PERFECT PITCH:

Pitches That Never Fail

..................................

by Marc Acito

“A first-time novelist sets the record at a writers conference for the most pitches, leading to a multiple-book deal, awards, translations, excellent reviews and a movie option. An inspiring true success story, a literary version of Seabiscuit, except the horse is a writer.”

As pitches go, this one’s devoid of conflict, but that’s the point. This scenario actually happened to me. Hence my qualification for writing this article.

My writing students get nervous when I ask them to pitch their works-in-progress on the first day of class, particularly if they’re just starting. “I wouldn’t know how to describe it,” they say. “I don’t know what it’s about.”

A pitch is simply another story that you’re telling. A very, very short one.

And therein lies the problem. To some degree, we can’t know what our novel/memoir/screenplay/play/nonfiction book is entirely about until we’ve gotten it down. But I contend that thinking about the pitch ahead of time helps focus a writer’s goals for a piece. It’s not just a commercial concern, it’s an artistic one.

Writers are storytellers and a pitch is simply another story that you’re telling. A very, very short one. Rather than view pitching as if you were a salesman in a bad suit hawking used cars, imagine that you’re a pitcher for the Yankees and that the agent or editor is the catcher: They’re on your team, so they really want to catch the ball.

Or, put another way, you’re a different kind of pitcher, this one full of cool, refreshing water that will fill their empty glass.

But first you’ve got to get their attention.

THE HOOK

“I need something to grab me right away that tells me exactly why I should want to read this submission (of all the submissions on my desk),” says Christina Pride, senior editor at Hyperion.

A hook is exactly what it sounds like—a way to grab a reader like a mackerel and reel them in. It’s not a plot summary, but more like the ad campaign you’d see on a movie poster. Veteran Hollywood screenwriter Cynthia Whitcomb, who teaches the pitching workshop at the Willamette Writers Conference in Portland, Oregon, recommends that writers of all genres start with a hooky tagline like this one from Raiders of the Lost Ark:

“If adventure had a name, it’d be Indiana Jones.”

That’s not just first-rate marketing, it’s excellent storytelling.

Here are some of my other favorite taglines for movies based on books, so you can see how easily the concept works for novels:

- “Help is coming from above.” (Charlotte’s Web)

- “From the moment they met it was murder.” (Double Indemnity)

- “The last man on earth is not alone.” (I am Legend)

- “Love means never having to say you’re sorry.” (Love Story)

The last one actually isn’t true; love means always saying you’re sorry, even when you’re not, but the thought is provocative and provocation is exactly what you want to do.

When I pitched my first novel, How I Paid for College, I always started the same way. First, I looked the catcher right in the eye (this is very important—how else are they going to catch the ball?). Then I said,

“Embezzlement. Blackmail. Fraud…High School.”

I began my query letters the same way.

“I always begin my proposals with a question,” says Jennifer Basye Sander, co-author of The Complete Idiots Guide to Getting Published. “I want to get an editor nodding their head in agreement right away.”

No, you’re not asking something like, “Are you ready to rock ‘n roll?” but instead an open-ended conversation starter like, “Can you be forgiven for sending an innocent man to jail?” (Ian McEwan’s Atonement) or “What does it take to climb Mount Everest?” (Jon Krakauer’s Into Thin Air). Particularly useful are “what if?” questions like “What if an amnesiac didn’t know he was the world’s most wanted assassin?” (Robert Ludlum’s The Bourne Identity) or “What if Franklin Delano Roosevelt had been defeated by Charles Lindbergh in 1940?” (The Plot Against America, Philip Roth).

Acito employs humor in his novels, but there’s nothing funny about the effectiveness of his pitches.

The same also holds true for nonfiction. If you sat down in front of an agent and asked, “What if you could trim your belly fat and use it to fuel your car?” trust me, they’d listen. Questions like that make the catcher want to know more. Which is exactly what you do by creating…

THE LOG LINE

No, it’s not a country western dance done in a timber mill. And without realizing it, you’re already a connoisseur of the genre, having read thousands of log lines in TV Guide or imdb.com or the New York Times Bestseller List. A log line is a one-sentence summary that states the central conflict of your story. For example:

“A teen runaway kills the first person she encounters, then is pursued by the dead woman’s sister as she teams up with three strangers to kill again.”

Recognize it? That’s The Wizard of Oz.

Here’s another:

“The son of a carpenter leaves on an adventure of self-discovery, rejects sin, dies and rises again transformed.”

Obviously, that’s Pinocchio.

Okay, seriously, here’s the one I did for How I Paid for College:

“A talented but irresponsible teenager schemes to steal his college tuition money when his wealthy father refuses to pay for him to study acting at Juilliard.”

It’s not genius, but it captured the story succinctly by identifying the protagonist, the antagonist, and the conflict between them. In other words, the essential element for any compelling story.

AND HERE’S THE PITCH…

Pitches are often referred to as “elevator pitches” because they should last the length of your average elevator ride—anywhere from 30 seconds to two minutes. Or, for a query letter, one page single-spaced. That’s about 350 words, including “Dear Mr. William Morris” and “Your humble servant, Desperate Writer.”

Essentially, the pitch is identical to a book jacket blurb: it elaborates on the set-up, offers a few further complications on the central conflict, then gives an indication of how it wraps up. When it comes to the ending, “don’t be coy,” says Erin Harris, a literary agent at the Irene Skolnick Agency in Manhattan. “Spoil the secrets, and let me know what really happens.” Agents and editors want a clear idea of what kind of ride they’re getting on before investing hours in your manuscript. Make it easy for them to do their jobs selling it.

Agents and editors want a clear idea of what kind of ride they’re getting on before investing hours in your manuscript.

Nowhere was this clearer to me than when I read the jacket copy of my first novel and saw that it was virtually identical to my query letter.

Indeed, your best practice for learning how to pitch is to read jacket descriptions (leaving out the part about the author being a “bold, original new voice”—that’s for others to say).

Or think of it as a very short story, following the structure attributed to writer Alice Adams: Action, Backstory, Development, Climax, End.

It’s as easy as ABDCE.

“The best queries convey the feeling that the author understands what the scope, structure, voice, and audience of the book really are,” says Rakesh Satyal, senior editor at HarperCollins to authors such as Paul Coelho, Armistead Maupin and Clive Barker. “To misunderstand or miscommunicate any of these things can be truly detrimental.”

That’s the reason we often resort to the Hollywoody jargon of it’s “This meets that,” as in “It’s No Country for Old Men meets Little Women.” Or it’s…

- …Die Hard on a bus (Speed)

- …Die Hard in a plane (Con Air)

- …Die Hard in a phone booth (Phone Booth)

- …Die Hard in a skyscraper (no, wait, that’s Die Hard).

ACITO’S ORIGINAL QUERY

HOW I PAID FOR COLLEGE

A Tale of Sex, Theft, Friendship and Musical Theater

A novel by Marc Acito

Embezzlement…Blackmail…Fraud…High School.

How I Paid for College is a 97,000-word comic novel about a talented but irresponsible teenager who schemes to steal his college tuition money when his wealthy father refuses to pay for acting school. The story is just true enough to embarrass my family.

It’s 1983 in Wallingford, New Jersey, a sleepy bedroom community outside of Manhattan. Seventeen-year-old Edward Zanni, a feckless Ferris Bueller type, is Peter Panning his way through a carefree summer of magic and mischief, sending underwear up flagpoles and re-arranging lawn animals in compromising positions. The fun comes to a screeching halt, however, when Edward’s father remarries and refuses to pay for Edward to study acting at Juilliard.

In a word, Edward’s screwed. He’s ineligible for scholarships because his father earns too much. He’s unable to contact his mother because she’s off somewhere in Peru trying to commune with the Incan spirits. And, in a sure sign he’s destined for a life in the arts, Edward’s incapable of holding down a job. (“One little flesh wound is all it takes to get fired as a dog groomer, even if you artfully arrange its hair so the scar doesn’t show.”)

So Edward turns to his loyal (but immoral) misfit friends to help him steal the tuition money from his father. Disguising themselves as nuns and priests (because who’s going to question the motives of a bunch of nuns and priests?) they merrily scheme their way through embezzlement, money laundering, identity theft, forgery and blackmail.

But along the way Edward also learns the value of friendship, hard work and how you’re not really a man until you can beat up your father. (Metaphorically, that is.)

How I Paid for College is a farcical coming-of-age story that combines the first-person-smart-ass tone of David Sedaris with the byzantine plot twists of Armistead Maupin. I’ve written it with the HBO-watching, NPR-listening, Vanity Fair-reading audience in mind.

As a syndicated humor columnist, I’m familiar with this audience. For the past three years, my bi-weekly column, “The Gospel According to Marc,” has appeared in 18 alternative newspapers in major markets, including Los Angeles, Chicago and Washington, DC. During that time I’ve amassed a personal mailing list of over 1,000 faithful readers.

How I Paid for College is a story for anyone who’s ever had a dream…and a scheme.

www.MarcAcito.com

(503) 246-2208

Marc@MarcAcito.com

5423 SW Cameron Road, Portland, OR 97221

“I appreciate when agents and authors offer good comp titles,” confirms Hyperion’s Christina Pride. “It’s good shorthand to help me begin to position the book in my mind right from the outset in terms of sensibility and potential audience.”

Agent Erin Harris agrees. “For example,” she says, “the premise of one book meets the milieu of another book.” As in Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, an idea I will forever regret not thinking of myself.

When citing comp titles, be certain to invoke the most commercially successful and well-known works to which you can honestly liken yourself. No agent wants to earn 15 percent of Obscure Literary Title meets Total Downer by Author Who Committed Suicide.

So I steered clear of my lesser-known influences and focused on the big names, saying, “How I Paid for College is a farcical coming-of-age story that combines the first-person-smart-ass tone of David Sedaris with the byzantine plot twists of Armistead Maupin.”

That line also made it onto the jacket copy.

My book hasn’t changed, but I continue to update the pitch as I develop the movie. What started as “Ferris Bueller meets High School Musical,” turned into “A mash-up of Ocean’s 11 and Glee.” By the time the movie actually gets made it’ll be “iTunes Implant Musical Experience meets Scheming Sentient Robots.”

“A word of caution,” Harris adds. “Please do not liken your protagonist to Holden Caulfield or your prose style to that of Proust. Truly, it’s best to steer clear of the inimitable.”

Speaking of the inimitable, while the titles of Catcher in the Rye and Remembrance of Things Past are poetically evocative, they wouldn’t distinguish themselves from the pack in the Too-Much-Information Age. Nowadays, your project is competing for attention with a video of a toddler trapped behind a couch. (I’m serious, Google it, it’s got all the makings of great drama: a sympathetic protagonist, conflict, complications, laughter, tears and an uplifting ending. All in two minutes and 27 seconds.)

So while it’s not a dictum of the publishing industry (though, given the nosedive the industry has taken, what do they know?), I think 21st century writers would do well to title their works in ways that accommodate the searchable keyword culture of the Internet.

In other words, To Kill a Mockingbird was fine for 1960, but if you tried promoting it today, you’d end up at the PETA website.

Like the logline, the catchiest titles actually describe what the book is about. Consider:

- Eat, Pray, Love

- Diary of a Wimpy Kid

- Sh*t My Dad Says

- A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

In those cases, the title is the synopsis. Similarly, some titles, while less clear, include an inherent mystery or question:

- Sophie’s Choice

- The Hunger Games

- And Then There Were None

- The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

Lastly, even if the reader can’t know automatically what the title means, it helps if it’s simple and memorable, like:

- Twilight

- Valley of the Dolls

- The Thorn Birds

- Captain Underpants

One way to tell if you’ve got an effective title is to submit it to the “Have you read…?” test. If it feels natural coming at the end of that sentence, you’re on the right track.

Granted, straightforward titles are easier if you’re writing nonfiction like Trim Your Belly Fat and Use it to Fuel Your Car. As is the final part of the pitch.

BUILDING A PLATFORM

Along with branding, platform is one of the most overused buzz words of the last decade. “If you are writing nonfiction,” Erin Harris says, “it’s important to describe your platform and to be a qualified expert on the subject about which you’re writing”

In other words, if you’re going to write Teach Your Cat to Tap Dance you better deliver a tap-dancing cat, along with research about the market for such a book.

For first-time novelists this can prove challenging. But Harris says that every credit truly helps: “If you have pieces published in literary magazines, if you have won awards, or if you have an MFA, my interest is piqued.”

That last advice should also pique the interest of every fledgling writer out there. In my case, what actually got me an agent wasn’t just the pitch, it was the fact that I met best-selling novelist Chuck Palahniuk at a workshop and he’d read a column of mine in a small alternative newspaper. Ultimately, it’s not about who you know, it’s about who knows you. So publish wherever you can. You never know who’s reading.

Write on.

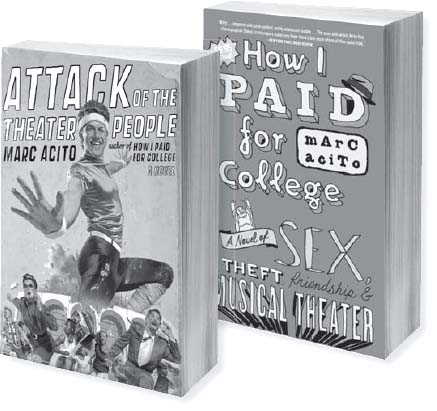

MARC ACITO is the award-winning author of the comic novels How I Paid for College and Attack of the Theater People. How I Paid for College won the Ken Kesey Award for Fiction, was a Top Teen Pick by the American Library Association and is translated into five languages the author cannot read. A regular contributor to NPR’s All Things Considered, he teaches story structure online and at NYU. www.MarcAcito.com