CHAPTER XXIV — TANK SIGNALLING ORGANISATION

IN battle, co-operation between the commander and his troops, and between the troops themselves, depends very largely on the efficiency of the signal organisation. In a formation such as the Tank Corps, the chief duty of which was close co-operation with the infantry, the necessity for a simple though efficient communication was fully realised by Colonel Swinton as far back as February 1916, when he wrote his tactical instructions for the use of tanks, extracts from which have been given in Chapter IV. Though time for instruction was limited, special wireless apparatus was prepared and men trained in its use, but as orders were received not to equip the tanks with this apparatus they were dispatched to France in August 191,6 without it

.

On September 11 the first instructions relative to tank signals were published with the Fourth Army operation orders; they read as follows:

“From tanks to infantry and aircraft:

Flag Signals

Red flag—Out of action.

Green flag—Am on objective.

Other flags—Are inter-tank signals.

Lamp Signals

Series of T’s—Out of Action.

Series of H’s—Am on objective.

A proportion of the tanks will carry pigeons.”

The use made of these signals is not recorded, and no time was available, until after operations were concluded in November, wherein to organise more efficient methods.

In January 1917 steps were taken to introduce into the Heavy Branch some system of signalling in spite of the many difficulties, the chief of which were:

- No personnel other than the tank crews could be

obtained.

- At most only two months were available for training.

- Neither the Morse nor semaphore codes could be read by infantry.

- The whole question, after careful consideration, was fully dealt with in “Training Note No. 16,” already mentioned.

The entire system of field signalling was divided under three main headings:

-

Local.

—Between tanks and tanks and tanks and the attacking infantry; also between the Section commander and the transmitting station, should one be employed.

-

Distant.—

Between tanks and Company Headquarters, selected infantry and artillery observation posts, balloons, and possibly aeroplanes.

-

Telephonic.—

Between the various tank headquarters and those of the units with which they were co-operating. The means of signalling adopted were as follows:

For local signalling coloured discs—red, green, and white. One to three of these signals in varying combinations could be hoisted on a steel pole. In all thirty-nine code signals could thus be sent, e.g.

white = “Forward”; red and white = “Enemy in small numbers”; red, white, green = “Enemy is retiring.” These codes were printed on cards and distributed to tank crews and to the infantry. Besides these “shutter signals” were also issued, but as they entailed both the sender and reader understanding the Morse code they were seldom used. The chief local system of communication was by runner, and it remained so until the end of the war.

Distant signalling was carried out by means of the Aldis daylight lamp, and as message-sending was too complicated a letter code was used, thus—a series of D.D.D...D’s meant “Broken down,” Q.Q.Q...Q’s “Require supplies.” Generally speaking, until November 1917, distant signalling was carried out by pigeons, which, on the whole,

proved most reliable as long as the birds were released before sunset; at a later hour than this they were apt to break their journey home by roosting on the way.

In February 1917 Captain J. D. N. Molesworth, M.C., was attached to the Heavy Branch to supervise the training in signalling. This officer remained with the Tank Corps until the end of the war, and in 1918 was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel and appointed Assistant Director of Army Signals in 1918. Under his direction classes in signalling were at once started and considerable progress was made in the short time available before the battle of Arras was fought.

In this battle the various means of communication laid down were put to the test of practical experience. The telephone system was described by the 1st Tank Brigade Commander as “heart-breaking.” “Many times it was totally impossible to hear or to be heard when speaking to Corps Headquarters at a distance of five to six

miles.” Pigeons were most useful, the Aldis lamp was found difficult, and many messages were sent from tank to tank, and in some cases to infantry with good results, by means of the coloured discs.

The experiences gained pointed to the absolute necessity of allotting sufficient personnel to battalions for purposes of signalling and telephonic communication.

The result of these experiences was that in May the first Tank Signal Company was formed, the personnel being provided from those already trained in the tank battalions, to which a few trained Signal Service men were added. The formation of this company was shortly followed by that of the 2nd and 3rd Companies, the 2nd Company taking part in the battle of Messines.

In May the first experiments in using wireless signalling from and to tanks were carried out at the Central Workshops at Erin, various types of aerials being tested. In July a wireless-signal officer was appointed to the Tank Corps and he at once set to

work to get ready six tanks fitted with wireless apparatus for the impending Ypres operations.

These signal tanks, when completed, were allotted to the Brigade Signal Companies, and in isolated cases, during the battle, came into operation, but in the main they did not prove a great success on account of the extreme difficulty of the ground. Eventually these tanks were placed at different points along the battle front and were used as observation posts by the Royal Flying Corps, wireless being employed to inform the anti-aircraft batteries in rear whenever enemy’s aeroplanes were seen approaching our lines. Many wireless messages were sent and much experience was gained by means of this work.

By the end of September, on account of signalling equipment being obtained, it was possible to carry out training on much better lines than heretofore. This was fortunate, for it enabled intensive signalling training to be carried out prior to the battle of Cambrai. During this battle a much more complete system of signals was attempted,

and wireless signalling proved invaluable in keeping in touch with rear headquarters and also in sending orders forward. On the first day of this battle a successful experiment in laying telegraph cable from a tank was carried out, five tons of cable being towed forward by means of sledges, the tank carrying 120 poles, exchanges, telephones, and sundry apparatus from our front line to the town of Marcoing.

The signalling experiences gained during the battle of Cambrai proved of great value, the most important being that it became apparent that it was next to useless to attempt to collect information from the front of the battle line. Even if this information could be collected, and it was most difficult to do so, it was so local and ephemeral in importance as to confuse rather than to illuminate those who-received it. Collecting points about 600 yards behind the fighting tanks were found to be generally the most suitable places for establishing wireless and visual signalling stations

.

At these stations officers were posted to receive messages and to compile them into general reports, which from time to time were transmitted by wireless to the headquarters concerned.

After the battle of Cambrai the 4th Brigade Signal Company was formed. This Company was the first one to have a complete complement of trained Signal Service officers and men allotted to it. It carried out exceptionally good work during the operations in March 1918.

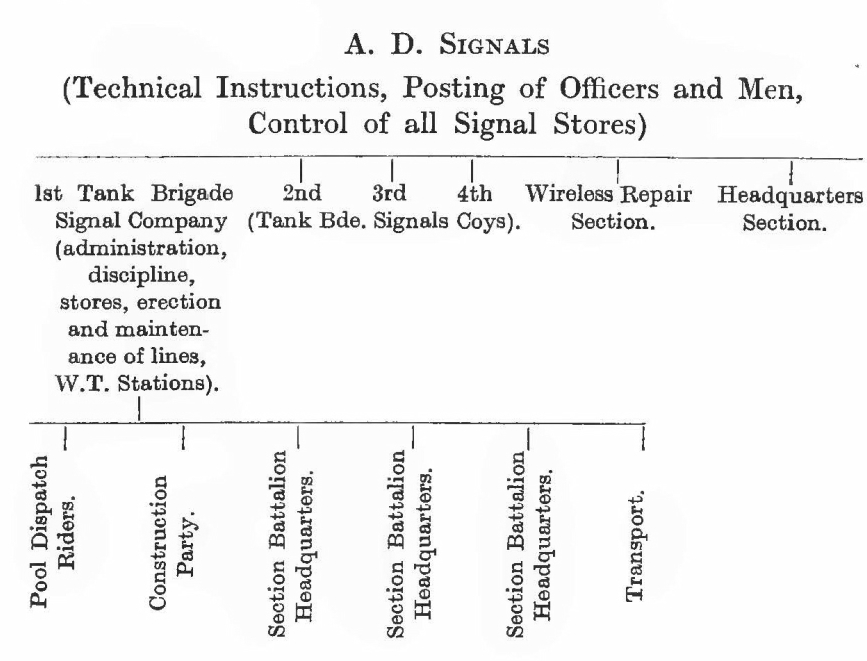

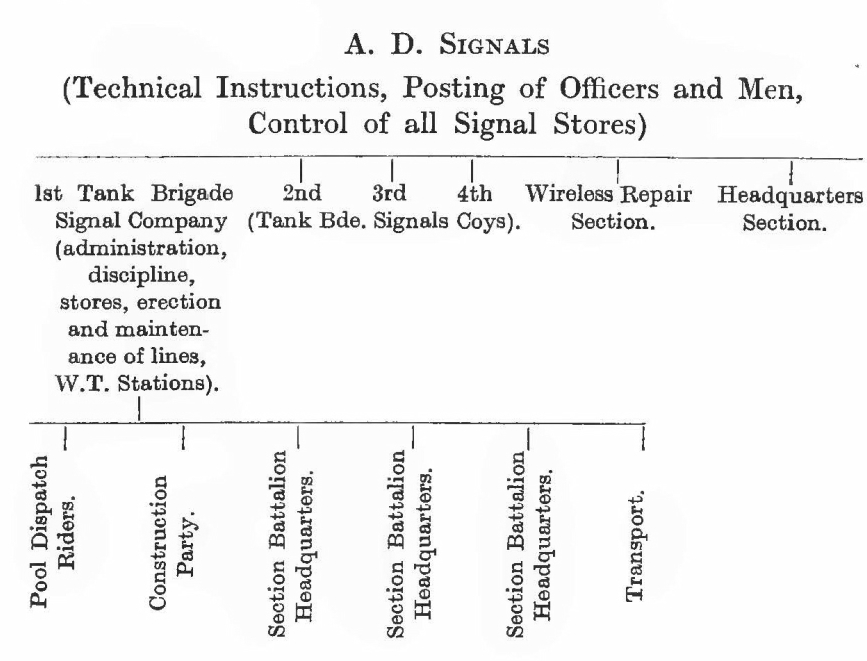

At this time the complete organisation of signals in the Tank Corps may be shown graphically as follows:

Early in 1918 the type of wireless apparatus as used in the signal tanks was changed to C.W. (continuous wave) sets, these being more compact, and greater range of action being possible with the small aerials the tanks had to use.

Eight of these C.W. sets were issued to each Brigade Signal Company, and training in their use was carried out up to the commencement of the August operations. On the whole they proved a success and justified their adoption, but as experience was gained it became evident that something better and stronger was wanted

.

In September a scheme was devised’ whereby the entire signal organisation of the Tank Corps was to be recast so as to fit in with the new tank group system, which was then being worked out for 1919. This organisation included Group Signal Companies and much larger Brigade Signal Companies than had hitherto been used, and the main type of apparatus that this organisation was to use was wireless. Only one set of wireless to each tank company was to be employed actually in tanks, the other stations being carried forward in box cars so as to render them more mobile.

The importance of signalling in a formation such as the Tank Corps cannot be over-estimated, and this importance will increase as more rapid-moving machines are introduced, for, unless messages can be transmitted backwards and forwards without delay, many favourable opportunities for action, especially the action of reserves, will be lost. Making the most of time is the basis of all success, and this cannot be accomplished unless the

commander is in the closest touch with his fighting and administrative troops and departments.