Church Is Where the Music Is

YOGA IS LIKE A MIGHTY RIVER with multiple tributaries that flow into, fill, and inform it. Hatha yoga, the yoga of the physical body, with its shared focus on sensation, breath, and energetic flow, is the branch of the river that has rightly become so popular in the West as it directly addresses our culture’s urgent need to awaken the body and heal the ill effects of somatophobia. It’s not, however, the only branch of yoga. Jnana yoga works directly with the mind and is not all that dissimilar from many traditional Buddhist practices. Karma yoga, the yoga of service, encourages selfless kindness directed toward others who may need our help and assistance and serves as a model for ethical behavior in the world. Raja yoga is a synthesis of the other branches, combining physical asanas, breathing practices, ethical behavior, and meditation. Tantra yoga, sometimes practiced individually and other times with a partner, employs a number of physical practices designed to liberate the orgasmic energies at the very core of the body. Bhakti yoga, the yoga of devotion, opens the heart through the power of music.

Bhakti yoga is mostly known today through the singing of traditional Indian bhajans—devotional songs whose lyrics are sometimes composed entirely of a single mantra or phrase, and are most often sung at gatherings where people come together to chant and sing. But the original bhakti yoga was a path of spiritual awakening, explored on a daily basis not in groups but by individual yogis, which was based solely on the effect that sound has on the human body and mind.

Long before the Greeks developed the modes, or scales, that would become the foundation of all Western music, bhakti yogis were exploring these same scales as a source of awakening the sensations and energies of the body. It’s not known whether Pythagoras, viewed as the Western discoverer of the mathematical basis of the notes of the scales, knew of the bhakti tradition or not. But like the bhakti yogis, he believed that the purity of the notes when properly struck or intoned could heal the body and cleanse the mind.

The Indian classical music tradition took the scales of bhakti yoga and developed them into a high art form in which the individual musician would spend decades of disciplined training in order to perfect her voice or master his instrument. However, while this tradition grew directly out of bhakti yoga, the original bhakti yoga was geared entirely toward personal awakening, not accomplished performance. The bhakti yogis, spending long years in practice, valued the purity of the scales and notes not so much because they created an enchantingly beautiful sound that others might enjoy, but rather because the sounds affected them directly and personally. For bhakti yogis, the only audience that matters is themselves.

Bhakti yogis would awaken in the morning and, while their hatha brothers and sisters would begin their breathing practices and asanas, they would tune their tamboura—the classical Indian stringed drone instrument whose tuning forms the basis for all the many different scales. They would then begin singing the notes of the scales: sa, re, ga, ma, pa, dha, ni, sa (the Indian equivalent of do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, ti, do). Singing the individual notes of the scales creates a vibratory resonance that, while generated most prominently in the area of the throat, can be felt to spread in waves throughout the entire body, not unlike the ripples caused by a pebble dropped into a still pond. If you played a wind or stringed instrument, every day you would bathe yourself—from the outside in—in the vibrational healing of the sounds you were creating.

When I was in my early twenties, I lived and studied in San Francisco with P. D. Shah, a master of the rudra vina of north India. The rudra vina is one of the earliest Vedic stringed instruments, several thousand years old, and it is essentially a sound chamber that you enter into while striking the strings. It is a rare instrument, especially today, and one look at it is enough to tell you why. To call it unwieldy is an understatement. At either end of the instrument is an enormous gourd, each the size of a large pumpkin, which form the two sound chambers. These are connected to the ends of a five-foot shaft of bamboo that sits on top of the gourds. Frets secured by wax are attached to the top of the bamboo, and strings are stretched over the top of the frets for the musician to produce the individual notes. Additional strings are stretched along the side of the bamboo to create the drone sound that forms the foundation over which the individual notes weave their spell.

To play the rudra vina, you sit down in cross-legged meditation posture, set the large gourd on the right side of the instrument on your right knee, and place the left gourd high on your left shoulder, next to your ear, where the sounds you create are magnified and projected directly into the body. It’s an armful, for sure, but the deep, visceral sounds of the vina, amplified through the close proximity to the gourds, penetrate directly and powerfully into the body. The sounds that the vina produces are long and low, and the music is slow and deep. When you play the vina, you feel it as much as hear it. The individually struck notes last for a long time, and the music is in no hurry to go anywhere. A student of the great sitar player Ravi Shankar once asked my teacher, “How fast can you play on the vina?” My teacher simply replied, “How slow can you play on the sitar?” The purpose of the music is not to dazzle but to awaken.

The beenkars, as the players of the rudra vina were called, were yogis, not performers. Their devotion to their instrument was for the purpose of awakening the body’s dormant energy centers (known as chakras), not for entertainment. My teacher would tell me how, in his younger years, when he was first learning how to play, it was not uncommon for him to practice ten hours a day for months at a time. Even in ancient India, beenkars were a rare breed and were often some of the most valued members of a maharaja’s court. They would be given a small cottage on the palace grounds, have all their basic needs cared for, and would be asked to come and play at court perhaps only once a year.

As a young man, my teacher was welcomed into the court of the equally young Maharaja of Jamnagar and quickly entered into a close personal friendship with him. The maharaja didn’t want to be just my teacher’s patron and friend. He wanted to be his student as well and learn to play the vina himself. So, in a lifestyle reminiscent of stories of some contemporary rock ’n’ roll bands, my teacher would wake from sleep late in the afternoon, he would walk over to the palace where the maharaja would greet him, food and drink would be served, and they would play the vina throughout the night, not retiring to their residences to sleep until the sun had come up. My teacher would regale me with these stories long into the night. It was a lifestyle that held a great deal of fascination for me as a young man.

It wasn’t just food and drink that would be provided for the musicians, teacher, and student during the long nights at the palace. A hookah filled with Shiva’s sacrament would be present, and indulged in, all through the night as well. Cannabis and music—especially music that is improvised and makes the body want to come alive—have been the easiest of bedfellows down through the ages, even up to the present day. The sweet fragrance of pot smoke hangs plentifully in the air, both onstage and in the crowds, at reggae concerts, rock ’n’ roll shows, electronic music gatherings—wherever music that is directed more toward the body than the mind is played and shared. Here in the West, the link between cannabis and music began with the blues players of the Mississippi Delta and the early jazz musicians from New Orleans. Mezz Mezzrow, a white clarinet player from the 1930s and ’40s, who was also a gifted writer, has written about the evening that he went to his club and one of his black brothers came up to him and said, “Mezz, take a toke of this.” He immediately did, went out and played music like nothing he’d ever played before, and was a cannabis devotee ever after. Musicians such as the Grateful Dead, Louis Armstrong, Willie Nelson, and Snoop Dogg have openly advocated for how cannabis fuels the fires of their musical creativity.

My teacher essentially spent two years of his life invoking Shiva all through the night, and he would say that it was during this period that his music exploded onto a whole different level of creativity and expression. He would speak to me about how the music, through the creation of what he called the One Sound, led to a direct experience of Shiva’s realm of realization. Furthermore, he told me of how Rudra and Shiva are so closely associated, and often even identified with each other. Rudra lived at a time before Shiva, but evidently shared many of the same characteristics. To invoke Rudra, my teacher would tell me, is to invoke Shiva. For him, the music of the rudra vina was Shiva’s music as well.

He would also tell me that the primary purpose of bhakti yoga was to simulate the One Sound, the hum of the universe, and align the vibratory nature of your individual body with the resonance of this sound. In this way you could, through your music, merge your feeling body and dissolve your individual sense of self into the vastness of the One Sound. But what about the individual notes, I would ask him? The individual notes, he would respond, are simply variations in pitch of the One Sound. It was an explanation that made sense as the music clearly had the ability to stimulate the feeling presence of the body.

While we were living together we would spend a great deal of time singing the notes in the different scales as a way to learn them. He would say that playing the vina created an environment of healing sound vibrations that would affect the body from the outside in, while singing the scales would awaken the body from the inside out. I no longer play the vina; it quickly became apparent that to do this instrument any justice at all I would need to devote my life to learning it, forgoing any interest in anything else at all, and that was not a commitment I could see myself making. But those scales got into my bones, and I continue to sing them and feel how they affect and stimulate the vibratory sensations and energy centers of my body.

Opening your voice and singing the scales while listening to the drone of an electronic tamboura is one of the most potent practices to awaken the body and illuminate the mind that a lover of Shiva’s sacrament can explore. And it’s far easier than you may be thinking right now. In fact, for those of you (which means a great many of us) who were told at a young age that “you don’t have a good voice” or that “you can’t sing,” this practice is a wonderful opportunity to debunk that lie, which only serves to secure the limiting holding pattern of somatophobia. Everybody can sing, just as everybody can breathe.

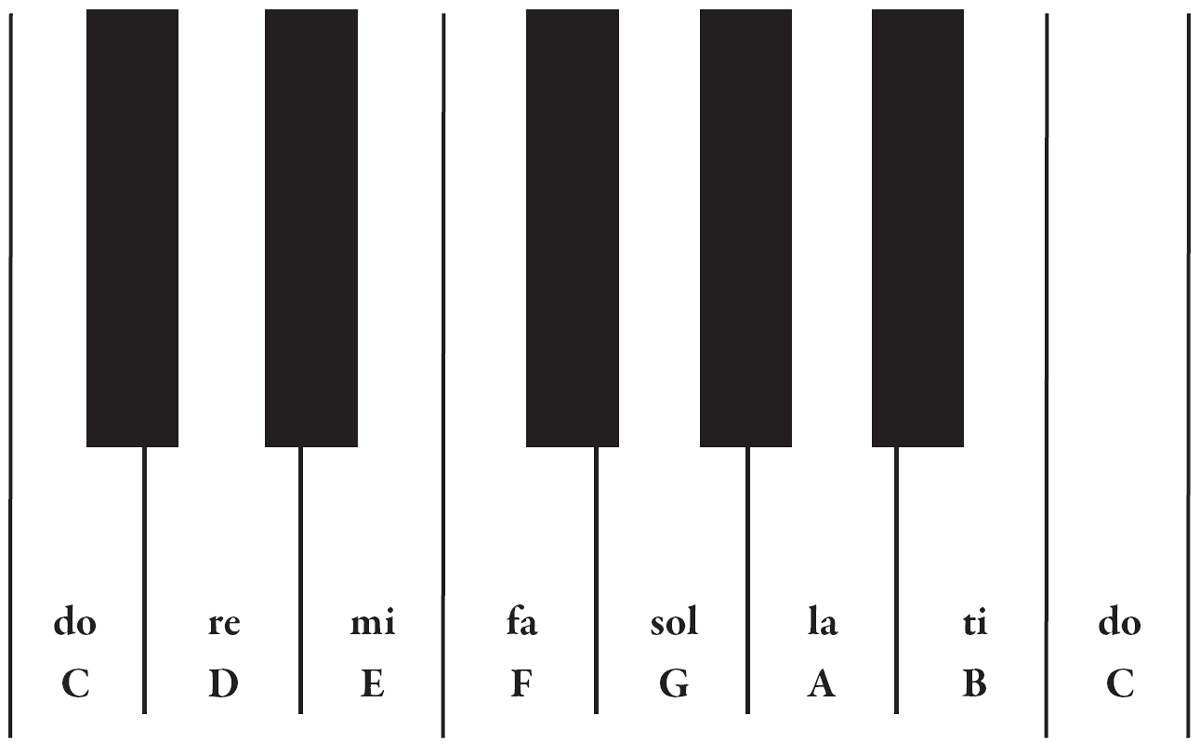

Let’s begin by taking a look at the white and black notes of a piano keyboard:

The white and black notes of a piano keyboard.

These are the notes that you find on the piano, starting with middle C on the left and going through an entire scale, ending with C an octave higher on the right. You will see that there are eight white keys and five black ones, which makes for thirteen possible notes from one octave to the next. But every scale only has eight notes in it, which means that there are numerous possibilities to create different scales out of the thirteen possible notes.

In practice, the permutations of possible scales are minimized by the fact that every different scale in north Indian music always has the first note, called the tonic (in our example, the C at the left of the image), the fifth note (in the example shown here, the G), and the eighth note, the upper octave of the tonic (the C at the right of the image). These three notes, when played together, form the sound of the tamboura, the drone instrument that is always played underneath each and every scale. The sound of these three notes together is extraordinarily pleasant and centering. Played together, they form the musical basis of the One Sound.

But then the other notes of the scale are added, and the beauty of the One Sound is embellished. The sound of the drone may be likened to the ocean, and the melodies that can be created from the individual notes of the scale are like flying fish skipping across the surface of the ocean in limitless patterns of motion. Both ocean and fish are equally necessary to create the music that will open and awaken the body.

If you were to strike the white notes in sequence, you will immediately recognize the major scale of Western music: bright, happy, and cheerful. But if you start creating scales that use some of the black keys, the mood and quality of the scale change dramatically.

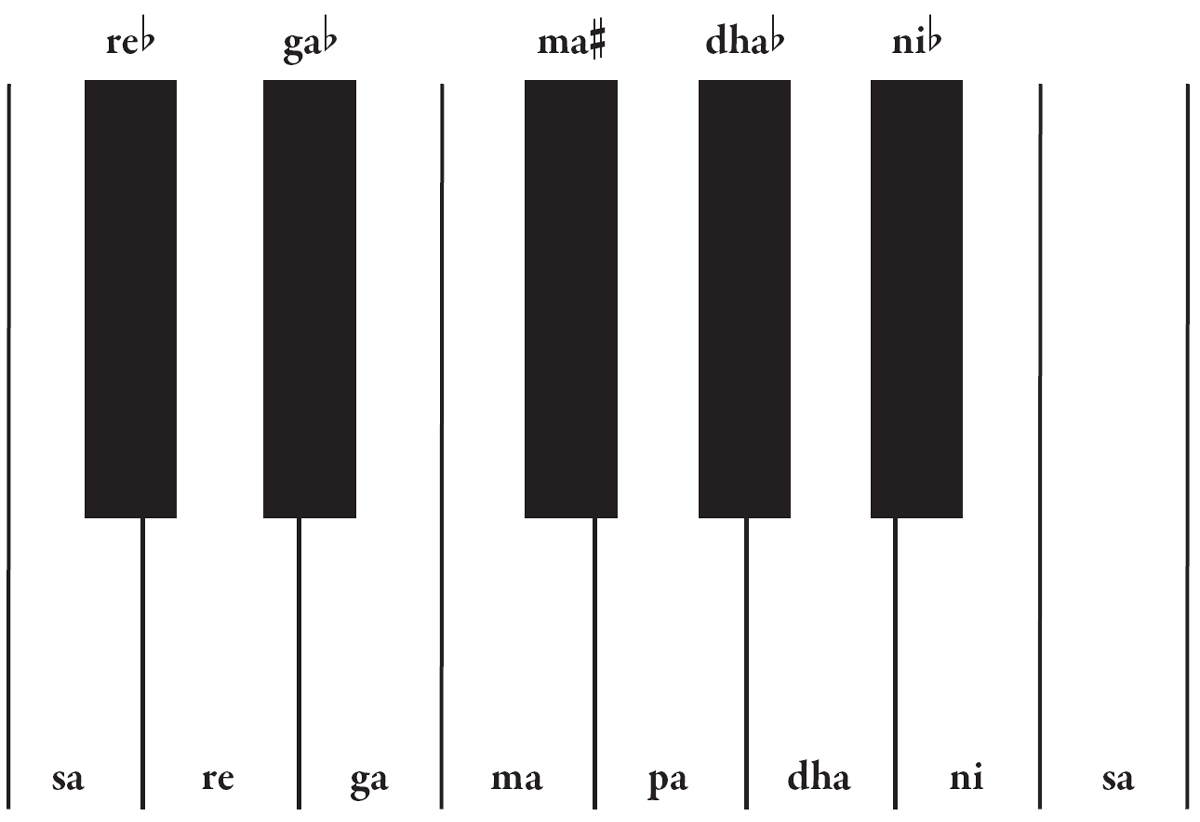

Instead of the alphabet names for the notes, you can also sing the major scale with the common Western words do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, ti, do, or the north Indian names sa, re, ga, ma, pa, dha, ni, sa. The words may be different but, in the case of a scale starting at C, each correspond to C, D, E, F, G, A, B. Let’s look at our piano diagram again with this new annotation applied to the keys (see page 104).

The first thing to notice is that the two sas and the pa are never flattened or sharped, and this is because these three notes appear in every scale as the foundational sound of the drone. Ancient Vedic music is based on what are called the parent scales, which simply means that all the music that can be played derives from these scales. There are only six of these scales, each corresponding to one of the modes that were developed later by the Greeks, and when you look at the progression from scale to scale you’ll notice that one scale proceeds to the next by flattening an additional note. For example, flatten the sharpened maof the first scale Kalyan, and you get the natural ma of Bilaval. Flatten the ni in Bilaval, and the scale becomes Khamaj. Flatten the ga in Khamaj, and you get Kafi. Flatten the dha in Kafi, and you create Asavari. Flatten the re in Asavari, and you get Bhairavi:

Piano keys with Indian names for the notes.

Kalyan: sa re ga ma♯ pa dha ni sa

Bilaval: sa re ga ma pa dha ni♭ sa

Khamaj: sa re ga ma pa dha ni♭ sa

Kafi: sa re ga♭ ma pa dha ni♭ sa

Asavari: sa re ga♭ ma pa dha♭ ni♭ sa

Bhairavi: sa re♭ ga♭ ma pa dha♭ ni♭ sa

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Mogul rulers of India brought with them their own traditions of modal music that were added to the parent scales, so when you start exploring singing the notes in these scales, you might want to add the following exotically beautiful scale as well:

Bhairav: sa re♭ ga ma pa dha♭ ni sa

As you start exploring these scales, you will see that they each reflect a very different mood. Kalyan is dreamy. Bilaval is the cheerful major scale that we’re so familiar with in Western music. Khamaj starts getting smokier and is often heard in folk rock music. Kafi gets smokier still and forms the basis for Western blues. Asavari is mysterious, simultaneously dark and gorgeous. Bhairavi is the darkest of the scales, reminiscent of pensive walks in the middle of the night. Bhairav mixes both major and minor sounding scales and is both shadowy and hopeful.

To become a hatha yoga student, you’ll need to purchase a sticky mat on which to explore your asanas. To practice sitting meditation, you’ll want to purchase pillows or a kneeling bench and a supportive mat to rest them on. To enter into the practice of the One Sound, you’ll want to purchase an electronic tamboura.

The sound quality of electronic tambouras has become far more sophisticated in recent years, and I encourage you to purchase the best quality tamboura you can afford. Even the most expensive ones are far less costly than the traditional handmade tambouras that connect a long, hollow shaft of wood to a resonating vegetable gourd over which the individual strings that you need to tune and pluck are strung. If you become besotted with the practice of the One Sound, you may eventually want to play an authentic tamboura, but an electronic tamboura is a wonderfully versatile instrument with a good sound and an attractive price. You can tune it to any tonic note and, with more elaborate models, you can even add other notes from the scale you’re singing. A variety of quality electronic tamboura can be purchased through online retailers. You may also be able to find them at select stores that specialize in non-Western musical instruments.

Entering into the One Sound*10

Bom, Shiva!

I tune or turn on my tamboura

and begin by silently listening to the sequence

of the following four notes:

pa high-sa high-sa low-sa,

the sound of Shiva,

like a blissful alarm on a clock

that starts waking me up

to the highest potential

of my body and mind.

After a while I start

by singing the lowest sa,

the first tonic note of the scale,

finding the exact pitch of the note

that resonates with the sound of the tamboura.

Sometimes I hum sa

with my mouth closed,

feeling the vibrations

spread through my body.

Sometimes I sing sa

with my mouth open,

surrendering to the sound

that wants to come through me,

not holding back.

Only when I feel the resonance

between the perfectly pitched sa

and the tamboura that it melds with,

might I begin to explore other notes in the scale.

I move to re

and sing re until I feel the perfect resonance

between the re I’m singing

and the tamboura underneath.

In this way I start to move

through all the different notes of the scale,

hearing and feeling how each note

creates a glorious chord when combined

with the foundational notes of the tamboura.

As I become increasingly familiar

with the different scales

and their different notes,

I can start to let go,

move, and jump

backward and forward

between the notes of the scale,

no longer just singing them

as a linear scale, up and down.

Simple melodies start to appear,

spontaneously,

and my song starts singing itself.

No one can sing this song but me.

In the presence of this sound

sensations start flooding my body

and get drawn into the sound

like iron filings to a magnet.

In the presence of this sound

mind starts shutting itself off.

I sing.

I let go.

And over time

I lose myself in the One Sound.

Sing for as long as you like or as little as you like. Every note you sing will eventually find its way to the exact pitch that resonates with the sound of the tamboura. Once you feel this resonance, you know you’ve found your note. I once knew a bhakti yogi who would tune his tamboura and sing sa every morning for an entire hour. No hatha yoga. No meditation. Just the opening of his voice to the One Sound that melds seamlessly with the sound of the tamboura.

Feel how the sound stimulates sensations through the entire body, how it wakes the entire body up, how everything begins to vibrate, how the feeling presence of the body starts to shimmer. Hold the notes as long as you can, the sound riding on your breath. So often, when we exhale, only a fraction of the stale air leaves our lungs. One of the real bonuses of singing your version of Shiva’s song—which will never be the same from day to day, just as Shiva’s dance will never be the same from day to day—is that it lengthens every exhalation you take. Removing all the carbon dioxide from your lungs through a long, complete exhalation lowers the acidity of the blood, making the entire system more alkaline. The less acidic and more alkaline you are, the healthier your body will be.

Church is where the music is. It’s always been there, and it always will be. We take the contemporary ubiquity of music so for granted that we forget that in a world not long ago—before cell phones and mp3 players, before CDs, cassette tapes, and LP records, before radio started being broadcast into our homes—music was a sublime rarity. It was mostly heard only if you created the sounds yourself or attended a religious service in a house of worship: Gregorian chant, the singing of Jewish cantors, the muezzin’s call to prayer, the earthshaking sound of a grand pipe organ, and the ecstatic hymns of bhakti mystics and Southern Baptists alike.

The I Ching tells us that “music has power to ease tension within the heart and to loosen the grip of obscure emotions.” This healing power is the action of real religion, and music is one of its most reliable actors, promoting a gospel of easing tension, loosening emotional holding, and breaking through to the sublime, and this is happening today as much on our city streets and in our dance clubs as in our more traditional houses of worship.

Joshua is described as having brought down the walls of Jericho with sound alone. (They may have been real walls; they are certainly, metaphorically, the walls encasing our hearts.) Young people dance together all night long at raves, their bodies reverberating to the sounds of drum and bass instead of a pipe organ. The most sacred mass gathering I ever attended was my very first Grateful Dead show in 1969, at which I and everyone else in the audience became dancers in a single moment of exaltation.

Many years ago, while visiting Malaysia, I saw a young man sporting a T-shirt that proclaimed “Music Is the Weapon of the Future.” The music that is so incessantly broadcast around the world today makes our bodies want to move, and it’s going to be increasingly difficult to force-feed stale and hateful dogma to a young person whose body has connected with its impulse to move, to dance, to express itself with joy. So let’s all enlist as soldiers in this musical army of peace, bombarding the world not with weapons of destruction but with weapons that melt and dissolve hatred, creating healing in ourselves and others through every note we hear and sing, giving our bodies permission to move whether we’re responding to the ear-shattering beats in a club or the subtle rhythm of the breath as we sit on our meditation cushion.