WHEN BELA AYKLER was three, he wouldn’t go to sleep unless his pesztonka, his sixteen-year-old babysitter, lay down next to him. He loved the smell of her hair, the softness of her skin, and he would wrap his fingers around her plump, blond ringlets and put his face right next to hers until he fell asleep. As the baby of the family, his mother, Karola, doted on him. Little Bela’s world was full of fascination and discovery, and his bedroom had shelf upon shelf of children’s books he could explore. But very quickly he learned to pass over the stories of gnomes, witches, princesses, and dragons and went directly to the stories of great battles and conflicts. He loved military history from an early age, whether tales of Roman legionnaires or Napoleon’s conquests, and dreamt of knights and great battles of valour and glory.

He would plead with his mother to tell and retell the story of one of his great, great, great granduncles who had helped to defend the fortress of Szigetvar against the Turks. Over and over she read to him about the siege that lasted for years and the endless onslaught of fierce, turbaned warriors with black eyes who clashed with the brave Magyar officers and their men defending the fortress. When they ran out of cannonballs, his mother told him, the Magyars poured vats of boiling tar and water on the heads of their enemies. The Turks, in turn, formed a human tourniquet around the fortress and blockaded anyone or anything from getting in or out. Eventually, the defenders ran out of ammunition and were being slowly starved to death. When it became impossible to continue, the warriors who remained inside the fortress made a pact. Instead of waiting for the inevitable surrender or slaughter, they rode out of the fortress in a blaze of glory, knowing they were facing imminent but mercifully quick death.

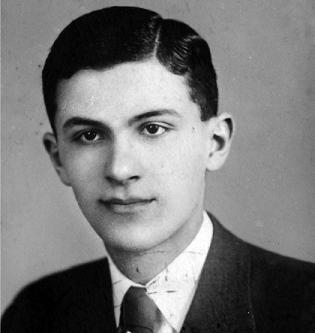

Tibor Schroeder as a young man.

Bela’s brown eyes would open wide as he listened, rapt with emotion, to his mother’s story. His ancestor had been one of those brave warriors, a captain who rode out alongside the fortress commander Miklos Zrinyi on that final day. He never grew tired of this tale and knew that, one day, he would follow in the footsteps of his father, grandfather, and great-great-great-granduncle and would become a professional soldier, a great warrior, as many generations of his family had been before him since 1525 in Bavaria.

When he turned six and could read for himself, his favourite stories were of the Wild West — stories by Karl May about Winnetou, the wise Chief of the Apache Tribe, and Old Shatterhand his white blood-brother. By the age of eight, he had begun organizing the neighbourhood boys into elaborate games of cowboys and Indians. Bela always wanted to be an Indian. He made a deliberate decision to be on the side of the underdogs because he identified with them. He felt a great affinity with the side that was outnumbered, outgunned, squeezed out of their native land, and living in a country where they were not welcome because they were part of a different tribe.

When two local bullies, the Balsai boys, pummelled his best friend Istvan Hokky and split his upper lip, Bela vowed revenge. Istvan was skinny, wore glasses, and was often sick with earaches and nosebleeds. Bela, on the other hand, was pudgy and strong, even as a young boy. He was incensed that the two bullies would attack his weak friend and knew in his heart they wouldn’t have dared touch Istvan if he had been around.

The Balsai boys often used a path that went through his family’s vineyard to get to their summer house. Bela devised an elaborate plan to pay back the bullies. He organized all his friends, luring them over to his house in the afternoons after school to play cowboys and Indians, and waited. On a particularly bright and crisp fall afternoon, the Balsai brothers finally came walking through and were ambushed by a half dozen of Bela’s “army” who tied them by the arms to a branch of a tree and left them there with their feet dangling. By the time the overseer, Mihaly bacsi, heard the blood-curdling screams of the captives and came to their rescue, the fire Bela and the gang had set underneath them was already smoking their feet.

Bela wasn’t intimidated by the punishment he would receive. The satisfaction of knowing he had evened the score for his friend Istvan made it all worthwhile. They had succeeded in smoking out the enemy by exactly the same methods the Indians utilized on the white men who massacred Indians or encroached on their land. He knew the Balsai boys would never intimidate them again.

Bela lived with his parents, his older brothers, Istvan and Tibor, and older sister, Picke, in a big house on the side of a hill, their vineyards extending in every direction. For Bela, their home was an amazing place and their land was magnificent with its own streams and forest. The property bordered on the ruin of the fourteenth-century Kanko Castle, whose stone foundation and partial remnants were owned by the Perenyi family. Bela considered it his own private haunted fiefdom, where he and his friends, or the “army of liberation” as they liked to call themselves, played in the old ruins and re-enacted the many stories and legends they heard about the place. According to local lore, a famous Franciscan monk was buried there, a priest who had led the charge against the Turks in a place called Nandorfehervar. When he died, his supporters had smuggled his body back here for safe burial. Another local legend claimed that a few renegade Franciscans had once kidnapped a beautiful young Perenyi girl from the baron’s estate and held her captive in the castle.

Bela’s grandfather and mother ran the winery and he knew from a very early age that growing grapes was a meticulous, time-consuming occupation. At various times of the year there were hundreds of workers who arrived from the surrounding hillside districts to help in the planting, separating, covering up, weeding, and harvesting of the grapes. Young Bela looked up to his tall, distinguished-looking grandfather and would follow him along as he directed the work to be done in the vineyards. He loved the sound of Grandfather’s melodious, calm voice as he provided direction and inquired about the progress of the work.

When merchants arrived at the house wanting to buy grapes or wine, Bela knew that if he wanted to stay in the room, he had to be very quiet. He sat patiently, not uttering a word, bewitched by the way his grandfather firmly and quietly negotiated with the purchasers. The most interesting buyers were men who Grandfather called Ortodox Zsidok (Orthodox Jews). They had long beards like Bela’s father but curly sideburns as well. The Jews not only bought the grapes but insisted on pressing them the old-fashioned way: by foot. Bela always sat close by and watched the rhythm of their movements, listening as they sang their fascinating songs. They would come in threes and the men would roll up their loose pant legs and get into the vat full of grapes. They held on to each other’s shoulders and sang in a language that Grandfather said was called Hebrew as they crushed the grapes to make their special kosher wine. Grandfather told Bela that although their religion was different, these Jews were Hungarians and had stayed loyal to Hungary, even after the borders were changed. At Easter time, Jewish women brought freshly baked sheets of paszka (matzo) to the house as gifts for his grandfather. Bela loved to bite into the crispy treats.

But Bela only realized how many people loved his grandfather when he passed away. The wake was held at the house and Bela, barely four years old, sat perched at the top of the staircase watching as long rows of neighbours and friends came to pay their respects. It seemed the lines lasted days. When they took the coffin away to the cemetery in a fancy horse-drawn carriage, Bela was allowed to sit in the front with the coachman. The seat was high and he was amazed at how much he could see from above. He felt very important sitting up there, not quite realizing at such a young age what it was all about.

After his grandfather died, the full house he was used to as a child began to change. First, his dearly loved older brother, Tibor, went away to high school in nearby Kassa. There were ten years between them. Although Tibor was already a teenager when Bela was growing up, he always made time for his little brother. Tibor pursued hobbies that were out of the ordinary, like photography and assembling ham radio receivers. Everything Tibor did fascinated Bela. Tibor owned an attention-grabbing motorcycle and taught himself how to disassemble and reassemble the motor. Bela swooned at the chance to grab a ride on the motorbike with his brother. Bela sat behind Tibor, wore a special safety helmet, and hung on to his brother’s waist for exhilarating rides in the countryside.

Tibor also dated the best-looking girls. The estate had a guest bungalow more than a kilometre up from the main house, a cozy place with sleeping accommodations in three bedrooms and an expansive patio balcony. Tibor frequently took young ladies up to the guest house. Bela wasn’t sure what they were doing up there, but Tibor made his little brother promise not to tell their mother about the mysterious female guests and vowed to make earlier and more frequent payments in ice cream.

When Bela’s older sister, Picke, turned thirteen, she went away to school as well, first in Beregszasz, and then later in Munkacs. Bela was seven at the time and was attending a primary school in Nagyszollos at the Catholic elementary school. He really missed her when she left. She was closest to him in age, just four years older, and they got along well except when he teased her about her blossoming breasts and boyfriends — always in front of her friends, of course.

His father, Domokos, was also rarely at home. Bela felt instinctively, as a child does, that there was something wrong. Bela saw that his mother often wiped away tears when he asked where his father was. He knew it had something to do with the Czechs. He hadn’t actually met any Czech children — there were none in the Catholic and later Polgari school he attended or among the Rusyn boys he played with. The only contact he had with Czechs was with the stern detectives who sometimes came to search the house. His mother told him they were looking for guns and ammunition. Then the Czech detectives took his father away for interrogations and Mother said they did this because the family was Hungarian.

After they took Father away, the house searches became more frequent. Sometimes as many as twenty detectives descended on the house. They would rummage around the house, two searching each room, emptying drawers, desks, armoires, closets, and trunks, often overturning mattresses, tossing everything on the floor. Once, Bela came home to find all of the storybooks in his bedroom scattered on the floor. Sometimes the searches went on relentlessly all day, sometimes they lasted just for a few hours. The detectives searched the packing houses and stables as well, and ordering all the employees out of the distillery while they rummaged through each nook and cranny of the buildings. While the house and grounds were being searched, his mother was taken away to a separate room and questioned for hours by two or three detectives.

One rainy afternoon, Bela arrived home from school to find the front door bolted from the inside. Several Tatra cars were parked ominously in front and he knew the detectives were inside conducting their searches again. His mother had locked the front door from the inside as a prearranged signal. It meant that Bela should go to the neighbours’ house until the search was over. But Bela’s curiosity got the better of him and he thought maybe he could distract the detectives by being inside the house, so he crawled in through the lower-level bathroom window. This was something he did quite often, especially when he forgot to take his key. But it was a rare occasion that no one was at home. Usually Mother or Anna neni, the cook, would be waiting for him with a glass of milk and a freshly baked fank (donut) or kalacs (cinnamon bun).

Once inside, he inched his way toward the main front entranceway and, without making a sound, crept into the living room where two detectives were scouring the drawers and bookcases. One of them had taken a particular interest in Bela’s toy soldier collection, which Mother had let him set up in one corner of the living room so that he could be near her when he played. Bela looked sadly now at the elaborate battlefield he had created with hundreds of toy soldiers, bridges, barricades, cannons, horses, and a fortress. One of the detectives, whose wire-rimmed glasses sat on the rim of his very straight nose, was examining the battlefield intently. The detective picked up a toy soldier — a flag bearer who was a particular favourite of Bela’s — and was studying the flag held by the miniature figure. Bela had painted the flag red, white, and green, using toothpicks to put the tiny bits of colour on the rubber flag. He knew it was forbidden by law to display the Hungarian tricolour in Czechoslovakia, but the toy soldier was small, only about three centimetres tall, so the flag was tiny.

When the detective spotted Bela, he turned to him and asked the obvious: “And whose toy soldiers are these?”

Bela scanned the meticulously assembled battlefield and exclaimed proudly, “They’re mine!”

Suddenly, the detective’s face turned red with anger. Still holding the toy soldier in one hand, he raised his other hand and slapped Bela across the face with such force that the eight-year-old flew across the room, landing at the edge of a chaise-lounge and hitting his head. The pain of the slap was searing into his face, his head was pounding from the blow, the shock of it all was already stinging his eyes, but despite all, Bela was determined not to cry or yell out. As he instinctively put his hand up to the spot on the side of his head where he hit the furniture, he felt a bit of blood. The phrase “Never let the enemy know how much they have injured you” popped into his brain. He remembered it from one of his books. He conjured up the most hateful look he could muster and glowered at the detective in anger, determined that someday, when he grew up, he would repay this horrible man.

The detective studied the boy’s contorted face and, in broken Hungarian, growled at him, “You could kill me, couldn’t you, you little shit?”

At that moment, the senior detective entered the room with Karola, asking her questions as they walked. They both stopped and stared at the child fighting back tears on the floor, a red welt streaked across his face. The embarrassed detective noticed them and hurriedly placed the toy soldier back with the others. The head of the search team made a show of looking around but ignored the incident and kept talking to Karola as if nothing had happened. She, however, turned white when she saw Bela and clasped her hands together, heading straight to the child.

“What happened to your face, darling?” she exclaimed.

The head detective grabbed her by the elbow and kept talking, hoping that what she had seen would frighten her into telling them what they wanted her to confess. But she had stopped listening. She seemed to shut down as she stared at her young son, both of them silent and passive, frozen to the spot. The head detective finally ordered the group to leave, seeing that no confessions would be forthcoming today from the wife of the man they wanted to indict. When they left, Karola gathered her son in her arms and they sat huddled together on the carpet, each crying bitter tears and comforting one another.