5

The Energies of Attachment

The Nitty-Gritty of Intimacy

[The infant’s] profound attachment to a particular person is both as strong as, and often as irrational as, falling in love, and the very similarity of these two processes suggests strongly that they may have something in common.

—JOHN BOWLBY1

While your Energetic Stress Style is inherited (Donna can see it in the energies of a newborn infant), the way you bond to others, called your attachment style, is to a large degree a product of learning. Behavioral scientists have studied in-depth the way your early experiences are likely to impact your adult relationships.

How the Infant Brain Gets Wired

At birth, your brain was a book whose story line was yet to be written. The pages, the binding, and overall organization were already apparent in their embryonic forms, but the words had not yet been inscribed. Your genes determined the basic structure of your nervous system and even primal temperamental patterns, but the early experiences that would come to shape the life you are now living would only unfold as a result of your interactions with your environment.

While the mutual influences of nature and nurture are no doubt familiar to you, what you may not know is how directly the neural pathways in your developing brain were impacted by the subtle and not-so-subtle ways your primary caregivers responded to you. Life was a stream of sensation. Hunger pangs would intrude into a peaceful rest. You would cry reflexively. If you were met with soothing words, a tender embrace, and the taste of warm milk, all was good again. The neural pathways that would eventually form meaning about hunger pangs would not link to neurons that activate anxiety. Hunger would eventually become associated with positive expectations. If, however, your cries went unheeded, that episode established a different set of pathways. Hunger was not only a temporary pain. It became pain laced with anxiety, uncertainty, and negative anticipations.

• THE ENERGY DIMENSION •

Infant Being Nurtured

When an infant’s needs are responded to promptly, it is very beautiful. The surrounding aura moves in toward the baby and then gently moves away. This steady rhythm comforts the body like a pulsating warm blanket, keeping all the baby’s energies in a tender glow.

Infant Being Neglected

When an infant is crying out of unmet need, the energy reaches out toward the caregiver, but it looks confused. It is disorganized and sometimes jagged. When the baby finally stops crying from exhaustion, the energies are pulled back from the world, the aura looks collapsed and thin, and its natural pulsation seems subdued.

As an infant, you could not soothe your discomforts. While the part of your nervous system that mobilizes action in response to stress and pain (the sympathetic nervous system) was already well developed by the time you were born, the part that would allow you to soothe yourself in the face of distress (the parasympathetic nervous system) was still undeveloped. Nature gave that job to your parents, counting on them to soothe you and to teach you about soothing yourself. When discomfort roused you into action, your repertoire was limited mostly to squirming and crying. When your caregivers held you and cuddled you and cooed soothing sounds, you were not only comforted; you learned about self-comforting.

These early learnings shaped your most basic assessments about yourself and your relationships. They told you whether you were worthy of intimacy, confirmed whether or not you could rely on your intimates for support and protection, showed you how to care for and be cared for by those to whom you were closest, and guided you in how to manage your emotional needs.

Early Imprints of How to Be in a Relationship Are Usually Lasting Ones

In the wild, a child’s survival depended on establishing a close bond with whoever would provide care. The infant’s brain is wired to seek, bond, and communicate with a caregiver, and it is from caregiver relationships that skills for self-nurture and relating intimately with others are, for better or worse, formed. John Bowlby—the British psychiatrist who blazed the trail for our current understanding of the infant’s attachment to a primary caregiver and its lifelong impact—provocatively claimed in 1951 that the young child’s hunger for the mother’s love and presence was as primal a drive as the hunger for food.2 No survival without food, but also no survival without nurture and protection. And bonding is the route to securing each. The baby is driven by inner forces to seek proximity and contact with the caregiver.

Bowlby’s assertion that the child’s need to bond is as primal as the need for food was put to a test a few years later in classic experiments by Harry Harlow. Baby rhesus monkeys would bond to and seek comfort from a terry-cloth mother they could cling to, though it provided no food, rather than to a wire mother outfitted with a nipple that provided milk.3 Infant monkeys placed in an unfamiliar room with their cloth surrogate parent would cling to it until they felt secure enough to explore. If the cloth surrogate was not present, they would crouch and freeze in fear, perhaps also rocking, sucking, crying, or screaming. This behavior was displayed in the absence of the cloth surrogate even if the wire surrogate—which they had suckled but could not physically embrace in a manner that produced bonding—was present. That primal is the infant’s drive to bond with a caregiver.

In the infant’s impulse for attachment, the sight of the caregiver’s face, hands, and hair are triggers for grasping and clinging. The caregiver’s voice and caresses initiate smiling and babbling behavior. Communication had to, of course, first be accomplished without words. Facial expressions, eye contact, voice tone, gestures, postures, timing, and intensity showed on the outside what was happening to you on the inside.4 Before you could talk, this was the primary information available to your caregivers about your moment-to-moment experience. The accuracy with which they read and were able to respond to your needs determined a great deal about your sense of well-being. Their attunement or lack of attunement was your first, deeply imprinted lesson about what to expect in a close relationship.

These early imprints are usually lasting ones. Bowlby compared the sweeping effects of maternal deprivation on psychological development to the impact of poor nutrition on physical growth.5 His first speculation on the role of early emotional deprivation traced to experiences prior to his psychiatric training when, as a volunteer at a residential school for delinquent and other troubled children, he noticed how some children would show anger and rejection even to those who tried to befriend them. Their self-defeating interpersonal styles seemed to have been established during their troubled home lives.

Fast-forward eighty years. Study after study suggests that early attachment relationships set the foundation for subsequent personality development. Infants who enjoyed a secure attachment relationship with a primary caregiver, as inferred by systematic assessments, grew up to have higher self-esteem than children whose primary attachment relationship was insecure. They also developed closer friendships, greater social competence, more fulfilling romantic partnerships, greater capacity to regulate their emotions, more ability to accomplish their goals, greater resilience, enhanced leadership qualities, and less anxiety and depression.6

• THE ENERGY DIMENSION •

Infant in a Secure Moment

The infant’s energy moves outward into the world, whether or not an adult is there. It is as if the energy is exploring the environment. Then it comes back in and soothes the infant. Then back out into the surrounding world. Like the breath, the energy moves inward, bringing the infant support and harmony, and then outward, securely contacting the world.

Infant in an Insecure Moment

The energies look confused, disorganized, and chaotic. Because the infant can’t make sense of what is happening and can’t control it, there is a surrender into powerlessness. The energies do not focus or coalesce, and they become disconnected from the environment.

Secure Attachment; Anxious Attachment; Avoidant Attachment

We are wired to bond to only a small group of intimates, with one special person at the top of the hierarchy, and it is during times of threat or separation that this wiring is most strongly activated. However, the way we will react when it is activated is shaped by our experiences. The dynamics of “secure” and “insecure” attachment styles have been investigated in hundreds of studies.

Secure Attachment

Secure attachment in childhood sets the stage for greater ease with intimacy as an adult. People with a secure attachment style tend to be optimistic about their primary relationship. They have a strong sense of self-worth, expect closeness, warmth, and comfort in their relationships, and they tend to find it. They are effective in communicating their needs and feelings, and they accurately read and respond to their partner’s emotional cues. They are able to soothe as well as self-soothe, and they are capable of moving easily between intimate engagement and independence, leading to the emotional and behavioral interdependence required for a successful relationship.7

Insecure Attachment

Insecure attachment in childhood sets the stage for later troubles with intimacy. Children who are insecurely attached did not receive the imprinting from their caregivers that would help them learn to regulate their own nervous systems, making them vulnerable to emotional difficulties throughout life.8 Insecure attachment generally involves anxious clinging or emotional avoidance in intimate relationships:

ANXIOUS ATTACHMENT

Anxious attachment is typified by a strong need for closeness, worry about and preoccupation with the relationship, and reliance on strategies such as clinging, angry, and controlling responses that attempt to minimize the emotional distance from the partner.9 People with an anxious attachment style tend to be extremely sensitive to small fluctuations in their partner’s moods and behavior, to take them personally, and to be easily upset by any sign of real or imagined distancing. Because they may alternate between clinging when their partner is available and showing anger because of times their partner was not available—or refusing comfort for that reason—this attachment style is sometimes called anxious-ambivalent.

• THE ENERGY DIMENSION •

Secure

The aura is full. It fluctuates easily in response to others, influenced by them but then returning to center. There is also a fullness in the chakra energies, which reach out in front of the person as if to greet others. This fullness in the aura and the chakras is soothing, leaving the person less dependent on others for emotional and energetic support.

Anxious

The energy of an anxious aura is jittery, its patterns unstable. Sometimes it will engulf or cling to the partner’s energies. Other times it will repel them or appear to attack them. This makes it difficult for another’s energies to connect and dance with those with an anxious-avoidant style.

Avoidant

The energy is pulled back into the avoidant person, or it focuses or fragments in other directions, any direction but toward a person where commitment might be called for. This may be toward projects, acquaintances, casual social situations, entertainment, surfing the net, or intellectual pursuits.

AVOIDANT ATTACHMENT

Avoidant attachment is typified by exaggerated self-reliance and strategies that maximize emotional distance from the partner.10 Adults with an avoidant attachment style tend to be isolated, unaware of their emotional hollowness, and put off by any suggestion that they might have more needs for intimacy than they recognize. They view their emotional detachment as a sign of strength and independence. Research, however, shows that when the relationship is at risk, individuals with an avoidant attachment style are just as distressed on physiological measures (such as the galvanic skin response) as other people. They are simply better at keeping themselves from expressing or even experiencing such thoughts and feelings.11 Avoidant partners have the same core need for a primary relationship but manage it by attempting to deny it.

MIXED ANXIOUS/AVOIDANT ATTACHMENT

Mixed anxious/avoidant attachment is a combination of both strategies, characterized by seeking closeness and then fearfully avoiding it. A traumatic or abusive relationship with a primary caregiver is often found in the person’s history. Borderline personality disorder often corresponds with an anxious/avoidant attachment style (which is sometimes called disorganized attachment). Closeness with the partner is longed for as a source of comfort and intimacy, but at the same time, intimacy provokes fear and anxiety. Anxious/avoidant attachment is typified in the quip, “If you won’t leave me, I’ll find someone who will.” This paradoxical style is relatively rare but can be extraordinarily challenging for the partner.

—

While the descriptions of attachment styles are, by necessity, of “pure types,” human beings are rarely pure types within any classification. A given individual may be a mix of these qualities or more like one type in a particular situation and more like another in a different situation, and the person’s primary attachment style may also shift over time.

The potential for developing a secure attachment style is there in your genes. It is what nature intended. But the way this capacity manifests or doesn’t manifest is shaped by your experiences. Secure attachment helps individuals, intimate relationships, and human communities thrive. Even though no parent is perfect, nature teams with the family to achieve secure attachment more than half of the time.12 The rest are divided fairly evenly between the anxious and the avoidant styles, with a minority having the disorganized anxious-avoidant style. However, such classifications don’t capture the rich nuance in an individual’s ways of relating intimately. Even within the “secure” majority are innumerable traits and habitual patterns that may dampen or strengthen intimacy.

When the attachment bond is strained or threatened by the inevitable hurdles in building any close, creative relationship, primal responses that trace back to early attachment experiences are evoked. Understanding how your style and your partner’s style were once upon a time adaptive strategies for less than perfect circumstances allows you, when such primal responses erupt, to proceed with greater compassion for yourself as well as for your partner.

• THE ENERGY DIMENSION •

When Donna witnesses couples interacting, the choreography of their energies is exactly the way you might imagine it to be:

Secure Relating

When two people engage intimately during a secure moment, the energy interchange Donna observes is smooth and strong. That is exactly what would be predicted by the “smooth, ordered, coherent patterns” that spectral analysis revealed in the electromagnetic field radiated by the heart during moments of love or appreciation.13

The Anxious Style in Relationships

The energies around a person with an anxious attachment style seeking contact with an intimate partner who is not responding in the moment tend to become disorganized and move somewhat chaotically but forcefully toward the partner.

The Avoidant Style in Relationships

The energies surrounding a person with an avoidant attachment style tend to contract so much that they take on what looks to Donna like a shell. These compacted energies then retreat from an intimate partner who is making an emotional demand. In interactions with others, the avoidant partner’s energies may be much more fluid and engaging. This corresponds with clinical observations. People who seem well adjusted and at ease in most social situations may still use an avoidant (or an anxious) attachment style in their most intimate relationships.

The Anxious-Avoidant Trap

Combining the above two descriptions provides a vivid picture of what has been the “anxious-avoidant trap,” in which one person’s energies move toward the other and the other’s retreat inward or move away.

Is your attachment style—whether secure, anxious, or avoidant—also reflected in the electromagnetic energies emanating from your body? Of course our answer is yes. One of the most interesting discoveries for David as he learned about Donna’s work is that memories, emotions, and behavioral programs are stored not only in the brain but also in the body’s energy systems. The secure, anxious, and avoidant ways of responding when feeling distressed are not just products of your mind. They are visible to Donna as patterns of energy.

The Dance of David’s and Donna’s Attachment Styles

We will once again feature our relationship in discussing how the principles discussed play out, not because it is an ideal model, but because we’ve had to struggle with and work through so many issues and some of them may resonate with you. Anxious or avoidant strategies—pursuing or retreating—are the two basic ways a child can respond when caregivers are not able to meet the child’s needs. For instance, David’s mother tried to breast-feed him but was unable to produce the amount of milk his body required. A determined woman, she kept trying for three weeks, as he approached semistarvation, until the doctor insisted that his diet be supplemented. So David’s earliest formative experiences, about so basic a drive as chronic hunger, were that no matter how much he cried, he was not going to get what he needed. With consistent physical or emotional deprivation, the infant finally stops seeking the caregiver’s attention, dampens internal sensations, and withdraws—avoidant attachment in the making.

For David, this was reinforced because the wisdom of post–World War II child experts was to feed on a schedule and not soothe or reinforce the infant for crying. Family legend has it that Mr. and Mrs. Cohen, an elderly couple who were renting a room in the same Brooklyn tenement where David’s parents were staying during David’s first year, would cry themselves to sleep each night hearing David’s unheeded screams through the thin walls and being powerless to override the child experts of the day and intervene. Children will finally stop screaming and retreat within. Such experiences laid the foundation for David’s attachment style. They combined with his being an only child, and one who had no age-matched playmates in the neighborhood, into the development of a boy who was comfortable spending long periods alone, who tended toward self-soothing rather than sharing his vulnerabilities with others, and who was not at ease in the casual emotional give-and-take that seemed natural to his peers.

He grew up proud of his independence and self-sufficiency. He did not view his style as an avoidant attachment disorder, though his failure to form a lasting partnership despite a number of intense romances during his twenties might have been a clue. He couldn’t understand why his relationships, which usually started with strong passion, would deteriorate into an emotional roller coaster where his partners felt he was not giving them what they needed. It seemed patently obvious to him that their neediness and emotional volatility were what was pushing him away. This initial attraction between a person with an avoidant attachment style and a person with an anxious/clinging style has been characterized in literature as the “anxious-avoidant trap.”14 If an avoidant person with David’s aptitude for the role gets close enough even to a relatively secure partner, however, the partner may still be drawn into this anxious-avoidant dance.

David was thirty when he met Donna. After so many experiences where his paramours became wounded puddles of emotion, and with no inkling of his role in inflicting the wounds, Donna’s independence and self-reliance were very attractive to him. She was the middle child of three. While her older sister was still commanding special attention as the firstborn, their little brother came along, eighteen months after Donna, with some special needs, and Donna was in many ways left to fend for herself. In assuring her young second daughter that she would be fine, though she got relatively little parental attention, Donna’s mother would say to her, “The Lord protects angels and fools. I’m not sure which you are, but I know you are protected.” As you will see in chapter 7, Donna learned self-sufficiency. In her first marriage, her emotionally remote husband would be away for long periods and her self-reliance was all she had for bringing up their young daughters. When we met, we each wanted a lot of space and were happy to give the other a lot of space. But the self-reliance that is an effective way of coping when no one is available can be a liability for forming a lasting intimate relationship. It can also be a bit of a delusion. People identified in scientific studies as being secure in their primary relationships were not only capable of greater intimacy and interdependence, they were more autonomous and independent.15

Being with a partner whose strong self-reliance can trump intimacy has been part of the journey for each of us—sometimes propelling one of us or the other into the anxious/clinging polarity of self-reliance as we have traveled together for well more than three decades toward more secure attachment styles. Attachment style is not rigidly fixed, may shift with the context, and may become more secure over time.16 Our tumultuous ride has transformed us both, so we know what is possible, as well as how challenging the journey can be.

Obviously, however, not all adults have an intimate partner or are in a relationship that is meeting their basic needs for closeness, security, love, and support. Does this mean they drew the short straw and must lead empty, emotionally barren lives? By no means. Some people seem well suited for single life. Particularly if your early attachment experiences provided you with healthy internal models for self-care, you are poised to manage your emotions effectively, to soothe your own sorrows, and to self-validate in the absence of a primary partner. Many single people do indeed find enough of the emotional benefits that might be provided by an intimate relationship to do very well. Nonetheless, there are strong reasons that people who are in fulfilling partnerships tend to live longer, healthier, happier lives than those who are not.17

The Influence of Your Energetic Stress Style on Your Relationship Style

The years have proven that Donna, as a kinesthetic, was more readily capable of intimate connection than digital David, but her self-reliance made her so tolerant of emotional distance that David’s avoidant style set the tone for both of us. Your Energetic Stress Style—visual, kinesthetic, digital, tonal—is an aspect of your inborn temperament that we believe influences your attachment style throughout your life.

It is not hard to understand how your Energetic Stress Style would interact with your attachment history in forming and maintaining your patterns of intimacy. Donna’s kinesthetic orientation countered the early experiences that might have produced a person with a more avoidant attachment style. Although she had a high tolerance for distance based on her early experiences, her kinesthetic nature allowed her to also easily resonate with whatever bids for closeness her parents, and later David, managed to express and meet them there. David’s digital orientation, on the other hand, amplified the early experiences that fed into his avoidant style. Digitals tend to cut off emotionally from themselves and from their partners, so it is a double whammy to be a digital whose early experiences forged an avoidant attachment style. Learning to soothe oneself instead of seeking contact and support (risking feelings of vulnerability and dependence) combines with the digital’s more insular ways of relating—which favor mental retreat over emotional engagement. This is a recipe for a seriously avoidant attachment style.

The Interaction of Energetic Stress Style and Attachment Style

As we were trying to convey how the digital stress style can amplify an avoidant attachment style, David bravely ventured, “Okay, Donna, let’s tell the folks what this looks like in me energetically.” Her analysis: “Sometimes you are in a digital bubble. And you show no interest in leaving it to enter my world. If we’re having a difficult time and I’m desperately trying to reach you, that bubble looks like a thick, impenetrable wall. Other times it is just where you go when you are involved in a project. The bubble is not so thick, but it is still not easy to penetrate. And when I do penetrate it, it is like I have disturbed you from a dream, like I have literally burst your bubble. You don’t transition easily from that space to meet my energies. I’ve come to understand that this is your nature and to not take it personally that you are such an automaton. And to appreciate that at so many other times, you are fully and readily present.”

The “motto” that typify each sensory mode (here) provide insight into the way Energetic Stress Style interacts with attachment style. You can see how the kinesthetic’s “I don’t want you to suffer or feel wrong” reinforced “I don’t want to cause trouble” and played into Donna’s allowing David’s avoidant style to set the tone for the relationship. An overlay of the digital style’s “I’m right!” is to not question the role of his or her own behaviors in the lack of intimacy. An overlay of the visual’s “You’re wrong!” is to blame the partner for the difficulties the relationship encounters. Meanwhile, the tonal’s “I’m angry at you for making me feel wrong!” undermines the partner’s efforts toward being close. Tonals whose backgrounds led to an anxious attachment style are dealing with another double whammy, quite different from that of the digital. As tonals, they characteristically read between the lines and, when stressed, negatively distort their partner’s intentions. If they in childhood also developed an anxious attachment style, they will be overly sensitive to tiny nuances in their partner’s mood. With those two filters acting in concert, it is not surprising that they tend to feel emotionally abused and abandoned by their partners. Being aware of the filters you characteristically use when under stress, and those your partner tends to use, will provide a helpful backdrop as you move toward more secure attachment.

What Does All This Mean for Your Relationship?

Does the scientific understanding of attachment mean that in order for you to have emerged from your childhood psychologically unscathed your parents needed to have anticipated your every need, correctly read your every gesture, and soothed your every discomfort? Nature knew better than to set the bar at that level. The concept of the “good-enough” parent recognizes that no one can always interpret a child’s signals correctly, avoid separations, or hit the bull’s-eye with every attempt to soothe.18 A child’s innate programming to thrive is remarkably robust. Doses of adversity and want build self-reliance even as the neural pathways for secure bonding seem to require a somewhat steady accumulation of positive interactions with the caregiver. Children are naturally resilient, so even imperfect parents, as all parents are, are able to raise healthy kids.

Many people, however, didn’t have even minimally “good enough” parenting, or at least there were areas of breakdown, and problems in their adult relationships often trace back to these earlier lapses. Are these patterns indelibly stamped on your psyche? For most people throughout history, the answer was “probably yes.” Attachment style during childhood is likely to shift only if significant external changes occur, such as a divorce, the onset of chronic depression in a parent, or the entry of a different primary caregiver.19 As people develop into adulthood, the tendency is to choose partners and situations that correspond with and reinforce early psychological patterns.20 In this sense, the past predicts the future. What people receive from their parents sets into motion deep patterns they usually bring to their marriages.

The hopeful and encouraging reason for this section of the book is that the possibility of repairing wounds and compensating for damages tracing to fallible parenting and unfavorable circumstances is now open to anyone willing to invest the time and effort. Even in infancy, programs that improved the quality of interaction between a mother and a child who evidenced early attachment problems resulted in more positive mother-child relationships that included significantly less anger, avoidance, and resistance.21 For instance, it is well established that babies who are irritable from birth are less likely to create secure bonds at the end of their first year and are more likely to be anxious than infants who are more tranquil. However, early adjustments in parenting style can yield quick and significant results. In a Dutch study, mothers of babies diagnosed as “highly irritable at birth” were given three counseling sessions of two hours each, when their babies were between six and nine months old. By the time they were one year old, 68 percent of these infants were “securely attached.” Only 28 percent of a matched control group that did not receive this counseling were “securely attached” by age one.22

Attunement between Infant and Parent

In one another’s presence, the auras of the infant and the parent grow larger, and another field appears that surrounds the pair, ensconcing them in a cocoonlike energy. This is like a third aura, a property of infant and parent as a unit.

Non-Attunement between Infant and Parent

Depending on the quality of the relationship, the shared energy will differ. In general, the two auras will not overlap. If infant and parent are interacting but in a non-attuned manner, the infant’s aura sucks further into itself and starts disconnecting from the environment. If the parent is angry or exasperated, a forceful energy that is threatening and confusing will move toward the child, sometimes causing the child to energetically retreat but other times literally entering the child. When the adult’s more powerful energy enters the child’s, it creates an energetic bridge for the transmission of beliefs as well as emotions. We are all familiar with how children may take on their parents’ judgments and worldview as their own. This starts in the energies and can grow out non-attunement as well as out of the attunement in which you would expect it.

What occurs in our lives beyond childhood can also have a strong impact on our bonding behavior. Favorable life events, such as successfully moving into the role of parenthood or forming a relationship with a partner whose attachment style is healthy and secure, can help transform an insecure attachment style.23 So can individual psychotherapy, couple counseling, or other efforts that improve a challenging relationship.24 It is never too late.

Attaching by Detaching

We will open our discussion of how to retrieve insecure attachment moments and begin to repair deep patterns with one of the simplest methods possible. If you have avoidant attachment tendencies, stay alert for times that you pull away from your partner and invite your partner to join you in this exercise. If you have anxious attachment tendencies, stay alert for times that you become clinging or controlling and do the exercise. In either case, when you realize you are caught in the attachment habits that do not serve your relationship, this simple wordless exercise can quickly interrupt the pattern, help you find your center, and open a path toward developing a more secure attachment moment with your partner. At such times of opportunity (we know—they don’t feel like opportunities), ask your partner to participate with you. That alone acknowledges your awareness of tendencies in yourself that hurt the relationship and of your intention to overcome them. Your partner will probably find this encouraging in itself and cause for appreciation or at least hope. The exercise begins by coming into yourself and establishing an internal sense of safety. That is, you will, ironically, begin to enhance your capacity for healthy attachment by detaching. Then, as you become centered, you can turn back to your partner to energetically establish a stronger connection:

- Coming into Yourself. Sitting directly across from your partner, both of you place your hands on your chest, close your eyes, and keep your focus on your heart for three deep breaths or until you are feeling more calm, safe, and centered.

- Softly Reconnecting. When you are both ready, look at your partner’s hands while keeping yours over your chest. Allow yourself to simply be with this connection for three more deep breaths.

- The Secure Gentle Gaze. Lift your eyes and meet your partner’s eyes. Feel an energetic bridge between you reconnecting. If this becomes difficult, return to step one and continue through the exercise until you can securely engage one another’s gaze.

Simple as it is, this exercise is powerful. Starting when you are caught in the energy of an old and dysfunctional way of relating, it begins to repattern your nervous system. Each time you do the exercise, you are building a stronger energetic foundation for secure attachment.

• THE ENERGY DIMENSION •

Deep Breathing

The simple act of taking a deep breath engages a branch of the vagus nerve that slows the cardiovascular and respiratory systems in ways that allow us to relax and be present with one another. Taking a long deep breath when stressed not only slows respiratory and cardiovascular processes, it also smooths the movement of energy in the meridians, chakras, and aura. It counteracts the “rigid-alert” energy configuration of distress.

Heart Connection

When you bring your consciousness to your heart, you evoke feelings that are more positive and loving. The energies of these feelings not only travel to your cells, organs, and through your entire body, your heart’s expanded electromagnetic field radiates outwardly and will impact anyone around you.

The Gentle Gaze

When you are open and relaxed and your eyes gently meet your partner’s, the energies connect, but not as a straight line. Rather they look like a soft, hazy suspension bridge between your eyes and your partner’s. As your eyes stay in contact, the energies in this downward curve begin to loop upward, eventually taking on the form of a figure eight between you. This connects you and actually grows stronger for as long as you remain in comfortable eye contact. When the figure-eight energy has grown quite strong, it will continue to connect you even after your attention has shifted from one another.

How Triple Warmer Maintains Your Attachment Style

An energy system identified by ancient Chinese physicians and given a strange name has an invisible but emphatic impact on your attachment style. It is called Triple Warmer.

The infant needs the caregiver’s nurturing and protection in order to survive. The foundational issue for attachment strategies, deeper even than the need for love and affection, is safety. Safety is the domain of Triple Warmer. It is the energy system in your body that is charged with responding to any threat to your survival. The Triple Warmer energy system—invisible yet as real as your cardiovascular or respiratory systems—supports your survival in three basic ways: It governs your immune system; it orchestrates responses to external threat, such as whether to fight or flee; and it maintains habits that are geared toward keeping you out of danger.

How Triple Warmer Keeps You from Changing

In carrying out these three basic survival strategies, Triple Warmer reveals the remarkable intelligence of the body and its energy systems. Consider, for instance, your immune response. Your body’s surveillance energies are continually on alert for invading bacteria and other harmful intruders, and they initiate complex, ingenious strategies to destroy and dispose of them. Anyone who examines the workings of the immune system realizes that immense intelligence is involved. Triple Warmer uses an analogous strategy to that of the immune system for keeping you safe in the outer world. It assesses the information brought in by your senses. When it recognizes a potential threat, it implements preprogrammed behavioral strategies (just as your immune system implements preprogrammed biochemical strategies) that evolved because of their survival value for your ancestors. All this occurs without the need for your intellect or even your conscious awareness.

Triple Warmer approaches its mission of keeping you safe by working in concert with the hypothalamus. While Triple Warmer is an energy system, your hypothalamus is a tiny organ, an almond-sized gland that governs your autonomic nervous system. The hypothalamus is the highest up on the chain of endocrine glands, regulating the hormones that influence much of your emotional life, from how you bond to what you do in the face of threat.

Both Triple Warmer and the hypothalamus are oriented toward advancing the same ends: your safety and well-being. The way they work together is reminiscent of a computer and its software. As a physical structure, the hypothalamus, like a computer, has relatively fixed wiring. Triple Warmer (or any other energy system) is much more flexible and responsive, more like your word-processing software. You can create a poem, a blog entry, or a thriller novel. The software tells the computer what to do based on the input from the keyboard. Your body’s energies, which are responsive to the ever-changing input from the environment and from within, are always at the “keyboard,” telling your body what to do. Triple Warmer tells the hypothalamus which hormones and other chemicals to produce and disperse. Your mood, automated thoughts, and behaviors follow.

Triple Warmer evolved during the preponderance of human history when physical threat was part of daily life. When a saber-toothed tiger walked into the cave of your ancestors a hundred thousand years ago, Triple Warmer worked in partnership with the hypothalamus. They diverted bloodflow away from digestive, reproductive, and other systems not involved with immediate survival, and directed it toward systems that support fighting, escaping, or freezing to become less detectable. Triple Warmer also learns. It was continually establishing new survival habits for your ancestors, such as creating an aversion to the kinds of caves frequented by saber-toothed tigers or to the smell of a predator that just moved into their territory. Triple Warmer, in fact, still maintains innumerable survival habits tracing to your ancestors. These operate largely beneath your awareness, and Triple Warmer is quite unyielding about giving up habits or programs that were designed over eons to ensure survival. After all, you are here. It worked!

• THE ENERGY DIMENSION •

Triple Warmer at Rest

Even when there is no perceived threat, Triple Warmer is usually still on alert. So Donna rarely sees Triple Warmer at rest. When it really is at rest, it fades into the background and seems to play more of a supportive role. You don’t so much see Triple Warmer then, and with the safety that is signaled as Triple Warmer relaxes, the meridians become stronger, the chakras more vital, the radiant circuits activated, and the aura more full. You see the impact of a peaceful Triple Warmer in all the other energy systems.

Triple Warmer in the Face of Threat

When an immediate danger is detected, Triple Warmer orchestrates all of the body’s energies to deal with the threat. They become sharp and focused. A cascading energy from the aura above the head and into the physical body prepares it for fight or flight, activating stress chemicals. If the response is to be flight, the energy leaves the face and upper body and goes into the legs to support their ability to run. The blood flow follows these energies, directing extra blood to the legs. If the response is to be fight, energy goes into the face and pumps up the arms and chest, which is also followed by the flow of blood.

Triple Warmer Maintaining a Habit

Triple Warmer regulates the activities of a spectrum of energy systems that are involved with habits that were formed in an attempt to ensure survival and well-being. For instance, the aura includes a band that holds the energy of established habits and behavioral patterns. When someone is in a situation that evokes a habitual emotion or behavior—whether the habit is an effective one or a dysfunctional one—this band becomes more pronounced. Triple Warmer’s role in this orchestration becomes most obvious when the person tries to change the habit. Then Triple Warmer’s energies rise to preserve the habit. Triple Warmer is a conservative force that is not oriented toward change. You’ve survived this long with the habit, so Triple Warmer has no incentive to change it! A similar process occurs at the level of the chakras. Habitual anger may too often scream out from the Third Chakra (solar plexus). Excessive compassion may ooze out from the Heart Chakra. Energy may move up quickly from the Root Chakra when your safety or sense of self is threatened. Triple Warmer is at the foundation of these reflexive responses, and if you try to change them, Triple Warmer’s energies become activated in an attempt to retain the status quo.

The challenges and stresses of modern life, however, are far different from those in the world that existed while Triple Warmer was evolving. So Triple Warmer’s brilliant programming is keyed to a world that no longer exists. Beyond its outdated strategies, Triple Warmer does not discriminate particularly well between life-threatening situations and relatively benign events. If you go into threat alert or full fight or flight or freeze mode half a dozen times a day—when your daughter won’t obey you, when you are late for an appointment, when your computer isn’t cooperating—the cortisol and other stress chemicals that are generated accumulate in your body and become harmful in a multitude of ways. Your risk then increases for anxiety, depression, digestive problems, heart disease, sleep disorders, weight gain, and concentration difficulties—collateral damage of Triple Warmer’s survival strategies. In trying to save you, Triple Warmer is powerful enough to leave you with any of the symptoms mentioned above. It is the military-industrial complex of your body. Like the military, its job is to keep you alive and safe, and it is steadfast with that assignment, even if it means a lot of excessive effort, false alarms, inadvertent harm, and unsparing expenditure of precious resources to ensure security.

A peculiarity about Triple Warmer is that it won’t support your desire to change a habit, even a harmful habit. Its assessment much of the time, since it is using outdated maps, is that you are in territory that is not safe, and introducing change of any sort exaggerates that perceived danger. So Triple Warmer’s default response is to resist change. The habits and programs it maintains have kept you alive to this point, so it endorses every one of them. It is also uninterested in subtleties. It doesn’t care if you are happy or unhappy, only that you are surviving and safe. Operating beneath your consciousness and with its own agenda, Triple Warmer can be a formidable enemy of your intentions. Of particular relevance for this book, your attachment style is one of the behavioral systems Triple Warmer crafted to help you adapt to your childhood circumstances, and it does not readily allow it to transform.

Attachment and Triple Warmer

Triple Warmer is particularly reactive about your family and primary relationship. In addition to the attachment style formed during your childhood, your ancestors’ survival and propagation depended on their mate and clan, so Triple Warmer is alert for any disturbance in the interpersonal field. When it finds one, it can trigger an emotional tempest that leaves both you and your partner stupefied.

The concept that safety, the domain of Triple Warmer, is a core issue in attachment is revealed by the intensity with which couples argue. Who else would you fight with so passionately about disagreements you cannot recall the next day but the one you love? In fact, mammals have a special pathway in their brain that triggers “primal panic” when an attachment relationship seems endangered.25 When the love between you turns to tension and your collaborative alliance seems to be on the line, your primal instincts are activated. Your ancestors depended on their bond with a partner to survive and bring the next generation forward. When that bond is threatened—whether your overall attachment style is secure or insecure—you and what matters most to you do not feel safe. Triple Warmer goes into overdrive and your rational mind has little influence over what comes next! The Pact (Chapter 3) can restore the balance, but glitches in your attachment style can keep reigniting conflict and tension.

A way to bring your attachment style closer to the secure side of the secure-insecure spectrum is to keep Triple Warmer calm in situations that might trigger feelings and behaviors that are rooted in painful experiences from childhood. While Triple Warmer does not readily release its grip on its survival strategies, you will be more effective if you recognize that not only are you up against a powerful foe, but this “foe” evolved to be your friend. It is, in fact, still helping you stay alive, though it is confused by the plethora of circumstances that did not exist while it was evolving. A basic step you can take to improve your relationship with your partner is to bring Triple Warmer to a calmer default position. Energy medicine offers techniques for working directly with Triple Warmer to do just that. From this more favorable baseline, Triple Warmer is less likely to go into a threat response or to revert to attachment patterns from childhood that were formed in the face of threat or deprivation.

Retraining Triple Warmer

Triple Warmer can hijack your brain, propelling it into outdated fears and thought habits that are the antithesis of secure attachment. An effective approach for changing such habitual strategies is to communicate to Triple Warmer that you are safe in situations where it tends to initiate false alarms. How do you communicate with Triple Warmer? Triple Warmer’s language is energy, not words. The following three techniques realign the energies that impact Triple Warmer, bringing Triple Warmer into a more secure state even while you are actively recalling challenging moments in your relationship. The more Triple Warmer is helped in these ways to recognize that such situations do not constitute mortal danger or the annihilation of a primary relationship, the less likely it will overreact.

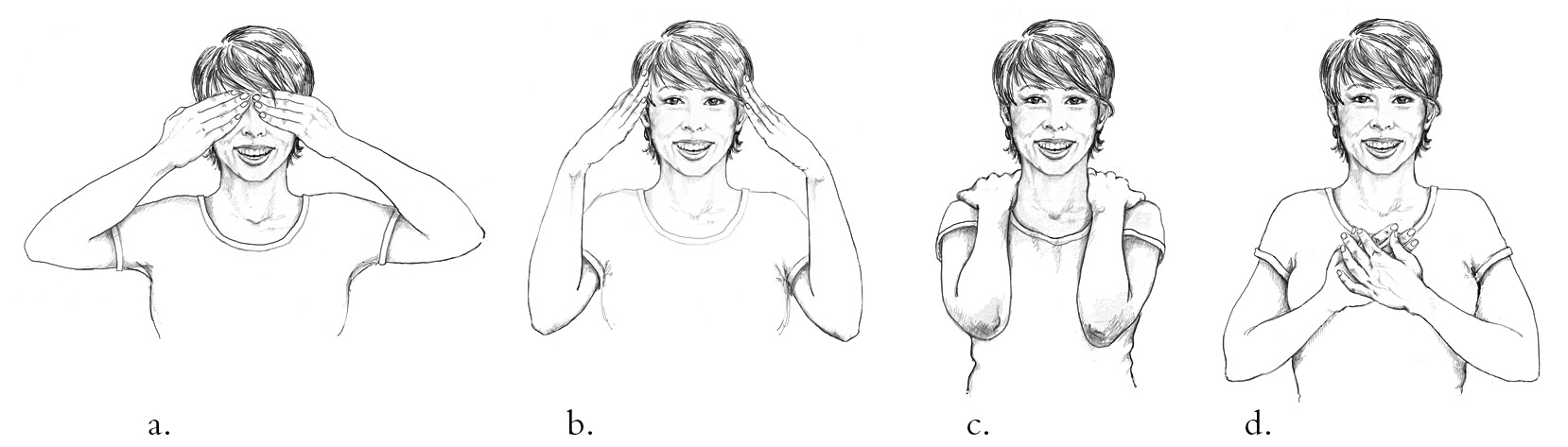

The Triple Warmer Smoothie

Triple Warmer has its own energy pathway. You can calm and sedate Triple Warmer by tracing your fingers over part of this pathway in the direction that reduces excess energy:

- Bring to mind a situation where you “lost it” with your partner. This can simply be a time that the two of you had a challenging interaction, but even better for this technique if it is an instance of an ongoing pattern.

- Lay your fingers sideways across your closed eyelids and take a deep in-breath (see Figure 5-1a).

- As you let your breath out, drag your fingers across your eyes to your temples.

- With your fingers at your temples, take another deep in-breath and bring your fingers up so they are just above your ears (see Figure 5-1b).

- As you let your breath out, trace around the back side of your ears with light pressure and go down the side of your neck.

- Lay your hands over the top of your shoulders and, with an in-breath, push your fingers into the back of your shoulders (see Figure 5-1c).

- Let your breath out as you pull your fingers hard over your shoulders and drag them down to the middle of your chest (Heart Chakra). Place one hand over the other (see Figure 5-1d).

- With several deep breaths, softly cradle in your heart the words, “I am safe!”

FIGURE 5-1 The Triple Warmer Smoothie

Triple Warmer Neurovascular Points

You have already learned, with the Stress Release Hold (here), to work with one set of neurovascular points as a way of turning off the fight/flight/freeze response and shifting the neurochemistry of stress. Triple Warmer’s neurovascular reflex points are at the temple and can be held along with the points on the forehead to shift outmoded habits of thought:

- Bring to mind a second situation where you “lost it” with your partner.

- Lightly place your thumbs on your temples and your fingers on your forehead (see Figure 5-2).

- Continue to keep the situation in mind during several deep breaths.

- The energy will begin to shift within a minute or two. End with the words, “I am safe!”

Heart Chakra/Triple Warmer Tap

Another part of the Triple Warmer pathway, this one on the back of your hands, can be stimulated to manage anxiety and fear. Holding your hand over your Heart Chakra and tapping Triple Warmer back into balance:

- Bring to mind yet another situation where you “lost it” with your partner.

- Put one hand over the middle of your chest (this is your Heart Chakra), and find the V between your ring finger and little finger on the back of that hand.

- Below the V is a ridge. Tap inside this ridge with the four fingers of your other hand (see Figure 5-3).

- Finally have both hands resting over your Heart Chakra as you end with the words, “I am safe!”

Tapping on the ridge of the hand that is over your Heart Chakra can also provide quick emotional first aid any time you are feeling anxious or afraid.

These three simple energy techniques, individually (selecting the one that seems to work best for you) or in combination, can be used to desensitize Triple Warmer to interpersonal situations that have tended to hook you.26 As you shift the energies that maintain fear-based reactions, you are opening a door for changing them. Additional techniques presented in the following two chapters focus on healing the residue of difficult childhood experiences and transforming the emotional and behavioral patterns that arose from them. These techniques involve the stimulation of acupuncture points while bringing specific memories or visualizations to mind, and they can laser into the energies of attachment. You will begin to get a feel for how this is accomplished in the three case histories presented during the following discussion.

FIGURE 5-3 Heart Chakr/Triple Warmer Tap

Soothing Yourself, Managing Your Emotions, and Repairing Ruptures

While it is beyond the scope of any book to be a substitute for psychotherapy or for interactions with a partner that heal childhood attachment wounds, you can do a great deal to enhance your relationship by using techniques that shift the energetic underpinnings of attachment difficulties.

Three basic skill sets that promote secure attachment—soothing yourself, managing your emotions, and repairing ruptures within an intimate partnership—were ideally learned early in life during daily interactions with your primary caregivers. Where you have gaps in these skills, your primary relationships are directly impacted. But it is not like signs are imprinted on our foreheads as we grow up that say “deficits in self-soothing ability” or “poor manager of emotions” or “anxious about intimacy.” We develop our skill sets for self-soothing, emotional management, and relating intimately to the extent that we do (or that we don’t), and we try to make the best of what we have. What might have been theoretically possible is not on our radar. It is not part of our living reality. Donna’s orienting her early life around the theme of not causing trouble made her very good at self-soothing but not as practiced in getting what she needed from her closest relationships, an essential skill for thriving in an intimate partnership. Conscious choice, however, was not involved. If she had a need that would cause any inconvenience for her partner, it did not occur to her to express it and risk being trouble for him.

Can we improve our relationship patterns by further developing and refining these skill sets? For each, we will present some of the basics and describe a person who made a significant positive shift using the energy psychology techniques you will be learning in the following two chapters.

Self-Soothing

Since infants aren’t equipped with the ability to soothe themselves when they feel distressed, but only to cry out, they depend on their caregivers to provide comfort. From the responses they receive, they acquire strategies for coping with distressful emotions or difficult experiences. Adults who haven’t developed adequate skills for self-soothing tend to become overly reliant on their partner for emotional comfort and resentful when it is not provided.

Skills for improving your mood and bringing calm, nurturing, and pleasure can be learned at any point in your life. They are generally quite basic, relying on your senses. A hot bath is one of Donna’s favorites. We both like to take walks in beautiful natural settings. Energy techniques such as those presented here are always in our tool kit. Music, dance, art, sports, and meditation are other popular forms of self-soothing. Simple enough. Readily available. Often free or almost free. But for people who didn’t learn in their formative years that they can make themselves feel better, calmer, or more relaxed, times of distress can lead to an internal panic and often a clutching toward others or an escape into drugs, junk food, or other addictions. It does not occur to them that they can take simple, healthy steps that will help them feel better.

Elizabeth, at thirty-one, frequently felt rebuffed, disregarded, and unloved. While her husband demonstrated his love for her in many ways and was always trying to comfort her, she was, at these times, inconsolable. To make it worse, after these episodes she would withdraw from him further because, despite his sincere efforts, she felt he hadn’t been there for her. Self-soothing wasn’t even in her repertoire as she would ruminate on how she had been wronged and sank ever deeper into a dark hole of despair. Not only hadn’t Elizabeth learned much about self-soothing as a child, you might wonder how she managed to make it into her thirties so unskilled about helping herself feel better during times of emotional distress.

Unfortunately, this type of lapse is not particularly unusual. While many people pick up new skills for self-soothing as they mature, others face internal obstacles that prevent them from learning and using even the most obvious self-soothing skills. So rather than simply trying to teach them techniques for self-soothing, these internal obstacles also need to be addressed.

A theme in Elizabeth’s bouts of feeling unloved was that someone else always seemed to be receiving the credit and recognition that she deserved. At another level, however, she felt undeserving of the very recognition she desired and expected. This was particularly evident in her inability to accept compliments even after she had done something extremely well. Rather, she would find flaws in her actions that no one else would even notice and relentlessly beat herself up for them. Obsessing about her own flaws and sinking into her resentment of those who she felt had wronged her consumed her so completely that doing things that might make her feel better simply did not come into her mind.

Derived from the field of energy psychology, the protocol used with Elizabeth (which you will be learning in chapters 6 and 7) includes two basic steps. The first involves giving a zero-to-ten rating on the level of distress or discomfort you feel in relation to an issue you wish to change. The second is to stimulate a set of acupuncture points by tapping on them while keeping the issue active in your mind. This simple combination is proving to be extraordinarily powerful in rewiring the neural pathways that underlie a range of emotional difficulties.

Elizabeth’s initial rounds of tapping focused on the fierce judgments she would place on herself, which she had rated as being at a 10 in relation to the amount of distress she felt when thinking about them. What emerged as she continued to tap were childhood memories of longing for her father’s approval, which she never received (as she remembered it), yet when her younger brother was born, he got the praise and adoration she so desperately craved. Tapping on her pain about this started a healing process that went very deep. She was eventually able to recognize and tap on the exaggerated authority she was still giving her father to determine her sense of worth. In a subsequent session, she focused on and neutralized her emotional response to specific, recent incidents where she had judged herself harshly and was unable to accept sincere compliments about things others felt she had done well.

By the time she’d made some progress with these issues, the tapping was able to directly address self-soothing. A mental association was made by using energy techniques to link times of feeling despondent with doing activities that consoled her (e.g., “Even though there may still be times that I feel down, I know I will feel better if I sit on the porch and listen to Enya”). Not only did the episodes of struggling with her self-worth become much less intense and less frequent, but it now occurred to her when they did happen that she could take positive steps that would bring her comfort and relief. Finally, she was given instruction in four ways to “put money in the bank” so her reserves would already be stronger at times she needed self-soothing. These were simple physical or interpersonal actions that were in her control: enough sleep, enough exercise, enough physical touch, and enough emotional contact.

Learning to self-soothe had an enormous impact on Elizabeth’s marriage. She no longer would desperately look to her husband to make her feel better or rage at him when he couldn’t. By having a way to amp down to a manageable level the intensity when she was feeling bad, she was also able to let her husband help her. Now that his overtures of support could be received when they were needed, what had been a thorny obstacle to their being close to one another became a source of bonding.

Emotional Self-Management

The second skill set that grows out of your early attachment experiences is the ability to manage your emotions. More than a hundred human emotions have been identified,27 with most of them being combinations of or the social shaping of a few basic emotions found in people of all cultures, such as anger, fear, sadness, disgust, surprise, anticipation, trust, and joy.28 The English word emotion is derived from the Old French esmovoir, meaning “to excite.” While psychologists define this basic concept in numerous ways, all would agree that emotions involve arousal (“to excite”) and that they influence the way we process our thoughts and experiences.

At the most basic level, in the life of an infant, an internal event (such as hunger or feeling cold) or an external event (such as a warm blanket or a loud sound), results in simple appraisals: “this is good” or “this is bad.” While this is the prototype for the more nuanced emotions that will come later, this basic assessment of good or bad, Daniel Siegel explains, “prepares the brain and the rest of the body for action.”29

The parents’ responses to the infant’s expressions of positively toned or negatively toned arousal lay down the neural pathways that help children learn to regulate their own nervous systems. You figured out how to manage your “states of arousal and inner processing”30 through those early interactions. If your parents’ responses to you were attuned to your internal experiences, you were likely to form a secure foundation for navigating through life with confidence about the validity of your feelings and thoughts. If your early caregivers usually failed to validate your internal experiences in their moment-to-moment exchanges with you, your foundation for trusting your feelings and thoughts as valid guides became shaky. If this lack of attunement is extreme, as in cases of abusive, emotionally disturbed, or severely neglectful parents, children are set on their journey through life with a compass that is fundamentally flawed. They may find themselves regularly pushing down the truth of their emotions and experiences, distorting them, or becoming overwhelmed by them.

Early caregivers not only validate or fail to validate the child’s internal experiences, they also model for the child how to respond when others express their emotions. A parent whose internal state is dominated by fear or anger simultaneously evokes fear or anger in the child and also, through reinforcement, teaches the child specific ways of responding to fear or anger. A girl may take it upon herself to give a fearful mother the support she herself really needs from that mother, or try to make herself invisible in the presence of an angry father. These patterns tend to carry over into her adult relationships even when they no longer fit.

Individual childhood experiences involving trauma, severe loss, or other emotionally intense experiences, if they are not adequately processed, can also lead to patterns of emotional response that are not appropriate to the current situation. In Parenting from the Inside Out, Siegel and Mary Hartzell identify two basic types of responses to emotionally challenging situations: the “high road” and the “low road.”31 The high road is dominated by advanced brain structures that came later in evolution and sit “higher,” toward the top of the head, in the cerebral cortex. The low road is dominated by brain structures that sit below the cerebral cortex, including the amygdala, and that govern automatic behaviors such as the fight/flight/freeze response. When you are on the “high road,” your responses are well considered, flexible, and appropriate to the situation. When you are overly stressed or in a situation that otherwise triggers you into the “low road” state of mind, which includes being trapped in your Energetic Stress Style, you may be flooded by intense emotions such as fear, sadness, or rage, leading to “knee-jerk reactions instead of thoughtful responses.”32

We have all experienced “low road” behaviors from both sides—we’ve received them and we’ve acted them out. Unresolved childhood issues make us more susceptible to these storms of difficult feelings and inappropriate actions. When “low road” responses occur, and particularly when they repeat themselves, notice what triggers them. If you can’t identify the triggers, your partner probably can. You can then use the energy psychology approach presented in chapters 6 and 7 to defuse these emotional triggers.

Sometimes, however, this requires more than just focusing on the trigger. You saw how, in order to learn self-soothing, Elizabeth had to first overcome emotional obstacles rooted in earlier experiences. A seminar on self-soothing wasn’t going to be very useful to her until these interfering issues had been resolved. Learning how to manage intense emotions also often requires a focus on unresolved issues from the past. Fortunately, as you work with the behaviors you want to change, earlier experiences that are at their root often come into your awareness, making them accessible for healing using the energy psychology protocol you will be learning.

For example, a successful medical technology executive named Raul would become furious when younger associates disagreed with him, even if the disagreements were trivial. While in most situations he had a very sweet disposition, this pattern was also carrying into his marriage and his relationship with his children. It was clear to him that his outbursts were hurtful to everyone, including himself, but he was failing to prevent them despite his resolve to do so. Tapping on recent incidents and imagined situations that might trigger him lowered the intensity he felt to a degree, but it could be no match for these deeply ingrained behaviors until their roots were being addressed.

Raul’s father, a physician, was very stern with his three sons and imposed his will on them with criticism and rage. Raul was chagrined to realize that he had, in terms of those traits, become a carbon copy of his father. Imprints from such emotional models do not change easily, but over several energy psychology sessions, significant shifts occurred. The tapping focused on images of his enraged father, the feelings they brought up in him, and the thoughts and conclusions he came to as a result of these experiences. Each childhood experience involving anger that he could recall was addressed using the tapping. With these earlier experiences revisited and emotionally reworked, the triggers in his current life were easily brought down to zero on the zero-to-ten scale, and he found himself able to stay on the “high road” when these same triggers presented themselves. The neural pathways maintaining the old pattern had shifted, and managing his anger was now rarely a problem (yes, we are trying to get you excited for the energy psychology instructions in the following chapter).

Repairing Ruptures

To thrive, we need both intimate contact and alone time. Most ongoing relationships provide ample opportunity for both. They are composed of an unending series of separations and reconnections, part of the ebb and flow of daily life. If your parents gave you space for solitude and were then available when you needed connection again, you are already practiced in the dance of coming and going. More challenging for everyone, however, are separations that are experienced not just as a temporary time apart but as a rupture.

With children as well as adults, the consequences of a rupture depend more on whether, how, and how quickly the rupture is repaired than on its nature. How to repair the unavoidable ruptures that occurred as you were growing up was modeled (and in other ways taught to you) by your parents. In some families, ruptures are ignored as much as possible. You are supposed to “get over it” and just go on. In others, resentments are built and harbored. These strategies tend to echo into the person’s adult relationships.

Families that are effective at repairing the inevitable ruptures among their members feel safer, produce children who are happier and more emotionally secure, and meet life’s challenges with greater ease and flexibility. To repair a rupture, you first need to bring yourself from the “low road” of mental functioning back to the “high road.” Siegel and Hartzell suggest steps that will be familiar to you as elements of your STAR Pact (chapter 3), including a temporary separation (the Pact’s “Stop”), physical activity (the Pact’s “Tap” and other energy techniques), empathically stepping into the other’s experience (the Pact’s “Attune”), and finally reengaging (the Pact’s “Resolve”).33

Vern and Gloria rarely argued. Whenever they had differences, Vern would quickly tune into Gloria’s position and take it as his own. If this was not possible and a rupture between them did occur, Vern would be disheartened, certain it was his fault, and feel full of shame as he tried to grovel his way back into Gloria’s good graces. While having a spouse who is so eager to agree with you might seem desirable, it was Gloria who brought them into therapy. Although the peace and easy flow they enjoyed in their first two years together had been a relief in comparison to her other relationships, by their fourth year it was seeming to her that she was with a caricature of a real person instead of someone who brought his own feelings, thoughts, and opinions into the relationship.

Vern’s parents had minimized or made light of their differences rather than acknowledging and resolving conflicts, a workable if not ideal strategy, discussed in Chapter 1 as that of the Avoidant couple. A product of his past, Vern brought this style to his relationship with Gloria. But for Gloria, emotional engagement was a vital aspect of a relationship, and all Vern’s agreeableness only left her feeling lonely. True to form, Vern agreed to Gloria’s suggestion that they enter therapy to change his basic way of relating.

Just as you saw with Elizabeth and Raul, work that began with a stated concern quickly shifted to childhood experiences. Vern recounted the way he was witness to unspoken tension between his parents on a myriad of issues, from dinner choices to which car to buy. With little discussion, his mother’s preferences would generally carry the decision, but expressions of his father’s resentment and his mother’s guilt, which couldn’t be concealed, were prominent in Vern’s memory.

Vern used the acupuncture point tapping protocol while focusing on those memories, on his shame about not being able to do a thing about the tension in his family, and on his reluctance to introduce any tension into his marriage. While his zero-to-ten rating rapidly went down in relation to his past, it would not go below 5 as he focused on his being more forthcoming with his preferences in the marriage. He was clearly ambivalent about that objective.

As Vern explored his ambivalence, it became clear that he had dire misgivings about what would happen if he ever took a strong stand that challenged Gloria’s position on virtually any matter. One big reason for this, it turned out, was that he had no idea of how to repair a relationship rupture since he was so inexperienced with them. He imagined, instead, that it would spread like a wildfire until the marriage had been destroyed. In the safety of the therapy office, he was able to tell Gloria clearly and firmly that he felt she was being much too strict with their adolescent daughter. This triggered Gloria into a strong defensive reaction. She was proud of her parenting skills and thought her husband appreciated and fully supported them. Hearing that he didn’t shocked her and flooded her with feelings that brought her onto what we have been calling the “low road.” She was deeply hurt, felt betrayed that Vern had given her no clue, and was soon ruminating about all the other areas where he might be secretly judging her. She also let him know, with escalating volume, how absurdly wrong he was in the beliefs about child-rearing he was expressing.

It suddenly seemed as if Vern’s fears had been well taken and that if they ever got through this therapy-induced mess, he should keep his opinions to himself forever after. Gloria was completely unaware that she was fulfilling Vern’s catastrophic expectations about doing exactly what she was asking him to do. I (David) was, at that moment, reflecting on the dubious wisdom of having chosen a profession that messes with a family’s established adaptations. But I also knew that this was an opportunity for them to have the experience of repairing a relationship rupture. I took them through the steps of the Pact. By the end, Gloria was back on the “high road” and we were all laughing about the ironies that had just played out. Vern had had the experience that even one of the worst reactions he could imagine to his having stated a disagreement had been repaired within half an hour.

During the week following the session, they had numerous deep and creative discussions about discipline for their kids and were feeling closer to one another than they had for a long time. In the next session, with Vern now having a sense that ruptures could be repaired instead of being something to be avoided at all costs, additional acupuncture point tapping dissolved his knee-jerk discomfort about stating a disagreement to Gloria. Being able to tolerate ruptures and repair them were essential skills in Vern’s ability to take a next step in the evolution of his marriage.

The three skill sets discussed in this section—self-soothing, emotional self-management, and being able to repair ruptures within an intimate partnership—are laid down in our family of origin and early interactions with our caregivers. But they are skills that we can continue to develop and refine throughout our lives. Particularly in the crucible of our intimate partnerships, we discover the shortcomings of the strategies we have brought forth from childhood. The cases described here illustrate breakdowns in these three core relationship skill sets. Each was quite challenging—but not particularly unusual. We hope this discussion has provided a context for recognizing your own strengths with these skills as well as for assessing areas where they may need attention, along with instructive models. Healthier attachment in your most intimate relationships is a reward well worth striving toward.

On to Chapter 6

As you saw with Elizabeth, Raul, and Vern and Gloria, tapping on acupuncture points—the core physical procedure in energy psychology—can be applied to overcoming lapses in your relationship skills while strengthening the foundation of your bond. These focused efforts can also help with many other aspects of your relationship and, not just incidentally, with your own personal evolution as well. Chapter 6 introduces you to the basic steps of a simple but powerful energy psychology protocol.