The zero degree of mise-en-scène consists merely in establishing camera position and shot length, a simple matter of framing and duration. As early film pioneers were the first filmmakers to deal with these issues, all those works whose mise-en-scène choices are limited to these variables are usually described as ‘primitivist’. The origins of this aesthetic have been theorised by Noël Burch, who has developed the concept of the ‘Primitive Mode of Representation’ in order to group a set of early film styles characterised by ‘the autarchy of the tableau … horizontal and frontal camera placement, maintenance of long shot and “centrifugality”’ (1990: 188). Burch identifies these features with the ideal of ‘pure cinema’, a perception so widespread that all those film movements and formal devices attempting to recover the essence of cinema return one way or another to the conventions of early film. In this regard, observational landscaping is no exception to the rule, although its main influences are actually more recent: the avant-garde tradition of structural film and the modernist aesthetics of disappearance.

Structural film emerged in the US in the 1960s and was later developed in the UK. Its main representatives were American filmmakers Michael Snow, Hollis Frampton, Paul Sharits, Joyce Wieland, Tony Conrad, George Landow and Ernie Gehr, as well as British filmmaker-theoreticians Peter Gidal and Malcolm Le Grice. They all were primarily concerned with formal issues, to the point that the content of their works had to be ‘minimal and subsidiary to the outline’, as stated by P. Adams Sitney (2000: 327). According to this critic, the four main characteristics of structural film were ‘fixed camera position (fixed from the viewer’s perspective), the flicker effect, loop printing and rephotography off the screen’ (ibid.), but they seldom appeared together in a single film. The temporal logic of these works sought to achieve a real-time aesthetic, in which the screen time should be equal to the time of shooting, a formal choice that would later influence James Benning’s and Chantal Akerman’s works.

The aesthetics of disappearance, in turn, began with Michelangelo Antonioni’s early 1960s films, especially L’Avventura (1960), in which a character leaves the frame to never re-enter, and L’Eclisse (1962), in which the story itself dissolves into the cityscape. In this title, the closing sequence shows a few places where the two main characters had previously been and should have met again, but neither of them finally appears. Their absence is emphasised by a series of inanimate objects – a roller shutter, a hose, a zebra crossing, a house under construction or a small piece of wood floating in a bucket of water – which actually depict the eclipse of their feelings. According to Domènec Font, this way of filming the landscape establishes ‘a contiguity between characters and environments’ that relies on the correspondence between ‘cinematic, architectural and inner psychic space’ (2002: 311; my translation). Thus, in L’Eclisse, a house under construction on the outskirts of Rome symbolises both the new suburban landscape and the emotional emptiness of Italian bourgeoisie.

Antonioni’s aesthetics of disappearance has been taken up by a large number of filmmakers, including Wim Wenders, Théo Angelopoulos, Béla Tarr, Tsai Mingliang, Nuri Bilge Ceylan and Apitchapong Weerasethakul, among many others. The last one has even rewritten the closing sequence of L’Eclisse in Syndromes and a Century (2006), just as Richard Linklater and Lee Chang-dong had previously done in Before Sunrise (1995) and Poetry (2010), respectively, to show the absence or disappearance of the characters. Weerasethakul, however, quotes Antonioni to express an ontological emptiness that has recently been explored by Slow Cinema, which has been described by Jonathan Romney as ‘a cinema that downplays event in favour of mood, evocativeness and an intensified sense of temporality’ (2010: 43). In titles such as Sátántangó (Béla Tarr, 1994), La libertad (Freedom, Lisandro Alonso, 2001), Gerry (Gus Van Sant, 2002), Goodbye Dragon Inn (Tsai Mingliang, 2003) or El cant dels ocells (Birdsongs, Albert Serra, 2008), the aesthetics of disappearance has evolved into an aesthetics of emptiness in which there is no longer a story, but traces of a story. The narrative structure has been deprived of what we previously understood as beginning and end to focus instead on the middle, from which we have to deduce everything. Under these circumstances, the landscape often plays a key role as character, symbol or aesthetic motive, to the point that many of these films, despite being fictions, are also landscape films.

The ability of Slow Cinema – and by extension of observational landscaping – to depict the present time has been challenged by many critics who find these works a bit outdated. For example, Horacio Muñoz Fernández has said that ‘many landscape films are aesthetically romantic, topically anti-modern and theoretically wrong’ (2013; my translation). Previously, Antonio Weinrichter had already wondered what the point was of representing our experience in a world oversaturated with images by ‘replacing the zapping paradigm with pan or fixed shots at geological pace’ (2007: 72; my translation). Slowness, however, usually pursues an ideological agenda: to counteract the logic of spectacle, even at the risk of literally sending most contemporary viewers to sleep. For all those able to stay awake, the laconic

mise-en-scène of observational landscaping can document a place, convey its subjective experience and draw attention to the uses and abuses of the territory where it is located.

In these films, the frame is always the mediator between landscape, filmmaker and audience: its composition determines the audience’s experience of the landscape and also echoes the filmmaker’s experience while filming it. Hence, observational landscaping offers a blend of explicit objectivity – because the audience directly looks at the landscape – and implicit subjectivity – because the audience is placed in the filmmaker’s position. This double reading of landscape films ultimately explains why many white male structural filmmakers began to seek themselves in the landscape after the subjective turn in documentary film, as David E. James has explained:

The self-exploration and self-production of multicultural collectivities precipitated a crisis that was specifically acute for one group of filmmakers: white, heterosexual males. Excluded by definition from minority cinemas and damagingly associated with the putative hyperrationalism of structural film, for them neither the psyche of the individual protagonist nor its social projection as an expansive political movement was available as the basis of a counter-cinema. Since the story of heterosexual white men appeared to have been already told over and over again in the mainstream media – in fact, other groups agreed that it was the only story that patriarchal capitalist culture had ever told – they no longer had a socially viable counterstory to tell. Bereft of a history or recourse to a functional subjectivity, white heterosexual men typically turned from the inside to the outside and from time to space; if they found themselves, it was often in geography and films about landscape. (2005: 413)

James Benning is one of these filmmakers who have rediscovered themselves as ‘a perceptive being in space’, as Nils Plath has pointed out (2007: 201). In the 1970s, his main aesthetic referents were Andy Warhol, Michael Snow and Hollis Frampton (see Yáñez Murillo 2009: 81; Bradshaw 2013: 46), although his work later evolved into a

mise-en-paysage highly influenced by Land Art.

1 Like most landscape films, Benning’s work is based on the choice of the proper frame, within which he introduces ‘elements of plot intrigue, through marginal actions, and especially through soundtrack overlays’ (Martin 2010: 386). The resulting shots establish a constant play with offscreen space while showing a recurring iconography composed of ‘groups of cows, passing trains, emitting smokestacks, farmland being plowed, billboards, gunshots, oil wells (and) highways’ (Ault 2007: 106). Wherever Benning has been, he manages to convey the sense of place by extending the length of each shot: according to him, ‘place is always a function of time so one has to sit and look and listen over a period of time to get the feel of that place and see how that place can be represented’ (in Ault 2007: 91–2). Duration is then the key factor ‘to give you time to think about the image while you’re watching it (because) the way you think about the image will change over the course of its duration’ (Benning in Ault 2007: 88). In fact, looking at and listening to Benning’s films, they can be read in both personal and historical terms, as Julie Ault has suggested:

Benning’s work is as much a record of his consciousness in time and place, and therefore memory and how he incorporates time and place within himself, as it is concerned with society, industry, race, history, landscape, the Midwest, the American West, and America at large. (2007: 111–12)

This polysemy has to do with the open nature of the best landscape films, which can be as boring or significant as the audience wants. In Benning’s case, his habit of frequently filming his places of memory creates a cinematic geography endowed with multiple meanings: for instance, the Milwaukee neighbourhood where he was born and grew up has been depicted as ‘story, location, memory, history, imagery and metaphor’ (Ault 2007: 108) in five different films: Grand Opera: An Historical Romance (1978), Him and Me (1982), Four Corners (1997) and One Way Boogie Woogie / 27 Years Later. The last two – which are actually the same, as we will see – chronicle the impact of the urban crisis on Milwaukee and also express Benning’s affection for the depicted people and locations. Consequently, they are a prime example of how observational landscaping can simultaneously document place and mood, architecture and feeling, and, ultimately, urban change and passing time.

One Way Boogie Woogie / 27 Years Later: Documenting Time and Space

Milwaukee was once one of the great industrial metropolises in the United States, ranked the 11th most populous city in the mid-twentieth century. According to the 1960 Census, there were 741,324 people living in its urban area, but this figure has kept falling since then: 717,099 in 1970; 636,212 in 1980; 628,088 in 1990; 596,974 in 2000; and finally 594,833 in 2010. The 1970s seem to have been the worst time, when the population experienced a decline of 11.3% due to the industrial crisis and white flight, the same reasons that also affected other Rust Belt cities. This is precisely the period depicted in

One Way Boogie Woogie (1977), in which Benning documented ‘a specific social space at a specific moment in time’, as Barbara Pichler has highlighted (2007: 34).

This film was shot in Milwaukee’s industrial valley, an area where the filmmaker used to play as a kid, ‘hopping freight trains and fishing in the Menomenee River’ (Pichler & Slanar 2007: 248). By the late 1970s, however, the valley had been hit by the crisis, becoming a ruinscape that Benning decided to film: thus, in March 1977, he recorded images of factories, workshops, smokestacks, warehouses, quarries, storefronts, streets, roads and several street signs – especially the one-way sign – in order to capture and convey the sense of the place. These locations belong to work space instead of residential or leisure space, but they are deliberately filmed as haunted places: Benning shot them on Sunday mornings, ‘when no one was there’ (in MacDonald 1992: 235), because he did not want to idealise what was actually a romantic place for him.

Essentially,

One Way Boogie Woogie consists of sixty one-minute fixed shots that show sixty self-conclusive sequences without any clear narrative link between them. Some are purely contemplative, but most have a kind of internal microaction that increases or decreases the tension generated by the shot’s length. The dynamics are very simple, as Scott MacDonald has described: ‘the film allows us to become accustomed to a particular composition, then supplies an event that forces us to see the composition in a new way’ (1992: 221). Sometimes, these micro-narratives have an explanatory function, as when Benning’s daughter – filmmaker Sadie Benning, who was then four years old – rapidly crosses the frame from right to left while tapping on a metal fence with a wooden stick, thereby explaining the noise that has been heard since the beginning of the shot. At other times, certain objects suddenly enter the frame, such as a bottle, a stone or even a human foot. One way or another, there is always a play between foreground and background, image and sound, what is shown and what is implied: for example, the soundtrack includes extradiegetic sounds like radio recordings, peals of thunder over a shot of a blue sky or an approaching train that never enters the frame (

Image 3.1). These sound effects contrast with and comment on the images, suggesting mysteries to the audience through the interplay between the most basic elements of cinematic storytelling: framing, perspective, colour, lighting and sound.

Benning was aware of the anomalous nature of this film, so he decided to ‘make it a little more accessible by making it more like a game’ (in MacDonald 1992: 235–6). The micro-narratives are thus simple actions that convey complex meanings through scale distortions, unusual repetitions, strange image-sound combinations or stark contrasts between fixed frames and fluctuating sounds, a set of tricks that still draw the audience’s attention today, as the filmmaker himself has admitted:

When I look at … One Way Boogie Woogie, those tricks, and the little narratives I develop, are the least interesting parts of (the) film. What’s become more interesting to me … is how (it) matter-of-factly documented a particular social space; behind all my play with off-screen space, there is actually a documentation of that time and place, which has grown more interesting as those places have changed, even disappeared. But when I show One Way Boogie Woogie at retrospectives, and say, ‘I’m a little embarrassed by the little jokes’, I’m surprised at how much interest there is in that youthful play. (Benning in MacDonald 2006: 243)

The passage of time has favoured the film’s interpretation as an objective and subjective record of the urban crisis. The formal games do not distract the audience from this issue, but they actually reinforce it by abstracting the cityscape beyond its particular geographical location. In this regard, according to Barbara Pichler, ‘the images of Milwaukee … constitute a kind of meta-narrative about the development of the West’s urban industrial zone’ (2007: 34), a reading that opens the possibility of decoding the film as a commentary on this historical process. Let us take the final segment as example: shot 52 shows a car that cannot start, 54 a road where several phantom vehicles pass by, 55 a hidden drunk that suddenly reveals his presence, 59 a blue sky that contrasts with the noise of a nonexistent storm, and finally shot 60 a simulated car accident. Each of these shots refers to the urban crisis separately, but all together seem to express a warning message: the car that does not start could symbolise the inability of the industry to revive the economy, the phantom vehicles suggest the gradual disappearance of life in Milwaukee’s industrial valley, the drunk makes visible the social exclusion of a growing segment of the population, the contrast between the blue sky and the nonexistent storm could refer to the official discourse that denies the crisis, and finally the car accident closes the film with a metaphor for the plight of the Rust Belt. These meanings, however, are not in the images, but it is the images that make them possible. Benning encourages reflection by avoiding closed or literal meanings, leading some critics to misinterpret the film, as happened with shots 36 and 37 (

Images 3.3 &

3.5):

The image of the woman tied up has been criticized as sexist. The scene before that is the baby carriage rolling down the street, a reference to Eisenstein and the Odessa Steps sequence – a silly film joke – and in the background somebody with an accent is speaking about capitalism and the working class. The next shot is the woman who’s tied up and gagged, which I meant as a reference to the working class. (Benning in MacDonald 1992: 236)

Considering this context, the baby carriage would then refer to the downward trend of the economy – especially because this micro-narrative takes place in front of a building owned by the American Paper Company – and the woman tied up would obviously represent the working-class, which struggles for release. Nevertheless, when these two images were re-enacted in

27 Years Later, their meaning changed as a result of their adaptation to a new historical moment. The resulting film was not exactly a second part of

One Way Boogie Woogie, but rather its remake, a postmodern rewriting that updates its content and expands its discourse. Indeed, both works are currently shown together as a single one in a juxtaposition that establishes new connections between ‘memory, history, longevity, and discontinuance’, as Ault has pointed out (2007: 111).

2Benning has explained that he decided to re-film each individual shot in One Way Boogie Woogie as a vehicle ‘to revisit (his) past and to meet old friends again’ (in Slanar 2007: 176). Accordingly, in the new footage, the camera is roughly placed in the same spots, usually in front of the same people, although the exact replica is always impossible: many buildings had been demolished, some people had died, and even the physical appearance of the two twins who drink and smoke to the beat of a siren and a phone was no longer as identical as in 1977. These differences cause, according to Adrian Martin, ‘a massive material and conceptual displacement’ of the entire project, which has developed ‘completely different concerns’ regarding its original meaning (2010: 387). Thus, since 2004, the main subject of One Way Boogie Woogie / 27 Years Later has shifted from urban decay to ‘memory and aging’, as stated by Benning himself (in Pichler & Slanar 2007: 253).

Images 3.1 & 3.2: One Way Boogie Woogie / 27 Years Later, shot 22

The formal games in the original film have been replaced in its remake by the awareness of the passage of time, which is activated by the explicit comparison of equivalent images: for instance, shot 22, in which the filmmaker and a woman extended a thread across the railroad tracks, is repeated in the same place in the footage and in the same spot in the city, but the thread has been replaced by a measuring tape and the building in the background has disappeared (

Images 3.1 & 3.2). Nevertheless, the main difference between the original shot and its rewriting is the absence of suspense: the first time the audience sees this shot, most people believe that the approaching train heard on the soundtrack is going to enter the frame and cut the thread, but the second time everybody knows that the train will never appear, so its sound just recalls the previous suspense. Nostalgia and melancholia are therefore the dominant feelings, because the new footage basically shows that this cityscape has barely improved between 1977 and 2004. The atmosphere of decay is the same or even worse as in the 1970s, especially taking into account the disturbing signs of decline listed by Ault: ‘formerly active places turned dormant, absence, distinctive old buildings replaced by nondescript modern ones, and more barbed wire fences’ (2007: 110).

Melancholy is emphasised by overlapping the soundtrack of One Way Boogie Woogie and the images of 27 Years Later. The former had already been post-synched (see Benning in MacDonald 1992: 236), but the latter is directly out of synch due to the difficulty of adapting images to sounds instead of sounds to images. Consequently, many original elements remain in the soundtrack despite having disappeared in the images, like the crashed car in the last shot of the film. For this reason, the horn noise that closed One Way Boogie Woogie is no longer a warning message in 27 Years Later, but a reminder of the material and human absences in the new footage. The possibility of reusing the whole soundtrack of a pre-existing film was already explored by Benning in UTOPIA (1998), a film about the agricultural landscapes of Southern California in which he literally stole the English soundtrack of Ernesto Che Guevara, le journal de Bolivie (Ernesto Che Guevara, the Bolivian Diary, Richard Dindo, 1994). In that film, Benning ‘wanted to bring revolution to Southern California’ (in MacDonald 2006: 241), but this intertextuality has another purpose in One Way Boogie Woogie / 27 Years Later:

By using the same soundtrack twice I was able to provide the audience with a tool to map the second film back onto the first. This of course was necessary since many things had changed in the past twenty-seven years and not always did I reconstruct the narratives in the same exact way. (Benning in Ault 2007: 110)

The changes from one version to another can be accidental or deliberate, which allows the audience to reinterpret each shot. Let us examine a few examples: first, the chimney fire in shot 28 of

One Way Boogie Woogie becomes extinct in

27 Years Later, perhaps referring to the exhaustion of the industrial economic model; second, the factory in shot 50 is replaced by a McDonald’s restaurant, probably representing the decline of the industrial sector in favour of the service one; and finally, the forklift truck in shot 24 no longer carries a scrapped car but a shopping cart, an inspired joke on the passage from a production-based economy to a consumption-based one.

Images 3.3 & 3.4: One Way Boogie Woogie / 27 Years Later, shot 36

All these variations document urban change while commenting on the recent political-economic evolution, as in the aforementioned shots 36 and 37. The first one shows a baby carriage pushed by a man in a suit that crosses the frame from right to left, going up instead of down the street, whose appearance seem to have slightly improved since the 1970s – the pavement looks better, the grass is well kept and there is even a little tree, although the American Paper Company building has disappeared (

Image 3.4). Since the voice on the soundtrack says the same about capital and labour, shot 36 might be suggesting that some things have changed for the better, despite the vanishing of industrial activity. This interpretation is reinforced by the rewriting of shot 37, which makes explicit its reference to the working class: the bound and gagged woman stands in front of the camera, holding a sickle and a hammer with drooping arms (

Image 3.6). The new message is as parodic as contradictory: the working class has certainly been released, although it seems to have given up the active struggle, at least judging by the drooping arms.

Images 3.5 & 3.6: One Way Boogie Woogie / 27 Years Later, shot 37

The meaning of each shot is always open to interpretation, but there is no doubt about the aesthetic functions of this diptych: the first one would be, borrowing Michael Renov’s terms, ‘to record, reveal or preserve’ a particular cityscape, and the second one ‘to analyse or interrogate’ its historical and emotional evolution (1993: 21; 2004: 74). In other words, Benning’s primary concerns were to document a given place – his hometown – and to reflect on its perception over time, therefore depicting Milwaukee as both a place of memory and a synecdoche of the whole Rust Belt.

The California Trilogy: Mapping a Tortured Landscape

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Benning continued to film Midwest landscapes, but his geographical interest turned to the Southwest when he moved to Val Verde, California, to teach at the California Institute for the Arts in 1988. The first film in this new period was North on Evers (1991), a road movie that chronicles two motorcycle trips from Val Verde to New York and back to Val Verde, first taking the southern route and then the northern one. In these journeys, Benning crossed Utah, where he later filmed Deseret (1995) – ‘his first western’, as David E. James has dubbed it (2005: 422) – and also part of Four Corners – a work that explored the quadruple border between Utah, Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona. A year later, this westward shift was completed with UTOPIA, in which the filmmaker finally focused on the landscape of Southern California.

The geographical links between these titles are, according to Benning, the result of the influence that every film of his has on the following one (see MacDonald 2006: 242; Ault 2007: 105–6). In this sense, the California Trilogy emerged from a similar dynamic: first, El Valley Centro grew directly out of UTOPIA as a way of delving into the issue of land use; then, Los was conceived as its urban companion; and finally, Sogobi showed its opposite, wilderness, which is also understood as the origin of agricultural landscape. This transition from rural to urban and back to the natural environment has been interpreted by James as ‘a circular dialectic’, according to which ‘the industrial urbanity’ – if we start with Los – ‘generates its antithesis, the natural, which in turn generates the agricultural Central Valley as the synthesis between them – though it is itself being transformed more and more into the extended urbanity of Los Angeles, of Los’ (2005: 423).

The unity of the trilogy is achieved at three levels: first the geographical one, because the set of these films ‘aspires to represent the state as a whole’ (James 2005: 426); secondly the thematic, given that the entire trilogy deals with different forms of land occupation and exploitation; and thirdly the formal level, inasmuch as each part consists of thirty-five two-and-a-half-minute fixed shots followed by a detailed list of film locations, in which each shot is identified by its action, location and ownership. Thus, according to James, the trilogy suggests ‘the class divisions in the social systems that structure California geography’ by showing how ‘labor is divided and controlled by the wealthy and by corporations’ (2005: 427, 428). In

El Valley Centro, for example, the main landowners appear to be transnational companies engaged in the oil industry (Shell Oil Company, Chevron Corporation, Getty Oil, Texaco) or in freight transport (Southern Pacific Transportation Company, Union Pacific Railroad). The landscape is clearly ‘permeated by capital and labor’, as Claudia Slanar has noted (2007: 171), because every place has an owner and every natural resource has become a commodity, beginning with fresh water. Benning’s interest in water politics was already present in

UTOPIA, but he fully developed this subject throughout the entire trilogy:

In the Central Valley, corporate farms take advantage of two irrigation systems that were built with public money, one with federal money, one with state money. The corporations paid for none of the construction, but they take full advantage of it: 85 per cent of the water in California is used for farming; only 15 per cent is used for manufacturing and public consumption. And, of course, Los Angeles was expanded by stealing water from the Owens Valley. When I made El Valley Centro, I was very aware of the water politics, and I thought, ‘Well, when I make this urban companion, I’ll have to make a reference to how those politics continue from one place to another.’ So Los begins with water flowing into LA in the original aqueduct from the Owens Valley. And then, in Sogobi, I tried to show where the water comes from. (Benning in MacDonald 2006: 250)

Images of water infrastructures establish a visual and geographical continuity between the end of each part and the beginning of the next one: El Valley Centro opens with a shot of a spillway in Lake Berryesa and closes with an image of a pumping station in the California Aqueduct; Los begins with the Los Angeles Aqueduct and ends in the Malibu beaches, facing the ocean; and finally Sogobi starts with a rocky cliff in the California Sea Otter Refuge to then return to the spillway in Lake Berryesa. This loop closure allows the trilogy to be endlessly reproduced like a video installation which viewers can enter at any point, a formal decision determined by the structural rigidity of these works that actually serves to increase their meaning.

Benning is aware that the current perception of the California landscape is mediated by its multiple representations, whether as a non-humanised land reservation or a space of conflicting interests: the first perspective considers that wilderness must be preserved and protected from human erosion, while the second is rather concerned with its economic potential as a source of raw materials, developable areas, tourist attractions or even film locations. According to Benning’s opinion, the California landscape has been shaped by human activity for centuries, to the point that it has become ‘a tortured landscape’ (in Ault 2007: 92). Indeed, wherever he went while filming the trilogy, he always found the effects of the same process: man endeavours to tame nature, and nature responds by encroaching upon human space. From this perspective,

El Valley Centro shows the transformation of wilderness into rural landscape;

Los, the presence of nature in urban areas; and

Sogobi, the inability to find pure, unspoiled nature.

The way space has been produced in California, and especially in Los Angeles, has been discussed by a long tradition of boosters and critics, among which Mike Davis stands out. In Dead Cities and Other Tales, he summarised the main problems of the Sun Belt development model by talking about Las Vegas as a clone of Los Angeles:

Las Vegas has (1) abdicated a responsible water ethic; (2) fragmented local government and subordinated it to private corporate planning; (3) produced a negligible amount of usable public space; (4) abjured the use of ‘hazard zoning’ to mitigate natural disaster and conserve landscape; (5) dispersed land-use over an enormous, unnecessary area; (6) embraced the resulting dictatorship of the automobile; and (7) tolerated extreme social and, especially, racial inequality. (2002: 92)

In this excerpt, Davis related the expansion of this territorial model to the worsening living conditions of the underprivileged, an idea previously developed by Edward Soja in Postmetropolis: Critical Studies of Cities and Regions: ‘the new urbanization processes have built into their impact the magnification of the economic and extra-economic (racial, gender, ethnic) inequalities along with destructive consequences for both the built and natural environment’ (2000: 410). In the particular case of Los Angeles, the city’s adaptation to the new economic paradigm in the 1970s and 1980s came at the cost of sacrificing the social and territorial cohesion of its different communities: thus, while the closure of factories in the industrial corridor between South Central and Long Beach destroyed thousands of jobs in the African-American community, other activities based on fast, cheap and intensive work attracted hundreds of thousands of Latin American immigrants to the region. Under these circumstances, the imbalance between the economic status and the population ratio of the four main communities in the city led Davis to parody its workforce’s racial distribution as follows: ‘a white professional-managerial elite, a black public sector workforce, an Asian pettybourgeoisie, and an immigrant Latino proletariat’ (2002: 252–3).

These four communities do not have the same perception of the cityscape because their geographical distribution is neither uniform nor proportional to their number. Nevertheless, a particular community – high-income whites from the Westside – has taken advantage of its privileged socio-economic status to control the spatial representations of the city and thereby impose its cognitive map to the rest of the population: according to them, Los Angeles is a glamorous city of beaches and palm trees where white people can feel at home, instead of a multicultural postmetropolis with its own strengths and weaknesses. In order to counteract this media mirage, Benning depicted a completely different city in

Los (the most interesting film of the trilogy for this book) by focusing on those landscapes that best define the territorial model of Southern California: sprawlscapes, middle landscapes, non-places and banalscapes.

The first of these concepts, sprawlscape, refers to the landscape produced by ‘urban growth spilling out of the edges of towns’ (Ingersoll 2006: 3). Since the 1950s, especially in North America, many cities have doubled or even tripled their traditional extension through a process of mass suburbanisation, giving rise to a non-hierarchical succession of juxtaposed single-family houses, shopping centres and empty spaces organised according to their access to transportation networks. Soja has warned that this process ‘may be more advanced in Southern California than anywhere else in the United States’, to the point that it has actually become ‘a mass regional urbanization’ (2000: 141). The resulting cities have been praised by scholars like Reyner Banham because ‘all its parts are equal and equally accessible from all other parts at once’ (1971: 18), but this supposed spatial democracy may also cause problems of perception, as Kevin Lynch found out in the late 1950s:

When asked to describe or symbolize the city as a whole, the subjects used certain standard words: ‘spread-out’, ‘spacious’, ‘formless’, ‘without centers’. Los Angeles seemed to be hard to envision or conceptualize as a whole. An endless spread, which may carry pleasant connotations of space around the dwellings, or overtones of weariness and disorientation, was the common image. (1960: 40)

The sprawl has generated an increase in the middle landscapes within the city, a series of intermediate spaces between the built and natural environment that Lars Lerup has described as ‘unfinished, incomplete, waiting somewhere between development and squalor’ (2000: 158).

3 In such territory, which is neither urban nor rural, the main hubs are non-places such as airports, motorways, hotels or shopping centres; that is, those ‘spaces which are not themselves anthropological places and which … do not integrate the earlier places’, as defined by French anthropologist Marc Augé (1995: 78). The urban fabric surrounding them usually lacks a distinct identity, because it has been shaped from standardised models that can be reproduced anywhere. The ultimate expression of these interchangeable spaces has been termed banalscapes by Francesc Muñoz, a concept that identifies those ‘urban morphologies that are relatively autistic regarding the territory’ (2010: 190; my translation). This type of cityscape results from the recent thematisation and brandification of central and peripheral areas of the city, a process that seeks to transform each city into a competitive brand in the world market:

[Banalscapes] are a specific kind of cityscape that, despite being offered to city dwellers, have been produced to serve the interests, needs and requirements of the global economy. It is a hybrid cityscape that, on the one hand, has local character, because it retains some elements of the physical and social space, but on the other hand its appearance allows its standardised consumption by global audiences. This is the device whereby the final outcome of urban renewal looks similar everywhere. (2010: 195; my translation)

In

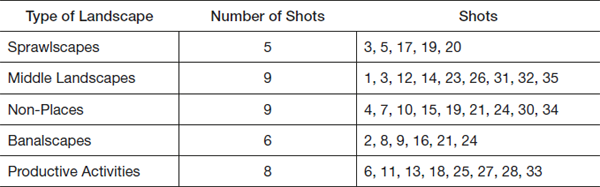

Los, Benning portrays Los Angeles as a set of scattered locations that generally fit into one of these four categories, as seen in

Table 3.1: the presence of a few sprawlscapes recalls the voracious expansion of the city at the expense of nature, the abundance of middle landscapes links the film with the rest of the trilogy, the numerous non-places confirm their ubiquity in the current urban fabric, and the inclusion of half a dozen banalscapes points out the emergence of new spaces of socio-economic power in West Hollywood, Bunker Hill, Orange County, the Financial District, Koreatown and even Chavez Ravine. A few images may be included in two different categories, and only ten from thirty-five shots (less than a third of the footage) do not correspond to any type of landscape since they are mostly devoted to productive activities.

Table 3.1: Los, distribution shots by type of landscape

NOTE: Shots 22 and 29 do not appear in this table because they respectively show a police squad and a cemetery. The full list of shots is available in

Appendix I, where they are identified by a number indicating their position in the footage.

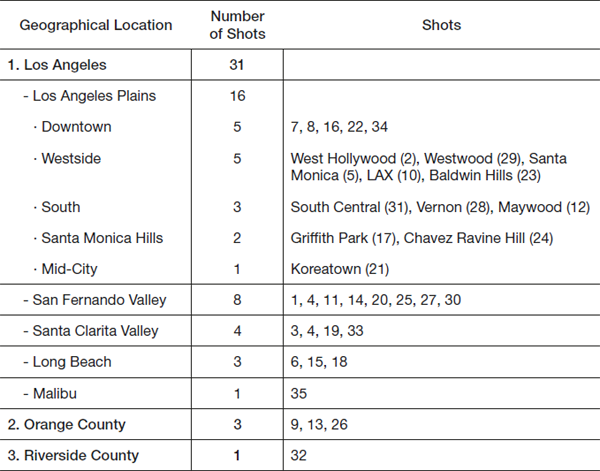

Table 3.2:

Los, distribution shots by geographical location

NOTE: Shot 4 was filmed in the Newhall Pass, the natural boundary between the San Fernando and Santa Clarita Valleys, so it has been counted twice.

The combination of these four landscapes mirrors the high level of entropy that characterised Sun Belt cities: the less organised the territory is, the less defined its identity will be, as suggested by Albert Pope in

Ladders (1996). In particular, the mass regional urbanisation in Southern California has led the Greater Los Angeles Area to expand into five different counties: Los Angeles, Orange, San Bernardino, Riverside and Ventura.

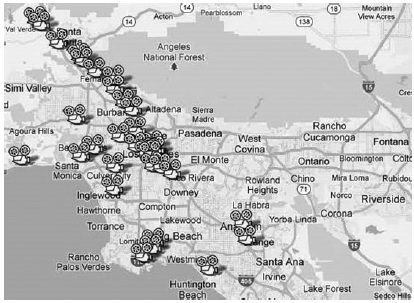

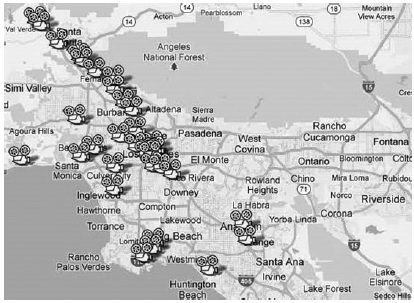

Los was almost entirely filmed in the first one, whose large land area – 4,083 square miles, or 10,570 square kilometres – allowed Benning to document a wide variety of places and landscapes, as seen in

Table 3.2 and

Map 3.1. It is important to note here that Benning’s vertex in the region is always Val Verde, his place of residence, which is located northwest of Los Angeles in the upper left corner of the map: that is the place from which he perceives the territory, whether the Greater Los Angeles Area, the Central Valley or the entire state of California. From there, he has to drive up and down the Interstate 5 to get anywhere, a perpetual movement that indirectly documents the car dependence in Sun Belt cities. Hence Benning’s landscape films can also be considered travelogues or even road movies.

The overrepresentation of higher-income areas in mainstream film – namely, Westside and Orange County – is counteracted in

Los by highlighting the demographic and territorial importance of the suburbs in the San Fernando and Santa Clarita Valleys, whose images correspond to almost a third of the footage (eleven shots). In comparison, there are more images from these areas than from Westside and Orange County together (eight shots) or from the pairing of Westside and Downtown (ten shots) in an explicit attempt to balance their real and symbolic presence in the everyday experience of the city for someone, like Benning, who lives in the northern suburbs. For this reason, Downtown is only represented by its two ends: on the one hand, businessmen and skyscrapers (shots 7 & 16; see

Image 3.7), on the other, homeless and prison (shots 8 & 34; see

Image 3.8). The suture point between these two worlds, the Broadway-Spring corridor, does not appear in the film, perhaps to emphasise the spatial polarisation of the area, which has been described by Soja:

With regard to jobs and housing in particular, this enclaved downtown is the site of two striking agglomerations representing the extremes of presence and absence. In the western half, consisting of the Civic Center complex of city, county, state and federal offices, and the corporate towers of the Central Business District and its southern extension around the Convention Center, is the densest single cluster of jobs in the polycentric postmetropolis. In the middle of the tiered enclaves that comprise the eastern half is Skid Row, on any given night the largest concentration of homeless people in the region if not the entire USA. With cruel irony, the homeless, with neither good jobs nor housing, probably outnumber the housed and employed residential population in the downtown core, despite concerted public efforts to introduce middle-class residents to live in the area and to control if not erase Skid Row. (2000: 252-253)

Benning consciously avoided most landmarks of the city because his main purpose was to restore the screen presence of the working class: faced with those discourses that stated its disappearance as a consequence of the industrial crisis,

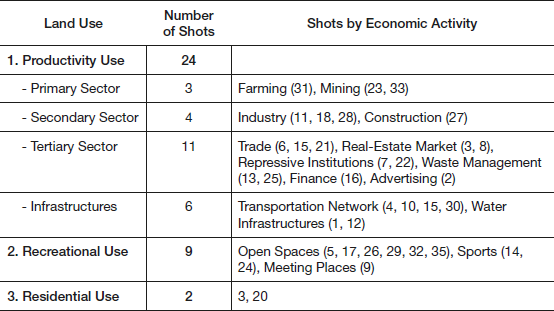

Los reveals a cityscape dominated by all kinds of workplaces where workers are metonymically represented. As seen in

Table 3.3, two thirds of the footage is devoted to productive land uses, among which tertiary sector activities stand out, from international trade to waste management. Some primary sector activities, such as farming and mining, still remain within the city, while industry appears to have undergone a slight decline: four shots of a total of thirty-five are not too many, but they at least show operating facilities in stark contrast with the ruinscape depicted in

One Way Boogie Woogie /

27 Years Later.

4 The six shots of transport and water infrastructures have also been counted as productive land uses, because they are essential for the circulation of raw materials and commodities, as water itself. Recreational land uses, in turn, correspond to those places where nature pervades the city, such as parks, beaches, cemeteries or playing fields, as well as meeting places like the Crystal Cathedral in Garden Grove, Orange County. Finally, only two shots represent residential land uses, but they perfectly summarise the dynamics of the sprawl from the first to the last stage (Images

3.9 & 3.10).

Images 3.7 & 3.8: Los, Arco Plaza (top) and Skid Row (bottom)

The image of the housing lots in Stevenson Ranch documents a landscape under construction that has just been taken from nature: it is the kind of middle landscape that precedes the explosion of the sprawlscape. Benning filmed this shot near his home in Val Verde, just on the edge of the urban frontier, where a new suburb was about to be built. These outlying communities bring the American myth of the frontier to the postmetropolitan context, consuming large amounts of land and consequently shaping spaces characterised by their deep unsustainability in functional, environmental, social and cultural terms, as Muñoz has warned (2010: 172). By showing the interregnum between natural and built environment, Benning did nothing but remind us that Los Angeles was, according to Davis, ‘the creature of real-estate capitalism: the culminating speculation … of the generations of boosters and promoters who had subdivided and sold the West from the Cumberland Gap to the Pacific’ (1990: 25).

Table 3.3: Los, distribution shots by land use and economic activity

NOTE: Shot 34 does not appear in this table because it shows homelessness in Skid Row.

Images 3.9 & 3.10: Los, housing lots in Stevenson Ranch (top) and a private residence in Encino (bottom)

The places depicted in Los are actually pieces of a historical narrative that accounts for the sustained growth of Los Angeles since the early twentieth century. Beginning with real-estate capitalism (shots 3, 8 & 20), its development was only possible thanks to the construction of a large network of water infrastructures (shots 1 & 12) and several regional transportation networks (shots 4 & 30). The local economy was fuelled by the creation of an artificial harbour in 1907 (shot 6), the establishment of the film industry in the 1910s (shot 2), the discovery of new oil fields in the 1920s (shots 18 & 23), the emergence of the aeronautical industry after World War II (shot 10) and the recent integration of the city into global capital networks (shots 8, 16 & 21). This account of continued economic progress also hides a counter-history of political scandals, social protests and violent uprisings, in which the resort to repressive institutions has been the usual way to maintain social order (shots 7 & 22).

All these places and activities are represented in

Los with a deep class-consciousness, thereby suggesting that social space has historically been produced in Los Angeles according to class, race and gender criteria (see James 2005: 427). The film is quite clear on this point: the spaces of power – Westside, Orange County, the Downtown Financial District and the San Fernando Valley – are white territories (shots 5, 9, 16 & 20), but most people who appear in the footage are actually Latinos, as already happened in

El Valley Centro (shots 7, 14, 17, 19, 20 & 31). Moreover, the choice of certain locations indirectly recalls a class- and race- specific history, as in the case of Bunker Hill (shot 8) and Chavez Ravine (shot 24), two former working-class neighbourhoods – the second one mainly populated by Mexican-Americans – that were razed to the ground in the 1950s to make way for, respectively, a new financial district and the Dodgers Stadium. Benning never makes explicit these historical accounts, because he is usually more interested in the present than the past of the cityscape. Nevertheless, this does not mean that he is not aware of the memorial value of his images. On the contrary, he films the present in order to document all that might disappear in the future, like the South Central Community Garden (shot 31), which is currently an empty plot of land.

5Within each one of these shots, Benning establishes a series of inner tensions to emphasise their condition as moving landscapes. His usual micro-narratives appear to have been choreographed, but this time he has explained that ‘it (was) only a matter of waiting for the right moment’ (in Slanar 2007: 169). The resulting effects may be the hypnosis induced by cyclic sequences or continuous flows, the surprise at unusual events, or the uncertainty of not knowing whether an action will be completed within the length of the shot. For two and a half minutes, the audience can explore the landscape with their eyes instead of their feet, as if they were on location with Benning himself. Accordingly, what is supposed to be an objective record of the cityscape actually becomes a subjective journey that links observational and autobiographical landscaping: the thirty-five shots of Los are actually thirty-five performances in which the filmmaker visits different parts of the Greater Los Angeles Area in order to record ‘how (he) felt at those places at those moments’ (in MacDonald 2006: 245). From this perspective, each film location in the entire trilogy is also a lived space that Benning wants to share with the audience:

I gravitate more and more toward … experiencing things by myself and perhaps make films about it because I also think that there is something marvellous about … sharing it with somebody. But if I would be making these films with somebody else along I couldn’t do it. I have to have that experience by myself to record it somehow – to actually see it. (Benning in Ault 2007: 90)

By being as observational as performative, the California Trilogy shows a landscape that is simultaneously objective and subjective, material and emotional, epic and lyric: it can be understood as a set of ‘sedimentary layers of historical events’ (Slanar 2007: 178), ‘a map of political denunciation’ (Muñoz Fernández 2011; my translation) or a geographical projection of the filmmaker’s self. That is to say that even the most detached filming device such as ‘observational landscaping’ can convey a personal view of the depicted space, inasmuch as the way someone looks at landscape implicitly reveals a way of being in the world and relating to it. Therefore, James Benning’s California Trilogy can be regarded as a film mapping of the territory’s ongoing transformations as well as a private diary of the filmmaker’s journeys and experiences through it. Since the images allow both readings, it is up to the audience to decide which film they want to see.

NOTES