Hollywood Athletic Club. Author photo.

7

MEYER & HOLLER: THE MILWAUKEE BUILDING COMPANY

The Milwaukee Building Company, which was founded by Mendel Meyer in 1906, went from being a startup to enormously successful and then it slowly faded away. Philip W. Holler’s rise within the Milwaukee Building Company from “no role in the company” to vice president to “no role” again parallels the company itself.

Philip W. Holler was born on January 4, 1869, in Indiana. His parents, both Indiana natives, were Christian and Mary, and Holler had an elder sister also named Mary and a younger brother Ed. Holler was a farmer in Indiana and married Lily Sherfey on November 15, 1894. Within a few years, the couple had two sons, Wesley and Albert, and the family moved to Los Angeles in the first decade of the twentieth century. According to census records, they were still married in 1910, but sometime between 1910 and 1913, Holler divorced Lily, and he married Mary J. Feerrar on September 15, 1913. This marriage did not last either. According to a newspaper report from March 1919, Holler, “vice president of a large building company,” was charged with desertion by his second wife, Mary Holler, “after a married life of six years.”133

Mendel Meyer was born on October 7, 1874, in Los Angeles. His parents, both from Germany, were Samuel and Johanna. Meyer had a brother named Gabe and a sister named Rose. According to his obituary, Meyer was a graduate of the “old Los Angeles High School,” but Meyer never attended college or received a degree from any institution of higher education.

Meyer married Mable M. Gray in Los Angeles on January 4, 1915. He was forty years old when he married for the first time. Mable had been married before and had a son named Miles.

Two major projects the Milwaukee Building Company undertook before 1920 were the Charlie Chaplin Studios in Los Angeles and the Thomas Ince Studios in Culver City. Announced on October 16, 1917, the Chaplin project was situated on five acres of land Chaplin bought from R.S. McClellan. Sunset Boulevard was the lot line on the north, La Brea Boulevard on the west and De Longpre Street on the east. Chaplin’s purchase included the McClellan mansion, which was located near Sunset Boulevard, and Chaplin planned to use it as his home. Orange trees covered the rest of the acreage. Six quaint one- and two-story English-style buildings were designed to run down La Brea Boulevard, while the sound stages and dressing rooms were built away from the street and out of view of motorists. The cost was approximately $100,000. Chaplin began to use the studio at the end of January 1918.

The Chaplin Studios are currently the home of the Jim Henson Studios.

Announced on November 17, 1917, the Ince Studios project was bigger than the Chaplin project. It involved eleven acres, twelve to eighteen concrete buildings that included open air and glass stages, a swimming pool and an outlay of between $200,000 and $500,000. The acreage Ince bought fronted Washington Boulevard in Culver City. Ince stated he was leaving his oceanside studio, out near Malibu, because he had become tired of having to deal with the low cloud cover over the studio, which caused delays in shooting.

The Ince Studios were ready by Christmas 1918, but Thomas Ince would only use his namesake studios for six years before his unfortunate death, which was the result of a trip aboard William Randolph Hearst’s Oneida in 1924. Producer David Selznick eventually moved onto the Ince lot, and the Ince administration building can be seen in the opening credits of Gone with the Wind. In 2014, the studio lot sold for $85 million to Hackman Capital Partners, an investment firm.

The team of Meyer & Holler was able to design and construct these pre1920s film studios quickly, but that’s not all the firm did. It also provided interior design services and arranged building loans for clients. The loan aspect of the business would be the duo’s undoing and would lead to the company’s collapse when a famous film director sued because he claimed he had been cheated.

Before that happened, the Milwaukee Building Company had a prosperous decade in which it constructed three Hollywood landmarks.

THE HOLLYWOOD ATHLETIC CLUB

In September 1921, plans to build the Hollywood Athletic Club were announced at the Hollywood Public Library following a meeting of the charter members of the club. The members stated they wanted to build an athletic club somewhere between Cahuenga and Highland and probably on Sunset. The total outlay the club planned to expend was $200,000, which included the cost of the land.

By the following April, the Hollywood Athletic Club had signed up 635 members with a goal of reaching a membership of 1,000. Leadership hoped to pick up more members by persuading local businessmen and prominent members of the community to join. Plans for the new building were drawn up and completed by the Milwaukee Building Company. The design was in the “Italian villa style of architecture, which both the architects and officials of the club believe is particularly adapted to this country.”134 The new Hollywood Athletic Club would have 200 feet of frontage on Sunset Boulevard and 157 feet along Hudson Avenue. The plot, purchased for $35,000, had increased in value and was worth $50,000 a few months later. Amenities in the new facility according to the original plans would include a gymnasium, handball courts, “swimming tanks,” lockers, showers, a barbershop, banquet halls, reading and writing rooms, a café, a billiard room and lounge rooms.

It was noted in a Times article that Meyer & Holler “have the contract for architectural design, engineering, construction, decorating and furnishings. All furniture, draperies, carpets and lighting fixtures are being specially designed, and with infinite care is being taken the interior decorations, the object being to produce harmony in design, furnishings and color scheme.”135

By December 1923, construction had been completed. The measurements had changed on Hudson Street with the frontage increasing from 157 feet to 210 feet. The athletic club was two stories with a nine-story tower, which contained fifty-four rooms for “bachelor” members for a grand total of eleven stories.

The exterior of the building was cream-colored stucco, and it was graced with a red tile roof. When built, the interior rooms had a Florentine design, and some of the main rooms were copies of Florentine rooms in European palaces. The seating capacity in the dining room was three hundred, and a modern Pompeian decoration was used in the game room. The final breakdown of cost was $200,000 for the land, which had increased six times, from what it had originally cost, and $800,000 for the building and furnishings for a grand total of $1,000,000.

Hollywood Athletic Club. Author photo.

Hollywood Athletic Club grill with initials of the club over entrance. Author photo.

Opening day was January 12, 1924, for members, their families and friends. A Hawaiian orchestra provided music to accompany the buffet luncheon, which was held in the dining room, and notable Hawaiian Duke Kahanamoku was featured in an aquatic exhibition. Part of the opening day festivities included an exhibition on the Roman rings, a side horse exhibition, tumbling and acrobatics, feats of strength, horizontal and parallel bar work, swimming, water polo, diving and comedy diving. Comedy diving was about horseplay and gimmicks. It included men dressed in women’s bathing attire, jump ropes and diving board mayhem, with the diving being similar to a pratfall.

The Hollywood Athletic Club won an award in 1925 from the Southern California chapter of the American Institute of Architects in the category “multiple dwellings of the club type.”

Meyer & Holler’s status in Los Angeles went up even higher with their next major project.

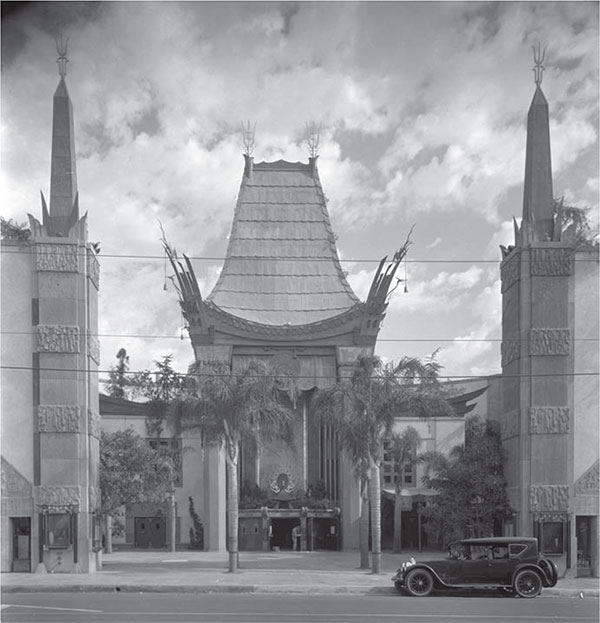

THE CHINESE THEATRE

The most famous theater in the world might be the Chinese Theatre, but when the theater was first announced, it was clouded in secrecy. Sid Grauman, who had built the Hollywood Egyptian Theatre in 1922, was mentioned as being the man behind this latest theater project in Hollywood, but that was one of the few details offered. The future location of the theater was given, on Hollywood Boulevard between Orange Drive and Orchard Avenue along with the names of the architects, Meyer & Holler, who would handle the architecture, construction, decoration and engineering. Yet prominently situated in the initial announcement was the unusual statement that the architectural details of Grauman’s new theater would remain undisclosed.136

At the groundbreaking ceremonies held on January 5, 1926, Anna Mae Wong, whose credits include The Thief of Bagdad (1924), handed Norma Talmadge, one of the famous Talmadge sisters, a spade to turn over the first mounds of earth for the Chinese Theatre. Joseph M. Schenck, head of United Artists, and Sid Grauman each said a few words as part of the festivities, and after they spoke, Chinese women immediately served everyone tea.

By October 1926, the style of the building had become a well-known secret, and many newspaper articles openly referred to it as Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. One article stated that Meyer & Holler had set up a laboratory, on-site, to produce miniature models of the sculpture that would be placed around the theater. The models were studied for correctness in scale before the large versions were cast.

Also noted in the same newspaper article, not directly but indirectly, was that Grauman wanted the theater to be authentic and he consulted with those who had knowledge of Chinese culture. Liu Yu Chang, a renowned expert on Chinese art, looked over the models at Grauman’s request and approved them.137

Yet secrecy still prevailed. The entrance to the forecourt was closed off and hidden behind a high screen, which made only the upper portion of the theater visible from the street. An article titled “Secrecy Marks Building” relayed that the reason everything was done in secrecy was because Grauman wanted to provide his first night’s audience with spectacle and surprise.138

With the opening of the theater growing near, Grauman and Cecil B. DeMille announced the opening attraction would be DeMille’s King of Kings featuring H.B. Warner, Joseph Schildkraut, Bryant Washburn and Sally Rand.

Times writer Marquis Busby gushed three days before the theater’s opening that the event was one of the most important affairs in recent theatrical history.139 Much of what Busby wrote was hyperbole, but some of the information he relayed was interesting. Busby stated the Chinese’s stage, which had the dimensions of one hundred feet wide by forty-six feet deep, was, at that time, the third-largest stage in the United States. Only the stages of the New York Hippodrome and the Los Angeles Shrine Auditorium were bigger. Busby wrote the Chinese’s pagoda’s roof was ninety feet above the forecourt. The theater had an independent power plant, which provided electricity for the theater along with its own heating and ventilation system. The walls that encircled the courtyard were forty feet high. The theater seated 2,200 people on a single floor. This was Grauman’s fifth theater in the Los Angeles area. His other four theaters were the Million Dollar, Rialto and Metropolitan (all in downtown Los Angeles) and the Hollywood Egyptian, which also was a Meyer & Holler building.

Chinese Theatre, circa 1930.

Chinese Theatre. Courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California.

The premiere and grand opening took place on May 18, 1927. By 5:00 p.m., fans waiting on the sidewalks were ten deep, and by 9:00 p.m., it took half an hour to walk a single block. Norma Talmadge, at Grauman’s request, put her hand and footprints in cement on opening night and started a tradition that continues to today. Inside the theater, D.W. Griffith spoke first and regaled the audience with a history of the theater. Not the Chinese Theatre, but of the history of the theater in general, and how through the dark ages, when there was no theater, mankind withdrew into itself. Cecil B. DeMille, who spoke about his production of King of Kings, followed Griffith. After he finished, he handed the proceedings over to Will Hayes, who was there to introduce Mary Pickford. Pickford, who was dressed in a golden gown of sequins, was handed an electric button by Hayes. She looked at it and smiled before she pushed the button. With that gesture, America’s sweetheart formally opened the Chinese Theatre.140 It is not clear exactly what she opened since everyone was already in the theater, so the “button pushing” may have been a symbolic gesture, but she could have opened the curtain.

Edwin Schallert, who covered the event for the Times, said the theater was filled with beauty and he expected tourists would make a special effort to see it.141

D.W. Griffith wrote to Grauman a few days later to express his admiration. He said rather imperially that artists, or someone with an artist’s soul, were the only ones who could truly appreciate the monumental beauty of the theater. Then he wisely predicted that the theater would be world famous.142

The Chinese Theatre was declared Los Angeles Historic Cultural Monument No. 55 on June 5, 1968.

HOLLYWOOD FIRST NATIONAL BANK

The Hollywood First National Bank is on countless postcards from the 1920s, 1930s, 1940s and 1950s. Whenever a photographer wanted a photograph looking down Hollywood Boulevard, he or she usually included this bank as a demarcation point. It was originally known by two different names: Pacific Southwest Trust and Savings Bank, or Los Angeles First National Trust and Savings Bank.

The first mention of this landmark bank is in a four-paragraph newspaper article dated July 24, 1927. The article reported that rapidly growing Hollywood would soon have a new $750,000 building designed for the Pacific Southwest Trust and Savings Bank and it would be located on the northeast corner of Hollywood and Highland.143

A follow-up article in October still referred to the bank as the Pacific Southwest Trust and Savings Bank. This article stated that the old bank had been demolished, the site had been cleared and excavation work was set to begin. The architectural firm Meyer & Holler is mentioned as the designers of the building and in charge of the new bank’s construction. It reported the building would be six stories and have a tower of 190 feet. Gladding-McBean & Co. was awarded the contract for the terra cotta, and it was to supply 150 tons of terra cotta for the facing. Above the main floor, the plans called for 127 offices of various sizes; the building would be stepped back and be steel framed. This article erroneously reported the building would be located on the northwest corner of Hollywood and Highland.144

Six weeks later, in a lengthy article that discussed various bank projects in the Los Angeles region, the Meyer & Holler bank is mentioned, but this time it is referred to as Los Angeles First National Trust and Savings Bank.145 Everything else rings right though: it’s located at Hollywood and Highland, it’s a bank and office building, the previous bank was torn down, it’s steel and concrete, it’s six stories and has a 190-foot tower, the façade would be terra cotta and the design allows for flood lighting at night.

First National Bank of Hollywood entrance pediment. Note the bees and honeycomb. Author photo.

First National Bank of Hollywood tower with eagles, cranes, lions and pineapples. Author photo.

First National Bank of Hollywood at the corner of Hollywood and Highland Boulevards. Author photo.

On July 1, 1928, less than a year after announced, the building was completed. In a newspaper article accompanied by a photo, it is referred to as the Los Angeles First National Trust and Savings Bank. Tenants had already moved into their offices, but the Hollywood branch of Los Angeles First National would not have its formal opening until September 8 at the earliest. The Times declared, “The building, because of its tower construction, is one of the outstanding edifices in Hollywood.”146

THE KING VIDOR JUDGMENT

In the early 1930s, the Milwaukee Building Company had to deal with an unfortunate situation that appeared from out of the past. King Vidor, the director of The Big Parade (1925), The Crowd (1928) and eventually The Fountainhead (1949), had filed a lawsuit against the Milwaukee Building Company. In the early 1920s, Vidor, along with his father, C.S., hired the Milwaukee Building Company to locate and purchase a five-acre tract of land off Santa Monica Boulevard for the purpose of building a motion picture studio for them. Vidor and his father claimed they were overcharged $32,608.20 when they undertook this venture. The vast majority of the amount the Vidors were seeking was due to what they claimed was an excessive interest rate. On May 8, 1932, superior court judge Dailey S. Stafford ruled in favor of the Vidors and awarded them $27,799.08 with interest back to September 1, 1922.147

No reaction from Meyer or Holler was recorded, but a judgment that size must have been difficult to deal with—especially in the middle of the Depression. In today’s dollars, it is equal to $496,000.

The firm of Meyer & Holler trudged along during the Depression, but the firm had lost its air of invincibility. It was like a zeppelin slowly crashing to the ground. The ruling definitely had an effect on their business. It moved from the elegant Wright & Callendar Building where it had luxurious offices for twenty years to a location on West Washington Boulevard next to the railroad tracks.

Holler lived with his sister Mary Cunningham for a time in the 1930s and then rented a farmhouse on Balboa Avenue where he spent his last years. Holler died on November 24, 1942 at age seventy-three and was buried at Valhalla Memorial Park in North Hollywood. He was survived by his sons Wesley and Albert.

Meyer was sixty-five in 1939 and retired sometime after that. It had been seven years since the King Vidor judgment, but he probably hadn’t paid it off by then. In 1939, he made only $3,421 and was living in a $60 a month apartment.

After he retired, Meyer lived in both Los Angeles and Glendale before he moved up to Santa Barbara in November 1954. Meyer lived in Santa Barbara’s California Hotel, which was owned by Meyer’s stepson, Miles. Mendel Meyer died on April 1, 1955, at eighty and was buried at the Santa Barbara Cemetery. Upon his death, Meyer left a widow, Mable Miles Meyer, and stepson, Miles R. Gray.