CHAPTER 5 THE HATTIE COTTON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL BOMBING

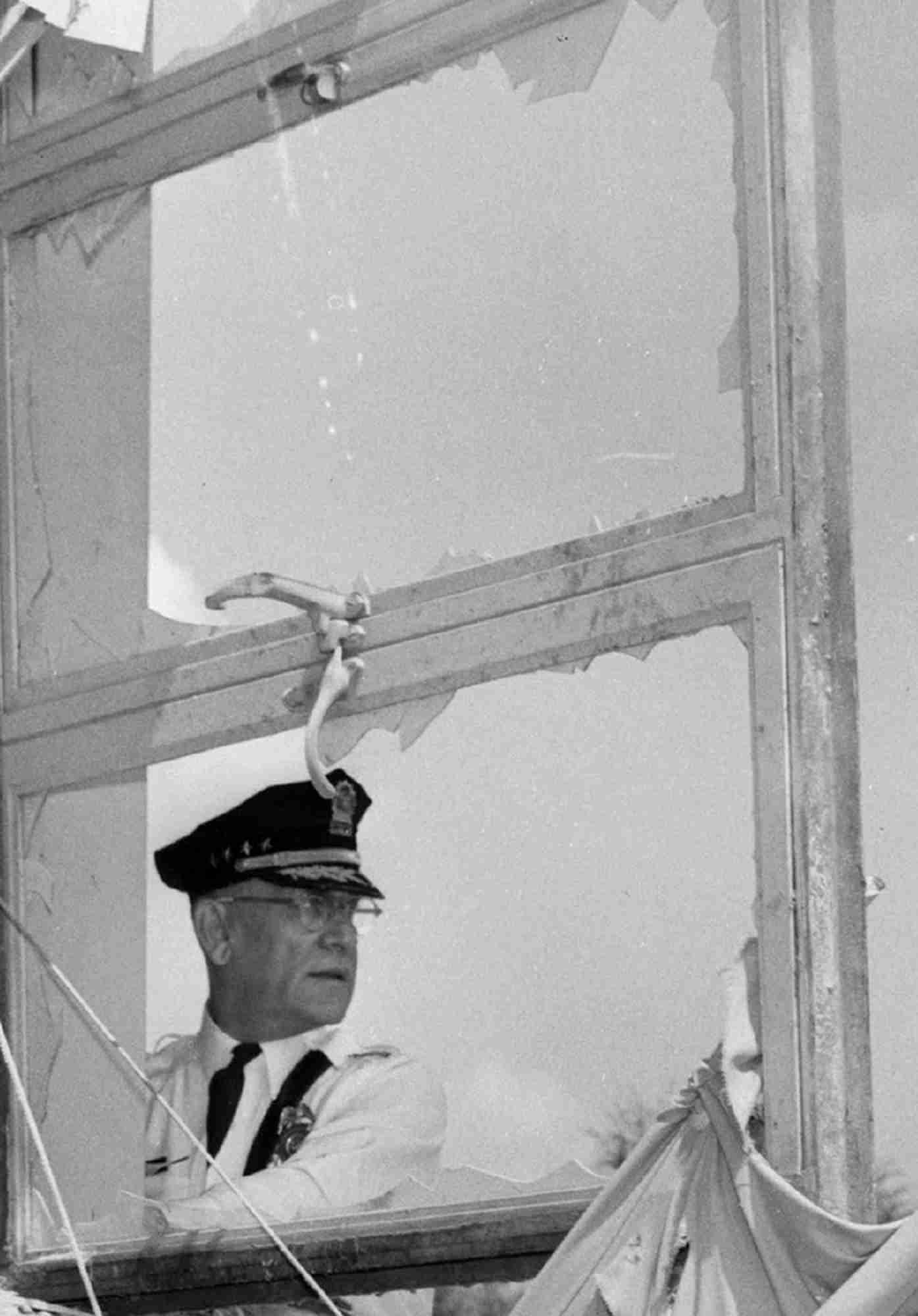

Nashville Public Library, Special Collections, Nashville Banner Photos

Guide to the Racists in this Chapter

Jack Brown Leader of Chattanooga Klavern 317

Emmett Carr Middle Tennessee Klan leader

John Dalton Member of Chattanooga Klavern 317

Bill Hendrix Florida Klan leader

Eldon Edwards Imperial Wizard of the US Klans

John Kasper Rabblerouser

Jack Kershaw Donald Davidson’s errand boy

Thomas Norvell FBI informant

Charles Reed Kasper supporter and friend of Thomas Norvell

September Begins

John Kasper was over in North Carolina until late Thursday of the first week of September 1957. The Tennessean covered his return. This is the whole article:

Kasper Returns, To Try Boycott

Segregationist John Kasper returned to Nashville from North Carolina last night and addressed a gathering of segregationists in front of the War Memorial building.

Kasper told the group that an effort will be made to organize a boycott of integrated schools here by white students. He said the organization would be attempted by the local White Citizens council and the Ku Klux Klan. Kasper spent last week in North Carolina speaking against integration there.

Others addressing last night’s meeting were the Rev. Fred Stroud and KKK leaders Emmett Carr and E.S. Dollar.57

There’s a lot going on here that’s worth noting. One, we see Kasper at the War Memorial building, which means he is, in essence, at the state capitol, which is right across the street. He’s not at the site of Nashville’s city government, which is only three blocks away. He’s taking his mob right to the state. He’ll be back in this location.

This “involving the students” thing is something we know Kasper did in the past—see, for instance, his cadre of cute girls over in Clinton. But as we know from Emmett Carr’s Father Ryan plot, it’s also a strategy Carr and the Klan had been wanting to use. A big problem with this strategy is that Nashville was just integrating its first grade. Who were these segregationist boycotters in the first grade going to be?

But the most crucial thing this story tells us is that whatever Carr’s problems with Kasper were, by early September, he had set them aside and Kasper and Carr were now openly plotting to thwart integration. Kasper had the local Klan on his side.

The Hattie Cotton bombing took place just after midnight on Tuesday, September 10, 1957, the culmination of activities that took place all over town the preceding weekend and on the first day of school: Monday, September 9.

I’m going to relate the incidents of this weekend in chronological order, as best as I have been able to piece them together from newspaper stories and the FBI files I have available to me. If you feel like the things I’ve told you to this point might be particulars you hadn’t heard of, but that none of it really conflicts with what you already knew about these bombings, here’s where things are going to start to get weird for you. Honestly, things are about to get weird in general, but readers who don’t know about the bombings already (especially non-Nashvillians) won’t experience the dissonance of finding out that what they thought they knew was pretty wrong.

The FBI at this time was not interested in getting dragged into what they saw as local squabbles. They wanted to know what was going on, but that was the extent of it. Their goal was to preserve their access to information. So, if at any point in this next part, you’re wondering, “Why didn’t the FBI tell the police or arrest so-and-so themselves or do this or do that?” just consider whether doing so might have weakened their ability to collect information.

Also, consider that the police just wanted to keep order and restore calm. They wanted to arrest and run off the rabble rousers, and they wanted the mobs to be afraid to cause more chaos. This isn’t exactly the same as finding and prosecuting the bombers, which would also be at odds with the FBI’s goal of keeping information flowing.

Plus, remember that “good,” “respectable” white people were segregationist activists. We don’t know all the ways prominent white Nashvillians might have been tied into efforts to use violence to stop integration—not just the bombings, but the mobs that preceded them. I think it’s fair to assume, based on what we know did happen, that the police were not eager to push too hard down paths that might jack things up for people they knew or people who were well connected.

Okay, all that being said, here we go.

Thursday, September 5

On Thursday, September 5, Kasper came back to Nashville and gave his speech calling for the school boycott. Klan leadership was present and approving. Meanwhile, FBI Special Agent Norwood talked in person with Thomas Norvell, who had contacted the FBI after being alarmed by the rhetoric of the crowd at other Kasper rallies. Norvell told Norwood that “he has never heard KASPER make any statement indicating that he adheres to violence in connection with the racial situation58 and that to the contrary, KASPER has always made statements to the effect that he is opposed to violence. He stated that some of the people who have been at the KASPER meetings have talked of possible violence.”59

Friday, September 6

On Friday, September 6, a last-ditch effort by segregationists to forestall integration failed in court and Judge William Miller ordered Nashville to begin desegregating first grade on Monday. Present in the courtroom was Z. Alexander Looby, who was the lawyer for the parents who brought suit to desegregate. So too was John Kasper, unsurprisingly, and Donald Davidson’s sidekick, Jack Kershaw. Nellie Kenyon in the Tennessean reported:

“Since Judge Miller admitted from the bench that he had already made up his mind before coming into court and didn’t even read our brief (submitted by the Parents’ Preference committee),”said Jack Kershaw, vice president of the Tennessee Federation for Constitutional Government, “if there is any way humanly possible to appeal the decision it should be done right away. We feel an appeal should be made immediately, because if it is not, we fear violence.”60

Saturday, September 7

That Saturday, September 7 (according to what the FBI was hearing from Norvell), John Kasper had gone to the home of Charles Reed, a Klansman who had been collecting Kasper’s mail for him. Kasper, according to Reed as recounted by Norvell, had “some sticks of dynamite and four quarter fruit jars of powder in his possession.61 By innuendo, Kasper allegedly indicated to Reed that the dynamite and powder would be used on a school.”62 Kasper, according to Norvell, told Reed that the dynamite “came into Nashville from outside the city and had not been purchased locally.”63 Reed, though, was being less than cooperative. He denied everything Norvell told the FBI.

Sunday, September 8

On Sunday, Norvell called Agent Norwood again and “stated that he had learned from REED that KASPER had contacted REED and that the use of the dynamite would be delayed for a week or ten days.”64 Meanwhile, John Kasper and Bill Hendrix, Kasper’s Florida Klan friend, held a rally in their favorite field in West Nashville. Two hundred people attended and listened as Kasper called for a student boycott and picketing at schools on Monday. After it started to rain, the mob caravanned to Bailey School in East Nashville and held another meeting there.

The Nashville police had officers attending Kasper’s rallies, collecting information on what he was telling his followers. According to the FBI, the police chief and the DA intended that these officers would then testify in court as to what they’d heard Kasper saying, should the need arise. Since the police files are missing, we don’t know much about the scope of this plan, just that it pissed the FBI off. We’ll get to why the FBI might have been so angry.

Monday, September 9, The First Day of School

Monday, the first day of school, was a complete shit show. The schools that desegregated first grade that day were Glenn, Jones, Buena Vista, Fehr, Hattie Cotton, and Clemons—though these were not all the same schools where Black students had preregistered. The Black students who tried to go to Caldwell were turned away for technical reasons, and the little girl who was supposed to go to Bailey was transferred to a Black school by her parents at the last minute. No one knew Patricia Watson would be attending Hattie Cotton until she showed up and registered that morning. No protesters knew to be waiting for her there. No angry mobs thronged outside. John Kasper did not visit Hattie Cotton.

Angry crowds of racists did gather at most of the other schools. John Kasper and Rev. Fred Stroud spoke to those crowds at Glenn, Caldwell, Fehr, Jones, and Buena Vista. Kasper was photographed at Bailey. Kasper threatened violence and urged the gathered white people to come to his rally that evening on the steps of War Memorial Auditorium. At Glenn, a group of fifteen to twenty people harangued parents and tried to block them from bringing their children into the school. This group (of adults!) surrounded the little Black six-year-olds and jeered at them. The situation was tense enough that many parents, white and Black, came and got their kids. Some in the crowds threw rocks and bottles—the bottles being doubly terrifying because of the threat of an acid attack.

The Tennessean reported that Kasper told the Glenn crowd, “Keep your children at home. Some of you men who want something to do, go over to Bailey school. Some of you go over to Jones and Caldwell. We aren’t ever going to give up. They don’t have enough jails for all of us.”65

That evening, Kasper had his largest, angriest rally on the step of War Memorial Auditorium. John Egerton, in his article, “Walking into History: The Beginning of School Desegregation in Nashville,” recounts how it went:

With what seemed like a mixture of confidence and desperation, Kasper stood before his audience that Monday evening and slowly heated his rhetoric to the boiling point. Using language laced with dehumanizing epithets and images of violence, he pressed once again the emotional buttons of defiance and menace that had always seemed to work for him in the past: communism, atheism, mongrelization, rape, mayhem. The crowd was on his leash, waiting to be led. He told them they had a constitutional right to carry weapons, and the time had come for them to arm themselves and get into the fight.

They moved across Charlotte Avenue to the steps of the State Capitol, with Kasper in the lead. “We say no peace!” he shouted. “We say, attack, attack, attack!” Then, brandishing a rope, the Jersey racist with his newly-acquired Southern accent closed with a final flourish: “This is Dixie! Who do they think they’re playing with? We’re the greatest race on the face of the earth! Let’s for once show what a white man can do!” Standing gaunt and grim-faced, Kasper absorbed the frenzied crowd’s deafening roar of approval. He looked for all the world like the leader of a lynch mob.66

If it looked like a lynch mob, that was in part because Kasper seemed to have a victim in mind. The Tennessean reported that a policeman testified that Kasper had taken that rope, formed it into a noose, and “remarked that it would ‘fit’ the neck of City Councilman Z. Alexander Looby, a Negro.”67 Meanwhile, police were stationed at each of the schools where demonstrators had been active that day. Hattie Cotton was apparently not considered an active site.

According to the FBI, when Charles Reed came home Monday night at about 11:00, he “found Kasper waiting for him in a distraught emotional state. Kasper asked him ‘where the hell’ he had been when he needed him. Kasper indicated he wanted Reed to go with him, but Reed refused, saying he was all wet from the rain.”68 Kasper left.

The Explosion

Egerton reports that white people were rioting in pockets all over town—mostly young, angry men. “From their midst came a whispered rumor that Fehr would be blown up at midnight.”69 But police were guarding Fehr. Instead, at 12:33 A.M. on September 10, Hattie Cotton exploded.

The bomb went off at the east end of the main hallway, between the library and a classroom. Walls crumbled. Ceilings fell. Every window was knocked out.

The Tennessean described the authorities’ theory of the bombing:

The investigators believe approximately a case of dynamite, possibly still in its box, was placed outside the building in the porchway of the entrance on the east side of the school.

The detonator was probably an electric cap connected to wires, rather than a dry fuse set by fire, investigators said. They believe this because police found detonating wires near the school.

[ …]

O.O. Lee, state fire marshal whose office is investigating the explosion, said “We estimate that approximately 100 sticks of dynamite caused this explosion.”

[ …]

He said that investigators agree that whoever set off this dynamite either was very professional and was informed as to his margin of danger—or he was very lucky. From the effect of the blast it would seem that he “knew just what he was doing,” Lee said.

To successfully set off the charge and escape injury it was probably necessary to string wires some 50 feet from the place the dynamite was placed. From this point the charge could have been exploded by a battery. The explosion would have been immediate and the dynamiter would have been able to escape in a waiting car driven by a confederate.70

Within ten minutes of the blast, police were rousing John Kasper out of bed at his new East Nashville address on Scott Avenue. He had apparently been asleep. The noise hadn’t woken him, even though people as far away as Donelson reported hearing it.

From our perspective, sixty years on, we know the police were wrong about the size of the bomb. It wasn’t one hundred sticks of dynamite—which probably would have leveled the school. Hattie Cotton’s west wing was undamaged and students were back in the building a week later. The east wing was repaired and reopened by February 1958. It seems fairly clear now that there was just one bomb and that it was substantially smaller than the police initially thought it was.

But at that moment, it must have seemed to the FBI that the bomb that blew up Hattie Cotton was not the bomb they’d been told John Kasper had. The size was wrong, plus Norvell had said Kasper’s plot had been pushed back. Based on the facts available at that time, it must have seemed like John Kasper had a plot to bomb a Nashville school with the small bomb he had shown Reed, which had been pushed to the second week of school.

When Hattie Cotton exploded and everyone thought that bomb was huge, the only conclusion the FBI could have drawn was that Nashville still had a bomb in play, that another plot—Kasper’s plot—was ongoing. Also note: the FBI hadn’t yet told the Nashville police about Reed and Norvell.71 We don’t know when or if the Nashville authorities were warned that Kasper’s crowd had a bomb plot baking, but the FBI clearly had heard that segregationists were actively planning to bomb a school and had explosives.

So, as you read this next section, keep in mind that this is all happening while the FBI had information that strongly suggested there was another bomb out there and another plot possibly in motion.

FBI Weirdness and Witness Hiding

On Tuesday, September 10, the FBI interviewed Norvell and Reed together. Norvell told the agents, in front of Reed, what Reed had told him. Reed denied saying it. The FBI believed Norvell.

At 3:37 P.M., J. Edgar Hoover sent a memo to his closest confidants at the FBI: Clyde Tolson, Leland V. Boardman, Alex P. Rosen, and Lou Nichols. In it, Hoover brought them up to speed on what’d happened in Nashville and said they had an informant who said he saw Kasper with dynamite. Hoover wrote, “Our Agent was also told to advise the Chief of Police and the Sheriff of this matter,” meaning the matter of them having an informant who had seen Kasper with dynamite.72 This pretty clearly suggests that before the bombing, no Nashville law enforcement knew specifics about Kasper’s alleged bomb plot.

At 4 P.M. in Washington, D.C., J. Edgar Hoover sent another memo to Tolson, Boardman, Rosen, and Nichols. In it, he complained about the attorney general asking Nashville’s mayor to get affidavits from the police officers who were at Kasper’s meetings, since he wanted the Bureau to secure affidavits. Both the police and the FBI were trying to find a way to get Kasper’s bond from his arrest over in Clinton revoked. But they were at cross-purposes over who should be doing what.

Hoover also spent a paragraph discussing the Reed and Kasper bomb plot, such as it was, and whether they could find someone who could corroborate Norvell’s version of Reed’s statements. And then there’s this interesting bit:

The Attorney General has told me he learned from Fred Mullen that Kasper had been arrested by the Nashville police. I stated that he was probably taken into custody for questioning regarding this matter since affidavits had been requested of the police by the Mayor. I told the Attorney General that the police did not know the identities of Norvell and Reed because we did not want their identities disclosed.73

This sounds like Hoover had had a discussion with the attorney general in the twenty minutes since he composed his last memo, and that the situation in Nashville had changed. Now the police know the FBI had heard of a bomb plot by Kasper before Hattie Cotton was blown up (and that the FBI did not tell the Nashville police about it), but the FBI was keeping the identities of their informants secret.

Then, there’s a strange memo dated September 10, 1957—though someone had handwritten September 11, 1957, on it. This memo states: “This information was furnished to the Chief of Police of Nashville and the Sheriff of Davidson County, Tennessee, on September 9, 1957.”74

This unsigned memo seems to directly contradict what Hoover wrote. Hoover made it sound like no law enforcement in Nashville knew about what the FBI had heard until after the bombing. This memo makes it sound like the FBI warned Nashville authorities that a plot was afoot, but Nashville failed to act in time to stop it.

Both scenarios are troubling. Unfortunately for the FBI, all we as a city have to help us judge which scenario is more likely is the FBI’s behavior in other instances and what the FBI wrote in later reports.

The specific later report I’m talking about was a huge one Special Agent Richard Lavin wrote on April 24, 1959. Deep within it, Agent Lavin describes exactly what happened during the Hattie Cotton bombing from the FBI’s end. I’m including the whole section devoted to the school bombing, because I think it clarifies the timeline, illuminates Norvell’s relationship with the FBI, and clearly shows that the FBI with-held information from the Nashville police. Since this report was typed in standard typewriter font, the identities of the people whose names have been redacted are fairly obvious. Norvell has a bigger white box than Reed. I’m putting my educated guesses in brackets based on the earlier information in the file.

5. POSSIBLE CONNECTIONS WITH BOMBINGS

A. Hattie Cotton School Nashville, Tennessee

W.E. HOPTEN, Director, Tennessee Bureau of Criminal Identification, on September 10, 1957, advised that the Hattie Cotton School, Nashville, Tennessee, had been bombed. HOPTEN advised that it was estimated that several cases of dynamite had been used.

On August 27, 1957, [Thomas Norvell] contacted SE JOHN D. JONES telephonically. [Norvell] advised that he had been attending meetings held by JOHN KASPER and that he and [Charles Reed] had been attending KASPER’s meetings chiefly because they were curious about his views on segregation. [Norvell] stated he was not in agreement with KASPER’s ideas and he believed that KASPER’s group would resort to violence.

On September 5, 1957, [Norvell] was contacted by SA FRANCIS W. NORWOOD and he advised that he never heard KASPER make any statement indicating that he adhered to violence and on the contrary had always made statements to the effect that he is opposed to violence. He stated that some of the people who have been at the KASPER meetings have talked of possible violence.

On September 7, 1957, [Norvell] contacted SA NORWOOD and furnished the following information which he stated he had gotten from [Charles Reed. Reed was] approached on the morning of September 7, 1957, by JOHN KASPER, who asked [Reed] if he could use dynamite. KASPER explained to [Reed] that he had several sticks of dynamite, which came into Nashville from outside the city and had not been purchased locally. He also said he had four quart fruit jars full of gun powder or an explosive of some sort.

On September 8, 1957 [Norvell] again contacted SA NORWOOD and stated he had learned from [Reed] that KASPER had contacted [Reed] and that the use of dynamite would be delayed for a week or ten days. He stated that he understood that it would be used at a school REDACTED.

[Reed] was interviewed by SAs WILLIAM L. SHEETS and EDWARD T. STEELE at his residence on the afternoon of September 10, 1957. [Reed] denied that he had had any conversation with KASPER or [Norvell] or anyone else pertaining to dynamite, gun powder, or other explosives.

[Thomas Norvell and Charles Reed] interviewed together at REDACTED on September 10, 1957, by SAs NORWOOD, STEELE, and SHEETS. At this time [Norvell] in the presence of [Reed] repeated the information previously furnished. Again [Reed] denied any knowledge and stated in the presence of [Norvell] that he did not know where [Norvell] got such ideas.

On the morning of September 11, 1957, [Reed] telephonically contacted SA STEELE at the Nashville Resident Agency Office and again denied he had any information about the dynamite and stated that he felt that if JOHN KASPER were released from jail, he would come to [Reed’s] house and that possibly [Reed] could get some information. He then stated that he could sure use some money as he was not employed and was unable to pay his debts.

On September 12, 1957, [Reed] again telephoned the Nashville Resident Agency Office and advises SA NORWOOD that he had been lying and that he did have information about the dynamite. He stated that he had actually seen the dynamite in KASPER’s possession. [Reed] then voluntarily came to the Nashville Resident Agency Office and furnished a signed statement [Reed] set forth that KASPER had come to his house on September 7, 1957, with a box of dynamite. According to [Reed], KASPER asked him to keep the dynamite, but [Reed] refused. [Reed] also stated that a day or two before KASPER brought the dynamite to his house KASPER and [Reed] had ridden around in the car a little. KASPER stated he wanted to look at the schools and see which one would be the easiest. [Reed] understood him to mean the easiest school to dynamite. [Reed] stated on Monday, September 9, 1957, he arrived home at 11 P.M. KASPER was on [Reed’s] porch and as he walked up he put a flashlight in [Reed’s] face and stated, “[Reed] where in the Hell have you been?” According to [Reed] KASPER was acting like a maniac the way he talked and waved his hands. Later that night [Reed] heard a dull thud and immediately thought that KASPER had used the dynamite.

On September 12, 1957, [Norvell] furnished a written statement to SAs NORWOOD and STEELE, in which he set forth that on Monday night, September 9, 1957, he went to the residence of [Reed] at about 9:00 P.M. After he had been there a little while KASPER came in and asked for [Reed]. Told him that [Reed] was not there. According to [Norvell] KASPER was very nervous and paced up and down on the porch. He stayed at the house about an hour and a half and stated several times that he was very anxious to see [Reed]. KASPER stated, “Tonight of all nights I wish he would get here.”

On September 13, 1957, SAC JULIUS M. LOPEZ, JR., and SA JAMES B. ANDERSON presented to FRED ELLEDGE, United States Attorney, Nashville the statements made by [Thomas Norvell] and [Charles Reed]. Mr. ELLEDGE, after discussing the matter with Mr. MC CLEAN of the Department of Justice, advised that even if the allegations were true, such allegations related to a state matter and in no way constituted an offense within federal jurisdiction.

On September 13, 1957, SAC LOPEZ furnished DOUGLAS E. HOSSE, Chief, Police Department, Nashville, the information secured from [Norvell] and [Reed].75

This version of events has clearly been polished up to make the FBI look a little less bad. But it does clarify that Norvell was someone the FBI knew and trusted and that the FBI didn’t tell the Nashville police about Reed until three days after the bombing.

What Charles Reed Actually Told the FBI

It’s worth looking at the statement Charles Reed gave the FBI on September 12, because what he said in his own words was a little different than what the FBI attributed to him.

On Saturday, Sept. 7, 1957 about 3:30 PM, Kasper came to my house at 1715 Nassau Street, Nashville, Tenn. Tom Norvell was the only other person at my house when Kasper came. Kasper parked his car, a Plymouth wine colored convertible, in front of my home. I saw him take a pasteboard box out of his car. He came in my bedroom with the box and put in [sic] on the floor at the foot of my bed. The box was about 18 inches long, 12 inches wide, and 28 inches deep. He pulled out some soiled shirts and then removed a little cardboard box about 10 inches deep and put it on the floor. Kasper said, “Reed, what am I going to do with this stuff?” I said “What’s that?” and he said “Dynamite.” I told him he could not leave it at my house as it was too dangerous. He acted mad and jittery and said “We gotta put it somewhere.” He asked me to put it under the floor of my house, but I refused. Then I happened to think of an abandoned house on Delta Street and I told Kasper to come with me. That I had thought of a better place. […] We went around the [abandoned] house to the back and set the box down, opened the top and raised up some excelsior. He pulled up a quart fruit jar. He told me that was loose dynamite. Then he picked up a stick of dynamite and handed it to me. He told me to feel of it. I saw three sticks of dynamite, one that I held in my hand, and two in the box laying in the excelsior. There could have been more in the box. Kasper pulled out a piece of wire about two and one half feet long. He said that was a fuse and that it would burn one foot per minute, or two and one half minutes. This wire was black and looked to me like it was insulated. Also looked like it had a thread of white running through itmade into the insulationnot wrapped around it. The quart jar contained a yellowish orange looking substance in the form of something like grape nut flakesin other words, not fine like sand or powder, and not coarse like a corn flake. More like you would take a hand full of corn flakes and mash them in your hand. The substance did not lay close together. The stick of dynamite I held in my hand was wrapped with brown oily looking paper. It looked like it was greasy, but did not feel greasy to my hand. I never examined dynamite before, but I believe what I held in my hand was dynamite.76

Almost as soon as the FBI decided that it was going to have to tell the Nashville police about Reed, they were coming up with reasons to disregard Reed’s statement: he wanted the reward money, he had a head injury, he was a drunk. And while it’s hard to know if the changes to the description of what Reed said he saw were deliberate or just the result of drift as things were repeated second and third hand, Reed’s own statement is much more exact and descriptive than “Reed saw Kasper with some dynamite.” Reed was able to describe the components of a bomb. Most compelling to me is that he seems to be describing a jar full of flake TNT without knowing it. Anybody would recognize a stick of dynamite (or at worst confuse it with a roadside flare), but Reed seems to have seen something he didn’t recognize and was able to describe it well enough that, more than half a century later, I can give a pretty good guess as to what he saw. That says to me that he saw something—that he wasn’t just making stuff up for the reward.

There are a couple more things to add to our FBI timeline.

Klavern No. 317 Appears in Nashville

On September 11, A.E. Shockley, principal of the all-Black Head School, received a call at the school “from an individual who identified himself as ‘Dalton, (phonetic) with the Ku Klux Klan.’”77 This Dalton said he was going to blow up Head School at 10:30 that night. This did not happen, fortunately.

The FBI checked its files to see if they might have known who this Dalton was. “The one possibility developed was a John Dalton of Rossville, Ga.,78 who according to various file references was active in the Chattanooga, Tennessee, Klavern 317 from 1950 to 1956, present status not known.”79 At the time of the Hattie Cotton bombing, Klavern 317 was headed up by Jack Brown. According to the FBI, “STONER was formerly a member of the Chattanooga Klavern No. 317 and was banished from the Klavern in 1944. He stated he rejoined Klavern No. 317 in December 1949, and was expelled in January 1950, for making a motion at a Klan meeting to throw all Jews out of Chattanooga.”80

Unbeknownst to authorities in Nashville, the same month that Hattie Cotton blew up, Imperial Wizard of the US Klans, Eldon Edwards, kicked Klavern No. 317 out of the Klan (yes, again) for—wait for it—its “alleged uncontrollable proclivity for violence.”81

But what, exactly, had Klavern No. 317 done that was so violent? The last big thing they’d done in Chattanooga was to blow up the porch of civil rights attorney R.H. Craig, in early August 1957. Nothing happened in Chattanooga in September that would warrant Edwards’s action.

But there had been violence against white people in Nashville. White children, even, since they were the vast majority of students at Hattie Cotton. And that violence sure seems like it had Chattanooga ties—Dalton and Stoner.

Remember the part where Norvell told Agent Norwood that Kasper had told Reed that the dynamite had been purchased outside the city and brought in? This is a thing J.B. Stoner was going to go on to do repeatedly in the late 1950s and 1960s. He’s alleged to have done it for the Atlanta synagogue bombing in 1958. He’s alleged to have done it for the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham in 1963.

And lo and behold, the FBI learned in 1958 that J.B. Stoner was bragging around Birmingham about having bought the dynamite that blew up Hattie Cotton. From whom? It seems pretty likely from Klavern No. 317, members of which may have even come to town to help with the job.

FBI files not only eventually give us a pretty good idea of what happened in the Hattie Cotton bombing, they also make utterly clear that the FBI at the time of the bombing—even knowing that the school had been blown up and that Kasper and his followers likely had more explosives—were not being completely forthcoming with the Nashville police about what they knew, when they knew it, and who they knew it from.

This seems outrageous. What if there was a second bomb out there? Remember, Head School had received a bomb threat. The police needed to speak with Reed immediately to try to discern Kasper’s plans for the dynamite he had (if that story was true). If they thought this bomb was the only bomb, Reed saw it in Kasper’s hands. If the goal was to get Kasper put in jail and kept there, an eyewitness is pretty damn important.

What the heck was the FBI doing?

Well, let’s see what happened to the people the Nashville police did get their hands on.