CHAPTER IX — THE BATTLE OF ARRAS

THE great battles which opened the Allies’ 1917 campaign on the Western Front were the direct outcome of two main causes:

(1) The strategical positions of the opposing Armies resulting from the battle of the Aisne in 1914.

(2) The tactical position of the same Armies resulting from the battle of the Somme in 1916.

The former placed nine-tenths of the German Army in the west, in a huge salient Ostend-Noyon-Nancy; the latter a considerable portion of that Army in a smaller one, Arras-Gommecourt-Morval. The former offered possibilities for the Allies to get in a right and left hand blow on two of the main centres of the German communications—Valenciennes and Mézières; the latter a right and left hand blow in the direction of Queant against

the northern and southern flanks of the German Sixth and First Armies.

Had it been possible to bring off these latter blows successfully, such a debacle of the German forces would have resulted that not only would the advance of the British First, Third, Fourth, and Fifth Armies have seriously threatened Valenciennes, but the rush of German reserves to stop the gap would have withdrawn pressure from before the French about Reims, and would probably have enabled them to advance on Mézières.

A plan for an attack in the vicinity of Arras had been considered shortly before the opening of the battle of the Somme on July 1, 1916; it was then dropped, only to be revived in October, when the plan contemplated was to drive in the northern flank of the Gommecourt salient. It was hoped to employ two battalions of forty-eight tanks each in this operation; but, as the tanks promised in January did not materialise until the end of April, this plan bad to be continually modified

.

Meanwhile a hostile operation began to take place which bid fair to filch from us the tactical advantage we had won during the preceding summer. Towards the end of February it became apparent that the Germans intended to evacuate the Gommecourt salient; and the recent construction of the Hindenburg Line suggested a rounding off of the right angle between Arras and Craonne.

The German retirement necessitated certain changes in the British plan of operations. The Fourth Army relieved the French between the Somme and Roye; the Third Army, consisting of five Corps and three Cavalry Divisions, was now to penetrate the German defences, and by marching on Cambrai turn the Hindenburg Line from Heninel to Marcoing; the First and Fifth Armies were to operate on the left and right flanks of the Third Army.

The success of the British plan of attack depended on penetrating not only the German front-line system, but also the Drocourt-Queant

line within forty-eight hours of initiating the attack; for, by so doing, so severe a wound would be inflicted that the Germans would be forced to move their reserves towards Cambrai and Douai, and away from Soissons and Reims, where the main blow was eventually to fall. Time, therefore, was, as usual, the all-important factor—could the Drocourt-Queant line be penetrated before the enemy was able to assemble his reserves?

Tanks, it was decided, should assist in gaining this time, yet on April 1, after denuding the training grounds of both England and France, only 60 Mark I and Mark II tanks could be reckoned on for the battle.

There were three ways in which these sixty tanks could be used, either by concentrating the whole against one objective such as Monchy-le-Preux, if a penetration of the centre were required, or against Bullecourt, if an envelopment of the German left flank were considered necessary, or to allot a proportion of machines to each Army or Corps for minor “mopping up” operations

.

The last-mentioned course was eventually adopted and the following allotment of machines made:

- Eight tanks, to the First Army to operate against the Vimy Heights and the village of Thelus.

- Forty tanks to the Third Army, eight to operate with the XVIIth Corps north of the river Scarpe, and thirty-two to operate with the VIth and VIIth Corps south of the river Scarpe.

- Twelve tanks to operate with the Fifth Army.

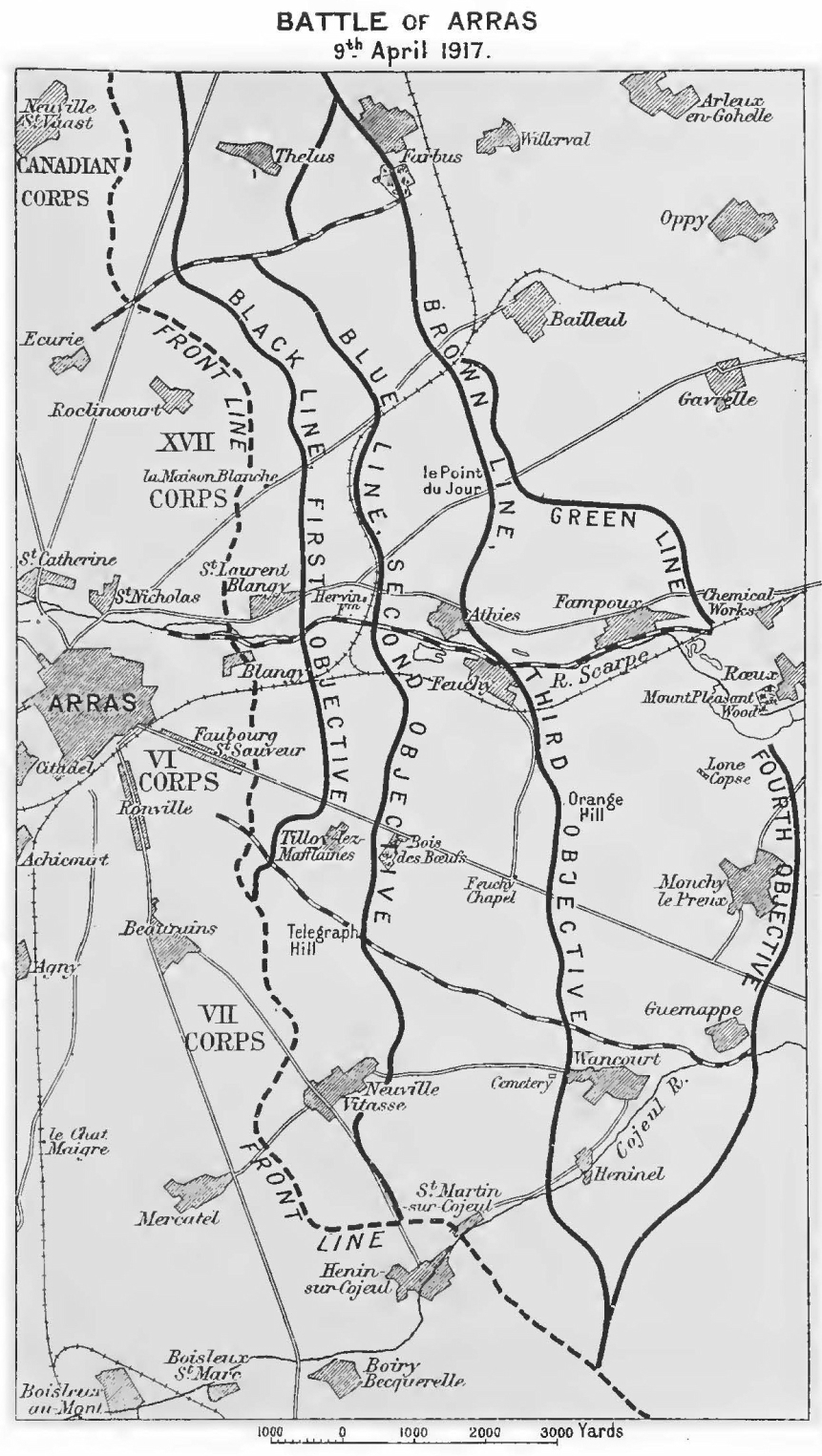

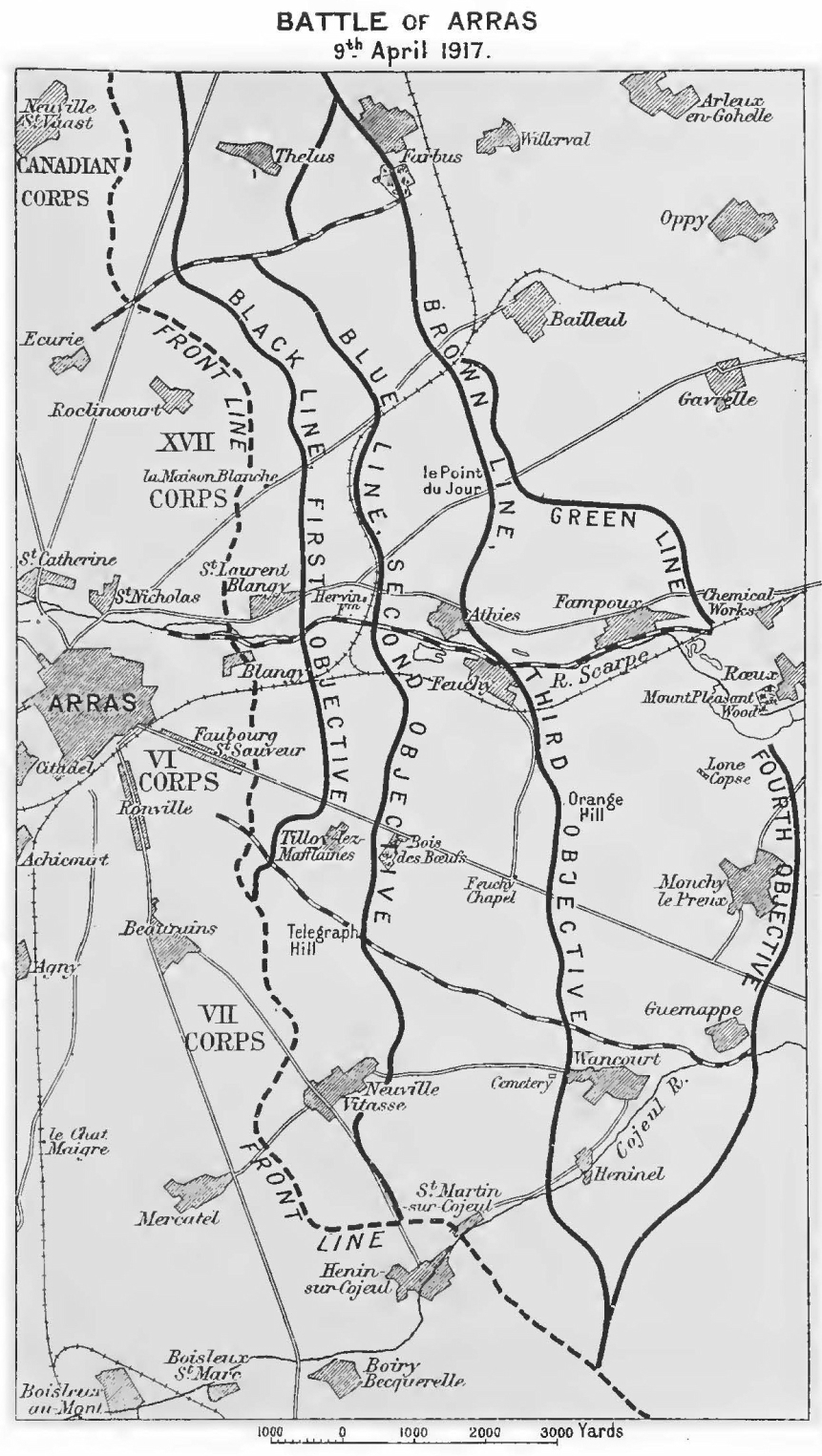

The Third Army plan of operations was as follows: The VIth and VIIth Corps were to attack south of the river Scarpe between Arras and Mercatel. Their objective ran from a point 2,000 yards south-east of Henin-sur-Cojeul northwards to Guemappe, thence east of Monchy-le-Preux to the Scarpe. This objective was 10,000 yards in length and 8,000 in depth. It contained two formidable lines of defences:

- The Cojeul-Neuville Vitasse-Telegraph hill-Harp-Tilloy les Mafflaines line, much of which had been fortified for over two years.

- The Feuchy Chapel-Feuchy line.

South of these systems was the Hindenburg Line, and east of them Monchy-le-Preux, which dominates the whole of the surrounding country. Three valleys lie between this eminence and the city of Arras.

The XVIIth Corps was to continue the attack north of the river Scarpe and occupy a line running from east of Fampoux to the Point du Jour, and thence to a point 4,000 yards east of Roclincourt. The country along the northern bank of the Scarpe was intricate, and in it many excellent positions existed for hostile machine-guns. Further, the railway running to Bailleul was in itself a formidable obstacle.

The First Army attack comprised the taking of the famous Vimy Heights, Thelus and the hill north of Thelus, a position considered one of the strongest in France

.

The Fifth Army was to operate between Lagnicourt and the right of the Third Army, driving northwards towards Vis-en-Artois. The operation to be carried out by this Army was a most difficult one. The destruction of the roads and the bad weather had rendered it impossible to move forward sufficient artillery—a sine qua non

of all attacks of this period.

The whole of the above operations were to be considered as the preliminaries to the advance of two Cavalry Divisions and the XVIIIth Corps south of the Scarpe, which force was to break through at Monchy and advance eastwards on to the Drocourt-Queant line.

The general preparations required for a tank battle will be dealt with in another chapter, suffice it here to state that they were divided up as follows—preliminary reconnaissances, the formation of forward supply dumps, the preparation of tankodromes and places of assembly, the programme of rail movements and the fixing

and preparing of the tank routes forward from the tankodromes.

Reconnaissances were started as early as January, and were most thoroughly carried out. Supply dumps were formed at Beaurains, Achicourt, near Roclincourt and Neuville St. Vaast. As no supply tanks were in existence, supplies had to be carried forward by hand and, at the time, it was reckoned that had these machines been forthcoming, each one would have saved a carrying party of from 300 to 400 men. The railheads for the Fifth, Third, and First Armies were selected at Achiet le Grand, Montenescourt, and Acq respectively. The movements of tanks and supplies to these stations were successfully carried out after several minor hitches, such as trucks giving way, trains running late, and, on March 22, 20,000 gallons of petrol being destroyed in a railway accident. Incidents such as these are, however, of little account if the plan has been worked out with foresight

.

The only real mishap which occurred took place on the night of April 8-9, to a column of tanks which was moving up from Achicourt to the starting-points. Achicourt lies in a valley through which runs the Crinchon stream. The surface of the ground here is hard, but under this superficial crust lies, in places, boggy soil which was only discovered when six tanks broke through the top strata and floundered in a morass of mud and water. Those who were present will never forget the hours which followed this mishap. Eventually the tanks were got out, but too late to take part in the initial attack on the following day

.

On April 7 and 8 the weather was fine, but, as ill-luck would have it, heavy rain fell during the early morning of the 9th. At zero hour (dawn) the tanks moved off behind the infantry, but the heavily “trumped” area on the Vimy Ridge, soaked by rain as it now was, proved too much for the tanks of the First Army, and all became ditched at a point 500 yards east of the German front line, and never took part in any actual fighting. The four which started from Roclincourt had but little better luck, and though they advanced considerably further they also ditched and went out of action.

The artillery barrage was magnificent and the Canadians went forward under it and took the Vimy Heights almost at a rush, capturing several thousand prisoners. The rapidity of this advance, due to the excellent work of our artillery and the dash of the Canadians, rendered the cooperation of tanks needless; it was, therefore, decided to withdraw the eight machines with the First Army, and send them to the Fifth Army. Those from

Roclincourt were also withdrawn to reinforce those operating immediately north of the Scarpe.

The four tanks which started just east of Arras had better luck, for though one was knocked out by shell fire shortly after starting, the remaining three worked eastwards down the Scarpe and rendered valuable assistance to the infantry by “mopping up” hostile machine-guns.

South of the Scarpe the infantry attacked with equal élan. About Tilloy les Mafflaines, the Harp, and Telegraph hill the tanks caught up with the attack and accounted for a good many Germans, and then, pushing on, helped in the reduction of the Blue line (Neuville Vitasse-Bois des Bœufs-Hervin farm) and such parts of the Brown (Heninel-Feuchy Chapel-Feuchy) as they were able to reach during daylight.

The ground on the Harp, an immensely strong earthwork, was much “trumped” and some of the trenches had 2 ft. of water in them. A good many tanks bellied here.

The operations of the tanks on the 9th can only be considered as partially successful—due chiefly to

the difficulty of the ground, wet and heavily shelled, and the rapidity of the infantry advance.

On the following day only minor operations were undertaken, and salvage was at once started, the ditched tanks being dug out and withdrawn to refit.

On the 11th three important tank attacks were made, the first from Feuchy Chapel on Monchy; the second from Neuville Vitasse down the Hindenburg Line, and the third against the village of Bullecourt.

The first attack was eminently successful for, though only three of the six tanks which started from Feuchy Chapel reached Monchy, it was due to the gallant way in which they were fought more than to any other cause that the infantry were able to occupy this extremely valuable tactical position. Once Monchy was captured the cavalry moved forward. From all accounts the Germans, at this period of the battle, were in a high state of demoralisation, but notwithstanding this, as long as they possessed a few stout-hearted machine-gunners, an effective cavalry advance was

impossible, and the only arm which could have rendered its employment feasible was the tank—the machine-gun destroyer—and as there were no longer any fit or capable of coming into action the Germans found time to stiffen their defence and to consolidate their position.

The second attack was made from Neuville Vitasse with four tanks. These machines worked right down the Hindenburg Line to Heninel, driving the Germans underground and killing great numbers of them. They then turned north-east towards Wancourt, and for several hours engaged the Germans in the vicinity of this village. All four eventually got back to our lines after having fought a single-handed action for between eight and nine hours. It was a memorable little action in spite of the fact that its ultimate value was not great.

The third operation, the attack on and cast of the village of Bullecourt, is the most interesting of the three. All previous operations in this battle had been based on the timing and strength of the artillery barrage, the tanks taking a purely

subordinate part. In the present attack the position of the tanks, as compared with the other arms, was reversed; for they took the leading part, and though the attack was eventually a failure, they demonstrated clearly the possibility of tanks carrying out duties which up to the present had been definitely allotted to artillery —the two chief ones being wire-cutting and the creeping barrage which, henceforth, could be carried out by wire-crushing and the mobile barrage produced by the tank 6-pounders and machine-guns.

The plan of attack was as follows: 11 tanks were to be drawn up in line at 80 yards interval from each other, and at 800 yards distance from the German line. Their task was to penetrate the Hindenburg Line east of Bullecourt; 6 to wheel westwards (4 to attack Bullecourt and 2 the Hindenburg Line north-west of Bullecourt), 3 to advance on Reincourt and Hendecourt, and 2 to move eastwards down the Hindenburg trenches. This operation was similar to the one already

discussed in Chapter VIII, “Tank Tactics,” and called the “Trident Formation.”

All 11 tanks started at zero, which was fixed at 4.30 a.m. Those on the wings were rapidly put out of action by hostile artillery fire; however, 2 out of the 3, ordered to advance on Reincourt and Hendecourt, entered these villages and the infantry following successfully occupied then.

In spite of the very heavy casualties suffered, the tanks in the centre had carried out their work successfully, when a strong converging German counter-attack, partly due to the impossibility of creating offensive flanks to our central attack, retook the villages of Reincourt and Hendecourt, captured the two tanks and several hundred men of the 4th Australian Division. The loss of the two tanks was unfortunate, for the Germans discovered that their latest armour-piercing bullets would penetrate their sides and sponsons. This discovery led to a German order being published that all infantry should in future carry a certain number of these bullets

.

The interest of the Bullecourt operation lies in the fact that it was the first occasion on which tanks were used to replace artillery. It failed for various reasons—the haste with which the operation was prepared; the changes in the plan of attack on the night prior to the attack; the unavoidable lack of artillery support; and above all the insufficiency of tanks for such an operation and the lack of confidence on the part of the infantry in the tanks themselves.

Between April 12 and 22 all tank operations were of a minor nature. By the 20th of this month thirty of the original machines were refitted and on the 23rd eleven of these were employed in operations around Monchy, Gavrelle, and the Chemical Works at Rœux; excellent results were obtained, but no fewer than five out of the eleven machines sustained serious casualties from armour-piercing bullets, which had now become the backbone of the enemy’s anti-tank defence.

The general result of the tank operations was favourable, though the number of casualties

sustained exceeded expectation. The value of the work they accomplished was recognised by all the units with which they worked. The casualties they inflicted on the enemy were undoubtedly heavy; in most cases where they advanced the infantry attack succeeded, and the highest compliment which was paid to their efficiency came from the enemy himself, who took every possible step to counter their activity.

The operations showed that the training of all ranks had been carried out on sound and practical lines. The fighting spirit of the men was high, the tanks being fought with great gallantry. One commanding officer stated, in his report on the battle, that the behaviour of his officers and men might be summed up as “a triumph of moral over technical difficulties.”

This fine fighting spirit was undoubtedly due to the excellent leadership all officers and N.C.O.s had exercised during individual and collective training; and to the full recreational training given to the battalions during these periods, games and

sports as a fighting basis having been sedulously cultivated.

The main tactical lessons learnt and accentuated were that tanks should be used in mass, that is they should be concentrated and not dispersed; that a separate force of tanks should be allotted to each objective, and that a strong reserve should always be kept in hand; that sections and, if possible, companies should be kept intact; that the Mark I and Mark II machines were not suitable to use over wet heavily-shelled ground; that the moral effect of tanks was very great; that counter-battery work is essential to their security; and that supply and signal tanks are an absolute necessity.

On the evening of April 10 the Colonel Commanding the Heavy Branch received the following telegram from the Commander-in-Chief:

“My congratulations on the excellent work performed by the Heavy Branch of the Machine Gun Corps during yesterday’s operations. Please convey to those who took part my appreciation ‘of the gallantry and skill shown by them.”