My reading of Edgar Allan Poe’s crime fiction locates the subject’s fissures in the fraught relationship to animal representation. Exploring the tension between alterity and identity, his fiction develops a hermeneutics that reads the “symbolic order” in relation to the bodily, the abject, and the animalized. By affording that bodily register its own legibility, he develops grounds for understanding the mechanisms by which subjectivity produces itself via an engagement with the beastly and provides a means for engaging critically with that production. In this chapter and the next, I take up an issue I raised in the previous chapter’s discussion of “The Black Cat”: how the scene of bestiality gets rewritten as one of “puppy love” with the rise of sentimentalism in the nineteenth century and its permutations in the twentieth century. I focus in particular on the role that theories of childhood education play for understandings of subjectivity and on the way in which infantilization—as a practice, as a strategy—maps animal relations onto psychological and commoditized object relations.

Framing my discussion of Emily Dickinson in relation to post-structuralist affect theory, I demonstrate how she might advance our understanding of liberal subjectivity beyond its current parameters.1 Post-structuralist affect theory and liberalism open a space for radical alterity, but they too easily foreclose that space by reinscribing affect in an ontologically defined frame that distinguishes human beings from animals. At stake in that foreclosure is the production of a particular notion of subjectivity as a subjectivity marked by an individuality independent of others and clearly demarcated by the separation of reasoning from embodiment. Looking at animals gives us a different account of the subject, as relational and contingent on an alterity that cannot easily be reinscribed in the registers of either abstract rationality or embodied affectivity. Through Dickinson’s experimentations with animal representations, we see new possibilities for subjectivity and poetry emerge in her work. Engaging with the pedagogical and literary models that became a staple of childhood education in the nineteenth century, Emily Dickinson stretches our understanding of literary representation beyond symbolization by rethinking orthography as a confrontation with literal animals. Deliberately invoking Lockean pedagogy, she adopts the persona of a child. That persona enables her to reject the telos of Lockean pedagogy—the separation of the human being from the animal. Placing herself in a position of ambiguity, where the human and the animal are conjoined and not yet separated, Dickinson engages the parameters of liberal subject formation to envision an alternative.

The Liberal Imagination and Post-structuralist Affect Theory

In 1950, Lionel Trilling published a collection of his essays under the title The Liberal Imagination. In two essays that frame his reflections on topics ranging across nineteenth- and twentieth-century literature, he outlines his definition of liberalism as well as his understanding of the role that literary criticism plays in bringing that liberalism to fruition. For Trilling, liberalism’s potential and its shortfalls hinge on its ability to engage both ideas and emotions (or sentiments, which he uses as a synonym) and to keep both in dynamic relation to one another. For models of how such balance might work, he repeatedly turns to examples of nineteenth-century writers for whom the stakes of balancing ideas and emotions—and of engaging with literature—were political. By politics, Trilling means the “wide sense of the word”—that is, “the politics of culture, the organization of human life toward some end or other, toward the modification of sentiments, which is to say the quality of human life.” Although this statement echoes the scope and vagueness of his earlier claim that liberalism is “a large tendency rather than a concise body of doctrine,” it also makes a programmatic claim about literary criticism itself: that its domain is properly the political, where the political is understood as emerging at the intersection of emotions and ideas.2

Trilling’s assessment of the political has met—as has the larger postwar discourse celebrating liberalism—with a wide range of appropriations and dismissals over the years since the volume’s publication.3 Without positing a causal relationship between Trilling’s work and later scholarly developments, we might nevertheless read his remarks on the role of the emotions and their connections to politics as a prescient commentary on the engagement that the scholarly field of nineteenth-century American literary studies has with figuring out how sentiment, emotion, intimacy, and affect produce and unravel subjects, liberal and otherwise.4 The methodologies of this enterprise have been eclectically borrowed from feminism, gender studies, queer studies, post-structuralism, new historicism, and cultural studies, but scholars have recently begun to identify this field of inquiry as its own theoretical school and to speak of “the affective turn” in American literary studies, as the title of a 2007 collection of essays on the topic proclaims.5

Writing in the preface to this volume, Michael Hardt argues that “affects refer equally to the body and the mind” and place reason and passion “together on a continuum.” As a consequence, affect studies produces “a new ontology of the human or, rather, an ontology of the human that is constantly open and renewed.”6 Hardt’s comment begs the question what anchors that new ontology in relation to “the human.” Although his claim echoes Trilling’s emphasis on the role that emotions play for the construction of “the nature of the human mind,” “the organization of human life,” and “the quality of human life,”7 Hardt’s concluding reference to a new ontology opens a space for inquiry that presses us beyond the explicitly humanist framework of liberal subject formation outlined by Trilling.

It is this ontological openness that I want to explore in order to understand how the affective relationship between human beings and animals founds and confounds the parameters of liberal subject formation. Beginning with an overview of what affect studies might teach us about nonhuman ontologies, I then situate key concerns of this current scholarly undertaking in relation to the historical origins of liberal humanism in John Locke’s educational philosophy. Tracing the impact of his pedagogy on American literature, I demonstrate how liberal subject formation emerges from the relationship with animals. That relationship plays a key role in the development of literacy, which is the very staple of liberal subjectivity. As I demonstrate in my case study of Emily Dickinson, animals literally disrupt and figuratively challenge the parameters of representation on which liberal subjectivity is founded.

Although many scholars working in affect theory remain dedicated to an explicitly humanist enterprise, the logical outcome of their work opens the possibility for thinking about subjectivity in a more expansive register than one limited to existing notions of the human. In Feeling in Theory, Rei Terada argues that we need to rethink emotion as “nonsubjective.” She explains that emotion is often cast “as a basis for naturalized social or moral consensus,” but she also draws our attention to the fact that “such a gesture depends on an even more fundamental one that casts emotion as proof of the human subject.” Terada wants to “free a credible concept of emotion from a less credible scheme of subjectivity … the effect of this exploration is to suggest that we would have no emotions if we were subjects.”8 She takes issue with how affect theory is willing to grant that “even nonsubjects have affects” but then distinguishes emotions as the realm of the human.9 Terada rejects this differentiation and rewrites the critical nomenclature of affect theory so that it includes not only the psychological experiences of human beings, but also the physiological sensations of all living creatures. Terada’s reconceptualization usefully eliminates one of the many binaries that result from the dichotomy between “the human” and “the animal”: the dichotomy between emotion and affect.

The conflation of emotion and affect hinges on the fact that for Terada, “emotion is an interpretive act”: “our emotions emerge only through acts of interpretation and identification by means of which we feel for others…. We are not ourselves without representations that mediate us, and it is through those representations that emotions get felt.”10 By refusing to specify that those “others” must always already be human, Terada opens the terrain that nineteenth-century literature tried to negotiate in imagining how affective bonds with animals had a constitutive effect on subjectivity. She also draws our attention to the role that representation plays for the process of affective engagement and subject formation. She argues that affect studies arose out of a reaction against “the things [that] ‘linguistic’ theories” supposedly cannot do, which is to “explain ‘effects’ of thinking, willing, and … feeling.”11 Terada’s work brokers a relationship between language and feeling that does not subsume one to the other but instead shows their complicated, refracted connections to each other.

What we mean by representation and by the “linguistic” will get reshaped in the process of such an inquiry. Lauren Berlant argues in her landmark special issue on intimacy for Critical Inquiry that “to intimate is to communicate with the sparest of signs and gestures, and at its root intimacy has the quality of eloquence and brevity.” By this account, intimacy functions as a relay between the body and representation, where both operate as discursive registers that we can understand only in relation to each other. How that understanding develops hinges on a particular set of “pedagogies.” Intersubjectivity gets produced across uneven terrain, leading Berlant to ask: “How can we think about the ways attachments make people public, producing trans-personal identities and subjectivities, when those attachments come from within spaces as varied as those of domestic intimacy, state policy, and mass-mediated experiences of intensely disruptive crises?” For her, the answer lies in finding ways of reframing intimacy that engage and disable “a prevalent U.S. discourse on the proper relation between public and private, spaces traditionally associated with the gendered division of labor.” The stakes of such an enterprise are high because “liberal society was founded on the migration of intimacy expectations between the public and the domestic.” Berlant sees both a normative and a liberatory potential in reframing how we understand “liberal society”: “While the fantasies associated with intimacy usually end up occupying the space of convention, in practice the drive toward it is a kind of wild thing that is not necessarily organized that way, or any way.” Crucial for this enterprise of approaching the “wild thing” remains an inquiry into the linguistic: Berlant writes that it is “the linguistic instability in which fantasy is couched [that] leads to an inevitable failure to stabilize desire in identity.” Reading that linguistic instability calls “for transformative analyses of the rhetorical and material conditions that enable hegemonic fantasies to thrive in the minds and on the bodies of subjects”; that is, they call for an engagement with the conventions of affect and with strategies for exploiting those conventions for the purpose of transforming them.12

Although this attention to the representational and the linguistic might seem to return us to the domain of the human, I want to suggest that it instead presents us with the possibility for reading the relationship with animals as integral to structures of a reconfigured subjectivity. Christopher Peterson has formulated the question at which we arrive: “How might our relationship to the ‘radical alterity’ of nonhuman animals contest, instead of simply reaffirm, our normative conceptions of intimacy? What might the alterity of nonhuman animals have to teach us about the alterity of those human animals with whom we imagine the most intimate kinship?”13 I want to explore the affective relationship between human beings and animals and examine how that relationship is worked out in animal representations.

Locke, Animals, and the Formation of American Literature

These relationships are central to the text—and especially to its reception—credited with founding our understanding of liberal subject formation: John Locke’s Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693). This text has variously been recognized as inaugurating the fields of pedagogy, child psychology, children’s literature, the sentimental novel, and American literature as such; it was “probably even more widely read and circulated than the Two Treatises of Government,”14 and it “served in its various popularized forms as perhaps the most significant text of the Anglo-American Enlightenment.”15 Responding to a friend’s request for advice on how to rear his son, Locke eschews physical punishment and makes affect central to a pedagogy that accounts equally for children’s physical and mental well-being. What interests me here is the special status he affords animals in the didactic enterprise of enabling children to develop their capacities: the affective relationship to animals forms the nexus between the body and mind that is requisite for liberal subject formation, but it also challenges the very parameters of that subject formation.

At first glance, Locke’s reflections seem to distinguish human beings as rational creatures from other beings who are driven by appetites and emotions. He emphasizes the importance not only of teaching children how to moderate and control their emotions but advocates modeling such control in disciplining them: “When I say therefore, that they [children] must be treated as Rational Creatures, I mean that you should make them sensible by the Mildness of your Carriage, and the Composure even in your Correction of them, that what you do is reasonable in you, and useful and necessary for them.”16 Locke defines children as “Rational Creatures” who recognize “what is reasonable” in their parents and who in turn come to act reasonably by the example set them. However, this emphasis on reason depends on the ability to make children “sensible” to the kinds of emotions their parents exercise when they demonstrate “mildness” and “composure” in their reactions. Children’s ability to learn from their parents hinges on their ability to develop a kind of empathy with their parents: they recognize their own ability to reason in seeing what is “reasonable in” their parents and in turn reflect that reasonableness back on themselves by recognizing it in utilitarian terms as what is “useful and necessary for them.” In the encounter with their parents, they come to recognize their own interests and to develop a sense of themselves as interest-bearing subjects. That recognition of their interests precedes their entry into full legal personhood and their social recognition as legal subjects.

Although children learn from watching their parents’ reasonable behavior, their mode of education is practical, not abstract. Locke insists that in all aspects of learning “children are not to be taught by Rules, which will be always slipping out of their Memories. What you think necessary for them to do, settle in them by an indispensible Practice, as often as the Occasion returns; and if it be possible, make Occasions.”17 For Locke, learning occurred experientially, not abstractly.18 Eschewing abstract “rules,” he argues that memory formation occurs through practice and repetition. This practical education depends on children’s experience of other people’s actions but also involves guiding their own actions.19 Locke sets up an analogy by which parents’ treatment of their children mirrors children’s treatment of animals; this analogy functions as a literal chain of creaturely hierarchy by which the more powerful exercise control over the less powerful and, as I explain more fully later, as a chain of metaphoric substitutions by which each component of the chain represents the other.

At stake in these carefully calibrated relationships is children’s initiation into proper modes of governance. Pointing out that “children love Liberty,” he says, “I now tell you, they love something more; and that is Dominion: And this is the first Original of most vicious Habits, that are ordinary and natural.”20 Here he infuses his reflections with a political vocabulary, in which the desirable “love” of liberty fights against an undesirable “love” of dominion. Insisting that affects differ qualitatively, Locke also indicates that his key pedagogical strategy—practice—can produce results conducive or adverse to good social order. In using the explicitly biblical language of “dominion” and an invocation of “Original” sin (“vicious Habits”), he is working out what role “natural” inclinations play in forming children’s political desires. For him, the “natural” here is the product of habits, not their origin.21

The relationship with animals is crucial to the process of redirecting children’s love for dominion into a proper love of liberty that hinges on the mutual recognition of subjects’ interests. In his advocacy of humane practices, Locke initially focuses on human beings themselves, not on their animal victims. He explains that “the Custom of Tormenting and Killing of Beasts, will, by Degrees, harden their [children’s] Minds even towards Men; and they who delight in the Suffering and Destruction of inferiour Creatures, will not be apt to be very compassionate, or benign to those of their own kind. Our Practice takes Notice of this in the Exclusion of Butchers from Juries of Life and Death.”22 Locke argues that humane conduct to animals ensures that human beings will treat each other with compassion. In repeatedly exercising one kind of affect, delight in the suffering of animals, children lose the ability to engage in the bonds of sympathy that underlie civic society: like butchers, they become unfit to enter into the juridical process, which is based on a balance between reason and compassion. Even though Locke’s emphasis is on the way human beings treat each other, his argument depends on the substitution of animals for human beings: being cruel to animals results in being cruel to other human beings; the two are not separate from one another but, on the contrary, lie on a continuum. The ability to identify affectively with other human beings and to enter into social and legal relations with them depends on an ability to exercise proper compassion to animals.

Kindness to animals produces “good Nature” in children. That good nature expresses itself not only in reasoned relationships, but in emotional and physical ones: Locke emphasizes that the children should be “tender”—that is, feeling, loving, caring—to all “sensible” creatures, or all beings who have the capacity for physical and emotional feeling. Locke spells out what he means by “sensible” when he reproaches children for putting “any thing in Pain, that is capable of it.”23 At this point in his reflections, animals are no longer simply stand-ins for human beings; their own capacity for feeling has become important. Yet recognizing that importance defies social conventions, which Locke critiques in comments that pave the way for anticruelty and animal welfare activism. For Locke, the enjoyment of another creature’s pain is “a foreign and introduced Disposition, an Habit borrowed from Custom and Conversation. People teach Children to strike, and laugh, when they hurt, or see harm come to others … By these Steps unnatural Cruelty is planted in us; and what Humanity abhors, Custom reconciles and recommends to us, by laying it in the way to Honours. Thus, by Fashion and Opinion, that comes to be a Pleasure, which in it self neither is, nor can be any. This ought carefully to be watched, and early remedied, so as to settle and cherish the contrary, and more natural Temper of Benignity and Compassion in the room of it.”24 Pitting humanity against custom, Locke comes close to abandoning his own precept that nature is the product and not the origin of education; he entertains the notion that human beings are innately good and that cruelty is the “unnatural” result of habits “planted in us.” Yet he retreats from this approach by casting natural as a comparative term: he advocates establishing a “more natural Temper” in children that runs contrary to social habits and returns children to a sense of “benignity.” The relationship with animals has the capacity to “instill Sentiments of Humanity, and to keep them lively in young Folks.”25 Humanity itself has here become a “sentiment,” one that hinges on compassion for animals. Far from functioning as an ontological category, humanity is the product of an educational process that relies on the relationship to animals to elicit and direct emotions; in other words, the liberal subject emerges through its properly affective engagement with animals.

Locke’s work produces two connected strands in its writing on animals: it engages with the corporeal relationship between human beings and animals, and it inscribes that relationship at and as the core of representation. Turning to the topic of how children learn to read, Locke suggests that adults ought “to teach Children the Alphabet by playing.” Once that basic literacy has been accomplished, adults should provide a child with “some easy pleasant Book suited to his Capacity,” for which Locke has a specific recommendation: “I think Aesop’s Fables the best, which being Stories apt to delight and entertain a Child, and yet afford useful Reflections to a grown Man.” Locke’s recommendation takes on an even more specific tone when he suggests that “if his Aesop has Pictures in it, it will entertain him much the better, and encourage him to read, when it carries the increase of Knowledge with it. For such visible Objects Children hear talked of in vain, and without any satisfaction, whilst they have no Ideas of them; those Ideas being not to be had from Sounds; but from the Things themselves, or their Pictures. And therefore I think, as soon as he begins to spell, as many Pictures of Animals should be got him, as can be found, with the printed names to them, which at the same time will invite him to read, and afford him Matter of Enquiry.”26 Animals come to occupy a central position in the child’s—and by extension the man’s—literacy. Children are not able to translate “sounds” into a connection with “ideas”; they arrive at those ideas through a relationship to “Things themselves, or their Pictures.” Things and pictures take on an interchangeable relationship that makes animals figuratively and literally present for children as they develop their literacy skills.

These claims establish two important trajectories for people’s engagements with animals subsequent to Locke. First, they blur the distinction between human beings and animals; animals themselves increasingly become subjects. Instead of seeing animals as a vehicle for human relationships, the animals themselves begin to matter in their own right. Second, these engagements give rise to writing and reading practices centered on (animal) bodies. As scholars such as Karen Sánchez-Eppler have pointed out, sentimentalism makes “reading … a bodily act.”27 Reading becomes an act of encountering the bodies of others and of needing to come to terms with their proximity and alterity. This encounter with animal bodies challenges us to expand our understanding of the work sentimentalism can do for cross-species relations. Elizabeth Dillon has explained that sentimentalism creates a “shared humanity” because it links individuals via their capacity “to feel deeply” and “to suffer.”28 What happens when sentimentalism does not automatically link back to humanity but instead creates connections with animals that press us beyond the human and humanist pale?

This question is far from peripheral to our understanding of nineteenth-century literature. As Gillian Brown and others have documented, “Americans knew Locke’s ideas not only from these books, but also, and more profoundly, from the popular pedagogical modes and texts inspired by Locke’s thought. Whether or not they knew Locke’s writings, early Americans assimilated Lockean liberalism as they grew up.”29 In Locke’s writing, the relationship between human beings and animals provides a model for initiating and integrating children into the social fabric as liberal subjects. But in the hands of a writer such as Emily Dickinson, the relationship to animals also provides modes for resisting social orders and imagining alternative subjectivities. In the next section, I situate Dickinson’s work in the context of the nineteenth-century engagement with Lockean notions of subject formation.30 Dickinson’s case is interesting to me because she successfully channels a larger social discourse and in the process questions its assumptions and methodologies. She reevaluates the relationship between physical bodies and abstract representation and is particularly attentive to the role that gender plays in the formation of subjectivity. Demonstrating a link between the social construction of species and the social construction of gender, she explores how relationships to animals can unsettle both constructions and can generate alternative forms of representation.

Emily Dickinson and the Discontents of Liberal Subjectivity

Carlo died—

E. Dickinson

Would you instruct me now?31

In 1866, Emily Dickinson ended a lapse of eighteen months in her correspondence with Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson by sending him three lines that connect the major concerns of her work: death, subjectivity, and the conditions of knowledge. When Higginson later published these lines among Dickinson’s letters, he explained that the poet would on occasion include “an announcement of some event, vast to her small sphere as this,” the death of her dog, who had been her companion for sixteen years. In feminizing and privatizing Dickinson’s loss and measuring it biographically by the “small sphere” of her life, Higginson sets aside this particular poet’s ability to “wade grief” and situates Dickinson’s letter within the sentimental culture of pet keeping that had transfigured a predominantly agricultural practice (as noted in the introduction, the word pet initially referred to a lamb) into a staple of genteel domesticity and bourgeois subjectivity.32 Far from participating uncritically in the roles and relationships Higginson projects onto her, Dickinson interrogates the formation and gendering of sentimental subjectivity by placing “Carlo died” in relation to the other two lines—the signature and the call for instruction. “E. Dickinson” refers ambiguously to Emily or to her father, Edward Dickinson. The signature pluralizes the subject; it doubles and ultimately obscures “E.’s” gender.33 This ambiguous subject hinges on the animal’s death as a scene of pedagogy: it stands in the liminal space between the announcement of Carlo’s death and the request “Would you instruct me now?”

It is easy to overlook this question’s relevance to and bearing on Carlo’s death because the call for instruction is a constant refrain in Dickinson’s correspondence with Higginson. If we trace that refrain, it becomes apparent that Dickinson consistently links the scene of pedagogy with the formation of subjectivity via the trope of the animal. In her introductory letter to Higginson, she asked him “to say if my Verse is alive? … Should you think it breathed—and had you the leisure to tell me, I should feel quick gratitude.”34 Dickinson portrays a liveness that animates her poetry and whose breathing produces the poet’s own affective “quick[ening].” She more fully develops these connections when she responds to Higginson’s request for a self-description: “You ask of my Companions Hills—Sir—and the Sundown—and a Dog—large as myself, that my Father bought me—They are better than Beings—because they know—but do not tell—and the noise in the Pool, at Noon—excels my Piano.”35 This composite portrait blends the animate and the inanimate, the object with the subject, to unhinge their epistemological meanings and ontological differentiation. But what exactly is the surplus that makes her “Companions … better than Beings”? In using the term companion, Dickinson draws on the same vocabulary that informs Donna Haraway’s reading of human beings and dogs as “companion species” that stand “in obligatory, constitutive, historical, protean relationship” to one another.36 Like Haraway, who argues that animals “are not about oneself…. They are not a projection,”37 Dickinson abandons the normative reference to human subjectivity by making the dog “better than Beings” and placing the implied adjective of “Beings,” human, under erasure.

That erasure should also give us pause from mapping Dickinson too readily in relation to Haraway and the growing number of feminist scholars who believe animal studies in general and “dog writing” in particular “to be a branch of feminist theory.”38 Dickinson’s terse prose cautions us about patriarchy’s vested interest in sentimentalizing women’s relationship with animals and in making the way women perform their gender contingent on the way they perform their species. That contingency is exemplified in Thomas Wentworth Higginson’s 1887 article “Women and Men: Children and Animals,” where he insists that “the care given by the young girl [to her pet] was simply the anticipated tenderness of a mother for her child.”39 As with Locke’s metaphors, casting the girl’s relationship to the dog as analogous to the mother’s relationship with her child infantilizes women (they are like girls), anthropomorphizes animals (pets are like children), and animalizes children (children are like pets).

Early reviews picked up on Dickinson’s interest in using infantilization as a strategy for exploring these oddly mutable subject positions; they described Dickinson’s poetry as showing “the insight of the civilized adult combined with the simplicity of the savage child.”40 In describing the dog as something that “my Father bought me,” Dickinson casts herself in the role of her parent’s child—that is, in the role of the subject to be formed by Lockean education. She draws attention to the objectifying structures that underlie the sentimental association of women and animals by pointing to Carlo’s status as a commodity and gift. Her double reference to “myself” and “me” inscribes her subjectivity in this act of gift giving and places her in the precarious position that women share with fetish objects and anthropomorphized subjects: by dropping the preposition for in “bought me” and establishing a simile between the “dog” and “myself,” Dickinson allows for the double possibility that Carlo and “me” were the objects her father “bought me.” With this odd slippage between the dog and the daughter, the gift and the recipient, she suggests that women, children, and animals mediate the relationship between the object and the subject; they establish the boundaries along which human subject formation in distinction from nature becomes possible.

In staging her relationship to her dog, Dickinson performs and undercuts these differentiations. Although her relationship with the dog her father bought her infantilizes her, Carlo allows her small stature to appear “large.”41 By drawing on the animal as a trope-reversing trope, Dickinson deconstructs the very processes and parameters of gendered subject formation. The name “Carlo” signifies the central role that dogs play in the literary construction of subjectivity. Dickinson named Carlo after two literary characters, St. John River’s dog in Jane Eyre and Ik Marvell’s dog in Reveries of a Bachelor.42 The name is thus not only a referent for a real dog, but also a referent for the fictional representation of animals.

Fictional representations of animals have been popular in English-language literature since the Middle Ages: Caxton published his translation of Aesop’s Fables in 1484, and Locke’s suggestion that this was the “only Book almost” suited to children’s education speaks to the work’s popularity. Moreover, Locke’s recommendation itself initiated an interest in integrating animal characters into the children’s literature that emerged as a new genre in response to his writings.43 Locke’s reflections on animals’ didactic importance fundamentally changed pedagogical strategies for educating children to become liberal subjects. In the late eighteenth century, animals began to take on a central function as animals in the instruction of children. Even fables were enlisted in this new endeavor, as the subtitle of Sarah Trimmer’s vastly popular Fabulous Histories (1786) illustrates: the book was “designed for the instruction of children respecting their treatment of animals.”44 In fact, animals played an increasingly important role not just in moral education, but in children’s initiation into language itself—as indicated by the example of Aesop’s Fables in French: With a Description of Fifty Animals Mentioned Therein and a French and English Dictionary of the Words Contained in the Work (1852).45

Emily Dickinson’s Carlo participated in this educational reform. In 1863, her uncle by marriage, Asa Bullard, published a book entitled Dog Stories that prominently featured a dog named Carlo. As the secretary and general agent of the Massachusetts Sabbath School Society, Bullard edited the Sabbath School Visitor, to which Edward Dickinson subscribed for his children beginning in 1837, and Bullard numbered among the relatives Dickinson knew best because she stayed with him and her aunt Lucretia when she visited Boston for eye surgery. In sketches that restage the constant warfare between his dog-loving niece Emily and her cat-loving sister Lavinia, Bullard depicts scenes that amount to Christian allegory: in his portrayal of Carlo, the “Faithful Dog” cannot be lured away by temptation to abandon his master’s charge. In Bullard’s account of “Little Charlie and Fido,” the dog “appears to know about as much as some boys; and he is a great deal more ready than some are to do a favor, and more thankful for any act of kindness shown him.” Indeed, dogs come to stand in for knowledge itself when Bullard describes how Carlo eventually clears a ditch because his master’s voice has encouraged him: “Many children find their school duties hard to accomplish. Let the kind word of encouragement be given, and many of them, like the little dog Carlo, will surmount the difficulty and find their future course a joyous one.”46 Animals inhabit the same didactic position as the texts that represent them, and serve as mediators for liberal subjectivity: Bullard’s admonition ties the “kind word” and animals to each other as jointly enabling scholarly accomplishments; it promises that the pursuit of learning will find “joyous” fulfillment in a “future course.”

What situates Bullard’s book in a larger context of nineteenth-century children’s literature is that it does not just portray the animals’ behavior as exemplary; it uses animals to teach children kindness, and draws on versification to do so:

I’ll never hurt my little dog,

But stroke and pat his head;

I like to see him wag his tail,

I like to see him fed.

The coward wretch whose hand and heart

Can bear to torture aught below,

Is ever first to quail and start

From slightest pain or equal foe.47

These stories operate on the basis of what I call “didactic ontology,” by which I mean the practice of teaching children how to be human by teaching them how to be humane. Animals take on a double role in this didactic literature: animals stand in for children—their behavior models for the child how to behave, and they are important as animals whose vulnerability and exposure to potential cruelty teaches children to be kind. Children relate to animals through a double sense of identification and separation: because the animal is like them, they are asked to extend kindness, but the kindness they extend makes them human stewards of animals and marks their separation from them. Animals remain the trace of children’s own presocial being and become the supplement to liberal subjectivity. This relationship depends on the use of simile; in the passage I quoted earlier, Bullard writes that children should be aided in their schoolwork by the “kind word of encouragement,” which will allow “many of them, like the little dog Carlo” to “surmount the difficulty.” Whereas metaphor (as I discuss later) conflates the two positions that ontology wants to separate, the human and the animal, simile keeps them recognizably separate: it gestures at a tertium comparationis, a third entity that enables the comparison while maintaining the differentiation between the entities that are being compared. In this case, that third entity is the “kind word,” which functions not only to encourage children but also to inscribe them in a linguistic structure that separates them from animals: it integrates them into the pedagogical setting and disciplines them into fulfilling their “school duties.”

Dickinson reinvents this use of simile by making language itself the locus of an animal presence that does not separate human beings and animals, but rather integrates them. Dickinson’s portrayal of her dog as “better than [human] Beings” echoes a key assertion of this literature: that the virtues of animals reflect on the moral shortcomings of human beings. But Dickinson undercuts that lesson by dropping the word human and confounding the parameters of didactic ontology where the human is the teleological outcome. Her insistence that her companions “know—but do not tell” indicates her resistance to the didactic interpretation of the animal. Dickinson silences the pedagogical voice and instead gives play to “the noise in the Pool, at Noon” which functions as a form of knowledge that does not express itself in telling, in human language, but in a musical mode of expression that “excels my Piano” in that, as “noise,” it is an experiential and disordered form of natural expression.48

Dickinson stages and suspends the child’s entry into an adult symbolic order that turns animals into dead metaphors by disavowing and historicizing their presence. Using the same metric form and rhyme pattern as Bullard, she performs a formal parody of this kind of animal writing in a poem from 1871:

A little Dog that wags his tail

And knows no other joy

Of such a little Dog am I

Reminded by a Boy

Who gambols all the living Day

Without an earthly cause

Because he is a little Boy

I honestly suppose—

The Cat that in the Corner dwells

Her martial Day forgot

The Mouse but a Tradition now

Of her desireless Lot

Another class remind me

Who neither please nor play

But not to make a “bit of noise”

Beseech each little Boy—49

Dickinson begins the poem sounding like the didactic literature she is imitating: she suggests that the boy is like the dog, but the moral lesson we expect to follow—that such likeness obliges him to a kindness that ultimately separates him from the dog—is missing. Indeed, if we look closely, the dog is not a stand-in for the boy; on the contrary, the boy is a stand-in for the dog in Dickinson’s reversal of the trope. Dickinson’s boy is allowed to inhabit a relationship to the dog that resists their didactic separation from one another. This resistance to didactic separation deepens when we contextualize this poem with its private circulation. In letters to her family, Dickinson habitually referred to herself as a boy—for instance, when she wrote to her nephew Ned: “Mother told me, when I was a boy, that I must turn over a new leaf. I call that the foliage admonition. Shall I commend it to you?”50 Turning an admonition into a question, Dickinson here, as in the poem, undercuts the didactic message that “another class” wants to impart. Indeed, that resistance to “admonition” is a theme throughout her correspondence with Ned. In the letter that included an abridged version of this poem, Dickinson offset its purported didacticism by adding a postscript: “P.S.—Grandma characteristically hopes Neddy will be a good boy. Obtuse ambition of Grandma’s!”51 Far from reprimanding the boy, she allies herself with him against those adults who would silence him. Unlike the cat’s dead “Tradition” of a “martial Day” that stands in opposition to the boy’s “living Day,” the boy is free to “know no other joy” than the expression of his own pleasure.

But in being asked “not to make a ‘bit of noise,’” the boy is soon deprived of the ability to participate in “the noise in the Pool, at Noon”—that is, in the natural forms of expression that provide an alternative discourse to the language of pedagogy. Dickinson resists the didactic separation of children from animals; it is in their connection with one another that the possibility for poetic expression lies. Yet even in a poem like this one, that possibility is always deferred. Being “reminded” links memory to admonition. In portraying the little boy, the “I” of first-person liberal subjectivity can be “reminded” of the “little Dog” but is already part of the didactic structures that prohibit the subject’s participation in that undifferentiated relationship between the boy and the dog.

Whereas her parodic poem identifies this problem, Dickinson reaches in other works for a “Phraseless Melody”52 by reshaping her relationship to language—that is, by making poetry itself animate. Animals mark in Dickinson’s work the liveness of a natural language beyond social silencing:

Many a phrase has the English language—

I have heard but one—

Low as the laughter of the Cricket,

Loud, as the Thunder’s Tongue—

Murmuring, like old Caspian Choirs,

When the Tide’s a’lull—

Saying itself in new inflection—

Like a Whippowil—

Breaking in bright Orthography

On my simple sleep—

Thundering it’s Prospective—

Till I stir, and weep—

Not for the Sorrow, done me—

But the push of Joy—

Say it again, Saxon!

Whereas Bullard maintained a differentiation between human beings and animals by using simile to establish a third entity, language, as the basis of comparison and distinction, Dickinson here makes language itself the locus for relating animal and human subjectivity. The “one” phrase withheld is figured in relation to “the laughter of the Cricket” and the “new inflection” of the “Whippowil.” This utterance takes on the shape of “Orthography” in Dickinson’s “simple sleep.” Akira Lippit’s work is useful for reading this poem: through an interpretation of Freud’s dreamwork, Lippit locates “a kind of originary topography shared by human beings and animals” in which “the animal becomes intertwined with the trope, serving as its vehicle and substance.”54 Lippit coins the term animetaphor to describe the animal as both “an exemplary metaphor” and an “originary metaphor” and argues that animals function “as the unconscious of language, of logos.” Following Jacques Derrida, he argues that logos “is engendered by a zoon, and can never entirely efface the traces of its origin. The genealogy of language … returns to a place outside of logos. The animal brings to language something that is not a part of language and remains within language as a foreign presence.” The animal thus takes on the role of “a vital metaphor, that enters the world from a place outside of language,” a “figure that is metamorphic rather than metaphoric.”55 Key to Dickinson’s imagining of this metamorphic figure is her odd enjambment: “Like a Whippowil—/ Breaking in bright Orthography” brings the “new inflection” of the phrase in conjunction with “the branch of knowledge which deals with letters and their combination to represent sounds and words.”56 Dickinson is literalizing one of Higginson’s odder suggestions, that “kittens … about the house supply the smaller punctuation in the book of life; their little frisks and leaps and pats are the commas and semicolons and dashes, while the big dog puts in the colons and the periods.”57 Dickinson locates animal presence in orthography, in writing itself.

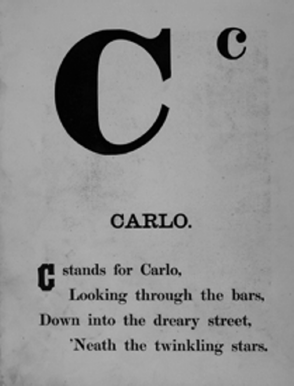

To achieve a vital poetry beyond the parameters of animal metaphors, Emily Dickinson deconstructs liberal subjectivity by alphabetizing her poetry. “Carlo” participated in the nineteenth-century vogue of animal alphabets that linked a letter with an image and with rhymed text to initiate children into literacy. In The Picture Alphabet (1879) by “Cousin Daisy,” the picture of a scruffy dog looking through bars (figure 4.1) is accompanied by the rhyme: “C stands for Carlo, / Looking through the bars, / Down into the dreary street, / ’Neath the twinkling stars” (figure 4.2).58 This kind of animal alphabet participated in the structures of liberal subjectivity. As Patricia Crain has documented, “By the beginning of the nineteenth century, alphabetization supplants rhetorical training, not only as a mode of communication but as a primary structuring of subjectivity.” Alphabets function as an “androgyne, moving back and forth between text and image,” and complicate the relationship between textual and physical representation. The extensive use of animals in these alphabets also indicates “that there are two kinds of utterances: a natural, irresistible, autonomic kind, which we share with the animals—an exhale, a cry of a baby, the communication between working man and working beast; and an artificial, learned kind—that of alphabetic, educated speech, which we draw from the animals, but which distinguishes us from them.”59 Dickinson aims to recapture the former utterance, that noise, in her use of animal orthography.

The animation of orthography reshapes the relationship between writing and subject formation. “Carlo” is an anomaly in Dickinson’s references to animals in that he is one of only three named animals (Carlo, Chanticleer, Pussy). Even those animals are not named individually but generically; they participate in the larger animal orthography of Dickinson’s poetic enterprise. In fact, the sheer range and number of animals Dickinson mentions in her poems is astonishing: by my count, she lists more than seventy different animals and names at least one animal in 20 percent of her poems. In creating an animal orthography, Dickinson then strains beyond metaphor to an animetaphor that gives poetry itself an extrasocial liveness, as one of her most famous poems illustrates:

I heard a Fly buzz—when I died—

The Stillness in the Room

Was like the Stillness in the Air—

Between the Heaves of Storm—

The Eyes around—had wrung them dry—

And Breaths were gathering firm

For that last Onset—when the King

Be witnessed—in the Room—

I willed my Keepsakes—Signed away

What portion of me be

Assignable—and then it was

There interposed a Fly—

With Blue—uncertain—stumbling Buzz—

Between the light—and me—

And then the Windows failed—and then

I could not see to see—60

Having “signed away” that “portion of me” that is “Assignable,” Dickinson relinquishes the scene of domestic confinement in the “room” and the social “witnessing” to harness the “Breaths” for her own postliberal subjectivity. The subject’s death enables an animation of the poem itself: incessant buzzing and alliterative sounds invoke the impersonal fly whose intervention in the first line separates the “I” of liberal subjectivity from an undefined “I” that gains animation from the scene of death. Animals allow Dickinson to play one kind of death against another. The death of liberal subjectivity is the scene of an imagined overturning of the animal’s figurative death and an entry into a poetic liveness.

Dickinson’s letter to Higginson stages just such an animal orthography:

Carlo died—

E. Dickinson

Would you instruct me now?

Starting with C for “Carlo,” moving to D for “died” and E for a signature, she replicates in her lines the progression of the alphabet. Adding another D for “Dickinson,” she also symbolizes the rhyme scheme of the poems associated, as Bullard’s verses illustrated, with children’s education into a relationship with animals: CDED. Her concluding question to Higginson, whom she admired as a naturalist,61 ironizes the didactic lessons that animals impart: she has, indeed, been well instructed. The fact that “Carlo died,” then, poses a threat and opens up a possibility for Dickinson’s enterprise. As Higginson put it, “A dog is itself a liberal education, with its example of fidelity, unwearied activity, cheerful sympathy, and love stronger than death.”62 In staging her carefully learned lessons of animal pedagogy, Dickinson portrays Carlo as a figure for liberal education. But she also takes his literal death to explore Higginson’s promise in that the dog exceeds the parameters of liberal subject formation and provides a figure of liveness beyond social formation. The danger here is that this development naturalizes social formations; in turning to representation, Dickinson offsets the reemergence of ontology with an emphasis on orthography. Carlo’s literal death opens the possibility for his orthographic liveness; through Carlo, “E. Dickinson’s” subjectivity can again become an open-ended question.

I have been tracing an arc that links the ontological questions posed by current affect theory to Lockean origins and subsequent intellectual receptions of liberal subject formation. Post-structuralist affect theory and liberalism open a space for radical alterity. But they too easily foreclose that space by reinscribing affect in an ontologically defined frame that distinguishes between the human and its animal others. At stake in that foreclosure is the production of a particular notion of subjectivity as marked by an individuality independent of others and clearly demarcated by the separation of reasoning from embodiment. Looking at animals gives us a different account of the subject—as relational and contingent on an alterity that cannot easily be reinscribed in the registers of either abstract rationality or embodied affectivity. Because that alterity is both physical and representational, it enables us to recognize that reading is a bodily act and that the body is a readerly act. These two modes of meaning making are contingent on but not reducible to each other; they function as one another’s excess and différance. In the process, they unhinge the naturalizing discourse of ontology and point to ontology itself as a construct that emerges relationally. Through the literal and figurative presence of animals, we come to see a fundamental relationality that points to the contingencies of our being. It is in that relationality that new possibilities for subjectivity and poetry emerge.