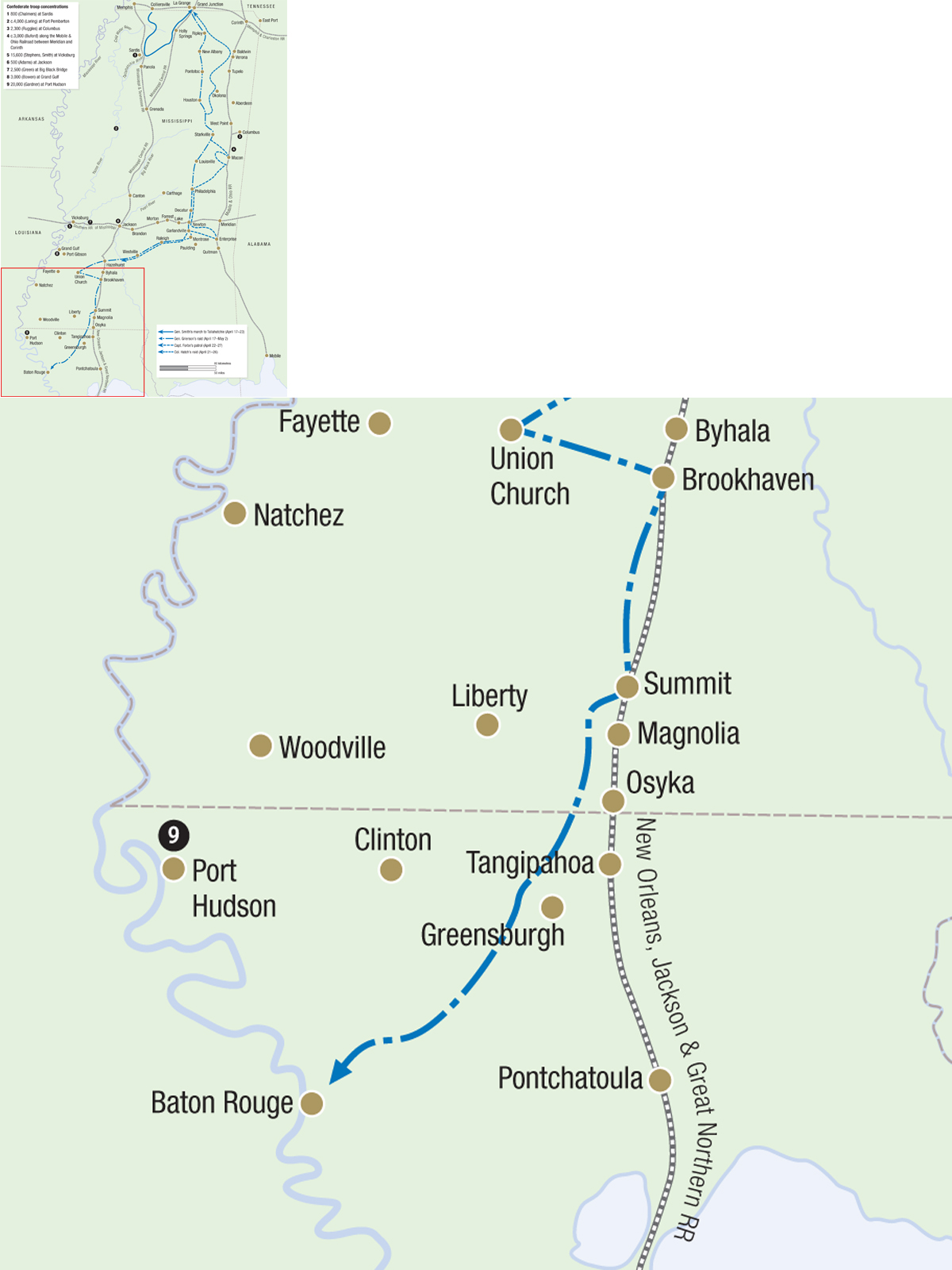

Grierson almost missed the raid he planned, as it was delayed with Grant’s offensive. As the Mississippi Raid continued to hang fire, Grierson applied for overdue home leave. On April 3 he was ordered to carry dispatches to Springfield, Illinois, allowing him to visit his home. Grierson was in Jacksonville, Illinois, when Hurlbut ordered Sooy Smith to prepare to launch the raid. Hurlbut telegraphed Grierson to return at once. Grierson did so, arriving in Memphis at midnight on April 17. Hatch had the brigade mounted and ready to go at 3:00 am. Had Grierson been any later, the resulting effort might have become “Hatch’s Raid.”

The actual departure was delayed because Smith wanted to confer with Grierson. In addition to cutting the Southern Railroad, Smith gave Grierson verbal instructions to use one regiment to cut the Mississippi Central near Oxford, and a second to cut the Mobile and Ohio near Tupelo, with the usual caveat of “if practicable.” Grierson’s brigade and supporting artillery rode out of La Grange at dawn, heading southeast. The men had gathered through barracks telegraph that they were “going on a big scout to Columbus, to play smash with the railroads.” The only two members of the raid that knew the actual objective and plan were Grierson and his aide, Lieutenant Samuel L. Woodson.

The raid began in excellent conditions. The weather was fair and sunny as the brigade rode southeast to Pontotoc. The first day’s march covered nearly 30 miles, with the brigade camping that night at the Ellis Plantation, four miles northwest of Ripley, Mississippi. Little resistance or even enemy contact was experienced during this day. There was a brief skirmish with five or six Confederate soldiers in which three were captured. Another Mississippian, a civilian who was driving an ox team, had a hat “which one of the boys took a fancy to, and relieved him.” Colonel Prince, commanding the offending Seventh Illinois, compensated the robbed man by paying $2 in Union greenbacks.

At this point the Confederates were only just discovering that a raid had started. Additionally their attention was divided. Streight was already in northern Alabama along with a large infantry force commanded by General Grenville Dodge, while Smith was taking an infantry brigade – initially by railroad – down the Mississippi Central line towards the Tallahatchie River.

At 7:00 am the brigade mounted up and headed southeast. The weather was again excellent. As the on the first day, little enemy contact was made. The brigade passed through Ripley at 8:00 am, and crossed the Tallahatchie River at three places near New Albany. There they encountered light resistance. The Seventh Illinois sent one battalion to capture a bridge at New Albany. They encountered a few Confederate skirmishers there and drove them off. An advance company was sent forward to the bridge, where they found a picket attempting to destroy it. These men were driven off and the battalion crossed over the bridge. The rest of the Seventh as well as the Sixth Illinois crossed at a ford, two miles upstream at Arizabee, while the Second Iowa forded four miles west of that. The brigade reunited in New Albany, at 5:00 pm, then camped for the night at Sloan’s Plantation, five miles south of New Albany.

By the second day, the Confederates were starting to react to the raid. Chalmers was engaged with Smith’s column. Additionally, he became aware of a new Yankee probe – this one down the Mississippi and Tennessee Railroad. As a result only Ruggles’ First District troops were available to intercept Grierson; Chalmers was too busy. Ruggles sent Barteau’s cavalry scouting for Grierson’s men. A patrol of Barteau’s men were the troops that made contact with the Yanks north of New Albany, and picketed the bridge. Word of the Yankee presence soon worked its way to Barteau, but he was still uncertain as to the raid’s size or Grierson’s intentions.

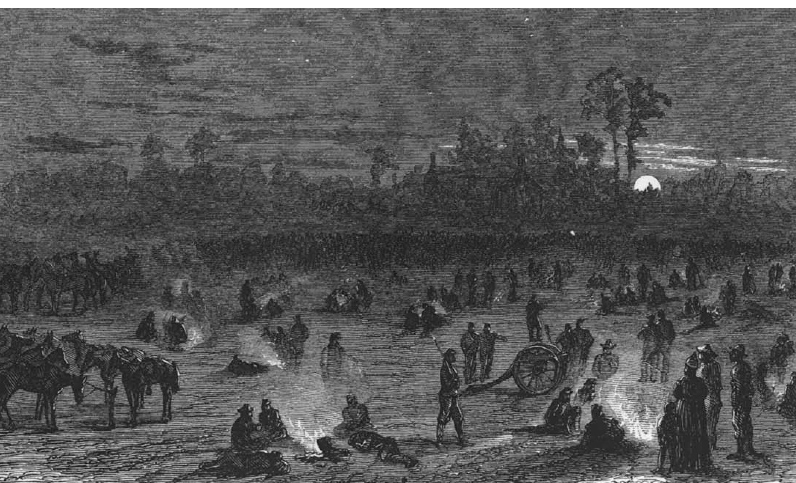

The fair weather with which the raid began had disappeared by April 19. Rain began bucketing down after sunset on April 18, and persisted throughout the night. It continued rainy for the next few days. This would work to Grierson’s advantage: the rain limited visibility. While it slowed Grierson, it slowed his opposition too. Grierson also knew where he was and where he was going, while they did not. Further, Grierson had some general idea where his opponents were.

To confuse pursuit, Grierson broke up his regiment at the start of April 19. He sent one detachment of the Seventh Illinois back to New Albany, the Second Iowa to Chesterville, Mississippi, to the southeast, and another northwestward to King’s Bridge. The object of these moves was to behave as if the purpose of the raid was to attack Confederate cavalry camps in northeast Mississippi. The King’s Bridge thrust came up empty, as the troops there belonged to Chalmers’ command and had left to deal with Smith. They brought word to Grierson that the Confederates had burned the Mississippi Central bridge at the Tallahatchie River. Grierson felt this news meant that railroad was cut close enough to Oxford to satisfy that portion of his orders. Thereafter his attention was focused south and east.

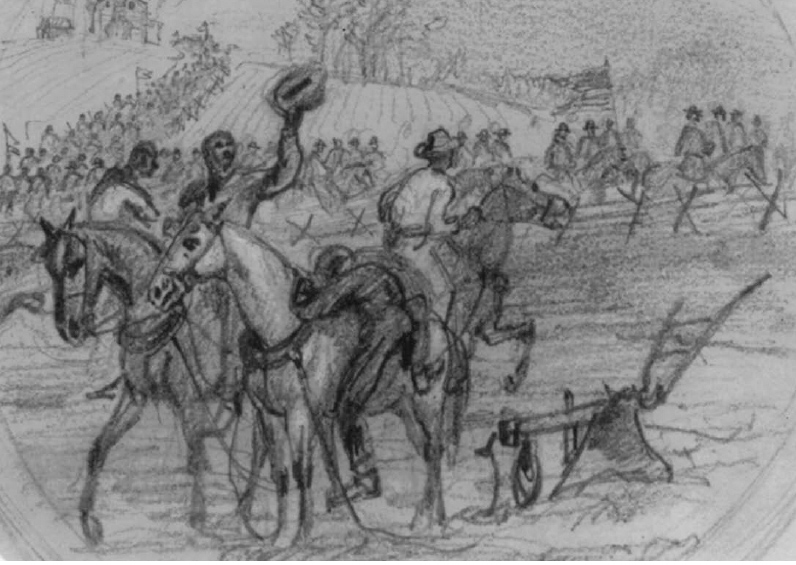

The Sixth and Seventh Illinois Cavalry in march order. This photograph was taken by a Confederate agent in Baton Rouge and shows Grierson’s brigade at the end of their raid. (AC)

At New Albany the Seventh Illinois flushed out 20 Confederates, and killed or wounded eight. After these morning feints the brigade converged at Pontotoc, which the Sixth Illinois reached first, at 4:00 pm. They met light resistance. One Confederate militiaman was shot and killed while sniping at the Union troops. Another squad of militia in Pontonac fled at the approach of the cavalry. They left behind a wagon, loaded with ammunition and camping equipment, which was destroyed.

The Seventh Illinois brought up the rear, as they had been seeking horses along the way. They failed to find horses, but when they stopped for dinner, some “foraging” troopers found a cache of weapons and gunpowder in one of the houses along the route. Against orders, the finders “accidentally” burned the house. Another detachment of the Seventh Illinois came across 500 bushels of salt owned by the Confederate government. This too was destroyed.

After riding through Pontotoc, the brigade camped at two plantations five miles south of Pontotoc – Weatherall’s and Daggett’s on the road to Houston. After they had camped, Grierson inspected his command. He selected 175 men who he felt were incapable of hard riding, as well as the worst horses. By this time the brigade had managed to capture a sufficient number of first-class remounts to replace the inadequate horses and mules. The unfit men and beasts were collected into a provisional battalion and placed under the command of Major Hiram Love of the Second Iowa. Grierson also assigned one of his six Woodruff guns to this unit – which the rest of the brigade dubbed “the Quinine Brigade.”

Grierson detached the Quinine Brigade from his command soon after midnight on April 20. They were ordered to return to La Grange, and give the impression that they contained the entire raiding force. This was Grierson’s first attempt to deceive the Confederates as to the intended depth of the raid. With luck, they would follow Love’s detachment, thinking it was Grierson’s brigade.

Love did his best to help the deception. He started north at 3:00 am, marching in columns of four to produce the illusion that he had a full regiment. The riders took all of the Confederate prisoners with them, and led spare horses and mules, further increasing the number of northbound hoof prints. They rode through Pontotoc to ensure that they would be spotted moving north. Love also had the lone Woodruff gun wheeled back and forth over the same ground to leave four sets of tracks.

Two hours later, at 5:00 am, Grierson led the rest of his brigade south, toward Houston, Mississippi. He reached Houston at 4:00 pm, but then he moved off the road, and traveled cross country around Houston. From there he pushed south another 12 miles toward Clear Springs, halting for the night at the plantation of Benjamin Kilgore. In all, the brigade had ridden over 40 miles in one day.

Grierson failed in his objective of convincing the Confederates that he was heading back north, however. His ride around Houston had been noticed, and locals had sent word to Colonel Clark Barteau, commanding Ruggles’ cavalry. At this point, Barteau’s cavalry was the only force that could catch Grierson, and he was riding hard in pursuit. The reports received exaggerated Grierson’s strength, so Barteau wanted to find and fix Grierson, holding him until more help arrived. There was help at hand, as Buford’s brigade of Loring’s division was in the process of being transferred to Tennessee. It was strung out along the Gulf and Ohio, where the regiments were halted to await developments.

On the third day of the raid, Grierson’s brigade camped at Weatherall’s plantation south of Pontotoc. This plantation was owned by the brother of the man who commanded Confederate state forces in the area. (MOA)

Grierson had a raider’s instincts, and decisions he made on the 21st proved it. He felt uneasy about the success of the deception attempted with the Quinine Brigade. He sensed rather than knew that he was still being closely pursued, and decided that a larger diversion was needed. Grierson decided to detach an entire regiment. Before leaving camp he had arranged for the Second Iowa to strike east towards the Gulf and Ohio.

Grierson chose the Second Iowa for this independent mission based on several factors. Its commander, Edward Hatch, was Grierson’s most senior regimental commander, as well as his most talented subordinate. The Second Iowa was his largest unit. It started the raid with 700 men, and still had over 500 even after the culling at New Albany. Finally, it was the only unit equipped with repeating rifles. It could maintain a heavier rate of fire, but would run out of ammunition faster. The detached regiment would return to La Grange sooner, which would allow the Second to use its rifles to best advantage.

Hatch was unhappy at the prospect of being sent off, and even less happy when, due to a mix-up in orders, the brigade broke camp and headed southeast at 6:00 am rather than the intended 3:00 am. Two hours later, when the brigade reached the road junction where roads led to West Point, Columbus, and Louisville, Hatch, the Second Iowa and one of the five remaining Woodruff guns took the road to Columbus. Grierson with the rest of the command followed the Louisville road.

Hatch had been ordered to strike the Gulf and Ohio, destroying the railroad from West Point to Macon, then to cut north, burn Columbus, and return to La Grange. These orders proved overly ambitious, but the tracks the Second Iowa made toward West Point decoyed Barteau and the rest of the Confederates away from Grierson.

Barteau and his cavalry had been chasing Grierson since April 18. On April 21 Barteau’s men were thundering southwest after Grierson and rode into Kilgore’s plantation around 10:00 am. His scouts moved south following Grierson’s tracks. It was still raining hard. At the road junction, they saw two sets of tracks – one heading south and one heading east. Grierson had taken the precaution of having one battalion of the Second accompany him south for a while before doubling back in columns of fours.

Barteau’s scouts saw the fresher tracks headed north and then east. Hatch had also run his Woodruff gun back and forth, leaving four sets of tracks. Barteau and his men assumed that all the Yankee raiders had doubled back then headed east. Barteau’s command went after Hatch and caught up with the Second Iowa at Palo Alto where it had halted for lunch, eight miles from the road junction, and about five miles northwest of West Point. Barteau ordered a charge.

Hatch deployed his men and gun. A short, sharp action ensued where the firepower of the repeating rifles stopped the charge. Then the lone Woodruff gun joined in. It was the first time many of the militia troops with Barteau had been under artillery fire. They scattered and ran. Hatch took this opportunity to remount his regiment and ride north to Okolona. Over the next two days Hatch’s men rode north with Barteau following and increasing numbers of Confederate troops joining the pursuit. But the Second Iowa outran them all, burning bridges as they crossed, slowing the chase. In going through northern Mississippi swamps, they ran across slaves sent into the swamps with their masters’ horses. Slaves and horses joined the Union cause, and by the time the Second Iowa safely reached La Grange its numbers had been swelled by 200 “contrabands” leading 600 spare horses.

Yet Hatch’s biggest accomplishment was to give Grierson an open road south. The Second Iowa’s repeating rifles convinced Ruggles that Barteau had caught a full cavalry brigade, not merely a regiment. While other Confederate units reported contacts with Grierson on April 21, these were initially dismissed as diversions. Grierson pushed south, keeping to the road for speed until he reached Starkville, at 4:00 pm. There Grierson captured Confederate government mail and supplies, reading the mails and destroying the supplies. He continued south from Starkville, cutting through swamps, riding belly-deep in mud and water for five miles. It was fully dark before they found an island high enough to encamp for the night. They had traveled 25 miles under wretched conditions, and the miserable weather precluded any real chance for sleep that night, but they were now poised to accomplish their main objective.

Colonel Edward Hatch commanded the Second Iowa during Grierson’s Raid. He was one of the outstanding Union cavalry generals of the Civil War, and invited to take a Regular Army commission afterwards. This picture shows him as a young brigadier general during the Civil War. (LOC)

Grierson’s predicament now was concealing his intentions while gaining information about his surroundings. He was deep within enemy territory, and completely on his own. That night he found a solution to these problems. The quartermaster sergeant of the Second Iowa, Richard Surby, volunteered to lead a squad of scouts. Surby proposed to Lieutenant Colonel Blackburn, the Seventh Illinois’ executive officer, that Surby be allowed to recruit a dozen men willing to dress in civilian clothing, armed with weapons captured from the enemy. These scouts could pass themselves off as Confederates, allowing them to gain valuable intelligence.

The plan was risky. Any scout captured while dressed in this manner could be executed as a spy. In 1862 eight participants in the Andrews Raid – an attempt to steal a Confederate locomotive – were hanged after being captured because they were wearing civilian clothing when they stole the train. Abel Streight had asked his superiors for permission to dress scouts as Southern civilians before starting his raid, and had been forbidden from doing so. But Grierson did not know of the orders given to Streight. Blackburn forwarded Surby’s suggestion and Grierson agreed to the plan.

Surby found eight volunteers, primarily among the Seventh Illinois. Their comrades held their carbines and uniforms and these scouts were soon ranging far outside Grierson’s lines. The two regiments got into the spirit of the game, dubbing the squad the “Butternut Guerrillas” after the butternutcolored clothing worn in the South and by the squad. Confederates were not the only risk faced by these men. Coordinating their efforts with Grierson’s pickets was critical, lest they get shot while attempting to return to friendly lines. Nevertheless, over the next week the Butternut Guerrillas gave Grierson a badly needed edge.

That night runaway slaves told Grierson about a Confederate leather factory near Starkville. Grierson dispatched a battalion of the Seventh Illinois, led by Major John Graham. They soon found the place, and captured it, along with a quartermaster officer from Port Hudson. The place was filled with boots, hats, saddles, and tack awaiting shipment to the Confederate army at Vicksburg. Graham had the buildings torched.

The battalion was back at the camp before dawn, and at sunrise the two regiments saddled up and continued to Louisville. The ride was through Noxubee River bottomlands, a maze of thickly wooded swamp. Much of the 28-mile trip was made through mud and mire belly-deep for a horse. The artillery was broken down and packed across on horseback.

Before reaching Louisville, Grierson sent off two more diversions. He sent Captain Henry Forbes of the Seventh Illinois with his command, Company B, to Macon, Mississippi. Forbes was told to break the Gulf and Ohio railroad, cut the telegraph line at Macon, and then rejoin the column. He had only 32 men with which to accomplish this, but set forth with a will. Shortly after the company left, Grierson dispatched two more volunteers – Captain John Lynch and Corporal Jonathan Ballard of the Sixth Illinois – to cut the telegraph line that paralleled the railroad. These men rode in civilian disguise. He also sent a battalion of the Sixth Illinois ahead to Louisville, to take the town and keep inhabitants from leaving with word of Grierson’s approach.

By this time Grierson was well ahead of news of his approach. Once the column was clear of the swamp, local civilians who spotted the force assumed it was Confederate. At one point, students at a school were turned out to cheer as “Van Dorn’s cavalry” passed. At another spot Grierson requisitioned food from a mill. The owner grumbled about the slowness of receiving payment from the Confederate government, and told the Yanks that they should be chasing down Grierson instead of robbing him. The Yankees took care not to spoil the illusion. Shortly before reaching Louisville, they captured a Port Hudson-bound mail coach carrying government money and letters. Both were confiscated.

It was dusk by the time the column reached Louisville, but they pushed through the town without halting. Ten miles beyond the town Grierson found some high, dry ground at the Estes Plantation, and finally halted for the night. In all, the raiders had pushed over 50 miles deeper into Confederate territory that day. They were now only 40 miles from their objective – the Southern Railroad.

By now Pemberton knew there was a deep raid into his district, but did not know its objective. On one level, he knew that a raid in eastern Mississippi was an attempt to draw troops away from the Mississippi River. He would not fall into that trap – the garrisons at Grand Gulf and Vicksburg remained unchanged. However, he was forced to commit reserve troops – mainly those from Loring’s division. Pemberton’s assumption was that the Gulf and Ohio was its objective. He sent orders to Buford’s brigade, dispersing the regiments along that rail line. He also sent General Loring from Camp Pemberton to Meridian, to coordinate activities in chasing down the Yankee cavalry. Pemberton’s order cleared the Southern Railroad of Confederate troops from Jackson to Meridian.

Grierson’s men broke camp at daybreak, and continued south. The Woodruff guns were remounted. The carriage of one gun had broken, so it was mounted on buggy wheels, taken from the plantation. Grierson was nearing the Pearl River, the last terrain barrier before his objective. It was too deep to ford. To capture a bridge before it could be destroyed, Surby and his scouts were sent ahead. There they found five civilians armed with shotguns preparing the bridge for destruction. Through a combination of bluff and threats, Surby convinced the men to run or surrender without fighting. Surby’s men replaced the removed planks, allowing the bridge to be used.

William Surby and his “Butternut Guerrillas” were able to save the bridge over the Pearl River north of Philadelphia, Mississippi, through a combination of bluff and speed. Its capture enabled Grierson’s men to reach Newton ahead of news of their arrival. (MOA)

The men demolishing the bridge were from Philadelphia, Mississippi, the brigade’s next destination. The ones who escaped rode home, warning of the approaching column. Locals began sniping at the approaching scouts, and when Surby reached Philadelphia he found a crowd of armed militia blocking the road. Surby rode back to the advanced guard, and got ten troopers. With these men and his squad, he returned to Philadelphia, and charged into the armed mob. The militiamen scattered, and the Yanks captured six prisoners and nine horses. Among the prisoners was the county judge, who had organized the resistance.

By the time this brief battle was over, the rest of the brigade had reached and surrounded Philadelphia, preventing anyone from leaving. Grierson rode into town to sort things out. He was informed by the judge that he had gathered an armed party to keep the town from being looted and burned. Grierson gave an impromptu speech in the town square, stating that his men had strict orders to destroy only Confederate government property. No further resistance was offered, and Grierson’s men finally rode out of Philadelphia at 3:00 pm, Grierson leaving a rear guard, commanded by Colonel Prince, to keep word of the Union presence from spreading. Prince lined up the town’s inhabitants and had them swear to keep silent for the rest of the day.

As they were leaving for Decatur the column was overtaken by Lynch and Ballard, who reported that they had failed in their attempt to cut the telegraph line. The two had reached Macon at 8:00 am that day, where they were stopped by the picket. The two Yankees spun a tale about being part of a militia unit at Enterprise, Mississippi, which had been visited by Yankee cavalry the day before. They explained to the picket that they had been sent to Macon with word of the raider. The two learned that Macon was occupied by three Confederate regiments including reinforcements from Mobile, Alabama.

Realizing they had no chance of cutting the telegraph, Lynch made an excuse to allow him to leave. Once out of sight, they rode hell for leather to catch up with their old command. Their most valuable contribution was to refocus attention on the Gulf and Ohio. Confederate reinforcements were sent to Enterprise instead of where they could have been useful.

Forbes and his company had likewise approached Macon on the previous evening. These men had looped north around the town and, doing some careful scouting, they captured a few straggling Confederates. Forbes similarly learned that Macon was too well garrisoned for a company – or even the whole brigade – to raid. They camped the night at a plantation three miles from Macon and on April 23 they gave up Macon as a bad job, and began riding back, seeking Grierson. En route they captured a Confederate soldier, and pressed him into service as a guide. The company was north of the Noxubee, which was unfordable, near Macon. They tried to ride over a bridge they had used previously, only to find that it was now guarded by a force too strong for a cavalry company to challenge. So they had to go upstream to find a place to cross. The delay left them more than a day behind Grierson.

Meanwhile, Grierson and the main body were pressing south. They camped at a plantation five to seven miles south of Philadelphia, but they rested there only until 10:00 pm. They were a long day’s ride from the Southern Railroad but Grierson, with his innate feel for timing, felt the need to press on. He sensed that the road ahead of him was open, and that while Newton was unguarded, it might not remain so for long.

Railroad track was destroyed by burning the ties with the rail on top. Once the middle of a rail was red hot, soldiers could take the ends, twist the rail, and then bend it around a tree or pole. (LOC)

Grierson was right: Forbes and his company had been spotted near Macon. Lynch had reported Union troops at Enterprise, and reports that Pemberton was receiving multiplied the size of the Union raid. The speed with which Grierson moved increased the confusion. Graham’s raid on the leatherworks near Starkville occurred on April 22, but was not reported to Pemberton until April 25. This was leading Pemberton and his subordinates to cast about for Grierson well north of his actual position. Although reports were coming in from all over, the greatest number of sightings was being reported close to the Gulf and Ohio. Pemberton’s attention was focused at the wrong point.

After a short stop south of Philadelphia, Grierson was again on the march. The brief rest refreshed his men, and they rode through the rest of the night. Grierson sent an advance force ahead – two battalions of the Seventh Illinois, led by Lieutenant Colonel Blackburn. They were supposed to secure Decatur, Mississippi, the final town before Newton, and then scout Newton ahead of the rest of the brigade.

Blackburn, in turn, sent out Surby and his scouts to reconnoiter, who were again mistaken for Van Dorn’s cavalry by the locals. Surby learned that the only Confederate troops in Newton were 150 convalescents in an army hospital there, but that large numbers of troops had moved through Newton heading east in the past few days.

Blackburn passed Decatur before sunrise, and then pressed on to Newton. He halted outside around 7:00 am, and sent Surby with two scouts to learn the situation. Surby wandered around the town, learning that there was a westbound freight train approaching Newton and that there was also a passenger train due at 9:00 am. By then it was around 8:00 am. Surby sent one scout back to Blackburn with news of the approaching trains.

Blackburn and his men rode in and took the town, capturing the hospital, before the freight train arrived. Pickets were sent to secure the town exits, while other men hid by the switches to the siding, and the rest of the troopers concealed themselves from the railroad. All this took place without a shot. The train – 25 cars long – puffed into the station and found itself trapped, shunted on to a siding. After taking the crew off, the Yankee cavalrymen hid. The eastbound train – a mixed passenger and freight – was also surprised and captured.

Blackburn and the Seventh Illinois set to work destroying both trains. The freight train was filled with ordinance and commissary stores bound for Vicksburg, as well as timbers and planking to repair railroad trestles. The eastbound train contained one passenger car of civilians fleeing Vicksburg. Two of the freight cars contained their goods. Of the rest, four contained ammunition and six commissary stores. The passengers’ possessions were not military contraband, but the cars were. The troopers unloaded both baggage and furniture off the boxcars, the train’s cars were moved to the sidetrack with the freight, and all of the cars torched.

There was a critical shortage of locomotives in the Confederacy. Most were the 4-4-0 “American” configuration, with four guide wheels and four drive wheels, like this destroyed Southern locomotive. (LOC)

By the time Grierson and the main body were in earshot, the ammunition in the burning boxcars had started exploding. Thinking the noise was the sound of battle, the main body came in a rush, to aid their comrades. When Grierson arrived, he was both annoyed at the scare and relieved there were no Confederate combatants in town, and set the brigade to work in earnest.

Grierson was aware that there were a lot of Confederates on the Gulf and Mobile. He dispatched two battalions of the Sixth Illinois under Major Starr with instructions to destroy bridges, trestles, and telegraph lines east of Newton. He sent Captain Hening and the third battalion of the Seventh Illinois west with similar instructions.

In Newton, the brigade had taken 75 prisoners from the hospital. These men were released on parole – they signed a statement pledging to take no further part in the war until properly exchanged for Union prisoners. This proved extremely popular as it effectively gave these men home leave until exchanged. A Confederate warehouse filled with clothing, weapons, coffee, and sugar had been found and was burned. But Grierson allowed the paroled prisoners to join his men in removing such of the clothing (which were captured Union uniforms) and consumables as they could use and carry off before burning the building.

In addition to the warehouse, the railroad depot and facilities were burned, telegraph equipment removed or destroyed, and the two locomotives exploded. Railroad ties were burned, and the fires used to heat the rails so that they could be bent and twisted. As previously, civilian buildings were spared. Soldiers even joined in with townspeople to douse fires in houses accidentally started by exploding ammunition.

By 2:00 pm the work of destruction was complete. Major Matthew Starr, of the Sixth Illinois, returned with a report that three bridges and several hundred feet of trestle and track had been destroyed over an eight-mile stretch east of Newton, along with telegraph lines and poles. This included the bridge over the Chunky River. Hening’s force had similarly torn down telegraph lines and burned a bridge half a mile west of Newton. The brigade mounted up and headed south.

Having achieved his primary mission, Grierson’s objective was now survival and escape. Since Grierson knew Confederate forces were seeking him north of Newton, he decided that safety lay to the South. To outrun pursuit and allow his men to recuperate he wanted to press on for another 15 to 20 miles.

At first their ride was slowed by refugees fleeing Newton. Once they learned that Grierson’s brigade was leaving civilians and their property alone – Grierson even provided escorts back to Newton for those who wished to return – the flood became a trickle, opening the road. The citizens of Garlandville, two miles south of Newton, attempted to stop the raiders, turning out a militia primarily consisting of superannuated warriors armed with shotguns. A cavalry charge scattered them. Grierson confiscated their weapons and released them. One militiaman offered to serve as a guide, revealing pro-Union sentiments once out of town. The brigade rode another 12 miles before camping for the night at the Bender Plantation, two miles west of Montrose, Mississippi.

In the meantime Forbes and his company rode south in pursuit of Grierson. By noon they had reached Philadelphia only to learn that Grierson was long gone. They pressed south, but their progress was slowed by snipers and guerrillas – the country had been stirred up by Grierson’s passage. By nightfall they passed through Decatur, and camped two miles south of that town. The next day, they told themselves, they would catch up with Grierson at Newton.

The Confederates were also searching for Grierson but looking in the wrong place, still focused on defending the Gulf and Ohio Railroad. April 24 passed with a frustrating lack of intelligence. The only clue that something had happened was a negative one – a lack of telegraph traffic through Newton. Messengers from Newton were carrying word, but they were riding exhausted horses left behind by Grierson, who confiscated all good horses he found as remounts.

April 25 was a Saturday, but Grierson intended it as a day of rest. He allowed his men, who had had four hours’ sleep between the dawn of April 23 and sunset on April 24, to sleep until sunrise. The next few hours were spent tending to gear and horses, eating a leisurely meal (unwillingly provided by their host), and planning. They did recompense the plantation’s owner by providing a receipt for goods confiscated. Of course, the receipt was worthless until the Yankees occupied that part of Mississippi.

APRIL 25, 1863

Captain Henry Forbes brought Company B of the Seventh Illinois to Enterprise in search of Grierson's brigade, which he had been told was heading there. Unfortunately, this was disinformation planted by Grierson to confuse any pursuers. Instead, Forbes found a Confederate infantry regiment entrenched in the town, with a second regiment unloading by rail car. Rather than surrender or fight against suicidal odds, Forbes called for a parley and demanded the surrender of Enterprise in the name of Benjamin Grierson. While the garrison discussed the possibility of surrender, Forbes and his men took the opportunity to escape to the west.

UNION FORCES

1 Company B, Seventh Illinois, commanded by Captain Stephen Forbes

2 Captain Henry Forbes and Union delegation

CONFEDERATE FORCES

1 35th Alabama Infantry, commanded by Colonel Edwin Goodwin

2 Confederate infantry regiment arriving by train

3 Colonel Edwin Goodwin and Confederate delegation

Grierson knew that the Gulf and Ohio was heavily garrisoned. Although he had left hints that he was headed that way to occupants of the towns through which he had passed, he had no intention of heading east. He also felt that it would be unwise to retrace his path. He planned to ride east for a day or two, and collect reports from his scouts. He then planned to cut north, crossing the Southern between Jackson and Lake, and then ride through central Mississippi. Alternatively, Grant was due to land at Grand Gulf. If the way north was blocked, Grierson could continue east and link up with Grant.

Regardless, the horses were in poor shape after all the hard riding. Grierson confiscated the stock he found at Bender’s Plantation. He also planned an easy ride west. Accompanied by two slaves – the first of many that Grierson would accumulate over the last half of his travels – the brigade started off at 8:00 am.

They traveled only five miles before resting at another plantation, where the only occupants were five women, at least one of whom was pro-Union. While most of the brigade rested until 2:00 pm, Grierson dispatched parties to find horses hidden in the swamps, woods, or byroads. Afterwards they continued their westward progress, finally stopping when night fell at the Mackadora Plantation 17 miles west of their starting point.

From there Grierson began another diversion. He chose Sam Nelson, one of Surby’s Butternut Guerrillas, for a single-handed raid on the telegraph line that paralleled the Southern Railroad. If possible, Nelson was to fire a bridge or trestle. The man left at midnight.

Meanwhile, Forbes’ company continued their pursuit of their brigade. They galloped to Newton, where they found that Grierson had been and gone. Grierson’s generosity towards civilians and combatants paid dividends at this point, because the townspeople and paroled prisoners gave the Yankees a cordial greeting, politely answering Forbes’ questions. Forbes learned of the fight at Garlandville, and that Grierson had indicated he was heading east toward the Gulf, and Mobile afterwards. There were also rumors of Yankees at Enterprise, Mississippi, garbled retellings of the sighting of Forbes and his men at Macon.

So off the company went to Enterprise, and through hard riding arrived a little after 1:00 pm. The intelligence they gathered en route indicated that there were no Confederate troops there, so they rode within sight of the town. To their dismay they saw a regiment of Confederate infantry in Enterprise, and another regiment unloading from a newly arrived train. It was too large a force to fight, and they were too close to escape. Surrender was undesirable.

Forbes decided upon a bold course. He approached the town with a small party under a flag of truce. While panicky Confederate sentries fired shots at the approaching men, Forbes persisted, riding up to a barricade, and demanding to speak to the commanding officer. He was met by Colonel Edwin Goodwin, commanding the 35th Alabama Infantry, garrisoning Enterprise.

Forbes then demanded the surrender of the garrison. He informed Goodwin that Brigadier General Benjamin Grierson (giving Grierson an unofficial promotion) had a brigade of cavalry poised to attack the town, but wished to offer an opportunity to surrender to spare bloodshed. Goodwin asked for an hour in which to consider a response, and Forbes replied that he had the authority to grant the request. The parley ended with Forbes stating that he would be back in an hour for the answer, and both groups departed.

The Confederates spent the hour further fortifying their position – sending to Macon for further reinforcements, forwarding the note given to them by Forbes. Forbes and his men used the time to flee to the west. No second parley was held. Once safely away, the company decided to continue after Grierson, so they retraced their path, reaching Garlandville by dusk. There Forbes found that the Garlandville militia had reconstituted itself into a 60-man force of “Garlandville Avengers.” One of Forbes’ scouts, in butternut disguise, convinced the Avengers’ picket that Forbes’ men were Alabama cavalry seeking Grierson. The Yankees passed through the town unmolested. The Garlandville men even provided the scouts with information on Grierson’s previous appearances and probable destination. They rode west until well past midnight, stopping at Hodge’s Plantation for a few hours’ sleep.

For the Confederate command, April 25 was the day the thunderbolt fell. Word finally reached both Pemberton in Vicksburg and Loring in Meridian of the previous day’s destruction of Newton Station. Other reports trickled in to Pemberton throughout the day – word that a leatherworks at Starkville had been burned, and that Yankee cavalry brigades had been seen at Enterprise and Macon. As a result, Pemberton’s focus changed from Grant’s movements on the river to Grierson’s raid. No one had dreamed that the Yankees would penetrate to the Southern Railroad, and Pemberton suddenly realized how vulnerable Vicksburg would be if that supply line were permanently cut.

Grierson’s extraordinary mobility was achieved through a willingness to travel through seemingly impassible terrain. More than once his column rode for hours with the horses belly-deep in water and mud. (AC)

A flurry of orders went out. Pemberton sent General Adams and his force from Jackson to Lake, just west of Newton. He ordered troops from Fort Pemberton to cover the Southern from Morton, Mississippi, to Jackson. He sent artillery to the Big Black Bridge to cover the railroad crossing there. He ordered the cavalry under Wirt Adams to search for Grierson. He also sent messages to the Grand Gulf and Port Hudson garrisons to be on the lookout for the Yankee cavalry, and to send what cavalry they had in search of the raiders.

Word was passed to Ruggles that Barteau and his cavalry had been deceived by a decoy force. The exhausted Confederate cavalry again cast south, determined to keep Grierson from escaping once more if he came north. Loring moved his forces up and down the Gulf and Ohio, and west along the Southern Railroad to the Chunky River. Grierson’s men had successfully hit Newton, but the Confederates wanted to extract a price for that success.

Grierson’s day started early. Nelson returned before dawn with an alarming report: he had not reached the Southern, having been stopped by Confederate cavalry. Nelson had convinced their commander that he was a paroled Confederate. He also decoyed the Confederates by reporting that Grierson had been in Garlandville with 1,800 men the previous day at noon, and that they were heading east toward the Gulf and Ohio. Nelson hurried back to Grierson after giving the Confederates directions to Garlandville. The cavalry force was large enough to challenge Grierson, and they would soon find the tracks left by the Yankees the previous day.

The ferry over the Pearl River was captured when the ferryman mistook a Union scout for a Confederate cavalryman. Capture of the ferry intact allowed the brigade to cross the Pearl River 24 men and horses at a time. (MOA)

Other scouts reported that all of the Southern Railroad stations between Jackson and Lake were garrisoned, and that Grant was soon expected to attempt a landing at Grand Gulf. Breaking camp at 6:00 am, Grierson decided to push west and link up with Grant. They passed around Pineville, across the Leaf River, through Raleigh, and on through Westville after dark. Along the way they were joined by a number of slaves – free and runaway – who delighted in showing the Yankees where “master” was hiding his food and horses. The cavalrymen burned the bridge at Leaf River to slow pursuit, and captured the sheriff of Smith County at Raleigh, relieving him of $3,000 in Confederate government money. They spent the night at the Williams Plantation two miles west of Westville. The owner, in residence, was a Confederate officer on leave. He was captured and paroled.

Forbes and his party resumed their pursuit of Grierson. They too pushed west shortly after dawn, and were soon on the track of their brigade. Unfortunately, they were slowed when they reached each stream or river by the bridges burned by their comrades. They took time to cast for fords, swimming their horses across at some points. Then, at Raleigh as at Garlandville, they discovered a militia had formed to protect the town. This time B Company dispensed with trickery. Charging the militiamen, B Company scattered them, winning through the town.

Forbes asked for three volunteers to press on ahead of the company. His brother, Sergeant Stephen Forbes, and two privates stripped their horses of all unessential equipment – including their carbines and sabers – and pushed them down the road as fast as possible. The three would ride all night, followed by the rest of the company.

Forbes’ company was lucky to have avoided the cavalry Nelson had encountered. These troops had hared off to Garlandville, and so were out of the chase. Pemberton was receiving a flurry of reports of Union cavalrymen throughout Mississippi, and phantom Yankees were again spotted near Enterprise. There was even a report of 1,000 Northern cavalry at Kosciusko, well north of the Southern Railroad, but threatening the Mississippi Central line. The most accurate report came from General John Adams, who stated that Grierson and 800 Yankee cavalry were 15 miles south of Lake, and would probably attack either Forrest or Lake. But this report was ignored.

Instead, Pemberton sent a brigade to cover the Mississippi Central line, and focused attention on the Gulf and Ohio. Pemberton also directed Wirt Adams and his cavalry to cover Claiborne and Jefferson Counties, to catch Grierson if Grierson was headed to the Mississippi. He also sent an urgent telegram to his superior, General Joseph Johnston, requesting the immediate return of Van Dorn’s cavalry. Unfortunately, these men were either raiding northern Tennessee or chasing Abel Streight through Alabama and Georgia.

Grierson made an early start Monday morning, sending Prince and two battalions of the Seventh Illinois off well before daybreak. They were to push on to the Pearl River, and secure a ferry across the river. Grierson had learned of the ferry from the captured sheriff – it offered one of the few ways across the Pearl, which was too deep to ford and too wide to swim south of Jackson.

Prince reached the ferry before dawn through hard marching, and captured it intact, when the ferryman brought it to the east bank, thinking that the Seventh Illinois were Confederate cavalry. Prince immediately sent a party across to hold the far bank, and waited for the rest of the brigade. Grierson started the rest of his force two hours after Prince, and was close behind. They were crossing the Strong River and making preparations to burn the bridge when Sergeant Forbes and his party came riding up, reporting that the rest of Forbes’ company was behind them. Grierson strengthened the party at the bridge to serve as a rear guard, to hold it until Forbes’ Company B rejoined the brigade. Once Captain Forbes and his company crossed the bridge, Sergeant Forbes set fire to it.

Meanwhile, at the Pearl River the brigade was slowly crossing, 24 horses at a time. Prince sent two scouts, dressed in butternut, ahead to Hazelhurst, the next town, and a depot for the New Orleans, Jackson and Great Northern Railroad (NOJ&GN). The two scouts boldly rode into town with a message to be telegraphed to Pemberton. It reported the ferry had been destroyed and the Yankees were trapped east of the Pearl River. They cut the telegraph after leaving the town, preventing any amendment of that report.

The NOJ&GN was part of the main supply line for Grand Gulf. While neither Hazelhurst nor the NOJ&GN were part of the original plan for the raid, Grierson was in a position to attack it as he had hammered Newton. Grierson and Prince were not going to let that opportunity slip. Prince swept in with the advance guard in the late morning, capturing a string of boxcars loaded with munitions – mainly heavy shells. As at Newton, they heard that a second train was due, so they prepared an ambush. Unfortunately for the Yankees, the engineer sensed something wrong as he approached the station. Abruptly he stopped the train and threw the engine into reverse, backing out of danger faster than the cavalrymen could pursue.

A thunderstorm that had been threatening then opened up; Hazelhurst was experiencing a torrential downpour. This slowed, but did not stop, the destruction of track, both ties and rails. The town was searched, but no weapons were discovered in private homes. A cache of food for the Confederate army was found, and taken to a hotel to be cooked up for the brigade. Prince pushed the boxcars down the tracks, and burned those. Unfortunately, the filled shells exploded with enough force to set several homes on fire, despite the rain. As at Newton, Grierson and the main body heard the explosions and came at a charge, assuming that Prince’s force was being attacked. Instead the only enemy they found was fire, which they helped the townspeople to fight.

At 6:00 pm the brigade mounted up and headed west to Gallatin, and southwest afterward. Shortly after passing Gallatin they stumbled on a Confederate 64-pound Parrott, which was being pulled to Grand Gulf. The carriage and ammunition wagons were burned, and the gun spiked. Throughout, it was raining heavily. Grierson and his men finally camped for the night, four miles southwest of Gallatin at Thompson’s Plantation.

Grierson’s Raid inspired hundreds of black slaves to run away and seek freedom with the Yankee forces. Nearly 1,200 former slaves crossed into Union lines with either Grierson’s or Hatch’s columns. (LOC)

For Pemberton, April 27 must have seemed like the continuation of a waking nightmare. In the morning he received reports of Yankees near the Pearl River. Pemberton sent a warning to Bowen at Grand Gulf that Grierson might be headed his way and to be alert. Orders were sent to destroy the ferry over the Pearl River, orders apparently carried out, based on telegraphic reports from Hazelhurst that arrived with a promptness that would have been admirable had it not been the message Sergeant Surby had hoaxed the telegraph into sending. Soon afterward Pemberton received a telegraph from Crystal Springs – where the train that escaped at Hazelhurst had gone – that Hazelhurst was in Union hands. Alarmed, Pemberton ordered reinforcements to Big Black Bridge. If that were burned, Vicksburg would be untenable. He also ordered Barteau’s cavalry from northeast Mississippi to Hazelhurst, and ordered Gardner at Port Hudson to intercept Grierson.

Gardner responded by sending the Ninth Tennessee Cavalry to Clinton and Woodville. One company went up the NOJ&GN line to Jackson, and then Clinton, while the rest of the regiment hurried to Woodville, to head to Clinton from there. Both groups were following a path east of Grierson’s location and intended direction.

APRIL 27, 1863

At Hazelhurst, Lieutenant Colonel Blackburn hoped to repeat his successful ambush of an arriving train. However, the troopers of the Seventh Illinois were careless, and the train's engineer was more alert than at Newton. Sensing a trap, the engineer stopped his train, then reversed it, driving north to safety before the Union cavalrymen could catch it. Grierson and his men had to settle for destroying the rolling stock actually in the town and depot. Unfortunately, they underestimated the ferocity of the burning ammunition in the parked boxcars. The explosion set fire to several homes, and Grierson's men joined forces with the townspeople to put them out.

UNION FORCES

| 1 | Union cavalrymen posted around the town to prevent word of the town’s capture reaching Confederate forces |

| 2 | Union cavalrymen attempting to capture the Confederate train |

CONFEDERATE FORCES

1 Confederate train

EVENTS

EVENTS

1 Rolling stock burning

2 Buildings set on fire by the burning ammunition.

3 Grierson accepting the paroles of captured Confederate soldiers

Pemberton received one good piece of news that day. Loring reported that there were no Union cavalry near Enterprise, and that the previous reports exaggerated the size of Yankee forces threatening the Gulf and Ohio. Loring also suggested that Grierson was probably heading toward Baton Rouge – an appraisal that would have been useful days earlier, but was now too old to be worthwhile.

Grierson’s raiders made an early start on April 28, hitting the road at 6:00 am. Grierson knew that he was far too close to large Confederate troop concentrations for comfort, and was determined to push on and join Grant at Grand Gulf. After traveling a little way west, Grierson launched yet another diversion. This time he sent a battalion of the Seventh Illinois – Companies A, H, F, and M – under the command of Captain George W. Trafton to strike the New Orleans railroad south of Hazlehurst, at Byhalia. The rest of the command rode west, toward Union Church.

When stopped for lunch at Snyder’s Plantation, two miles northwest of town, the pickets were fired upon by a group of mounted men. These proved to be advanced elements of Wirt Adams’ cavalry, searching for Grierson. The exchange grew into a running skirmish, as the Yankees counterattacked and then pushed the Confederate cavalry back through Union Church. The Yanks held the town and bivouacked the night there.

Meanwhile, Trafton and his force reached Byhalia, and found it undefended. There was a Confederate camp there, but Trafton arrived while the troops were out hunting Yankees. Instead, the Yanks destroyed the camp and a burned a store of coal there. They then swept into Byhalia, destroyed the depot building, commissary stores, the water tower, a long railroad trestle near the depot, and a stationary steam engine that powered a water pump and sawmill. They also captured a Confederate quartermaster corps major.

On the way back to Grierson – who told them to rendezvous at Union Church – the scouts learned of the presence of Wirt Adams’ cavalry in the area, including a rough estimate of their strength – about 500 troopers and six artillery pieces. Better still they learned that Wirt Adams had set up an ambush on the trail between Union Church and Fayette, Mississippi – the route that Grierson had planned to take the next day. They told Grierson of the planned ambush when they arrived at the brigade’s bivouac at 3:00 am on April 29.

On April 28 Pemberton was redoubling his efforts to trap Grierson. He moved troops to Hazelhurst and Brookhaven to protect the New Orleans Railroad, and sent both an infantry and a cavalry regiment to Woodville to cut off any attempt to double back. Reports drifting in indicated that Grierson was going west, not south, so Pemberton sent a wire to Adams, advising the colonel that Grierson might be headed his way. Adams sent a patrol of 100 men to Union Church to scout. They soon made contact, but realized they were badly outnumbered. Their commander, Stephen Cleaveland, sent word to Adams, who moved to Union Church. While Adams had artillery, his force was outnumbered two to one. Adams decided he could not attack Grierson, so he set up the ambush on the road to Fayette.

Pemberton also cautioned Bowen at Grand Gulf to watch out for Grierson. Bowen had bigger worries than Grierson, however; he saw that Grant was loading troops up at Hard Times, Louisiana, for Grant’s push across the river.

When Trafton arrived with word of Adams at 3:00 am, Grierson was woken and given the news. From intelligence gathered through his scouts and provided by local blacks, eager to help the Yankees, Grierson learned that he had arrived at the vicinity of Grand Gulf too soon. Grant had not yet landed. Grierson was also aware that waiting for Grant would be suicidal. Forting up would only allow Pemberton to concentrate on Grierson.

Grierson decided to head for Baton Rouge, but also decided to convince his opposition that he was going in a different direction. The twenty-one prisoners taken the previous day were paroled, after hearing Grierson and his officers discuss the best way to Grand Gulf and Natchez. To cap this, Grierson allowed a civilian prisoner to overhear plans to ride to Natchez, and then allowed this man to “escape,” unparoled.

Wirt Adams led the Confederate cavalry that remained in western Mississippi after Van Dorn and most of the rest of Pemberton’s cavalry were transferred to Tennessee. Adams almost caught Grierson, to be foiled by Grierson’s unrelenting pace. (AC)

Grierson then had a battalion of the Sixth Illinois create a diversion to the west, while the rest of the brigade slipped off to the east. The Sixth Illinois troops soon rejoined them after driving the screening Confederates back toward Wirt Adams’ ambush. While the Confederates hid, waiting silently for the Yanks to spring the trap, Grierson’s men plunged into thickets east of Union Church. Over the next few hours, in Sergeant Surby’s words, “I do not think we missed traveling towards any point on the compass. The dodging succeeded in its goal of losing Adams. Adams did not discover that Grierson was elsewhere until 2:00 pm when a patrol sent to Union Church discovered it was deserted.”

By then Grierson’s men were approaching Brookhaven. Shortly after reaching the main road to the town they overran an ox and mule train carrying sugar. What sugar was not appropriated by Union troopers was destroyed. A scout of Brookhaven revealed several hundred Confederates in the town. Many did not have uniforms and few had arms ready, so Grierson felt that they would scatter if pressed. His assessment proved correct. The Confederate force, a mixture of recruits and militia, offered little resistance when the Seventh Illinois swept into town and over 200 were taken captive. Unwilling to carry so many prisoners, Grierson paroled them. Writing out the paroles took the adjutants the rest of the day – a process that lengthened as word went out that prisoners were being paroled. Many of the Confederates who had escaped returned to surrender, so that they too could sit out the war until exchanged. The rest of the brigade spent their time destroying the depot and railroad tracks. The Yanks made further friends by paying for all meals – with captured Confederate money. Finally they rode out of town, heading south for eight miles before stopping for the night well after dark.

Wirt Adams was not the only Confederate commander questing after Grierson’s men that day. The previous day Pemberton had mounted the Twentieth Mississippi Infantry, then at Jackson, with the intention of having them pursue the raiders. He handed command of this force to Colonel Robert Richardson and gave Richardson orders to get Grierson. Unfortunately, Richardson could not get the force under way until the morning of April 29, assembling the force at the depot at 2:30 am. Departure was further delayed because the locomotive proved incapable of pulling the assembled cars, nor was there wood to fuel the engine. It was not until daybreak – after uncoupling several cars and crowding troops and horses in the remaining ones – that the train puffed out of Jackson.

It arrived at Hazelhurst around lunchtime. There townspeople claimed that Grierson was returning, so the unit scouted the immediate area for nonexistent Yankees. Finally reports drifted in that Grierson was in Union Church, so the mounted infantry went off that way. When they arrived at 9:00 pm they learned from some of Adam’s men that Grierson had departed half a day earlier. Richardson rested two hours, and then headed back to Hazelhurst.

When Grierson and his men started riding early on the morning of April 30, much was happening elsewhere that would affect his raid. Four groups of Confederate troops were converging on Grierson – Wirt Adams riding down to Osyka from Union Church, Richardson and his men following the railroad south from Hazelhurst, and the Ninth Tennessee Cavalry scouting southwest from Woodville. More ominously, Gardner at Port Hudson dispatched Miles’ Legion – 2,400 troops including 300 cavalry and a number of guns – to cut off Grierson from Baton Rouge. Most were being sent to guard the crossings of the Amite River, which Grierson had to pass to reach Baton Rouge. Another force was sent to Osyka, to guard the supplies cached there.

Yet Grierson had not been forgotten by the Union Army. Sooy Smith finally learned from a spy that Grierson had struck Newton on April 24, and that Grierson was headed back north, through central Mississippi. The news was old and inaccurate, but Smith could not know that. To assist Grierson, Smith launched a number of raids into northern Mississippi. This included one commanded by Colonel Hatch, who had been given a threeregiment cavalry brigade that included his Second Iowa. Down the Mississippi, Grant, stymied at Grand Gulf the day before, shifted south and crossed the Mississippi River at Bruinsburg. He was marching on Port Gibson, which he would take the next day. Grant would learn of Grierson’s activities when he read a Confederate newspaper in Port Gibson. It was the first indication Grant had of Grierson’s presence since Hatch parted company with Grierson. Grant’s movement absorbed the attentions of both Bowen at Grand Gulf and Pemberton. Pemberton was too busy fighting Grant to further manage the pursuit, or to send additional troops after Grierson.

At Summit, the Sixth and Seventh Illinois tore up track, and burned the depot, water tower, and 25 railroad cars. (MOA)

Grierson and his men plunged south without knowledge of any of this, however. On April 30 they followed the railroad, reaching Summit by noon, but the quick progress did not reduce the damage done to the railroad. From Gills Plantation to Summit the raiders burned every bridge, trestle, and water tower on the line. At Bogue Chitto they burned the depot, its contents, and 15 railroad cars. At Summit they destroyed twenty-five more railroad cars, a large quantity of Confederate government sugar, and the depot building. The line was so thoroughly wrecked that it could not be used again until after the war ended.

Grierson’s men also found a large quantity of rum buried under a boardwalk. Fortunately Grierson learned of the cache before the men could liberate any significant quantity of the high-proof liquor. The barrels were smashed, rum watering the street. Grierson also discovered a significant amount of pro-Union sentiment in Summit among both its white and black inhabitants. Leaving Summit, Grierson struck off southwest, abandoning the railroad. The brigade rode another 15 miles before stopping for the night at the Spurlack Plantation, near Liberty, Mississippi.

Grierson’s move away from the railroad proved prescient. Richardson made slow progress – mainly due to the destruction of the railroad wrought by Grierson’s men – but reached the vicinity of Summit by midnight. Believing Grierson was encamped in Summit for the night, he prepared to launch an ambush at 3:00 am – to catch the Yankees sleeping. All Richardson’s attack did was disturb the townspeople’s sleep.

Adams had also moved south quickly. By nightfall he was within ten miles of Spurlack’s plantation. To further complicate Grierson’s escape, the Ninth Tennessee, hot on Grierson’s trail, had arrived in Osyka.

As dawn broke on May 1, two obstacles stood between Grierson’s cavalry and safety – the Tickfaw and Amite Rivers. Grierson feared that the Confederate net was drawing tight around him. His scouts had provided reports of the converging Confederate columns and he resolved to ride hard for a bridge across the Tickfaw, but felt the need to further confuse the Confederates as to his intentions. As on previous days, he sent off small parties to make demonstrations towards Magnolia and Osyka – to again focus Confederate attention on the railroad.

Shortly after starting, the main column came across an old civilian heading for a mill. The travel-stained clothing worn by the Yankees was unrecognizable, and the man took the troopers for a Confederate unit seeking Grierson. Without correcting the man’s mistake Grierson hired him as a guide. It was a worthwhile expenditure of Confederate money and a captured horse, because the old man knew the countryside intimately, and the column made fast progress. However, as they neared the bridge over the Tickfaw they saw fresh and numerous horse tracks on the road to Osyka. Realizing this indicated that a significant enemy force was in the area, Grierson halted the column and sent scouts – dressed in Confederate butternut, as usual – to reconnoiter.

The scouts encountered a patrol of the Ninth Tennessee heading toward the bridge. While they were talking to the patrol, some other Confederate soldiers, straggling, blundered into some troopers of the Seventh Illinois and realized they were Yanks. A brief exchange took place, with the stragglers quickly captured. When the Confederate patrol investigated, they were told that it was an accidental exchange between two friendly units, and then were captured when they lowered their guard.

However, the exchange was also heard by Grierson’s advance guard, led by Lieutenant Colonel Blackburn, approaching Wall’s Bridge across the Tickfaw. Blackburn assumed the firing meant that their presence had become known to the Confederates, and charged across the bridge, calling the scouts – all he had with him – to join the charge. Blackburn’s action proved ill advised. The scouts by themselves – dressed in butternut outfits – could likely have taken the bridge by bluff and surprise. The presence of a Union officer – in a Union officer’s uniform – rushing the bridge gave the game away.

The defenders opened fire. Within a few minutes a firefight developed that left Blackburn fatally injured and two of the scouts, including Surby, badly wounded. Worse still, Blackburn and the scouts – injured and otherwise – were pinned down under enemy fire. The rest of the advance guard, one company of cavalry, rushed up to rescue their comrades, and the skirmish grew.

The bridge was held by three companies of the Ninth Louisiana Partisan Battalion – part of the force sent north with the Ninth Tennessee Cavalry to Woodville by Garner. They had gone on ahead to secure the bridge and soon pinned down the advance guard. Grierson and Prince heard the firing. Grierson sent a battalion of the Seventh Illinois to the bridge, and split the Sixth Illinois, sending half to ford the river on both flanks.

The superior numbers of the Seventh failed to force the bridge, but Grierson sent two of the Woodruff guns to support the attack. They soon deployed and began shelling the Partisan Ranger cavalry. The Louisiana irregulars reacted much as the Mississippi state forces had when Hatch’s Woodruff gun opened up. They broke and ran. Once started, they did not stop until reaching Osyka.

While bloody, the fight was short, so short that Grierson’s civilian guide failed to realize what had happened. He congratulated Grierson on driving off the Yankees, took his horse and cash, and returned to his original task. The fight left one of Grierson’s men dying and three, including Sergeant Surby, too badly injured to travel. Grierson was forced to leave them at a plantation, along with his surgeon and a trooper who volunteered to remain. Surby’s companions changed him back into a Union uniform, and one took the diary Surby had made of the raid. One of the wounded men later died. Surby, the doctor, and other two troopers were taken prisoner. Yet despite the cost, the way to Baton Rouge was now open – if only briefly. Gardner’s troops were rushing to block passage over the Amite, and Adams and Richardson were in hot pursuit. They had joined forces in early afternoon at Magnolia, Mississippi, where both had gone seeking Grierson. By 10:00 pm they were at Osyka, and they headed south until 2:00 am, when they finally paused to rest.

When Lieutenant Colonel Blackburn learned that Confederate pickets were guarding the bridge over the Tickfaw River, he rashly charged across, supported by only a few scouts. The Confederates waited until the force was across the bridge before opening fire, mortally wounding Blackburn and one other scout, and injuring two others. The attack force was pinned down by enemy fire, and a general engagement developed in an effort to rescue the trapped men. It required artillery support from the Woodruff guns to end the stalemate that developed.

The federal cavalry camp where Grierson’s men stayed after their arrival at Baton Rouge. (AC)

Grierson made his first contact with Gardner’s forces when the brigade encountered three companies of scouting cavalry near Greensburg at 2:00 pm. The Sixth Illinois drove them off, and Grierson broke contact. He reached William’s Bridge across the Amite at midnight – ahead of Gardner’s men – and was soon across the unfordable river.

But Grierson sensed that it was no time to stop. The troopers rode doggedly toward Baton Rouge all night. By dawn they were at Greenwell Springs, where they found the camp of one of the Confederate cavalry units hunting them. Led by the Sixth Illinois, the brigade forded Sandy Creek and captured the camp, taking 40 prisoners. They destroyed the camp – 150 tents, ammunition, stores, and guns – before resuming the march.

There was one final river between Grierson and Baton Rouge – the Comite. It could be forded, but the three fords were guarded by Bryan’s cavalry – a company that was part of Miles’ Legion. Pickets were at two of the fords, with the bulk of the company and its camp at Robert’s Ford. Because of the Comite’s proximity to Baton Rouge, the Confederates’ attentions were focused in that direction – to the south and west – rather than the bank from which Grierson’s men were approaching. Led by the Seventh Illinois, the Union cavalry swept across the ford and captured the Confederate camp and company. Surprise was so total that only one man – an officer who hid in the branches of a moss-covered oak – escaped the Yankees.

At about the same time, Richardson and Adams were arriving at Greensburg. Richardson had sent a company of cavalry ahead to block Grierson by burning Williams’ Bridge, but that force arrived eight hours too late. While digesting this intelligence at Newman’s Plantation they were joined by Miles’ Legion, also seeking the elusive Yankees. Grierson had slipped between both groups. Adams and Richardson were soon to rejoin Pemberton, to aid the fight against Grant, at Port Hudson. Colonel Miles received orders to cover the railroad, too late for it to do any good.

Grierson, his men, their prisoners – a swarm of runaway slaves that had been attaching themselves to the marauding Yankees since Montrose, Mississippi – and extra mules, horses, and wagons accumulated en route were past the last Confederate outpost between them and Baton Rouge. Everyone was exhausted. They had ridden 76 miles without sleep since rising at daybreak on April 30, fighting four battles in the intervening hours. Rather than risking friendly fire entering Baton Rouge, Grierson halted his men at a large plantation four miles past the Comite, intending to rest and send scouts to Baton Rouge. As related in the introduction, a sleeping orderly rode into the Union lines, and General Auger, commanding Baton Rouge, sent a patrol out to investigate. Grierson and his brigade received a heroes’ welcome in Baton Rouge. It was not until 3:00 pm, following a victory parade, that the raiders received the thing they most wanted – an opportunity to have a full and uninterrupted night’s sleep. Grierson’s Raid was over.