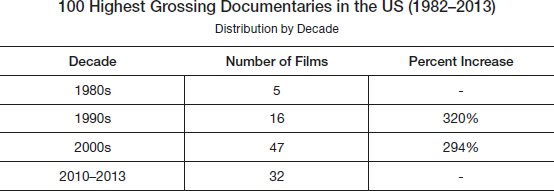

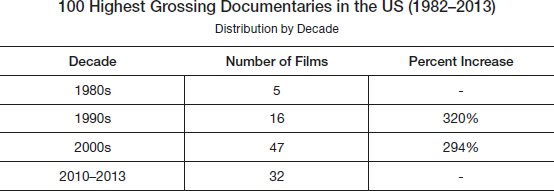

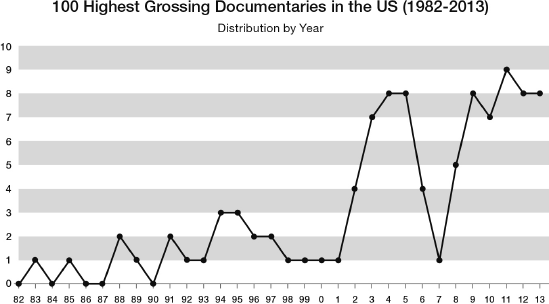

One of the most surprising and unexpected film tendencies at the beginning of the twenty-first century was the return of documentaries to movie theatres after a couple of decades dominated by hyperbolic fiction. A quick look at the list of the hundred highest-grossing documentaries in the US between 1982 and 2013 reveals that more than half belong to the twenty-first century, including the first blockbuster documentary in history,

Fahrenheit 9/11 (Michael Moore, 2004), whose box-office profits surpassed the symbolic barrier of $100 million.

1 The other titles on the list grossed between one and ten million dollars, which is not too much for a fiction film, but it is certainly much more than a filmmaker expects to earn with a project of this kind. In fact, before the 1990s, documentaries hardly made much money in movie theatres, basically because their distribution seemed restricted to television. Let us take the five most-watched documentaries in the 1980s. They were: an oddity in movie listings,

Koyaanisqatsi: Life Out of Balance (Godfrey Reggio, 1982); two biographies of celebrities,

Vincent: The Life and Death of Vincent van Gogh (Paul Cox, 1987) and

Imagine: John Lennon (Andrew Solt, 1988); and two documentaries that became film events due to their unusual profits,

That’s Dancing (Jack Haley Jr., 1985) and

Roger & Me (Michael Moore, 1989). Since then, there have been other milestones in the recent economic history of documentary film in the US –

Paris is Burning (Jennie Livingston, 1990),

Madonna: Truth or Dare (Alek Keshishian, 1991),

Hoop Dreams (Steve James, Frederick Marx & Peter Gilbert, 1994),

Bowling for Columbine (Michael Moore, 2002),

La marche de l’empereur (

March of the Penguins, Luc Jacquet, 2005), etc. – but these box office successes are just the tip of the iceberg, a brief sample of the global increase of non-fiction in the big screen.

The return of documentary film to movie theatres is, according to Michael Chanan, a reaction to ‘the inadequacies of mainstream cinema’, ‘the inanities of television’ and the lowering of production costs after the emergence of digital video (2007: 7). This first explanation has been extended by Lipovetsky and Serroy, who have related the rise of documentary to the disappearance of ‘major collective references’ and ‘the main visions of historical future’ (2009: 147; my translation). In this context, according to them, non-fiction film would serve to demystify the power discourse and to satisfy our need to feel free in – and be critical of – a system that forces us to consume everything (2009: 150). For this reason, documentary arguably fulfils a social function within the contemporary mediascape, as Chanan has highlighted: it ‘speaks to the viewer as citizen, as a member of the social collective, [and] as putative participant in the public sphere’ (2007: 16). It seems, therefore, that documentary film is here to stay as long as there are movie theatres, although these could disappear overnight without anyone noticing it, like silent cinema, drive-in theatres or videotapes before them. Anyway, let us leave this issue to researchers specialised in the exhibition sector and focus instead on contemporary documentary theory.

Source: Box Office Mojo, March 8, 2014.

Source: Box Office Mojo, March 8, 2014.

Aesthetic Functions and Modes of Representation

Just as the cinematic city has traditionally been understood as a simple representation of its real counterpart, non-fiction film has also been regarded as a reflection of reality. This approach, however, has shifted in the last decades to the extent that nowadays most film theorists address documentary as a discourse on the real, a line of argument constructed from visual materials that ultimately expresses a point of view on the historical world (see, for example, Nichols 1991: 111; Plantinga 1997: 83–6; Weinrichter 2004: 21–2, 2010: 270–1). In this sense, documentary film has developed several ways to fulfil its social function, as Nichols has pointed out:

Some documentaries set out to explain aspects of the world to us. They analyze problems and propose solutions. They try to account for aspects of the historical world by means of their representations. They seek to mobilize our support for one position instead of another. Other documentaries invite us to understand aspects of the world more fully. They observe, describe, or poetically evoke situations and interactions. They try to enrich our understanding of aspects of the historical world by means of their representations. They complicate our adherence to positions by undercutting certainty with complexity or doubt. (2001: 165)

This passage indirectly echoes the four tendencies or aesthetic functions attributed to documentary film by Michael Renov: ‘to record, reveal or preserve’, ‘to persuade or promote’, ‘to analyze or interrogate’ and ‘to express’ (1993: 21; 2004: 74). With the sole exception of the second one, the other three lead to what has been named the historical, identity and expressive value of film. In principle, the correspondence between the first tendency – to record, reveal or preserve – and the historical value is quite clear, as well as between the fourth one – to express – and the expressive value: regarding the former, Renov has explained that ‘the emphasis here is on the replication of the historical real, the creation of a second-order reality cut to the measure of our desire – to cheat death, stop time, restore loss’; while regarding the latter, he has stressed the importance of ‘the ability to evoke emotional response or induce pleasure in the spectator by formal means’ (1993: 25, 35) to establish any argument about the historical world. On the contrary, the relation between the third aesthetic function – to analyse or interrogate – and the identity value is a bit more complicated: Renov understands analysis ‘as the cerebral reflex of the record/reveal/preserve modality’ (1993: 30), which suggests that documentary film usually invites viewers to think and create meaning beyond what it shows. From this perspective, a place, an object, an event or even a manner of speaking may have an identity value in certain contexts, depending on the filmmaker’s aims and the audience’s sensibility.

These four aesthetic functions are not exclusive of a single type of documentary, and indeed they usually overlap each other. Nevertheless, some modes of representation are more appropriate than others to develop them: for instance, observational documentaries appear particularly suited to record live events, expository documentaries to persuade the audience, reflexive documentaries to analyse representational issues, and performative documentaries to express the filmmaker’s subjectivity. These pairings are actually an attempt to link Renov’s four aesthetic functions with Nichols’ six documentary modes of representation, which have become the best-known typology of non-fiction film since they were first defined more than two decades ago.

Initially, Nichols only distinguished four documentary modes: the expository, the observational, the interactive and the reflexive (1991: 32–75). Later on, however, he had to increase those four modes to six in order to identify more precisely the new subjective strategies that emerged at the end of the twentieth century: while the expository and observational modes remained the same, the interactive changed its name to participatory, the reflexive was divided into two different categories – the poetic and the reflexive – and finally the performative mode was added to the list (2001: 99–138). Both the original typology and its renewed version established a historical succession of modes in which the new coexist with the old without replacing them, as Nichols has always said (1991: 23; 2001: 33–4). His own table is still today the best way to summarise this evolution:

Documentary Modes

Chief Characteristics

(Deficiencies)

Hollywood fiction [1910s]:

fictional narratives of imaginary worlds

(absence of ‘reality’)

Poetic documentary [1920s]:

reassemble fragments of the world poetically

(lack of specificity, too abstract)

Expository documentary [1920s]:

directly address issues in the historical world

(overly didactic)

Observational documentary [1960s]:

eschew commentary and reenactment; observe things as they happen.

(lack of history, context)

Participatory documentary [1960s]:

interview or interact with subjects; use archival film to retrieve history

(excessive faith in witnesses, naïve history, too intrusive)

Reflexive documentary [1980s]:

question documentary form, defamiliarize the other modes

(too abstract, lose sight of actual issues)

Performative documentary [1980s]:

stress subjective aspects of a classically objective discourse

(loss of emphasis on objectivity may relegate such films to the avant-garde; ‘excessive’ use of style)

(Nichols 2001: 138)

This typology has somehow inspired this book’s division in three parts: just as these documentary modes represent ‘different concepts of historical representation’ (1991: 23), the formal devices discussed below represent, in turn, different ways of addressing a given historical process, the aforementioned transition from post-industrial city to postmetropolis. This time, there is no point in making a table to show the ascription of each case study to a documentary mode or another, because this information is not essential to understand the way these film devices depict urban space and create spatiality. Furthermore, almost no case study fits into one single category. The only exception would be

Los (James Benning, 2000), whose

mise-in-scène is clearly observational. In contrast, the rest of the case studies belong to several modes of representation at the same time:

London (Patrick Keiller, 1994) combines expository, observational and reflexive strategies;

News from Home (Chantal Akerman, 1977) and

Lost Book Found (Jem Cohen, 1996) are simultaneously observational and performative works,

Roger & Me has been regarded as an expository, participatory, reflexive and even performative documentary,

Porto da Minha Infância (

Porto of My Childhood, Manoel de Oliveira, 2001) and

My Winnipeg (Guy Maddin, 2007) are themselves hybrids of documentary and fiction, and so on, to name but a few examples. Knowing to which documentary mode a film belongs is certainly useful to analyse it, but there is a more important reason to take into account Nichols’ typology in this book: the evolution from expository to performative mode entails a shift from objectivity to subjectivity that also appears in the sequence formed by documentary landscaping, urban self-portraits and metafilm essays. In fact, the inherent tensions between objectivity and subjectivity have left a deep imprint on most case studies, which have been heavily influenced by the objectivity crisis and the subsequent subjective turn that non-fiction film has undergone over the last few decades.

The Objectivity Crisis

The idea of truth in documentary film has recently evolved beyond the concept of visible evidence, to the point that the strict authenticity of images no longer ensures the consistency of non-fiction discourse. Nowadays, the audience knows that truthfulness can be formally constructed through old rhetorical tricks: nobody believes that the omniscient voice of the classical expository mode is fully impartial and reliable, not even that the observational mise-en-scène is completely transparent. Since the 1970s, no expert or authority can guarantee anything anymore, because now any statement must come from personal, subjective experience. This is the reason why the concepts to which documentary film has historically been related – ‘fullness and completion, knowledge and fact, explanations of the social world and its motivating mechanisms’ – have been replaced by their opposites: ‘incompleteness and uncertainty, recollection and impression, images of personal worlds and their subjective construction’ (Nichols 1993: 174).

The so-called objectivity crisis has caused a sea change in the way contemporary documentary makers strive to produce a truthful discourse. Overall, they have resorted to three main strategies: the on-camera presence of the film apparatus, the use of the first-person singular and the systematic subjectification of discourse. The first strategy is directly related to the ethics of the gaze, which is currently based on the honesty and transparency with which filmmakers show the encounter between the real, the film apparatus and themselves (see Andreu 2009: 146). The second, in turn, involves a change of narrative position: ‘the filmmaker comes to the fore,’ Laura Rascaroli says, ‘uses the pronoun “I”, admits to his or her partiality and purposefully weakens her or his authority by embracing a contingent, personal viewpoint’ (2009: 5). Finally, the third strategy establishes a new argumentative logic: the more subjective a statement is, the more reliable it seems, because it is the truth according to the speaker; and the more the audience knows about the speaker, the easier it is to know if the speaker is trustworthy. This reasoning may border on tautology and even fallacy, but at least it warns that truth is never universal, but rather biased. Consequently, ‘subjectivity itself compels belief’, as Nichols has argued: ‘instead of an aura of detached truthfulness we have the honest admission of a partial but highly significant, situated but impassioned view’ (2001: 51).

By dispensing with its pretensions of objectivity, documentary film has simultaneously evolved into avant-garde and fiction, becoming a hybrid domain in which a wide range of devices coexist. The social perception of terminology itself reflects this expansive tendency: both the nominal and adjectival forms of the terms ‘documentary’ and ‘non-fiction’ have hitherto been used as synonyms, but ‘documentary’ is actually a much more specific genre, which traditionally entails some kind of narrative and an illusion of transparency, of realness; while ‘non-fiction’ is a much broader category open to non-narrative practices and all kinds of manipulations. One of the side effects of the objectivity crisis has been the confusion of both terms, because postmodern documentaries have thoroughly explored the legacy of ethnography, autobiography, self-portrait, self-fiction, diary films, essay films, travelogues, actualities, rockumentaries, mockumentaries, metafilmic practices and the entire experimental film and video tradition, including found footage film and video art among many other subgenres of non-fiction. This evolution is partly due to a change in the theoretical background of many documentary makers, who have studied in film and art schools instead of journalism ones: in their effort to differentiate documentary film from audiovisual report, they have borrowed some features from other non-fiction genres previously considered beyond the boundaries of documentary film. At this point, the more innovative works have developed a new relationship with the historical world, as suggested by Spanish theorist Josep María Catalá: ‘the proposals of contemporary non-fiction film go beyond the aesthetics of post-modernity, since they are not satisfied with the simple aesthetic expression of an idea on the world, as postmodern art usually does, but rather use aesthetics as a hermeneutic tool’ (2010: 290–1). Therefore, the postmodern challenge to the concept of truth has made way for a new process of sense-making in documentary film in which creativity and subjectivity play a major role.

Subjectivity in Documentary Film

The expression of subjectivity has been historically repressed in documentary film, but its exploration, according to Renov, has never contradicted ‘the elemental documentary impulse, the will to preservation’ (2004: 81). From the origins of cinema, the camera has always recorded images that are objective and subjective at the same time, because the act of filming involves two overlapping operations, as explained by Nichols:

To speak about the camera’s gaze is … to mingle two distinct operations: the literal, mechanical operation of a device to reproduce images and the metaphorical, human process of gazing upon the world. As a machine the camera produces an indexical record of what falls within its visual field. As an anthropomorphic extension of the human sensorium the camera reveals not only the world but its operator’s preoccupations, subjectivity, and values. The photographic (and aural) record provides an imprint of its user’s ethical, political, and ideological stance as well as an imprint of the visible surface of things. (1991: 79)

Postmodern documentaries have strengthened the subjective dimension of images, inverting the social perception of which component is considered more important: thus, after decades of debate on the scientific value of documentary film (see Winston 1993), the current paradigm suggests that the filmmaker’s subjective gaze usually precedes the camera’s objective gaze, at least in terms of sense-making. That is to say that the reasons to record an image always influence both the content and sense of that particular image, inasmuch as every camera – even surveillance cameras – operate according to a purpose previously established by a human being. The lowest level of subjectivity would then arise from the decision to film or not to film, to place the camera here or there, to cut the shot now or later, and so on up to replacing the third person with the first one. Once this step has been taken, the desire to preserve and to analyse remain the same, but the will to persuade is less common than the will to express ‘the filmmaker’s own personal perspective and unique view of things’ (Nichols 2001: 14).

In the last quarter of the twentieth century, subjectivity came to the fore in a series of minority cinemas made by women and men of diverse cultural backgrounds – mainly feminists, gays and lesbians, members of a particular ethnic minority and Third World citizens (see Nichols 2001: 133, 153; Renov 2004: xvii; Chanan 2007: 7). For all these people, subjectivity was, above all, a means to claim their otherness and counteract their usual misrepresentations in mainstream cinema: in their films, the filmmaker’s explicit presence was a basic strategy to deal with the historical world from a gender, ethnic or national perspective. Later on, many other documentary makers have embraced this approach – even white heterosexual men living in a First World country – because subjectivity has become ‘the filter through which the real enters discourse’ (Renov 2004: 176). As a result, everything has been subjectivised, including space itself, which is currently perceived and depicted according to filmmakers’ and filmed subjects’ personal ties with film locations.

Space in Documentary Film

After the commercial release of

London, British filmmaker Patrick Keiller stated in an article published in

Sight & Sound that ‘filmmaking on location offers the possibility of the transformation of the world we live in’ (1994: 35). In this regard, François Penz and Andong Lu have praised the ability of cinema to turn ‘even the most anonymous and banal city location [into] a consciously recorded space that becomes an expressive space’ (2011: 9). Nevertheless, the relationship between the audience and profilmic space – the space that is shown on the screen – varies from fiction to documentary film. The space of fiction, according to Michael Chanan, is always beyond our reach, even if it is a real place, given that ‘we cannot physically enter it and any connection with it is imaginary’ (2007: 79). In fiction, film locations may play themselves, stand for other places or simply symbolise certain kinds of places. We can visit them, but even so we will never be in their cinematic doubles, because they do not exist outside fiction. On the contrary, the space of documentary is ‘isomorphic with the physical reality in which we live our everyday lives’, that is, it does belong to the afilmic reality (‘the world that exists independently of the camera’) and consequently we can enter it whenever possible, because we are already within it (Chanan 2007: 79, 13).

Let us take as example the Dietrichson House in Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944), which also appears in Thom Andersen’s Los Angeles Plays Itself. In the first film, the façade was filmed on location and the interiors on studio sets, although their design remained fairly close to that of the original house. By juxtaposing both spaces, Wilder created a place that only exists on screen insofar as he shows it: the real house looks different indoors and the studio set lacks a real façade. In the second film, however, the house has lost its name – it must be remembered that the Dietrichsons were fictional characters – to simply become the house located at 6301 Quebec Drive, Los Angeles. Andersen shows it through a few architectural shots that recall the surveillance strategy described by Teresa Castro (2010: 145), thereby offering a synecdoche of the real place that invites the audience to visit it. This time, anyone can go there, adopt Andersen’s gaze and check that the off-screen space actually exists, because the house belongs to the same reality as the audience.

When filming buildings, Spanish architect Jorge Gorostiza has distinguished two main attitudes that insist on the differences between the space of fiction and the space of documentary: ‘the first attitude uses the cinematic apparatus in order to create new architectures or transform existing ones, usually as a space for developing fictions; while the second one places the filmmaker as a mere spectator who only describes the buildings without intervening in them, almost always through a documentary style’ (2011: xviii; my translation). These two ways of filming architecture can be extended to the whole urban space, giving rise to ‘creative geographies’ or, conversely, maintaining a ‘topographical coherence’ (see Penz & Lu 2011: 14). In the former case, the usual result is what I will term a ‘city-character’; while in the latter, the cinematic city remains faithful to a ‘city-referent’. These categories are not necessary anchored in the concepts of fiction and documentary, because they may indistinctly refer to both: on the one hand, a fiction film can depict the city-referent as faithfully as a documentary, even though its profilmic space remains a cinematic double of the original referent; on the other, many documentaries usually resort to the city-character in order to convey a particular perception of urban space and thus create spatiality.

The city-referent basically appears in those films whose profilmic space explicitly establishes a relation of continuity with real environments, regardless of whether the audience may enter it or not. Their images document urban space in past and present, preserving a visual record of its external appearance. The city-character, in turn, has more to do with both the city-text – ‘the product of countless and intermingled instances of representation’ – and the lived city – ‘the experience of urban life and of its representations that an inhabitant or a visitor may have’ – because it presents urban space as a subjective projection of the filmmaker’s or characters’ mood (see Mazierska & Rascaroli 2003: 237). These two categories are therefore complementary: the city-referent describes a place and the city-character interprets it. Considering that ‘cities in discourse have no absolute and fixed meaning’, as Colin McArthur has warned (1997: 20), their combined presence in the same work allows filmmakers to develop a subjective discourse on urban space – that is, to give it a particular meaning – without ever losing the sense of place. In the case of documentary film, in which profilmic space extends into afilmic reality, the union of the city-referent and the city-character is even more desirable than in fiction, because it provides the audience with a window to the historical world that is simultaneously an entrance to its inhabitants’ mind. This would be precisely the major virtue of most documentaries discussed below: they take us to a given time and place and make us understand its contemporary perception and socio-cultural connotations.

NOTE