Julia Morgan. Courtesy of the Julia Morgan Papers, Special Collections and Archives, California Polytechnic State University.

8

JULIA MORGAN

The San Francisco Chronicle ran a short article about Julia Morgan in 1901 regarding her training in Paris. “She Qualifies in Paris as Architect” was the title. The article states, “Morgan, of Oakland, has won the distinction of being the first American woman to graduate from the architectural section of the Ecole des Beaux Arts [sic] of Paris.”148 The coursework at the École was difficult, according to the Chronicle, and while other American women had attempted to complete and graduate from the architectural program, none had succeeded.

While in Paris, Morgan received training in the office of Chaussemiche, who was a well-known architect in the city. When asked to comment on Morgan’s achievement, Chaussemiche responded,

She will make a very good architect. Her taste in ornamentation, however, will require correction. In common with her compatriots, Miss Morgan mixes styles a little too much, but this slight fault will pass away and I have no doubt she will succeed very well in her country. I would have no hesitation in confiding to her the erection of a building, as in the science of the profession she is far superior to half of her male comrades. It is true that the objection can be made that a woman cannot well climb scaffolds to oversee the work or come into contact with the laborers and mechanics but an architect’s functions do not consist exclusively of those disagreeable duties. His office work, such as preparing plans and sketches, is more important and for this women are well suited.149

She had to wait to obtain her certificate, though, because even though she finished all the coursework in two years, the École withheld her certificate, maybe, hoping she would simply go away. Not deterred, Morgan reenrolled in classes, entered an architectural competition that was underway at the École and won first prize. The school was probably annoyed with her persistence, but it must have also realized it had no alternative but to award her the certificate she had earned. When Morgan returned to the Bay Area, she went to work for John Galen Howard, who was happy with her work. He said to a colleague that he had hired a great designer who “he didn’t have to pay anything because she is a woman.”150

Julia Morgan. Courtesy of the Julia Morgan Papers, Special Collections and Archives, California Polytechnic State University.

This is the male attitude Julia Morgan had to deal with throughout her career.

Julia Morgan was born in San Francisco on January 20, 1872. Her parents were Charles Bill and Eliza Woodland Morgan. She had three brothers— Parmalee, Avery and Pardiner—and a sister named Emma. She graduated from Oakland High School in 1890 and received a bachelor of science degree in civil engineering from the University of California in 1894. She then went to Paris, at the urging of Bernard Maybeck, who was her mentor while at the University of California, and attempted to gain access to the École des Beaux-Arts, which was already under pressure to admit women. She arrived in Paris in 1896 and gained admittance in 1898, which was the first year the École admitted women to the architectural program.

With her certificate in her hand, back in the United States, Morgan struck out on her own in 1904 to become the “first woman licensed to practice architecture in California.”151 A story that reveals Morgan’s stamina and determination comes from her nephew Morgan North, who said, “She often worked seven days a week, 10 to 15 hours a day. Before she had a car and driver she used to complain that she needed only four hours sleep a night but the cable car rested six.”152

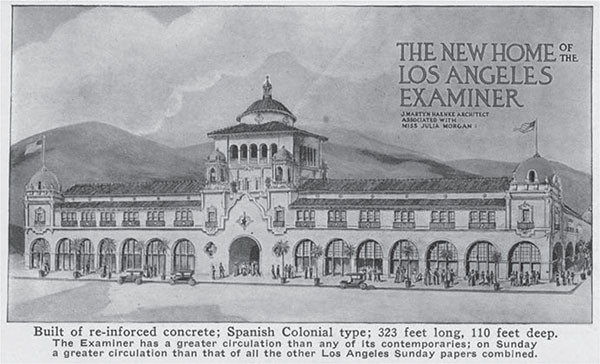

LOS ANGELES EXAMINER BUILDING

In 1913, William Randolph Hearst requested Morgan’s services for a big Los Angeles project he was about to undertake. For this project, Morgan worked with two other architects. The building is Misson in style but can be read as Spanish Colonial too. Located at the southwest corner of Broadway and Eleventh Streets, it has a frontage on Broadway of 325 feet and 110 feet on Eleventh Street.

It has roughly 100,000 square feet of floor space with a white exterior and a red clay tile roof. The land the Examiner Building sits on originally belonged to O.W. Childs, who had a homestead on the site in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The History of Los Angeles County 1880 contains an image of Childs’s home. (Note: In 1880 and up until 1913, this section of Broadway south of Tenth Street was called Main Street because between Tenth and Eleventh Streets there was a field that prevented Broadway from continuing.) Henry E. Huntington bought the Childs homestead and then resold the large parcel to a syndicate headed by Louis Isaacs, who subdivided it. Of the forty-four lots available, William Randolph Hearst bought twelve, for which he paid $1,074,325.153 Hearst handled the deal himself. He arrived on the morning of March 7, 1913, and after negotiating with Louis Isaacs for a few hours, Hearst announced his purchase and his plans to build a modern office building on the site.

Work on the Examiner Building commenced on July 1, 1913, the same day the city granted the building permit. The Alta Milling Company was the contractor. A ceremony to lay the cornerstone occurred on August 11, 1913, at 1:30 p.m. Ernest Ingold, who was president of the Advertising Club of Los Angeles, oversaw the ceremony. One of Ingold’s first duties was to escort Mayor Henry H. Rose (1913–15), William Randolph Hearst and other dignitaries from the present Examiner Building site to the future Examiner Building site.

A Los Angeles Times article from August 12, 1913, stated James R.H. Wagner, who was president of the Realty Board, “presided over the ceremonies” and introduced “several speakers,” including Ernest Ingold, Father Conaty representing the Catholic Church, Mayor Rose, James Kinney of the chamber of commerce and William Randolph Hearst.154

William Randolph Hearst’s Examiner Building. Morgan’s co-architects were J. Martyn Haenke and W.J. Dodd. Author’s collection.

Three Los Angeles brass bands, the Long Beach municipal band and a small orchestra provided music for the event. Madame Palliser did a vocal solo, and a large California state flag, with a life-size grizzly bear on it, was raised. Recently elected and sworn in Mayor Rose was thrilled with the size of the building and its purpose. Rose stated newspapers are the best boosters in the world and hoped he would be called on in the future to officiate at more ceremonies of this type. He urged everyone in attendance to write their friends around the world and tell them “This is the way California always does things,” and he invited “everybody to come to Los Angeles to help us do them.”155

When William Randolph Hearst spoke, he thanked all the appropriate state and city officials and then “apologized for not having been born in Los Angeles but explained that he did the best he could by having himself born within the state.”156

Sealed into the cornerstone were motion pictures of the event. The building was completed on November 1, 1913—a mere four months after it was begun—setting “a new record for rapid and efficient construction.”157

The Herald Examiner Building was declared Los Angeles Historic Cultural Monument No. 178 on August 17, 1977.

While Julia Morgan worked on a variety of building types over the span of her career, one type of building she returned to repeatedly were facilities for the YWCA. Morgan designed YWCA buildings in Asilomar (1913), Fresno (1922), Hollywood (1926), Honolulu (1927), Long Beach (1923), Oakland (1915), Pasadena (1922), Salt Lake City (1920), San Francisco (1930) and San Jose (1915). The YWCA’s concept of “women helping women” naturally prompted local YWCAs to search out and select a female architect to design their buildings, if possible, and many did.

Examiner Building staircase detail.

Examiner Building center section detail. Author photos.

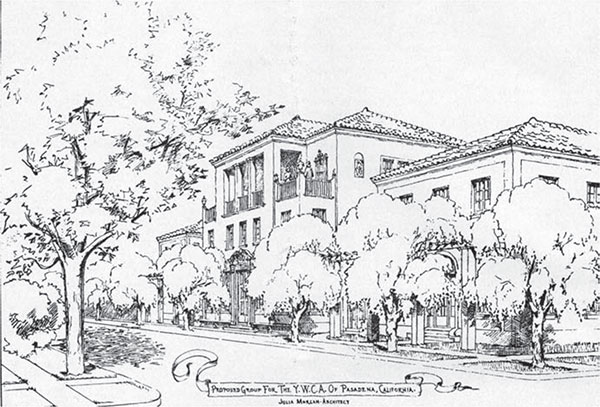

PASADENA YWCA

The Pasadena YWCA was housed in various locations before Julia Morgan designed the YWCA that stands today. Between 1905 and 1910, the organization moved four times and could have continued a nomadic existence if not for David and Mary Gamble. The Gambles came to the organization’s rescue in 1910 by purchasing a large house at 78 North Marengo Street for $15,000. In a California Southland article from 1920, the magazine noted that the YWCA owned three lots on the corner of Marengo Avenue and Union Street. Three old houses occupied the lots along with “a poorly built cottage, and a plain and homely gymnasium.”158

Pasadena YWCA house rules were simple: women up to forty years of age could stay overnight, the doors closed at 10:00 p.m., lights went out at 10:30 p.m. and there was a strict rule of “no dancing.” The Pasadena YWCA heartily endorsed the passage of the anti-liquor Eighteenth Amendment, and the board took the controversial step, for 1920, “to work with the colored community if the demand warranted it.” That same year, as the YWCA houses were not large enough to accommodate the growing demand for services, the Pasadena board launched a fundraising campaign to raise $300,000 for a new YWCA building. The board also hired Julia Morgan to serve as the architect for the facility and draw up plans.

The placement of the YWCA within Pasadena’s civic core is worth noting. The Pasadena civic core has a layout that is Beaux-Arts in design. Pasadena urban designer Vinayak Bharne has stated that “per the 1925 plan for Pasadena created by Edward H. Bennet, the north–south axis of the city’s civic core has the public library to the north and the civic auditorium to the south. On the east–west axis, city hall sits on the east and a proposed art institution/museum (never built) to the west. Julia Morgan’s YWCA has a prime location in this Beaux-Arts setup because the YWCA is one of the major buildings along this east–west axis. It must be noted, however, that the YWCA existed before Bennett’s plan. In its two-story scale, it is therefore unlike the five-story YMCA on the other side of the street.”159

Early conceptual drawing of the Pasadena YWCA. Courtesy of California Southland.

The dedication of the YWCA administration building occurred on October 9, 1922. The evening began with an all-girl processional singing “Hymn of Lights.” First Methodist’s Pastor Merle N. Smith then gave the invocation. More singing followed Pastor Smith, this time under the direction of community chorus leader Arthur Farwell. The presentation of the key to the building was the next event in the evening’s program. Local YWCA president Mrs. George R. Stewart received the key from Mary Huggins Gamble.

Gamble’s presentation invoked many responses. After all scheduled to speak spoke, everyone bowed his or her head for a dedication prayer given by Reverend Dr. Leslie E. Learned of Pasadena’s All Saint’s Church. Choral singing followed the prayer, and this singing closed the ceremony.

Not including the site, the administration building, which is three stories, cost $120,000 and is constructed of reinforced concrete. In the Spanish Colonial style, the building contains general offices, committee rooms, three clubrooms, an assembly room, a library, an infirmary, forty-six bedrooms, a cafeteria and a kitchen.

Pasadena YWCA, which is currently unoccupied. Author photo.

A feature of the building highlighted by the YWCA was its “utility room.” This was a space provided for young women to use if they were caught in a thunderstorm or their clothes become soiled in any way. In the utility room, young women could slip out of their clothes, wash them, dry them and be back on their way in no time.

A second unit containing a swimming pool and gymnasium was under construction when the administration building dedication took place. The building that housed the gymnasium and pool was threatened with demolition in the late 1980s when a plan was hatched to have the YMCA and the YWCA remain separate but use the same facility with separate entrances. The general manager of the YMCA said both YWCA buildings were obsolete and inefficient, and under a 1980s scheme, the building housing the gymnasium and pool would be demolished and the Morgan administration building enlarged. The plan failed to pass a city council vote, and before the buildings were destroyed (or altered), both were bought through eminent domain. As of this writing, they sit empty, awaiting renovation and a new use.

The Pasadena YWCA is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

HOLLYWOOD STUDIO CLUB

Mary Pickford, Constance Adams DeMille, Norma Talmadge and ZaSu Pitts were some of the women at the groundbreaking ceremonies for Morgan’s Hollywood project called the Hollywood Studio Club. Norma Talmadge, one of the biggest contributors to the venture, eagerly attended. Mary Pickford was the main speaker. ZaSu Pitts, who stayed at the club when she first arrived in Hollywood, was an enthusiastic booster. Julia Morgan made an appearance and Constance DeMille, assisted by May Parker, who was president of the club, started the steam shovel and turned the first loads of dirt.

The Hollywood Studio Club had been around since 1916 when a Hollywood librarian, Eleanor B. Jones, noticed young starlets hanging around the library “night after night in preference to attending the beach cafes or wandering around the streets.”160 After talking with the women, Jones realized that a safe place was needed for young women who came to Hollywood looking for work in the movie industry. Jones enlisted the aid of William C. DeMille, Lula Warrington and Bessie Ida Ginsberg to create such a place. The group approached several studios and the Hollywood Board of Trade and requested seed money to rent a home that could be used as a club for these young women from various parts of the country.

Hollywood Studio Club with stenciled name. Author photo.

Jones and her supporters received substantial contributions and rented an immense Greek Revival house on Carlos Avenue, but quickly, the Hollywood Studio Club outgrew the house, even though it was enormous, and needed a bigger facility. It was then that a fundraising campaign was undertaken to raise money for a new building. In an article the day before the groundbreaking ceremony, it was reported that since the YWCA had raised the funds, it would control the club.

Three months before the opening of the building, Julia Morgan spoke with Myra Nye for Nye’s What Women are Doing column.

Julia Morgan described the building as a combination of styles that included French, Italian and Spanish influences. Combined together, they could be labeled as Mediterranean with a bit of Moorish coloring thrown in. Large windows and glass doors let in the light from the street, and one set of doors led out to a patio with a fountain. There was an ancient-looking fireplace in the living room along with a private dining room, a bigger dining room that could accommodate 150 diners, a library, reception rooms and a stage, all on the first floor. The second and third floors had balconies and sixty-six rooms for the female lodgers.161

Located at 1215 Lodi Place, the club had its grand opening on May 7, 1926. The dedication, which had over five hundred people in attendance, began at 4:30 p.m. in the club’s auditorium. A prayer began the ceremony followed by remarks from Constance DeMille and film producer Charles Christie. The club was designed to be a home for female film industry employees and a social center. Each woman would receive a room and two meals a day for fifteen dollars a week. Many of the rented rooms were named after film stars who had contributed money to the building fund.

A long list of Hollywood actresses lived at the Hollywood Studio Club. Some of the biggest were Kim Novak, Marilyn Monroe, Linda Darnell and 1956 Academy Award winner Dorothy Malone. One notable writer who lived at the club was Ayn Rand, author of The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged.

The Hollywood Studio Club was declared Los Angeles Historic Cultural Monument No. 175 on May 4, 1977.

In 1928, Morgan had a medical procedure that ended badly. She had an inner ear infection, which had plagued her since childhood, so the surgery she selected involved removing the inner ear. During the operation, the ear surgeon accidently severed a facial nerve, which caused Morgan to have speech and facial issues similar to what an individual who has had a stroke experiences. Despite the botched operation, Morgan continued to work and did not blame the surgeon despite having balance, face and speech problems for the rest of her life.

Hollywood Studio Club entrance. The breezeway above the entrance was unfortunately filled in. Author photo.

Hollywood Studio Club. The Hollywood Studio Club encircles this patio. Author photo.

According to the American Institute of Architects Journal, Morgan was a member of the American Institute of Architects (Northern California chapter) beginning in 1921 and was an emeritus member beginning in 1949, though from all accounts she seemed to shun participation in architectural organizations.

Julia Morgan designed more than seven hundred buildings during her career, which lasted until the early 1950s. William Randolph Hearst was the only journalist she spoke to on a regular basis. Morgan did not like to post her name at job sites, avoided publicity and never drew more than $10,000 a year in salary. Morgan’s best-known buildings include Hearst Castle in San Simeon, a Mission Revival–style campanile at Mills College in Oakland, St. John’s Presbyterian Church in Berkeley and the Asilomar Conference Center in Pacific Grove, California.

Julia Morgan never married and died at her home on February 2, 1957. She was eighty-five years old. She is buried at Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland, California.