Academic prose sometimes gives unexpected surprises to the reader, especially when its refined wording offers a glimpse of the writer’s humanity. In this regard, the most remarkable feature of America, Jean Baudrillard’s travelogue across the United States, is its shameless arrogance:

Where the others spend their time in libraries, I spend mine in the deserts and on the roads. Where they draw their material from the history of ideas, I draw mine from what is happening now, from the life of the streets, the beauty of nature. This country is naive, so you have to be naive. Everything here still bears the marks of a primitive society: technologies, the media, total simulation (bio-, socio-, stereo-, video-) are developing in a wild state, in their original state. Insignificance exists on a grand scale and the desert remains the primal scene, even in the big cities. Inordinate space, a simplicity of language and character. […] My hunting grounds are the deserts, the mountains, Los Angeles, the freeways, the Safeways, the ghost towns, or the downtowns, not lectures at the university. I know the deserts, their deserts, better than they do, since they turn their backs on their own space as the Greeks turned their backs on the sea, and I get to know more about the concrete, social life of America from the desert than I ever would from official or intellectual gatherings. (1988: 63)

Judging by these impressions, Baudrillard certainly had a good time on his American holidays. Such an exhibition of superiority does not seem the best way to understand a foreign country, but it must be recognised that Baudrillard managed quite well to synthesise the most obvious features of hyperreal America in a handful of aphorisms. Regarding urban experience, for example, he wrote one of the most quoted passages about the cinematic city:

The American city seems to have stepped right out of the movies. To grasp its secret, you should not, then, begin with the city and move inwards to the screen; you should begin with the screen and move outwards to the city. It is there that cinema does not assume an exceptional form, but simply invests the streets and the entire town with a mythical atmosphere. (1988: 56)

This idea has inspired almost as many researchers as city planners in the last twenty-five years. Nowadays, the model for reshaping urban space does not come from architectural theory anymore, but from film practice: the current political agenda is less concerned about the integral transformation of the built environment than about the aesthetic renewal of strategic locations. In fact, since the crisis of modernist approaches in urban planning, the city is no longer conceived as the sum of its parts, because it is much more profitable to break its unity and concentrate efforts and investments in isolated and limited spaces, downsizing the scope of action to the level of the film set. The city is thereby divided in increasingly smaller parts that gradually lose their connections to the point of becoming a scattered archipelago in which the old continuum is replaced by a sequential experience. This process seems to be especially advanced in Los Angeles due to its long tradition of urban ghettoisation, which operates at both ends of the socioeconomic ladder, but also to the gradual appropriation of the cityscape by the film industry. For better or worse, the local government has definitely assumed the historical identification between Los Angeles and Hollywood, causing a reversal in their usual relationship: for decades, the image of the city was created inside studio lots, but since the 1980s, according to Tony Fitzmaurice, several parts of the city have begun to consciously mimic ‘images from Hollywood’s past in the name of urban renewal … reshaping the physical fabric of the city itself into the simulation of a simulation’ (2001: 21).

This is not exactly a novelty, given that the architectural heritage of Los Angeles has always been characterised by its eclecticism. In the 1920s, Grauman’s Egyptian and Chinese Theaters were originally designed as fakes in which the ornamental elements of their façades did not correspond to their time and place. Half a century later, however, the same buildings reached the status of cultural monuments thanks to their condition as mythical venues for moviegoers and, above all, because they remained in place in a city with very few old buildings. In the 1960s, Kevin Lynch had already noticed that ‘the fluidity of the environment and the absence of physical elements which anchor to the past are exciting and disturbing’ (1960: 45), a perception that led him to diagnose a ‘widespread, almost pathological, attachment to anything that had survived the upheaval’ among the Angelinos (1960: 42). Grauman’s Egyptian and Chinese Theaters have benefited from these circumstances, insofar as they have passed from blatant simulations of exotic settings to authentic examples of the 1920s’ fantastic architectures.

Following this logic, the postmodern revival of this style – the simulation of a simulation – should also be ‘authentic’ as a product of our time, in which the excess of hyper-awareness and the systematic abuse of quotes, tributes, plagiarism, remixes and mash-ups threaten to exhaust our creativity. A typical product of this kind of urban planning is the Hollywood and Highland Center, which has been described by Josh Stenger as ‘a space wherein the gaze of the moviegoer, the shopper, and the tourist become interchangeable, where the spectacular overwhelms the mundane and where Hollywood-the-place can be rendered in stucco façades of Hollywood-the-cultural-myth’ (2001: 69–70). In spots like this, Los Angeles becomes a city-spectacle as influenced by Hollywood as by Disneyland, a fantasy restricted to a few blocks where ‘everything is tactile and visible, but it has been emptied of any deep meaning’, as Carlos García Vázquez has said (2004: 79; my translation). Consequently, urban space undergoes a process of theming in which the spatialities and temporalities characteristic of leisure complexes have created a distorted perception of the city.

Once this point is reached, Baudrillard’s theory about the precession of simulacra, based on the Borgesian metaphor of the map and the territory, finds its best expression: ‘the territory no longer precedes the map, nor does it survive it. It is nevertheless the map that precedes the territory – precession of simulacra – that engenders the territory’ (1994: 1). In Southern California, without going any further, the relation between the city and the territory is completely mediated by the cinematic, which would be the map that covers the territory, or rather the model that shapes what is supposed to be reality. Nevertheless, there have always been as many realities as observers, as the two films discussed below seem to suggest: first, The Decay of Fiction contrasts the material reality of the Ambassador Hotel ruins with the mental reality of its cinematic avatars; and then, Los Angeles Plays Itself looks for documentary revelations – that is, the real – in more than two hundred feature films – that is, the imaginary.

The Decay of Fiction: Ghosts of Film Noir

Pat O’Neill’s creative personality is split into two different facets. On the one hand, he is an avant-garde filmmaker interested in exploring the filmic surface of multiplanar images; on the other, he is also an expert technician specialising in optical printing.

1 His career combines the production of more than twenty experimental works with the management of a successful special effects company, Lookout Mountain Films, whose services have been required in mainstream films such as

Piranha (Joe Dante, 1978),

Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back (Irvin Kershner, 1980),

Star Wars Episode VI: Return of the Jedi (Richard Marquand, 1983),

Superman IV: The Quest for Peace (Sidney J. Furie, 1987) and

The Game (David Fincher, 1997). This blend of independent filmmaking and technical proficiency has earned him the nickname ‘two-faced’ (see De Bruyn 2004), although it is unclear who is Dr. Jekyll and who is Mr. Hyde: for decades, he has applied the findings of his experimental works to Hollywood features, using the income received from these jobs to finance new films and thus further his formal investigations.

David E. James has located O’Neill’s artistic roots in four different traditions: Expressionism, Surrealism, abstract animation and structural film (2005: 439). His work, as Paul Arthur argues, ‘operates in the gap between the hermetic and the demotic, between image-fragments whose significance remains obscure and iconography familiar enough be lodged in our cultural memorial banks’ (2004: 67). Accordingly, his tendency to play with the usual narratives and archetypes of popular genres is quite remarkable: ‘O’Neill’s early films,’ Arthur says, ‘display the strongest affinities for sci-fi, the next group leans toward the western, while his latest projects explore formal and cultural resonances attached to film noir’ (2004: 73). The western and film noir have shaped the imaginary of Los Angeles throughout the entire twentieth century, creating a cinematic city that is explicitly recalled in O’Neill’s three feature films: Water and Power (1989), Trouble in the Image (1996) and The Decay of Fiction (2002). All of them, as James has pointed out, simultaneously address ‘the medium of film, the history of the movies, and the geography in which the former became incarnate as the latter’, exploring both the image and the landscape in search of clues that explain their historical interdependence in Southern California (2005: 439).

Water and Power, O’Neill best-known work, represents the urban experience through a kaleidoscopic editing of disjointed images. The film deals with the negative effects that Los Angeles’s water policy has caused in the surrounding countryside, which has been exposed to accelerated desertification due to its systematic overexploitation for decades. Certain passages seem to have been inspired by the story of the Owens Valley – one of the main scenes of the California Water Wars in the 1910s and 1920s – but the narrative framework is so cryptic that it prevents any attempt at establishing a closed interpretation. Anyway, what is clear is that O’Neill reflects on the complementary nature of the California wilderness – the landscapes of the western – and the hidden places of the city – the usual setting of film noir. His way to visually match these spaces is to superimpose them in long dissolves that suggest their geological continuity, creating the impression that the city and the territory are actually embedded into one another. A similar effect is achieved thanks to the use of ‘a specially designed computerized motion-control device that permitted O’Neill’, as James has explained, ‘to make very exact tracking and panning shots and to duplicate those motions exactly’, thereby creating a visual palimpsest in which rural and urban landscapes are simultaneously shown through the same camera choreography (2005: 432). By means of these techniques,

Water and Power raises the issue of the confusion between the map and the territory, or between the city and its representations, reaching the point of reducing Los Angeles to a series of western and film noir commonplaces. For this reason, the excerpts of

The Docks of New York (Josef von Sternberg, 1928),

The Last Command (Josef von Sternberg, 1928),

The Lady Confesses (Sam Newfield, 1945) and

Detour included in the film do not only serve to set a noir atmosphere, but rather to locate the audience in the domain of the simulacra.

The Decay of Fiction shares some features with Water and Power, such as its sense of place, the use of superimposed images and the abundance of film references. Its main novelties, however, are the spatial unity of the plot and the decision to organise most sequences around a few narrative strands. The setting of the film, the old Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, is its main subject and character, basically due to its nature as place of memory at a time in which it had already lost its functionality. In the following quote, Marsha Kinder offers a good summary of the accumulation of significant events that took place in the hotel during the seven decades that it was open, from 1921 to 1989:

Built in 1920 on LA’s ‘Wilshire Corridor’, the hotel helped redirect the city’s urban sprawl from east to west, from downtown to the sea. Its glamorous Coconut Grove nightclub was the place where downtown power brokers first mingled with Hollywood stars, where Joan Crawford was discovered in a dance contest and Marilyn Monroe in a bathing-suit competition, and where many celebrities won their Oscar and Golden Globes. The hotel had permanent residents, like newscaster Walter Winchell, while others, like FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover visited every year. The hotel is now remembered primarily as the place where Robert Kennedy was assassinated while campaigning for the Democratic presidential nomination – a traumatic event that transformed the hotel’s cultural capital and changed the course of American history. (2003: 356)

Paul Arthur has compared the hotel with ‘the desert’s urban double’, because it is ‘an oasis for the gathering of mythic as well as social significance’ (2004: 75). Each guest has left there a tiny part of him or herself, contributing to both the physical erosion of the place and its preservation in the social imaginary. Hollywood, in turn, has used the Ambassador Hotel as location for many features, television programmes and music videos, such as

The Graduate (Mike Nichols, 1967),

Pretty Woman (Garry Marshall, 1990),

True Romance (Tony Scott, 1993),

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (Terry Gilliam, 1998),

Catch Me If You Can (Steven Spielberg, 2002) and

Bobby (Emilio Estevez, 2006), to name but a few. These titles have already documented the place – both the real and imaginary place, as Edward Soja would say – but

The Decay of Fiction seeks to go further: this time, O’Neill looks for the

genius loci of the hotel in both its physical ruins and the echoes of the narratives that took place there.

The first shot of the film is a time-lapse image of an empty and derelict room: the paint has flaked off, the windows are broken and the wind slowly moves the curtains. In a few seconds, the light changes from dawn to dusk, establishing the guiding metaphor for the film: the decline of the Ambassador Hotel is preferentially depicted at twilight, because that hour symbolises a liminal state between day and night, decay and dematerialisation, presence and absence, existence and non-existence. That is the time in which ‘the ghosts of long-departed guests’, as James has called them, can return to the hotel, which become the ‘crime scene’ for some and a place of memory for most (2005: 436). This memorial dimension has been highlighted by the filmmaker himself in his statements about the film:

The film takes place in a building about to be destroyed, whose walls contain (by dint of association) a huge burden of memory: cultural and personal, conscious and unconscious. To make the film was to trap a few of its characters and some of their dialogue, casting them together within the confines of the site. The structure and its stories are decaying together, and each seems to be a metaphor for the other. (O’Neill in Rosenbaum 2003b)

Image 9.1: The Decay of Fiction, the translucent guests of the Ambassador Hotel

By means of his optical printer, O’Neill explores the formal possibilities of the visual palimpsest to bring life back to the building: first, he documented the appearance of its ruins at the turn of the century, filming them in colour, and then on these spaces he superimposed black-and-white images of a series of translucent figures that seem to have been endlessly repeating the same kind of dialogues and situations for half a century (

Image 9.1). These characters, played by contemporary actors, represent the former inhabitants of the place, who come to life thanks to fictional stories that imitate the film noir narratives of the mid-to-late 1940s and early 1950s. The film, however, does not develop a linear plot, but several unfinished micro-narratives that form a collage of film references. In principle, everything seems familiar to the audience in spite of its artificial nature, although most sequences do not refer to any particular title, except for those that visually or aurally refer to

Detour,

Possessed (Curtis Bernhardt, 1947),

His Kind of Woman (John Farrow, 1951),

Sudden Fear (David Miller, 1952) or

The Big Combo (Joseph H. Lewis, 1955), among other noirs. The main source materials for

The Decay of Fiction are then snatches of ‘half-remembered’ and ‘half-imagined’ films, as James has described them (2005: 436), a particular mindscape evoked from the very title, as the filmmaker has revealed:

I scribbled the words ‘The Decay of Fiction’ on the back of a notebook almost 40 years ago, tore it off and framed it 15 years later, and have wanted ever since to make a film to fit its ready-made description. To me it refers to the common condition of stories partly remembered, films partly seen, texts at the margins of memory, disappearing like a book left outside on the ground to decompose back into the earth. (O’Neill in Rosenbaum 2003b)

Inside this mindscape, the characters are always in trouble: both guests and staff are involved one way or another in suspicious activities, from coercion and betrayal to arguments and, who knows, perhaps murders. All of them are imbued with an aura of mystery and secrecy, and some have ‘names, backstories, tangled relationships [and] even individual nightmares’, as Arthur has noted (2004: 75). The dramatis personae includes the manager of the hotel, Jack, who seems to be the main character; a few guests who have their own narratives, like a couple of honeymooners or an elderly woman who lives in the hotel under the care of a nurse; the maids, waitresses, cooks, bellboys and the rest of the staff, who often serve as witness-narrators; the entertainers, torch singers and other performers of the Coconut Grove nightclub; some people who run their business in the hotel, such as a psychoanalyst or several prostitutes; and finally, as it could not be otherwise, the main couple of film noir, the crooks and the cops. These archetypes repeat situations seen a thousand times in classical films: a chase along a corridor, the search of a membership list, the removal of a body found in a room, etc. They embody the film imaginary associated with the place, an idea that had already appeared in other urban documentaries, such as A Cidade de Cassiano (Cassiano’s City, Edgar Pêra, 1991) or Shotgun Freeway: Drives Through Lost L.A (Morgan Neville & Harry Pallenberg, 1995).

The first of these two films is a short documentary made for an exhibition about Cassiano Branco, Portugal’s best-known modernist architect. Since one of his main works was a movie theatre, the Eden Cinema in Lisbon, experimental filmmaker Edgar Pêra decided to depict it in a staged sequence in which a man chases another from its art-deco lobby to its rooftop, thereby linking the building with its original purpose: to give life to all kinds of cinematic fantasies. Later on, the same idea was used by Morgan Neville and Harry Pallenberg in

Shotgun Freeway, a talking-heads documentary about Los Angeles. Most of the film consists of on-location interviews with local personalities: for instance, Mike Davis speaks from the concrete channel of the Los Angeles River, Buck Henry in front of a dressing room mirror, and James Ellroy while pretending to burgle a house at night. Nevertheless, there is a leitmotif that fills the editing gaps: the presence of two fictional characters, a private eye and a

femme fatale dressed in the fashion of the 1940s, who appear in different places of the city throughout the documentary. The private eye spends most of the footage taking pictures of certain places in which he later sees their current appearance, as if in a flash-forward, and the

femme fatale behaves like a ghost that symbolises the spirit of the city. The ethnic dimension of the cast’s choice (the man is played by an Anglo-Saxon actor, while the woman is embodied by a Latina actress) places these archetypes within Southern California history, according to which Anglo-Saxon settlers inherited Latino landlords’ properties by marrying their daughters (see Davis 1990: 106–7). In this case, film references introduce a subtle reflection on the history of the territory, because they mirror the racial evolution of its population.

The metafilmic dimension of The Decay of Fiction also pervades the soundtrack, in which the voices of certain film noir stars (Kirk Douglas, Robert Mitchum, Joan Crawford, Dana Andrews, etc.) can be heard as if they were an EVP. Indeed, many invisible actions are represented through soundscapes that seem echoes of the past: the bell of the elevators, the sound of running water, a few telephone conversations in empty rooms, guffaws, shouts, passing cars… Even Bobby Kennedy’s assassination is recalled through a radio broadcast while images show the empty Embassy Room, the place where he gave his last speech after winning the California Democratic primary election; this time, the translucent extras will only appear after the tragedy, playing the onlookers who saw how the politician’s wounded body was evacuated on a stretcher.

Most sounds, as Jonathan Rosenbaum has pointed out, are ‘pitched at the periphery of normal perception, so that even when they connote dramatic or violent action, they seem to be on the verge of evaporating’ (2003b). The resulting effect contributes to the impression that the Ambassador Hotel is haunted by ghosts who are doomed to repeat familiar dialogues. To give an example, here is a transcription of the last conversation in the film, in which a couple splits up:

Woman (talking on the phone): Hi, I’m checking out the room 1104. Yes. I’ll be done in ten minutes.

Man (entering the frame): Hey, hey, what’s this?

Woman (to the man): What it looks like … I have to go.

Man (trying to embrace her): Come on, can we talk?

Woman (angry): I think we’ve done enough talking and you have not said anything yet.

Man (trying to kiss her): But … I love you!

Woman (sad): Are you joking?

Man (offended): Yeah, yeah … it’s joke, just words.

Woman (laconic): That’s what I thought. Just words…

This kind of dialogue helps to create a particular tone and mood that condition the audience’s perception of the place: after having inspired many film locations, the Ambassador Hotel finally became a real film location where everything echoes past events. In this sense, The Decay of Fiction follows the trail of two previous works that reflected on the issue of the eternal return: the short novel La Invención de Morel (Adolfo Bioy Casares, 1940) and the film L’année dernière à Marienbad (Last Year at Marienbad, Alain Resnais, 1961). In Bioy Casares’s book, the narrator falls in love with a woman who is actually a spectre produced by a mysterious device, the same as other people that he meets on the island where he lives. All of them had been recorded long time ago by the invention that names the novel, which might be a futuristic form of holographic cinema. Last Year at Marienbad, in turn, presents a series of characters apparently trapped in a luxury hotel where a man approaches a woman and keeps trying to convince her that they have already met, something that is never clear if it really happened. Resnais and his screenwriter, Alain Robbe-Grillet, systematically explore all the possible developments of that situation to the point that the man’s story becomes a premonition of what will finally happen, as well as a memory of what might have already happened.

Both

La Invención de Morel and

Last Year at Marienbad, as well as

The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980) and obviously

The Decay of Fiction, are based on the idea of the endless repetition of previous events within a closed space, where the time of the story has first stopped and then prolonged until a present that is actually a variation of the past. In these places, according to Arthur, ‘history has collapsed, time is definitely out of joint, and we can no longer parse substance from illusion’ (2004: 74). Consequently, the Ambassador Hotel is depicted as ‘a place of both narrative and analytic possibility’, the main virtue that Charlotte Brunsdon attributes to cinematic empty spaces such as ‘bombsites, demolition and building sites, parks, temporary car-parks, derelict warehouses and docks’:

These spaces are often the site of what we might call a ‘hesitation’ in the cinematic image, when it can be read either within the fictional world of the narrative, or as part of extra-filmic narratives about the history of the material city, or, more formally as a self-reflexive moment of urban landscape. (2010: 91)

In The Decay of Fiction the Ambassador Hotel admits these three levels of reading: regarding the first, it is the fictional setting of different individual stories that take advantage of what Kinder describes as ‘the meta-narrative function of the inn as stopping place in picaresque fiction’ (2003: 357); furthermore, it also plays itself as a vestige of another era, which coincides with what Gilles Lipovetsky and Jean Serroy call ‘classical modernity’ (2009: 17); and finally its ruins at the turn of the century work as a spatio-temporal landmark of the evolution of Los Angeles’s cityscape. In this last sense, the abandoned building chronicles several stages in local history: its heyday, when Wilshire Boulevard provided a common ground for the meeting of Downtown, Hollywood and Westside residents; its decline, when the urban crisis of the 1970s and 1980s hit the city and especially this area; and its renewal, when the neighbourhood became ‘the booming Koreatown’, an expression coined by Korean American sociologist Eui-Young Yu (1992) after the 1992 riots, although that transformation arrived too late for the Ambassador Hotel.

Dirk De Bruyn has also interpreted the building as ‘a metaphor for the camera itself (a monolithic camera obscura which O’Neill intermittently occupied and explored during the six years of the film’s stop/start making)’ (2004). This approach suggests that it is the hotel that ultimately creates its ghost and narratives, even when they are beyond real referents: for instance, the naked spectres who take part in an orgy towards the end of the film actually come from the filmmaker’s unconscious, as James has noted (2005: 436), but even so they are summoned by the

genius loci of the place. The way O’Neill understands the creative process opens the door to the expression of his own subjectivity: ‘I like to work within the gaps between reality and story, to look at what is going on around the story, its context, and to make that a part of my conversation with the audience’ (in Rosenbaum 2003b). The presence of ‘my’ in this statement reveals the perspective from which

The Decay of Fiction was conceived: the film is a personal interpretation of the cultural significance of the Ambassador Hotel that uses film noir archetypes as references suggested by the place itself in order to establish a playful dialogue with the audience. This subjective dimension is reinforced by the inclusion in the footage of an imperceptible self-portrait of the filmmaker: ‘in the middle of the film’, James explains, ‘we find him, sitting in one of these empty salons, typing, until his attention is drawn away by a ghostly woman’ (2005: 438). Arthur has said that O’Neill usually appears in his films as a way of playing with the anonymity of avant-garde filmmakers (2004: 68), but this self-portrait in particular is also a voluntary inscription within the fictional world: the filmmaker depicts himself as a demiurge who has been haunted by the place, its ghosts and its ‘huge burden of memory’ (O’Neill in Rosenbaum 2003b).

In conclusion, The Decay of Fiction uses film references as mediums to return to the Ambassador Hotel’s heyday just before its dematerialisation, thereby addressing both its past and present. This device brings to the foreground two related issues: the way ‘old movies continue to circulate in consciousness’ (Arthur 2004: 75), and the way they shape our current perception of urban space. Nowadays, that building is a missing landmark in Los Angeles – it was demolished between September 2005 and January 2006 – but it still stands in the local imaginary thanks to its film appearances. O’Neill’s time-lapse shots captured the erosion of time on its ruins, sometimes establishing a visual contrast between its architecture and the downtown skyscrapers, which represent a city to which the hotel no longer belongs. Therefore, all those who want to visit this anachronistic place again will have to look for it in film heritage.

Los Angeles Plays Itself: A Critical Tour Through Cinematic LA

Thom Andersen belongs to the same generation and film milieu as James Benning and Pat O’Neill: they were born around 1940, became experimental filmmakers under the influence of structural film, and have taught at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) in recent decades.

2 Over the years, their prime interest has shifted from formal concerns to social issues, although Andersen’s works have always kept a ‘metafilmic self-consciousness associated with structural film’ (James 2005: 420). According to Daniel Ribas, most of his films are explicitly focused on ‘the way cinema alters our perception of reality’ (2012: 89), especially three of his four features:

Eadweard Muybridge, Zoopraxographer (1974),

Red Hollywood (Thom Andersen & Noël Burch, 1996) and

Los Angeles Plays Itself. After the last of these, Andersen’s growing interest in urban space has led him to film his own city symphony, the short

Get Out of the Car (2010), and a documentary on the work of Portuguese architect Eduardo Souto de Moura,

Reconverção (

Reconversion, 2012), made the year after he was awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize. All these films combine a historical approach with a subjective sense of place, which ultimately locates Andersen’s spatial and metafilmic reflections within the tradition of the essay film.

The analytical device of Los Angeles Plays Itself was previously tested in Red Hollywood, a work that was already composed of film quotes: it consists of a few interviews with some blacklisted screenwriters, such as Paul Jarrico, Ring Lardner Jr. and Abraham Polonsky, and hundreds of excerpts from fifty-three Hollywood features made by Communist militants and sympathisers in the 1930s and 1940s. Both this documentary and its published version, Les Communistes de Hollywood: Autre chose que des martyrs (Thom Andersen & Noël Burch, 1994), are guided by a didactic impulse that seeks to restore the blacklisted people’s place in film history, but its commentary also draws attention to progressive topics that later disappeared from mainstream cinema, such as solidarity among workers, support for the underprivileged or the claim of gender equality.

Unfortunately, Andersen and Burch did not own the rights of the films that they quoted, so they had to make

Red Hollywood as a private videotape and then distribute it clandestinely. For this reason, this work, like

Los Angeles Plays Itself, still lacks an official edition that can be legally acquired: they are, and will probably be for many years, bootleg films because the studios are not willing to lend their films for a nominal fee.

3 Accordingly, the images included in these two works actually come from Andersen’s personal videotape collection, from which he usually takes short clips to show in his film classes:

The teaching in small classes that I do in graduate seminars is based on lectures with movie clips. I’ve been working that way for a long time, since VHS started, but certainly, at least since I started at CalArts in 1989/90. [Los Angeles Plays Itself] began as a similar project. A talk – not for the school, but for the public – with movie clips that could be presented. […] It’s a lot of work to cue in all the movies on VHS and prepare all the clips, so I thought of making just a little movie, so it would all be there. Whenever somebody was interested I could offer it to them. But it changed. It transcended those beginnings. It turned into something a little more than an illustrated lecture, although I’m sure there are those who regard it as such. (Andersen in Ribas 2012: 92)

The main idea of

Los Angeles Plays Itself is to read feature films as indirect and unpremeditated documents of their time: ‘

If we can appreciate documentaries for their dramatic qualities,’ the narrator says in the prologue, ‘

perhaps we can appreciate fiction films for their documentary revelations.’ From this initial statement, Andersen claims the memorial value of those titles that preserve the real image of missing places, inasmuch as ‘

images of things that aren’t there any more mean a lot to those of us who live in Los Angeles’. Moreover, he highlights the significance of film locations themselves by arguing that ‘

in a city where only a few buildings are more than a hundred years old, where most traces of the city’s history have been effaced, a place can become a historic landmark because it was once a movie location’. The accuracy with which he locates old images in the cityscape is comparable to the geographical precision of Leon Smith’s and John Bengston’s guides of film locations (see Smith 1988, 1993; Bengston 1999, 2006, 2011). Nevertheless,

Los Angeles Plays Itself is much more than a plain description of the way Hollywood has depicted the main landmarks of the city. Beyond this approach, Andersen attempts to link the setting of a film to its meaning in order to expose the power discourses that lie behind many titles, an idea that was later developed by Alain Silver and James Ursini in their book

L.A. Noir: The City as a Character (2005). Consequently, as Michael Chanan has pointed out, ‘Andersen shifts the way we look at these images, defamiliarising them by deconstructing the language of screen space which produced them’ (2007: 77)

After five years of work, Andersen ‘published’ the results of his research in a film instead of a book, although he later curated a retrospective on the same issue for the Austrian Film Museum and the Vienna International Film Festival (see Andersen 2008). Despite the logical similarities in terms of content between the film’s commentary and the introduction to the retrospective’s catalogue, both texts differ in style and, above all, in their way of creating meaning: the introduction is much more academic and digressive, because it is a text to be read; while the commentary is based on a continuous dialogue with images that goes beyond the format of an illustrated lecture. Thus, Andersen sometimes introduces certain sequences, but most times the quoted films directly answer his words or vice versa, as in a screwball comedy. Indeed, in many passages of Los Angeles Plays Itself, there is more information in the images than in the commentary: a single shot can contain the title of the quoted film, the presence of a famous performer, the mood and iconography associated with a given time and genre, some detail that allows the audience to identify the film location, and a fictional action that provides the setting with a certain meaning. Taking this polysemy into account, the discourse of the film is produced by both the commentary and the selection and editing of images. In this regard, it is significant that Andersen did not sign his work by means of the usual expression ‘directed by’. Instead, he chose to write in the opening credits ‘text, research and production by Thom Andersen’, thereby emphasising the differences between these three activities.

The working hypothesis of the film assumes that there may be more or less truthful representations, but most are actually misrepresentations, as implied by the last sentence of the prologue: ‘

We might wonder if the movies have ever really depicted Los Angeles.’ And what about

Los Angeles Plays Itself? Are its metafilmic strategies a truthful representation? In principle, its fragmented nature has something in common with the city: it is a film made of pieces that attempts to depict a city made of pieces. Zapping from one film to another seems, therefore, an appropriate technique to convey the multiple and disjointed experience of a place where Thai Town is just north of Little Armenia. One of the chapters of Soja’s book

Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory is precisely entitled ‘It All Comes Together in Los Angeles’, because there the real city is able to mimic anywhere in the world, just like the cinematic city:

One can find in Los Angeles not only the high technology industrial complexes of Silicon Valley and the erratic sunbelt economy of Houston, but also the far-reaching industrial decline and bankrupt urban neighbourhoods of rust-belted Detroit or Cleveland. There is a Boston in Los Angeles, a Lower Manhattan and a South Bronx, a São Paulo and a Singapore. There may be no other comparable urban region which presents so vividly such a composite assemblage and articulation of urban restructuring processes. Los Angeles seems to be conjugating the recent history of capitalist urbanization in virtually all its inflectional forms. (1989: 193)

Andersen certainly feels at home in this urban chaos: both Los Angeles (his hometown) and the movies (his job) are his natural element, his place in the world. Hence the double reading of

Los Angeles Plays Itself: on the one hand, it is a film mapping of LA; and on the other hand, it is also a personal mapping of meaningful films and places. This double coding is established from the very beginning of the commentary: ‘

This is the city: Los Angeles, California. They make movies here. I live here. Sometimes I think that gives me the right to criticize the ways movies depict my city. I know it’s not easy. The city is big. The image is small.’ The use of the first-person commentary will continue throughout the entire film, blending objective information and subjective opinions without privileging one element over another. The outcome, as already happened in many other case studies in this book, is a film portrait of a lived city, although this time it is not a direct record of the filmmaker’s urban experience, but a compilation of his film experience of the city, that is, a mediated experience. The difference between Andersen and most viewers lies in his gaze toward urban space: while most of us have a foreign gaze toward Los Angeles – especially those who have ever been there – Andersen in turn has a native gaze, which allows him to recognise many film locations and link them to his memories of these places. This is the reason why he especially appreciates those films in which ‘

what we see is what was really there’, as he says regarding

Kiss Me Deadly (Robert Aldrich, 1955).

Contrary to what may seem, the narrator is not Andersen, but his friend and fellow filmmaker Encke King. Why did Andersen not use his own voice to read such a subjective text? For once, the reason has no serious ontological implications:

Encke King is an old friend of mine. He was a student at CalArts a long time ago, when I was first teaching there. I’ve always liked his voice. He knows me pretty well. I thought he could do a good job of playing me. I don’t like hearing the sound of my own voice. A lot of people are like that, maybe most. Especially when you’re editing narration and have to listen to someone talk constantly. It would have been a drag to edit my own voice. (Andersen in Erickson 2004)

Despite the fact that King is identified as narrator in the opening credits, only those who personally know Andersen can notice this splitting in the voice of the documentary: we hear Andersen’s words, but we do not hear him. Accordingly, Los Angeles Plays Itself can be regarded as a case of explicit presence of the author, because the filmmaker directly intervenes in the plot, although he does so by means of a stand-in. This option does not alter the subjective component of the commentary, and it even improves its metafilmic connections: King’s diction, as well as Andersen’s literary style, recalls the tone of hard-boiled fiction and film noir in a prime example of how documentaries internalise certain tropes of fiction. In fact, the way the commentary interrogates the images has been compared by David E. James with the hard-bitten attitude of private eyes such as Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, Mike Hammer or Lew Archer (2005: 421).

Like most detective stories, Los Angeles Plays Itself strives to bring to light what is beneath the surface, which in this case is an elusive city: ‘Los Angeles may be the most photographed city in the world, but it’s one of the least photogenic,’ Andersen (actually King) says. ‘It’s not Paris or New York. In New York, everything is sharp and in-focus, as if seen through a wide-angle lens. In smoggy cities like Los Angeles, everything dissolves into the distance, and even stuff that’s close-up seems far off.’ This description puts LA within the category of what Ackbar Abbas calls ‘the exorbitant city’, which is ‘neither securely graspable nor fully representable’ (2003: 145). Faced with the inability of cinema to depict his hometown, Andersen suggests some causes that lead his analysis toward the field of urban planning and local history:

Los Angeles is hard to get right, maybe because traditional public space has been largely occupied by the quasi-private space of moving vehicles. It’s elusive, just beyond the reach of an image. It’s not a city that spread outward from a centre as motorised transportation supplanted walking, but a series of villages that grew together, linked from the beginning by railways and then motor roads. The villages became neighbourhoods and their boundaries blurred, but they remain separate provinces, joined together primarily by mutual hostility and a mutual disdain for the city’s historic centre.

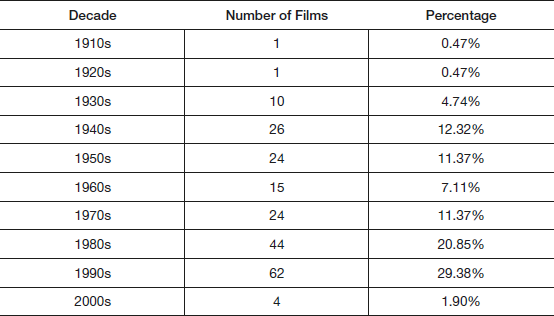

In order to overcome these limitations, Los Angeles Plays Itself quotes up to 210 different films, as well as a TV series, Dragnet (Jack Webb, 1951–59 and 1967– 70). Depending on the needs of the argument, the quotes can either be single shots or complete sequences: sometimes, the development of an idea may require a dozen quotes, while other times it needs longer excerpts. These are not the only visual materials of the film, of course: there are also a hundred original shots, two dozens of newspaper clippings, eight old pictures of missing places, a few shots of non-fiction footage taken from television, newsreels and other documentaries, and even an excerpt from Ricky Martin’s music video Vuelve (Wayne Isham, 1998). Perhaps some statistics, such as the distribution of films by decade and genre, may be useful to understand what kind of cinematic city is depicted in Los Angeles Plays Itself.

Table 9.1: Film Quotes by Decades

Source: My Own Elaboration

Table 9.2: Film Quotes by Genre

Source: My Own Elaboration

Half of the quotes come from films made in the twenty-five years prior to the release of Los Angeles Plays Itself. This overrepresentation of the 1980s and 1990s is firstly due to the temporal proximity of these decades: postmodern films were easier to find in VHS at the beginning of the 2000s than silent, classical or modern titles, and they were also more recognisable for contemporary audiences. Furthermore, this preference for recent features also reflects the tendency of postmodern cinema to appropriate previous references, ideas and film locations as if they had never been filmed before. Regarding the other periods, classical film is mainly represented by film noirs, and modern film by both local neorealism and titles by foreign filmmakers in Los Angeles. Only silent film is almost completely absent, partly because these films were mostly made inside the studios.

There are some genres that are more represented than others, of course, although many are interrelated. The two main blocks correspond, firstly, to thrillers, crime film and film noir, and secondly, to action, science fiction, disaster and horror movies. Dramas and comedies are well represented, unlike the musical, whose presence is purely anecdotal. Finally, other genres are included simply as oddities, such as gay porn cinema, avant-garde film or even documentary film. In this selection, the dominant genres broadly coincide with the five concepts developed by Erwan Higuinen and Olivier Joyard in the encyclopaedia

La ville au cinéma’s entry about Los Angeles: they speak about ‘

ville noire’, ‘

ville studio’, ‘

ville d’exil’, ‘

ville d’action’ and ‘

ville sans centre’, terms that may be translated, respectively, as ‘noir city’, ‘studio city’, ‘city of exile’, ‘city of action’ and ‘city without a centre’ (2005: 449–57). Obviously, the noir city comes from film noir, the studio city from the films about the making of other films, the city of exile from the titles directed by foreign filmmakers in Los Angeles, the city of action from postmodern thrillers and action movies, and the city without a centre from the multi-protagonist films of the 1990s and 2000s.

Not all significant works of these genres are included in

Los Angeles Plays Itself: a few notable absences are, for instance,

Singin’ in the Rain (Stanley Donen & Gene Kelly, 1952),

Beverly Hills Cop (Martin Brest, 1984),

Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994),

Magnolia (Paul Thomas Anderson, 1999) and

Mulholland Dr. (David Lynch, 2001). The reasons for these oversights are multiple: Andersen decided not to include any film about the entertainment industry unless he could approach it from another perspective; he did not always find something new to say about certain titles; or simply he was not always inspired, as he himself has admitted (in Erickson 2004).

4 Considering these limitations,

Los Angeles Plays Itself might include many more quotes, but then it would be redundant or lose its punch. The only films that Andersen has openly regretted not having had the opportunity to quote are some recent documentaries that grant visibility to people who seldom appear in Hollywood features, such as

Hoover Street Revival (Sophie Fiennes, 2002),

Bastards of the Party (Cle Shaheed Sloan, 2005),

Leimert Park: The Story of a Village in South Central Los Angeles (Jeannette Lindsay, 2006),

South Main (Kelly Parker, 2008) and

The Garden (Scott Hamilton Kennedy, 2008), which he considers ‘the best films about Los Angeles in the past ten years’ (2008: 22).

The most frequently quoted title is To Live and Die in L.A. (William Friedkin, 1985), which appears up to seven times, but Andersen does not go into detail about it: he just uses it as example of something else, not as one of the works that explain the city. The films that receive most ‘screen share’ would rather be Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944), Rebel Without a Cause (Nicholas Ray, 1955), Kiss Me Deadly, The Exiles (Kent MacKenzie, 1961), Chinatown (Roman Polanski, 1974), Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (Robert Zemekis, 1988), L.A. Confidential (Curtis Hanson, 1997) and the TV series Dragnet. Their analyses are located in the second and third part of the film, once the commentary has replaced its initial architectural approach with a more sociological one.

Los Angeles Plays Itself is divided into a prologue and three chapters, which are respectively entitled ‘the city as background’, ‘the city as character’ and ‘the city as subject’. The first presents Los Angeles as a scattered collection of film locations that not always represent the real city, but ‘

the city with no name’, a stand-in for anywhere in the world. The second explains how that nameless city became Los Angeles thanks to certain noirs that developed an accurate sense of place, such as

Double Indemnity or

Kiss Me Deadly. Finally, the third is devoted to works that explore local history in search of those unfortunate events that spoiled the Southern California dream, from the construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct that deprived the Owens Valley of its water resources (the back-story in

Chinatown) to the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) corruption and paranoid style in the 1950s, which was unintentionally revealed by

Dragnet and later reenacted in

L.A. Confidential. These intersections between local history and fictional plots express a nostalgia for ‘

what might have been’ that Andersen describes as ‘

crocodile tears’, because these stories replace the public history of the city with a secret one. This three-act structure leads Andersen’s discourse from the particular to the general, from the urban surface to the city’s unconscious and, above all, from the ‘representations of space’ to the ‘representational spaces’, to use Henri Lefebvre’s terms (1991: 33, 38–9).

In Los Angeles, as Andersen argues in the first chapter, the making of a film leaves traces in both its urban layout and the memory of its residents: ‘

plaques and signs mark the sites of former movie studios’, ‘

streets and parks are named for movie stars’, and even ‘

some buildings that look functional are permanent movie sets’. Through this dynamic, certain places have become civic monuments after having appeared in a successful film, which may provide them a fleeting fame and even ensure their preservation. Andersen uses visual enumerations to review the film career of well-known landmarks that not always play themselves, such as the Bradbury Building, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis House or Union Station, as well as those that do so, from the City Hall or the Griffith Planetarium to the fourlevel freeway interchange or the Hollywood Sign. The full list also includes ordinary spaces like ‘

Circus Liquor at Burbank and Vineland’ or ‘

Pink’s Hot Dogs at La Brea and Melrose’, which Andersen consciously puts on the same level as glamorous landmarks. The film is pervaded by this kind of joke, which actually challenge the most annoying and malignant lies of mainstream film: according to Andersen, ‘

to someone who knows Los Angeles only from movies,

it might appear that everyone who has a job lives in the hills or at the beach. The dismal flatland between is the province of the lumpen proletariat.’ That is to say that Hollywood has systematically favoured the two urban ecologies that have historically been identified with the way of life of the most affluent residents of the city: ‘Surfurbia’ and the ‘Foothills’, as Reyner Banham named them in the early 1970s (2009: 19–37, 77–91). On the contrary, the space inhabited by the majority of the population, the ‘Plains of Id’, is only visible as a bland and uniform backdrop in the carscapes filmed from Banham’s four ecology: ‘Autopia’ (2009: 143–59, 195– 204). Andersen accuses these commonplaces of cheapening the real city, giving as examples Hollywood’s inability to talk about an environment other than its own, or its tendency to denigrate the local heritage of modernist residential architecture ‘

by casting many of these houses as the residences of movie villains’.

Glamorous landmarks are what Lefebvre described as ‘representations of space’, but their images can give rise to ‘representational spaces’, especially when they have disappeared from the urban surface. In these cases, Andersen claims the memorial value of those films that recorded missing places at the time in which they still stood, because they allow the audience to return there, if only in fiction. Moreover, Los Angeles Plays Itself also shows the evolution of everyday spaces that have to be constantly rebuilt in order to adapt to changing patterns of consumption: ‘The image of an obsolete gas station or grocery store,’ Andersen says, ‘can evoke the same kind of nostalgia we feel for any commodity whose day has passed.’ Again, the filmmaker matches high and low culture, represented here by architectural heritage and ephemeral buildings, inasmuch as he considers that their differences dissolve once they have been incorporated into popular memory.

Images 9.2 & 9.3: Bunker Hill in Kiss Me Deadly (top) and The Exiles (bottom)

One of the most poignant passages of

Los Angeles Plays Itself is the sequence devoted to Bunker Hill, in which the history of the neighbourhood is re-enacted through less than a dozen titles:

The Unfaithful (Vincent Sherman, 1947),

Criss Cross (Robert Siodmak, 1949),

Shockproof (Douglas Sirk, 1949),

The Glenn Miller Story (Anthony Mann, 1954),

Kiss Me Deadly,

Indestructible Man (Jack Pollexfen, 1956),

Bunker Hill 1956 (Kent MacKenzie, 1956),

The Exiles,

The Omega Man (Boris Sagal, 1971),

Night of the Comet (Thom Eberhardt, 1984) and

Virtuosity (Brett Leonard, 1995) (Images 9.2 & 9.3). From these films, Andersen summarises its process of decline and subsequent renewal in four stages: the starting point is the late 1940s, when Bunker Hill represented ‘

a solid working-class neighborhood, a place where a guy could take his girl home to meet his mother’; then, by the mid-1950s, it became ‘

a neighborhood of rooming houses where a man who knows too much might hole up or hide out’. Later, between the 1960s and 1970s, its physical destruction was documented by the post-apocalyptic dystopia

The Omega Man; and finally, from the 1980s, its rebirth as a financial and arts district looks like ‘

a simulated city’ where nothing is real. This narrative largely coincides with Mike Davis’s account of the same process, which was precisely written during the making of

Los Angeles Plays Itself:

According to the 1940 Census, [Bunker Hill’s] population increased almost twenty percent during the Depression as it provided the cheapest housing for downtown’s casual workforce as well as for pensioners, disabled war veterans, Mexican and Filipino immigrants, and men whose identities were best kept in shadow. Its nearly two thousand dwellings ranged from oil prospectors’ shacks and turn-of-the-century tourist hotels to the decayed but still magnificent Queen Anne and Westlake mansions of the city’s circa-1880 elites. Successive Works Progress Administration and city housing commission reports chronicled its dilapidation (sixty percent of structures were considered ‘dangerous’), arrest rates (eight times the city average), health problems (tuberculosis and syphilis), and drug culture (the epicenter of marijuana and cocaine use). Yet grim social statistics failed to capture the district’s favela-like community spirit, its multiracial tolerance, or its closed-mouth unity against the police. […] A few years after the release of Kiss Me Deadly, the wrecking balls and bulldozers began to systematically destroy the homes of ten thousand Bunker Hill residents. […] A few Victorian landmarks, like Angel’s Flight, were carted away as architectural nostalgia, but otherwise an extraordinary history was promptly razed to the dirt and the shell-shocked inhabitants, mostly old and indigent, pushed across the moat of the Harbor Freeway to die in the tenements of Crown Hill, Bunker Hill’s threadbare twin sister. Irrigated by almost a billion dollars of diverted public taxes, bank towers, law offices, museums, and hotels eventually sprouted from its naked scars, and Bunker Hill was reincarnated as a glitzy command center of the booming Pacific Rim economy. Where hard men and their molls once plotted to rob banks, banks now plotted to rob the world. (2001: 36–7, 43)

The main difference between Andersen’s and Davis’s accounts is the quantity and density of information that they contain. Apparently, Davis offers more data – after all, he has twelve pages to do it – while Andersen synthesises the same ideas in five minutes and twenty seconds. But far from being superficial, the filmmaker’s version offers something that the scholar’s lacks: the possibility to see the place before, during and after its transformation. Andersen provides the audience with visual evidences of the process that later became the subject of further research: for example, his vindication of

The Exiles helped to rediscover this film and inspired more detailed analyses of its social and spatial mapping of Bunker Hill (see Gray 2011). This feature, the only one directed by Kent MacKenzie, recorded the mood of the time, when the neighbourhood was already doomed to destruction, and revealed ‘

a place where reality is opaque, where different social orders coexist in the same space without touching each other’. Bunker Hill in

The Exiles is thereby a liminal space that can be perceived and experienced in different ways, depending on who is the observer and what is his or her relationship with the place. Consequently, a good way to depict its changing nature over the second half of the twentieth century is precisely, as Andersen does, to make an inventory of the wide variety of roles that it has played in film.

For progressive historians, the renewal of Bunker Hill symbolises the end of public space in LA, perhaps because it was one of the consequences of the conservative counter-offensive led by the Los Angeles Times in the early 1950s against Mayor Fletcher Bowron’s low-rent public housing programme (see Davis 1990: 122–3). Los Angeles Plays Itself echoes this episode in its third part, exposing the way LAPD chief William H. Parker helped to discredit Frank Wilkinson, Los Angeles City Housing Authority spokesman, by leaking Intelligence Division files that accused him of being a Communist. Once Republican Norris Poulson was elected as new mayor in the 1953 municipal elections, the only public housing that was built was located far from Downtown, in Watts and East Los Angeles, which were respectively the historic ghetto and barrio (see Soja 2000: 134). Accordingly, instead of serving to create an inclusive and heterogeneous community in Chavez Ravine, north of Downtown, the new housing actually increased racial segregation and helped ‘to kill the crowd’, as Davis has stated (1990: 231). Thus, when Andersen describes the California Plaza as ‘a simulated city’, he is complaining about ‘the evacuation of the public realm’, a prerequisite to achieve what Rem Koolhaas ironically termed ‘the serenity of the Generic City’ (Koolhaas & Mau 1995: 1251).

In the last third of the twentieth century, public space was drastically downsized in Los Angeles to make way for non-places such as urban motorways, shopping centres, parking lots or motels. Andersen finds the first signs of this process in Un homme est mort (The Outside Man, Jacques Deray, 1972), in which the main character – ‘a Parisian hit man stranded in Los Angeles’ – has to wander around a city of unfriendly non-places in order to escape the trap set for him. This gradual hardening of the urban surface has been strongly criticised by Davis, who has identified its symptoms in both the real and, above all, the cinematic city:

Contemporary urban theory, whether debating the role of electronic technologies in precipitating ‘postmodern space’, or discussing the dispersion of urban functions across poly-centered metropolitan ‘galaxies’, has been strangely silent about the militarization of city life so grimly visible at the street level. Hollywood’s pop apocalypses and pulp science fiction have been more realistic, and politically perceptive, in representing the programmed hardening of the urban surface in the wake of the social polarizations of the Reagan era. Images of carceral inner cities (

Escape from New York, Running Man)

, high-tech police death squads (

Blade Runner), sentient buildings (

Die Hard), urban bantustans (

They Live), Vietnamlike street wars (

Colors), and so on, only extrapolate from actually existing trends (1990: 223).

5

Many of the films praised as truthful representations in Los Angeles Plays Itself, from The Exiles to The Outside Man, were symptomatically directed by foreign filmmakers. According to their attitude towards Los Angeles, Andersen describes them as ‘low tourist directors’ or ‘high tourist directors’: the first group would be formed by those who avoid or disdain the city, like Alfred Hitchcock or Woody Allen, while the second would include all those who became fascinated by it, namely, Michelangelo Antonioni, John Boorman, Jacques Demy, Jacques Deray, Maya Deren, Alexander Hammid, Tony Richardson or Andy Warhol, among others. Through this distinction, Andersen seems to say that, in a global city like Los Angeles, where there is a clear inflation of images, high tourist directors contribute to problematising its representation beyond the native perspective, because they usually pay attention to places and details that locals underestimate, even though they do not always understand what they are seeing. Arguably, then, the more interwoven the foreign and native gazes are, the more complex the film representation of a city will be.

This may be one of the reasons why the best features about Los Angeles of the 1970s and 1980s, that is,

Chinatown and

Blade Runner, were precisely directed by foreign filmmakers: Roman Polanski and Ridley Scott. In the third part of

Los Angeles Plays Itself, Andersen argues that

Chinatown set a pattern that was later continued by

Who Framed Roger Rabbit and

L.A. Confidential. All these neo-noirs took the city as their main subject, but they wasted the opportunity to express its collective memory by mythologising its past. On the one hand, their narratives reveal the growing self-awareness of the city regarding its social problems: first,

Chinatown criticises both its aggressive water policy and endemic land speculation, although Andersen suggests that the film is actually a displaced vision of the 1965 Watts Riots; then,

Who Framed Roger Rabbit mourns the dismantling of the two old public transport systems in the city – the Pacific Electric and the Los Angeles Railway – in order to support their successor, the Metro Rail, which was under construction in the late 1980s; and finally,

L.A. Confidential bluntly shows police brutality and corruption in the 1950s as an indirect reflection of police work at the worst days of the gang wars of the 1980s and 1990s. On the other hand, the moral of these films does little more than teach that ‘

good intentions are futile’ and that ‘

it is better not to act, even better not to know’, as Andersen states in the film. The last line of

Chinatown – ‘

Forget it, Jake, it’s Chinatown’ – advises the audience to keep away from public affairs, as does the final resolution of

L.A. Confidential. In both films, their respective scandals are not made public, and the characters have to accept their powerlessness. Undoubtedly, a happy ending would have been worse in artistic terms, but at least it would have encouraged citizens to develop a less resigned attitude towards the abuses of power.

In several texts and interviews, Andersen has explained that these kind of films try to convince people that ‘politics is futile and meaningless’ (in Ribas 2012: 92). Obviously, the decision not to talk about politics is always political, because it ultimately serves certain agendas. In this regard, Hollywood is anything but innocent, given that its films have been partly intended for spreading the American way of life all over the world: the smallest detail, as Andersen demonstrates in Los Angeles Play Itself, may be a vehicle of ideology. Then, how to counteract Hollywood’s discourse? What are the features that offer an alternative representation of the city? Most filmmakers are trapped in the same contradiction: ‘It’s hard to make a personal film, based on your own experience, when you’re absurdly overprivileged,’ Andersen says, ‘you tend not to notice the less fortunate, and that’s almost everybody.’ This is to say that Hollywood’s problems in depicting LA, or anywhere else in the world, have to do with its own geographical and social position: if its productions repeat the same spatial clichés this is because Hollywood is too closed in on itself to look beyond its territory.

The main antidote against these misrepresentations would be, according to Andersen, the neorealist cinema that began with The Exiles. For this reason, the final segment of Los Angeles Plays Itself focuses on three titles that belong to the L.A. Rebellion film movement: Killer of Sheep (Charles Burnett, 1977), Bush Mama (Haile Gerima, 1979) and Bless Their Little Hearts (Billy Woodberry, 1984). These films address the plight of the African-American community in South Central Los Angeles in the late 1970s, when the industrial crisis hit the neighbourhood and caused the destruction of thousands of jobs in the area:

Working-class Blacks in the flatlands – where nearly 40 per cent of families live below the poverty line – have faced relentless economic decline. While city resources (to the tune of $2 billion) have been absorbed in financing the corporate renaissance of Downtown, Southcentral L.A. has been markedly disadvantaged even in receipt of anti-poverty assistance, ‘coming in far behind West Los Angeles and the Valley in access to vital human services and job-training funds’ (Curran 1989: 2). Black small businesses have withered for lack of credit or attention from the city, leaving behind only liquor stores and churches. Most tragically, the unionized branch-plant economy toward which working-class Blacks (and Chicanos) had always looked for decent jobs collapsed. As the Los Angeles economy in the 1970s was ‘unplugged’ from the American industrial heartland and rewired to East Asia, non-Anglo workers have borne the brunt of adaptation and sacrifice. The 1978–82 wave of factory closings in the wake of Japanese import penetration and recession, which shuttered ten of the twelve largest non-aerospace plants in Southern California and displaced 75,000 blue-collar workers, erased the ephemeral gains won by blue-collar Blacks between 1965 and 1975. Where local warehouses and factories did not succumb to Asian competition, they fled instead to new industrial parks in the South Bay, northern Orange County or the Inland Empire […] An investigating committee of the California Legislature in 1982 confirmed the resulting economic destruction in Southcentral neighborhoods: unemployment rising by nearly 50 per cent since the early 1970s while community purchasing power fell by a third. (Davis 1990: 304–5)

The films of the L.A. Rebellion put a face to these statistics, conveying the deep despair of African-Americans in view of their worsening living conditions. In this period, many people experienced the industrial crisis as an existential crisis, like the characters of Bush Mama and Bless Their Little Hearts. Iain Chambers has observed that this declassed population has been inserted into discourses that do not help to improve its socio-economic situation: these people do not usually appear in films about their professional success – with the sole exception to date of Chris Gardner, whose rags-to-riches story was adapted in The Pursuit of Happyness (Gabriele Muccino, 2006) – but in narratives about ethnic issues, urban poverty, inner-city decay, industrial decline, drugs or organised crime (1990: 53). Faced with these discourses, independent black filmmakers, many of whom were foreigners in Los Angeles, responded by directing social melodramas focused on family matters, in which they show the everyday struggle to survive in this hostile environment.

Andersen highlights the ‘

spatialized, nonchronological time of meditation and memory’ of these films, a new cinematic time that seeks to fill the gaps of the visual history of African-Americans:

Killer of Sheep, for example, seems ‘

suspended outside of time’ because its director, Charles Burnett, ‘

blended together the decades of his childhood, his youth and his adulthood’. This formal configuration is quite the opposite from that of

Chinatown,

Who Framed Roger Rabbit and

L.A. Confidential: instead of going back to the past to talk about the present,

Killer of Sheep is set in a present which includes memories of the post-war years that had never been represented from the African-American standpoint. This approach raises the issue of who can represent whom. Can Hollywood represent the people from which it actually knows nothing? Can minorities represent anything else than themselves? Andersen avoids this controversy by emphasising the universality of these films: ‘

Independent black filmmakers showed that the real crisis of the black family is simply the crisis of the working class family, white or black, where family values are always at risk because the threat of unemployment is always present.’

Los Angeles Plays Itself ends with a beautiful sequence shot taken from Bless Their Little Hearts in which the main character drives by what Andersen terms ‘a reverse landmark’, the ruins of the old Goodyear Factory on South Central Avenue, the largest tire manufacturing plant in the Los Angeles area, whose closure in 1980 left thousands of unemployed black workers. In Bless Their Little Hearts, this carscape is located towards the middle of the film and symbolically expresses the protagonist’s distress after having lost his job. In Los Angeles Plays Itself, on the contrary, it closes the film and bears up to four different meanings. First, it is a direct quote of Bless Their Little Hearts; second, it echoes its original meaning; third, it explicitly provides a final reflection on the transition from an industrial economy to a service one (‘once upon a time, visitors could take a guided tour and see how tires were made just as today they can take a studio tour and see how movies are made’); and four, it implicitly vindicates those ‘modes of film production opposed to the industry … that grow from the working class itself’, as David E. James has pointed out (2005: 422).

By appropriating these images, Andersen takes sides with a kind of cinema and a kind of city that has nothing to do with the Hollywood urban imaginarium. Therefore,

Los Angeles Plays Itself goes beyond negative criticism against Hollywood’s misrepresentations to reveal the existence of an alternative cinematic city hidden in the neorealist tradition. Andersen certainly provides something more than an illustrated lecture: he offers a model and a tool to think images, as well as an entrance to that alternative cinematic city. Thus, by subjectivising the perception of film heritage, metafilmic strategies create a third space that serves to both preservation and analytical purposes: while

The Decay of Fiction explores the expressive possibilities of the filmic surface;

Los Angeles Plays Itself teaches us, in turn, how to look beyond surfaces, whether urban or filmic, in order to understand what is going on right before our eyes, both in the city and on its infinite screens.

NOTES