CHAPTER 3 1956, THE BEGINNINGS OF RACIST ATTACKS ON TENNESSEE SCHOOLS

Nashville Public Library, Special Collections, Nashville Banner Photos

Guide to the Racists in this Chapter

Emmett Carr Middle Tennessee Klan Leader and Pro-Southerners Leader

Asa Carter Renegade Klansman from Birmingham

Donald Davidson Local Racist Poet

Dr. Edward Fields Stoner’s Partner in Crime

John Kasper Segregationist from New Jersey

Jack Kershaw Davidson’s Lackey

Ezra Pound Non-Local Racist Poet

J.B. Stoner Chattanooga and Atlanta Klansman

The First Schools in the State to Desegregate

In 1954, Nashville had the first schools in the state to desegregate—Father Ryan High School (a boy’s school) and Cathedral Elementary and High School (the elementary school was mixed gender, the high school was for girls).

The desegregation of these two Catholic schools is really fascinating. The Catholic Church had already been pressuring Catholic dioceses in the American South to desegregate.26 With the Brown v. Board of Education decision, the Nashville diocese saw the writing on the wall and decided to act of their own volition and on their own terms instead of waiting for either the larger Church or the federal government to force the issue.

The Nashville diocese informed parents that the Black Catholic schools were in need of major maintenance and renovations; when they were inspected, they would likely not pass (though the Black schools stayed open, so whether this was true or, maybe, would be true in the near future, is unclear). These Black students could either be moved into more well-repaired schools with white students or Catholic families were going to have to pony up the money to fix the Black Catholic schools. The diocese framed integration as the less expensive of two options. It also told Catholic parents that they were no longer required to send their kids to Catholic schools, so if they were really opposed to their children going to school with children of other races, they could put them in public school.

As good a case as the diocese presented for integration, this still must have been outrageous to some parents. Yet, though the diocese must have been having these discussions at least throughout the summer of 1954 to give parents time to withdraw their kids and get them registered in public school, if need be, no one breathed a word of this to the media. The first day of integrated enrollment in Tennessee came and went without broad notice. It wasn’t until two weeks later that the Tennessean became aware of it. On September 5, on an inside page, the Tennessean ran a short story, “Catholics Enroll Negro Students: Father Ryan, Cathedral Admit Unannounced Total.”

The story read, in part:

This is the first year in which Negroes have been admitted to Catholic schools on a non-segregated basis. Bishop William L. Adrian announced the change in school policy following the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling that segregation was illegal.

Father Frank Shea, assistant superintendent at Father Ryan high school said yesterday 293 students had registered.

“We don’t keep track of the number of Negro students we have,” he said, “so I can’t give you any figures.”27

There’s a story, I don’t know how true it is, but I like it so I’m going to tell you, that Shea’s actual quote was something more like, “We don’t have white students and Negro students. We have Catholic students. We don’t keep track of the number of Negro students we have, so I can’t give you any figures.”

No media were present for the first integrated day of school in Nashville. But this quiet, massive change did not go unnoticed by racist terrorists.

The Plot Against Father Ryan

By January 1956, the headquarters of the Pro-Southerners had moved to Memphis and Nashville’s own Emmett Carr, age 45, had formed a Nashville branch. Carr was best known for his leadership of the Middle Tennessee Klan, but interestingly, the local papers all noted that Carr was ex-Klan at this point and that he intended the Pro-Southerners to be nothing like the Klan, being more devoted to protecting segregation through voting and legislation than violence. In this way, they were similar to Donald Davidson’s group. But like the Tennessee Federation for Constitutional Government, what the Pro-Southerners’ public position was and what they were actually plotting were two different things.

Here was Carr’s plot:

On February 7, 1956, Memphis Confidential Informant T-5, who has furnished reliable information in the past, advised that EMMETT CARR and the Pro-Southerners were organizing white high school students in the underprivileged sections in Nashville, Tennessee. Informant stated that this organization was being done in order to get the students to go to Father Ryan High School, an integrated Catholic boys’ school in Nashville, some Saturday night during a basketball game and start a riot. Informant stated the organization had picked Father Ryan High School because of the fact that this is a Catholic high school and because of the fact Negroes have been admitted to it as students.28

The FBI file also reveals that this informant got his information from a Catholic guy “who had been in personal contact with EMMETT CARR.”

This tells us a few things—that the desegregation of Father Ryan and Cathedral did send at least some racist Catholics to organized anti-Catholic racists who accepted them; that white teenagers could be enlisted in racial violence; and that integrated sports was especially alarming to racists.

But the fact that this riot never happened also tells us something. I asked Frederick Strobel, a Catholic historian in Nashville, about Catholic school desegregation and whether the Church knew about this plot. He didn’t think they had known, but he pointed out that one reason the riot may not have come off is that there were hardly ever, if ever, any Black students at basketball games in the early days of desegregation. They weren’t yet allowed on the Father Ryan team and Black students didn’t, as far as he knew, attend many evening activities at the school. So, it’s very likely that even if the rioters had shown up, they would have found a gym full of white people. That would have sucked the wind right out of the rioters’ sails.

The lesson here? Racial violence needed to be directly linked to the presence of Black people in formerly white spaces or you couldn’t count on your foot soldiers to go through with it.

By March 1956, the Pro-Southerners were falling apart, and Emmett Carr was back with the Klan. By September, he was totally done with the Pro-Southerners.

One interesting thing the FBI file notes is that in May 1956, Carr may have taken several carloads of Nashville Pro-Southerners to a Klan rally in Chattanooga.

John Kasper, Ezra Pound’s Biggest Fan

John Kasper has long been most people’s main suspect in the Nashville bombings, since the bombings started after he arrived in Nashville in 1957 and they concluded after he got tired of going to prison for being a racist activist in the early ’60s. The problem with Kasper as a suspect is that while he could rile a crowd, he wasn’t very good at actually committing terrorist acts. The plots we know he headed up fizzled out.

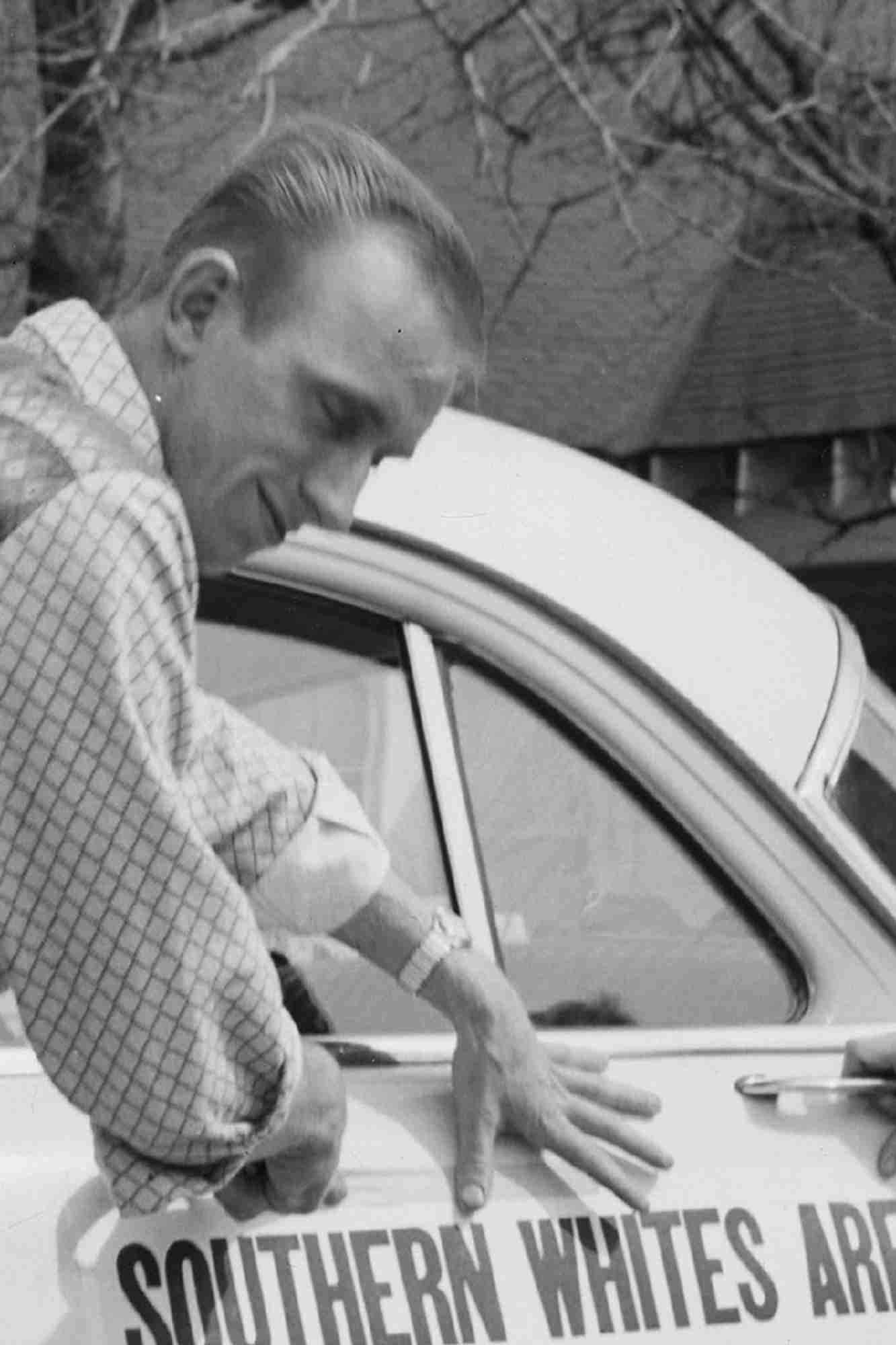

AP Photo

Also, a lot of other racists loathed him. If our bombings could have feasibly been pinned on him, it’s very likely that some other racist, possibly even Emmett Carr, would have told the world that Kasper did it. Still, it’s also obvious that Kasper was an important part of the mix that led to Nashville’s bombings; Kasper wasn’t the mastermind behind our bombings, but it’s unlikely our bombings would have happened without him.

Kasper was born in 1929 in Camden, New Jersey. His parents were very conservative Protestants, and by the time Kasper came to Nashville, his mother was attending a Bible Presbyterian Church in New Jersey, the same small sect Nashville’s Rev. Fred Stroud belonged to.29 As Kasper put it in a letter to his mentor, poet Ezra Pound, “Now der Gasp wuz borned at Camden, New Jersey and brung up in Pennsauken, N.J. Ma is a renegade Catholic, Pa was a Lutheran, and we wuz members of the 1st Presbyterian Church of Merchantville.”30 Call it a fake patois, call it baby talk, whatever this way of writing was, it certainly illustrates the strange relationship that developed over the years between Pound and Kasper.

Kasper attended Columbia University, which was where he became a fan of Pound’s and began corresponding with him. At Pound’s request, Kasper started a small publishing company in 1951—Square Dollar Press—which published Pound. During his time in New York City, Kasper also ran a bookshop in Greenwich Village. At this point, Kasper was already a raging anti-Semite, but he was also holding integrated dance parties at the shop, dating a Black woman, and, according to the FBI, sometimes sleeping with a Black man.

Kasper’s anti-Black attitudes seemed to more fully form once he moved to Washington, D.C., to be closer to Ezra Pound, who was imprisoned at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in the city on charges of treason for his fascist activities during World War II. Pound and Kasper corresponded extensively. Luckily for Pound defenders, Kasper destroyed the letters he received from the poet, so we don’t know what kinds of direction and encouragement Pound was giving Kasper. The letters Pound kept from Kasper, though, make it clear that Kasper was keeping Pound up to date on his activities and that Kasper felt his activities would please Pound.

I think—and this is peak nerdy—that Pound has benefited from so few scholars looking at him and Donald Davidson together. As long as Pound defenders can say, “Come on! How could a brilliant poet be a dangerous and virulent racist providing support and inspiration to racial terrorists? Point to one other example!” there’s always doubt.

But what we in Nashville know, or should now know, is that there was one other very prominent example: Donald Davidson. And if a deeply beloved, well-regarded professor at the city’s elite university could do this, why couldn’t a guy hiding from treason charges in a hospital room do the same?

Oddly enough, considering all they had in common, Davidson and Kasper didn’t work together much. Pound scholar and Kasper biographer Alec Marsh writes, “Davidson was an ideologue whose vocation as a poet, agrarian philosopher, Jeffersonian principles, and Southern orientation overlapped Pounds in several ways, and might have been a natural ally, even a moderating influence on Kasper.”31 Kasper may have been a dynamic, charismatic, persuasive white supremacist who was out in the streets calling for violence, but he was a carpetbagger, and it’s not surprising that Davidson—and Carr—wanted little part of him.

In direct response to Brown v. Board of Education, Kasper founded the Seaboard White Citizens Council in the Washington, D.C., area. This put him fully on the FBI’s radar, and they were tracking him as his little band of racists burned crosses and picketed the White House. Kasper was also a leader in the Tennessee White Citizens Council, though, since Nashville already had Davidson and company, Tennessee wasn’t desperate for another group of ostensibly “decent” racists, especially because Kasper was so openly aligned with the Klan—at least at first.

The Clinton, Tennessee, Riots

Kasper came to national prominence as a segregationist leader in the fall of 1956, when Clinton High School, in Clinton, Tennessee, just north of Knoxville, desegregated. (This probably goes without saying, but I’ll say it anyway, Looby was one of the lawyers on the case that led to Clinton desegregating.) Kasper came to town shortly before the start of school and called for pro-segregationists to meet up and picket. The first day of school, Monday, August 26, was okay. Not great, but there were no major incidents.

But the next day white people were pissed, and John Kasper ran around giving fiery speeches that only stoked their anger. On Wednesday, the federal judge who had ordered Clinton desegregated issued a temporary restraining order against Kasper and his followers. Kasper turned around and held a rally of 1,000 to 1,500 people, where he called the restraining order meaningless. The judge had him arrested on contempt charges.

This did nothing to calm the racists. Asa Carter, a 31-year-old Klansman from Birmingham, Alabama, came up to join the protest efforts.32 Carter’s presence in Clinton should have been alarming. He had recently been fired from his job as a syndicated radio host for his inflammatory rhetoric and had to part ways with the Alabama Citizens Council as a result. Yes, that’s right, he was too racist for the “respectable” racists of Alabama. Let that sink in. And he was welcome in Clinton. Over Labor Day weekend, the racists rioted. They overturned cars, smashed windows, and threw dynamite in Black neighborhoods. They threatened to dynamite the mayor’s house, the newspaper plant, and the courthouse. Governor Frank G. Clement sent in the National Guard to keep order.

In the wake of this, some racist whites were arrested. Donald Davidson sent Jack Kershaw over from Nashville to bail out those he could, except John Kasper.33

This didn’t end racist violence. Throughout the fall, white Clinton residents burned crosses on the lawns of high-school teachers and civic leaders who supported integration. Someone fired shots at the home of two of the Black students.

Kasper, who was out on appeal for his contempt charge, came back to Clinton in November to organize a Junior White Citizens Council in the high school. If you see pictures of the Clinton Junior White Citizens Council, you won’t fail to notice that, in addition to forming a group willing to serve his racist ends in the halls of a school he couldn’t legally enter, Kasper had found a way to surround himself with cute girls who adored him.

But an interesting thing started happening in Clinton, a crack that would only widen once Kasper got to Nashville. Word of Kasper’s life in New York City got out. People learned he had dated a Black woman and thrown those cool dance parties. Some racists were like “Dude, what?” and in the wake of that question, a conspiracy theory began to develop. Kasper, the theory went, was not actually a white supremacist, but was an agent provocateur sent by the FBI or the Jews or both to make Southern white supremacists look like unhinged, violent lunatics who other white people should not support, but be afraid of.

But, in fact, Kasper’s behavior is easily understood by his own stupid conspiracy theory that Black people, when left alone, didn’t want integration in the South, but were, instead, being led astray by the wily Jews who convinced them to be unhappy in their lot. If Kasper wholeheartedly believed this while he lived in NYC—and all evidence is that he did—then why couldn’t he befriend and even be romantically involved with Black people, who, if kept free from Jewish influence, were fine people who just weren’t as good as him? Then, when he came south and found an insufficient number of Jews in East Tennessee to sustain such a level of trickery, he could have come to believe that Black people weren’t just the unwitting pawns of Jewish people, but were, instead, working hand-in-hand with them. He then became more straightforwardly anti-Black, while still being a raging anti-Semite.

But Clinton racists began to suspect Kasper’s motives. So, they (yes, the racists) bombed Kasper’s Clinton headquarters to try to get rid of him.

Kasper came to Nashville not just because we had a fight over desegregation brewing here, but also because he had worn out his welcome in Clinton—not with the integrationists, but with his fellow segregationists.

J.B. Stoner, Chattanooga Klavern No. 317, and the Rise of the Dixie Knights

Before we can turn our attention fully to Nashville, we need to spend a little time looking at some of the segregationists from Chattanooga. I wish we were spending more than a little time, but I haven’t been able to find out much about this era in Chattanooga’s racist history.

J.B. Stoner was born in 1924 and grew up in Chattanooga and its suburbs. By the time he was sixteen, he was corresponding with Nazi propagandist Fred “Lord Haw Haw” Kaltenbach. In 1940, the Chattanooga Times reported that Lord Haw Haw had called out a sixteen-year-old Stoner specifically by name on his radio show: “Young Mr. Stoner, you are a brave lad. I will try to see to it that you get the services of a German surgeon when the war is over.”34 35 Stoner had been stricken with polio when he was a toddler and one of his legs was considerably shorter than the other. Stoner assured the Times, “I am not in sympathy with the German cause. I am against Jews, and Hitlerism.” During the 1940s, Stoner started the “Stoner Anti-Jewish Party,” a political party that was … well, you can read. It’s through this organization and their shared loathing of Jews that he and Ed Fields, out of Louisville, would become lifelong friends. It seems likely that his antisemitism accounts for his liking of John Kasper.

When he was eighteen, in 1942, Stoner re-chartered a chapter of the Klan. This Klan chapter, we know from Stoner’s FBI file, was part of the Associated Klans of America, which had chapters in Atlanta and Knoxville, among other places, and we know that Stoner travelled to Knoxville and Atlanta to meet with those chapters.

Stoner told the FBI that after a fight with Klan leader Dr. Samuel Greene (apparently over Stoner’s anti-Jewish activism) Stoner resigned from the Klan. But by 1949, Stoner’s name was on the membership list of Klavern no. 317. I haven’t been able to suss out if Klavern no. 317 was the chapter that Stoner chartered in 1942, but it is clear that the goals of Klavern no. 317 and Stoner’s personal goals were closely aligned. Klavern no. 317 was kicked out of the Klan—yes, the whole Klavern—in, it seems, 1950, for their anti-Jewish activity. Once Stoner moved to Atlanta, Klavern no. 317 was able to rejoin the Klan. In Atlanta, Stoner met in person the handsome racist, Ed Fields (born in 1932), who had been a member of the Nazi organization known as the Black Front, in addition to other groups like the Columbians, and the Christian Anti-Jewish Party. Fields was one of the founders of the National States Rights Party. They became close friends.

There are a few reasons I think it’s important for us to keep an eye on Klavern no. 317 in relation to our bombings, even though there is so little information about them available:

One—these are the Tennessee assholes Stoner knew best and with whom he had long-term friendships. When Stoner told people that he had a “man in Chattanooga” who would do bombings for him, the most likely place to look for that man would be Klavern no. 317.

Two—when the Birmingham, Alabama, authorities were trying to figure out how all the dynamite was coming into their city, since much of it was a brand not sold in Alabama, they reached out to cities across the South for information. Memphis told Birmingham that the dynamite was coming out of East Tennessee, being stolen out of the mines and moved through some network throughout the South.36 The most obvious network of people was the Klan, and Klavern no. 317 sat right at the nexus of the most violent parts of that network.