He and his comrades badgered their superiors into doing a better job of simulating adversaries during combat training. In the early days of Vietnam, flights of F-4s would mix it up with each other in the skies over their own bases, but F-4s flown by Americans do not resemble MiG-21s flown by Russians, Chinese, or Vietnamese. The MiG-21 is significantly smaller, harder to see, and much more maneuverable than the F-4. The MiGs’ tactics also were much different from our own.

In the fall of 1972 the young American pilots talked the Air Force into creating the 64th Fighter Weapons Squadron, an “Aggressor Squadron” equipped with T-38s, then F-5Es. These small, supersonic aircraft were flown by instructors who had studied MiG tactics. They flew against green F-4 pilots. The results were impressive but incomplete. A similar approach to air-to-air combat training, known as Top Gun, was initiated by the U.S. Navy in 1969.

In the spring of 1975, with the war in Vietnam over, Major Suter took his statistics and ideas to the Air Staff, to Secretary McLucas, and to General Bob Dixon, commander of the Tactical Air Command. Suter had flown 232 missions in Vietnam, so he knew what he was talking about, and he convinced Dixon. The product was Red Flag, a plan for new pilots to log their first ten combat missions in a fully realistic but hopefully nonlethal training environment. The exercises would be expensive, involving the full panoply of tankers, electronic countermeasures, aggressor squadrons, integrated missile and antiaircraft systems, as well as instrumentation to keep track of hits and thus bring home the evidence. These dangerous lessons had to be learned and committed to memory. There could be aerial collisions; distracted pilots might fly their aircraft into the ground. Accident rates were bound to go up, but the increased life expectancy in battle would be worth it.

The Red Flag range was built at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada, and the first exercise was conducted in November 1975. Thirty-seven aircraft were involved, along with a ground environment heavy with Soviet and Chinese equipment. These exercises continued during McLucas’s and my tenures. We lost twenty-four aircraft to midair collisions and ground impact over the first four years of Red Flag. During the first year alone, the all–Air Force accident rate was 2.8 crashes per 100,000 hours of flying time. At Red Flag it was eleven times that, at thirty-two accidents per 100,000 hours. The largest single problem was collision with the ground as trainees tried to fly under radar coverage or got too low when delivering weapons.

Congress was horrified, but we pressed on. The results showed in the wars that followed. Pilots returning unscathed from early missions over Iraq in 1991 agreed that the combat there was a picnic compared to the rigors of Red Flag. In time, the Iraqi Air Force fled to the dubious safety of Iran rather than continue to face the USAF. A decade later, the Iraqi Air Force was nowhere to be seen.

THE PROBLEM OF COST—THE NEED FOR NUMBERS

As the USAF began to rebuild its aircraft inventory, the matter of economics crept in. Big two-engine planes are expensive to buy, although they may be cheaper in the long run because the two engines provide more reliability, a better chance of getting home after a flameout. They have more power and thus can achieve higher speeds, and they can carry more avionics, such as the radar that allows pilots to dominate the skies. But those advantages carry a price tag, and the lessons learned in other wars made it clear that high attrition rates must be expected in future air battles. Numbers count.

In 1972, McLucas initiated the development of competing single-engine prototype lightweight fighters. After a flyoff in 1975, McLucas announced that the General Dynamics F-16 was the winner, based on its agility, acceleration, range, fuel efficiency, and lower cost. In June 1975, four of our NATO allies followed suit. The F-16 was to be produced as a NATO aircraft, with components manufactured in Norway, Denmark, and Belgium, with some assembly to be accomplished in the Netherlands. Major production would take place at the General Dynamics plant in Fort Worth, Texas. The negotiations to make all this happen were intricate, but they succeeded, thanks to the guiding genius of Air Force Assistant Secretary Frank Shrontz.

When the first F-16 squadron became operational, in October 1980, its capabilities became obvious. It carries no long range radar, but once in a dogfight, it’s unbeatable. It has also evolved into an effective carrier of smart munitions. The United States has produced 2,200 of these aircraft so far. They are a favorite of our allies and other export customers.

THE HIDDEN COSTS OF VIETNAM

Vietnam was not just a war, it was a crusade to defend those who chose freedom from the Viet Cong terrorists. But it incurred a terrible cost. Some of those costs were tangible and obvious, but others were not. Domestic needs went unmet, the dangers of inflation were ignored, and the strategic forces of the United States fell into disrepair. By 1970 the Soviet Union had achieved parity with the U.S. in many measures of strategic nuclear firepower. If those trends continued unchecked, the Soviets could achieve the power to blackmail, to operate below the nuclear threshold, with a free hand.

This disintegration started in 1961, a year of major and serious confrontation between the U.S. and USSR, when every crisis, from Vienna to Berlin to surprise nuclear tests, should have sounded the alarm. The Cuban missile crisis of 1962 made matters worse, yet that was the year when the last B-52s and B-58s were delivered to the Air Force, the proposed B-70 bomber was cancelled, and Skybolt development ended. The latter was a joint U.S.-UK effort to produce an air-launched attack missile that would extend the life of the bomber fleet. Its unilateral cancellation infuriated the Brits.

As Vietnam began to devour more of the defense budget, ICBM modernization slowed and the construction of new silos stopped. In the 1970s the new Nixon administration tried to stem the tide of Soviet advances with ABM and SALT treaties, but once those agreements were in hand, the Soviets unleashed a new series of missile tests that made clear their goal of ascension to a position of strategic nuclear superiority. It was this landscape of emerging Soviet SS-18 rockets, an aging U.S. bomber fleet, and a Brezhnev Doctrine seeking global hegemony, that cried out for attention as the war in Vietnam wound down.

The cures to the Air Force’s strategic weapons problems were varied, but they began to receive my attention in 1976. The remaining B-52 fleet was to be refurbished with new wing structures, improved engines, and modern avionics. Cruise missiles were developed to allow those bombers to operate in a stand-off mode, then to challenge the entire Soviet defense system with ground-based models. A new long range bomber, the B-1, was put into production, with a radar cross section only 1 percent of the B-52’s. The Commander-in-Chief of SAC was delighted to discover, in 1976, that U.S. radars could not find or track the experimental B-1 he was flying in a bombing competition. But that was only the tip of the iceberg. It turns out that stealth, the greatest challenge ever posed to the air defense systems of the Soviet Union and its client states, was conceived within the Soviet Union itself.

In 1966, Pyotr Ufimtsev, the chief scientist at the Moscow Institute of Radio Engineering, wrote a paper entitled, “Method of Edge Waves in the Physical Theory of Diffraction.” In this arcane and virtually unintelligible paper, Ufimtsev applied Maxwell’s equations to the reflection of electromagnetic radiation—that is, radar—from various two-dimensional geometries. Senior Soviet designers were uninterested in his work, but in 1975, upon the translation of this paper into English, an astute scientist at Lockheed’s Skunk Works sat up and took notice. It became clear to Denys Overholser that Ufimtsev had shown the way to calculate, rather than just model, the radar cross section of any object. Furthermore, these calculational tools could then be used to design the specific contours of an aircraft so as to render it virtually invisible to radar of any kind.

Testing of the radar returns from competitive stealth models started in 1975; development of a stealthy aircraft started on my watch, in 1976. Bill Perry, the succeeding Director of Defense Research and Engineering, pushed the program hard. A prototype aircraft first flew on December 1, 1977, and the first production of the F-117A flew on June 18, 1981. It was deployed as a secret “silver bullet” in three squadrons, none visible until needed on the opening night of Desert Storm.

Pyotr Ufimtsev came to lecture at UCLA once the Cold War was over. Until his arrival in the United States, he was unaware of his contribution to the American stealth program, but he was not surprised. Not only were his Russian peers disinterested in his work, they did not have the computational power to utilize his gift. It took a Cray I to design the F-117L, a Cray II to move up to the rounded contours of the B-2.

In the field of ballistic missiles, we set about doubling the effectiveness of the existing Minuteman III, with improved warhead yields and guidance upgrades. Then we pursued the full-scale development of an MX missile that was to replace the 1960s’ weapons with a system that would redress the Soviet’s advances. To command and control these new assets, the civilian leadership of the 1970s supported Air Force visionaries trying to move into space. The Global Positioning System was a prime addition to the reconnaissance assets described in the previous chapter. The development and purchase of AWACS 42 aircraft brought tremendous new capabilities to the tactical arena.

By the end of the 1970s most of these fixes had taken hold. Only the B-1 production authorization, initiated in December 1976, was cancelled, by President Carter. It was restarted by President Reagan in 1981, but the off-and-on-again costs more than doubled the aircraft’s unit price. This ballooning cost for no net gain might be the most important fiscal lesson to emerge from the Vietnam era: the constant restudy of decisions already made, the regular recasting of ongoing programs, is terribly wasteful and produces little in the way of useful results.

THE TYRANNY OF LEAD TIMES

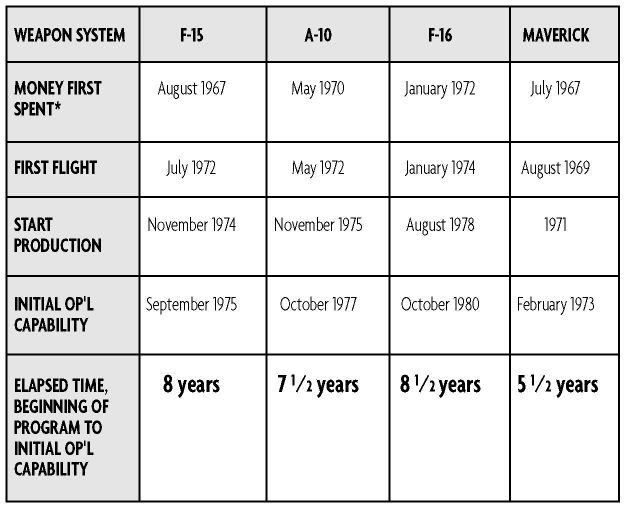

The technocrats who managed the recovery at home during those post-Vietnam years did not have an easy time. The Watergate Congress, elected in 1974, was intent on disassembling American military power, and they nearly succeeded. That would have been a disaster of unimagined proportions, because one aspect of the paradox of Vietnam is the tyranny of lead times. Consider the timeliness of the weapons systems described in the preceding pages:

* The date when the bureaucracy started to spend serious money, not just talk. In the case of the three aircraft programs it refers to the first funded requests for proposals from industry, once the Air Force had thought through what it wanted. In the case of Maverick it refers to the CSAF’s Paveway decision, a roadmap for smart munitions.

It took about eight years from the time the Air Force decided to invest resources in a major project until that aircraft’s first squadron was operational. Add another year or two to get a major deployed force, and the lesson becomes clear: No President or administration can deal itself a stronger hand. Every President is dependent on the technology and production inserted into the pipeline by his predecessor(s). A disruption of this recovery by the 1974-78 Congresses would have precluded the Reagan buildup in the 1980s and could have stalled the Cold War victory that followed.

PEOPLE

More than anything else, Vietnam changed the people of America. It changed their attitudes, their support for the armed services, and the outlook of those who made a career of the military. In the aftermath of Vietnam, the draft ended. The services had to rely on volunteers, kids who wanted to be in the military. It was not an easy transition for the Army. The Air Force had more to offer in terms of training applicable to future careers, but even so, we had to recruit.

The good news is that the post-Vietnam generation did step forward, and for the first time in history they were joined by large numbers of women. The military academies opened their doors to women, a complicated but eventually rewarding transition. The arrival of female cadets represented a great infusion of new blood into the officer corps. It has worked out well; only a few arguments remain about the role of women in combat. The daughter of a recently retired USAF chief of staff flies refueling tankers every day. The current chief has three daughters in Air Force blue.

The advent of smart munitions required the retention of smart enlisted troops to care for those weapons. Attention to the careers of the senior enlisted men and women, care for their families, became a top priority as the Air Force recovered from Vietnam. At the top of the pyramid lay the future of the Air Force itself. When the war in Vietnam started, Curtis LeMay was the chief of staff. The leadership of the Air Force was dominated by the SAC/nuclear weapons/bomber pilot culture. The fighter pilots, airlift people, logisticians, scientists, and engineers all were relegated to second-class status.

The Constitution and the law are quite clear. The selection and assignment of general officers is key to the civilian control of the military, but that control has often been abandoned to the senior officers of the uniformed services and neglected by the civilians charged with looking out for the national interest. In the mid-seventies, Deputy Secretary of Defense Bill Clements and the service secretaries decided to reassert control of this system. I wanted to see R&D program managers, information systems people, and fighter pilots promoted to the rank of general, as well as bomber men and women. It was not an easy time, but when the board cycles were over, I think the Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel and I had become close friends. The fortunes of those who had been learning the lessons of Vietnam began to ascend. Among the first to understand the paradox of Vietnam—that we all must die a bit before we grow again—were the men who had flown there.

Those unfortunate enough to have spent reflective time in Hoa Lo prison came home to address the political issues. Many ran for, and some won and served with distinction in, the United States House and Senate. Their contribution was to make sure the United States never again entered wars gradually, with unclear aims and unfocused operations.

The men who stayed alive and kept flying brought home more specific visions. They brought their experience to the Air Staff and the secretariat, to see to it that the intellectual and financial firepower of those institutions were brought to bear on the building of a whole new Air Force. To these veterans of the skies over Vietnam, “recovery” was not just a matter of restoring the status quo. It was not simply an effort to recover the honor of a badly mauled Air Force, for that Air Force had already acquitted itself with honor far above and beyond the call of duty. These pilots were determined that their service become a preeminent global power, able to control the skies and, if necessary, destroy the nervous system and muscle of any power endangering the American people. They were determined that their comrades on the ground never again suffer wars of attrition, that they never again endure the horrors of Ia Drang and Khe San. They saw to it that their successors would be able to deliver a withering and accurate fire from the sky, the likes of which had never been seen before, while limiting the collateral damage to innocent civilians.

They succeeded in reshaping the U.S. Air Force, perhaps beyond their wildest dreams. In 2003 one air raid destroyed five hundred armored vehicles and artillery pieces in an elite Republican Guard division. Only infantry with small arms were left to fend for themselves. A surviving POW described the attack: “When the bombs hit the tanks, we ran for our cars. When we turned on the ignition, the bombs hit the cars. It was terrible.”

While the new U.S. Air Force cannot win wars all by itself, it now can see to it that most American soldiers, sailors, and airmen come home safely. Iraq and Afghanistan have replaced Vietnam in the American lexicon of warfare.

Exhibit A is Joe Ralston, mentioned earlier as the pilot passing over the MiG-21s at Phuc Yen. He went on to fly more than 150 missions over Vietnam. He made it home alive, although many of his fellow F-105 pilots did not: 334 of those aircraft were lost to enemy fire. Upon his return, Ralston brought his experience to bear at the headquarters of the Tactical Air Command. By 1976 he was serving on the Air Staff, helping to define the new U.S. Air Force. Ralston went on to help with the development of stealth technology, then to assume command of tactical air forces on alert around the globe. At the culmination of his Air Force career, Joe Ralston became the four-star general serving as the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe (SACEUR).

I have no doubt that if the U.S. President and Congress decided that some European dictator or ideology threatened the safety and security of the American people, General Ralston would not let the air forces that threatened us taxi around their runways unmolested. Nor would he allow the ground troops under his protection to suffer needless deaths. He would oversee the destruction of our enemies, those who would harm our families and destroy our institutions, with a fire from the sky unimaginable when he was a young lieutenant. With Joe Ralston as SACEUR, with F-15s and F-16s patrolling the skies over Washington in the aftermath of 9/11, and given the performance of the USAF in the skies over Iraq, I think the recovery from Vietnam has turned out pretty well.