Introduction

Successful surgery relies on proper wound healing and tissue repair. When these processes do not follow their normal pattern, urological surgeons may be faced with complications including skin separation, wound dehiscence, tissue necrosis, and breakdown of vascular, urinary and parenchymal structures. Determinants of proper surgical healing include preservation of critical anatomical structures; restoration of tissue integrity and homeostasis; and the regenerative potential of tissues. In addition, the surgeon must have a detailed knowledge of previous surgical, traumatic, infectious, and radiation related perturbations to normal anatomy and physiology, along with an understanding of the time course and vulnerability of tissues after injury in order to properly plan for successful primary repair or tissue transfer to achieve restoration of function.

gross anatomy with particular emphasis on the vascular supply of skin, subcutaneous tissue, fascia, muscle and individual organs.

understanding of the microvasculature of skin and epithelia, which support the primary barrier functions of the body.

cellular and tissue events in restoring tissue integrity.

proper harvesting of free grafts and the process and timeline of tissue engraftment, for cases when tissue transfer cannot be accomplished with a vascularized flap.

flap creation, which relies on the intrinsic vascular anatomy of the tissue, propensity for collateral formation, and in cases of replantation or free flaps, the timeline for perfusion and reperfusion.

Gross and Vascular Anatomy

Genitourinary tract organs vary in their response to injury and “success” in wound healing in proportion to the density and/or redundancy of their blood supply. In any organ, matched arterial inflow and venous outflow are required for wound healing, and congestion of the venous outflow can just as certainly, although more slowly, doom the success of a tissue transfer or surgical procedure as arterial occlusion. In this section, we will work from cephalad to caudad to review how anatomical knowledge informs surgical principles and patient care.

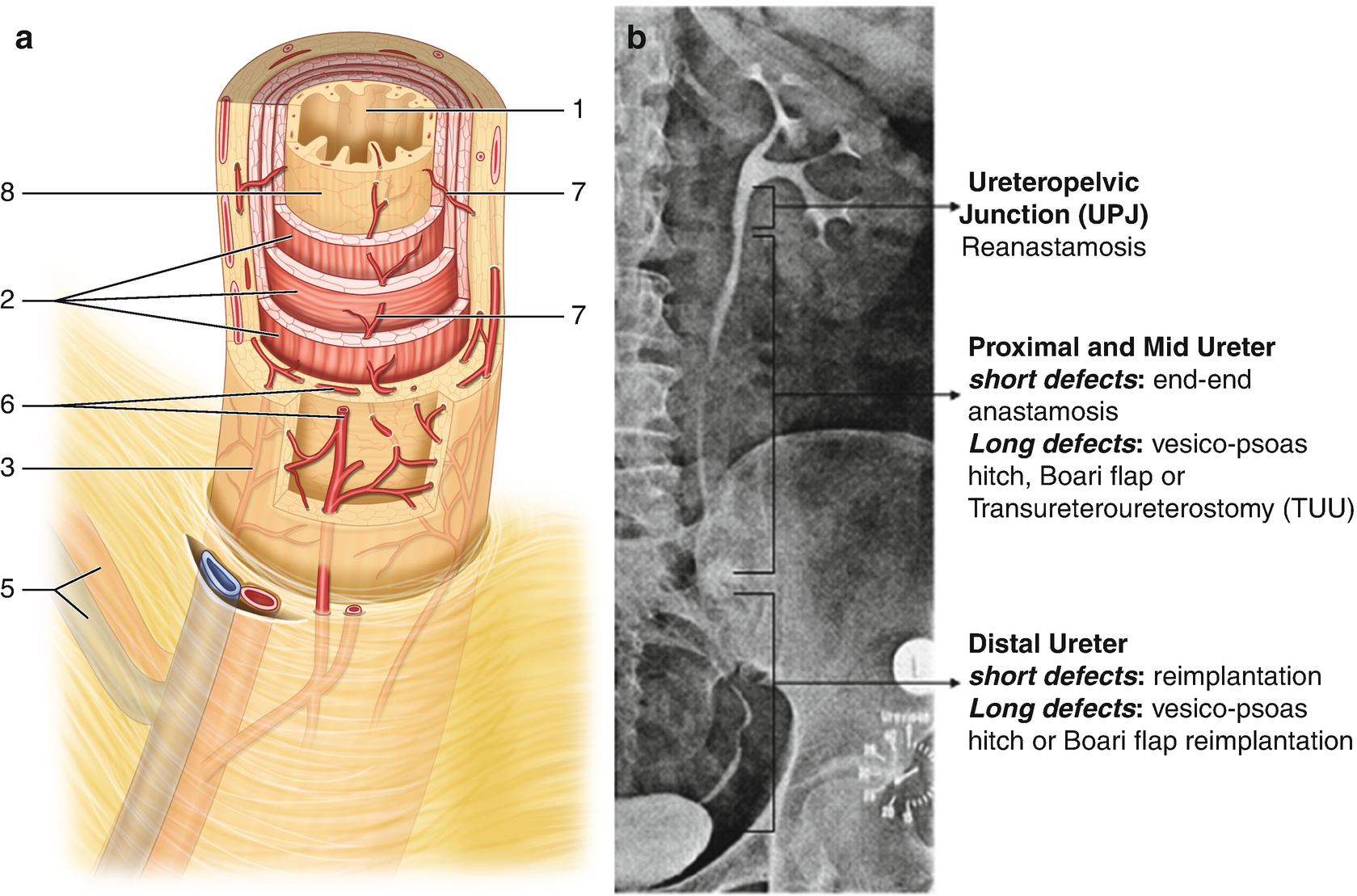

Ureteral vascular architecture . (a) schematic drawing of vascular plexus (drawn from Ref. [3]) demonstrating adventitial vascular plexus; perforators; and mucosal vascular plexus. 1- urothelium, 2 - muscular wall, 3 - adventitia, 5 - segmental arterial and venous supply, 6 - adventitial vascular plexus, 7 - perforating arteries, 8 - mucosal vascular plexus. (b) ureteral vascular regions and impact on reconstruction

Ureteral surgery depends on the vascular network within the ureteral wall for its safe mobilization and effective use in reconstruction (Fig. 15.1) [3]. An adventitial vascular plexus receives arterial supply from a number of points along the ureteral course including the renal artery, the aorta, iliac artery and its pelvic branches. These perforate through the muscular layers to reach the mucosal vascular plexus . The ureter thus has a variable propensity for ischemia like any flap; ureteral healing depending on the amount of mobilization, the distance from its next perforating arterial branch, and preexisting or intraoperative damage to its vascularity from fibrosis, radiation or improper manipulation. These considerations greatly influence the choice of ureteral reconstructive strategy, from pyeloplasty and ureteroureterostomy when both ends are healthy, to reimplantation or substitution. Figure 15.1 provides the divisions of ureteral vascular zones and appropriate reconstructive strategies. The portion of the ureter crossing the iliac vessels and more distal is considered in a watershed area, and less reliably supports ureteroureterostomy; reimplantation is preferred whenever possible in the lower 1/3 of its course.

The bladder and prostate are resistant to ischemic complications, in part because of redundant blood supply (see chapter on anatomy of the pelvic organs), a relatively low metabolic demand compared to other organs (such as the kidney or testis) and the robust interconnected intrinsic vasculature which allows for collateral flow beneath the epithelium. Bladder ischemic damage results from longstanding outlet obstruction, chronic inflammation or pelvic irradiation. Its usual manifestation is in a loss of compliance and elasticity, making it difficult to reconfigure for reconstructive purposes such as a Psoas hitch, Boari flap, Y–V plasty or bladder tube formation. Circumstances in which prostatic ischemia are relevant to wound healing predominantly relate to prior radiation therapy [4, 5], in which obliterative endarteritis leads to inadequate reepithelialization of the prostatic fossa and development of fibrosis, heterotopic calcifications and refractory stenoses. Rarely, severe ischemic complications of pelvic fracture including vascular injury or embolization may lead to prostatic or membranous urethral necrosis.

The male external genitalia and urethra benefit from a highly redundant vascular supply possibly reflecting the evolutionary importance of reproductive success [6]. The posterior urethra receives inflow through branches of the inferior vesical artery perforating through the bladder neck and prostate, while the anterior urethra is served by multiple branches of the internal pudendal artery. These include bilateral direct flow from the bulbourethral, with important collateral supply from the dorsal arteries (via anastomoses in the glans) as well the deep or cavernosal artery (via perforators from the corpora cavernosa to the spongiosum). Importantly, the watershed between posterior and anterior urethra is the membranous urethra, which explains why radiotherapy related strictures fall predominantly in this location. Urethral vascular anatomy informs reconstructive strategies in pediatric and adult urological surgery such as division of the urethral plate during anastomotic urethroplasty or chordee correction, reconstruction of failed hypospadias, staged and one stage substitution procedures, as well as microsurgical revascularization for urethral or erectile problems–beyond the scope of this chapter [7]. Analogously, the penile erectile bodies and glans can be split, separately mobilized, and even transected and reattached yet be expected to heal reliably in the absence of all but the most severe vascular disorders (such as Monckeberg’s calciphylaxis). The ultimate demonstration of the robustness of the penile and urethral vasculature is penile disassembly advocated in selected cases of complete bladder exstrophy and epispadias.

The skin of the external genitalia has a similar redundant blood supply. Penile shaft skin receives primary vascular support from the superficial external pudendal arteries with collateral flow from the bulbourethral and dorsal arteries via the glans. The scrotum receives arterial input from the named arteries off of deep external pudendal arteries as well as anastomoses with the perineal arteries posteriorly. Thus lacerations, burns, surgical incisions, and a variety of random flaps can reliably heal when based on genital skin. An exception to this rule of thumb is the perineum. If the skin is lost through necrotizing soft tissue infection, the underlying perineal soft tissue and fat poorly support skin grafts and often must be left to close by secondary intention or with the support of vascularized tissue transfer.

Tissue Healing Responses

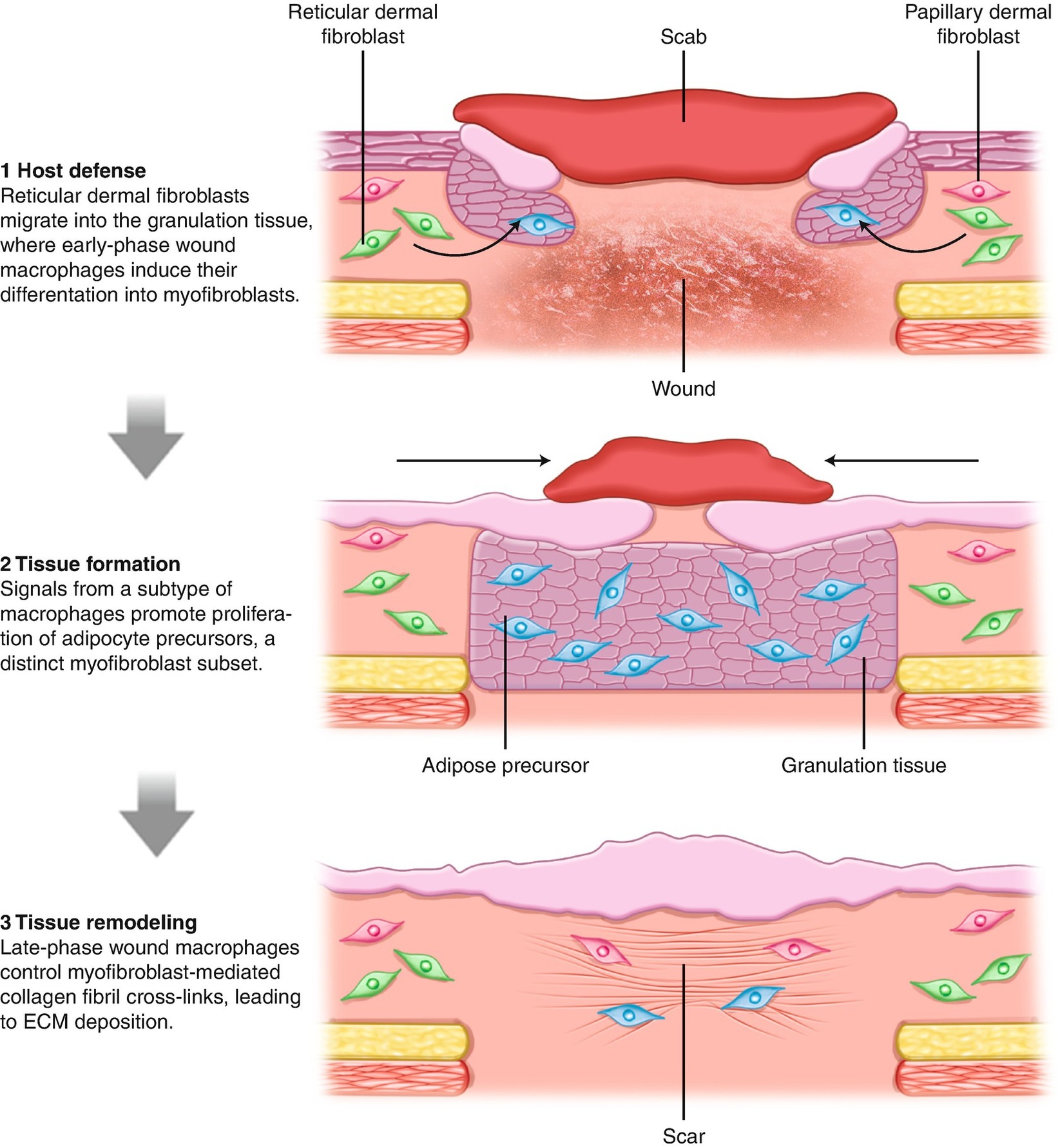

With rare exception of certain organs and fetal tissue, the healing response replaces damaged tissue through the deposition of collagenous connective tissue. Fibrosis to temporarily stabilize newly formed or newly connected tissues is important for healing, but may be perturbed by excessive fibrosis which ultimately impairs tissue function and leads to patient discomfort, loss of function, and even mortality.

Skin wound healing schematic (drawn from Ref. [8]) showing role of dermal fibroblasts and adipocytes in mechanisms of wound healing and scar contraction

Epithelial Microarchitecture and Determinants of Graft Take

Comparison of microanatomy of skin and buccal mucosa grafts. (a) Schematic showing the epithelial and subepithelial layers of normal skin, along with the layers used in full thickness (FTSG) and split thickness (STSG) skin grafts as well as dermal grafts (redrawn from Ref. [6]). (b) Histological section showing interface of adjacent skin (left) and oral mucosa (right) after a staged urethroplasty. Note the cornified surface, thinner epithelium, and deeper subepithelial layer of the skin versus the adjacent oral mucosa which is not cornified

The “take” and ultimate survival of free grafts requires assessment of the properties of the donor site, recipient bed, and general principles of engraftment. Equally important are more subtle factors that bear more on the long-term functionality of the intended graft such as elasticity, thickness, collateral formation and tolerance for tubularization.

Donor site concerns include the above-mentioned discussion of thickness of the lamina propria; the absence of infectious or inflammatory conditions (such as an acute fungal infection or lichen sclerosus); ease of harvesting and availability; cosmetic concerns such as pigmentation matching; and the ability to close the donor site. Recipient bed considerations overwhelmingly relate to the ability to support and vascularize the graft. When a graft is placed on a newly created wound, the inherent characteristics of the recipient bed define the likelihood of successful graft take. Thus, a graft affixed to the normal corporal body, the testis or tunica vaginalis, or a healthy muscle, will have a high chance of take. Conversely, when a recipient site is compromised, such as in complex open wounds from trauma and infection [9], the surgeon must decide whether a period of wound care will clear contamination and allow granulation tissue to form, or instead the patient needs adjunctive measures involving flaps to cover the wound or create a better recipient site.

The steps in revascularization of an epithelial graft have direct influence on patient care decisions [6]. Successful “take” of a free graft requires survival of the epithelium, initially through direct absorption of oxygen and micronutrients from the underlying recipient site. This process of imbibition is thought to last 24–48 h until neovascularization proceeding from the graft bed meets up with the still-living vascular network of the donor tissue. Once inosculation occurs, stable perfusion is generally achieved within another 48 h. Thus, the first 4 days after grafting have the most impact on ultimate graft take. Importantly, certain comorbid conditions including poorly controlled diabetes, cigarette smoking, and severe peripheral vascular disease may influence graft take and must be factored into decision making.

Immobilization of the graft to its recipient site, whether through quilting sutures, dressings, or a combination of both, are beyond the scope of this chapter but must be considered in detail. On a practical note, steps to prevent lifting of the graft off of the recipient site during this critical period are important and may include “pie crusting” or meshing of the graft [10]; fixation as mentioned above, and in certain circumstances, visualization of the graft and de-blebbing.

Additional considerations in graft creation relate to the ultimate functionality required of the grafted tissue. Each surgery must strike a balance between “take”, contracture and elasticity. Autologous grafts, harvested and placed without any treatment or preservation, maintain their elasticity and impart it to the recipient site. Full thickness grafts will undergo minimal shrinkage unless there is graft loss, in which case wound contraction and fibrosis replaces normal epithelium. Conversely, the split thickness skin graft, with its thinner subepithelial connective tissue (see Figure 15.3a) allows better imbibition and inosculation, although the price paid is in the fragility of the skin and higher degree of contraction, stiffness of the tissue, and lesser functionality. Furthermore, how the tissue is laid out and fixed to the recipient bed will influence its later functionality. For example, in a staged urethroplasty an oral mucosa graft may be harvested in a 6 × 3 cm size. However, if the elasticity of the graft is used to achieve greater length, the consequence will be neourethra with less than 3 cm width. Meshing of STSG’s will influence contraction, ranging from a ratio of 1:1 (e.g. no expansion and lesser contraction) up to 1:3 (significant expansion and greater contraction). Grafts also have less supporting soft tissue and may therefore lack bulk or cushioning which may make them less desirable without adjunctive use of underlying muscle or other soft tissue flaps.

A consideration related to grafts is whether skin that has not been adequately prepared (e.g. defatted) can serve as a graft, Skin flaps, if cut off from their blood supply, generally will not survive as a free graft because the underlying or adjacent pedicle provides too thick of a barrier to events during revascularization, and as a result leads to ischemic loss. Analogously, genital shaft skin which has been avulsed in an injury may have suffered damage to its dermal network of arteries and veins. Thus, the classic “power takeoff injury” in which the entire penile and scrotal skin is avulsed in rotating machinery, likely has suffered shearing injury to its intrinsic vasculature and should only be used as a free graft with caution.

Vascularized Flaps and Genitourinary Tissue Transfer

All flaps are vascularized. The author nevertheless prefers the redundant term to emphasize the essential difference between flaps and free grafts. When free grafts are not appropriate, either due to limited tissue availability, depth of defect, or inadequate recipient site vascularity to support engraftment, flaps offer solutions for the care of patients with severe injury, cancer, surgical complications, and necrotizing soft tissue infection. Vascularized flaps can fill a defect in an organ, cover vulnerable structures, or in certain circumstances support a graft in an area of poor vascular supply.

Principles of flaps . (a) Classification of random, axial, pedicle and free flaps (drawn from Ref. [6]). Illustrative examples: (b) Random flap—anterior bladder tube; (c) Axial flap—longitudinally split and lateralized corpus spongiosum/urethral plate, upper and lower images before and after placement of oral mucosa grafts respectively; (d) Pedicle flap—penile fasciocutaneous flap; (e) Free flap—radial forearm phallic construct

Random flaps are used frequently in urology, whether by taking a spiral renal pelvic flap; creating a bladder flap to bridge a defect, stricture or a fistula; use of a Boari flap for ureteral reimplantation; or any number of penile and scrotal skin advancements used to cover defects related to hypospadias, injury, necrotizing skin loss, and the like. In these cases, the most important principle is creating proper length-to-width ratio, in which a given length of a flap survives based on the proportional width of pedicle. Generally, a random flap should be no longer than 3 times its width. Whether to create a flap as a rectangle, U, or triangular, depends on the expected robustness of the intrinsic blood supply of the tissue to be transferred. Axial flaps have a known and reliable underlying arterial pattern, which allows for predictable vascularization of the leading edge of the flap and a different length-to-width ratio. Finally, pedicle flaps, whether supported by a very robust arcade of vessels or a single blood vessel, can be moved greater distances because they do not rely on connection of the overlying skin or epithelial structure. Taken to its extreme form, this is the essence of a free flap with microvascular anastomosis: when the pedicle is not long enough to reach the intended recipient site, division and anastomosis to new arterial and venous structures is required at a new location.

Synthesis

Microvascular penile replantation . (a) Urethral anastomosis, after placement of ventral wall sutures. (b) Corporal reapproximation in progress. (c) Completed corporal reanastomosis. (d) Microvascular anastomoses of vein (arrowhead), artery (arrow), and nerve (long arrow)

Summary

The genitourinary system consists of specialized epithelial and stromal aggregations that carry out vital excretory and reproductive functions. When disrupted, function of these organs can be successfully restored applying principles of tissue transfer in the context of anatomical knowledge and an understanding of the processes of wound healing. Unfortunately, no current technology provides readily available robust means of assessing the vascular status of a recipient bed, mobilized flap, or adjacent tissue edge. Emerging technology such as vital imaging during robotic surgery with fluorescence dyes [11, 12] represents one advance, which if validated, and shown to improve outcomes, may diffuse to a wider set of users. For the time being, close adherence to the principles outlined in this chapter will provide the reader with a framework from which to make surgical decisions in the face of uncertainty. The ensuing chapters in this textbook show the application of these concepts across the full range of urological surgery.