CHAPTER III — MECHANICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF TANKS

THE following very brief account of the mechanical characteristics of tanks, it is hoped, will prove sufficiently simple and complete to give to the non-mechanical reader some idea of the tank as a machine.

THE MARK I TANK (see Frontispiece)

The first British tank made, and to be used, was the heavy machine, already described in the previous chapter, the Mark I tank, the general outline of which remained the standard design for the hulls of all British heavy machines up to the end of the war. As will be shown later, many mechanical improvements, making for higher efficiency and greater simplicity of control, were introduced from time to time, but the fact remains

that the profile of the Mark V tank of 1918 was to all intents and purposes that of the Mark I of 1916, and surely this is a striking tribute to the genius of the designers who, without much previous data upon which to base their work, produced the parent weapon.

It is not proposed here to enter upon the general arrangement of the Mark I tank, but reference to two important points in design is of interest. The first is that this machine was fitted with a “tail,” consisting of a pair of heavy large-diameter wheels, mounted at the rear of the machine upon a carriage, which was pivoted to the hull in such a manner that the wheels were free to follow the varying contours of the ground. A number of strong springs normally kept the wheels bearing heavily upon the ground, whilst a hydraulic ram, operated by an oil pump driven from the engine, was intended to enable the carriage to be rocked upon its axis, in order to raise the wheels well clear of the ground on occasions when it was necessary to “swing” the tank

.

The object of this “tail” device was to provide means of steering the machine and, to this end, the driver was provided with a steering wheel which, operating a wire cable over a bobbin or drum, altered the path of the “tail” wheels, and allowed the tank to be steered, under favourable conditions, through a circle having a diameter of about sixty yards. The disadvantages of this fitting far outweighed any virtues it may have possessed. Countless troubles were experienced with the ram and its pump; the wire steering cable was constantly stretching or slipping through the bobbin, thus affecting the “lock” of the tail wheels; the driver was subjected to great physical strain in overcoming the tremendous resistance offered by the road wheels; the whole device was very prone to be damaged by shell-fire in action. Against these indictments should be recorded the fact that the possession of a “tail” enabled the Mark I tank successfully to span and cross a wider trench than the later “tailless” machines of the same dimensions could negotiate, owing to the fact that

as the wheels supported the rear of the tank over the point of balance, the risk of “tail dive” was considerably reduced. However, at the close of the operations of 1916, all tanks were shorn of their tails, and no subsequent models were fitted with them.

The second point of interest regarding this early machine relates to its sponsons. These, on both the male and female machines (armed with full length 6-pounder and Vickers machine-guns respectively) were planted upon and bolted to the walls of the hull and, for entraining purposes, these had to be removed and carried upon special trolleys which could be towed behind the tanks. It will readily be seen that this arrangement involved a considerable amount of labour, and rendered the process of entraining an extremely lengthy one; this led to an improved form of sponson being produced for the Mark IV machine.

The chief outstanding weaknesses of the Mark I machine, disclosed during the first appearance in action, were

:

That the engine was provided with no silencer, consequently the noise, sparks, and even flames, which proceeded from the open exhaust pipes, passing through the roof of the tank, constituted a grave danger during the latter stages of an approach march. Many ingenious tank crews fitted to their machines crude types of silencers made out of oil drums, or adopted the plan of damping out the sparks by using wet sacks in relays, or covering the exhaust pipe with clay and mud.

That the observation from the inside of the machine was bad, and efficient fire control was, therefore, impossible.

That the means provided for entering and leaving the tank were unsatisfactory, and, in the case of the female machine, speedy evacuation in the event of fire was difficult.

That the whole of the petrol supply was carried inside the machine, and in a vulnerable position a circumstance which added to the risk of fire in the event of a hit in the petrol tank by armour-piercing bullet or shell. Furthermore, gravity was the only

means for transferring petrol from the main petrol tanks in the front of the machine to the carburettor, and, therefore, it frequently happened that when a tank “ditched” nose downwards, the petrol supply was cut off, and consequently the dangerous practice of “hand-feeding” had to be resorted to.

THE MARK II AND MARK III TANKS

These machines were produced in small numbers, and their difference from Mark I lay in various minor improvements, none of a radical nature.

THE MARK IV TANK (Plate I—see p. 26)

In 1917 this tank became the standard fighting machine of the Tank Corps, and it was used in battle throughout this year and the following. As already stated, in outline it corresponded so closely with the Mark I machine that a study here of the main features of this tank will serve generally as

an illustration of what had taken place in tank development up to this date.

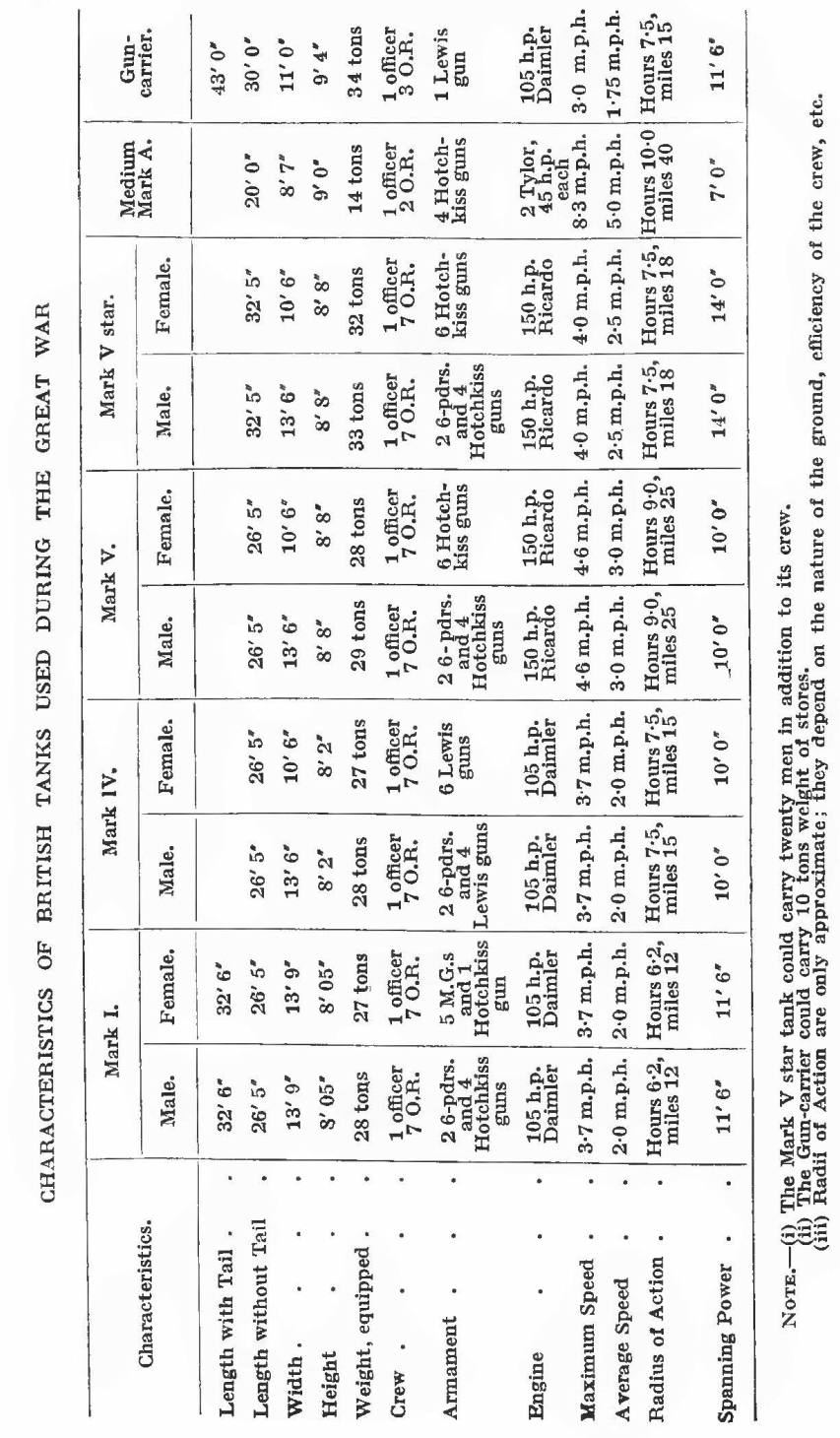

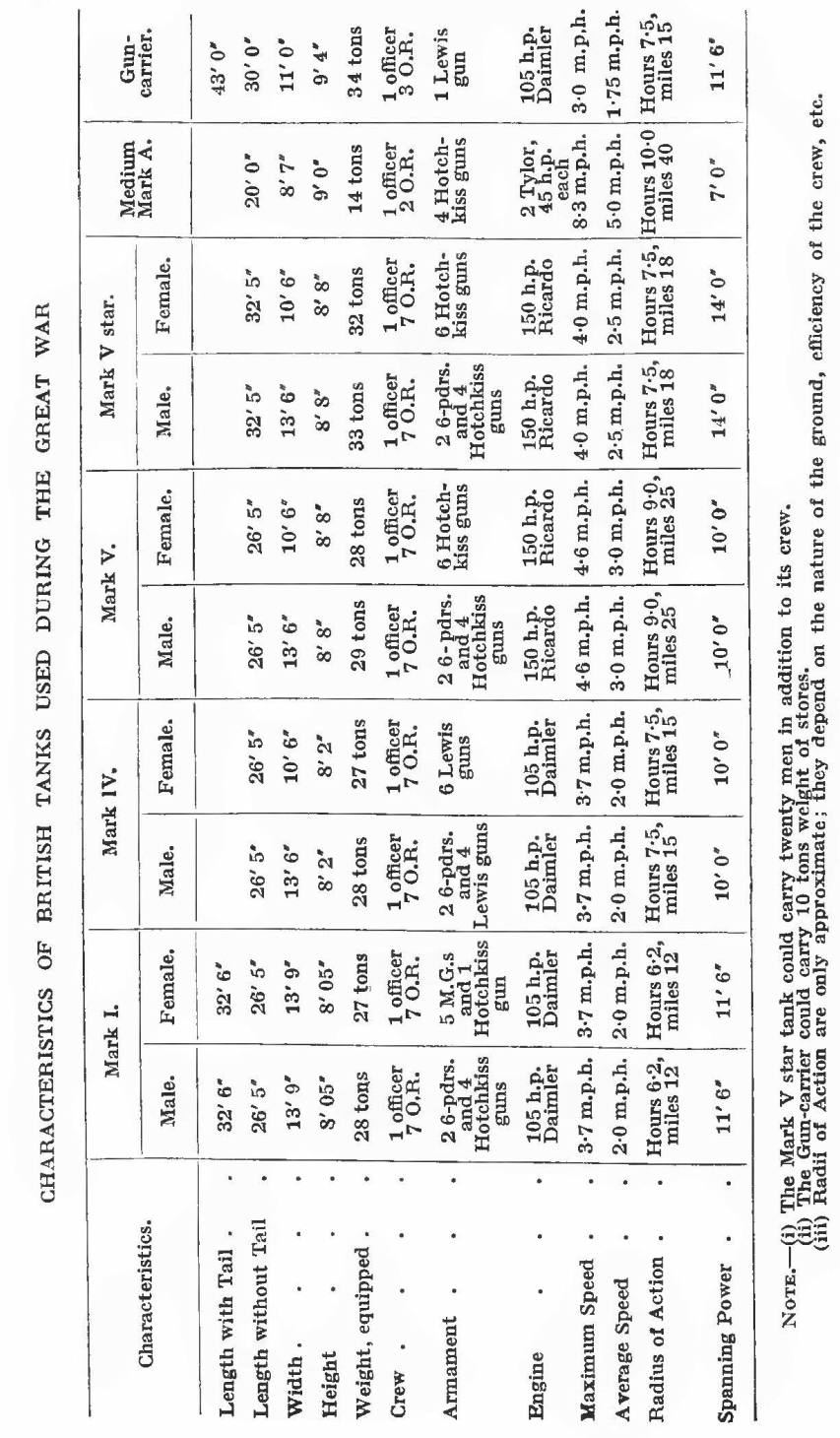

The machine was 26 ft. 5 in. long over all, whilst the width of the female over its sponsons was 10 ft. 6 in., and of the male, 13 ft. 6 in. The height of the machine was 8 ft. 2 in., and its weight, equipped, was 28 tons. The armament consisted, in the case of the male, of two 6-pounder guns and four machine-guns, and in that of the female of six machine-guns; it was fitted with a 105 h.p. Daimler 6-cylinder sleeve-valve engine which, at a later date, was replaced in a limited number by one of 125 h.p. This increased power was obtained by the use of aluminium pistons, twin carburettors, and by speeding up the engine.

Generally speaking, these engines gave very little trouble, although somewhat under-powered for the work they had to perform. They were, it may be added, particularly suitable from the maintenance point of view, owing to their “fool-proof” nature, due chiefly to the absence of the

usual poppet-valve gear, with its attendant risk of maladjustment.

Power was transmitted from the engine flywheel, through a cone-type clutch and a flexible coupling, to a two-speed and reverse gear-box, known as the primary gear, this being under the direct control of the driver, who could thus obtain first and second speeds, or reverse, without other assistance.

The tail-shaft from the gear-box carried a worm which drove the crown wheel of a large reduction gear, this gear also serving as a differential to enable the track driving wheels to rotate at different speeds, as when steering the tank on its track brakes. A device was provided, under the driver’s control, for locking the differential when it was desired to steer a dead-ahead course, or when negotiating a trench or other obstacle. With the differential locked, the gear became, so to speak, “solid” and obviated the risk of one of the tracks slipping in bad ground, a condition very apt to

cause a tank to slip sideways into a trench and become ditched.

Some trouble was caused through breakages of this locking muff in the earlier days, but latterly the arrangement was considerably improved and strengthened.

The gear-box tail-shaft terminated in a brake drum, the band of which was operated by means of a pedal at the driver’s foot. It may be of interest to point out here that the whole of the items so far referred to, i.e.

engine, gear-box, and differential, formed the standard power unit of the pre-war Foster-Daimler tractor, and thus provided a known quantity around which the rest of the detail was designed. This greatly facilitated production.

On either side of the differential case projected cross-shafts, the outer ends of which were supported in bearings mounted upon the outside wall of the tank, and, between the inner and outer walls of the hull, two sliding pinions were carried on a splined portion of the cross-shaft, one pair of

pinions on each of the right and left hand sides of the tank.

In describing the remainder of the transmission, it will suffice to deal only with one side of the machine, the detail on either side being identical.

The sliding pinions, already alluded to, were operated by means of short levers by two gearsmen, whose sole duty it was to assist the driver, who signalled to them his requirements from his seat in the front of the tank, the two gearsmen being accommodated towards the rear of the machine on seats placed over the primary gear-box. The sliding pinions were of two sizes, known as the high-speed and low-speed pinions, and immediately in their rear was mounted another pinion assembly, also carrying two gear-wheels of different dimensions, with which the sliding wheels could be engaged at will in other words, on each side of the tank there existed what were known as secondary gear-boxes, each offering a choice of two speeds.

Thus it will be seen that the whole arrangement provided a range of four speeds. Assuming the

secondary gears to be at “low,” the driver had the option of using either first or second speed by manipulating the control to the primary gear-box, whilst in order to obtain third or fourth (top) speed it was necessary for him to signal the gearsmen to alter their gears to “high,” and to assist them in the process by a great deal of intelligent clutch work. It need hardly be pointed out that this arrangement was exceedingly clumsy, and often involved much loss of time and temper. It might also be mentioned here that the reverse gear, already alluded to, was considerably higher than the lowest forward speed, so that there was little possibility of driving backwards, clear of any obstruction which might have ditched the tank.

Hand-operated brakes, under the control of the tank commander in the front of the tank, alongside the driver, were incorporated with the secondary gear-box. These brakes, by checking one or other track, enabled the tank to be steered in some measure with the differential unlocked, whilst, by locking the differential and placing, say, the right-

hand secondary gear in “neutral,” the machine could be swung to the right, practically upon its own axis, by applying the right-hand brake. To swing to the left, the right-hand secondary gear was engaged, the left-hand being placed in “neutral,” the differential locked and the left-hand brake applied.

From the secondary gear-box a Coventry chain transmitted the power to an assembly, at the rear of the hull, which carried, on either side of the chain sprocket, two heavy pinion wheels, in constant mesh with the final sprocket wheels, which in turn, engaging with the links of the track plates, drove the hull along the track.

Each track was composed, normally, of ninety plates or road shoes, the separate plates being coupled together by means of links (two per plate) and link pins, the links themselves being recessed so as to engage with the driving wheels as shown above

.

The weight of the machine was carried upon the track by means of rollers, whilst the track was supported on the top of the hull by skids or rails.

Adjustment of track was effected by the movement of an “idler” wheel, which guided the track over the nose of the hull.

Refinements to the transmission were introduced in the shape of guards to protect the driving chains from mud, and also means were provided to lubricate the secondary gear-wheels with oil. It is recalled that, prior to the introduction of the chain-guard, the inside deck of the tanks was often covered with a layer of liquid mud, several inches deep, carried in by the chains, and delivered through the secondary gears.

Petrol was supplied to the engine in the earlier days of the Mark IV machine by a pressure-fed system which gave a great deal of trouble, and, being also considered dangerous, was finally discarded in favour of the Autovac system, which sucked the fuel from the main supply in a tank

outside of the machine and delivered it to the carburettor by gravity.

Cooling of the engine was primarily effected by a copper envelope radiator, which gave some trouble and was finally superseded by a tubular type.

An efficient silencer, with a long exhaust pipe carried right to the rear of the machine, considerably reduced engine noise and rendered the approach march a far less hazardous undertaking than was the case with the earlier models.

Sponsons were designed to collapse into the interior of the machine when necessary, and the cumbersome practice of detaching them from the hull came to an end. Short 6-pounder guns were introduced to render this change possible.

Detachable “spuds,” to provide a grip for the tracks on difficult soil, were first introduced for this machine, as also was a highly efficient unditching gear. The latter consisted of a beam, rather longer than the overall width of the tank hull, which was fastened by clips and chains to each track, and, in

passing round under the machine, actually took a purchase from the obstruction under the belly of the tank.

Detail improvements to give easier entrance and more rapid egress in case of emergency, as well as better and safer vision and fire control, were also introduced.

THE MARK V TANK (Plate V—see p. 204)

With the introduction of the Mark V tank, which represents the standard British heavy tank of to-day, great progress was made in all-round speed, ease of manoeuvre, radius of action, simplicity of control and feasibility of observation.

The dimensions and weight of this tank were approximately the same as those of the Mark IV, whilst the design of the hull still closely followed the lines of the original Mark I. Equipped with the 150 h.p. Ricardo 6-cylinder poppet-valved engine, specially designed for tank work, the advent of the Mark V machine called for the introduction of new courses of instruction for the personnel of the

Corps, very few of either officers or other ranks having, at this time, any experience of the care and adjustment of the valve gear.

This Ricardo engine, of somewhat unorthodox design, was highly efficient and, with proper care and attention, gave very little trouble. From the engine, power was transmitted through a plate clutch in the flywheel to a four-speed gear-box, immediately in rear of which was the reverse gear, providing “reverse” on all speeds.

The cross-shaft, incorporated with the reverse gear, carried at either end (in the same relative position as the secondary gears, explained in dealing with the Mark IV machine) an epicyclic gear. It is not within the scope of this chapter to describe this gear in detail, but it may be regarded as serving the double purpose of a reduction gear and clutch, combined in one unit.

From these epicyclic gears, the transmission of the drive through to the tracks followed the principle of the Mark IV machine, except that there was no second-line pinion assembly as in the

secondary gear of the earlier tank, the Coventry chain on the Mark V passing direct from the single-unit epicyclic gear to the pinion assembly operating the track driving wheels.

All the items enumerated above were under the direct control of the driver, who was therefore enabled to perform, single-handed, all

the operations which previously required the work of four men. Hand levers controlled the epicyclic gears, primary gear-box, and reverse gear, whilst the clutch and gear were foot-operated.

To steer the tank at any speed, the driver had merely to raise the epicyclic gear lever on the side on which he wished to turn. This had the effect of interrupting the drive to that track, so that, being driven by the remaining track, the machine would turn upon the “idle” side.

Where a sharp “swing” was necessary, application of the foot brake would automatically check the “idle” track, this being allowed for by means of a single compensating link motion with which the controls were interconnected

.

The engine was petrol-fed by the autovac system, as fitted to the later Mark IV machines. Cooling of the engine was effected by means of a tubular type radiator, the water therein being itself cooled by air drawn from outside the tank, through louvres in the left-hand wall of the hull, and finally expelled through similar louvres in the right-hand wall.

Further, the engine was completely enclosed in a sheet-iron casing, from which the hot foul air was exhausted through the roof of the tank by means of a Keith fan.

The Mark V armament corresponded with that of the Mark IV, whilst the sponsons were of similar design to those fitted to the latter type.

The absence of the large differential gear, as fitted on the earlier models, gave accommodation for a machine-gun in the rear wall of the tank, and also allowed for large entrance doors in the back portion of the roof.

A greatly improved type of rear cab was fitted, and thus provided excellent all-round vision, and

also rendered possible the fitting of the unditching beam to the tracks from the inside of the machine. This was accomplished through the side flaps of the rear cab of the Mark V, whereas on previous models it had been necessary for members of the crew to expose themselves to hostile fire, in the event of the tank becoming ditched in action, as the beam could only be attached and detached from outside.

THE MARK V ONE STAR TANK (Plate VII—see p. 220)

The Mark V star machine was 6 ft. longer than the Mark V, and the weight of the male, equipped, was approximately 33 tons. There was no change in the nature of the armament, or in the number of the crew, which consisted of eight all

told. In addition to the crew, the machine was capable of carrying twenty to twenty-five other troops and would cross a 14 ft. trench, as against 10 ft. for the Mark V.

The general mechanical arrangement of this tank corresponded with that of the Mark V, the same engine and transmission system being adopted, with the addition of a Cardan shaft between the flywheel and gear-box, which was rendered necessary by the additional length of the machine.

The Mark V star was relatively slow to manoeuvre, owing chiefly to the amount of track-bearing surface on the ground.

THE MEDIUM MARK A OR “WHIPPET” TANK (Plate III—see p. 176)

The Medium A tank, known also as the “Chaser” and “Whippet,” was the British standard light-type machine, and it differed altogether from its heavier relatives. Its weight, equipped, was about 14 tons, whilst it was 20 ft. long, 9 ft. high,

and 8 ft. 7 in. wide, carrying a crew of three. It could attain a maximum speed of about 8.3 m.p.h., and could span a trench approximately 7 ft. in width.

On this machine the tracks were not carried “overhead” as in the case of the heavy tanks, but the two trackways existed as such only, and formed the road members of what may be described as the chassis upon which the engine-room and fighting cab were mounted. There were no sponsons, and the tank was driven and fought from the cab at the rear of the machine, provision being allowed for an armament of three machine-guns.

Each machine was fitted with two 45 h.p. 4-cylinder Tylor engines with an autovac petrol feed, and cooled by means of a tubular radiator provided with two fans driven by chains from each crankshaft.

The power of each engine was transmitted through separate cone clutches, leather flexible couplings, and four-speed and reverse gear-boxes,

to a casing, at the rear of the machine, containing two worm gears.

The two worm-wheel shafts of these gears were in line, with their inner ends nearly touching, and each carrying the keyed-on half of a jawed coupling, one of which could be slid along at will, to engage with the other, thus locking the two shafts together.

One of the shafts carried a friction-clutch arrangement, designed to limit the power transmitted from one shaft to the other to about 12 h.p.

It will be seen, therefore, that either worm-wheel shaft could be driven independently by its own engine, or the two could be locked together so as to rotate at the same speed, driving the tank straight ahead, provided that there was not more than 12 h.p. difference between the developed powers of the engines. Extensions of each worm shaft carried a band brake, as well as a fan for forcing air into the cab of the machine

.

Returning to the details of the transmission system, each cross-shaft from the worm case terminated in a “driving chain pinion shaft,” the outer ends of which were supported by ball bearings mounted upon the sides of the track frames. The chain pinion carried by this shaft transmitted the drive, through a roller chain, to the final track-driving wheels, which, engaging with the slots in the track links, drove the tank along the track. Each track consisted normally of sixty-seven plates or shoes, and rollers served to support the weight of the tank upon the track, as well as to carry the track over the top of the trackway. Adjustment of the track was effected by movement of the front “idler” wheel as in the case of the heavier machines.

The Whippet tank called for particular skill in driving, and a great deal of practice was usually necessary to produce a really efficient driver. “Stalling” of one or both engines was a common occurrence during the earlier stages of training. Steering was effected by varying the speed of either

engine, and the radius of movement was proportional to the difference in the speed of the two engines, this difference being controlled by means of a steering wheel connected to the two carburettor throttles, movement of the wheel producing acceleration of one engine and deceleration of the other simultaneously.

THE GUN-CARRYING TANK (Plate VII—see p. 220)

Originally designed for carrying a 60-pounder gun or 6-in. howitzer and ammunition into action, these machines during 1918 were chiefly used for the transport of supplies across country. The engine, a 6-cylinder 105 h.p. Daimler, was placed right at the rear of the machine, and the general lay-out of the transmission corresponded with that of the Mark IV modified to suit the engine. position, the primary and secondary gears, etc., being mounted forward of the engine in the case of this G.C. tank. The final drive to the track was at the rear, and exactly followed the Mark IV practice, whilst the track itself was carried on track frames,

in this respect somewhat resembling the Medium A machine.

Four men were required to control the G.C. tank, the driver and brakesman being separately housed in two small independent cabs mounted one over each track towards the front of the machine, whilst the secondary gearsmen travelled in the body of the machine.

A system of signalling by signs from driver to other members of the crew was adopted.

Situated between the inner walls of the hull at the front of the tank was a “skid” or platform which could be drawn out, and its front lowered to the ground, forming an inclined runway up which the gun was hauled, by means of a winding gear operated from the engine, to its travelling position on the machine.

Drums for carrying ammunition for the guns were supported on platforms over the tracks immediately in rear of the two control cabs

.

The first G.C. tanks were fitted with “tails,” similar to those on the Mark I machines, but these were later on discarded.

The above includes the brief mechanical summary of the various types of British tanks used during the Great War, and though, undoubtedly, the future will bring with it many improvements and may radically change the whole form of the present-day tank, it is doubted if ever, in the whole history of mechanics—let alone warfare, a novel machine has been produced which has proved so efficient on first use and required in the long run of two years of war so few changes.