t’s not just goat meat. Goat milk is also consumed by more people than any other animal’s milk.

t’s not just goat meat. Goat milk is also consumed by more people than any other animal’s milk.So come along and cross a line. The farmer and the cowman might be friends, if my frontier smarts from Rodgers and Hammerstein hold true. But the goat rancher and the goat dairyman go their separate ways. A dairy farmer doesn’t milk goats until they’re ready for the abattoir.

For one thing, there’s a different ethic. You handle someone’s nipples and you tend not to want to kill them. (Unless their in-laws get involved.)

More importantly, dairy goats produce copious amounts of milk over the years. They get rather stringy and spent. They’re not the best choice for butchering.

The goats’ amazing milk production without any helping hormones, combined with their general lack of fussiness and their ability to manage pastures without stripping them bare, makes up only part of the story behind their global dominance. The rest lies with the milk’s digestibility—or, more specifically, with the structure of the milk fat.

The individual fat molecules in goat milk are very small, a little more than half the size of the fat molecules in cow milk. Specifically, they’re about two micrometers across, or 0.002 millimeter. For those of you who refuse to join the One World, United Nations conspiracy called the metric system, that’s 0.0000788 inch. For those of you involved in Civil War reenactments, that’s 0.000000794 rod.

Tiny, they can crowd in, like grandmothers at a free buffet. On average, 8 ounces (225 g) of whole goat milk has about 10 grams of fat.

More importantly, given the goat-fat globules’ Lilliputian size, they’re easy to digest. Put crudely, they break down quickly, passing on before fermenting.

They also don’t clump—all because of a missing protein called agglutinin. Cows produce it; goats don’t. It permits the fat in cow milk to gather into luscious clots of cream. Since goat milk lacks agglutinin, the fat rarely clots. It’s evenly distributed throughout the milk. The cream may eventually rise to the top, but very slowly and not all of it.

The absence of agglutinin also explains why you’ll rarely see fat-free goat milk at your supermarket. Making even low-fat goat milk is a chore. You can’t just skim it. Rather, the milk has to be centrifuged—that is, spun in a high-speed chamber until the fat is pulled out of suspension. It’s labor-intensive and costly, so you’ll almost never see goat cream at your supermarket. What little can be extracted goes to goat butter.

But it’s not just the fat. The proteins in goat milk are easy to digest because they are short- to mid-size in their strandlike chains. As such, they form a softer curd than those in cow milk. We’ll get to more of this in the next chapter. For now, suffice it to say that a curd is a coagulated protein structure, trapping the fat globules almost by accident. The proteins ball up in the presence of an acid. Stir lemon juice into milk, and you’ll see the curds forms. Add the acids in your stomach, and you’ve got a similar thing going on. Goat milk proteins, when combined with your stomach’s acids, don’t immediately seize into balls that take more effort to digest.

One other difference, while we’re on the subject. Goat milk has 13 percent more calcium, 47 percent more vitamin A, and a whopping 137 percent more potassium than cow milk. Has your doctor told you that you need more potassium? Drink goat milk. (But in all fairness, cow milk has 500 percent more vitamin B-12 and 1,000 percent (!) more folic acid. Which is why goat milk, when given to infants, must then be supplemented with folic acid.)

Goat milk, cow milk—listen, they’re both nutritional wonders. Yet when people first taste goat milk, they often have one reaction: tangy.

I forswear that word. First off, it’s a cliché. But mostly, I don’t know that it’s true.

What is true is that goat milk has an expanded range of flavors—or to use the current culinary jargon, a bigger flavor profile. Taste it. Carefully. That is, a slow sip, held in your mouth a moment while you pull air over your tongue. You’ll experience grass, spinach, meat, wheat, beer, and (yes) lemon.

Thus, goat milk and yogurt recipes have to be crafted with a broader range of flavors in mind.

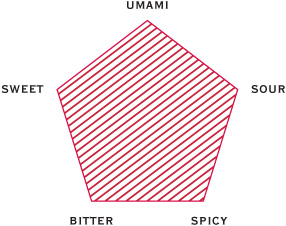

Think of it this way: A good recipe is a five-sided piece of plywood, a pentagon, with sweet, sour, bitter, spicy, and umami as each of the points.

If you’re not familiar with umami (Japanese,  , oo-MAH-mee, meaning “flavor” or “taste”), it’s the basic taste of meat, mushrooms, and good broth: savory, rich, and dense. Long a recognized taste profile in Japan, it’s now been given research creds to prove its validity.

, oo-MAH-mee, meaning “flavor” or “taste”), it’s the basic taste of meat, mushrooms, and good broth: savory, rich, and dense. Long a recognized taste profile in Japan, it’s now been given research creds to prove its validity.

OK, now imagine our pentagon tipping one way or the other in any recipe based on the ingredients, then your having to rebalance it by loading flavors onto various other points.

For example, there’s a lot of sour in a lemon meringue pie, so you have to balance that taste with sweet (the sugar) as well as some bitter undertones (the grated zest).

Or what about a stew with goat meat and sweet potatoes? You know automatically that you’ve got heavy weights on the umami and sweet points of that pentagon. Bitter is probably not the best counterbalance, although a little might help. A better place for the weight is the spicy corner, thereby pulling the stew back to an even keel.

Seems simple enough, right? It isn’t. There’s a complication. Our culinary pentagon isn’t sitting on a flat surface. Instead, it tips this way and that because it’s sitting on a fulcrum—that is, the fat in the dish, the point on which the whole structure balances.

If the fat is a flavorless oil like safflower oil, the fulcrum is pretty much under the center of the pentagon, all things being equal. But if the fat is butter, then the fulcrum is no longer directly under the pentagon’s center. Instead, it’s skewed a little toward the sour point. If the fat is lard, the fulcrum is skewed quite a bit toward the umami point. (Which is why sweet fruit pies made with a lard crust are so frickin’ irresistible.) If the fat is almond oil, the fulcrum moves just slightly toward the sweet point. And if it’s solid vegetable shortening, the fulcrum is back to a neutral, center point.

Thus, when the fulcrum moves off center, the ingredients lying on top of our flavor pentagon have to be even more heavily weighted one way or another to compensate and balance the dish.

Without a doubt, the fat in goat butter, milk, or even yogurt skews that fulcrum toward a point somewhere more on an axis with the sour and umami points. So a balanced recipe weights the ingredients on the top of our pentagon toward the spicy, bitter, or sweet point—as in the Creamy Carrot-Dill Soup (this page): lots of sweet (softened onions, carrots) and a little bitter (dill) for a counterpoint to the goat butter and goat milk.

In the end, recipes that use goat butter, milk, or yogurt require a more sophisticated balancing act than those that use relatively neutral, flavorless oils. And there’s the real rub: In the United States, we’re used to working with neutral tastes like boneless, skinless chicken breasts, all-purpose flour, and even diminished herbs and spices.

If there’s one thing Bruce and I want to preach in this tour of the goatapedia, it’s that neutral tastes and flavors are not to be commended. Nor are they to be condemned. Neutral is useful as a culinary tool. But rarely. It is not as powerful as deep, sophisticated flavors—like those found in goat milk and yogurt. Using them, we’ll be forced to use bolder ingredients, so we’ll discover more flavor in every bite. True satiety is found right there. Always has been. We’ve just forgotten it. Until now.