Chapter 5

The abolitionist renaissance and the coming of the Civil War

Although abolitionists never enjoyed widespread popularity in the United States, they found that northerners were more interested in their critiques of slavery during the 1850s. The passage of a stronger fugitive slave law, which turned white citizens into would-be slave catchers, raised new questions about the slave power and allowed abolitionist arguments to resonate more deeply. The result was an abolitionist renaissance. From politics to pop culture, abolitionist ideas were diffused widely through American society. Even if most northerners did not join antislavery societies, the abolitionist struggle seemed ascendant in ways not seen since the late eighteenth century. And this had profound consequences for sectionalism, disunion, and civil war.

The Fugitive Slave Law and the abolitionist renaissance

The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 inspired among many northerners a newfound sympathy for abolitionism. Part of a compromise that banned the slave trade in the District of Columbia and allowed California to enter the Union as a free state, the law mollified masters by cracking down on the perennial problem of runaways. It allowed federal commissioners to seize suspected fugitives and paid slave catchers a $10 bounty for every recovered runaway. It also empowered commissioners to deputize northerners as slave catchers, threatening fines and prison terms for those failing to comply. Though abolitionists condemned the law for its impact on blacks, whites understood that their liberties were threatened too.

Although masters used the law to recapture hundreds of runaways, many northern communities resisted it. After its passage in September, commissioners arrested James Hamlet in New York City and returned him to bondage in Maryland. Abolitionists raised funds for Hamlet’s freedom, holding a big rally when he returned to New York. “Several thousand people, black and white, attended” the event, the New York Tribune reported, and there was a “strong spirit of resistance” to the “man stealing” law. According to longtime reformer Isaac Hopper, the Hamlet case “excited universal indignation at the vile law” and, for a change, made abolitionists heroes.

Several other cases proved the wisdom of Hopper’s words. In Buffalo, abolitionists challenged officials who captured an alleged fugitive named Daniel in the summer of 1851. Arguing that he was a free man, a large group—led by blacks—gathered at the courthouse and tried to liberate Daniel. After abolitionists filed a writ of habeas corpus, Daniel was released and fled to Canada. In Syracuse, the so-called Jerry Rescue again found local citizens openly defying authorities. The case centered on William Henry, an escaped slave from Kentucky who lived under the alias “Jerry” before being seized by slave catchers in October 1851. Led by blacks, abolitionists stormed the prison and spirited Jerry away to Canada. For the next several years, local abolitionists celebrated Jerry’s liberation day.

In 1860, still another high-profile case occurred in Troy, New York, where officials claimed Charles Nalle was a fugitive slave from Virginia. A throng of activists demanded Nalle’s freedom, including Harriet Tubman, a former slave from Maryland who was already a noted figure on the Underground Railroad. On her way to an antislavery meeting in Boston, she heard about the Nalle case and literally threw her body in the way of slave catchers twice to foil Nalle’s return to bondage. The New York Tribune called it “The Slave Rescue at Troy.”

So disruptive were black and white abolitionists along the Erie Canal corridor that Daniel Webster, the noted Massachusetts congressman, toured New York State with a special message: stop fugitive slave rescues or risk disunion. Even when Webster told a crowd in Syracuse that the city had become nothing but a “laboratory of abolitionism, libel and treason,” local abolitionists refused to back down.

Every year, the Fugitive Slave Law faced major challenges somewhere in the North. In February 1851, Boston abolitionists stormed a prison holding Shadrach Minikins, a recaptured fugitive from Virginia, and sent him to freedom in Montreal. In the summer of 1853, slave catchers grabbed John Freeman in Indianapolis, Indiana, after a St. Louis master named Pleasant Ellington claimed that he was an escaped slave named “Sam.” Remarkably, the federal commissioner allowed an investigation to ensue. While Freeman sat in jail, watched by an armed guard he had to pay for, his legal team produced witnesses showing that he was a free black man from Georgia and that Ellington had knowingly made a false claim. In fact, the real “Sam” had escaped to Canada, where he offered a deposition supporting Freeman’s story.

In 1854, abolitionists liberated Joshua Glover from a Milwaukee jail and helped him escape to Canada. Glover had fled his St. Louis master and resettled in Milwaukee, where a small but active abolitionist community operated. After slave catchers found Glover, local citizens physically intervened on his behalf. Sherman Booth, a local politician and abolitionist, supported—but did not actually participate in—Glover’s liberation, which led to his arrest for violating a federal law. The Wisconsin Supreme Court heard the case and released Booth after proclaiming that the Fugitive Slave Law was unconstitutional—the only state court to do so. While he was retried and briefly spent time in jail, Booth eventually walked away.

Perhaps the most riveting rescue occurred in 1855, when abolitionists freed Jane Johnson and her two children on the Philadelphia waterfront. Johnson had been traveling with her master, North Carolina politician John Wheeler, who was on his way to a diplomatic post in Nicaragua. At a Philadelphia hotel, Johnson informed members of the black underground that she wished to be free. Abolitionists confronted Wheeler the next morning. As Quaker Passmore Williamson stood before Wheeler, black abolitionist William Still spirited Johnson’s family away. Though Williamson spent several months in jail, he became a celebrity. Lucretia Mott, Frederick Douglass, and others visited him. Charges against Williamson were eventually dropped, and Still escaped punishment altogether. Rather stunningly, Johnson herself returned to testify in support of Williamson. She vanished again and was never caught.

Slave masters fumed again in 1858 when Ohio abolitionists foiled another attempted recovery. The Oberlin-Wellington Rescue began when slave-catchers tracked down an alleged Kentucky runaway named John Price in the college town well-known for its activism. Oberlin abolitionists pursued slave catchers to the nearby town of Wellington. Abolitionists eventually stormed the hotel where the slave catchers had barricaded themselves, liberating Price and sending him to Canada. Although federal charges were brought against thirty-seven people, Ohio authorities retaliated by arresting the slave catchers on a charge of kidnapping. After bargaining over their fate, most charges were dropped against Price’s rescuers. Only two men did jail time: Charles Langston, a well-known black abolitionist and member of the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society, and white reformer Simeon Bushell. Langston became a hero, telling the court that the fugitive slave law “outrages every feeling of humanity.” The Cleveland Daily Herald agreed, writing that the “trial of these men for the crime of assisting a fellow man to escape life bondage … is a scene disgraceful to our country.”

In each of these cases, fugitive slave rescues heightened debate over the willingness of northerners to support southern slavery. The most famous case of the decade—the return of Anthony Burns to Virginia bondage—showed that abolitionists gained public support for their antislavery work even when failing to free a fugitive. After he had been recaptured in Boston in May 1854, Burns was held in a local prison, where abolitionists staged a daring but unsuccessful raid to free him. Tragically, a white guard was killed in the melee—something that would normally have become the focus of public attention. But the opposite happened: As Burns was transferred to a ship bound for slave country, thousands of Bostonians lined the streets in protest. As businessman Amos Lawrence famously put it, “we went to bed one night old-fashioned, conservative, compromise Union [men] … and waked up stark mad abolitionists.” Lawrence was not alone in questioning his previously moderate stand on slavery. Many abolitionists who saw themselves as peaceable citizens became militant opponents of the “man-stealing” law. No escaped slave was again recovered in Boston.

A literary renaissance

Fugitive slave conflicts revivified abolitionism. As concern over the law mounted in the North, abolitionists found themselves at the center of debates over civil liberties, the slave power, and the meaning of American democracy itself. For many people, abolitionists were truth-tellers, not rabble-rousers. More Americans than ever wanted to learn about the antislavery cause. Abolitionists met this demand with a flurry of new publications and artistic productions, making the movement relevant to American philosophy, literature, and even music. The Hutchinson Family Singers became one of the most popular vocal groups at midcentury for their heart-rending antislavery songs, including “The Fugitive’s Song” (which was inspired by Douglass’s autobiography).

Others meditated on slavery’s negative environmental and economic consequences. Naturalist Henry David Thoreau became a more visible abolitionist commentator, offering a memorable condemnation of bondage in 1854 when he compared Massachusetts to a deadened landscape in the wake of the Anthony Burns affair. A member of the Concord Anti-Slavery Society, Thoreau linked abolitionism to his ecological views. Seeing all parts of American society as interconnected, he asserted that northerners were just as responsible for the ecology of bondage as southerners. Similarly, New York journalist Frederick Law Olmsted published A Journey Through the Seaboard Slave States (1856), which noted that both investors and immigrants refused to settle in the South because slavery discouraged free labor economics. Though he sometimes employed romantic racialism to make his case (arguing that enslaved people were virtual children who might require oversight in freedom), Olmsted inspired others to think more deeply about slavery’s economic and environmental impacts.

John Trowbridge’s novel Neighbor Jackwood (1856) used fiction to interrogate slavery’s impact on the North. Trowbridge’s tale focused on the plight of a runaway slave named Camille, who is protected by the Jackwood family after arriving in New England. As Trowbridge later explained, Neighbor Jackwood was based on the Anthony Burns imbroglio, which electrified everyone around him. The book went through several printings and was even made into a play.

Of course, no book was more impactful than Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Originally serialized in an abolitionist newspaper The National Era, the book sold well over one million copies after it was published in 1852. The novel spawned board games, trading cards, and plays, and Stowe went on an international speaking tour.

What made the book so popular and powerful? Stowe used collective biography to “enlist the sympathies” of the world in the antislavery cause, as she put it in a letter to Britain’s Queen Victoria. The book’s title character, a pious enslaved man named Tom, suffers at the hands of a heartless master—Simon Legree—who eventually kills him for the sin of believing that his Christian soul was equal to that of any white person. Even the prospect of death cannot vanquish Tom’s spirit, which makes him the Christ-like sacrifice for the American sin of slaveholding—a Christian-centered theme well suited to nineteenth-century revivalists. Stowe made other characters pay for slavery’s evil too, including Eva, an idealized child of a slaveholding family who buys Uncle Tom before having to sell him to pay debts. Eva, seemingly innocent of sin, is the only white character who seeks Tom’s freedom. Stricken by disease, she passes away, leaving everyone devastated. Stowe’s message: Slavery killed Eva just as it would destroy the American soul.

Despite its popularity, Stowe’s novel did not appeal to everyone. No character in the book spoke for immediate abolition, frustrating some hard-core abolitionists. Moreover, the book used unflattering images of African American characters—including Uncle Tom, who always deferred to white power, and Topsy, an enslaved child whose wild behavior seemed inherent in her blackness. Stowe also flirted with colonization in yet-another storyline: the tale of George and Eliza Harris who escape slavery by fleeing to freedom in Canada. They then settle in the American Colonization Society’s former colony of Liberia. Was this truly an abolitionist ending?

These concerns notwithstanding, Stowe’s book remained a powerful indictment of slavery. As Stowe revealed in a follow-up book, The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (“facts for the people”), her novel was based on runaway slave ads, slave narratives, and stories of fugitive slave renditions. Having lived in the antislavery borderland of Cincinnati before settling in Boston, Stowe often heard about slave escapes. The daughter of a minister who married a preacher, she offered a literary sermon on bondage designed to shock, sadden, enrage, and ultimately galvanize Americans into becoming an antislavery congregation.

Though some ardent reformers believed she was not hard enough on slaveholders, the outcry from southern masters only deepened Stowe’s abolitionist credentials. Slaveholder George Frederick Holmes offered a scathing review in The Southern Literary Messenger, blasting Uncle Tom’s Cabin as “professedly a fiction.” Stowe, he sneered, was a “politician in petticoats” whose novel lied about slavery and deserved nothing but derision. Holmes’s review drew more attention to Stowe’s book. As slaveholders now realized, they could not gag slavery debate in American culture.

Black abolitionist renaissance

Though abolitionists were gratified to see white northerners fight the slave power, the Fugitive Slave Law prompted the exodus of between ten and twenty thousand African Americans, mostly to British Canada. While they lived in vibrant “ex-pat” communities in Toronto, Hamilton, and other cities, blacks still found ways to attack American slavery. Mary Ann Shadd Cary, who hailed from a well-known black abolitionist family in Delaware, touted immigration to Canada as a boon to oppressed African Americans. As Cary put it in an 1852 pamphlet, “the inquisitorial inhumanity” of the Fugitive Slave Law proved that the United States was inhospitable to black freedom. In Canada, however, whites had an “innate hatred of American slavery” and free blacks had suffrage rights, access to public education facilities, and legal protections.

Cary joined forces with a talented editor who had once been enslaved in Maryland: Samuel Ringgold Ward. After living in New York, Ward moved north and joined the Canadian Antislavery Society. He and Cary published The Provincial Freeman, which reported on black abolitionist initiatives across the Atlantic world. When Ward traveled, Cary assumed the main editorial duties.

A superb writer and editor, she began printing letters fromblack abolitionist William Still, who became the leader of the Underground Railroad in Philadelphia. Still told readers that no law would stop fugitives from escaping American slavery and perhaps going to Canada. For that reason, Still reported, The Provincial Freeman “is read [in Philadelphia] with lively interest.”

Both Cary and Still knew that Canadian exodus was part of a broader debate among black abolitionists at midcentury: was racial justice possible in slaveholding America? Martin Delany, a free black activist from western Virginia, scoffed at the notion. Espousing an early version of black nationalism, Delany convened the first black emigration convention in Cleveland in 1854 to encourage black exodus. As he observed in The Political Destinyof the Colored People (1852), throughout history oppressed communities achieved freedom and justice only by creating new settlements where they controlled economic, political, and social affairs. To achieve such results, blacks in America must build their own nation.

Despite Delany’s forceful arguments, many African Americans rejected mass migration. Black abolitionists argued that they must remain allies to enslaved people struggling for freedom in the South and help overturn the broader system of racial oppression stifling northern society. Like revolutionary leader James Forten, they saw African Americans as a redeeming people who would transform the nation’s moral fabric through waves of prophetic activism. Civil rights were American rights and African Americans had equal claims to them.

Frederick Douglass became the great exemplar of this civil rights position. He supported local struggles to integrate Rochester schools and used his various newspapers to battle the slave power. While he also supported workingmen’s rights and women’s equality (he attended the Seneca Falls convention in 1848), Douglass focused on a dual reconstruction of American society: slaying southern bondage and ending northern racism. He could do that only by remaining in the United States.

Douglass was not afraid to level harsh critiques of white abolitionists, from Garrison to Harriet Beecher Stowe. In his most famous speech, “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” (1852), Douglass told a largely white crowd in Rochester that America had reached a crisis point. With both the Fugitive Slave Law and the domestic slave trade imperiling black lives, Douglass wondered why African Americans would ever celebrate July 4th. “Are the great principles of political freedom … extended to us?” he asked. The answer was clearly no. And so, he announced, “you may rejoice, I must mourn” on Independence Day. The speech condemned not only bondage but also white allies who did not match the activist convictions of the founders they celebrated. In an inspiring peroration, Douglass reminded abolitionists that the American Revolution was the result of action, not simply words.

In a less well-known but equally rousing speech a year later, Douglass returned to the Declaration of Independence as the touchstone of American equality. Reporting from a national convention of black activists in Rochester, Douglass told white Americans that we “address you as American citizens asserting their rights on their own native soil.” “We are Americans,” he concluded, and we demand nothing less than full civic equality. Until that time, he and black reformers vowed never to “repress the spirit of liberty within us, or … conceal … our sense of the justice and dignity of our cause.”

Across the North, black abolitionists took up the civil rights standard by challenging school segregation, segregated accommodations, and racist thinking. In Philadelphia, African Americans began challenging segregated streetcars, while in Boston black activists sued to integrate city schools (in the case of Roberts v. Boston). In Ohio, John Mercer Langston became the first black lawyer to pass the state bar exam, joining his brother Charles in a variety of antiracist struggles. Again and again, black abolitionists reminded Americans that the struggle for racial justice was national in scope and one dedicated to the idea that the United States was, in essence, an abolitionist nation.

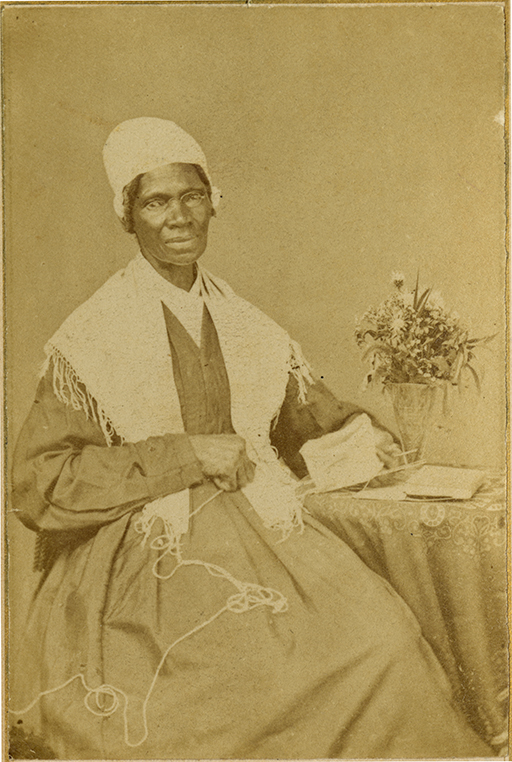

9. Like Douglass, Sojourner Truth saw photography as a truth-telling medium that would reveal the essential humanity of African Americans. In this Civil War image, Truth uses a piece of yarn to depict the United States on her lap. The implication is clear: black bodies will determine the fate of the nation. Truth herself filed for the copyright of this photograph.

To make their case, black abolitionists embraced innovative visual technologies. For instance, both Douglass and Sojourner Truth utilized the new medium of photography to bolster black freedom claims. A photo did not lie, Douglass believed, and he linked the struggle for justice to what he called the “Age of Pictures.” Little wonder that Douglass became one of the most photographed Americans of the nineteenth century: he wanted the objective lens of the camera to show the inescapable humanity of African Americans. Similarly, Sojourner Truth used photos to tell prophetic stories about herself and the nation. In one of her most famous photos, Truth sits in a chair with a piece of yarn draped over her lap in the form of the United States. While she poses as a respectable middle-class figure, the map implies that black bodies will not rest easily until slavery had been vanquished from the land. It was a stunning photograph, and it spoke volumes about the dynamic activism of black abolitionists before the Civil War.

Abolitionist politics and the abolitionist constitution

The rising visibility of black and white abolitionists made a mark on slaveholders. That became clear in November 1850, when a convention of southern leaders meeting in Nashville issued a series of resolutions warning northerners to control those “aggressive” abolitionists. Throughout the 1850s, “fire-eaters,” a radical subset of proslavery politicians, threatened disunion as a way to push back.

Though their movement had grown, abolitionists remained on the periphery of political power. Just how would they destroy slavery? Like all movements for social change, they struggled to convert social discontent into coherent political action. One wing of the abolitionist movement still eschewed politics, touting disunion and radical individualism as a better way to overcome the slave power. John Jacobs, a fugitive slave and brother of slave narrator Harriet Jacobs, favored disunion because he thought it would force northerners to choose between slavery and freedom. Boston minister Theodore Parker supported ever-more-radical challenges to the Fugitive Slave Law. Parker told his congregation that he would “defend the fugitive with all my humble means and power,” including physical force. Citing higher law principles—or the idea that there was a divine law above corrupt political authority—he asserted that a fugitive slave had “the same natural right to defend himself against the slave catcher” as anyone. “The man who attacks me to reduce me to slavery,” he argued in the voice of the fugitive, “in that moment of attack alienates his right to life.”

Unconvinced by such confrontational stands, Connecticut abolitionist Elihu Burritt proposed a new buyout plan of American bondage. Forming the National Compensation Emancipation Society (NCES) in 1857, he asked the federal government to pay slaveholders $250 for each liberated slave (with additional sums provided by the states) and $25 to each enslaved person (which they could use to settle domestically or migrate internationally). Though well under the going price for enslaved people, NCES advocates hoped that masters would see the “brotherly spirit” behind compensated emancipation and support the cause.

Building on earlier forays into politics, a succession of midcentury abolitionists also sought to deploy the U.S. Constitution against slavery. Inventor and lawyer Lysander Spooner argued that the federal government could not protect bondage because the Constitution did not use the term “slave” (the constitutional phraseology was “persons held to labor”). Spooner also believed that enslaved people could use writs of habeas corpus to challenge their detainment in bondage. Like Absalom Jones in 1799, Spooner believed that the Constitution supported black liberty over slaveholders.

By the 1850s many more reformers supported this position. William Goodell published a steady stream of books and pamphlets supporting an abolitionist Constitution. As he put it, “[i]f the Constitution requires us to support slavery, then the Constitution requires us to overthrow our own liberties, to declare war against universal humanity, to rebel against God, and incur his displeasure.” But “if the Constitution be in favor of liberty and against slavery, then it is our duty and interest to wield it for the overthrow of slavery and the redemption of our country from the heel of the slave power.” From his ministerial base outside Rochester, Goodell became an increasingly respected abolitionist theorist.

Indeed, Goodell’s ideas pointed toward the “Freedom National” doctrine. Espoused by Massachusetts politician Charles Sumner, the doctrine viewed freedom as a national principle and slavery as a local one. As Sumner put it in his famous 1852 speech, “Freedom National, Slavery Sectional,” “the Constitution was ordained, not to establish, secure, or sanction Slavery—not to promote the special interests of slaveholders—not to make Slavery national, in any way, form, or manner; but to ‘establish justice,’ ‘promote the general welfare,’ and ‘secure the blessings of Liberty.’ Here [in America] surely Liberty is national.”

By interpreting the Constitution as a freedom document, Sumner, Goodell, and Spooner brought abolitionism into the American mainstream. Whereas for decades abolitionists had defined themselves as outsiders who challenged a corrupt political and constitutional order, midcentury reformers saw themselves as insiders who redeemed core American institutions. Hoping to correct “a popular belief” that slaveholders had eternal rights, Sumner excoriated anyone who argued that slavery was “a national institution.” Wrong, he charged. Slavery was “a sectional institution … with which the nation has nothing to do.” This policy of federal neglect would surely kill bondage.

Even Douglass repudiated his former Garrisonian beliefs and joined reformers who read the Constitution’s preamble—“to establish justice” and “secure the blessing of liberty” for all Americans—as an abolitionist standard. Unsurprisingly, Douglass converted to political abolitionism too. Believing that abolitionists must use the political process to coerce slaveholders institutionally, he supported a range of third parties, including the Liberty Party. Douglass also helped launch the Radical Abolition Party (RAP), which called slavery unconstitutional, supported full citizenship for African Americans, and offered a stunning vision of interracial leadership by selecting black activist James McCune Smith as its inaugural convention chairman—something that would not happen again in party politics until the 20th century.

Though it gained little support, the Radical Abolition Party illuminated abolitionism’s organizational dynamism. Far from a small band of New England radicals piously philosophizing about moral perfection, abolitionism was constantly experimenting with new political and social doctrines. As Goodell put it in Slavery and Antislavery (1852), there was “moral suasion” abolition, “political abolitionism,” church-oriented abolition, and so on. And now that abolitionists were pushing into politics, slaveholders would find themselves pressed on more and more fronts.

The rise of the Republican Party

As abolitionists explored constitutional arguments against slavery and experimented with political parties, a new generation of antislavery statesmen entered the federal government: New Hampshire’s John P. Hale, Indiana’s George Julian, Ohio’s Benjamin Wade and Samuel Chase, and New York’s William Seward. Bolstered by northern discontent with the Fugitive Slave Law, they supported restrictions on slavery in the West and opposed the slave power. Many of these statesmen also spoke of black freedom as a constituent part of America’s past and future, making clear to slaveholders that they saw the union in ways that were fundamentally different from theirs.

Territorial debates over bondage pushed more northerners into the antislavery fold and emboldened antislavery statesmen. Though the issue had periodically roiled Congress, slavery’s status in the West became a hot-button issue after the Mexican War ended in 1848. Abolitionists mobilized against the introduction of slaves in any conquered territory—a point politicians picked up. When Pennsylvania Democrat David Wilmot—no friend of abolitionists—proposed a law prohibiting slavery in new territories, slaveholders argued that bondage must be allowed to expand, or it would die. The Wilmot Proviso failed to pass but it put southern politicians on notice. After California entered the Union as a free state in 1850, Deep South politicians vowed not to lose another territorial battle.

Southern masters and their northern allies vindicated that vow with the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Introduced in 1854 by Illinois senator Stephen A. Douglas, a Democrat who courted southern support for a transcontinental railroad, the law repealed the Missouri Compromise and opened the Great Plains to slavery via the concept of popular sovereignty. No longer would slavery be prohibited above the 36˚30ˈ parallel; rather, a territory’s population would decide slavery’s fate. The act angered a broad swath of northerners. Stoked by abolitionists, northerners staged town hall meetings, lecture campaigns, fundraisers, and petition drives to oppose the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Abolitionists also sponsored free soil settlers who confronted slaveholders in territorial Kansas. The New England Emigrant Aid Society (NEEAS), a joint stock company dedicated to building a free Kansas, helped populate abolitionist-friendly towns such as Lawrence.

Free soil settlers included Daniel and Merritt Anthony of Rochester. Brothers of Susan B. Anthony, who soon became a lecturer for the American Anti-Slavery Society, they had been abolitionists since the 1840s and counted Frederick Douglass as a friend. On their way to Kansas, Merritt recalled hearing one man threaten to tar and feather abolitionists. Undeterred, he and his brother settled in the embattled territory. Sending news of Kansas outrages back to the East, the Anthony brothers offered a vital connection to slavery debates out in the West.

The Anthony brothers were right to worry about their safety in Kansas. Abolitionists were not only verbally threatened but physically assaulted. In May 1856, the abolitionist stronghold of Lawrence was razed by a proslavery mob of roughly eight hundred people. In addition, “Border Ruffians” from Missouri consistently disrupted free state politics in Kansas. Abolitionist partisans in New York City sent “Beecher Bibles” to western emigrants: boxes of rifles named in honor of abolitionist minister Henry Ward Beecher. But that did little to quiet fears.

Kansas became a great recruiting tool for a new political party dedicated to fighting slavery’s territorial expansion: the Republican Party. Formed in 1854, Republicans not only opposed slavery’s westward expansion but also vowed to make American liberty the core of party identity—something that appealed to black as well as white reformers. The Republican Party platform of 1856 used the Declaration of Independence, with its guarantee of liberty as an American birthright, as the party standard. Moreover, Republicans promised to secure the liberty of conscience and press for embattled northerners—code words designed to appeal to potential abolitionist voters who felt that the Fugitive Slave Law had marginalized them. Republicans also supported free labor regimes, educational uplift, and the development of transportation infrastructure in the West.

The Republican Party replaced the Free Soil Party as the great hope of political abolitionists. Launched with great fanfare in 1848, the Free Soil Party focused on one major goal: restricting slavery’s western growth. By stripping abolitionist planks from the old Liberty Party agenda, including emancipation in the District of Columbia, free soilers hoped to appeal to a much wider group of northerners. While it tallied 250,000 votes in the presidential election of 1848, the Free Soil Party created a rift among abolitionists. The party ran Martin Van Buren, slaveholder Andrew Jackson’s confidant, as president. More broadly, many partisans of the Free Soil Party envisioned the West as a haven for white workers, not black settlers. When some settlers proposed a constitution prohibiting African Americans from living in the future state of Kansas, hard-core abolitionists registered alarm. Perhaps Garrison was right: popular politics and abolition did not mix.

Despite such concerns, perceptive reformers saw the Free Soil Party as a symbol of shifting allegiances in the North. Frederick Douglass, who attended the inaugural Free Soil convention in Buffalo, viewed it as a way station for voters frustrated by the slave power’s influence on the two main political parties—Democrats and Whigs—yet still not ready to embrace emancipation. Douglass made an important point: members of the Free Soil Party were not monolithic. The party included politicians like Charles Sumner, who argued that limiting slavery’s growth was a major step toward national freedom, and Samuel Chase, who defended fugitive slaves in Ohio.

Yet the Free Soil Party ultimately failed to keep pace with northern anger at the slave power. After a lackluster performance in the election of 1852, the party faded. Though it did not favor immediate emancipation in the South, the Republican Party was better able to capture northern frustration. While ardent abolitionists refused to support the Republican Party, moderates understood that northern opposition to the slave power was at an all-time high and they would be foolish to simply ignore Republican prospects. In 1854, anti-Kansas politicians captured dozens of seats in Congress. By tapping into northern resentment of the slave power, Republicans captured their first major political victory in 1856 when Massachusetts abolitionist Nathanial Banks was elected Speaker of the House. In the presidential election later that year, Republicans secured over more than one million votes (33 percent of ballots cast) and 114 electoral ballots. The party was a political juggernaut.

Though wary of Republicans, Frederick Douglass hoped for Republican “success.” While dismayed that Republicans often rallied around the standard of “No more Slave States” rather “Death to Slavery,” he knew that white northerners “will [still] not have [an abolitionist party] … and [so] we are compelled to work and wait for a brighter day, when the masses shall be educated up to a higher standard of human rights and political morality.” The Republican Party was a step forward for the antislavery cause.

In fact, abolitionists found themselves on the same page as Republicans on several key occasions. In May 1856, Charles Sumner was viciously attacked in Congress after he gave a stunning speech accusing slaveholders of raping the “virgin” soil of Kansas. That prompted South Carolinian Preston Brooks to whip Sumner from behind with a cane. Trapped in his Senate desk and surrounded by southern politicians who would not let others intervene, Sumner was nearly beaten to death.

Brooks’s attack on Sumner underscored a key abolitionist talking point: slaveholders acted as despots. Sumner was not simply an abolitionist martyr but a virtual white slave whose brutal whipping illustrated what bondsmen and women endured every day. Black abolitionists rushed to Sumner’s defense. In Boston, African Americans gathered at escaped slave Leonard Grimes’s church to condemn slaveholders for their “brutal, cowardly and murderous assault … upon our distinguished Senator, Charles Sumner.” The caning of Sumner raised the visibility and respectability of both abolitionists and the Republican Party.

The Supreme Court’s Dred Scott v. Sandford decision in March 1857 created another bond between Republicans and abolitionists. In ruling against Dred Scott, an enslaved man who sued for his freedom after being taken into the Midwest, the Supreme Court hoped to quash slavery debate across the country and solidify slaveholders’ rights nationally. Writing for the majority, Roger Taney (a Maryland slaveholder) dismissed Scott’s freedom claim on two grounds: first, slaveholders’ property rights were sacrosanct everywhere in American society, including free territories and states; and, second, African Americans were not U.S. citizens and, as he put it, had “no rights that a white man was bound to respect whatsoever.”

Both abolitionists and Republicans responded vigorously to the Dred Scott decision, helping shape a sense of shared political destiny. Douglass railed against the opinion in speeches and editorials. “The testimony of the church, and the testimony of the founders of this Republic, from the Declaration downward, prove Judge Taney false,” he told a New York City crowd in May. Though Garrison saw the decision as additional proof that American governance had been defiled by the slave power, he too was outraged by Taney’s rhetoric.

Among Republicans, Abraham Lincoln took the lead in criticizing Taney’s ruling. Like Douglass, he saw Dred Scott through the lens of history. “I had thought the Declaration contemplated the progressive improvement in the condition of all men everywhere,” Lincoln commented, but the Taney decision reduced it to a mere political maneuver to support American independence. For Lincoln, as for Douglass, the Declaration remained the ultimate touchstone of American rights and values. The Dred Scott case violated that notion. Channeling Douglass, Lincoln even asked one audience about to celebrate the Fourth of July, “what for?” “But I suppose you will celebrate; and will even go so far as to read the Declaration,” he continued. “Suppose after you read it once in the old fashioned way, [then] you read it once more with Judge Douglas’ version,” which focused on slaveholders’ property rights and not human rights. How would it sound then? Clearly, Lincoln read Douglass’s famous speech, agreeing that Taney’s decision made July 4th a day to mourn and not celebrate.

When Lincoln asserted that “the negro is a man, that his bondage is cruelly wrong, and that the field of his oppression ought not to be enlarged,” he won more friends among abolitionists. For Douglass, Garrison, and a range of others, the Republican Party seemed to be doing, at least in part, what they had done for decades: speaking truth to the slave power.

And that made the election of 1860 a truly historic event. It would be the first presidential election in which abolitionist values—if not policies—would become a key part of the nation’s future.