Harrison Albright acquired a great deal of wealth, but at the end of his life he was unable to enjoy the benefits of his success. Courtesy of Greater Los Angeles & Southern California Portraits & Personal Memoranda.

1

HARRISON ALBRIGHT

Harrison Albright came to California for the same reason most people come to California—to start a new life—but he didn’t move to San Francisco, which was a metropolis even in 1900. Instead, he chose Los Angeles for his new life. At the turn of the twentieth century, Los Angeles was an unruly town with dirt roads and small-scale buildings. Few of the buildings that Albright saw when he arrived in Los Angeles would survive into the twenty-first century. The California Albright moved to no longer exists, but many of the buildings Albright designed have survived, and those buildings have created a bond with the people who inhabit the communities in which the buildings stand and link Californians to a past that has vanished. Albright is important to the architecture of California because in the city of San Diego, where Albright had his biggest impact, the buildings he designed were originally deemed too grandiose for small-town San Diego. John D. Spreckles, one of the titans in San Diego’s history, said at a 1923 dinner in his honor,

Why did I come to San Diego? Why did any of you come? We came because we thought we saw an unusual opportunity here. We believed that everything pointed to this as the logical site for a great city and seaport. In short, we had faith in San Diego’s future, so we cast our lot here. We gave our time and strength and our means to help develop our city, and naturally, our own fortunes. And I, for one, have never lost my first faith in San Diego.1

Harrison Albright acquired a great deal of wealth, but at the end of his life he was unable to enjoy the benefits of his success. Courtesy of Greater Los Angeles & Southern California Portraits & Personal Memoranda.

The film Field of Dreams basically said the same thing with these seven words: “If you build it, they will come,” and they did. Many of the key buildings that are the foundation for the city of San Diego, that give it its inherit character, are Harrison Albright buildings.

Albright was born in Shoemakertown, Pennsylvania, on May 17, 1866. His parents were Joseph and Louise (née Jeannot), and he had two elder sisters, Alice and Emma, which made Harrison the youngest in the family. He attended local public schools, the Pierce College of Business and the Spring Garden Institute, but there is no evidence that he received a degree in architecture or engineering.

Albright opened an architectural office in Philadelphia in 1886, and it remained opened until 1891, when he married Susie J. Bemus. The couple would eventually have three children—Anna Louise, Catherine and Harrison Jr.—but first, he and his wife moved to Charleston, West Virginia, where he opened another office and remained in business there from 1891 to 1905. Albright designed two buildings of some note before he arrived in Los Angeles in 1905: the annex for the capitol in Charleston and the West Baden Springs Hotel in Indiana. The West Baden Springs Hotel (1902) was referred to as “the eighth wonder of the world” during its heyday, and while it was abandoned from 1983 to 1996 and put on Preservation magazine’s “endangered list,” it was saved by the Historic Landmark Foundation of Indiana and is no longer threatened. It is likely U.S. Grant Jr. saw one or both buildings and they were the basis for Harrison Albright’s selection for the U.S. Grant Hotel. At the very least, Grant knew of them—it seems improbable that Albright would have arrived in Los Angeles as an unknown and within months acquired a huge commission from Grant to design the landmark U.S. Grant Hotel.

U.S. GRANT HOTEL

It was on May 10, 1905, that the Los Angeles Times reported San Diego’s Horton House hotel, built in 1872, would be demolished and a new hotel would be erected in its place. The man behind the new hotel was Ulysses S. Grant Jr., the former president’s son. Demolition was set to commence in July 1905, and while Grant was being urged to name the hotel after his father, he favored naming the new hotel after the old one.

Yet it took more than five years for the building to be completed from the time it was originally announced. Harrison Albright had estimated it would take a year to build, but it didn’t open until October 15, 1910. The principal reason for the slow progress was Grant’s failure to raise enough cash for the building’s construction prior to the groundbreaking. Grant had continual problems throughout the construction of the building—all due to lack of money.

U.S. Grant Hotel. According to the Weekly Union newspaper, the hotel’s prominent features were its perfect lines and “gigantic massiveness.” Courtesy of American Architect.

Grant originally found funding with the National Sureties Company and later acquired more capital through Colonel A.G. Gassen and Ralph Granger. Gassen bought certain properties Grant owned in the San Diego area, which provided Grant with ready cash. Granger invested $350,000 that he obtained from the sale of property he owned in Brooklyn, New York. During construction, though, the U.S. Grant Hotel was a money pit. When Carl Leonardt, the Los Angeles contractor who received the concrete contract, wasn’t paid in a timely manner, Leonardt sued for failure to provide payment. Lawsuits were then filed by numerous parties connected with the construction, and all work ceased. What followed over the subsequent years were long periods of time when no work was done on the hotel. It sat on Broadway, between Third and Fourth Avenues, in a state of incompleteness. As year after year passed, the citizens of San Diego viewed any announcement regarding the resumption of construction on the hotel with skepticism.

This was not Albright’s only project during this period. In 1906, Albright designed and saw to completion, in an industrial area of Los Angeles, the Santa Fe Freight House for the Santa Fe Railroad. This building still stands in an altered configuration, with the dock area enclosed, and is now used by the architectural school SCI-ARC as its main building. In the following year, 1907, Albright designed the Spreckels mansion for John D. Spreckels in Coronado. Coronado was a tony suburb of San Diego, and the Spreckels mansion was on the market in 2017 for $15.9 million. Spreckels must have liked Albright because he would later hire him for two other large San Diego commissions: the Union Tribune Building and the Spreckels Office and Theater complex. But before either of those was erected, 1907 saw one other major building from Albright—the Consolidated Realty Building on the corner of Sixth and Hill Streets in downtown Los Angeles. It wouldn’t be finished until 1910, but this wasn’t due to lack of funding.

The Spreckels mansion. From The Man: John D. Spreckels.

In September 1908, Grant found another financial backer by the name of Hulett Clinton Merritt, a “well-known capitalist”2 and real estate investor from Pasadena. Merritt was originally from Minnesota and helped create the Lake Superior Consolidated Iron Mines, also known as the Merritt-Rockefeller syndicate. In 1901, Merritt and Rockefeller sold their holdings to U.S. Steel for $81 million. When Merritt invested money (pocket change for him) in the Grant Hotel project, he did it to help his friend, not U.S. Grant, but rather John H. Holmes, who was also from Pasadena.

Merritt enjoyed investing in real estate. In the panic of 1907, Merritt bought two of the best corners in downtown Los Angeles, according to Notables of Southwest, so he had enough spare cash to gamble on Holmes. John H. Holmes, who had worked at the Green Hotel in Pasadena for nineteen years, would eventually lease the Grant Hotel from the owners and was referred to in one newspaper account as “the commander in chief ” of the Grant Hotel.

In the spring of 1909, it looked like the hotel might never be finished. Claims against the corporation behind the hotel hovered around $80,000, and construction was at a standstill. In June 1909, Leonardt was in court suing for $140,000 he claimed was owed him. Grant countered by alleging that Leonardt’s work was unfinished and in some places substandard. Grant also alleged “that the contractor [Leonardt] entered into collusion with Harrison Albright, the defendant’s architect, to reengineer the building and to change the specifications agreed to by plaintiff and defendant.”3

Carl Leonardt was the contractor for the Los Angeles County Hall of Records, U.S. Grant Hotel, the (old) Orpheum Theater in Los Angeles, the Pacific Electric Building, the Hotel Green in Pasadena and the Hamburger Building. Courtesy of Notables of the Southwest.

Grant’s accusations did not hurt Albright’s reputation, as this was not Albright’s only project. His other buildings went up without any complications or delays. The Consolidated Realty Building took three years to build but only because more floors were added during construction as the Sixth and Hill location became more desirable to potential tenants.

In July 1910, it was reported in the San Diego Union that Grant

feels what he regards as a lack of interest in the hotel project on a part of a number of businessmen in San Diego. It is said he told an intimate friend before leaving the city last Saturday that he was much disappointed in the reception of his cherished scheme by the better class of business men of San Diego and by the failure of the public in general to appreciate the importance of the big hostelry’s relation to the upbuilding of the municipality.4

At this point, Louis J. Wilde entered the picture. Wilde was born in Iowa City, Iowa, arrived in Los Angeles in 1884 and moved to San Diego in 1903. He was president of San Diego’s American National Bank and responsible for who stayed and who left the project. Albright stayed on as architect, and Wilde convinced Grant to turn over the construction of the hotel to a board of trustees—a board of which he was president. The board of trustees became promoters of the project, and the banks that the trustees represented sold bonds to raise the capital to finish the hotel. Grant seemed to lose interest in the venture soon after he transferred control of the project. Yet he really had no choice. If he hadn’t agreed to Wilde’s plan, it is likely the hotel would have been put into receivership and Grant would have ended up bankrupt.

Wilde’s concern for the project could have been based in alleviating the huge eyesore that sat in the center of downtown. As a leader in the small community, Wilde may have felt obligated to take charge of the problem and relieve the city of the embarrassment that Grant’s incompetence had created, but Wilde could have seen it as an opportunity too—to swoop in and take control of a project that, when completed, would generate a great deal of money as the city of San Diego grew.

Grant received $1 million in mortgage bonds for his stake. In the summer of 1910, the Los Angeles Times reported, “Mr. Grant has severed all connection with the costly hotel that bears his name, and that a new corporation, known as the U.S. Grant Hotel and Office Building Company, has taken over the valuable property. Mr. Grant has no connection with this company, though it bears his name.”5

Los Angeles’ Barker Brothers received the contract to furnish the hotel. The contract included furnishings for all 437 rooms, including the public spaces, along with linens, glassware and silver. The furniture cost was estimated to be in the $200,000 range, though the final cost was $250,000. The contract was hammered out by an agent representing the hotel’s owners; the hotel’s lessee, John H. Holmes; and a Barker Brothers representative, W.A. Barker.

Then, on October 1, 1910, Louis J. Wilde acquired a 50 percent stake in the hotel. The Evening Tribune wrote,

The entire arrangement will work a benefit for all interests in the big establishment. It puts the hotel bonds on a perfectly sound basis. It preserves Mr. Grant’s personal estate which it is said was in jeopardy and would have been sold at a great loss to meet claims. It puts the operating company on a firm footing and generally places the hotel in an excellent condition for the formal opening.6

The official grand opening took place on October 15, 1910, with over six hundred invited guests. U.S. Grant Jr. did not attend the event. Instead, he sent a telegram to Wilde: “My congratulations on your completing and successfully opening Grant Hotel. Hope honors will be accorded you for stupendous work, finished against great difficulties and opposition which disheartened me.”7

Mr. and Mrs. Wilde were the first individuals to sign the guest book, and then a signed slip of paper with U.S. Grant Jr.’s signature was pasted in.

It is unclear why Harrison Albright was not included in any of the extensive newspaper lists of opening night attendees, but it doesn’t appear Albright attended the event. He may have been exhausted from the project and glad it was over. The difficult memories he had of the building’s construction and the accusations by Grant may have made the decision not to attend an easy one.

Originally, the hotel had 420 guest rooms. It also had 8 bridal suites on the second floor, and the ballroom on the ninth floor could accommodate 1,200. The final cost of constructing the building was $1.1 million. The value of the land was placed at $600,000, so the total cost, including the Barker Brothers furnishings, was $1.95 million. Other points of interest: there were 500 telephones in the building, four passenger elevators and four freight elevators. There were two separate pools in the basement, one for men and one for women. The estimated cost of running the hotel, every day, was $1,000, and it employed 250 people. A large oil painting of former president Ulysses S. Grant was hung over the main staircase in a place of honor. Most architectural historians classify the U.S. Grant Hotel as early twentieth-century, Beaux-Arts, classical revival style.

U.S. Grant Hotel lobby. On opening night, there was a huge crush of people to check in. Most waited patiently, while others went to one of the hotel’s cafés for a drink. Author’s collection.

A postcard view of the Bivouac Room. Author’s collection.

The only other hotel of any comparison in the San Diego area would have been the Hotel del Coronado, which was built in 1888 as a resort. The Hotel del Coronado had over seven hundred rooms, but the Grant Hotel wasn’t a resort. The Grant Hotel was for travelers and businessmen.

The Consolidated Realty Building, begun in 1907, was completed in 1910, and the Los Angeles Times praised the design: “The building, which was designed by Harrison Albright, is a monument to the progress of the streets upon which it is situated and of the growth of the city itself.”8 Originally, the building was slated to be two stories with a foundation that could support many more floors, but as the building’s location became highly desirable, more floors were added until the building topped out at six stories. In December 1909, when almost finished, the builders decided to add three more floors because the University Club stated it would rent out floors eight and nine, if built, and sign a ten-year lease, too. Said the Times, “The general prosperity of the city led the builders to alter their plans.”9

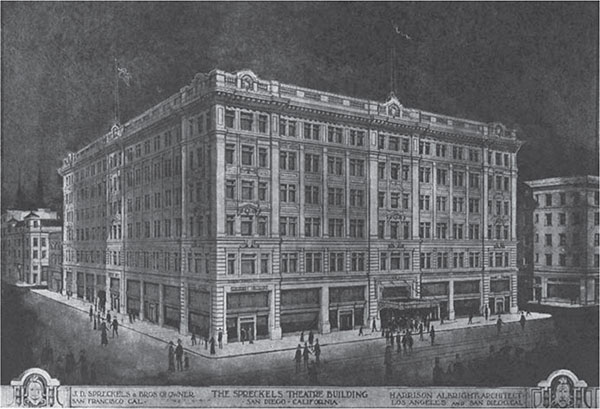

As the Consolidated Realty Building’s construction concluded, in November 1910—a month after the Grant Hotel’s opening, Harrison Albright announced the construction of the six-story Spreckels Office Building and Theater. It would be a reinforced-concrete building with a theater and occupy an entire block in San Diego, fronting D Street (Broadway) between First and Second Avenues. When it was originally announced, only the theater section, which was in the center of the building, was to be six stories; the adjoining office sections, on both sides, were designed to be two stories. However, in the final plans, the entire office building was six stories.

SPRECKELS THEATER AND OFFICE BUILDING

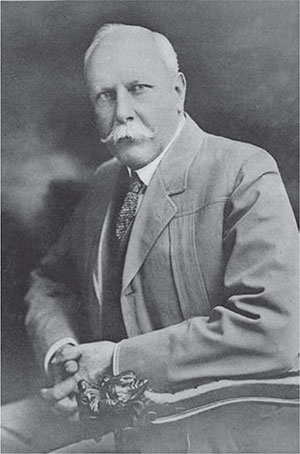

John Diedrich Spreckels, the man behind the building, was listed as a “capitalist” in many publications from the first decades of the twentieth century. (This was a common term used for businessmen with enough money to invest in large commercial real estate projects.) He was born on August 16, 1853, in Charleston, South Carolina, and attended Oakland College and Germany’s Polytechnic School. Spreckels studied chemistry and mechanical engineering and moved to San Diego in 1887. He owned many businesses, including newspapers. A short list would include the Oceanic Steamship Company, Spreckels Sugar, the San Diego Union, the Evening Tribune, Coronado Water Company and the Hotel del Coronado. Spreckels didn’t necessarily have an interest in theaters, but he did have an interest in being a civic booster and providing San Diego with the amenities that would help it grow. Spreckels built the city’s streetcar lines with his own money and stated he always invested his money in new projects to protect the money he had already invested in previous projects: “Well, the aim of my life has been the building up of San Diego. Men like me get our reward in the very activity of doing, or of trying to do, big things. It is my life.”10

The office building took two years to complete, and the stated cost for the land and the building was reported to be $1 million. When it was completed, the six-story office building was the largest in the city of San Diego. The theater opened on August 22, 1912, with a show called Bought and Paid For; it was brought from New York but scheduled to play at the theater for only two days. On Sunday, August 25, a Gilbert and Sullivan festival began with performances of The Mikado, The Pirates of Penzance and H.M.S. Pinafore. For the theater’s first season, the other productions booked included the Metropolitan Opera, female impersonator Julian Eltinge and Dustin Farnum in The Littlest Rebel.

John Spreckels requested the theater have 1,915 seats to commemorate the year San Diego would host the Panama-California Exposition. When built, the auditorium was seventy-two feet deep by eighty-eight feet wide. The stage was eighty-eight feet wide by fifty-two feet deep. The walls and ceilings of the lobby, box office, elevator recess and staircases were all finished in Pedara onyx from Mexico. The San Diego Union reported the plasterwork in the theater was “highly decorated in the most lavish manner consistent with good taste.”11 There were no pillars to mar views because the balcony was suspended from the load-bearing walls with the aid of huge steel beams. Surprisingly, a great deal of newspaper text was devoted to the theater and lobby lighting, and “the refined glow of electric lights” was much written about and made possible because of “the rapid development of the past few years in electrical science.”12 The painting above the proscenium arch depicts Neptune in a chariot bringing prosperity to San Diego. The allegorical paintings in the ceiling’s domes depict Dawn, Air, Earth, Water and Fire painted by Emil T. Mazy of Los Angeles. When the theater opened, a large basement under the theater contained an orchestra pit, a stage pit, dressing rooms, toilets, a restaurant and a kitchen. The restaurant was accessible from D Street through two large staircases.

Spreckels Theater and Office Building. The new theater was seen as an advertisement for the city and an attraction for winter tourists. From the Year Book: Los Angeles Architectural Club, 1911.

The San Diego Union pointed out that behind all the attractive interior theater decoration was not a “flimsy pine framework inviting a torch of flame to create instantly an awful deathtrap”13 but instead walls, beams and ceilings made of concrete. The newspaper stressed that the theater came equipped with “six independent side exit doors equipped with panic bolts to open outward with the slightest pressure from within.”14 It also had automatic sprinklers above the stage and a “curtain of steel” lined with vitrified asbestos that could be lowered in twenty seconds to keep the audience safe from any fire on the stage.

Architect Irving Gill attended the theater’s opening and stated,

The acoustics of the auditorium leave nothing to be striven for by builders of the future, further than a reproduction of the effects produced here. It would be a great benefit especially for architects if the world’s greatest authority on acoustics could come to San Diego and make a study of this auditorium and write critical analysis of its structure. I extend congratulations to architect Albright on the results he has accomplished.15

Harrison Albright proclaimed on opening day, “San Diego makes another long stride towards metropolitan distinction with the opening of the Spreckels Theater tonight.”16

John Spreckels was frequently accused of trying to turn San Diego into his own personal town. From The Man: John D. Spreckels.

The population of San Diego grew rapidly from seventeen thousand in 1900 to fifty thousand in 1912—more than a threefold increase. It was a new town and seemed to be suffering from an inferiority complex from what can be gleaned from the Evening Tribune. The newspaper quoted John Spreckels the day before the theater opened:

Too many of us think of it as ahead of the town just as we thought of the U.S. Grant Hotel. Just so, it is not ahead of the town; the town is ready for it now, needs it and its growth has been hampered without it. Let’s get that fixed in our minds; the Spreckels Theater is none too big and none too good for San Diego right now.17

In 1915, Albright lived at 618 South Benton Way in Los Angeles, and his office was in the Laughlin Building, which was located at 315 South Broadway, also in Los Angeles. By 1930, the family had moved to 708 Imperial Avenue in San Diego. Before he retired, Albright was described in a 1921 article in the Los Angeles Herald as a wealthy property owner with extensive real estate holdings in Los Angeles and San Diego Counties. At that time, his family filed a petition stating that he was incompetent to manage his affairs and requested the Title Insurance and Trust Company be appointed as guardian of his estate.

In a letter to the Albright’s land agent, Colonel Ed Fletcher, from Woodruff & Shoemaker, attorneys and counselors at law, dated May 3, 1922, the law firm wrote: “As you have been informed, Mr. Albright has been declared incompetent and the Title Insurance and Trust Company appointed the guardian of his estate.”18 Susie Albright wrote to Fletcher too and said, “My husband has been under the care of one of the oldest and best brain specialists in this city and has improved very much during the past week.”19 Albright officially retired from his practice in 1925 and was listed as an invalid in the 1930 census. He died on January 3, 1932. He was survived by his wife, Susie, and his children, Anna Louise, Catherine and Harrison Jr.