CHAPTER 14

Inefficiency Kills—Empires as Well as People

NATIONS DO NOT RISE TO EMINENCE nor do they come to power simply because their chariots (or their airplanes) are bigger, faster, and more numerous than anybody else’s. Nations prevail on the world stage because they enjoy a broad spectrum of power.

President Eisenhower believed the U.S. could prevail in the Cold War not by force of arms but by the strength of its economy. To that end, he demanded good intelligence. Then, based on that intelligence, he invested a modest share of his nation’s wealth in the maintenance of its security while our citizens built a prosperous, strong, and just society. Eisenhower did not try to flood the world with armaments or American troops. He entrusted the nation’s security to thermonuclear technology. He worked to be sure those weapons never would be used, then turned his attention to our economic health and infrastructure. When he left office, he had set the ground rules for the decades to follow: nuclear deterrence, containment of communism abroad, and economic growth at home. He warned of what might happen if those forces got out of balance. In his often quoted farewell, he referred to the dangers of a military-industrial complex. In so doing, I believe he was urging a continued reliance on a small, focused, and well-controlled thermonuclear deterrent.

Ronald Reagan understood the need for that balance, but he also understood that the free and growing economy bequeathed to him by Eisenhower and his successors was now his ace in the hole. By playing that card against the empty Soviet hand, Reagan could end and win the Cold War. The Soviet gerentocracy tried to cling to power amidst a sea of change, but younger minds in that government decided to deal with reality. The facts they had to face were not about fallen castles or lost ships. They were the economic facts of life.

THE VIEW FROM THE WHITE HOUSE, 1982

In the 1960s, I took an interest in politics. Like many of my generation, I felt that the Johnson-McNamara approach to Vietnam was couched in naiveté and deception, leading to disaster. To me, Ronald Reagan seemed the right person to restore integrity and common sense to the nation’s leadership. As a result, in 1965, I enlisted in Reagan’s campaign for the governorship of California. Afterward, I worked briefly in Sacramento, then turned my attention to his 1968 on-again, off-again initial run at the presidency. I helped Reagan gain and keep control of his state legislature, in the process dethroning his likely challenger to reelection. In 1970, I assumed full responsibility for the direction and management of Reagan’s gubernatorial reelection campaign.

During those years, we talked, and I listened, endlessly. I prepared some speeches, hired the key staff, and tried to measure the public’s reaction to his policies and campaigns. We traveled and often lived together. In the process I came to know Ronald Reagan as well as any of my contemporary peers, and in that same process, he came to entrust me with much of his political fortune.

As the 1970s unfolded, my career turned in other directions. I went to work in Nixon’s Pentagon, and then, in the aftermath of Watergate, became Gerald Ford’s Secretary of the Air Force. Throughout those years, Reagan and I stayed in touch. We talked about Brezhnev’s arms buildup, about President Carter’s proposed SALT treaty, and about the politics of Texas.

I was not involved in either of Reagan’s 1976 or 1980 presidential campaigns, and once he won the White House, his first priority was the economy, so there was little reason for us to talk. My first communication with him was in October 1981, as he turned his attention to national security affairs. At the end of that year, he restructured his National Security Council (NSC) staff along lines that perhaps only coincidentally matched my October advice. On January 21, 1982, I was drawn back into the Reagan orbit, reporting to work on the staff of Judge William Clark, Reagan’s new National Security Adviser. As I began to pore over the National Intelligence Estimates, one fact jumped out at me: the Soviets were going broke.

That was not the conventional wisdom of the inbred academic-intelligence community that studied the Soviet economy for years. They were impressed by the post–World War II industrial recovery of the Soviet Union, but they could not or would not recognize the onset of diminishing returns in such a top-down system. The academics had gotten into the bad habit of accepting and using official economic data published by the Soviet government. In the early 1970s their conventional wisdom was that the Soviets were spending only 5 percent of their GDP on defense. By 1980 the consensus of the intelligence graybeards had shifted only slightly, estimating a 2 to 3 percent annual growth rate, with 15 percent of the GDP devoted to defense.

There were dissenting voices, however. Andy Marshall, the longtime Director of Net Assessment at the Pentagon and an ally of onetime economist James Schlesinger, thought differently. So did Bill Lee at the Defense Intelligence Agency. They felt there was no real growth in the Soviet system, that the academic estimates of Soviet defense spending were low by a factor of three or four, and that the denominator of this indicator, the real size of Soviet GDP, was badly overstated. By the beginning of the Reagan years, Marshall and his allies felt that “defense” was eating up 35 to 50 percent of the Soviet GDP.

These dissenters pointed to the size of the Soviet naval support fleet: ferries in the Baltic overdesigned to transport armored divisions; doubly redundant tankers, nominally benefiting the Soviet fishing fleet, but actually there to extend the reach of the burgeoning Soviet Navy. They pointed to the massively reinforced concrete highways between Soviet and East European villages, built to accommodate the rapid movement of tanks. They noted the huge buildup of war reserve stocks of everything from ammunition to fuel to blankets, totally unnecessary for any rationally functioning economy. 43 They called attention to the cost of supporting client states, like Cuba and Somalia. Where once these distant lands had been the source of plunder, in time they had become expensive socialist showcases and overstaffed intelligence-gathering stations. Marshall derided the then-current CIA “fact book,” a tome that estimated the East German per capita income to be on a par with the West. In reality, the East lagged by a factor of two. These views were corroborated by Western businessmen trying to deal with the Soviets. Those travelers brought home tales of incredible inefficiency, factories still locked into pre-World War II ways of doing things.

In 1981 economist Norman Bailey joined the NSC staff. He began to collect evidence of Soviet hard currency shortages and economic failures. At the same time, Stanford’s Henry Rowen accepted the chairmanship of the National Intelligence Council. That body, the meeting place for officers from the entire intelligence community, undertook a more rigorous analysis. When they were done, these men and women converged on a view of the Soviet Union very different from that espoused by the establishment for years. Their conclusion: the economic system of the USSR was broken and on the verge of collapse.

Bailey’s evidence and Rowen’s arguments all made sense to me. The Soviet Union was not the sort of customer to whom I would extend credit. Solid indications came from reports of Soviet asset sales. They were dumping gold into a declining market. They were taking short-cuts in their production of crude oil, ignoring the long term for the sake of immediate cash. They were penetrating and attempting to manipulate the wheat exchange and the currency markets. The evidence was fragmentary and anecdotal, but there was enough to suggest that the Soviet economic chickens were headed home to roost.

Only in the decades to come would we learn the facts. Once the CPSU lost control of the archives, once Western engineers and businessmen were free to meet with their Russian peers, only then did a true picture of the Soviet economic carnage emerge. A few snapshots of what we now know follow.

OIL

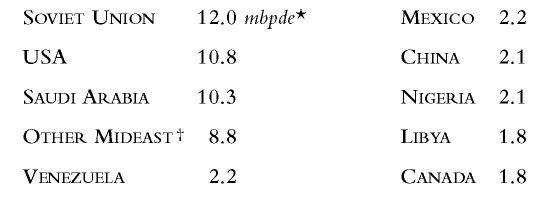

It is not widely understood that the Soviet Union was once the world’s leading producer of oil and gas. The big ten producers in 1980 were as follows:

* Millions of barrels per day equivalent. At $27/bbl, one mbpde becomes $10 billion of annual revenue.

†Iraq (2.5), Kuwait (1.8), UAE (1.7), Iran (1.7), others (1.1).

In addition, the enormous mineral wealth of the Soviet Union kept that strange economic experiment going for much of the twentieth century. The USSR was rich in gold and diamonds, in bauxite and timber. But it was black gold that paid the rent. The oil shocks of 1973-74, when the world price tripled, and then 1979-80, when it tripled again, kept breathing life back into the dying Soviet economy. The Reagan administration’s interest in pushing down the world price of crude oil and in blocking the sale of natural gas to Western Europe was not simply a reflection of the need to stem inflation in the U.S. It was a conscious effort to suffocate the Soviet economy.

After those price run-ups in the seventies, the world price of crude oil dropped steadily in the eighties, falling by a factor of three, in real dollar terms, during the first half of that decade. Every one dollar drop in the world price of oil cost the Soviet Union perhaps a billion dollars in annual hard currency earnings. The creaky Politburo of Leonid Brezhnev began to panic. It demanded the immediate production of oil regardless of the long-term cost. It was this full-throttle, devil-take-the-hindmost approach to oil production that was a key indicator to us at the White House.

In 1991, when the Soviet empire died and the autopsies began, Western oil executives and engineers began their travels to the former Soviet Union. From the frozen wastes of Siberia to the desert steppes of Kazakhstan, they brought home tales worthy of a Harrison Ford movie. They found real oil country: well-defined geologic structures and immense petroleum reserves. Some oil-bearing formations were thousands of feet thick. They found well-trained, top-flight mechanical, chemical, and petroleum engineers, as well as middle managers who were affable and open, eager to share their knowledge of Soviet geology. Unfortunately, they also found reluctant bureaucrats, a rigid approach to oilfield development, and little understanding of reservoir engineering.

After World War II, Stalin had seen to it that the Soviet Union did a good job of mapping its raw materials. The geophysical work was good too, although the technology lagged behind the U.S. by about ten years. There was no computer-generated 3-D mapping of underground structures, only 2-D slices along a survey line, with the results used to plot underground contour maps.

The serious problems began to show up when the Soviets moved from exploration to drilling.

By 1990 they had exploited the more obvious, shallow oilfields. They needed outside help for the deeper structures. Specifically, they needed technology, management, and money. Drilling to depths of over 10,000 feet into hot, high-pressure formations strained their capabilities. The frequent presence of corrosive and poisonous hydrogen sulfide gas made matters worse.

Soviet problems started with the drilling tool itself. The technology of making a hard rock drill bit that would stand up to the hot, high pressure and corrosive environment below 10,000 feet was difficult for them. Soviet tools could drill for only a hundred feet or so before wearing out, less than 10 percent of Western practice. When one must pull two miles of drill stem to replace a tool after drilling only a hundred feet of hole, the economics of the business go negative: it costs more to drill the hole than the recovered oil is worth. Even so, to the Soviets that was the good news. The bad news was that sometimes the drilling simply had to stop. Downhole conditions got to be impossible. In one field alone, the visiting Western engineers found dozens of wells drilled, with virtually none completed to the point of production.

For lack of spare parts and maintenance, there were more rigs idle than running. Those running, seldom, if ever, had working gauges. The observed fire protection system was a bucket of sand and a shovel. Then there were the environmental and safety problems. A Soviet tractor inadvertently plowed up a major pipeline. Oil poured out, covering hundreds of acres. There was no rush to shut off the flow, although berms were erected around the spill to contain it. When asked about vacuum pumps to suck up the spill, the Soviet engineer involved looked bewildered. He had never heard of such things. Once the flow was stopped and the berms were in place, the spilled oil was set on fire to make it go away.

Other Western oil experts, visiting the oilfields in remote Siberia, found cities built in the middle of nowhere. There were fountains and parks, usable only in the few short summer months, boulevards and paved roads, huge Stalinesque apartment buildings and hydroponic farms. The designs were grandiose, but the execution was ghastly, with utilities added as an afterthought to the outside of buildings, fully exposed to the harsh winter weather. These buildings were sized to accommodate not only the drilling crews, their families, and the support staffs, but the huge political overhead involved in any Soviet effort. No Western oilfield could have supported such monstrosities.

The drilling procedures were equally bizarre. A visiting Canadian geophysicist told of the Soviets drilling through hundreds of feet of permafrost to find oil and gas. When completing those wells, they did not bother to insulate the well casings. As a result, when the hot gases began to flow up from the reservoir, they melted the permafrost, creating an annular leak around the pipe. A trillion cubic feet of gas escaped.

But the heart of the Soviet oil problem was neither technology nor the inefficiency of their drilling teams. It was reservoir engineering: drilling the right number of wells in the right places, then adjusting the production from each well to optimize the present day value of the resulting production. There was no place in communist doctrine for the “time value of money.” Thus the Soviets had no idea how to calculate discounted cash flows. They had no conceptual tools with which to optimize their production plans.

Oil is found in geologic traps. Being lighter than water, oil migrates upslope to the top of its structure, be that a fault or a dome. The purpose of geophysical surveys is to find those structures. An exploratory well confirms the location of that structure, sees if it contains any oil, determines the nature of the oil-bearing formation (porosity, permeability, etc.) and then locates the oil-water interface. After each such experiment—that is, each well—one compares the well logs with the geophysical model, revises the model, and drills again. With this data, one then plans the extraction of oil so as not to leave behind pools of oil, surrounded by water, that can never be recovered. Producing an oil well wide open, early on, can leave behind many such unrecoverable pools of oil. Choking well production down will result in more oil being produced over the long term, but will slow production to an economically unacceptable rate. In the West, the balancing of these competing considerations is the essence of good reservoir engineering.

Not so in the Soviet Union. During the days of Soviet management, a potential oilfield was outlined by geology and geophysics. Then a standard template was applied and the wells were drilled with Stakhanovite zeal, each independent of the others. The goal, the basis of each manager’s perks and bonuses, was the number of wells drilled. It was not wells completed, oil produced, or budget compliance. No Soviet engineer was ever able to tell my friends what it cost to drill a well; any American oilman knows those costs to three significant figures. If a Soviet well was completed and connected to a pipeline, it was run wide open, with no choke. The damage to the reservoirs was irreparable.

And then there was the problem of turning the oil produced into money. The transmission facilities, used to get product from wellhead to market, leaked badly. When delivered to Soviet cities, the product entered the price-free Soviet system; no meters and no costs were attached to the profligate use of energy, because it was “free.” Oil and gas belonged to “the people.” Even when delivered to ports for export, the state had problems in getting paid. In part that was because some of the recipients were deadbeat socialist client states. In other cases, the oil was shipped by hard-to-follow trucks for the personal benefit of the oil barons. Only a small amount of the Soviet Union’s oil and gas production actually made it to the ports at Rotterdam and the factories of West Germany, and thus into the world’s hard-currency markets. History might have turned out differently if the management skills and petroleum engineering of the Arabian-American Oil Company had been matched to the technical competence and dedication of the Russian oilmen, but that was not to be.

THE SOVIET DEFENSE BUDGET

In the Soviet sunset years, Boris Altshuler, son of an eminent nuclear weapons physicist, began researching the cost of the mad Soviet military scramble. He now talks about hundreds of Chernobyls; rivers and lakes full of plutonium, acid, and reactor wastes; explosions at chemical warfare plants. But his most compelling numbers are economic: the data on how various nations spent their national income during the Cold War.

“National income” is a UN term that approximates Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Altshuler first published his conclusions in 1971 and has been updating them ever since. He concluded that military spending in the Soviet Union in 1969 was 41 to 51 percent of national income, not including military construction. Expenditures for the latter were deeply buried in the capital investment part of the state budget. Folding reasonable estimates for those in, Altschuler now concludes that total defense expenditures in the Soviet Union were about 50 percent of national income in 1969, rising to 73 percent in 1989. His conclusion matches a statement by former Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze to the effect that the defense budget ate up as much as 50 percent of the Soviet Union’s gross national product annually. At the end, Gorbachev admitted: “The Politburo had no idea of the real role of the VPK [the military-industrial complex] in the state budget.”

Altshuler’s estimates of national income devoted to defense seem reasonable because, using consistent criteria and methodology, his estimate of U.S. defense expenditures in the 1960s was 11 percent of national income. The official U.S. number for 1966 was 9 percent of GDP. That was during the war in Vietnam, and even that level of expenditure led to the guns-and-butter inflation of the seventies. Today the United States spends about 3 percent of its GDP on defense. Israel, a small state in mortal peril, spent about 25 percent of its GDP on defense during the 1970s. It could only afford to do so because of its U.S. subsidy. During World War II the United States spent 40 percent of its GDP on defense. We could not have done so much longer. The Politburo’s misallocation of half its wealth to defense, decade after decade, rising to three-quarters by the end, was a death sentence for its empire.

COSTS

Not only did the Soviets overallocate their resources to “defense,” it mismanaged those expenditures on a scale that boggles the mind. Soon after the USSR ceased to exist, various freelance organizations made their way into the scattered fragments of that country, trying to help. I was called in by the International Executive Service Corps (IESC), a nonprofit foundation started in 1964 to help agrarian economies, mainly in South America, benefit from the experience of retired U.S. executives.

When the Berlin wall came crashing down, the IESC expanded its services into the former Soviet Union. A former college friend of mine, mindful of my Livermore and high-tech business experience, called on me to go to Kharkov, an industrial city on the eastern end of then newly independent Ukraine. I was to help commercialize a once-mighty Soviet technical institute.

Ukraine is a lovely country, the pre–World War I breadbasket of Europe. Then Stalin deported the successful independent farmers, known as kulaks, starved out the peasants, and stumbled into war. I have never seen such incredible black earth as in Ukraine. But the glory days of Ukrainian agriculture are gone.

During my visits there in the 1990s I never saw an operating tractor, only elderly peasants swinging scythes. Today, Ukraine is energy-starved, still communist, and a net importer of food. Ukraine is a very diverse country. The eastern side, where Kharkov is located, is a part of Russia’s “near abroad,” where the people speak Russian and worship in Russian Orthodox cathedrals. When Lenin’s revolution was spreading communism across the Eurasian continent, Kharkov was the temporary, communist-dominated, capital of Ukraine. In the center of the country lies the old and magnificent capital city of Kiev, always struggling to balance East against West. In the West lies true Ukraine. Once part of Poland, the people there speak Ukrainian. They are Roman Catholics and hate the Russians with a passion. Many joined General Vlasov’s Russian Liberation Movement during World War II, in alliance with the Nazis, to fight against Stalin.

I was dropped into that stew in an attempt to help the Verkin Institute of Low Temperature Physics find new work. Kharkov was once a center of technical excellence, but Russian distrust and the smothering communist state reduced the place to poverty. The Verkin Institute was home to theoretical physicists, experimenters, and mathematicians who did world-class work. My two-week job was to help them reconfigure to attract Western investment, or at least Western contract research work. The sales pitch to the West would be: “You can rent the entire Verkin Institute for the cost of four engineers in Palo Alto.”

After a few days of orientation, talking shop and drinking vodka with some of the nicest and most hospitable men and women in the world, I asked to visit their accounting department. I wanted to know the cost of their products and services so I could advise them on a marketing strategy. I got a blank stare. “Bookkeeping? Money?” I repeated through the interpreter. Ah yes, the place where the money was handled. The management took me to a room where elderly ladies were stuffing small stacks of rapidly inflating Ukrainian currency into dirty envelopes. These were the petty cash allocations for a few key people. And that was it. There were no accounting machines, not even clerks in green eyeshades bent over dusty ledgers. There were no stacks of papers with columns of numbers. There was nothing. So I came to understand.

Raw materials were furnished to the institute according to the plan, once promulgated by GOSPLAN (the state central planning agency) in Moscow, but now set by no one. There was no purchasing department, no flexibility, no inventory records, no accounts payable, no creditors. Thus, my question about materials costs made no sense to my hosts. Workers were “paid” directly by the state. Their housing—in minuscule, walk-up apartments—was furnished by the state. Their (virtually nonexistent) food supplies were subsidized by the state. Their health care, such as it was, came from the state. And the concept of “labor cost” was incomprehensible as well. None of those people costs were attributed to Verkin’s products. At the end of the pipeline the institute furnished goods or services to other institutes, factories, or stores, again according to the plan. Verkin was not paid for anything. There were no accounts receivable, no checking accounts, no cash flow statements. Those words had no meaning. Verkin’s bottom line simply was the planners’ approval if Verkin met its quotas.

In the West we cannot comprehend the consequences of such a system. Since the word “cost” had no meaning other than as a synonym for “price”—as in, “What is the cost/price of that loaf of bread?”— there could be no accountability, no decision criteria. Without the discipline of cost accounting, with management decisions based solely on social theory, the Soviet economic distortions grew to monstrous size.

TITANIUM

As a modest example of what happens when there is no cost accounting, consider the legendary matter of the titanium shovels. When the Soviet empire collapsed, “defense conversion” became the watchwords. In 1991–92 several defense plants in the Urals hit upon the idea of making garden spades and work shovels as alternative products. The same presses that had been making armor plate and other weapons could stamp out the metal spades. The attachment of wooden handles would keep a lot of people busy. There would be no moving parts, so there would be no need for customer support. Shovels would be an ideal export product.

There was just one problem. The principal feedstock on hand at these arms plants was titanium, a very light metal that retains great strength at very high temperatures. Titanium is most often used for aircraft parts and turbine blades. In the free market economy it is a very expensive material, carefully conserved for only the most demanding uses, but in the Soviet system it was “free.” Those arms plants in the Urals started cranking out titanium shovels at a great rate, and they were a big hit, as long as the titanium lasted. In the domestic market, the peasants welcomed the new lightweight shovel, but the principal demand came from importers in the West. They melted down all the shovels they could get in order to resell the titanium at a significant markup on the open market.

PLUTONIUM

On a grand scale, a comparison of the U.S. and Soviet systems for producing plutonium provides a different kind of example. Plutonium is the touchstone of modern power politics. Its possession is the orb and scepter that separates the nuclear haves from the second and third world have-nots. Its mere presence within the borders of a sovereign state earns respect and deters the adventurism of others.

The production of plutonium is complex, dangerous, and expensive. For those reasons, not many nations have a supply. As an element, plutonium is unstable. Its most common isotopes have half-lives of 24,000 years, quite long on the human scale but short enough in the cosmic scheme of things to assure that none of it can be found in nature. It is the most popular raw material for A-bombs because only a few pounds will go critical, producing more neutrons than consumed in the chain reaction. If the geometry, timing, and speed of assembly is right, a major explosion will result.

Plutonium is manufactured in uranium piles, known as “production reactors.” A large pile of natural uranium can be made to go critical, although at worst it will melt down, not explode. In production reactors, which use slightly enriched uranium, the spare neutrons are captured by U-238 to make Pu-239. One must not leave those fuel rods in the reactor too long, however, for in time Pu-239 will capture another neutron to make Pu-240, a material that is worse than useless in A-bombs. Irradiated fuel rods are removed from the production reactor, dissolved in acid, and the plutonium is then separated out from this slurry by chemical means. The residue is highly toxic. Plutonium itself is deadly if its powders are inhaled.

In the U.S., plutonium was produced at Hanford, Washington, until the late 1980s. Even with the reasonable care and respect for human life that characterized the U.S. program, cleanup at Hanford will cost billions of dollars and will take decades. The Soviet program was not hindered by such safety constraints. The first plutonium-producing reactor was built at Mayak, near Yekaterinburg, at the close of World War II. Chemical effluent was simply thrown into Lake Kurchai. To this day children who go near that waterway soon come down with leukemia.

The problem facing the collapsed Soviet empire is that no one can or will turn off these plutonium-producing reactors. The reason is that the two reactors at Tomsk and the third at Krasnoyarsk produce not only plutonium, but heat—the only source of heat and electricity for those cities. Shut them down and those communities will freeze in the dark. As a result, the Russian Federation still runs those reactors, cranking out unneeded plutonium at the rate of one and a half tons per year.

In the mid 1990s the U.S. government initiated a series of programs to help the former Soviet Union stand down its nuclear weapons complex. There were programs to find work for the nuclear scientists and engineers (so they would not migrate to Baghdad or Tehran), to secure the nuclear weapons and materials storage sites (to preclude theft and resale to terrorists), and to close down those production facilities that seemed to be running mindlessly, tended only by the sorcerer’s apprentices. It took years for my associates at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory to gain the confidence of their Russian peers, but by the end of the decade a few of my colleagues had broken through. It was a joint endeavor. Both sides wanted to secure this part of the Russian nuclear genie, and both sides wanted the Russian economy to stop being wasteful. What these American and Russian scientists told each other provides an interesting case study of what happens when one ignores costs.

In the U.S. the production of plutonium is a sort of mining process. Fuel rods are removed from reactors. Elsewhere the by-products of parts fabrication are separated from other scrap. The resulting materials are collected and delivered to a reprocessing facility. There, they are immersed in acid, then chemically processed to extract plutonium. When the “tails”—or the residual materials—contain less than about 2 percent plutonium, the process is stopped. It is not economically worthwhile to continue. The residue is put in containers and buried.

In the accounting-free Soviet Union, however, the process was very different. Every atom of plutonium was considered to be the fruit of socialist labor. Every gram was seen as adding to the superpower status of the empire. Cost was not a consideration. As a result, the Soviets continued their reprocessing until the tails contained only two hundred parts per million (0.02 percent) of plutonium. As a result, that whole vast reactor complex, from Mayak to Tomsk to Krasnoyarsk, was consuming billions of rubles of resources just to scrape the few last atoms of plutonium off the bottom of the barrel. There was no accounting system to say, “Stop!” Soviet plutonium ended up costing substantially more than in the U.S., and the Russian plutonium stockpile is substantially larger than we thought it was. This latter discovery has a significant impact on the negotiation of proposed strategic arms treaties and on our efforts to contain the terrorist threat. All for the lack of a set of books.

A VALUE-SUBTRACTING ECONOMIC MACHINE

Economists describe the operation of a business or similar enterprise as a “value-adding” process. A shoemaker acquires leather, adds his labor and the use of his equipment (capital) to produce shoes that (hopefully) have a value significantly in excess of the leather he started with. Unfortunately, it did not always work out that way in the Soviet Union. Most industries, operating without the benefit of any cost information or controls, turned out to be giant value-subtracting machines. They would start with perfectly good steel, rubber, and glass, and turn out refrigerators no one wanted.

The Economist summed up this phenomenon in 1992 when it first compared the free market value of Russia’s raw materials with the country’s gross national product. It found that if all the oil, gas, gold, iron, bauxite, etc., that Russia produced in 1992 had been sold on the world market, Russia would have earned about twenty-seven trillion rubles, at the then-effective conversion rate. Yet Russia’s GNP in 1992 was estimated to be only fifteen trillion rubles. Thus, the Soviet system was subtracting almost half the value of the raw materials produced before delivering products. The Soviet Union would have been better off (economically, but not politically) if it had shut down every industry but the extractive ones, sold its produced commodities on the world market, told the workers to go home, and sent their citizens a Kuwait-like welfare check.

A specific example was the Karl Zeiss Jena camera company. The prewar Zeiss firm had been located in Berlin. At the end of World War II it was split into East and West components. Forty years later, when the Wall came down, Zeiss/West looked into reacquiring that eastern Karl Zeiss Jena piece of the business. It found that for every eight deutsche marks of marketable product coming out of Zeiss/East, thirty deutsche marks of raw materials, parts, and labor were going in. Seventy percent of the input value was being subtracted before a product came out.

In Russia itself, the diamond-cutting and polishing shops in Moscow and elsewhere were turning out finished diamonds worth about half the value of the rough diamonds first produced at the mines. (This latter value is based on the DeBeers price paid for rough diamonds worldwide.) The numbers seem to be consistent. The Soviet system subtracted about half the value of the raw materials and labor fed into any of its industrial processes before turning out a product.

WE CASH THE SOVIET PEACE DIVIDEND

And so it came to pass that the Soviet empire collapsed. In a farewell 1991 Christmas telephone call, Mikhail Gorbachev advised the U.S. President that he was resigning his offices of president of the Soviet Union and commander in chief of its armed forces. “You can have a very quiet Christmas evening. . . . I am saying good-bye and shaking your hands.” With that, the Soviet Union was gone. In its place, the new Russian Federation began the painful reallocation of resources. The value-subtracting game stopped. Local managers began to optimize their operations based on economic reality. They also stripped their comrades of any ownership rights, but that’s another story, still unfolding.

The movement of bauxite and aluminum is an interesting example of what happened. In 1987 almost all (96 percent) of the aluminum produced in the Soviet Union went to domestic use. Only 4 percent made it to the export market. At that time the world price of aluminum was around $1.60 per pound. Then, in 1992, the value-subtracting stopped. The managers of bauxite mines and aluminum smelting facilities seized control of their own fates. They refused to ship aluminum to deadbeat manufacturers of useless refrigerators and unneeded fighter planes. Instead they began to export onto the world market, for cash. By 1993 the Russian Federation was exporting about half of its aluminum production. That provided welcome cash to those managers or their bankers on Cyprus, but it had another, grander effect. By 1993 the world price of aluminum, driven down by Russian exports, had dropped to sixty cents per pound. As a result, the cost of the aluminum in every western beer can, in every engine block, fell by a factor of almost three.

In the decade that followed the end of the Cold War, economists and pundits have wondered why the U.S. has suffered so little inflation. We have enjoyed one of the greatest economic booms of all time, yet inflation remained below 3 percent. Technology in general and the computer revolution in particular are given most of the credit, but I would like to suggest another contributor. We are cashing the Soviet “peace dividend.” That expression refers to the resources suddenly made available to a people when their government ends a military adventure. In the strange case of the Soviet Union, however, the reallocation of Soviet raw materials onto world markets has kept the lid on everyone’s commodities prices. The whole world has benefited.

IN HINDSIGHT, IT ALL BECOMES CLEAR

None of the above was obvious in 1982. Churchill earlier had described Russia as a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. Nowhere was that more true than when trying to plumb the Soviet economy during the dark years of the Cold War. As the 1980s dawned, graybeards in the West held to their view of the Soviet system as monolithic and stable, lumbering along toward eternal life on the backs of its exploited but complacent serfs. The newcomers to Washington felt differently, but they had a hard time proving their point. But they really did not have to, for one of the newest and most clear-sighted of their number was the seventy-one-year-old fortieth President of the United States. Ronald Reagan’s willingness to bet against the Soviet economy became clear at a meeting of the National Security Council in March 1982. While discussing the national security study he had entrusted to my care, the President began to ruminate about new approaches to the Soviet problem.

“Why can’t we just lean on the Soviets until they go broke?”

The cabinet-level elders around the table discouraged such thinking. It would not work. The Soviet Union was a stable monolith, etc. Henry Rowen spoke up from a back seat, along the wall, to disagree. Rowen and his outsider colleagues felt the Soviet economic system was on the verge of collapse. Reagan thanked Rowen for his support and then, with a mere nod of his head, said to me, “That’s the direction we’re going to go.”

Two years later, in late 1984, the Politburo gathered to review an extensive GRU study of the now widening gap between the American and Soviet economies. It was not a pretty picture. At a subsequent social gathering of the Soviet military establishment, attended and noted by the Hungarian ambassador to the Soviet Union, one general rose to toast “the need to push the nuclear button as soon as possible, before the imperialists can gain superiority over us in every field.” According to the ambassador: “The others . . . received their comrade’s insane words with great ovation.”

Pushing the Soviet Union to the brink of economic collapse was a gamble not without risk.