Chapter 6

American emancipations: Abolitionism in the Civil War era

Even before the election of 1860, abolition made national headlines with John Brown’s failed raid at Harpers Ferry. Though he hoped to foment a slave rebellion in western Virginia, Brown’s raid ended with his capture and execution. While many Americans saw him as a fanatic, abolitionists viewed Brown as a flawed but conscience-driven man who rang an alarm bell about bondage. Like generations of slave rebels, Brown saw slavery as a perpetual war against enslaved people—a war that commanded rebels and their allies to fight back. Though still no fan of violence, Garrison told a Boston audience that “[w]e have been warmly sympathizing with John Brown all the way” to his death. He told abolitionists to use Brown’s memory to do “the work of abolishing slavery.”

Ironically, Brown’s death put a spotlight on slaveholders too. While southern masters and their northern allies vilified abolitionists, some Republicans joined abolitionists in using Brown’s memory to focus on slave power outrages. No one could have predicted that this tactic would lead to a civil war, or slavery’s complete destruction, in the next few years. Then again, abolitionism had often taken unpredictable turns. The key point is that abolitionists were ready to exploit events to their advantage.

John Brown: abolitionist

Before he became a martyr, John Brown was an abolitionist Zelig: he was everywhere. Brown met with fugitive slaves in Canada, Free Soil settlers in Kansas, and abolitionist leaders in New York, New England, and Ohio. An old-style Puritan, Brown also believed in a modern brand of interracial equality. In May 1858, he and a large group of black expatriates gathered in Chatham, Ontario (British Canada), to draft a new government for a post-slavery America. This “Provisional Constitution” called U.S. bondage “a most barbarous, unprovoked, and unjustifiable war of one portion of its citizens upon another portion.” The only remedy was immediate abolition and the creation of an interracial republic where blacks could be congressmen, presidents, and equal citizens. Brown carried the Provisional Constitution with him to Harper’s Ferry.

Though he aided fugitive slaves in the Northeast, Brown’s belief in physical confrontation with slaveholders took shape in the West. Settling in Kansas with his sons, Brown found free soilers outnumbered and outgunned. Chagrined at physical attacks on abolitionists dating back to Elijah Lovejoy, he vowed to fight back. In May 1856, after proslavery forces destroyed Lawrence, he led a group of vigilantes, who killed five men in retaliation. Known as the Pottawattamie Massacre, the event shocked the nation. But Brown was not publicly identified and headed back to the East.

By 1859, he saw slave rebellion as the only pathway to national emancipation. Brown informed a small circle of abolitionist leaders of his plan to attack a federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, and then head into the Appalachian Mountains, where his forces could make periodic attacks on southern plantations. After gathering an interracial group of twenty-one activists on a Maryland farm, Brown struck at Harpers Ferry on October 16. Though Brown’s men briefly occupied the armory and took hostages from a nearby plantation, they soon retreated to a firehouse after being surrounded by local militia. Eventually, U.S. Army colonel Robert E. Lee captured Brown and several surviving raiders. On December 2, Brown faced the gallows.

While Lee and many slaveholders called him a “madman,” many abolitionists hailed Brown as a prophet. “Who believes he is crazy now?” Henry David Thoreau asked in 1860, when slaveholders threatened to secede from the Union to protect slavery. The Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society formally saluted Brown as a freedom fighter. In New York City, James McCune Smith hailed Brown as a hero.

Abolition, secession, and war

In the wake of Brown’s raid, abolitionists found allies among Radical Republicans. Illinois Senator Lyman Trumbull subverted a Virginia congressman’s investigation into Brown’s raid by adding that a federal committee should also examine slaveholding outrages in Kansas. Ohio Republican Benjamin Wade agreed. While neither Wade nor Trumbull supported Brown’s violent tactics, they depicted slaveholders (not abolitionists) as disturbers of the nation’s peace. The abolitionist-Republican alliance, though tenuous, ensured that neither slavery nor slaveholders would escape scrutiny. This development worried southern masters.

Abraham Lincoln certainly believed that a lesson was to be learned in “old John Brown.” Like other Republicans, he distanced himself from Brown’s violent means while also sympathizing with his abolitionist ends. When Democrats blamed Brown’s raid on the Republican Party, Lincoln countered that slave rebellions predated his party’s formation. As he noted in his Cooper Union address, which launched Lincoln’s presidential bid, the American founders wanted to put slavery on the path to elimination. He added that with no more slave states in the West, there could be no slave rebellions there.

Lincoln offered just enough antislavery substance to gain abolitionists’ tentative support. “So far as the North is concerned,” Garrison observed just before the 1860 presidential election, “a marvelous change for the better has taken place in public sentiment in relation to the anti-slavery movement,” with most Americans acknowledging the essential “conflict between free institutions and slave institutions.”

Lincoln’s victory in November 1860 constituted a watershed in American politics. Securing a plurality of votes, he became the first presidential candidate to win on an avowedly antislavery platform. Though Republicans conceded bondage’s legality in the South, they called expansion of slavery “political heresy,” and they vowed to keep slavery out of new territories. In addition, the Republican Party platform conjured images of abolitionist founders: men who declared that “the normal condition of all the territory of the United States is freedom.” Finally, highlighting antislavery readings of both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, the platform called egalitarianism the nation’s enduring creed. Unsurprisingly, Lincoln was not allowed on the ballot in ten southern states.

Nevertheless, secession changed the political calculus for Lincoln, who pushed abolition aside to save the hallowed American union. By Lincoln’s inauguration in March 1861, seven Deep South states had seceded and the allegiance of border states (which Lincoln needed) hung in the balance. Tellingly, every Deep South state defended secession by complaining about either fugitive slaves or abolitionist agitation—or both. Georgia secessionists noted that in “the last ten years we have had numerous and serious causes of complaint against our non-slave-holding confederate States with reference to the subject of African slavery.” Mississippi proclaimed that “[o]ur position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery, the greatest material interest of the world” and one now threatened by abolitionist “hostility” in Washington. South Carolina chastised the North for its wanton disregard of the Fugitive Slave Law. “For twenty-five years this [abolitionist] agitation has been steadily increasing,” the state’s secessionists declared, “until it has now secured to its aid the power of the … [federal] Government.” Only disunion would save slavery forever.

To avert disunion, Lincoln vowed to enforce the Fugitive Slave Law and sign a proposed Thirteenth Amendment protecting southern slavery in perpetuity. While Congress never passed the amendment, it illustrated the great odds abolitionists faced in 1861. Those odds grew greater after four more states—led by Virginia—joined the Confederacy in the wake of South Carolina’s firing on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, and Lincoln’s call for military mobilization.

The “secession winter” was one of the most dangerous times for abolitionists, who found angry northerners blaming them for disunion. Susan B. Anthony traveled across New York State vowing “No Union with Slaveholders” and “No Compromise” on slavery. She faced taunts and physical threats but she kept going. “Here we are … alive after the Buffalo mob,” she wrote after one close call. Despite opposition, “we must face it through” and fight for freedom.

The first emancipation: runaway slaves and black Republicans

Anthony’s words served as a keynote to abolitionists’ approach to the Civil War. From 1861 onward, they tried to turn sectional conflict into a grand emancipation struggle. Runaway slaves struck the first abolitionist blow by using secessionist chaos to flee to federal forts, where they could gain their freedom from “black Republicans.” Since Kansas, proslavery politicians had derisively used that term to link Republicans to mass emancipation and interracial citizenship. With Lincoln’s election, disunionists again stirred support for their cause by claiming that “black Republicans” would speedily liberate southern slaves. As Garrison noted, slaveholders “rave just as fiercely as though [Lincoln] were another John Brown, armed for Southern invasion and universal emancipation!”

Enslaved people took masters at their word and headed for “black Republicans.” Even before military battles ensued, fugitive slaves fled to federal forts. In May, three enslaved people—Frank Baker, Shepard Mallory, and James Townsend—requested sanctuary at Fort Monroe, located outside Hampton, Virginia. The commander, General Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts, ingeniously declared them “contraband of war”: illegal property used by slaveholders to fight the Union. Though a Democrat initially wary of emancipation, Butler’s decree flowed from years of abolitionist legal maneuvering. When Colonel Mallory tried to reclaim the runaways, Butler held firm: runaway slaves would not be returned to the Confederacy. The Lincoln administration agreed. The first emancipation proclamation of the Civil War began with runaway slaves.

Abolitionists hailed Butler as a liberator. As the Christian Recorder, a leading African American journal that circulated through many black communities, explained, Butler was like Moses to enslaved people. While Butler’s decree remained limited—enslaved people were in a liminal status between bondage and freedom—it made Union lines a new antislavery borderland. Just as Pennsylvania’s gradual abolition act had unwittingly encouraged a wave of runaway activity on slavery’s northern borderland, so too did Butler’s contraband policy make Union installations a potential freedom line for enslaved people. By summer’s end, nearly a thousand runaways resided at Fort Monroe. Fugitive slaves streamed to Union lines in New Orleans, Kentucky, South Carolina, and many other locales.

They inspired congressional passage of the First ConfiscationAct in August 1861, which allowed military officials to seize contraband property employed against the Union. That law paved the way for a Second Confiscation Act in July 1862 authorizing federal officials to both seize Confederate property andliberate enslaved people in any disloyal area. Even before the Emancipation Proclamation, Confederates condemned these acts as attacks on slavery.

Lincoln worried that confiscation policies would undermine Union support in the loyal border states of Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri, and Delaware. Indeed, at the start of the war, Lincoln was anything but a great emancipator. In August 1861, he reversed General John C. Fremont’s declaration that all slaves of rebel masters in Missouri were free. In the spring of 1862, he overturned Union general David Hunter’s emancipation proclamation in the heart of the Confederacy, which would have liberated more than one million enslaved people in Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina. Abolitionists were infuriated by Lincoln’s timidity.

These political setbacks notwithstanding, enslaved people kept arriving at Union lines. By the war’s end, perhaps a half million enslaved people had fled southern plantations, creating a two- front war for southern masters: one against the Union, another against fugitive slaves.

The thrilling case of Robert Smalls symbolized enslaved people’s ongoing efforts to have an impact on the war. In the spring of 1862, Smalls led his family out of bondage in Charleston Harbor by posing as a sea captain. He seized a Confederate ship, The Planter, and fooled the harbor patrol into letting him pass through. Narrowly escaping a barrage of shells, Smalls delivered the boat to stunned Union forces in the Atlantic. Coming at a challenging time for the Union army, Small’s story recharged the northern war effort.

If the Civil War had somehow ended in 1862, its abolitionist heroes would have most certainly included Smalls and probably not Lincoln. Knowing that war did not automatically mean emancipation, abolitionists vowed to redouble their efforts.

The wartime abolitionist push

While enslaved people pushed from below, abolitionists used the press, pulpit, and lecture halls to call for emancipation in the public sphere. In May 1861, Frederick Douglass wrote that the simplest way to end the war “was to strike down slavery itself.” If “freedom to the slave” was proclaimed “from the nation’s capital,” then the slaveholders’ rebellion would die. Abolitionists heeded Douglass’s call by meeting with Lincoln, petitioning Congress, and staging August 1st commemorations to remind Americans that Great Britain remained the world’s most important abolitionist nation.

For much of the war, abolitionists posed as a loyal political opposition that supported the Union but agitated for slavery’s destruction—including military emancipation. This represented a profound strategic shift in the movement and not all abolitionists supported it. Some radical reformers argued that emancipation must come through moral and not military means; others saw Lincoln as untrustworthy. But most abolitionists agreed that the movement must exploit this crucial moment in history: a civil war that might result in an emancipation peace.

To shape the Union effort, abolitionists became policy experts on the constitutional, legal, and international rationales for wartime emancipation. For instance, Boston abolitionist Mary Booth sought to influence Lincoln by translating Augustin Cochin’s study of French emancipation into English. Booth believed that Cochin’s text was timely, for the French abolitionist argued that Americans must abolish slavery for the good of Atlantic society.

Other abolitionists made intricate constitutional and political arguments for wartime emancipation. Moncur Conway’s The Golden Hour detailed myriad routes to wartime abolition. Like others, Conway agreed with John Quincy Adams that the president, as “commander in chief” of the military during wartime, could abolish slavery to save the nation. In a remarkable passage, Conway asked readers to suppose that Lincoln had issued the following “proclamation” after the first “bomb … fell into Fort Sumter”: “it is hereby declared that all the slaves in this country are free, and they are hereby justified in whatever measuresthey may find necessary to maintain their freedom.” Failing presidential action, Conway noted, Congress had the power to “declare slavery abolished” through “the common defense and general welfare” clauses. Congress could even “impeach the president, if, to the detriment of the Republic, he should refuse” to abolish slavery under the War Powers clause. Moreover, military commanders could issue emancipation edicts to defeat the Confederacy. “In war, slavery is the strength of the South,” Conway commented, and the federal government must attack it at every level.

In April 1862, Radical Republicans in Congress did just this by securing an emancipation law in the District of Columbia. One of abolitionists’ long-standing policy goals, District emancipation earmarked $1 million in federal funds to liberate 3,150 enslaved people. District masters would be paid roughly $300 per emancipated slave while liberated blacks could get up to $100 if they departed the United States. Despite compensation, masters complained that District abolition was arbitrary because they did not get to vote on it.

Lincoln, emancipation, and abolitionism

Abolitionists rejoiced when Lincoln finally embraced emancipation. In July 1862, a desperate Lincoln told his cabinet, which included abolitionists Samuel Chase and William Seward, about plans to issue an emancipation edict as a wartime necessity. Importantly, no one tried to talk him out of it. After Union forces repelled General Robert Lee’s forces at Antietam, Lincoln issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22. It stated that if Confederate forces did not surrender by the end of the year, the Union would declare enslaved people in rebellious territories “forever free.” When Confederates did not comply, the final Emancipation Proclamation took effect on January 1, 1863. Clearly, Lincoln acted for practical as well as moral reasons. As the Union death toll rose, so too did complaints on the home front. In the midterm elections of 1862, anti-war Democrats would gain a significant number of seats in Congress. Lincoln knew he had to do something different.

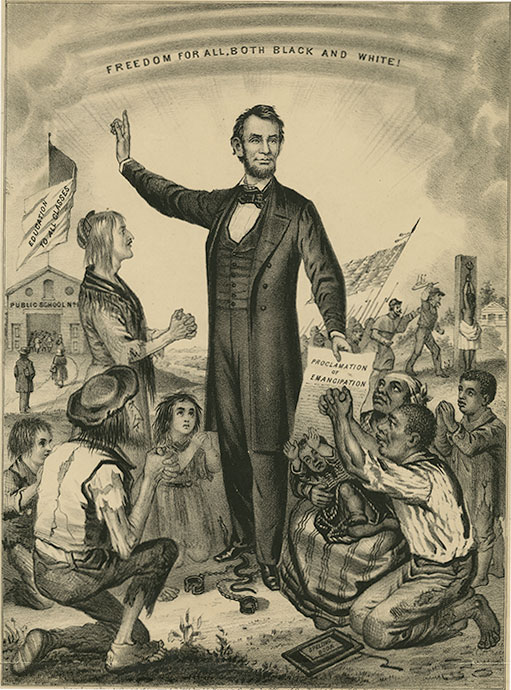

10. As this image shows, some people believed that Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation liberated both enslaved people and white northerners from the tyranny of masters’ rule.

While he came late to wartime abolitionism, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation illustrated his capacity to grow as a president—something abolitionists had hoped would occur. Italso showed Lincoln’s antislavery core: once he issued the Emancipation Proclamation, he did not rescind it. Henry Highland Garnet, who nearly gave up on the United States, hailed Lincoln’s action as one of the greatest events in history. Even the radical abolitionist Parker Pillsbury, who constantly challenged Lincoln, supported the Emancipation Proclamation.

Lincoln’s proclamation had major policy significance. It prevented foreign powers, namely Great Britain, France, and Russia, from recognizing the Confederacy, which was an avowed slaveholders’ republic. At a practical level, the Emancipation Proclamation formalized Union protection of escaped slaves. Although rebellious slaveholders argued that Lincoln had no jurisdiction over them, they understood that his edict encouraged enslaved people to flee to Union lines. Masters took brutal steps to prevent this from happening. Jefferson Davis called the Emancipation Proclamation the “most execrable measure recorded in the history of guilty man.”

In short, the Emancipation Proclamation was a bold move. It marked the first time any U.S. president supported southern emancipation, in war or otherwise. Lincoln’s law was a form of creative destruction: the idea that moving forward required obliterating previous acts and beliefs. Prior to 1863, Lincoln favored gradual and compensated emancipation plans, including those linked to colonization. Faced with a devastating war, he blew past these gradualist limits. As one black correspondent put it, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation proved that the world had changed.

Lincoln’s edict would not have happened without abolitionist prodding and support. Throughout the war, local antislavery societies petitioned Congress to proclaim emancipation while the abolitionist press continually hammered Lincoln. A striking example comes from George Stephens, a free black correspondent for the Weekly Anglo-African newspaper who served as an aid to a Union officer. Stationed on the Virginia-Maryland border, Stephens watched runaway slaves stream into Union lines. Challenging Lincoln, he wrote that southern blacks were “a power that cannot be ignored.”

On the international scene, abolitionists made the Confederacy a pariah. In Great Britain, a cadre of expatriate African Americans, including William Wells Brown, Sarah Parker Remond, and Ellen and William Craft, helped to convince Britons to stay out of the war. Working with British abolitionists, they focused on manufacturers and workers who grew worried that the lack of southern cotton would shutter English factories (the United States supplied more than 75 percent of England’s raw cotton). Remond, a longtime member of the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society and a traveling lecturer for the American Anti-Slavery Society, resettled in London and gave more than fifty speeches on the duty of the English people to oppose the Confederacy. As she put it in an 1862 speech, “[l]et no diplomacy of statesmen, no intimidation of slaveholders, no scarcity of cotton, no fear of slave insurrections, prevent the people of Great Britain from maintaining their position as the friend of the oppressed negro.”

Black troops and abolitionism

With the Emancipation Proclamation in full force, many abolitionists supported the use of black troops. In late 1862, Massachusetts abolitionist Thomas Wentworth Higginson led one of the inaugural regiments of former slaves: the First South Carolina Volunteers. Organized under the Militia Act of 1862, which allowed the use of black troops in special circumstances, the “First South” was comprised mostly of fugitive slaves. Under Higginson, who spent the previous decade helping the Boston Vigilance Committee protect fugitive slaves, the First South engaged in spying, raiding, and recruitment operations in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. In its first campaign, the regiment struck at rice plantations along the Georgia-Florida border, freeing more than 150 enslaved people, many of whom became Union soldiers.

The success of the First South, the First Kansas Colored Infantry, and other test regiments helped convince the Republican-dominated Congress to authorize black troops. In February 1863, Massachusetts organized the most famous black regiment: the 54th Massachusetts. With Frederick Douglass serving as a recruiter, it soon attracted more than one thousand enlistees, including many fugitive slaves. “Men of Color, To Arms!” Douglass urged in recruiting swings through New York, New England, and Pennsylvania. He was proud when two of his sons, Lewis and Charles, answered the call. In North Carolina, William Henry Singleton, an escaped slave who rushed to Union lines at New Bern, mobilized the First North Carolina Volunteers. It was commanded by a familiar name: James C. Beecher, the half-brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Most black regiments were organized under the banner of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). Authorized in May 1863, the USCT comprised 175 regiments during the war. Nearly one hundred and eighty thousand African Americans fought in the Union army and twenty thousand in the Union navy. Perhaps three-quarters of these soldiers were former slaves. Black regiments fought in roughly four hundred battles; approximately forty thousand died, and a dozen black soldiers earned Purple Hearts for bravery. None of this would impress Confederate leaders, who passed a law treating captured black soldiers as slave rebels to be executed (similarly, white Union officers commanding black troops would be tried and executed). On the battlefield, Confederate soldiers often refused to treat blacks according to prevailing wartime conventions. At the Fort Pillow Massacre in Tennessee in April 1864, more than three hundred black troops were killed when Confederates—led by Nathan Bedford Forrest—refused to take African Americans as prisoners of war (surrendering whites were not attacked). Even in a brutal sectional war, such acts of ritual violence stood out.

Not all the action took place in the South. The largest training ground for black troops was Camp William Penn, located just outside Philadelphia. Set on land owned by longtime abolitionist Lucretia Mott, Camp William Penn opened in the summer of 1863. Roughly eleven thousand African American troops would pass through its gates. Black and white abolitionists were frequent visitors to Camp William Penn. On one occasion, Frederick Douglass told troops assembled there that they symbolized the highest aspirations of the new American Union.

Behind regimental lines, African American women played increasingly important roles in the war effort. At many U.S. forts and Union camps, self-emancipated women and children often outnumbered men. African American women worked as nurses, teachers, laundresses, cooks, and aides. Others taught in schools opening up in former slave country. Susie King Taylor, a young enslaved woman from Georgia who fled to Union lines in 1862, taught in a freedmen’s school on St. Simons Island before serving as a nurse with the “First South.” Taylor’s indefatigable efforts won praise from Union officials.

Some black women became valued scouts and spies. Harriet Tubman, dubbed “General Tubman” by John Brown for her militant resolve, served with the Second South Carolina Volunteers, helping strategize an important attack on a Confederate installation along the Combahee River in June 1863 that liberated hundreds of enslaved people. General David Hunter, who commanded the Southeast theatre for the Union Army, saluted Tubman’s work.

Black troops created new optics for abolition. In the 1850s, African Americans were ridiculed in minstrel shows and unflattering songs. During the Civil War, they were increasingly celebrated as brave soldiers and patriotic Unionists. Thomas Nast’s famous sketch, “A Negro Regiment in Action,” symbolized the heroic character of black military service. Showing a charge by black troops that devolved into fierce hand-to-hand combat, the image was featured in Harper’s Weekly, the most important magazine in the United States, in March 1863.

Harper’s consistently covered the exploits of black troops, including the moving story of an enslaved man named Gordon who joined the Union army after running away. In the middle of 1863, the paper showed an image of Gordon’s terribly scarred back to demonstrate “the degree of brutality which slavery has developed among the [southern] whites.” Yet an accompanying image showed Gordon transformed by his military uniform. Gordon’s tale offered a new storyline for the Union: just as he was liberated from bondage, so too would he help the Union liberate itself from the slave power. Even the headline was designed to transform white expectations about African Americans. Entitled “A Typical Negro,” Gordon’s story was that of a fighting black man who put his life on the line for the Union.

The iconography of black soldiers pressed up against the ongoing problem of racial inequality. In 1863, the 54th Massachusetts protested unequal wages in the Union army—a protest that lasted more than a year. Refusing lesser pay than whites ($10 per month versus $13), they argued that the federal government was duty bound to pay black soldiers equally. Not until June 1864 would the matter be rectified.

The pay dispute was just one area of concern for wartime abolitionists. On the northern home front, civic inequality remained the order of the day in many cities and towns. In Philadelphia, William Still protested rigid streetcar segregation that compelled even black soldiers to ride in separate areas. Despite organizing a petition campaign with more than 350 signatures (including white business, political, and cultural leaders), Still could not get private streetcar companies to change their policy. As Douglass put it, the seemingly “Christian city” of Philadelphia was anything but a model of brotherly love.

The worst example of northern prejudice came in the New York City draft riots of July 1863. As Union draft plans were put into place, working-class New Yorkers lashed out at African Americans and abolitionists. Over the course of several days, a largely Irish mob rampaged through the city, killing more than one hundred African Americans, including women and children. Only whenthe Army of the Potomac arrived from Gettysburg was the riot suppressed. This was no momentary issue. Bowing to white fears, New York did not raise its first black regiments until well after other states had, which black and white abolitionists attributed to powerful anti-abolitionist Democrats in state government. To deal with such wrongs, Peter Cooper—builder of Cooper Union, where Lincoln’s presidential bid had taken shape—compelled members of New York City’s elite to publicly support both emancipation and black troops. Cooper’s activism notwithstanding, black and white abolitionists realized that they had to keeping fighting for freedom above the Mason-Dixon line.

Final abolition: The Thirteenth Amendment

The last major drive by abolitionists during the Civil War focused on securing a constitutional amendment to end slavery. By 1864, abolitionists, Radical Republicans, and Lincoln agreed that such an amendment was critical. Not only did the Emancipation Proclamation apply only to Confederate states, leaving roughlyone million enslaved people and fugitive slaves in border states and Union camps, but the prospect of an alliance between conservative Unionists and repatriated masters might mean slavery’s revival at some future date. Slavery needed to be eradicated constitutionally, not just militarily. With abolitionist support, Radical Republicans ensured that no emancipation backsliding would occur.

Ohio abolitionist James Ashley was the first politician to propose an antislavery amendment. The Republican congressman recalled debates over runaway slaves in the Ohio Valley of his youth. A friend and ally of Samuel Chase, he disliked compromise with slaveholders. In December 1863, he argued that an abolitionist amendment to the Constitution would seal slavery’s fate.

Old debates about the ultimate ends of abolition complicated matters. While Ashley favored an amendment that banned bondage, Charles Sumner proposed one that linked black equality to constitutional abolition. A clever politician, Ashley knew that eradicating bondage would be tough enough, and he convinced others to support a stand-alone amendment on slavery. Lyman Trumbull refined the proposed amendment’s language: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” Like the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, upon which the amendment was based, Ashley and Trumbull made the amendment simple and direct.

Abolitionists backed the newly crafted Thirteenth Amendment with vigor. Using the publicity machine that they had perfected through decades of activism, they published editorials, held petition drives, and lectured far and wide on the amendment’s vital nature. Anna Dickinson, a young Quaker abolitionist whose speaking career took off during the war, lectured Congress that slavery must be destroyed along with the Confederacy. The Women’s Loyal National League, launched by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1863, gathered four hundred thousand signatures to pro-amendment congressional memorials. In churches and benevolent societies, African Americans supported the amendment too.

Abolitionist backing was critical, for the election of 1864 proved that emancipation remained embattled in national politics. Former Union general George B. McClellan ran against Lincoln as a peace Democrat who vowed to return the nation to its pre-1860 social and political order. No fan of emancipation, McClellan had a special animus against Lincoln, who had removed him from high command. Though McClellan appeared to have a real shot at winning, Sherman’s conquest of Atlanta settled matters and secured the election for Lincoln.

The election showed that abolitionism, military success, and Republican politicking were tightly linked. Discussion of the proposed Thirteenth Amendment stopped at key moments in 1864. While Ashley and his Republican colleagues pushed the amendment through the Senate in April, the House refused to follow suit in June. Clearly Union Democrats (and even some conservative Republicans) were waiting to see what happened on the battlefield before moving forward.

After Lincoln’s victory in November, Ashley and his allies resumed the amendment push. With some ingenious parliamentary maneuvering, Ashley and his Republican colleagues targeted January 31, 1865, as the day to finalize support for the amendment in the House of Representatives (it had previously passed in the Senate). Getting just enough Democrats on their side for a super majority, which passage of amendments required, Republicans prevailed: 119 in favor, 59 opposed. As a poem in Harper’s soon put it, America was now “free.”

Abolitionists rejoiced. For the first time in their lives, slavery would be illegal. Countless abolitionists and freedom fighters never lived to see national emancipation: Denmark Vesey, Richard Allen, David Walker, Henry David Thoreau, Theodore Parker, Anthony Burns, and thousands upon thousands of enslaved people. Even Lincoln, who never joined an abolition society but became perhaps the greatest abolitionist statesman of the age, died before the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified by the states in December (when Georgia approved it). His assassin, John Wilkes Booth, fired one last shot at Lincoln’s emancipation war. Booth recoiled at the prospect not only of Confederate defeat but also of an abolitionist victory.

By the time Booth struck down Lincoln, black troops had helped end the Civil War in Virginia. In April 1865, roughly two thousand African Americans fought at Appomattox, ensuring that Robert E. Lee would not slip away. The irony was powerful: only a few years before, John Brown and his interracial band sought to foment a slave uprising in western Virginia. They were captured by Lee and the U.S. Army. Now that same army included tens of thousands of runaway slaves, some of whom forced Lee’s rebels to surrender in western Virginia.

In Charleston, black and white abolitionists took particular delight in slavery’s demise. Black troops marched into secession’s longtime capital singing “John Brown’s Body”—a Union anthem based on an old slave spiritual. Greeted by a throng of enslaved people in February 1865, they took the city in the name of the new Union. “Marching On!” Harper’s Weekly declared. In March, Charleston’s black community buried a coffin marked “slavery.” South Carolina had landed more slave-trading vessels than any other American colony or state; now the state witnessed slavery’s last rites.

In April, longtime abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison and Henry Ward Beecher raised the U.S. flag at Fort Sumter. When the Civil War started four years earlier, that flag represented a republic still very much dedicated to slavery. Now it symbolized the new birth of freedom that promised equality and justice for all Americans. For the first time in his life, Garrison recalled, he felt proud to be an American.

In Texas, news of slavery’s demise would not reach enslaved people for two more months. On June 19, 1865, Union general Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston with General Orders Number 3, which declared that, in accord with Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, “all slaves are free.” While black people celebrated, the first “Juneteenth” Proclamation was also accompanied by fear. Until ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment by the states was complete, African Americans worried that slaveholders would retaliate against liberated slaves. If it had taken years to hear about the Emancipation Proclamation in Texas, where Deep South masters had gathered as a last redoubt of bondage, perhaps black freedom would always be a precarious proposition. Even today, Juneteenth celebrations serve as a potent reminder that we can never take freedom for granted.