After the 1973 crisis, the transition from an industrial economy to a service one caused a deep change in the socio-economic structures of Western countries: many factories closed and were relocated to other regions, dispensing with hundreds of thousands of skilled industrial workers who had to look for a new place for themselves in the service economy. Class-consciousness and intra-class solidarity were undermined by Ronald Reagan’s and Margaret Thatcher’s governments, whose neoliberal policies aimed to dismantle the welfare state in the United States and the United Kingdom respectively. Their aggressive opposition to free public services was interpreted by Gilles Lipovetsky as part of ‘the postmodern tendency to favour freedom instead of uniform egalitarianism, but also to hold individuals and companies responsible for themselves’ (1986: 134; my translation), a breach of the post-war social contract between corporations, unions and states termed ‘The Great U-Turn’ by Bennett Harrison (1988). These policies, according to Edward Soja, turned ‘what was initially described as a process of deindustrialization’ into ‘a polarizing of America that was intensifying poverty, decimating the blue-collar workforce, ruining once-thriving communities, and significantly pinching middle-class households as corporations sought new pathways to profitability’ (2000: 168). This gradual disintegration of the social fabric, along with the falling apart of effective agencies of collective action, have been considered by Zygmunt Bauman as ‘the unanticipated “side effect” of the new lightness and fluidity of the increasingly mobile, slippery, shifty, evasive and fugitive power’ (2000: 14). Inspired by French economist Daniel Cohen (1998), Bauman argued that the breaking down of the invisible chain that tied the workers to their working places was ‘the decisive, watershed-like change in life experience associated with the decline and accelerated demise of the Fordist model’ (2000: 58).

The workers’ change of position in the productive system involved the decay of their towns and neighbourhoods. In the luckiest cases, these places still preserved their architectural heritage after having been gentrified, but most were razed to the ground in order to make way for new developments, especially in the United States, where ‘the vindication of social and urban heritage did not go hand in hand’ (García Vázquez 2004: 70; my translation). Anyway, the original identity of these areas disappeared with their historical residents in those industrial and port cities that lost part of their population and former functions as regional centres in favour of global cities (see Sassen 2007: 111–12). In this context, two urban self-portraits such as

Lightning Over Braddock and

Roger & Me described the decline of the American Rust Belt cities in the 1980s through first-person narratives in which the directors themselves appeared onscreen: initially, Tony Buba and Michael Moore played the role of investigative reporters in what was supposed to be journalistic documentaries about the plight of their hometowns, but they soon became characters as important as the depicted cities by using their own body and subjectivity in order to convey the main concerns of their community. Such a way of addressing urban transformations in the American Rust Belt says more about the social perception of the process than about the process itself. Consequently, instead of providing the audience with an objective chronology of the events, these films basically show the emotional impact of the post-industrial crisis among the residents of these cities.

Roger & Me: The Industrial Town in Global Times

*

Michael Moore’s critical and commercial success has turned him, according to Paul Arthur, into ‘the public face of contemporary non-fiction cinema’ (2010: 106). Having won an Academy Award and a Palme d’Or in the 2000s – the first for Bowling for Columbine (2002), the second for Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004) – his best mise-en-scène and editing ideas actually come from his first documentary feature, Roger & Me, in which he already explored the quest structure, the practice of ambush interviews and the détournement of found footage. In this film, his well-known character – dubbed ‘a schlump in a ball cap’ by Sergio Rizzo (2010: 32) – appeared for the first time as ‘a combination of common citizen, investigative reporter, simple-minded buffoon and guerrilla performer’ (Oroz & Ambruñeiras 2010: 330). His close relationship with Flint, his hometown, is an important part of the character, since it allows him to introduce himself as part of the working-class rather than as a part of the elite (see Studlar 2010: 54). Indeed, Moore has regularly returned to Flint in later documentaries in order to reaffirm his film persona as an ordinary citizen concerned about his community.

Despite his constant allusions to his working-class origins, Moore has never been an autobiographical filmmaker but a first-person one: in his films, the expression of subjectivity is just a way to develop what Douglas Kellner has called ‘a unique genre of filmmaking, the personal witnessing, questing and agit-prop interventionist film that explores issues, takes strong critical point of view, and targets villains and evils in US society’ (2010: 100). This genre, according to Elena Oroz and Iván G. Ambruñeiras, has established ‘a bridge between the social documentary based on the principles of minimum interference adopted by American direct cinema … and the autobiographical and journal approach that had begun in the United States in the early 1970s’ (2010: 331), a combination so unusual for its time that critics have had much difficulty in locating

Roger & Me in Nichols’ schema of documentary modes. Miles Orvell has declared it ‘a hybrid of interactive and reflexive modes’, Matthew Bernstein has analysed its expository elements, and finally María Luisa Ortega has drawn attention to its performative strategies (see Orvell 2010: 128; Bernstein 1998: 397–415; Ortega 2007: 36–7). Contrary to what might seem, there is no contradiction in these three approaches, given that all of them point to what may be Moore’s main contribution to documentary film: his particular use of first-person narratives and ironic editing for updating the tradition of the socio-political documentary.

The best example of this device is the opening sequence of Roger & Me: the autobiographical approach is established by introducing the filmmaker himself as a character, summarising his origins, personality, wishes and current situation through a vertiginous editing of all kinds of materials, from industrial films to home movies. This beginning is already an accelerated self-portrait that serves to create a contrast between Moore and his antagonist, Roger Smith, the chairman of General Motors (GM) from 1981 to 1990. In this opposition, Moore embodies the everyman, that is, someone completely irrelevant, while Roger Smith is described as one of those people who run the world from the hidden controlling centre of which Guy Debord talked about at the time (1990: 9). The sequence also introduces the space where the confrontation will take place, Flint, which is depicted through a naïve account of its heroic past as a wonderful place to live, a discourse that seemed to be still in force in the 1980s.

In order to be perceived as part of the affected community by the audience, Moore proudly exhibits his working-class credentials: his father worked on the assembly line at the AC Spark Plug factory and his uncle took part in the historic GM Flint Sit-down Strike of 1936, the biggest milestone of the workers’ struggle in Flint. No matter that he himself has never directly worked for GM: his status as outraged citizen from Flint automatically gives him moral authority to level criticism at the company. The construction of his film character thus relies on the loss of his emotional referents, which are sometimes identified with places of memory, to the point that the description of Flint’s social situation and his own self-portrait go hand in hand.

Regarding the narrative structure, Roger & Me follows Moore’s political discourse and not a chronological order, sacrificing ‘historical accuracy in order to achieve the unity of satiric fiction’ (Orvell 2010: 135). The manipulation of facts and figures, as well as the way the filmmaker handles the power relationships in his interviews, have stirred up much controversy, starting with a famous conversation in which critic Harlan Jacobson accused Moore of tampering with the chronological sequence of events. In that interview, Moore defended Roger & Me by saying that ‘it’s not fiction, but what if we say it’s a documentary told with a narrative style?’ (in Jacobson 1989: 23), but even so he could not alleviate the harshest attack on the film: the following year, Pauline Kael described his discourse as ‘gonzo demagoguery’, denouncing that the film used ‘its leftism as a superior attitude’ and thereby encouraged the audience to ‘laugh at ordinary working people and still feel they’re taking a politically correct position’ (1990: 91). Gary Crowdus, in turn, took advantage of the title’s opposition to criticise the film, writing that ‘Roger & Me might have acquired a little more political bite if it had focused a little more on “Roger” and somewhat less on “Me”’ (1990: 30). This statement, however, simultaneously recognised and missed the point of the film, as noted by Arthur, who was one of its first advocates (see 1993: 128–31). A few years later, once the initial criticism turned into a growing appreciation, Orvell also hailed the film for its ability to deliver ‘the oblique truth of satire’ instead of ‘the straight truth of documentary’ (2010: 136).

Image 6.1: Roger & Me, Moore’s final confrontation with Roger Smith. Centre: Smith’s face. Right: Moore’s back.

Overall,

Roger & Me has been criticised for three main reasons: its lack of structure, its manipulation of chronology and its failure to create a coherent socio-political analysis (see Studlar 2010: 53). Nevertheless, beyond the debate on authenticity and accuracy, this documentary did manage to convey the local perception of Flint’s urban decay, equating Moore’s failure to interview Roger Smith with the feeling of powerlessness experienced by many laid-off workers at the time (see Ortega 2007: 36; Orvell 2010: 138).

1 Although the credibility of

Roger & Me has been seriously damaged since the documentary

Manufacturing Dissent (Rick Caine & Debbie Melnyk, 2007) revealed that Moore actually did get an interview with Smith but finally chose not to include it in the final editing (see Bernstein 2010: 7), the metaphorical meaning of the chase after Smith does not change, because it is based on the political impotence of individual subjects to face corporate power (

Image 6.1). In this sense, the solitude and isolation of the autobiographical self becomes a symptom of the social fragmentation characteristic of post-industrial capitalism, as Jim Lane has explained:

[Moore’s] own representation as the autobiographical narrator in search of answers of Roger becomes a disabled self, armed with the critical apparatus to understand what is going on in his hometown but incapable of effecting change as much as the working people whom [he] indicts. The film becomes a self-portrait of political impotence and futility within the larger frame of social and economic conditions with which the subject maintains a perplexing autobiographical connection and moral detachment. (2002: 138)

When Roger & Me was theatrically released, Reaganomics had completely transformed the US labour market, shattering the idea of a life-long job in a secure company. Later on, Bauman warned that ‘in the world of structural unemployment no one can feel truly secure’, because there are no ‘skills and experiences which, once acquired, would guarantee that the job will be offered, and once offered, will prove lasting’ (2000: 161). The new labour paradigm imposed uncertainty through flexibility, replacing ‘secure jobs in secure companies’ by ‘the advent of work on short-term contracts, rolling contracts or no contracts, positions with no in-built security but with the “until further notice” clause’ (2000: 147). Under these circumstances, the individual has to cope with ‘a life without protection, without class culture, without a collective framework [and] without a political project to transform the world’, as Gilles Lipovetsky and Jean Serroy have highlighted (2009: 192; my translation).

Such a situation, according to Bauman, was caused by a sea change in ‘the managerial science’ of capitalism: initially, the system focused on ‘keeping the “manpower” in and forcing or bribing it to stay put and to work on schedule’, but after the post-industrial crisis it was rather concerned with ‘letting “human-power” out and better still forcing it to go’ (2000: 122). Moore denounced these practices in

Roger & Me without aiming at the macroeconomic system yet, as his

Capitalism, A Love Story (2009) would do two decades later. On the contrary, by focusing on Flint’s situation as an example of what was happening in the Rust Belt, he captured the deep disorientation of his own community: the film thereby emphasises the workers’ lack of historical consciousness and perspective in the face of the bitter defeat that they were suffering, showing their alienation with junk television products and pop culture sponsored by GM, such as the Newlywed Game – a TV programme hosted by an anchorman born precisely in Flint, Bob Eubanks – or Pat Boone’s and Anita Bryant’s concerts.

These kinds of celebrities – including Miss Michigan 1987 – were the people who went to Flint to lift the spirits of the unemployed. Their interventions show how the public debate on the crisis was simplified to the point of banality: most of them simply repeat that the best way to overcome the recession is to take initiative and stay positive, a naïve discourse that ignored the serious impoverishment of the working class. By letting them speak, Moore ridicules the ‘bread and circus’ policy that GM offered to Flint as only compensation after eight decades of active service, also warning that the promises made during the post-war economic boom can no longer be fulfilled within the neoliberal paradigm. In fact, throughout his entire film career, Moore has denounced that the alliance between large corporations and Republican administrations has betrayed the ideals of the American Dream, such as a decent job for life, a home of one’s own or a public helth care system, the issues respectively addressed in Roger & Me, Capitalism, A Love Story and Sicko (2007). For this reason, his identification with the working class has been interpreted by Gaylyn Studlar as ‘a nostalgic desire for a return to the past’ (2010: 62).

Moore, however, also loves the same cultural debris that he criticises, at least as source materials: among a wide variety of footage related to Flint,

Roger & Me includes home movies, newsreels, TV news clips, automotive TV commercials, clips from industrial training films and excerpts from studio-era Hollywood. All this visual waste is mobilised, according to Arthur, ‘for purposes of editorial comment as well as illustration of factual statements’, thereby producing not only ‘humorous asides’ but also decentring ‘effects of a unified enunciative presence’ (2010: 112). The outcome seems a film adaptation of the Situationist

détournement, a practice that consists in ‘the integration of present or past artistic production into a superior construction of a milieu’ (Knabb 1981: 45). Moore’s main influence was probably

The Atomic Cafe (Jayne Loader, Kevin Rafferty & Pierce Rafferty, 1982), a compilation film that used humour and irony to distort the original meaning of the footage.

2 Both documentaries would be what Sharon Sandusky has called a ‘toxic film artifact’: a work that exposes the dangerous engineering and manipulation that the original material already had in its original context (1992: 6). These kinds of compilation films usually recycle footage from the 1950s, a period in which America ‘was constructed in the media as a culturally specific domain of family values, democracy, and free enterprise with the small town and suburban nuclear family as its focal point’ (Russell 1999: 242). Moore, in particular, goes back to that Golden Age in search of images that recall its unfulfilled promises: he applies the same demystified logic to both old and contemporary materials in order to subvert his opponent’s message while promoting his own, as Situationists did by means of

détournement (see Coverley 2010: 96).

Humour consequently pervades the film, producing ironic dichotomies that further Moore’s political argument: in one of the most significant sequences of Roger & Me, he uses the musical score as counterpoint to images, playing the Beach Boys’ song ‘Wouldn’t It Be Nice’ over several tracking shots that depict the worst effects of urban decay – business closures, loss of population, dilapidated buildings, empty houses and a worrying increase in the rat population. The choice of this particular song is not arbitrary, but it was suggested by a friend of Moore’s who suffered an anxiety attack as result of his fear to be fired for the umpteenth time. Thus, while images provide visible evidence of the effects of the crisis on the cityscape, the upbeat lyrics of ‘Wouldn’t It Be Nice’ contrast with the friend’s depression and also parody all those positive messages unable to improve Flint’s situation. This type of détournement – placing a song out of its original context as ironic commentary – entails the expression of two different discourses, one based on well-intentioned statements and another on their factual verification, allowing the audience to build a new meaning through their comparison. Like documentary landscaping, this device provides a critical tool to challenge the official discourse on urban change, given its implicit suggestion that this process might have developed otherwise.

The lack of prospects in Flint led its residents to demobilisation, as revealed by the statements of politicians and trade unionists included in the film: during the parade that commemorates the Great Flint Sit Down Strike, the president of the UAW – United Auto Workers – admits that ‘we have to accept the reality that [the plants] are not going to remain open’. Despite the rejuvenation attempts undertaken by local authorities, which are also parodied in the film, the industrial city where Moore grew up was disappearing in the 1980s, at least as he remembered it: according to US census figures, the population of Flint dropped from 159,611 residents in 1980 to 140,761 in 1990, a decrease of 11.8%. To make matters worse, this downward trend had already started in previous decades and has spanned until today, causing the loss of almost half of its population: from 196,940 residents in 1960 to the current 102,434 registered by the US census in 2010. Like other Rust Belt cities, Flint should have been ‘nice’, but the post-industrial crisis spoiled it, to the point that Money magazine chose it as the worst of three hundred urban areas to live in the United States for ‘its high crime rates, weak economies and relatively few arts and leisure activities’, an affront to the local self-esteem also included in the film.

This depressive

zeitgeist is depicted by recording Flint’s endangered cityscape and constructing a nostalgic discourse on its loss – the loss of a place of memory, but also the loss of what it symbolised. For example, by filming the last truck made in the Flint factory, Moore and his crew also captured the workers’ contradictory attitude towards their redundancy: most employees clapped their hands, perhaps to present their last respects to the factory and their old jobs, or simply to encourage themselves, but there is a man who verbalises the collective concern: ‘

What’s everybody so happy about? We just lost our jobs!’ Unfortunately, their alternatives of a new job, as suggested in the film, were not exactly very promising: the first was migrating to the Sun Belt, which threatened community survival; the second, self-employment, which rarely had the desired success; and the third, retraining, which almost always entailed a deterioration in working conditions.

The tendency to frequently move from one region to another has to do, according to Kevin Lynch and Michael Southworth, with the American way of life and ‘the expression of our free spirit’ (1990: 95). These authors warned that ‘regional shifts may be accounted favorable only when costs are paid by the migrant enterprises that benefit, when the old and the poor are not unwillingly left behind, and when social and psychological ties are not unnecessarily broken or traditions lost’ (1990: 169). The massive migration from the Rust Belt to the Sun Belt in the 1980s, however, did not always follow this advice, especially in those cases in which it was actively encouraged by the Reagan administration as the only solution to economic stagnation: ‘The 1980 President’s Commission for a National Agenda proposed that national policy should encourage this mobility, rather than seeking to check it. […] Present subsidies to declining places, in their opinion only trap the poor, since they tempt them to stay and survive, when they might move and prosper’ (1990: 95). Faced with this logic, Roger & Me shows the other side of this policy: as so many people voluntarily left Flint in the mid-1980s, the truck rental companies did not have enough vehicles to provide their services to the most needy, beginning with evicted families. Moore’s interest in this particular side effect of the internal migration policy is coherent with his personal decision to return to Flint after the failure of his own move to San Francisco, because he wants to tell the story of the people who have no choice but to stay in Flint despite the evident lack of prospects.

Regarding attempts at self-employment, the film highlights the absurdity of many situations in order to discredit the neoliberal praise of entrepreneurial attitude. Among other individual cases, Moore follows the stories of Rhonda Britton, a woman who sells rabbits as pets or meat, and Janet K. Rauch, a former feminist turned distributor for Amway – a direct-selling company specialised in health, beauty and home care products. Considering Moore’s love for unsubtle metaphors, Rhonda’s rabbits seem to symbolise the awful fate of the working class – becoming pets/slaves or dying to feed your owner/employer – while Janet’s obsession with winter or summer colours is shown as proof of feminism’s defeat by the conservative backlash of the 1980s.

The retraining stories are not much better either. Moore tells us how ex-auto workers were hired as prison guards in jails that held former colleagues turned criminals by unemployment, while others found jobs in the fast food sector, just to immediately lose them due to their inability to keep up with the hectic pace of the kitchen. According to a Taco Bell manager, ‘many [workers] say that this is a lot of hard work because assembly work is easy. […] [Instead], fast food demands a fast pace because we want to present a food item within so many seconds, if we can do it. […] Some of them just couldn’t develop that speed.’ This comment bespeaks the social stagnation of industrial workers, unable to adapt to the requirements of the service industry of the 1980s. In light of this situation, the only man with ‘a secure job’ that Moore could find in Flint did not precisely work for community building, but just the opposite: the main activity of sheriff’s deputy Fred Ross was to evict those who could no longer pay the rent.

The desperation of the unemployed contrasts with the upper classes’ lack of social conscience. Moore asks affluent people about their opinion on the crisis, and their answers reveal that they sincerely believe that the economic recession can be overcome with assertiveness. By editing their most unfortunate statements, Moore puts on display the class privilege, racism and sexism of those who are apparently not affected by the crisis, as has been noted by Douglas Kellner (2010: 84), thereby revealing their ‘steadfastly held sense of superiority over and indifference to the suffering of their fellow citizens’ (Studlar 2010: 61). The ruling class, however, has also been conditioned by neoliberal policies since the 1980s, to the point that any contemporary government, no matter its ideology, has to adapt its decisions to the demands of corporate power, even when they are not appropriate for their particular situation, as Bauman has explained:

A government dedicated to the well-being of its constituency has little choice but to implore and cajole, rather than force, capital to fly in, and once inside, to build sky-scraping offices instead of staying in rented-per-night hotel rooms. And this can be done or can be attempted to be done by (to use the common political jargon of the free-trade era) ‘creating better conditions for free enterprise’, which means adjusting the political game to the ‘free enterprise’ rules – that is, using all the regulating power at the government’s disposal in the service of deregulation, of dismantling and scrapping the extant ‘enterprise constraining’ laws and statutes, so that the government’s vow that its regulating powers will not be used to restrain capital’s liberties become credible and convincing. (2000: 150)

In the case of Flint, the best example of how corporate power kidnapped the local government was the promotional campaign to attract tourists and investors in the mid-1980s, a project that included the building of a luxury hotel, a shopping centre and a theme park dedicated to the automotive industry, AutoWorld, as well as the spread of institutional advertising on how to welcome visitors. The main idea, according to Miles Orvell, was ‘the creation of an economy of the “simulacrum”’, in which the production of consumer goods was replaced by ‘a story about the production of consumer goods’ (2010: 139). This episode is addressed in the film through another

détournement in which Moore juxtaposes footage of this promotional campaign with its poor results: as tourists never came, the hotel was sold, the shopping centre remained half empty and AutoWorld closed in January 1985, only six months after its opening in July 1984. Meanwhile, the only business that seemed to succeed in Flint was a company that made lint-rollers, Helmac Co., which is mentioned by GM lobbyist Tom Kay as an example of the business opportunities that were still in Flint. Thereupon, Moore inserts a couple of shots of lint rollers and compares this product with the auto industry, reminding viewers of the huge scale differences between both activities. By ridiculing his opponents’ messages again, Moore turns Kay’s suggestion into a fallacy before the audience, who takes sides with the filmmaker not only because he may sometimes be right, but mainly because his arguments are more fun.

To sum up, Moore’s personal involvement with the community remains the key factor in conveying the bitter experience of industrial decline. The choice of self-portrait as supporting subgenre for socio-political documentary reinforces his arguments, inasmuch as it creates an emotional link between subject and object. This does not mean, however, that ‘Moore is Flint’ and ‘Flint is Moore’, paraphrasing Rudolph Hess’s ominous speech about Hitler and Germany in Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will, Leni Riefenstahl, 1935). On the contrary, Moore introduces himself as an ordinary citizen who wants to explain the problems of his community to a wider audience, talking from below and not from above, that is, from the residents’ perspective instead of from a position of power. Accordingly, Roger & Me documents the time when the people from Flint realised that ‘GM was not Flint’ and therefore ‘Flint was not GM either’, despite having been its birthplace in 1908. Moore certainly represents ‘a private interest’, as the workers’ spokeswoman says when she refuses to make any statement to the camera, but at least it is his own one: that of a first-person filmmaker who attempts to expose an awful truth (GM no longer cares about Flint) while simultaneously exposing his own self (who does care, greatly).

Lightning Over Braddock: A Rustbowl Fantasy: The Big Fish in a Little Pond

Tony Buba might have inspired Jim Lane’s definition of ‘autobiographical documentarist’: he is ‘a filmmaker working in anonymity, at a very local level, under low-budget constraints’ (2002: 4). Contrary to Michael Moore, Buba is rarely known outside the United States, and he can only be considered a celebrity in the Pittsburgh area, where his hometown, Braddock, is located. His urban self-portrait, Lightning Over Braddock: A Rustbowl Fantasy, anticipated some of the features popularised by Moore, such as the aesthetics of failure, personal politics or ironic selfhood, although its main novelty was probably the inclusion of fictional fantasies within the non-fiction context (see Lane 2002: 139). In this film, Buba assumes a wide variety of roles, ‘from recorder to social actor to scripted fictional character to commentator’, as Paul Arthur has pointed out, but all of them can be summarised in the following two: on the one hand, Buba is Braddock’s official chronicler, its ‘bard’, as John Anderson (2012) has called him; while on the other he is the main subject of this documentary, at least as much as Braddock itself (Arthur 1993: 131).

Both roles are established from the very beginning of the film. Its opening shot is an image of a postcard sent by Buba to his brother Pasquale, which reads as follows: ‘

Dear Pat,

Carrie Furnace is now closed. The Homestead Mill might be next. I’m glad Dad retired when he did. Starting a new film on mill closings, might need your help. Take care. Your brother.’

3 Like the beginning of

Roger & Me, these lines introduce the filmmaker as the main character of the film (

Image 6.2), reveal the setting (his hometown) and the subject (its decline) and consequently locate

Lightning Over Braddock between the traditions of socio-political documentary and domestic ethnography. Nevertheless, the blend of collective and individual issues is deeper here than in

Roger & Me, to the point that it is never clear if the self-portrait is simply a device for depicting the postindustrial crisis, as it was in Moore’s documentary, or if the crisis is rather a backdrop against which to develop the self-portrait.

Image 6.2: Tony Buba, posing with Carrie Furnace in a publicity still of Lightning Over Braddock

The combination of a macro and micro approach continues in the following sequence, in which Buba alternates landscape shots of the Pittsburgh area with Braddock street scenes while providing information about the crisis. Here is the transcription of the introductory commentary:

The Pittsburgh renaissance of the 1980s was deceptive. High technology was the corporate buzzword. High technology means Carnegie Mellon University, computers, software contracts. To corporate leaders, high technology meant the chance to build new factories in El Salvador, South Korea, the Dominican Republic. Anywhere where there was a friendly, repressive government and the promise of no unions and low wages. Office buildings rose, factories were razed. Towns went bankrupt. Water became undrinkable. Infant mortality rates among blacks were higher than in Third World countries. Once-proud communities were reduced to playing the state lottery in the hopes of keeping their towns alive. Over a hundred thousand people moved out of the area. Homes were lost. Suicides increased. All of the mill towns were hit hard. One of the towns hardest hit was my hometown, Braddock. Braddock is a small mill town six miles from Pittsburgh. In Braddock, the unemployment rate was thirty-seven percent. The per capita income was less than five thousand dollars. Loans were taken out to meet the town’s payroll. These were hard times. There was a lot of poverty, a lot of anger, and a lot of daydreaming.

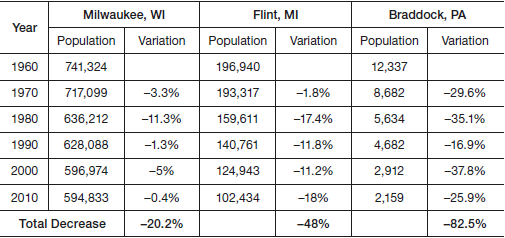

These lines could also refer to Flint, but Braddock’s situation was even worse: on 15 June 1988, it was declared a ‘distressed municipality’, that is, a town in bankruptcy, a status from which it has not recovered yet (see Stewart 2012). A quick overview on the historical evolution of its demographic statistics reveals an advanced level of urban decay: in the three decades before the commercial release of Lightning Over Braddock, the town lost 62% of its population, going from 12,337 residents in 1960 to 4,682 in 1990. Currently, according to the 2010 Census, Braddock only has 2,159 inhabitants. The following table may help to see the big picture of American Rust Belt cities’ depopulation after the 1960s, taking as examples the three cases referred to in this book: Milwaukee, Flint and Braddock, each one representative of a particular film – One Way Boogie Woogie / 27 Years Later, Roger & Me and Lightning Over Braddock – and of a particular type of city – the centre of a metropolitan area, a medium-sized city and a small mill town.

Source: US Census Bureau.

This chart shows that the worst population decline occurred in the 1970s, when James Benning shot One Way Boogie Woogie. In the 1980s, the percentages eased, but the same negative trend remained, creating a feeling of irreversible deadlock when Moore and Buba made their films. With the exception of Milwaukee, the situation does not seem to have improved in the 1990s and 2000s, especially in the case of Braddock, which lost even more population in percentage terms in the 1990s than in the 1970s. In order to present the particular case of Braddock within a national context, Buba sometimes echoes macroeconomic figures in his film, as when he comments that ‘90% of the baby-boom generation has a lower standard of living than their parents’ or when he films the following statistics in a local bulletin board:

For every 1000 manufacturing jobs lost, we lose: 1000 service jobs, 17 doctors, 17 eating places, 13 food stores … 11 gas stations, 6 clothing stores, 5 dentists … 3 auto dealerships, 2 hardware stores, 2 drug stores … 2 auto accessory stores, 1 jewellery store, 1 sports store [and an] unknown number of teachers and government workers. These statistics are from the US Department of Commerce and the Federal Office of Budget and Management.

All this information awakes the nostalgic desire to return to better times, whether in terms of quality of life or social commitment. As the 1970s were not precisely a time to remember fondly, Braddock residents had to go back to previous decades to find something to be proud of: towards the end of Lightning Over Braddock, an old man recalls the successes of the workers’ struggle in the 1930s and encourages young people to ‘take to the streets’ again. This discourse is assumed by Buba himself, who ironically pretends to be a modern political filmmaker instead of a postmodern one: ‘With statistics like this’, he says over images of the Saint Patrick’s Day parade, ‘you’ll think there’ll be mass demonstrations: people taking to the streets. But there didn’t seem to be much interest in saving manufacturing jobs. I thought this is a perfect time for a political filmmaker. I can make the film that will raise consciousness! People will take to the streets.’

There is a good deal of political rallies and demonstrations in the film, but even so Buba is far from fulfilling his stated intentions: before raising the consciousness of the audience,

Lightning Over Braddock awakes his own one, compelling him to face his feeling of guilt for taking advantage of the situation. ‘

The ironic thing,’ he admits in the commentary, ‘

is [that] as Braddock and the Monongahela Valley declined, my fortune increased.’ This confession, according to Lane, questions those filmmakers ‘who use the plight of others to promote their own careers’ (2002: 142), that is, anyone who crosses the boundary between social documentary and porno-misery.

4 Thus, when it is assumed that the film should go deeper into Braddock’s case, it instead exposes the contradictions of the filmmaker by including the footage of one of Buba’s appearances on television: a television portrait within a film self-portrait.

Considering that Buba was – then and now – a complete unknown, this footage allowed him to summarise his film career, from his first short documentary,

J. Roy: New and Used Furniture (1974), to his modest success,

Sweet Sal (1979), both included in the collection

The Braddock Chronicles (1972–1985).

5 His commentary, however, does not sound as proud as it might: ‘

My exposure on TV was directly proportional to the number of layoffs,’ he says. ‘

The one question I was always asked was “do you ever think about moving?” Of course, the one answer I never give is that “no, I like being a big fish in a little city”.’ This is Buba’s drama: he would like to be famous around the world, but he is actually satisfied with being famous in Braddock. Therefore, what seemed a shameless act of self-promotion turns into a sample of the possibilities that first-person filmmaking opens for a secondary revision of our memories (see Renov 2004: 114). Indeed, Buba’s critical remarks on his media persona are a prime example of post-modernity’s narcissistic humour, as Gilles Lipovetsky has described by talking about Woody Allen’s films:

The self becomes the prime target of humour, an object of derision and self-predation. The comedy character no longer uses the burlesque, as Buster Keaton, Charles Chaplin or the Marx Brothers did. Its humour does not come from the failure to adapt to the logic nor from its subversion, but from self-reflection: a narcissistic, libidinal and corporeal hyperawareness [of its own self]. The burlesque character was unaware of the image that it offered to the others, it made people laugh despite itself, without observing itself or seeing its performance. The absurd situations that it caused triggered the comedy according to an irremediable mechanism. On the contrary, Woody Allen makes people laugh by means of narcissistic humour, endlessly analysing himself, dissecting his own ridicule, introducing his devalued self mirror to himself and the audience. (1986: 144–5; my translation)

In this quotation, where Lipovetsky wrote ‘Woody Allen’ it is possible to read many other names, such as ‘Tony Buba’, ‘Ross McElwee’, ‘Nanni Moretti’ or ‘Guy Maddin’, to name just a few first-person filmmakers. Through his narcissistic humour, Buba sabotaged his position of power as a way of remaining close to his neighbours, admitting one sin after another in a recurrent joke about his Catholic background: ‘

I started to feel guilty,’ he says right after his televisual incarnation states the opposite, because ‘

my success seemed dependent on the failure of others.’ Those ‘others’ are basically his own friends and actors: Jimmy Roy, Stephen Pellegrino, Natalka Voslakov, Ernie Spisak and especially Sal Caru, the local street hustler who starred in

Sweet Sal.

6 Lightning Over Braddock should have been another film about Sal, but apparently his unstable personality spoiled this possibility. In another example of the aesthetics of failure, the documentary focuses instead on the troubled relationship between Tony and Sal, who respectively embodied the friend who succeeds and the friend who fails to succeed, as well as the filmmaker and his star. In these sequences, it is never clear what was real and what was staged because their characters replace their real identities, leading the film towards the field of self-fiction.

Sal’s failure to become an actor is just one of the many personal stories that symbolise Braddock’s decline. According to Buba, the local entrepreneur Jimmy Roy also failed in business twelve times despite his blind faith in the American Dream: ‘

You are born to succeed,’ he states in a sequence of

J. Roy: New and Used Furniture, ‘

and if you don’t succeed it’s your own fault because you didn’t take control on what you think. What you think is gonna decide what you do, and what you do is gonna decide what you get.’ Such a speech somehow echoes business theories about self-confidence, but Roy’s failure in achieving his purpose turns him into a Don Quixote, the opposite myth from the self-made man. Buba, meanwhile, also fails in his project to make ‘

the film that will raise consciousness’ and becomes another Don Quixote: as the grant money was running out, his doubts about how to make the film apparently prevented him from finishing it, or at least from making it as he would have like.

7 For instance, he could not even show his old short films as they really were, as happened with Steve Pellegrino’s musical performance in

Mill Hunk Herald, a sequence in which Buba replaced the original soundtrack with an explanation about why he had to remove it:

In this part of the film, Steve Pellegrino plays ‘Jumping Jack Flash’ on the accordion … but you won’t get to hear him play. I called about acquiring the rights to the song, but they wanted $15,000 for it. I told them, ‘I don’t want Mick Jagger to come to Braddock to sing it. I have a friend who plays it on the accordion.’ They still wanted $15,000. $15,000 is three times the per capita income of a Braddock resident. I didn’t think it would be a politically correct move to pay that kind of money for a song. In fact, it’s crazy. This isn’t a Hollywood feature we’re making here. I know some of you are going to think this sounds real Catholic, but when I die and get to heaven, what if instead of St. Peter being at the gate, it’s Sacco and Vanzetti, and they say to me, ‘You paid $15,000 for a song instead of spending that money for political organizing?’ I wouldn’t get in. So talk to the person sitting next to you and try to remember how the song goes, and then sing along with Steve.

Paul Arthur considers that this aesthetics of failure is the film counterpart of all those stories about frustration and defeat embodied by Buba’s friends. The filmmaker, his project, his friends and his hometown are thereby bound in ‘a concordance of nonfulfillment’ that ultimately guarantees ‘authenticity and documentary truth’ (1993: 132). By means of a mise en abyme similar to that used by Federico Fellini in 8½ (1963), the account of the impossibility of making a film finally becomes that film, although the final reunion of the characters in Lightning Over Braddock is not a happy party but a campy sequence in which Jimmy Roy sings a theme song entitled ‘Braddock City of Magic’, the one that had already opened the film. Despite the intentional excess of Buba’s mise-en-scène and Roy’s performance – described as ‘Las Vegas nightclub-style’ by Pat Aufderheide (1989) – the sequence is a sincere wail for a dying place of memory that uses ironic detachment to express primary emotions. The song’s chorus leaves no doubt about Buba’s feelings: ‘Braddock … city of magic. Braddock … city of light. Braddock … where have you gone?’

This kind of staged sequence depicts the aforementioned tendency of Braddock residents to daydream. Throughout the film, Buba unleashes his fantasy and parodies Hollywood popular genres such as the musical, the gangster film or the action film. Thanks to his troupe of amateur actors, he shoots his own versions of the film icons of the time, reflecting on and also criticising ‘the seduction of mainstream cinema’ (Lane 2002: 139). Thus, along with the opening and closing sequence,

Lightning Over Braddock includes up to four fictional set pieces that freely combine genres and characters: a local staging of Gandhi’s assassination that rather resembles John F. Kennedy’s; an ‘ethnic detective story’ filled with Italian stereotypes and inspired by

The Godfather (Francis Ford Coppola, 1972); an action sequence in which Sal, characterised as Rambo, takes revenge on Buba’s snubs and shoots him to death, and a techno-pop musical composed by Steve Pellegrino and entitled ‘Death of the Iron Age Café’, in which the dancers are industrial workers whose choreography bears a reasonable likeness to the movements of the living dead, whether because it is a metaphor for industrial decline or perhaps because the dancers’ only previous acting experience was in a horror movie directed by George A. Romero, another Pittsburgh-based filmmaker.

All these daydreams are also part of the historical world, given that they documented the filmmaker’s mindscape, which is itself a reflection of his time and place. Officially, Buba mixed fiction and documentary because ‘I wanted the viewers to be in doubt about what was real and what wasn’t, instead of just sitting there and being a good consumer’ (in Aufderheide 1989), although that combination can also be interpreted as a cover letter to Hollywood, an ‘advertisement’ of the filmmaker’s skills, as Arthur has pointed out (1993: 132). Hollywood escapism is the exact reverse of what a social documentary should be, but the temptation of selling out to mainstream cinema is so strong that the filmmaker apparently surrendered to it: ‘

Father, I no longer want to make social documentaries,’ he says to a priest, in a parody of his own confession, ‘

I want to make a Hollywood musical!’

8 In this sense, the images of Buba visiting the Chinese Theatre in Los Angeles, where he pretends to leave his fingerprints on the pavement, serve as incriminating evidence of his sin as committed documentary maker. These grandiose delusions contrast with his everyday life in Braddock: like Sal, who summarised his days as ‘

wake up, walk around, same garbage’, part of Buba’s self-portrait consists of sequences in which he is alone at home watching television and wondering how to make his film. Like everyone else, he also wants ‘

money, power and fame’, the usual promises of the American Dream according to its Hollywood version. The acknowledgement of his self-centredness, however, frees him from guilt because it places him closer to people than to artists, counteracting any haughty pose. Consequently, by showing ‘the precarious link between individual and community in an America captivated by media images and fame’ (Aufderheide 1989), Buba actually constructs ‘an authentic individuality that also speaks for [his] community’ (Lane 2002: 143).

Lightning Over Braddock thereby challenges the authority of journalistic documentaries to depict what was going on in the Rust Belt. In fact, during a protest against a plant closing in Duquesne, Buba openly criticises their supposed objectivity by means of a staged interview with a television critic:

9

Margie Strosser (TV critic):

Finally, sophisticated media who know how to tell a story are getting involved. […] Local people … fail to see the big picture, and also contribute to misappropriations of political struggle.

Woman reporter: My father worked for the mills for forty years. You mean to tell me that someone from out of town can tell the story better than I could?

Margie Strosser: Yes, that’s precisely what I’m saying, because you can’t be objective. And your subjectivity may be poetic and well-intentioned but is probably provincial.

This interview was scripted from a conversation that Buba overhead at a cocktail party, and it raises the question of his own ability to depict the plight of his hometown (see Aufderheide 1989, Lane 2002: 143). Was he – or any other local filmmaker in whatever city – qualified to do so? The film clearly states that yes, he was. A decade before the outbreak of digital technology, Buba was already fulfilling Francis Ford Coppola’s prophecy about the future of filmmaking announced at the end of Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse (Fax Bahr, George Hickenlooper & Eleanor Coppola, 1991):

To me, the great hope is that now these little 8mm video recorders and stuff have come out, and some … just people who normally wouldn’t make movies are going to be making them. And you know, suddenly, one day some little fat girl in Ohio is going to be the new Mozart, you know, and make a beautiful film with her little father’s camera recorder. And for once, the so-called professionalism about movies will be destroyed, forever. And it will really become an art form. That’s my opinion.

In stark contrast with the professionalism of mainstream media, Tony Buba claims his right to be the accredited voice of Braddock after having documented its decline for the fifteen years that precede the making of this film. That activity allows him to show the changes in the cityscape through his own footage, comparing images framed from the same camera position in the 1970s and 1980s, the same device that William Raban had already used in Thames Film. Lightning Over Braddock thereby offers an insightful portrait of the post-industrial crisis that works on two levels: on the one hand, it is a digest of Buba’s guilty pleasures that summarises and expands his amateur film career; on the other, it ultimately becomes the social documentary that he strove so hard to make. In short, by combining an ironic self-portrait based on the aesthetics of failure with committed activism and guerrilla practices, both Tony Buba and Michael Moore widen the discursive possibilities of the socio-political documentary film, joining the defence of their respective communities with the expression of their own subjectivity.