CHAPTER XIII — THE BATTLE OF MESSINES

THE situation at the end of April 1917 was a difficult one for the Allies. The failure to penetrate the Drocourt-Queant line had rendered the whole plan of the British attack east of Arras abortive; this was bad enough, but indeed a minor incident when compared with the failure of the great French attack in Champagne. It was towards making good this failure that the rest of the year’s operations had to be directed.

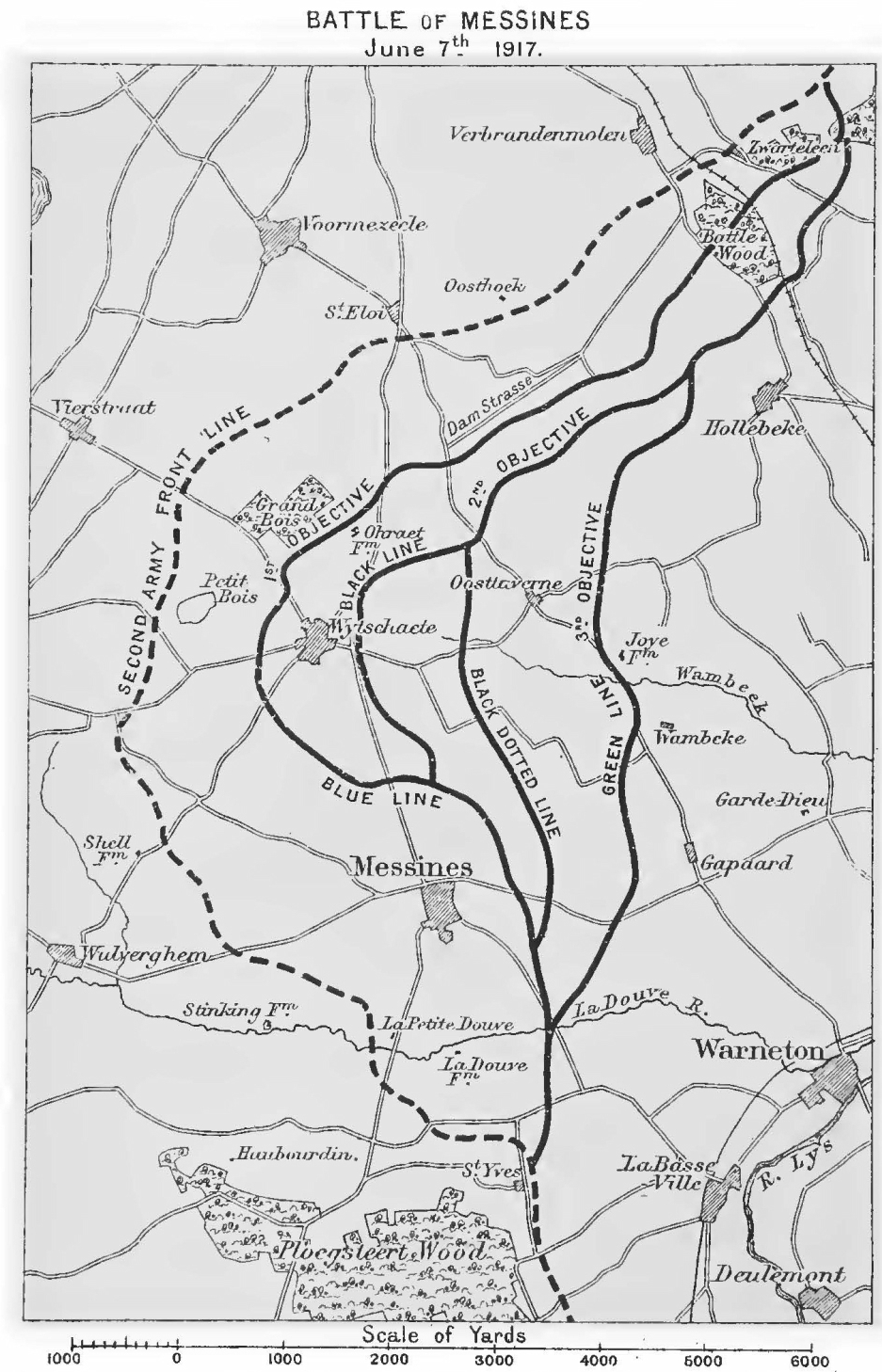

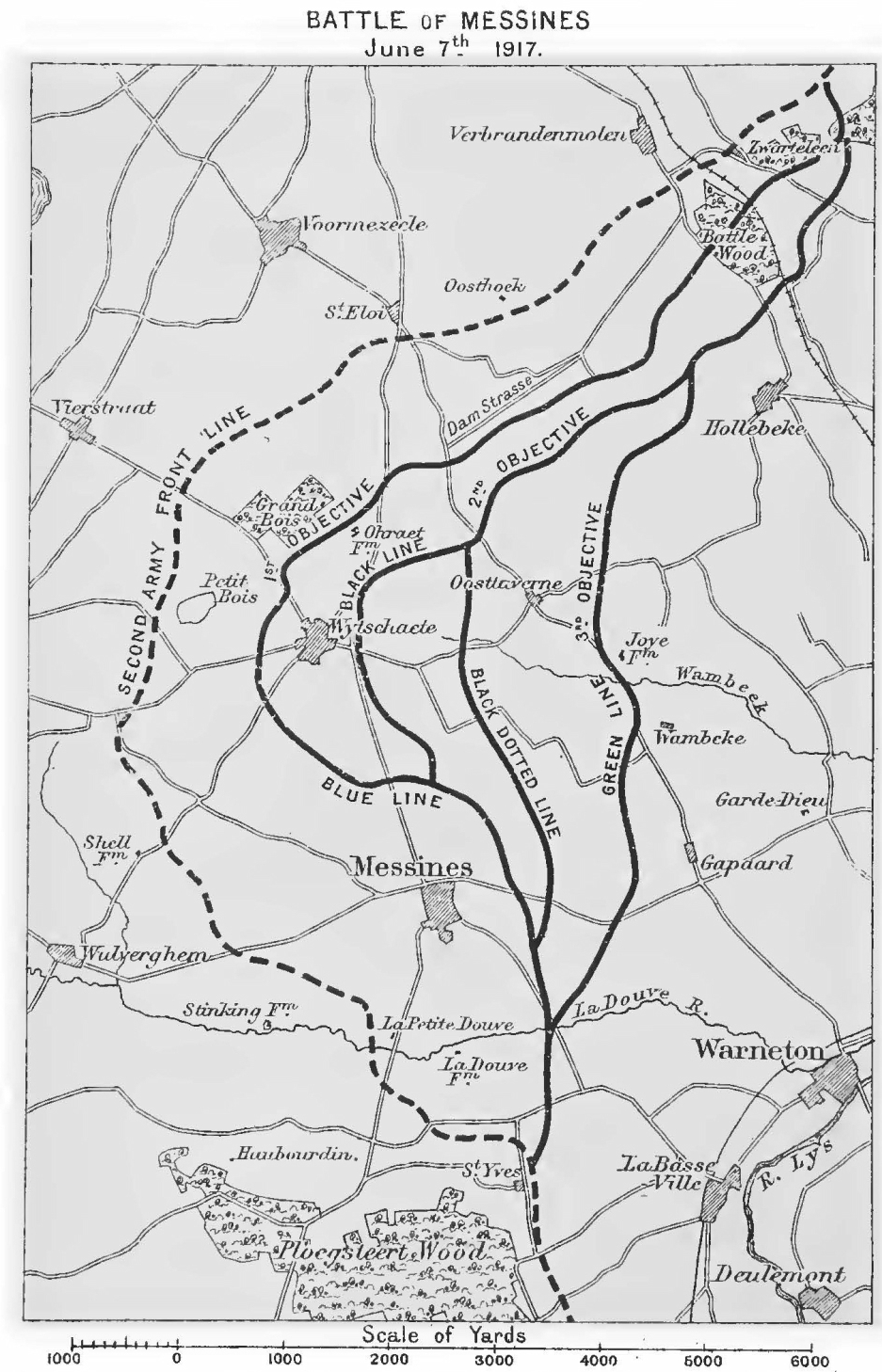

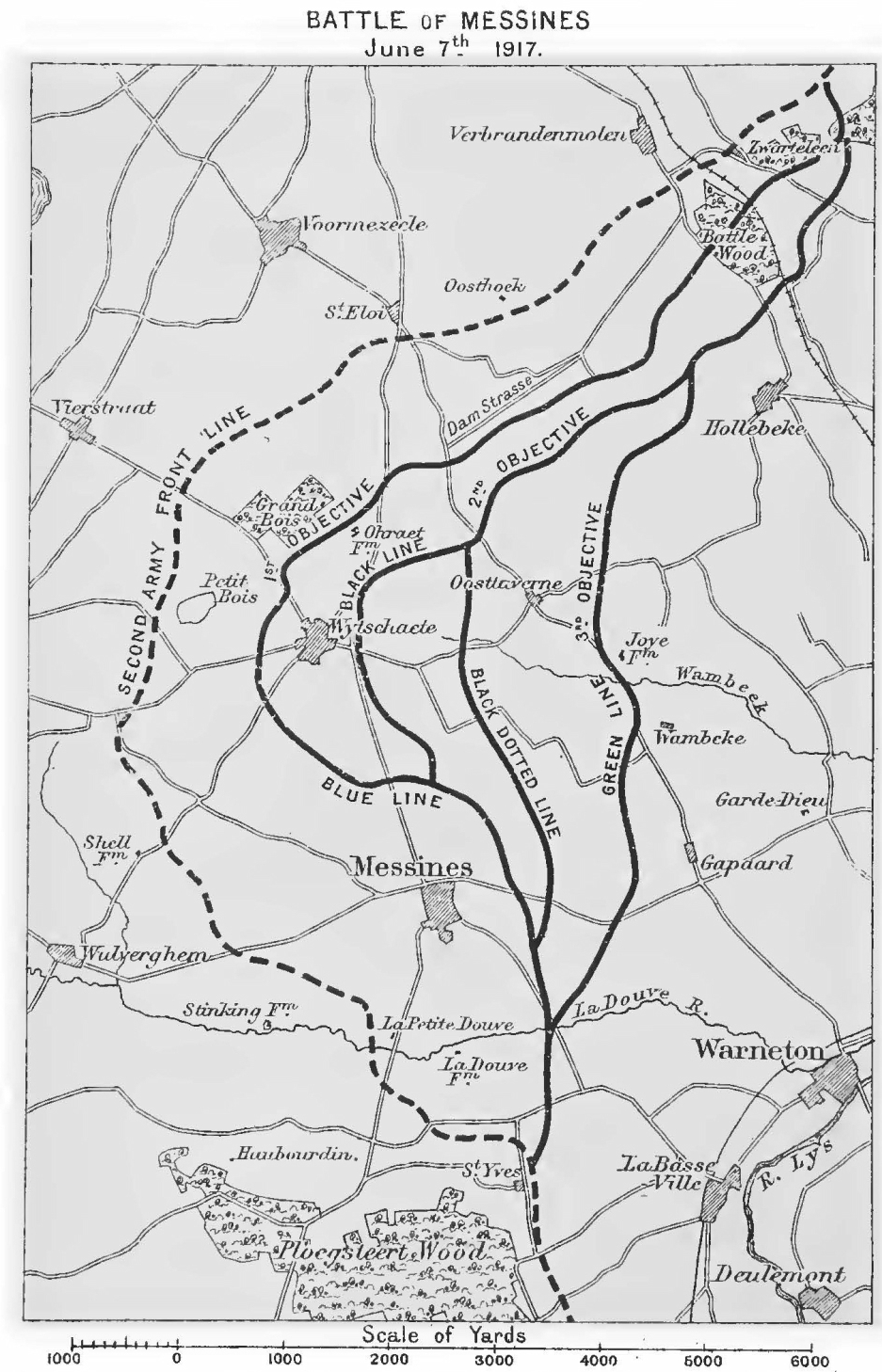

The ambitious plan of cutting off the Arras-Soissons-Reims salient having failed, the next blow was to be directed against the German right flank. The object of this attack was to drive this flank back sufficiently far to deprive the Germans of the coast line between Nieuport and the Dutch frontier, and to render their position about Lille sufficiently insecure to force them to evacuate it and so open the road to Antwerp and Brussels

.

The possibility of such an operation as this had long been contemplated, and, as early as the summer of 1916, preparations for it had been taken in hand by the British Second Army. By May 1917 these were completed, including the construction of an extensive system of railways in the Ypres area and the mining of most of the western flank of the Messines-Wytschaete ridge.

The operation was to be divided into two main phases, firstly the taking of the Messines-Wytschaete ridge so as to secure the right flank of the second phase and to deny the enemy important points of observation, and secondly the attack north of this ridge with the object of occupying the coast line and of pushing forward towards Ghent. The first phase constituted the battle of Messines, the subject of this chapter, and the second the Third Battle of Ypres.

It had been foreseen early in the year that such an attack was possible, and that in all probability tanks would be called upon to take part in it, consequently, as early as March 1917,

reconnaissances of the whole of the Ypres area had been taken in hand by the Heavy Branch. In April this surmise proved correct, and the 2nd Brigade, consisting of A and B Battalions, was selected for this operation. In May these two battalions were equipped with thirty-six Mark IV tanks each.

Railheads were selected at Ouderdom and at Clapham Junction (one mile south of Dranoutre), and though they were within the shelled area, they fulfilled most of the requirements demanded of a tank railhead. Advanced parties began arriving at these stations on May 14, and between May 23 and 27, A and B Battalions followed them. Supply dumps were then formed, and arrangements were made to carry forward one complete fill for all tanks operating by means of Supply Tanks, which were first used in this battle. These tanks consisted of discarded Mark I machines with specially made supply sponsons fitted to them.

The positions of assembly were selected quite close to railheads, B Battalion tanks being hidden away in a wood, and A Battalion’s in specially built

shelters representing huts. The spoor left by the tanks, as they moved to these positions, was obliterated by means of harrows so that no enemy’s aeroplane happening to cross over our lines this way would notice anything suspicious on the ground

.

The object of the Second Army’s operations was firstly to capture the Messines-Wytschaete ridge and secondly to capture the Oosttaverne line, a line of trenches running north and south a mile to a mile and a half east of the ridge. Three Corps were to participate in this attack—the Xth and IXth Corps, and the IInd Anzac Corps. To these Corps tanks were allotted as follows: 12 tanks to the Xth Corps, 28 tanks to the IXth Corps, 16 for the ridge, and 12 for the Oosttaverne line, and 32 tanks to the IInd Anzac Corps, 20 for the ridge and 12 for the Oosttaverne line. Each battalion had two spare tanks and 6 supply tanks. The number of tanks used was, therefore, 76 Mark IV tanks and 12 Mark I and II Supply Tanks.

The tank operations were planned to be entirely subsidiary to the infantry attack, in fact the whole attack, being limited to a very short advance, was based on the power of our artillery and the moral effect produced by exploding some twenty mines simultaneously at zero hour.

For three weeks the weather had been dry and fine, and had this not been the case, there would have been little hope of ever being able to move the tanks forward over the pulverised ground. The artillery bombardment opened on May 28, June 7 being fixed for the attack. It was a terrific cannonade, watching it from Kemmel hill or the Scherpenberg, to-day almost blasted out of recognition themselves, one could see the Grand bois, Wytschaete wood, and the green fields along the valleys of the Steenbeek and Wytschaetebeek being slowly converted into a dun-coloured area which the first heavy fall of rain would convert into a porridge of mud. Some shells as they exploded would throw up great fan-shaped masses of debris and smoke, others would burst into vortex rings, whilst others again shot up into the air great feathers of fine brown dust. Day and night the bombardment continued except for a short pause now and again to mislead the enemy as to the hour the infantry would “top the parapet.”

At zero hour (dawn) 40 tanks were launched; of these 27 reached the first infantry objective, known as the Blue Line, and, of these 27, 26 went on to the second objective, the Black Line, and. 25 reached it.

The artillery bombardment and creeping barrage proved so effective that few of these tanks were ever called upon to come into action except round the ruins of Wytschaete village, where some snipers and machine-guns were silenced by then, and at Fanny's farm, near Messines, where our infantry were held up by machine-gun fire. One tank operating with the Anzac Corps got across the enemy's trenches at a very rapid rate and reached its objective on the Black Line, a distance of about 8,000 yards, in 1 hour and 40 minutes, having engaged an enemy’s machine-gun on the way. Another tank, rather aptly named the “Wytschaete Express,” led the infantry into the village of Wytschaete and helped to persuade the Germans defending it to surrender, which they did in large numbers.

At 10.30 a.m. the 24 reserve tanks were moved up to points behind our original front line, and 22 of these started with the infantry at 3.10 p.m. in

the attack on the Oosttaverne line, which constituted the final objective. During this phase of the battle the tanks rendered very great assistance to the infantry by occupying the ground beyond the Oosttaverne line before the infantry arrived, and so disorganising the enemy’s defence.

At a place named Joye farm an interesting incident occurred. Two tanks became ditched here, but, in spite of this and approaching darkness, these machines were in a position to repel any hostile counter-attack coming up the Wambeke valley, so it was decided to stand by in the tanks and resume unditching work at daybreak.

At about 4 a.m. unditching was started again, and one tank was got out successfully, but unfortunately broke its track soon afterwards in trying to cross the railway to advance against an enemy’s counter-attack which was developing. An hour later the enemy was observed to be massing in the Wambeke valley. The position of the tanks only allowed of a pair of 6-pounders being trained in the direction of the enemy, so the remainder of the

crews, under their officers, took up positions in shell-holes with their Lewis guns. Word was sent to the infantry to warn them and ask for co-operation, and on a reply being received that they were short of Lewis-gun ammunition, some was supplied to them from the tanks.

From 6.30 a.m. onwards the enemy made repeated attempts to advance, shooting at the tanks with a large number of armour-piercing bullets which failed to penetrate. They were driven off in every ease with heavy casualties, until at 11.30 a.m. our artillery barrage opened and dispersed them.

The battle of Messines, one of the shortest and best mounted limited operations of the war, was in no sense a tank battle. Tanks took but a small part in it, except in its final stages, nevertheless many useful lessons were learnt, the chief of which were: the necessity of some special form of unditching gear; the advisability of selecting starting-points well behind our front line (in this battle they were chosen too close behind it, with the result that as it

was still dark at zero hour several tanks got ditched in “No Man’s Land “); the advisability of selecting rallying-points well behind objectives, so that when tanks have finished their work their crews may gain as much rest as possible.