I am a human, and nothing human is alien to me.

—Terence

Within the Four Seas, all are brothers.

—Zigong

In the previous chapter I called for greater inclusivity and openness to philosophy outside the mainstream Anglo-European canon. I dropped the names of a few texts, thinkers, and issues that could contribute substantially to a broader dialogue. However, it is fair to ask for more detailed examples. Consequently, in this chapter I provide a few specific illustrations of how different intellectual traditions can be brought into dialogue. Some readers will be disappointed to discover that my comparisons are only between a handful of Asian and European philosophers. However, I can only responsibly discuss the areas in which I claim competence. To advocate that we teach the less commonly taught philosophies (LCTP) is not to suggest the unrealistic goal that we should all be equally adept at lecturing on all of them. Moreover, I do not go into nearly as much depth in this chapter as would be appropriate in a purely academic work. Nonetheless, even the selective, cursory discussions in this chapter demonstrate conclusively just how much room there is for productive dialogue between traditions.

Philosophers—who, as a group, are known for not agreeing about anything—agree that modern Western philosophy begins with René Descartes (1596–1650). There is almost as much of a consensus that modern Western political philosophy begins with Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679).1 The two disagreed about a great deal.2 Hobbes asserted that “the universe, that is, the whole mass of all things that are is corporeal—that is to say, body.”3 Descartes, in contrast, believed that, in addition to physical objects, the universe includes souls that are incorporeal and immortal. However, Descartes and Hobbes agreed on a fundamental claim: the universe is composed of distinct individual entities. Although there have been occasional philosophers who have dissented from this view (most notably Parmenides, Spinoza, and Hegel), individualistic metaphysics is something like the orthodoxy in Western philosophy.4 This belief has been developed in various ways, but it is so fundamental to Anglo-European philosophy that it generally has not been seen as requiring demonstration. The issue has not been whether we are distinct individuals, but how we are fundamentally distinct and what the implications of this are. However, if we assume that individuals are distinct, it creates a number of problems in metaphysics (our account of the most fundamental kinds of things that exist and how they are related), political philosophy (our conception of how and why human communities should be organized), and ethics (our view of the best way for a person to live). We shall see that Buddhist, Confucian, and Neo-Confucian philosophies offer alternatives on these topics that are undeniably worth taking seriously.

In his major philosophical works, Discourse on Method and Meditations on First Philosophy, Descartes argues that there are two distinct kinds of substances in the universe: things that think (souls) and things that occupy space (material objects).5 His use of the word “substance” is potentially misleading for us. When we talk about a “substance,” we are typically talking about something that lacks individual identity (especially if it is disgusting): “Ew, what is this substance stuck to the bottom of my shoe?” For Descartes, “substance” is a technical philosophical term, which he inherited from Aristotle (384–22 BCE). Aristotle defined a substance as a thing that has qualities but is not itself a quality of anything else.6 For example, the color red is not a substance, because it is a quality of something else, like a fire hydrant. But a fire hydrant is not a quality of anything else, so it is a substance. The thesis that the universe is divided into qualities of various kinds and the things that they are qualities of sounds simple and accurate. However, as Aristotle himself came to recognize, this seemingly straightforward account generates problems as soon as we think more carefully about what it means.7 Let’s return to Descartes to see how.

In trying to explain what a material object (a substance that occupies space) is, Descartes invites us to consider a piece of wax, fresh from the beehive, and its sensory qualities. It has the taste of honey, a floral scent, is hard and cold to the touch. However, if you melt the same piece of wax, it loses its taste and odor, changes its shape, and feels hot and soft. Descartes then asks his readers, “does the same wax remain? One must confess that it does: no one denies it; no one thinks otherwise. What was there then in the wax that was so distinctly comprehended? Certainly none of the things that I reached by means of the senses. For whatever came under taste or smell or sight or touch or hearing by now has changed, yet the wax remains.”8

The material thing that remains the same through the various changes is the substance. But what is this substance? You cannot identify the substance with any properties, like being hot or cold, hard or malleable. The substance is the thing that has these qualities, and remains the same as the properties change. This led Aristotle to suggest at one point that there must be what he called “prime matter,” a quality-less substratum that is the bearer of properties.9 Something seems incoherent, though, about the notion of a thing that has an identity but no properties.

Descartes compares our knowledge of substances to seeing people out his window, crossing the street in the dead of winter, completely bundled up in clothes: “But what do I see over and above the hats and clothing? Could not robots be concealed under these things? But I judge them to be men.”10 Similarly, “when I distinguish the wax from its external forms, as if having taken off its clothes, as it were, I look at the naked wax.”11 (How quaint Western philosophy is, with all its little similes and metaphors!) The problem, of course, is that we have seen people without their coats and hats on, and we know what they look like. In contrast, we have not seen wax without its “external forms.” As Descartes admits, we know the wax in itself “neither by sight, nor touch, nor imagination.”12

Descartes discusses space-occupying substances as a step toward understanding what a thinking substance is. However, his account of souls inherits all the problems that afflicted his account of material objects. Souls engage in mental acts like thinking, perceiving, and willing. But none of these acts are what the soul is. The soul is the underlying thing that does the thinking, perceiving, and willing. And your soul is supposed to be different from mine, even if you and I are thinking the very same thing. What makes one soul different from another if the acts of the soul are not what make it what it is?

The puzzles of personal identity are illustrated by the film Regarding Henry (1991), in which Harrison Ford plays an attorney who is shot in the head during a convenience store robbery. After brain surgery, Henry’s memories are gone. He does not recognize his wife, his children, or his colleagues from work. Prior to his brain injury, Henry was a brilliant but also heartless lawyer. Afterward, he seems to have only average intelligence, but is kind and loving. Is he the same person before and after brain surgery or not? According to Descartes, there is a definitive answer: the same soul is attached to his body, so he is the same person. But this answer seems unsatisfying because all the qualities of the soul that seemed to make Henry who he was have changed. Perhaps it is the same Henry because he has the same body? However, Henry’s body is actually not the same. His brain, the physical organ we probably associate the most with our identity, has suffered significant trauma. So perhaps we should say that Henry1 (before brain trauma) and Henry2 (after brain trauma) are different people? But our bodies (and our mental states) are changing all the time. My brain and my mind at birth are immensely different from my brain and mind today. Am I not the same person? Or do only sudden and significant changes in the brain or mind make us a new person? How significant must a change be in order to count as making someone a new person? If these questions seem vexing, perhaps it is because we started with the wrong assumption: that there is an unchanging self that persists through qualitative change.13

Descartes’s only real argument that there must be individual substances distinct from all of their qualities is that “no one denies it; no one thinks otherwise.”14 Well, actually, some people have denied this. The Buddhist tradition argues that there are five kinds of states that exist: physical states (being hard or malleable, hot or cold, etc.), sensations (experiences of physical or mental states, which may be pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral), perceptions (conceptual identification of that which one senses), volitions (such as desiring, willing, and choosing), and consciousness. Buddhists call these the “Five Aggregates.” A concrete example will clarify what sorts of things they are: Suppose I am in the presence of a plate of freshly baked chocolate chip cookies. The visual receptors in my eyes are stimulated by the light reflected off the cookies, while molecules liberated by the heat of the cookies stimulate the olfactory receptors in my nose. As a result of these physical states, I have a visual sensation of golden brown circles with dark brown spots against a white background, and the pleasant olfactory sensation of baked dough, brown sugar, and just a hint of vanilla. These sensations are followed by a perception: the identification of what I am sensing as chocolate chip cookies. At this point, I develop a volition, a desire to eat the cookies—all of them, right now, in one sitting. However, I also have consciousness, which allows me to be aware of and think critically about my mental states. I may remind myself that eating a couple of cookies is pleasant, but I will feel an unpleasant sugar rush if I eat all of them at once, thereby reconceptualizing my choice in a way that leads to moderate consumption. (In the case of cookies, this last step never happens for me, but you get the idea.)

Of course, this simple example does not do justice to the complexity of the concept of the Five Aggregates. As Jay Garfield points out, Buddhist accounts of “consciousness” do not map neatly onto those in Western philosophy of mind (even though they are debated with the same level of subtlety).15 What is important to grasp is that Buddhist metaphysics regards the world as composed of transient states and properties that are causally dependent on other states and properties. It does away with the notion of metaphysical substances or prime matter as explanatorily useless. This ontology of states rather than things has substantial (pardon the expression) implications for how we think about ourselves.

In the second century BCE, in what is now Pakistan, the Buddhist monk Nāgasena arrived for a royal audience with King Milinda. When Milinda asked him his name, the monk replied that he is called “Nāgasena,” but “this ‘Nāgasena’ is only a designation, a label, a concept, an expression, a mere name because there is no person as such that is found.”16 Milinda and Nāgasena proceed to have a subtle philosophical debate over what it means to say that there is “no person.” (At this same period in history, Descartes’s and my ancestors in Europe were illiterate barbarians bashing one another with clubs.) They consider three suggestions about what a self would be: Is the self identical with one of the Five Aggregates? Is the self identical with all of the Aggregates? Is the self something distinct from all of the Aggregates? Nāgasena and Milinda are obviously both familiar with previous Buddhist arguments against the reality of the self, so they quickly agree on negative answers to all three questions. (1) The self cannot be identified with a person’s nails, “teeth, skin, flesh, sinews, bones, bone marrow, kidneys, heart, liver … brain, bile, phlegm, pus, blood, sweat,” or any physical thing.17 As the Buddha himself had explained, nothing physical could plausibly be identified as the self because, qua physical thing, it has no experiences: “If, friend, no feeling existed, could there be the thought, ‘I am’?”18 In other words, identifying the self with any physical thing violates our intuition that the self is conscious. One of the other Aggregates might seem a better candidate for the self, since they each involve consciousness in some way. However, suppose we identified the self with a pleasant sensation. The Buddha explains why this is also unsatisfactory: “So anyone who, on feeling a pleasant feeling, thinks ‘This is my Self,’ must, at the cessation of that pleasant feeling, think, ‘My self has departed!’ ” This violates our intuition that the self is something that persists over time. The same applies to any other kind of sensation, as well as to any instance of the other mental Aggregates. (2) What about the possibility that the self is identical with all of the Aggregates taken together? Upon reflection, we see that this will not work either. Since each of the Aggregates is changing individually, the combination of them taken together is also changing, and so cannot be a permanent self: “It is just like a mountain river, flowing far and swift, taking everything along with it; there is no moment, no instant, no second when it stops flowing, but it goes on flowing and continuing. So … is human life, like a mountain river. The world is in continuous flux and is impermanent.”19 This is very similar to the famous claim of the Greek philosopher Heraclitus, who “says that all things pass and nothing stays, and comparing existing things to the flow of a river, he says you could not step twice in the same river.”20 (Of course, some people seem to think that, when Heraclitus says this, it is philosophy, but when a Buddhist says the same thing, it is not philosophy.)

(3) Is the self then something different from the Aggregates? This would be something like Descartes’s view. The king asks Nāgasena about a very similar position in another part of their extensive dialogue:

“Revered Nāgasena, is there such a thing as an experiencer?”

“What does this ‘experiencer’ mean, sire?”

“A soul within that sees a visible form with the eyes, hears a sound with the ear, smells a smell with the nose, tastes a taste with the tongue, feels a touch with the body and discriminates mental states with the mind. Just as we who are sitting here in the palace can look out of any window we want to look out of, even so, revered sir, this soul can look out of any door it wants to look out of.”21

Nāgasena argues that it is unclear how to understand the relationship between such a soul and the body that it is supposed to “look out of.” If the soul sees, why does it need the eye at all, for example? Why can’t the soul see as well, or even better, without the organ of the eye? Of course, the soul does use the eye to see, and does not see better when the eye is removed. But then, Nāgasena suggests, why not adopt a simpler alternative: “Because, sire, of the eye and visible form eye-consciousness arises.… The same applies to the ear and sound, nose and smell, tongue and taste, body and touch, and mind and mental states. These are things produced from a condition and there is no experiencer found here.”22 In other words, the Aggregate of consciousness is different for each kind of consciousness, and arises simply as a result of the interaction between the intentional object of consciousness (for example, a color) and the sense organ (for example, an eye). Reference to some mysterious “experiencer” beyond the interaction between the color and the eye adds nothing to the explanation.

The metaphysical arguments against a self seem unanswerable, but what concerns King Milinda is the problematic ethical implications that they appear to have. If there is no self, who is it who engages in virtuous or vicious conduct? Who is it who is ignorant or enlightened? As King Milinda notes, the doctrine of no-self seems to lead to ethical nihilism: “revered Nāgasena, if someone were to kill you there would be no murder.”23 It appears that there would be no self who murders and no self who is murdered, and hence no wrongdoing.

Nāgasena replies with the simile of the chariot. He asks the king, “did you come on foot or in a vehicle?”24 The king replies that he came in a chariot. Nāgasena then applies the same antisubstantialist argument to the chariot that they had applied to Nāgasena himself. Is a chariot the same as its wheels? Clearly not, because you can repair the wheels and it will be exactly the same chariot. Is the chariot the axle? No, we would refer to it as the same chariot even if the axle were completely replaced. Is the chariot the yoke, reins, goad, or flagstaff? No, no, no, and no, for the same reasons. Nāgasena teasingly tells the king that he was obviously not telling the truth when he said he rode here in a chariot, since he can identify no thing that is the chariot: “You are king over all India, a mighty monarch. Of whom are you afraid that you speak a lie?”25 Milinda protests that he is not lying, and that “ ‘chariot’ exists as a mere designation” based upon the various parts.26

“Even so it is for me, sire,” Nāgasena explains. “ ‘Nāgasena’ exists as a mere designation,” used in the presence of his physical form, consciousness, etc. “However, in the ultimate sense there is no person as such that is found.” He then quotes some verses attributed to a Buddhist nun and praised by the Buddha himself:

Just as when the parts are rightly set

The word “chariot” is spoken,

So when the there are the aggregates

It is the convention to say “a being.”27

It is easy to misunderstand Nāgasena’s position here. He is not claiming that there is a thing that is the chariot (or a person) and that it is identical with the combination of the relevant Aggregates. (We saw earlier why this won’t work.) Instead, he is suggesting that, in the presence of certain combinations of Aggregates, we follow social convention in using the word “chariot” (or “Nāgasena”). In other words, there is no thing that is oneself; the Cartesian thinking substance is an illusion. However, this does not mean that we can or should stop calling one another “Nāgasena,” or “Milinda,” or “Bryan,” or “Barack.” To do so is useful for practical purposes, and what guide us are social conventions about linguistic usage. Similarly, we can continue to say things like “Charles Manson is a bad person” or “Mother Teresa was very enlightened.” But these claims do not require that there is some unique metaphysical entity that a proper name refers to that remains the same over time.

Returning to our earlier example from the film Regarding Henry, Nāgasena would say that there is no fact about whether Henry is the same person. It is a matter of social convention whether we regard him as such. There is a collection of changing physical and mental states prior to the shooting and there is a collection of transient psychophysical states after the shooting, and our social convention is to call them both “Henry.” This is reflected in the fact that the family and colleagues of “Henry” prior to the shooting welcome “him” back after the shooting (and prefer the way “he” is now). Notice that similar considerations could apply to abortion. For a Cartesian, there is a fact about when the fetus is “ensouled,” and from that moment on it is the same person. To end the life of an ensouled body is the moral equivalent of murder. However, the problems with defining when human life begins suggest that an application of Nāgasena’s view is more appropriate. We do not discover when human life begins; we decide when life begins, trying to do so in a way that is as humane as possible.28

The preceding view is characteristic of Theravāda, which nonsectarian historians regard as the earlier form of Buddhism. Mahāyāna Buddhism, the dominant form in East Asia, would not deny anything Nāgasena said, but extends it in a new direction. We might say that Theravāda argues that there is no self, while Mahāyāna claims that there is no individual self. The Tang-dynasty Chinese Buddhist philosopher Fazang (643–712) wrote a philosophical dialogue that is representative of one strand of the Mahāyāna position.29 Fazang asks us to consider a building.30 What makes a building a building? Surely it is nothing other than the parts that make it up. There is no thing in addition to its parts that constitutes the building. So what are the parts of the building? Consider an individual rafter: What makes it a rafter? Fazang argues that it is a rafter because of the role that it plays in constituting the building. One might object that the rafter would still exist even if the rest of the building did not. Fazang replies that then it would no longer be a rafter. (For example, a plank that had been a rafter might be repurposed as a bench. We might want to say, “This bench used to be a rafter,” but it would not be plausible to say, “This bench really is a rafter, despite the appearance that it is a bench.”) What makes a rafter a rafter (as opposed to a bench or a teeter-totter) is the role it plays in the building. So the rafter is dependent on the building for its identity, but we already saw that the building is identical with all its parts. Consequently, the rafter is dependent on all the other parts of the building for its identity: the rafter depends on each of the other rafters, each of the shingles, each of the nails, and so on. But what is true of the rafter in relation to the building is true of anything in relation to the entire universe.

Fazang summarizes his point with a slogan: “All is one, because all are the same in lacking an individual nature; one is all, because cause and effect follow one another endlessly.”31 “All is one,” because the entire universe is nothing else beyond the particular configuration of transient physical and mental states in causal relationships that make it up. “One is all,” because any one thing is what it is because of its relationships with all the other things that define it. The building is the building because of each of the parts that make it up (“all is one”), but the rafter is a rafter because it is a part of the building (“one is all”). As a matter of brute causal fact, the universe we live in would collapse like a house of cards if some malevolent higher power plucked out of the causal web the lowliest member of the army of Alexander the Great, or your third cousin twice removed. It is not poetry but the most relentless logic of cause and effect that demonstrates that the last breath of Julius Caesar is my morning cup of coffee; the entire universe is a speck of dust; and I am you. A universe without you, or even a universe without this particular grain of sand, is as completely fictional as Hogwarts or House Lannister.

Ray Bradbury’s seminal short story “A Sound of Thunder” (1952) gives a colorful example of the way in which events separated by immense gulfs of space and time can be substantially connected. In the story, a time traveler goes back to the Jurassic era and accidentally steps on a butterfly. When he returns to the present, he finds that the course of history has been modified, in some ways that are trivial, but in some ways that are disastrous. Bradbury’s story is more than speculation, because scientists have known since the nineteenth century that minute changes in the initial conditions of deterministic systems can lead to immense changes in the later states of that system: Henri Poincaré noted this in regard to “the three-body problem” in physics.32 Then, in the twentieth century, Edward Lorenz helped bring about a minor revolution in science by showing a similar phenomenon in meteorology: extremely small atmospheric changes (like the beating of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil) can have massive consequences (like a hurricane in Florida).33 In honor of Bradbury, this scientific truth is now called “the butterfly effect.” While the significance of causal connections may not always be as dramatic as in Bradbury’s story, it seems undeniable that it is possible to trace relations between any two things in the universe. If it seems difficult to imagine what relation exists between Diego, my French bulldog, and Charon, the largest of the moons of Pluto, keep in mind that the two exert a gravitational pull on each other (gravity decreases as the inverse square of distance but never disappears) and both were created in the same Big Bang.

Consider how this understanding transforms our conceptions of ourselves. Who am I? I am a husband, a father, a teacher, an author, and a US citizen, among other things. But each of these properties is relational: I am a husband because I have a spouse, a father because I have children, a teacher because I have students, an author because I have a readership, a US citizen because of historical facts and institutional structures I participate in. But the things I am related to are also defined by me.34

Thomas Hobbes shared Descartes’s radical metaphysical individualism, arguing that there is “nothing in the world universal but names, for the things named are every one of them individual and singular.”35 For this reason, Hobbes’s political philosophy is in many ways the natural counterpart of Descartes’s metaphysics. Just as Buddhism helped us see alternatives to individualistic metaphysics like that of Descartes, Confucianism will help us to see the limitations of individualistic political philosophies like that of Hobbes.

Hobbes’s political project is to explain how government authority can be justified, on the assumption that each human is originally completely independent, metaphysically and ethically, from every other human. Hobbes also appears to assume that each human being is purely self-interested: “of the voluntary acts of every man, the object is some good to himself. ”36 Consequently, “if any two men desire the same thing … they become enemies; and in the way to their end, which is principally their own conservation, and sometimes their delectation only, endeavor to destroy or subdue one another.”37 Given these assumptions, Hobbes concludes that the natural state of human beings is “a condition of war of every one against every one.”38 In this conflict, one individual may have some marginal physical or intellectual advantage over another. However, these do not make a significant difference, since even “the weakest has strength enough to kill the strongest, either by secret machination or by confederacy with others that are in the same danger with himself.”39 Consequently, life in the state of nature is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short,”40 like the worlds portrayed in the film Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) and the television series The Walking Dead (2010–present).41

This situation might seem to make legitimate government authority impossible, but Hobbes argues that, on the contrary, it is precisely what makes government a rational necessity. In humans’ natural state of merciless competition “there can be no security to any man, how strong or wise soever he be, of living out the time which nature ordinarily allows men to live.” Consequently, it is a law of nature “that a man be willing, when others are so too, as far forth as for peace and defense of himself he shall think it necessary, to lay down this right to all things, and be contented with so much liberty against other men as he would allow other men against himself.”42 Humans therefore can and do enter into a “covenant” to renounce violence, dishonesty, and thievery against one another. Now, since “covenants without the sword are but words, and of no strength to secure a man at all,”43 it is necessary that there “be some coercive power to compel men equally to the performance of their covenants by the terror of some punishment greater than the benefit they expect by the breach of there covenant.”44 This coercive power is provided by the government. In summary, humans naturally have a right to do anything, including harming and killing others, in the pursuit of their individual self-interests. However, everyone will suffer horribly in this situation. Consequently, humans agree to renounce most of their rights to the government in exchange for protection from other people. In order for this to succeed, government must have an exclusive and in principle unlimited right to use force to compel adherence to its laws. Although government restricts our natural liberty, we are better off under even the most authoritarian government than we are in the state of nature.

Hobbes’s philosophy is ingenious, but it faces several insurmountable problems. In a passage that seems almost tailor-made as a response to Hobbes, Confucius (551–479 BCE) argues that “if you try to guide the common people with coercive regulations and keep them in line with punishments, the common people will become evasive and will have no sense of shame. If, however, you guide them with Virtue, and keep them in line by means of ritual, the people will have a sense of shame and will rectify themselves.”45 The Confucian critique of authoritarian positions like that of Hobbes is that, no matter how severe the punishments and how intrusive the government surveillance, people will endlessly devise ways to evade the laws so long as their only motivations for compliance are self-interested. In contrast, if humans can cultivate compassion and integrity (“Virtue”) and respect for social conventions that they regard as sacred (“ritual”), the laws and punishments will be almost unnecessary.46

Mengzi, a philosopher of the fourth century BCE, defends Confucius’s political thesis, arguing that a state can be prosperous in the long run only insofar as its citizens are motivated by benevolence (compassion for the suffering of others) and righteousness (disdain to do what is shameful, like lying and cheating). In contrast, being motivated by profit—even if it is the profit of a group to which one belongs—is self-undermining. Mengzi warns a ruler:

Why must Your Majesty say “profit”? Let there be benevolence and righteousness and that is all. Your Majesty says, “How can my state be profited?” The Counselors say, “How can my family be profited?” The scholars and commoners say, “How can I be profited?” Those above and those below mutually compete for profit and the state is endangered.… There have never been those who were benevolent who abandoned their parents. There have never been those who were righteous who put their ruler last. Let Your Majesty say, “Benevolence and righteousness,” and that is all. Why must you say “profit”?47

Mengzi demonstrates a further problem with Hobbes’s philosophy: its vision of human nature is not just ugly; it is also demonstrably mistaken. Mengzi presents a thought-experiment aimed at an egoist in his own era, Yang Zhu, that is equally effective against Hobbes:

The reason why I say that humans all have hearts that are not unfeeling toward others is this. Suppose someone suddenly saw a child about to fall into a well: everyone in such a situation would have a feeling of alarm and compassion—not because one sought to get in good with the child’s parents, not because one wanted fame among their neighbors and friends, and not because one would dislike the sound of the child’s cries. From this we can see that if one is without the heart of compassion, one is not a human.48

Every aspect of Mengzi’s thought-experiment is carefully chosen. Notice the following points. (1) Mengzi asks us to imagine a case in which a child is in danger. Children, since they are innocent and nonthreatening, trigger our compassion more easily than adults. (2) We are supposed to imagine that a person suddenly sees the child. The suddenness is important, because it suggests that the reaction will be unreflective. There is no time to think about who the child’s parents are, or what rewards might come from saving the child, or even whether it would be annoying to listen to the child cry all night as it struggled to stay afloat in the well. All that the instantaneous reaction can represent is one’s feelings for the child in danger. (3) This passage is often misquoted as stating that any human would save the child at the well; however, Mengzi does not commit himself to anything as strong as that. He merely states that any human in such a situation would have a “a feeling of alarm and compassion.” The feeling could be fleeting. Perhaps one’s second thought would be about how one hates the child’s parents and would love to see them suffer, or self-interested fear that one might fall into the crumbling well oneself if one attempted to save the child. All Mengzi is arguing for is the universal human capacity to feel genuine compassion in at least some circumstances. (4) Mengzi invites us to consider what we would say of someone who did not have at least a fleeting feeling of compassion when suddenly confronted with a child about to fall into a well. He suggests—plausibly, I think—that we would describe such a person as “inhuman.” “Psychopath” is the technical term for beings who lack even this minimal compassion for others. We can quibble over whether they are technically not human, but we certainly agree that they lack something crucial to normal humanity.

In summary, Mengzi’s child-at-the-well thought-experiment describes a reaction to a child (a paradigmatic object of compassion) that is sudden (so there is no time to formulate ulterior motives). Mengzi only claims that any human in this situation would at least have a momentary reaction of alarm and compassion (he does not claim that everyone would act to save the child), and he suggests that we would regard someone who lacked such a reaction as an inhuman beast (rather than a human being). Elsewhere, Mengzi expresses his view of human nature concisely as “Benevolence is what it is to be human.”49

Contemporary developmental psychology supports Mengzi’s view that normal humans have an innate but incipient disposition toward compassion.50 Intuitively, we should not be surprised in the least that humans have evolved a disposition to care for the well-being of others. Like other primates (and like canids, cetaceans, and elephants), we humans are pack animals whose survival depends upon a mutual willingness to make sacrifices for others, typically without any certainty of payback. Darwin himself offered an account of the evolution of moral motivations,51 and more formal demonstrations of how evolution selects for altruism have been provided by recent biologists.52

Mengzi’s alternative conception of human nature leads to a very different view of humans in the state of nature. Humans naturally live in groups, and naturally work together to solve common problems. Government is important because it can harness the human tendency toward group loyalty for the benefit of all. Mengzi claims that, in ancient times, “the waters overflowed their courses, inundating the central states. Serpents occupied the land, and the people were unsettled. In low-lying regions, [people] made nests in trees. On the high ground, they lived in caves.” In response to these problems, a sage arose who organized people who “dredged out the earth and guided the water into the sea, chasing the reptiles into the marshes.”53

Mengzi does not hold some Pollyannaish vision of humans as never engaging in conflict. He recognizes that military and police force will sometimes need to be used. However, he thinks that crime is generally a product of poverty: if the people “lack a constant livelihood … [w]hen they thereupon sink into crime, to go and punish them is to trap the people.”54 Confucius was making the same point when he advised a ruler who was concerned about the prevalence of robbers in his state: “If you could just get rid of your own excessive desires, the people would not steal even if you rewarded them for it.”55

In addition to the fact that controlling the people solely through appeals to narrow self-interest and the threat of violence is impractical, and the fact that Hobbes’s psychology is unrealistic, there is a third major problem with Hobbes’s political philosophy. As we saw in considering Buddhist critiques of Descartes’s view, it is implausible that humans are ultimately metaphysically distinct from one another. But what are the political implications of the Buddhist view? The movement known as “Neo-Confucianism” appropriated the insights of Buddhism in order to provide a metaphysical basis for its own distinctive political philosophy and ethics. Cheng Hao (1032–85) expressed the Neo-Confucian view clearly with a metaphor: “A medical text describes numbness of the hands and feet as being ‘unfeeling.’ This expression describes it perfectly. Benevolent people regard Heaven, Earth, and the myriad things as one Substance. Nothing is not oneself.”56 Cheng is comparing being numb or “unfeeling” toward one’s own limb with being “unfeeling” toward another person. Something is wrong if we are numb in one of our feet because we might allow it to become damaged and not be motivated to do anything about it. Our numbness makes us fail to act appropriately toward what is a part of us. Similarly, being unfeeling toward the suffering of another is a failure to respond with appropriate motivation and action toward what is, ultimately, a part of ourselves.

But can we really accept the ethical and political implications of the view that there are no individual selves? This is the issue that divided the Buddhists and the Neo-Confucians. Their disagreement had a metaphysical aspect and an ethical aspect. Metaphysically, Buddhists like Fazang claim that we are all aspects of a transpersonal self. Because an enlightened being sees all humans as equally parts of one whole, he or she rejects selfishness and loves everyone equally. However, this view also leads the fully enlightened person to reject romantic love and filial piety, because each of these is an attachment of one (illusory) individual to other (illusory) individuals. (This is why Buddhist monks and nuns in most cultures are celibate.) As Fazang puts it: upon achieving enlightenment, “the feelings are extinguished, and the dharmas that are manifestations of Substance become blended into one.”57

Neo-Confucians were drawn to the Buddhist view that benevolence is justified by the metaphysical fact that we form “one body” with others. However, they harshly criticized Buddhists for challenging the value of conventional familial relationships,58 and argued that the Buddhists went too far in undermining the notion of the individual. When one of his disciples announced happily, “I no longer feel that my body is my own,” Cheng Hao smiled and replied, “When others have eaten their fill are you no longer hungry?”59 Consequently, Neo-Confucians tweaked the Buddhist metaphysics: they argued that, in order for things to be defined by their relationships to other things, there must be individual things that stand in those relationships. How can you have a relationship without things that are related by it? (More abstractly, a relationship is of the logical form aRb, where a and b are individuals that stand in the relationship R. Without the distinct individuals a and b to relate, there is no relationship R.) For example, if the rafter is defined by its relationship to other parts of the building, like the nails and shingles, there must be bits of wood, metal, and tile (these specific individual entities) in order for them to stand in the relationship of being-parts-of-the-building. Similarly, the relationship of motherhood does not exist unless there is at least one specific person who is a mother and another specific person who is her child; the property of being a student does not exist unless there is at least one individual who stands in the student-of relationship to one other individual. The great Neo-Confucian philosopher Zhu Xi (1130–1200) explained it like this, using the term “Pattern” to describe the web of relationships among entities: “It’s like a house: it only has one Pattern, but there is a kitchen and a reception hall.… Or it’s like this crowd of people: they only have one Pattern, but there is the third son of the Zhang family and the fourth son of the Li family; the fourth son of the Li family cannot become the third son of the Zhang family, and the third son of the Zhang family cannot become the fourth son of the Li family.”60 Consequently, romantic intimacy, filial piety, and other attachments are justified because there genuinely are individual husbands who love their individual wives, individual children who respect their individual parents, and so on.

I worry that the Neo-Confucians have fallen back into a paradoxical notion similar to a Cartesian substance or Aristotelian prime matter: the quality-less individual that stands in relationships but is not defined by them. However, there is something very appealing about the Confucian effort to do justice both to the fact that we are dependent upon others and to the fact that we are individuals with our own needs, goals, life histories, and attachments.

During his reelection campaign in 2012, President Barack Obama gave a speech in which he (unknowingly) expressed this Confucian perspective:

If you were successful, somebody along the line gave you some help. There was a great teacher somewhere in your life. Somebody helped to create this unbelievable American system that we have that allowed you to thrive. Somebody invested in roads and bridges. If you’ve got a business—you didn’t build that. Somebody else made that happen.… The point is, is that when we succeed, we succeed because of our individual initiative, but also because we do things together.61

This statement was widely criticized by conservatives, who saw it as an attack on the achievements of individual business owners and their right to profit from the fruit of their labor.62 However, for those who have learned the lessons of Neo-Confucianism, Obama’s statement is simple common sense.

I am not a businessman, but I too am proud of my accomplishments. I am proud of having taught generations of students, and of publishing a number of books and articles. I believe that my successes in teaching and publication would not have occurred without my hard work and ability. However, I suffer from no delusions that I am some sort of intellectual Robinson Crusoe.63 I know that I did not single-handedly come up with every idea and methodology I have ever depended upon as a stepping-stone to developing my own original thoughts. I am indebted to my parents for giving me opportunities they did not have. My career is dependent on every teacher I have had from first grade through graduate school. And, of course, my roles as teacher and author are completely dependent upon my students and my readers. So you should look with pride upon your individual accomplishments, but you should also not lose sight of the fact that you did not do that alone.

Confucians are certainly not the only political theorists in China. Mozi argued two millennia before Hobbes that conflict in the state of nature necessitates the establishment of government. Moreover, Mozi’s version of this argument is more plausible than that of Hobbes, because Mozi does not assume that humans are self-interested. He argues that the conflict in the state of nature arises from the fact that humans have different conceptions of right and wrong.64 Legalists like Shen Dao and Hanfeizi argued that humans are largely (although perhaps not exclusively) self-interested, and so governments can only succeed through explicit and clear laws that are enforced with lavish rewards for compliance and severe punishments for transgression.65 This chapter only scratches the surface of Chinese political thought.

Closely related to the issue of how society should be structured is the fundamental question of ethics: How should one live? In his seminal book After Virtue, Alasdair MacIntyre argued that modern Western ethics is fundamentally incoherent because it turned its back on the insights of Aristotelian thought. I am sympathetic to much of MacIntyre’s critique. However, we shall see that Confucian views of ethical cultivation can provide plausible alternatives to the Aristotelian conception.

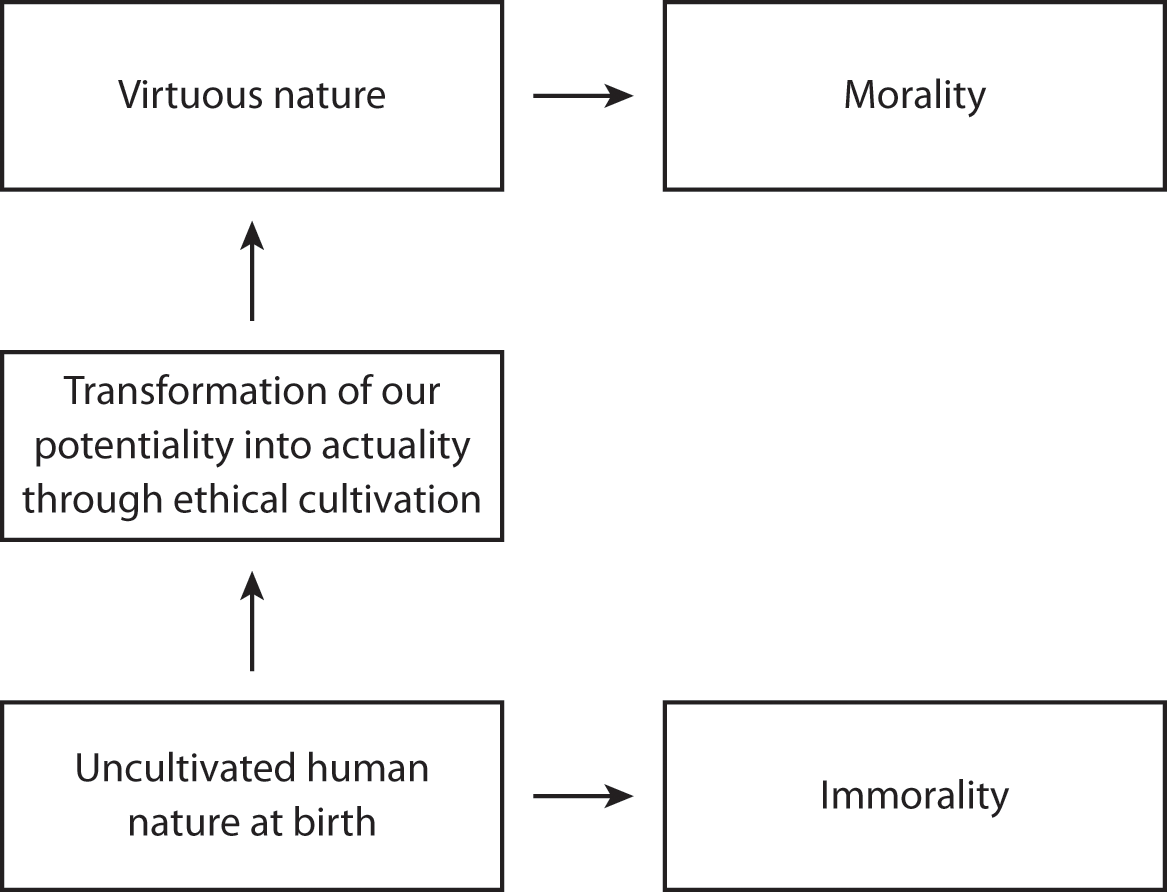

MacIntyre argues that modern ethics inherited an ethical framework from medieval Aristotelianism but dropped one of the parts necessary to make sense out of it.66 According to the classical conception, humans are born with an uncultivated nature characterized by various drives, intellectual faculties, and most importantly ethical potentialities. Without cultivation, these drives lead to immorality (cruelty, dishonesty, etc.) as well as self-destructiveness. Through ethical cultivation, humans shape their drives, hone their faculties, and actualize their potentialities. For example, we have drives to satisfy our sensual desires, but we learn delayed gratification; we have some capacity for practical reasoning, but we improve it through education and practice; and we have a potential to become a virtuous person that we gradually actualize. Insofar as we fully actualize our potential, we develop a stable virtuous character, which leads to consistently moral behavior. In summary, morality is an expression of the virtuous character we develop as the result of ethical cultivation that actualizes our potentiality, thereby transforming our uncultivated nature at birth, which would otherwise lead to immorality. Figure 2.1 gives us a visual representation of this framework.

FIGURE 2.1

However, an important part of the rise of modern science was the rejection of the classic Aristotelian distinction between potentiality and actuality. In a famous parody by Molière (1622–73), an Aristotelian medical student explains that the reason opium puts people to sleep is that it has a virtus dormitiva, a “sleep-inducing power.”67 The suggestion is that accounts of the universe in terms of potentialities that become actualities are nothing but pretentious pseudo-explanations. Both Descartes and Hobbes deny that there is any such thing as potentiality. Descartes asserted that “a merely potential being,… properly speaking, is nothing.”68 Hobbes complained that “There is no such word as potentiality in the Scriptures, nor in any author of the Latin tongue. It is found only in School-divinity, as a word of art, or rather as a word of craft, to amaze and puzzle the laity.”69 All that exists is purely and fully actual. As we shall discuss in chapter 4, Aristotelian science is more sophisticated than it is now given credit for. Ironically, the contemporary view that physical reality is composed of mass-energy, which has the potential to assume different forms, is closer to the Aristotelian view than it is to the atomism that was the scientific orthodoxy in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.70 However, it is undeniable that early modern science achieved a revolution by attempting to explain reality quantitatively in terms of objects in motion rather than qualitatively in terms of things actualizing their potential.

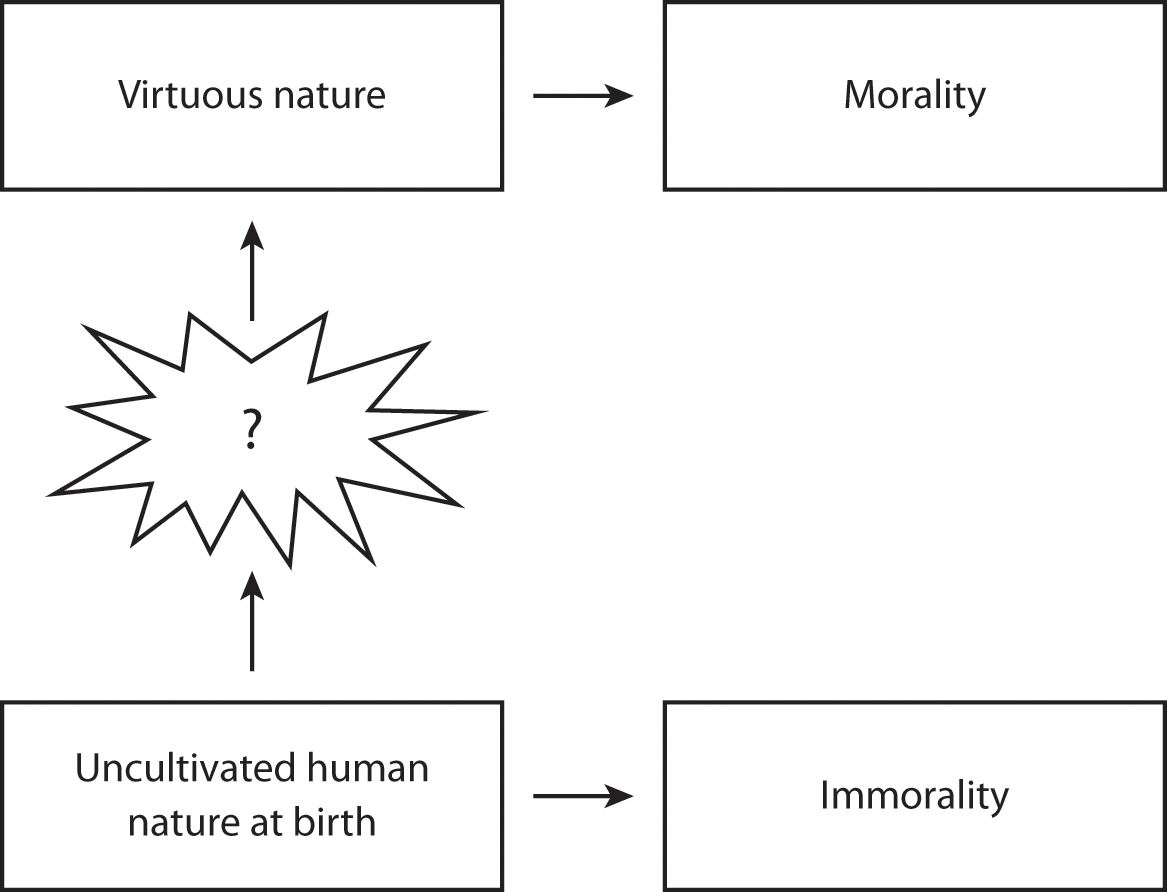

What was a positive conceptual development for natural science was disastrous for ethics, though. The stricture against discussing the actualization of a potentiality made the relationship between our innate motivations and our moral practices incoherent. The vertical dimension of ethics—what we might call the ethics of aspiration—collapsed, leaving us with an image of human nature as savage, and a moral code with no intelligible relationship to that nature. Figure 2.2 is a visual representation of the fractured framework for ethics that modernity left us with.

The political philosophy of Hobbes is an example of the desperate effort to find some rational justification for morality that appeals only to human nature at its most unrefined. Ultimately, modern ethics was led to the existentialist view that ethics is a criterion-less choice between equally unjustified ways of life (some moral and some immoral).71 Educational and spiritual practices, on this conception, are nothing but brainwashing.

Recognizing the insoluble problems that modern ethics created for itself, a host of recent Western philosophers have been leading us “back to the future” by seeking to recover and modernize the insights of the Aristotelian tradition of virtue ethics.72 However, Aristotle’s conception of ethical cultivation has serious problems of its own. Aristotle claims that “the virtues arise in us neither by nature nor against nature, but we are by nature able to acquire them, and reach our complete perfection through habit.”73 In other words: “we become just by doing just actions, temperate by doing temperate actions, brave by doing brave actions.”74 However, Aristotle thinks that the beginner in ethical cultivation does not do virtuous actions “in the way in which just or temperate people do them.”75 Specifically, the beginner does not yet love virtue for its own sake, nor does he act out of a settled state of character.76 But this leaves us with a substantial theoretical problem: If we are not naturally virtuous, how could any amount of habituation help us to develop the emotions and motivations that are distinctive of virtue? It seems that habituation can produce, at most, external behavioral compliance with virtue, rather than genuine virtue.

FIGURE 2.2

Consider an analogy. The behaviorist B. F. Skinner famously demonstrated that a pigeon can be taught to play ping-pong through conditioned response. By rewarding the pigeon with food for certain behaviors, it gradually becomes habituated to beating back a ping-pong ball thrown toward it, using its wings as paddles. This is a clear example of what habituation is like. However, it is a very unsatisfactory model of ethical cultivation. First, if we avoid stealing or lying simply because, like the pigeon, we have become habituated to certain behavior, we are not really virtuous, because we do not have the right motive. As Mengzi puts it, a virtuous person “acts out of benevolence and righteousness; he does not merely act out benevolence and righteousness.”77

Perhaps even more importantly, humans are capable of more adaptive and reflective behavior than pigeons. As Skinner demonstrated, the pigeon will keep responding to ping-pong balls the same way for the rest of its life, long after you stop rewarding it with food. However, a human can come to realize that she is no longer being rewarded for virtuous behavior, or punished for vicious behavior. As soon as virtue seems inconvenient, a person who merely behaves virtuously out of habit is easily prone to succumbing to temptation. Aristotle knows that virtue requires acting out of the right motive. However, what he lacks is a coherent explanation of how to instill those motives, given that he regards human nature as morally indifferent.

Comparative philosophers have developed a useful framework for situating Aristotle’s view of ethical cultivation in relation to various alternatives, both Anglo-European and Asian. This framework divides theories of cultivation into development, discovery, and re-formation models.78 According to re-formation models, human nature has no active disposition toward virtue, so it must be reshaped through education and behavior to acquire whatever motivations, perceptions, or dispositions that are required for virtue. Aristotle has a re-formation model, as does the ancient Confucian Xunzi. Xunzi illustrates this model of ethical cultivation with a metaphor: “Through steaming and bending, you can make wood straight as a plumb line into a wheel. And after its curve conforms to the compass, even when parched under the sun it will not become straight again, because the steaming and bending have made it a certain way.”79 Human ethical transformation is just as radical: people “are born with desires of the eyes and ears, a fondness for beautiful sights and sounds. If they follow along with these, then lasciviousness and chaos will arise.”80 However, through ethical education and socialization, a person “makes his eyes not want to see what is not right, makes his ears not want to hear what is not right, makes his mouth not want to speak what is not right, and makes his heart not want to deliberate over what is not right.”81 Re-formation models are not antirational. The person who has been successfully cultivated is in a position to see why morality is justified. However, re-formation models tend toward an authoritarian view of education, because the beginner must simply have faith that she will eventually see the why behind the what that she is being habituated into.82 The primary theoretical problem of re-formation models is that, as we have seen, they have trouble explaining how motivations like compassion, a sense of shame, and love of virtue develop out of a nature that is morally inert.

Developmental models have an easy answer to this challenge; they claim that humans innately have incipient dispositions toward virtuous feeling, cognition, and behavior. Ethical cultivation is a matter of nurturing these nascent dispositions into mature virtues. Part of what is fascinating about Mengzi is that there is no other philosopher, Chinese or European, who presents such a pristine version of a developmental model. (Rousseau is the closest Western analogue.)83 We saw earlier that Mengzi presents a thought-experiment to show that normal humans have at least an incipient tendency toward compassion (the child at the well story). Using an agricultural metaphor, Mengzi describes our innate dispositions toward virtue as “sprouts.” He claims that, in order to become fully virtuous, we have to “extend” these sprouts. There has been a vibrant debate, both in East Asia and in the West, about how precisely to understand extension. A famous dialogue between Mengzi and a king illustrates the issues.

The ruler’s subjects suffer because he taxes them excessively to pay for wars of conquest and the luxurious lifestyle that he and other aristocrats enjoy. However, Mengzi says that he knows the king is capable of being a genuinely great ruler. When the king asks Mengzi how he knows this, Mengzi relates an anecdote he had heard: “The King was sitting up in his hall. There was an ox being led past below. The King saw it and said, ‘Where is it going?’ Someone responded, ‘We are about to consecrate a bell with its blood.’ The King said, ‘Spare it. I cannot bear its frightened appearance, like an innocent going to the execution ground.’ ”84 The king confirms that the story is true but asks Mengzi what the incident has to do with being a great ruler. Mengzi replies, “In the present case your kindness is sufficient to reach birds and beasts, but the benefits do not reach the commoners. Why is this case alone different? … Hence, Your Majesty not being a genuine king is due to not acting; it is not due to not being able.”85

David Wong notes that there are three major lines of interpretation of this passage in recent Western discussions.86 (1) As we saw earlier, there were egoists in Mengzi’s era, so perhaps Mengzi simply wants the king to recognize that he is capable of acting out of compassion. This interpretation is supported to the frequent references in the discussion to the king’s capability or ability. (2) We could see Mengzi as giving the king what is a “quasi-logical” argument.87 You showed compassion for the suffering of an ox being led to slaughter (case A). However, your subjects are also suffering (case B). Since case B is relevantly similar to case A, and you showed compassion for case A, you ought to, as a matter of logical consistency, also show compassion in case B. This interpretation is supported by the fact that the word Mengzi uses for “extend” here is used by another ancient Chinese philosopher as the name for a form of inference: “ ‘Extending’ is submitting it to him on the grounds that what he does not accept is the same as what he does accept.”88 (3) Wong himself has argued persuasively for a third interpretation. Mengzi is trying to help the king to conceptualize his subjects in a new way that allows his compassion for the ox to flow to his subjects: he should see not just the ox, but each of his suffering subjects, as “like an innocent going to the execution ground.” One advantage of this interpretation is that it provides a psychologically plausible explanation of how ethical cultivation is a genuine development of preexisting motivations.

We have seen that the best metaphor to illustrate a re-formation model of ethical cultivation is carving or reshaping a recalcitrant material. In contrast, a development model goes well with the metaphor of a farmer cultivating a plant.89 Discovery models, the third category of theories of ethical cultivation, often use visual metaphors: “The Pattern of the Way simply is right in front of your eyes.”90 As this metaphor suggests, discovery models hold that humans innately have the fully formed capacities necessary for virtue. All that is needed is to exercise them. Buddhists and Neo-Confucians tend toward discovery models, because they hold that everyone is capable, at least in principle, of achieving enlightenment, which is a matter of simply discovering the way the universe actually is. Discovery models are also extremely common in the West, particularly in the modern era. The two major trends in modern Western metaethics are naturalism and intuitionism. Naturalists, like Hobbes or David Hume (1711–76), see morality as grounded in human motivations or passions. In contrast, Western intuitionists think that morality is a matter of “seeing” nonnatural moral facts. However, for both, morality is not about developing a capacity or restructuring one’s motivations, but simply discovering something, either about oneself or about the world. For example, H. A. Prichard (1871–1947) is representative of many intuitionists. He asserts that our knowledge of ethical truth is self-evident and infallible: “To put the matter generally, if we do doubt whether there is really an obligation to originate A in a situation B, the remedy lies not in any process of general thinking, but in getting face to face with a particular instance of the situation B, and then directly appreciating the obligation to originate A in that situation.”91 Notice the visual metaphor: “getting face to face with.” The only concession Prichard makes to possible disagreements is that “the appreciation of an obligation is, of course, only possible for a developed moral being, and that different degrees of development are possible.”92 We can easily imagine what sort of person Prichard, an Englishman writing at the height of the British empire, imagines to be a less “developed moral being,” and how convenient this was for imperialism.

What is striking from a comparative perspective is how remarkably primitive Western versions of discovery models are compared to their Buddhist and Neo-Confucian counterparts. This is so for at least two reasons: (1) Buddhist and Neo-Confucian versions of discovery models do not resort immediately to appeals to brute intuitions or emotions that one either has or does not have,93 and (2) they offer guidance about how to deal with cases in which you know what you should do, but find yourself strongly tempted to do something else.

Suppose I am being an inattentive father: I do not make time for my children, nor do I make an effort to share their interests, nor do I ask them persistent but good-natured questions until they finally talk to me. You tell me I really ought to take a more active role as a father. I reply that I have my own needs and projects, I already provide my children with free room and board, and lots of other parents are positively abusive, so why are you giving me a hard time? You tell me, as Prichard might, that it is a self-evident truth that I have an obligation to be a better father. Do you actually expect anything other than a middle finger in reply?

Contrast the preceding with the Neo-Confucian response to the same challenge. The Neo-Confucian would ask me “Who are you?” Any answer I give will make reference, at least implicitly, to other people, who define who I am. Consequently, if I am an inattentive father, it is not just bad for my children, because being a father is part of what defines me. Being a bad father is being a bad me. Similarly, if I am a lazy teacher, it is not bad only for my students, because being a teacher is part of who I am. To fail at being a teacher is to fail at being me. Now, I am not suggesting that the Neo-Confucian approach is guaranteed to transform immoral people into moral people. There is no magic fix for ethical nihilism. The most we can hope for from any moral theory is that it helps a few people to be a little better, and prevents a few people from becoming worse. But the Neo-Confucian challenge at least has some kind of rational traction in convincing those who may be susceptible to conversion, as opposed to the schoolmarmish finger-waving of Western intuitionism or naturalism.

In contrast to the preceding examples, suppose I already know that I should be a more attentive father or a more demanding teacher, but I give in to the temptation to fail in one or both areas. Western philosophers describe cases like these as “weakness of will”: the phenomenon in which a person knows what she ought to do but gives into temptation and does something else. This is one of the most common and familiar phenomena of our moral experience. However, it raises two substantial problems: one theoretical and one practical. The theoretical problem is to explain how moral knowledge is related to moral action in a way that makes weakness of will possible. This problem is especially pressing for any discovery model. If all there is to morality is discovering something through the exercise of an innate capacity, then it seems that the discovery of this knowledge must be both necessary and sufficient for action. The practical problem is to provide guidance to those who succumb to weakness of will about how to overcome it. Neo-Confucian philosophers have fascinating contributions to make on both issues.

Neo-Confucian debates over weakness of will typically start from an evocative passage in the canonical ancient text, the Great Learning: “What is meant by ‘making thoughts have Sincerity’ is to let there be no self-deception. It is like hating a hateful odor, or loving a lovely sight. This is called not being conflicted.”94 What is the “it” that should be “like hating a hateful odor, or loving a lovely sight”? The passage means that a person with Sincerity will hate evil like she would hate a bad odor, and love goodness like she would love a lovely sight. What is distinctive about hating a bad odor is that cognition and motivation are combined. To recognize an odor as disgusting is to be repelled by it. If I smell the milk and recognize that it has gone bad, I do not have to try to muster the motivation to avoid putting it in my coffee. My hatred of evil should manifest the same unity of cognition and motivation. If I recognize that something is evil, I should be repulsed by it, viscerally and automatically. I should not have to force myself to avoid doing evil, any more than I have to force myself to avoid drinking spoiled milk.

“Loving a lovely sight” illustrates the same point, but it requires explanation to see why. The term I am translating as “sight” here is sè. In classical Chinese (the language in which the Great Learning is written), sè can mean color or appearance,95 and some translations render it this way.96 However, it more commonly means lust, or the physical beauty that inspires lust. Thus, Confucius once complained, “I have yet to meet someone who loves Virtue as much as he loves physical beauty (sè).”97 Consequently, “loving a lovely sight” does not refer to our fondness for a particular shade of blue, or even our admiration for a beautiful sunset. It refers to being erotically attracted to physical beauty.98

So when the Great Learning tells us that we should hate evil “like hating a hateful odor” and we should love goodness “like loving a lovely sight,” it means that we are to hate evil the same way we are repulsed by a disgusting odor, and we are to love goodness the same way we are erotically drawn to physical beauty. The substantive content of these similes is the claim that our hatred of evil and our love of goodness should be simultaneously cognitive and affective. When we recognize that an odor is disgusting, we do not have to decide to be repulsed by it, or force ourselves to treat it as disgusting. To recognize an odor as disgusting (a form of perception) is to be repulsed by it (a kind of motivation). Similarly, when we recognize something as evil (perception), we should be repulsed by it (motivation) just as automatically and viscerally. The visual simile makes the same point about cognition and affect. To find someone sexually attractive is to feel drawn to that person erotically. In a parallel manner, when we recognize something as good (perception), we should be drawn toward it (motivation), without the need for any strength of will. “Sincerity” is the term used to describe this state.

Now that we understand what Sincerity is, we are in a better position to see why the Great Learning characterizes it as the absence of self-deception. On a Neo-Confucian version of a discovery model, we have an innate capacity to recognize that we are individuals who are largely defined by our relationships to others. As Wang Yangming (1472–1529) states:

Great people regard Heaven, Earth, and the myriad creatures as their own bodies. They look upon the world as one family and China as one person within it. Those who, because of the space between their own physical form and those of others, regard themselves as separate [from Heaven, Earth, and the myriad creatures] are petty persons.… How could it be that only the minds of great people are one with Heaven, Earth, and the myriad creatures? Even the minds of petty people are like this. It is only the way in which such people look at things that makes them petty. This is why, when they see a child [about to] fall into a well, they cannot avoid having a mind of alarm and compassion for the child. This is because their benevolence forms one body with the child.99

One who fully grasps that she “forms one body” with others can no more be indifferent to the suffering of her neighbor than she can be indifferent to an injury to her own limb. However, one can choose whether to attend to this knowledge or not. If one decides not to attend to his ethical knowledge, he is deceiving himself about who he really is. Hence, he is doubly engaging in self-deception: he is deceiving himself about what his self is. When we lie to ourselves in this way, we are “conflicted,” as the Great Learning says, because there is a tension between one part of ourselves, our moral nature, and another part, our selfish desires.100

Neo-Confucians in general would agree with the preceding account, both as an interpretation of the Great Learning and as a description of human moral psychology. However, there is a crucial disagreement on one detail. This ambiguity is suggested by a distinction drawn by Cheng Yi (1033–1107):

Genuine knowledge is different from common knowledge. I once met a farmer who had been mauled by a tiger. Someone reported that a tiger had just mauled someone in the area and everyone present expressed alarm. But the countenance and behavior of the farmer was different from everyone else. Even small children know that tigers can maul people and yet this is not genuine knowledge. It is only genuine knowledge if it is like that of the farmer. And so, there are people who know it is wrong to do something and yet they still do it; this is not genuine knowledge. If it were genuine knowledge, they definitely would not do it.101

The fear of the farmer who had been mauled by a tiger is another example of the sort of visceral combination of cognition and motivation that the Great Learning illustrates with the examples of a “hateful odor” and a “lovely sight.” Now, when Cheng Yi describes this as “genuine knowledge,” this suggests that those who have not been mauled by the tiger do not really know how dangerous tigers are. However, Cheng Yi does not contrast the phrase “genuine knowledge” with “fake knowledge” or “so-called knowledge,” as we might expect. He contrasts the knowledge of the farmer with “common knowledge,” which suggests that others do know that tigers are dangerous, just not as profoundly as the farmer who was mauled. So which is the right way to understand the relationship between virtuous knowledge and motivation? Should we say that those who are not motivated to do what is right do not really possess knowledge in any sense at all, or should we say that they may have a kind of knowledge, but not the deep kind of knowledge that is ideal?

Zhu Xi argues that the simile from the Great Learning must be interpreted in the light of an earlier passage in the same text that reads: “Only after knowledge has reached the ultimate do thoughts have Sincerity.”102 For Zhu Xi, this suggests a two-part process of ethical cultivation: obtaining knowledge of what is good and bad, and then making that knowledge motivationally efficacious through continual attentiveness. The beginner in cultivation will find that this attentiveness requires constant effort. When he lapses at this effort, he will succumb to weakness of will: “When people know something but their actions don’t accord with it, their knowledge is still shallow. But once they have personally experienced it, their knowledge is more enlightened, and does not have the same significance it had before.”103 This solves both the theoretical and the practical challenge that weakness of will poses. Weakness of will is possible through a failure to be attentive to the moral knowledge that we have. Our task as ethical agents is to avoid self-deception and be attentive to our moral knowledge, until doing so becomes second nature. Consequently, Zhu Xi understands the Great Learning’s similes of loving the good like loving a lovely sight and hating evil like hating a hateful odor as descriptions of the ultimate goal that each of us is working toward.

Zhu Xi’s most incisive critic was Wang Yangming. He is famous for his doctrine of the “unity of knowing and acting,” which is typically interpreted as a denial that weakness of will is possible.104 Wang states: “There never have been people who know but do not act. Those who ‘know’ but do not act simply do not yet know.”105 One of Wang’s disciples questions how this is possible: “For example, there are people who despite fully knowing that they should be filial to their parents and respectful to their elder brothers, find that they cannot be filial or respectful. From this it is clear that knowing and acting are two separate things.” Wang responds with three arguments.

First, Wang argues that ethical knowing is intrinsically connected to ethical motivation, in the same way that knowledge and motivation are connected in “loving a lovely sight” or “hating a hateful odor”:

Smelling a hateful odor is a case of knowing, while hating a hateful odor is a case of acting. As soon as one smells that hateful odor, one naturally hates it. It is not as if you first smell it and only then, intentionally, you decide to hate it. Consider the case of a person with a stuffed-up nose. Even if he sees a malodorous object right in front of him, the smell does not reach him, and so he does not hate it. This is simply not to know the hateful odor. The same is true when one says that someone knows filial piety or brotherly respect. That person must already have acted with filial piety or brotherly respect before one can say he knows them.106

For Wang, the simile from the Great Learning does not describe the goal of cultivation, in which ethical knowledge and motivation are fully unified after years of effort; instead, it describes what genuine ethical knowledge is like from the very start. In the vocabulary of Western ethics, Wang is a motivational internalist, who holds that to know the good is intrinsically to be motivated to pursue it.107

Wang’s second argument for the unity of knowing and acting is that merely verbal assent is insufficient to demonstrate knowledge: “One cannot say that he knows filial piety or brotherly respect simply because he knows how to say something filial or brotherly. Knowing pain offers another good example. One must have experienced pain oneself in order to know pain. Similarly, one must have experienced cold oneself in order to know cold, and one must have experienced hunger oneself in order to know hunger.”108 To understand the important epistemological and linguistic point Wang is making here, consider a variation on a classic example from Western philosophy. Imagine a hypothetical individual, “Mary,” who is forced to perceive the world through a black and white television monitor. She becomes a brilliant neuroscientist specializing in vision, and eventually knows everything there is to know about the physics and neurology of color experiences. However, suppose she is finally released from her bondage to the black and white television monitor and can go and see the world as it is. Now she will learn something new. She will finally know what phenomenal colors are like. Previously, Mary knew more about color experiences than anyone else, but she did not know what phenomenal colors are.109 Similarly, Wang says, you might know a lot about pain, hunger, feeling cold, and goodness, but you do not know pain, hunger, feeling cold, or goodness itself unless you have the right experience. One significant difference between Wang’s example and that of Mary is that color experiences are not intrinsically motivating. It does seem plausible, though, that some experiences (among them pain) are intrinsically motivating.

Wang’s disciple objects that we talk about knowing and acting separately, and that this verbal distinction is valuable because it reflects the fact that there are two distinct aspects to moral cultivation. Wang acknowledges that it can be useful for practical purposes to verbally distinguish between knowing and acting:

there is a type of person in the world who foolishly acts upon impulse without engaging in the slightest thought or reflection. Because they always act blindly and recklessly, it is necessary to talk to them about knowing. There is also a type of person who is vague and irresolute; they engage in speculation while suspended in a vacuum and are unwilling to apply themselves to any concrete actions. Because they only grope at shadows and grab at echoes, it is necessary to talk to them about acting.110

However, Wang argues that verbally distinguishing “knowing” and “acting” is consistent with recognizing that they are two aspects of one unified activity: “I have said that knowing is the intent of acting and that acting is the work of knowing and that knowing is the beginning of acting and acting is the completion of knowing. Once one understands this, then if one talks about knowing [the idea of] acting is already present, or if one talks about acting, [the idea] of knowing is already present.”111 We might say that knowing and acting are like the concave and the convex sides of a curved line: conceptually but not metaphysically distinguishable.

Reviewing Wang’s arguments, we can see why David S. Nivison remarked, “There are pages in Wang, sometimes, that could almost make acceptable brief notes in contemporary philosophy journals like Analysis.”112 However, it is important to recognize that Wang’s point is not purely theoretical. What he is concerned about is the phenomenon of people who

separate knowing and acting into two distinct tasks to perform and think that one must first know and only then can one act. They say, “Now, I will perform the task of knowing, by studying and learning. Once I have attained real knowledge, I then will pursue the task of acting.” And so, till the end of their days, they never act, and till the end of their days, they never know. This is not a minor malady, nor did it arrive just yesterday. My current teaching regarding the unity of knowing and acting is a medicine directed precisely at this disease.113

Wang has in mind the followers of Zhu Xi, but his point has contemporary relevance. Eric Schwitzgebel has done empirical research on the relationship between studying or teaching ethics and actual ethical behavior. He acknowledges that the data is limited, but so far he has been unable to find any positive correlation between the theoretical study of ethics and being ethical.114 Wang would argue that this proves his point: the abstract and theoretical study of ethics will not make you a better person. However, Wang would insist that what is wrong with Western ethics is not that it tries to make humans better people, but that it does not try in the right ways. If we have any interest in our courses in ethics and political philosophy making a difference, it is worth looking at what else thinkers like Mengzi, the Buddhists, Zhu Xi, and Wang Yangming have to say on this topic.

Just to give a teaser: Confucians stress that, to provide a foundation for ethical development, it is the responsibility of government to make sure that the people’s basic physical needs are met (for food, for freedom from fear, and for the possibility for communal life), that everyone gets an education that both teaches them basic skills and socializes them to be benevolent and have integrity, and that everyone who can benefit from advanced education has the opportunity to receive it (regardless of social class). Regarding the structure of ethical education, Confucius himself says, “If you learn without thinking about what you have learned, you will be lost. If you think without learning, however, you will fall into danger.”115 As Philip J. Ivanhoe notes, later Confucians agree with this saying, but argue vociferously about the relative emphasis to give to learning from classic texts and teachers as opposed to thinking independently.116 As you might guess, philosophers with a discovery model of cultivation like Wang Yangming tend to emphasize thinking, while those with a re-formation model like Xunzi put more emphasis on learning.