Between February 7, when what would become known as Grierson’s Raid was proposed, and its execution in mid-April, a plan evolved for the raid. It was the result of a collaboration of several levels of command. Grant provided the strategic focus of the raid, and the timing of its beginning. He wanted the Southern Railroad cut between Meridian and Jackson, and he wanted it cut a week before he began moving the Army of the Tennessee across the Mississippi River. This would not only delay supplies from reaching Vicksburg prior to its investiture, but would also distract Confederate attention at a critical time, and prevent Pemberton from reinforcing any troops opposing Grant’s landing.

When the raid was first proposed, its effects on Vicksburg were almost secondary. At that time Grant intended to swing south first after landing in central Mississippi to capture Port Hudson. Then the Army of the Tennessee, reinforced by General Nathaniel Banks’ Army of the Gulf would move north to Vicksburg. The joint army would be supplied via the Mississippi River. General Bank’s dilatoriness forced Grant to revise his plan to the one executed in 1863, but that change occurred after the raid began. It did not alter the raid’s strategic objectives however.

Turning a strategic objective into a practicable operation was a challenge. Actual planning for the raid was split between Hurlbut, Sooy Smith, commanding the cavalry division, and Benjamin Grierson, the raid commander. The plan that resulted was primarily Grierson’s, with Hurlbut and Smith providing such resources that fell outside a cavalry brigade.

The 1860 model light cavalry saber issued to Union cavalry in the American Civil War. (US Army Heritage and Education Center)

Grierson’s brigade was stationed at La Grange, Tennessee, well north of the Southern Railroad of Mississippi. Reaching the railroad would require an overland penetration some 250 miles, deep into Mississippi. Today that distance can be traveled in five hours by automobile. On horseback, a mounted formation would account itself fortunate to reach that distance in five days, especially given the primitive roads in mid-19th-century Mississippi.

Traveling by road in enemy territory invites both attention and ambush. Avoiding roads whenever possible made a raiding force less detectable and less predictable, especially during the approach to the objective. Avoiding roads was safer, but took longer. A minimum of a week’s hard ride was allocated to reach the Southern line. That meant the raid should start two weeks before Grant’s intended crossing date.

The size of the raid and the forces to be employed were next determined. Grant originally envisioned committing Grierson with 500 men, and felt that the Sixth Illinois by itself was sufficient. Hurlbut and Grierson, with Smith’s concurrence, increased the raiding force to include all of Grierson’s current command, the First Brigade of the Cavalry Division. That gave Grierson a force of 1,750 cavalry troopers. The capabilities of these individual troopers were critical to the raid, and carefully considered in its planning. For combat, each cavalryman was equipped with a carbine, a revolver, and a saber.

The two Illinois regiments and four companies of the Second Iowa used Sharps carbines, a standard Union cavalry carbine. It was 39½ inches long (1.003 meters), weighed eight pounds (3.629kg) and fired a .52-caliber (.535 inches or 13.6mm) bullet. It was breech-loading and rifled. The Sharps made before and during the Civil War had a vertical sliding breechblock. They used paper cartridges, but could be loaded with black powder if the user lacked cartridges. However, this ability to use loose powder was balanced by the size of the round. A standard infantry musket of the day fired a .58-caliber round, which would not fit in a Sharps barrel.

Because they were breech-loading, Sharps rifles could be fired prone, from behind cover or from horseback. The primer was built into the cartridges so firing it was as simple as sliding the cartridge into the chamber, closing the breech, aiming the rifle, and pulling the trigger. An experienced cavalryman – and after a year of combat, Grierson’s men were experienced – could fire ten rounds a minute. The Sharps had a range of about 1000 yards. Stephen Forbes, when a private in the Seventh Illinois, wrote home stating that he could kill a man “at half a mile” with his. While this was theoretically possible, its effective range was more likely to be 300 yards.

Six companies of the Second Iowa used the Colt Repeating Carbine, a rifle-length version of the Colt six-shooter. The army version hit the market in 1855. Colt made several varieties of the rifle, including carbines. The Second Iowa most likely had the .44-caliber version. If so, they could use the same ammunition for both their carbines and their pistols. The .44-caliber Colt Repeating Carbine had six cylinders and a barrel that was around 32 inches (0.812m) in length. It weighed a little over seven pounds (3.18kg).

The Colt Carbine was not a breech-loader. Like the Colt pistols, it used a paper cartridge, loaded from the front of the cylinder. Reloading was involved and time-consuming, unsuited to a hot firefight. In some units soldiers paired off in combat, with one man firing one carbine while another reloaded the second.

Each cylinder had to be carefully sealed with grease when reloading, or risk a shot causing the other bullets to fire simultaneously. Since the left hand supported the barrel ahead of the cylinder, this type of misfire shot the user’s fingers off. The Colt was also delicate, a combination that led to the regular army rejecting the weapon, and its unpopularity with some soldiers. However, as a repeating rifle it gave users a lot of firepower, and obviously several hundred had been available when the regiment was forming.

Despite its short length of carbines, the Colt was often awkward to fire while mounted and on the move. For that, a cavalryman carried a pistol, and there were a variety of these used by Union cavalry forces. It is likely that the men in Grierson’s brigade were issued with some version of the Colt Army Revolver, a .44-caliber pistol with six cylinders. While some troopers may have had different pistols, the ones they were most likely to have been issued with were either the 1848 Colt Dragoon or the 1860 Colt Army Model. The army purchased 127,000 1860 Army Colts, most during the Civil War.

The Dragoon weighed 4 pounds 4 ounces (1.93kg) and was 14¾ inches (374mm) long, with a 7½-inch (190mm) barrel. The 1860 Colt weighed 2 pounds 11 ounces (1.22kg), and had a 14-inch (355.6mm) overall length when fitted with the standard 8-inch (203mm) barrel. Both fired a .44-caliber bullet that weighed nearly a third of an ounce (9.4g), and was accurate to about 100 yards. The gun also used a paper cartridge, loaded from the front of the cylinder. A loaded revolver could be fired six times in as little as six seconds. Again, reloading the pistol was an involved and time-consuming process, unsuited to a firefight. Experienced troopers were therefore sparing with fire, preferring to make each shot tell as opposed to firing for effect. While soldiers were issued one revolver, some obtained a second – just in case.

Finally, a cavalryman had a saber. While many Eastern cavalry units soon discarded their sabers, the Western cavalry kept theirs. The saber was better as a weapon of intimidation than for any real military utility. It was harder for inexperienced troops to stand up to the swinging edge of a saber than the muzzle of a revolver. The threat offered by the saber seemed more personal. Experienced infantry was less likely to be cowed, but no smart cavalryman wanted to charge experienced and prepared infantry, anyway.

By 1863, there were two versions of the saber issued to Union cavalry – the Model 1840 cavalry saber and the Model 1860. The 1840 saber was 44 inches (1.12m) long, with a 35-inch (0.89m) blade, and weighed six pounds (2.72kg). The 1860 saber, known as the “light” cavalry saber, was 41 inches (1.04m) long, with a 33-inch (0.84m) blade that was 1 inch in width. It weighted 3 pounds 9 ounces (1.70kg). Both had curved blades, with the sharpened edge on the convex side, and were intended as slashing weapons.

The 1860 saber, significantly lighter and handier than the earlier model, was better adapted to cavalry fighting during the Civil War. It had only just gone into production when the three regiments in Grierson’s brigade were raised, so these men were probably initially issued one of the 24,000 1840 sabers manufactured before they ceased production in 1858. The Seventh Illinois almost certainly was equipped with the 1840 sabers, as the regiment had been raised as a result of an arms dealer selling the army sabers that he had found forgotten in a Missouri armory. A photograph of Stephen Forbes taken in 1861 shows him posing with an 1840 saber. However, it is likely that troopers took the opportunity to replace the “wristbreaker” 1840 sabers with the lighter 1860 model.

A horse gave a cavalryman mobility. By 1863 most fighting was done dismounted, especially against infantry. Mounted confrontations generally occurred only when cavalry met cavalry, or when attacking militia and unprepared infantry. If you caught enemy soldiers in camp or on the march, or encountered a baggage or supply train, you charged mounted, depending upon pistol and saber. Otherwise, you dismounted and fought behind cover, taking advantage of the ability to reload a breech-loader while lying down.

There was a chronic shortage of suitable cavalry mounts in the armies of the Tennessee and Cumberland in the first half of 1863. Grierson had more troopers than horses, and the horses that his men did have were often unsatisfactory – spavined, blown, or infirm. While his regiment had received a draft of horses in March, most were unsatisfactory. As a result, many men were mounted on inferior horses. Other troopers rode into Mississippi mounted on Tennessee mules – one creature of which the state had a sufficiency. Grierson was not unduly worried about the available horseflesh. Horses were bred in Mississippi, especially northern Mississippi. Grierson knew that by the time the brigade reached its goal all of his men would be adequately mounted – courtesy of those in rebellion against the United States.

To further increase the chances of success, Battery K of the First Illinois Artillery was added to the raid. It was a horse artillery unit, equipped with six light Woodruff guns. These guns were among the most unusual pieces of ordinance in the Union Army. They were intended as “galloper guns” – field pieces to accompany mounted cavalry. The barrel weighed just 256 pounds (116kg), and it had a 2-inch (50mm) bore. The guns fired a conical 2-pound (0.9kg) lead round. It was a sort of oversized Minié ball. Alternatively, the gun could be loaded with cased 1-ounce (28g) lead shot.

The gun was mounted on a special carriage made by a manufacturer of civilian buggies and wagons in Quincy, Illinois, which also made the caissons. The piece was light enough to keep up with cavalry when pulled by two horses. The carriage was fragile though, and tended to break under hard usage.

They were the invention of James Woodruff, an Illinois manufacturer with dreams of achieving martial glory through ordinance. Feeling that the army lacked an artillery piece suitable as horse artillery, he filled the gap with this iron gun – to be manufactured at his Quincy, Illinois, factory. The army turned down the new weapon however. It weighed more than the existing brass 12-pound (5.4kg) howitzer and had only three-quarters the range of that piece. Further, it used non-standard ammunition that would complicate logistics.

UNION CAVALRYMAN

Grierson believed in traveling light. The troopers that accompanied his raid were equipped as seen here 1 . A bare minimum of kit was carried: their personal weapons, five days rations including double salt (with the understanding that the rations were to last ten days), and forty rounds of ammunition per firearm. In addition to their carbine and pistol, the troopers carried a saber. The Sixth and Seventh Illinois and part of the Second Iowa were equipped with Sharps cabines 2 . The rest of the Second Iowa carried Colt’s Revolving Rifles 3 .

Woodruff was well connected politically within the Illinois Republican Party and used his influence with Abraham Lincoln to get the decision reversed. Woodruff also sweetened the pot by offering to sell the army 9,000 sabers, 1,500 Colt revolvers, and 1,500 carbines that he had located, if he received a contract to manufacture the Woodruff gun. The army’s need for cavalry weapons was great and the cost of a limited number of Woodruff guns was trivial. So the army signed a contract for a trial order of 30 guns in 1861. If the guns proved useful more orders would follow. If not, the army received enough weapons to outfit an additional cavalry brigade.

The Army Ordinance Board’s assessment of the gun’s utility proved accurate. Woodruff’s guns were useful so long as there was no other artillery in the field. The 30 guns delivered were scattered among various Iowa, Illinois, and Missouri regiments. Their value proved limited, one battery using its Woodruff guns as carts with which to remove their dead from the battlefield. But Grierson saw something in the guns, and wanted them along. As it turned out, they proved highly useful during the course of the raid.

The next issue was where to cut the line. A major objective of the raid was to serve as a distraction. Anonymously destroying a length of track in the Mississippi countryside, and slipping away silently, would not achieve that goal. A town along the route would be the best objective. Hitting a town would not only offer an opportunity to destroy track, but also the depot facilities associated with a railroad. Locomotives needed water and fuel to run, and got both at small stations along the route.

The six Woodruff guns that accompanied the raid provided critical support at decisive points in the raid. This Woodruff gun is a park monument in an Illinois city today. Its carriage is not the same type used with Woodruff guns during the Civil War, but rather the standard Civil War artillery carriage. (Photo courtesy Jim Bender)

Meridian was possibly garrisoned, and a larger town than desirable for a raiding brigade. It was a possibility, but not a good first choice. Other options included Hickory, Newton, Lake, Forest, and Morton – all whistlestop villages along the Southern Railroad. Newton and Forest were the best choices of these, as they were scheduled watering spots for the steam locomotives. Newton had an additional advantage, as it was closer to the north–south Gulf and Ohio Railroad.

While Grierson’s primary objective was the Southern, disabling the Gulf and Ohio would also be beneficial. It was also a natural target for a Union cavalry raid – more so than the more distant Southern. Moving parallel to the Gulf and Ohio as he drove into Mississippi achieved two things: it gave Grierson’s Confederate opponents a focus for their attention that was removed from his actual goal; and, if Grierson got lucky, he might get an opportunity to actually hit the Gulf and Ohio, as well as the Southern. Newton became Grierson’s principal objective as a result.

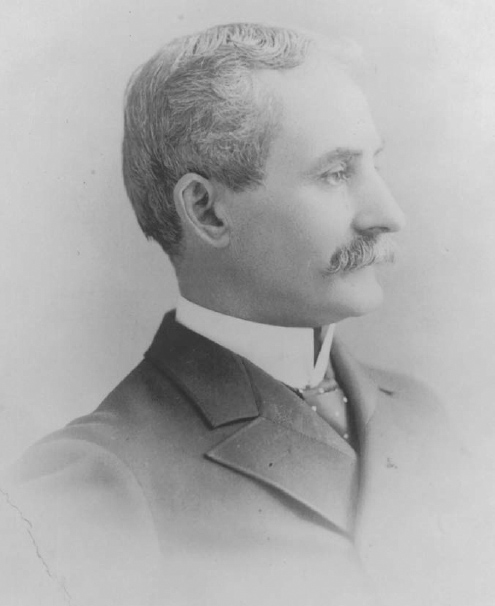

Sooy Smith was Grierson’s immediate superior at the start of the raid, and led one of the diversionary raids that helped Grierson penetrate deep into Mississippi. He is show here in a postwar photograph. (LOC)

A rough outline of an approach route began to coalesce. Grierson’s route would run from La Grange, Tennessee to Pontotoc, Mississippi. At that point it would appear to be a standard Union cavalry scout of northern Mississippi, possibly with an attempt to collect Confederate horses. This was a good way to disguise the ultimate purpose of the raid. Union cavalry in western Tennessee was chronically short of good mounts in early 1863. Northern Mississippi was one of the Confederacy’s sources of mounts. Remounting Union horsemen on Confederate mounts simultaneously strengthened the Northern armies while weakening the Confederacy’s cavalry.

Grierson’s superiors had other plans to disguise his intentions. The Army of the Tennessee would launch two other scouts on the same day that Grierson started his raid. Sooy Smith would lead one raid, taking command of some 1,500 men from five infantry regiments, supported by artillery. This column would push into northwest Mississippi from La Grange along the route of the Mississippi Central Railroad. A second force, with 1300 men, would advance into Mississippi from Memphis along the Mississippi and Tennessee Railroad.

These raids were to be short, shallow penetrations into Mississippi. While the infantry in the two supporting raids could not hope to catch Chalmers’ fast-moving cavalry, these two pushes – seemingly converging at Granada, where the two railroads met – would focus Chalmers’ attention on the threat posed to Vicksburg by an offensive down the Mississippi Central axis. It might even draw Loring’s forces north, away from both Grand Gulf and Newton.

The Confederates would also be prevented from concentrating on a single Union effort; they had to counter all three raids. Each raid, including Grierson’s critical effort, would face less opposition than it would if only one penetration were attempted. Three raids would split the attention of Confederate forces in northern Mississippi. Flooding the zone with Union forces along a broad front increased the probability that Grierson and his men could slip south undetected amid the confusion.

There would be a further distraction to Confederate attentions. General Rosencrans, commanding the Army of the Cumberland in central and eastern Tennessee, planned his own raid into Confederate soil. Led by Colonel Abel Streight, it was to sweep through northern Alabama and Georgia. The two armies decided to coordinate the start of both raids to further divide the attention of Confederate cavalry.

Once Grierson was past the screening Confederate cavalry, he could stay ahead of them by riding hard and fast. No other Confederate cavalry would be between Grierson and the Southern Railroad. Grierson would cut south through Mississippi, roughly following a line from Pontotoc, through Houston, Starkville, Louisville, Philadelphia, and Decatur to Newton. Along the way Grierson could make lunges east, against the Gulf and Ohio. If he encountered resistance, he would continue south. If he did not, he would destroy track on the Gulf and Ohio. Either way, he got closer to his real goal.

This route was only an outline. Circumstances could force alterations. If he got ahead of his opposition, he would take to the roads and race south. If he ran into trouble, he would break contact, probably by going to the west, and then ride cross country. If he found a welcoming committee in the form of regular infantry in one of the towns – including Newton – he would break off and hit the railroad where Confederate troops were not.

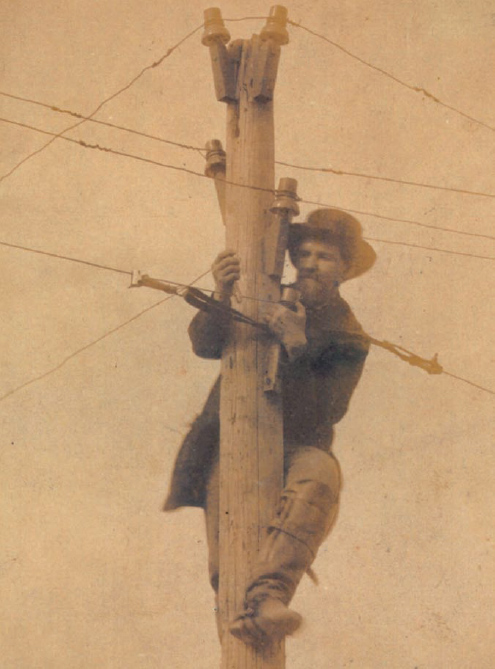

Along the way he would destroy any bridges he crossed, if this could be done without incurring a significant delay. In the short term this would slow pursuit of Grierson’s brigade. In the long run, it would make moving troops through Mississippi more difficult until the bridges were repaired. This would slow any reaction against Grant. Finally, Grierson’s men would cut any telegraph lines they encountered. It only took a few minutes’ work to pull down a line and cut a length of wire. That cut communications, delaying pursuit and sowing confusion.

Taking the cut wire away and disposing of it at a remote location – preferably in a river or pond – further delayed repair of the telegraph line. It would not be enough for a repair crew to locate the break – difficult enough when a line ran through miles of swamp, woods, or fields – and splice it. A repair crew would have to replace the missing line. By 1863 telegraph line was a scarce commodity in the Confederacy.

Once at Newton – or whatever town the raiders ultimately reached – the cavalrymen would do as much damage to track and town as time permitted. There were strict rules as to what could or could not be deliberately destroyed. Most government buildings were fair game, although medical facilities such as hospitals were exempt. Industrial buildings with military application could also be destroyed.

This rule had a wider scope than those buildings devoted to the production of weapons. A shoe factory or clothing mill could be burned because it could supply uniforms to the army. Whether or not that plant had actually sold goods to the military, it could in the future. Any metalworking or blacksmith’s shop was a legitimate target because of its potential to repair or produce weapons. So were any buildings or facilities associated with a railroad, due to the extensive military use of them. Stocks of food and fodder beyond the level of personal subsistence were also fair game, to deny their use to enemy armies.

There were limits. A hotel used as a barracks could be burned, but not typically a private dwelling. Personal property was supposed to be inviolate. Government mails were legitimate booty, but personal mail was supposed to be left alone. Livestock and vehicles could also be taken as they had military value.

In 1863 livestock included human beings – black slaves. Slaves were still considered property in the United States. However, slaves owned by those in rebellion against the United States had been considered “contraband of war” since May 1861, because slave labor could be used to aid the rebellion. The Emancipation Proclamation, which came into force on January 1, 1863, went further, declaring slaves in territories in rebellion against the United States as free men. However, except where Union forces – such as a raiding cavalry brigade – could enforce it, the proclamation was a dead letter in those territories.

These rules were frequently more honored in the breach than in observance during the Civil War, and cavalrymen were notorious for “foraging” forbidden items – money, watches, jewelry, and other valuables – from civilians, and burning down civilian barns and homes. Grierson intended to follow these rules. There was a large dose of self-interest in his doing so. His success depended upon speed, and cavalrymen overloaded with plunder could not move quickly. An acquiescent population secure in their property if they left the raiding troopers alone was less likely to hinder Grierson’s movements than a people outraged at having their homes torched.

Telegraph lines were vital to communications and vulnerable to damage. Grierson’s raiders rarely had time to chop down or damage telegraph poles, but they frequently cut long lengths of wire, and dumped the cut wire into ponds or streams. (LOC)

Another consideration was a desire not to unduly alienate the civilian population. There was believed to be significant Union sentiment in rural Mississippi and several of the rural counties had voted against secession in 1861. Grierson hoped to fan that loyalty into renewed support for the United States by using a gentle hand.

Finally, there was a time factor. Destruction took time. Grierson planned on stopping at Newton – or whatever his objective proved to be – for the minimum possible time. He planned for no more than twelve hours, and that was barely long enough to destroy legitimate military contraband. Grierson wanted to do all of the damage he could in as short a period, and leave.

That left the final and fuzziest part of the raid’s plan – the withdrawal. At that point, if everything went as planned, Grierson and his men would be deep in Mississippi. Once Grierson’s presence was known, he could expect Confederate units throughout Mississippi to converge upon him. And, in these days before radio, he had no way of getting help from Union forces upon his return. He would be strictly on his own.

The least likely way out would be the way he came. To the north would be a string of angry Mississippi civilians and Confederate soldiers stirred up by his passage. Instead the plan called for Grierson to cut east, south of Meridian, cross into Alabama, and then hook through the northwest corner of Alabama. From there he could slip back into Mississippi around Corinth, and then back to Tennessee and home. One advantage of this plan was that it provided yet another crack at the Gulf and Ohio Railroad.

Alternatively he could ride west and south to Grand Gulf or Port Hudson. By the time Grierson and his men were approaching the Mississippi, Grant would be ashore, and he and Grierson could rendezvous. The risk in this approach lay in the uncertainty of knowing exactly when and where Grant would land. There was also a sizable Confederate garrison at Grand Gulf and circumstances could delay Grant. If so, Grierson could get pinned between hostile Confederate forces at Grand Gulf and the Mississippi River, or get trapped between Grand Gulf and Confederate forces transferred from Jackson or Vicksburg. To reach Grand Gulf or Port Gibson from Newton would require a ride of 150 miles or so, as Grierson would have to take a roundabout path to avoid Jackson and Vicksburg.

Another possibility was to ride to Natchez, take the town, and depend upon the navy to evacuate the brigade. It could be done, as there was no permanent garrison in Natchez. The problem was attracting the attention of the navy with enough time to organize a mini-Dunkirk before the Confederates could crush Grierson’s brigade.

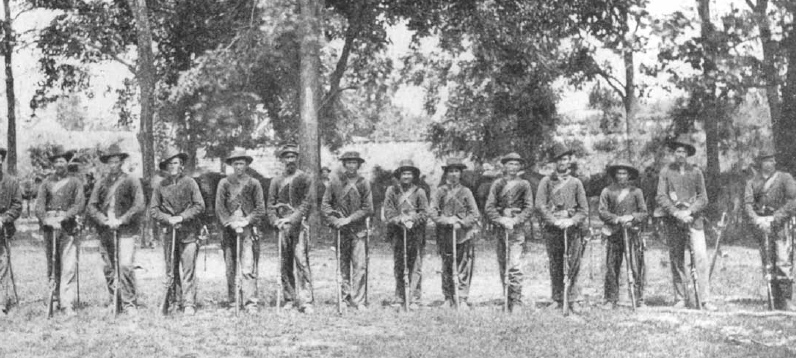

Soldiers of the Second Tennessee Cavalry Regiment. This unit was part of Clark Barteau’s command that chased Grierson’s brigade to Houston, Mississippi, and then was decoyed into following Hatch’s Second Iowa north. (AC)

A final route was one that was then considered the least likely – continue southwest through Mississippi and into Louisiana. From there, Grierson and his men could link up with Nathaniel Banks’ Department of the Gulf. The route was long, and there were the dangers associated with making contact with the Union army – a different army than Grant’s. Grant was holding knowledge of the raid closely due to security concerns. The closest large Union garrison was at Baton Rouge. This was another 200 to 250 miles, depending upon how circuitous Grierson made the path.

Grierson’s superiors were sympathetic to the problems associated with his escape. The orders they issued essentially gave Grierson permission to do whatever he wanted, and take whichever path looked most promising for escape. Smith also planned a series of cavalry and infantry sweeps across northern Mississippi a week after he heard that Grierson had reached the Southern Railroad, in the hope that it might aid Grierson’s escape.

Regardless of how he got in and got out, Grierson planned on moving fast and that meant traveling light. The brigade went on the raid with a bare minimum of equipment. Every excess piece of kit was left at La Grange. Troopers brought their weapons, 40 rounds of ammunition for their carbines and revolvers, oats in the feedbags for the mounts, five days’ rations in haversacks for the men, and a double ration of salt. Everyone was made to understand that rations were to last ten days.

Grierson intended to feed his mounts and men off the land, and to collect as many remounts as possible, seizing food, fodder, and horses from those Mississippians supporting the rebellion. Grierson had no plans to carry away either wagons or (despite his abolitionist sympathies) runaway slaves for fear that these items would slow his progress. Similarly, Grierson intended to avoid combat as much as possible, riding around trouble whenever it was an option. Forty rounds per firearm could be expended in two hot engagements, leaving him unarmed deep in enemy territory without means to fight his way out.

To navigate, Grierson had two items – a pocket compass and Colton’s pocket map of Mississippi. Afterward he noted that Colton’s map “though small, was very correct.”