CHAPTER VIII — TANK TACTICS

THE training of the Heavy Branch having been laid down, it was next necessary to discover and decide upon a common method of tactics,’ so that directly individual instruction had been completed collective training might be based on it; further, rumours were already afloat that the Heavy Branch might be called upon to take part in the spring offensive, so there was no time to be lost in deciding upon suitable methods and formations of attack. This was done early in February, when “Training Note No. 16,” which will long be remembered by many in the Tank Corps, was issued.

Though experience is the only true test of a system of tactics, the foundations of the tactics suitable to any particular weapon are not based on experiences, but on the limitations of the weapon, that is on its powers, and on the fundamental principles of war. Further than this, if the weapon

concerned is to be employed in co-operation with other weapons, the powers of these other weapons must also be considered, so that all the weapons to be employed may, so to speak, like a puzzle, be fitted together during battle to form one united picture.

In thinking out a tactics for tanks, the first factors to bear in mind are the powers of the machine, which may be summarised in three words: “penetration with security.” Heretofore fronts had remained to all intents and purposes inviolable to direct infantry attacks; the tank was now going to break down this deadlock through its ability to cross wire and trenches under fire with far less risk than infantry could ever hope for. Mechanically, the machine

At this time, January 1917, General Swinton’s notes given in Chapter IV were not known of at the Heavy Branch Headquarters. was far from perfect, consequently, it was laid down, as a general rule, that never fewer than two tanks should operate together, and when possible not fewer than four.

From a military point of view the penetration of a line of defence does not simply mean passing straight through it, but cutting it in half, and then

by moving outwards as well as forwards to push back and envelop the flanks thus created and so widen the base of operation to admit the movement forwards of reserves and supplies, and the movement backwards of casualties and tired troops. A man getting through a hedge first selects a weak spot (point of attack), he then forces his arms through the branches (penetration), and pushing them outwards (envelopment), forms a sufficiently large gap (base of operations) to permit of his body (army) passing easily through the hedge (enemy’s defences).

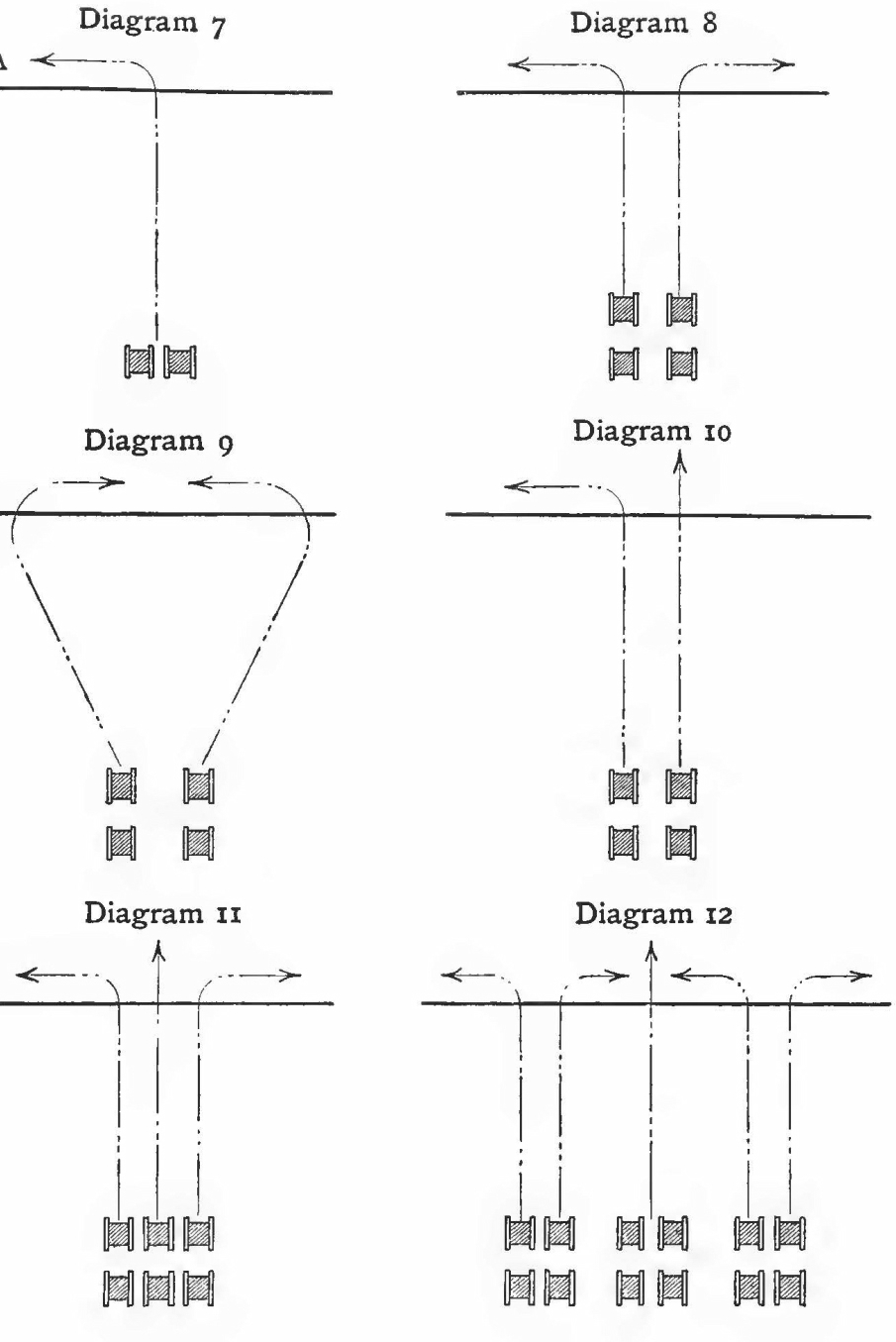

The operation of penetration with tanks is just the same. Take a half section, two machines; this half section first penetrates the enemy’s defences by crossing them (see diagram 7), then by moving outwards, say to the left, starts enlarging the base by driving the enemy towards A, and so makes a gap between the point of penetration and A, for the infantry to move through. As the enemy may, whilst the tanks are working towards A, seek refuge in his dugouts and “come to life” again after

the tanks have passed by, it is necessary that the tanks should be followed by an infantry “mopping up” party which will bomb the dugouts and so render “coming to life” less frequent. As the bombing party has to work up the trench with the tank, it cannot hold the trench once it is cleared, consequently another party of infantry should follow the bombers, whose duty it is to garrison the trench on it being captured. We therefore find that even in the smallest tank attack two parties of infantry are required: in trench warfare these are known as “moppers up” and “support,” and in field warfare as “firing line” and “supports.” Frequently it is as well to add another party, a “reserve,” so that some definite force of men may be held in hand to meet any unexpected event.

If instead of two tanks we use four, a much more effective operation may be carried out. The tanks can either penetrate at one place, and wheel

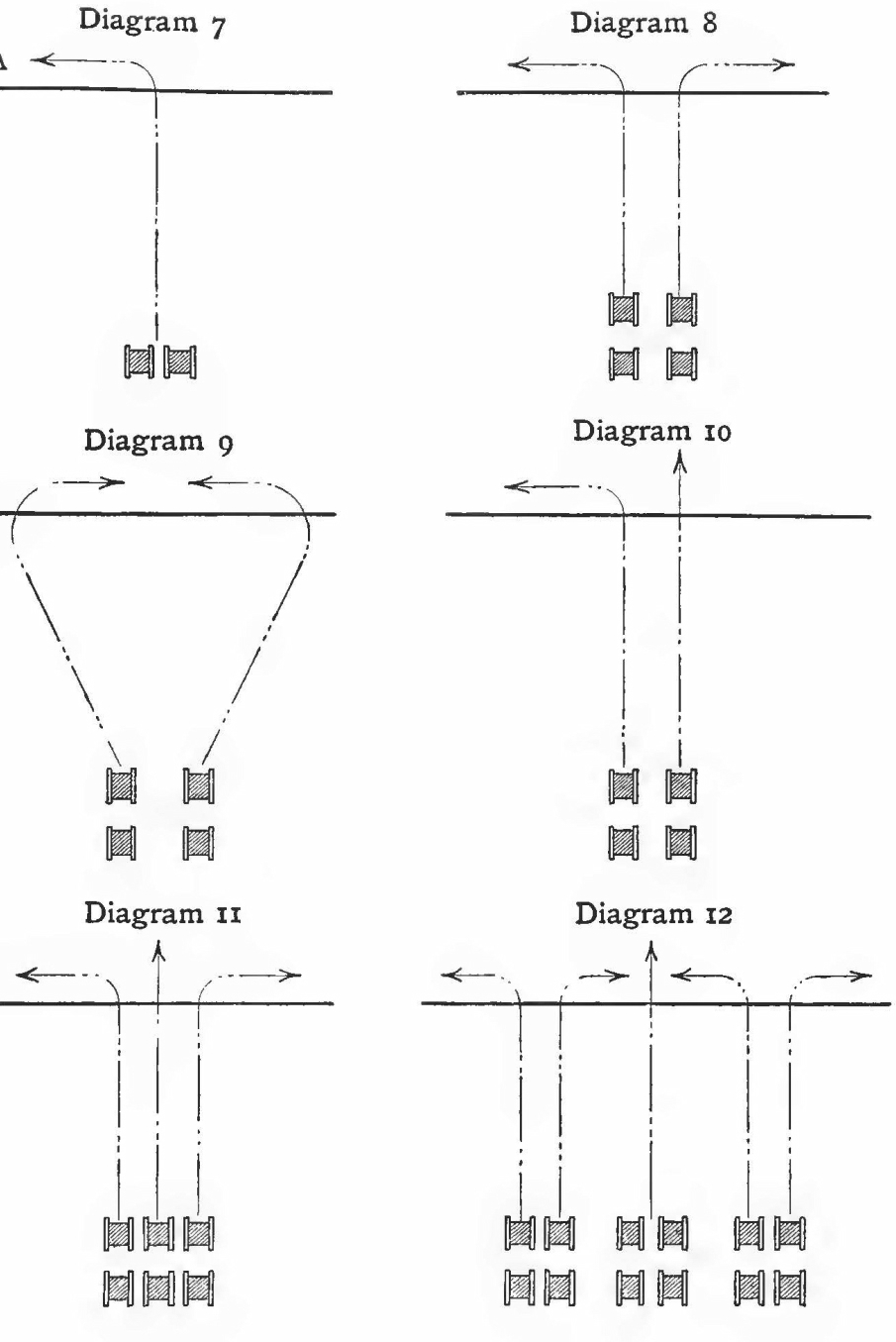

outwards by pairs (see diagram 8), or by pairs penetrate at two separate points and wheel inwards, pinching on the centre (see diagram 9), or two can wheel to a flank and two proceed straight ahead (see diagram 10) and threaten the enemy’s line of retreat. When this latter operation is contemplated it is as well to make use of at least six machines, better twelve, i.e.

a complete company of tanks. If six machines are used they normally should strike the enemy’s line at approximately the same place; from there one half section should go straight forward and one to each flank, forming what has been called the “Trident formation” (see diagram 11). If twelve machines are employed, then each section of four tanks strikes the trench at a separate point, the centre section forging straight ahead and the flanking sections moving inwards and outwards as depicted in diagram 12.

Particular attention should be paid to the outward movements of the flanks, for, as the flanks of our own penetrating or attacking force are

generally the most vulnerable points, if we can push forward offensive wings on these flanks we shall not only be protecting our own flanks from attack, by giving the enemy no time to attack in, but we shall be protecting our central line of advance as well. The force operating along this central line not only depends for its movement forward on the security of its flanks, but also on the size of the base of operations; the broader this base the more secure will it be, for the one thing an attacking army wishes to avoid is getting into a pocket on the interior of which all hostile fire is concentrated

.

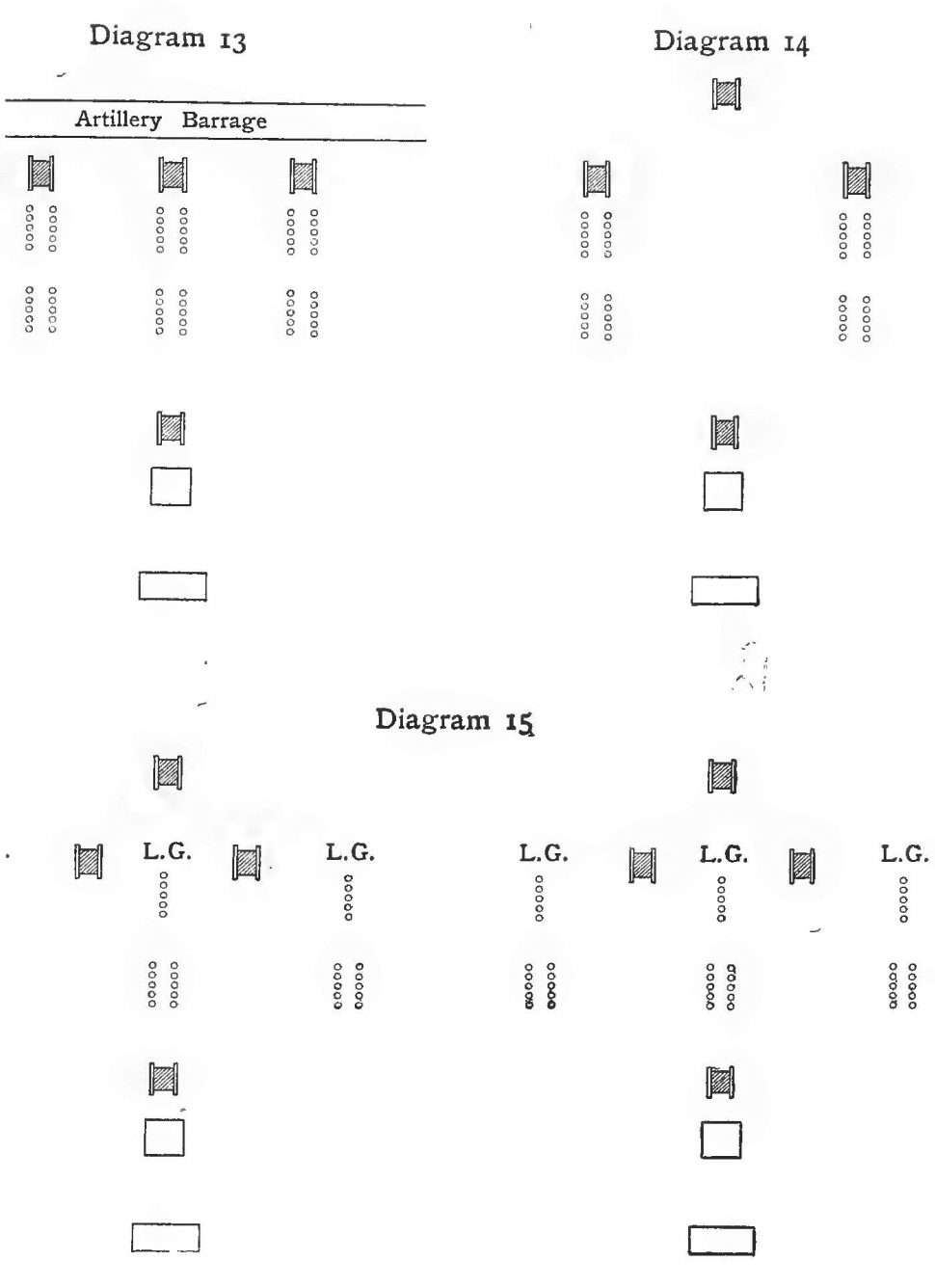

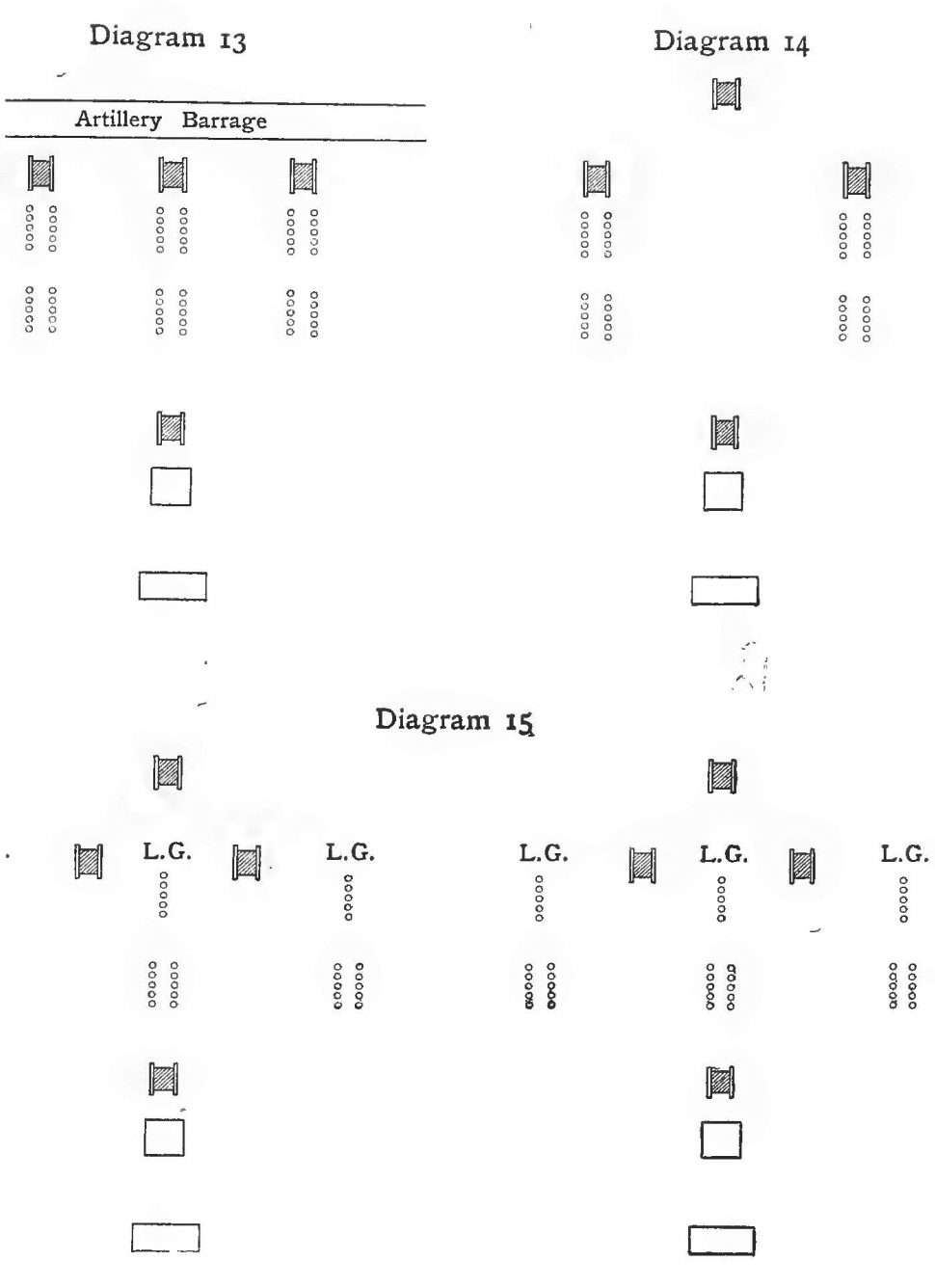

From the above elementary movements can be worked out a whole series of battle formations according to the various arms which are to be employed. The following three were those generally used by tanks from the battle of Cambrai onwards:

(1)

An attack against trenches with an artillery barrage

(see diagram 13).—Three tanks in line at 100 to 200 yards’ interval, followed by infantry in sections, each section forming an independent fighting unit advancing in single file and attacking in line, the whole forming one firing line. Behind this firing line should advance one tank and a certain number of infantry sections as a support. Reserves can be added as necessary.

(2)

An attack against trenches without an artillery barrage

(see diagram 14).—One tank in advance, followed at a distance of 100 to 150 yards by two others at 200 to 300 yards’ interval, and one tank in support. The infantry should be disposed of as before. The advanced tank to a certain extent replaces the artillery barrage and acts as a scout to the two behind, which form part of the infantry firing line.

(3)

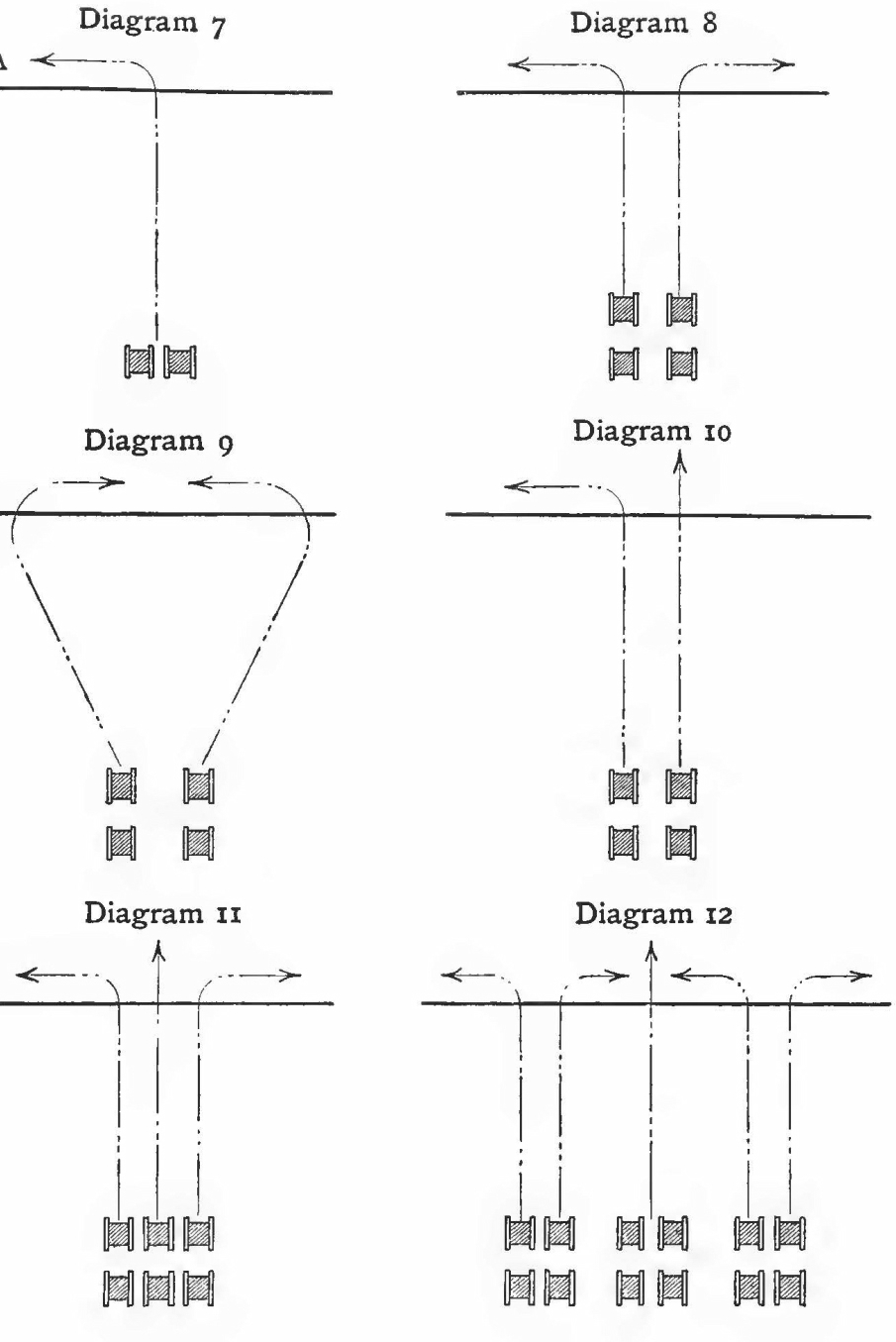

The field warfare attack

(see diagram 15).—In the field attack the action of the tanks must be adapted to circumstances. This action falls under three headings:

-

Moving in front of the infantry firing line.

-

Moving with the infantry firing line.

-

Moving behind the infantry firing line.

When moving with the infantry firing line, which will generally be the most suitable formation to adopt, tank sections should form mobile strong points or bastions, which will not only reduce the number of infantry required for the firing line, but which will be able to bring oblique and cross fire to bear in front of the advancing infantry. In order to reduce the human target as much as possible without reducing fire effect, Lewis-gun sections should freely be used to cover by fire the intervals between tank sections. These Lewis-gun sections should be followed by rifle sections which, directly opposition is broken down by the tanks and the Lewis gunners, should move rapidly forward several hundred yards in front of the tank and infantry firing line, forming to it a protective screen of sharp shooters. This formation should then be maintained until the rifle sections get hung up, when the tank and Lewis-gun firing line should

pass through them to renew the attack, the rifle sections forming up in support in rear. Curiously enough this formation resembles very closely that generally adopted by the Roman Velites and Hastati (riflemen), Principes (Lewis gunners), Triarii (tanks), and Napoleon’s Light Infantry (riflemen), Infantry of the Line (Lewis gunners), Old Guard and Heavy Cavalry (tanks).

As an infantry attack depends on the following principles —the objective, the offensive, security, mass, economy of force, surprise, movement, and co-operation—so does a tank attack. The tank must know what it is after, it must act vigorously, it must be protected by artillery just like infantry, it must attack in mass, that is in strength and numbers, but not, necessarily, all in one place; it must surprise the enemy, move as rapidly as it can, and work hand in glove with the other arms. On the application of these principles to the conditions which will be met with will depend the success or failure of the tank attack

.

The first condition to inquire into is the position of the objective; is the ground leading up to it suitable for tank movement, is the country on the flank of such a nature as to permit of offensive wings being. formed? The second is the position and number of the enemy’s guns; can these be controlled by counter-battery work or smoke; how will they affect the lines of approach and their selection? The third is the number of subsidiary objectives before the final one is captured. The fourth is the “springing off” position of our own infantry, and the fifth is, how can the enemy be surprised? These five questions being satisfactorily answered, the normal procedure is to divide the whole tank force into a main body and two wings; to take these three forces and to divide each up into as many lines of tanks as there are objectives to be attacked; to divide each objective up into tank attack areas according to the number of tactical points each contains. Provided the enemy does not possess tanks himself, or a sure antidote to their use, which the Germans never did possess, a well-

considered and mounted tank, infantry, artillery, and aeroplane attack is the nearest approach to certainty of success

that has ever been devised in the history of war. No well-planned extensive tank attack has in the past ever failed, and each one has resulted in more prisoners having been captured than casualties suffered. These are historic facts and not mere pans of praise; they, consequently, deserve our most careful consideration when eventually we plan and prepare for the future.