Chapter 2

Men and women (overconfidence)

Most people have a lack of respect for economists. This partly derives from the basic assumption that underlies classical economic theory. The world that economists study is very complicated. The modern economy has a great number of moving parts, each of which interacts with the others. So there are a huge number of relationships to deal with. Moreover, these relationships change dynamically over time. Economists still struggle even to come close to building an accurate and complete model for how a modern economy operates, let alone have the computational power to run such a model to try to predict what will happen if we change some policy or other.

In order to try to understand the economy at a minimally useful level, classical economic theory was based on an assumption that mankind was totally rational in every decision made. Economic theory assumed that, when faced with a decision, we have all the facts, can weigh them up accurately and will always make a rational choice that maximises the (usually monetary) value to us. This led to the development of useful theories about how the economy worked.

However, anyone who has ever thought for a moment or two about what people actually do, and what they themselves actually do, will realise that these assumptions were bound to limit the usefulness of these theories. They were useful as far as they went, but they were not looking at the real world. We rarely have all the information. We have great difficulty weighing up all the issues. We most definitely do not act perfectly rationally every time. We all make some decisions impulsively and emotionally. We are all prone to cognitive biases, and we often make our most important decisions in a less than optimal manner.

In recent decades, this has led some researchers to study the way people really make decisions, rather than relying on the old theoretical models. They study how people actually make decisions, rather than assuming they always decide in a perfectly rational manner. Their work has helped to uncover the highly complex and chaotic system that is reality. It has also enabled us to recognise and understand the cognitive biases we are all subject to in making decisions. Out of this has come an understanding of how we can improve our decision-making skills by managing these cognitive biases.

This new field of study is called behavioural finance. It has probed into how we behave in a wide range of situations, including how we determine a price for something and how investors behave in stock markets. In the stock market, they carry out this research by observing and measuring exactly what people do and assessing the results they achieve.

One study by Brad M. Barber and Terrance Odean examined the trading results for 78 000 accounts at a large US discount broking firm from 1991 to 1996. A discount broker was chosen because it was far more likely that their clients were making their own decisions than at a full-service broker, where they would be acting on advice from a broker/salesperson.

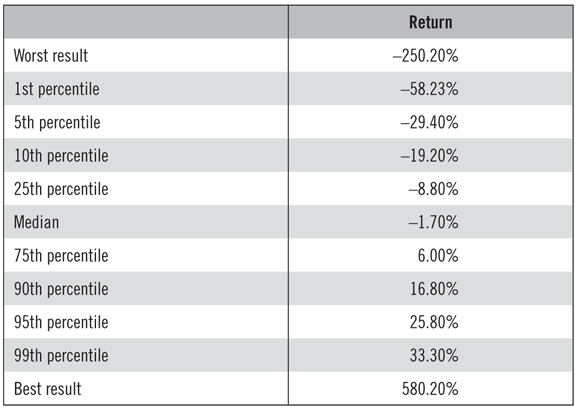

The performance of the 78 000 traders was measured against the benchmark return that would have been obtained if they had done no trading over the year, but just held the stocks they had at the start of the year for the 12 months. The results indicate that they would have been better off not trading at all, because their start-of-the-year portfolio would have performed on average 2 per cent better than they actually achieved from trading. Table 2.1 summarises the results.

Table 2.1: Summary of the results arranged by percentile

Source: The Common Stock Investment Performance of Individual Investors, 1998 working paper by Brad M. Barber and Terrance Odean.

The clear conclusion is that only the best 10 per cent of traders went anywhere near matching the broad market index for the period. This is roughly in line with many previous studies, which indicate that at least 90 per cent of traders fail.

Now, when most beginning traders see this table, it does not bother them very much. Indeed, if your response to this table is the same as theirs — that they do not have a problem because they are one of the top 10 per cent — then that is exactly the idea that behavioural finance researchers call overconfidence.

Researchers have studied people from many professional fields. The results consistently show that, when making subjective judgements of situations, we all tend to overestimate the precision of our knowledge about most things. When people think their judgement is better than it measurably is, researchers say that they are overconfident.

Not surprisingly, researchers have demonstrated that overconfidence is greatest when the judgement involves difficult tasks, forecasting things that are difficult to predict and the lack of fast, clear feedback.

If we think about trading for a moment, we must conclude that trading is just such a situation. Indeed, leaving the full trading process to one side, just the initial step of selecting a stock is clearly a difficult task, where prediction is problematic and feedback is confusing and uncertain.

It therefore follows that stock selection is the very type of task for which we are likely to be overconfident.

Among traders the characteristic of overconfidence sets up a process, starting with the way we overestimate our knowledge about the value of a stock. We think that our information is deeper and more precise than it really is. Moreover, we seriously overestimate the probability that our assessment is more accurate than that of other traders. This intensifies differences of opinion among traders, which leads to more trading.

To examine this idea, the researchers divided the 78 000 traders at the discount broking house into five groups arranged from lowest turnover to highest:

• The least active 20 per cent turned their money over an average of 2.3 times a year. On average they made a net gain of 18.5 per cent a year.

• The most active 20 per cent turned their money over between 104 and 250 times a year. On average they made a net gain of only 11.4 per cent a year.

Clearly, the more they traded, the more they hurt their wealth creation efforts.

To try to demonstrate more conclusively that overconfidence leads to more frequent trading and poorer results, the researchers looked for ways to compare those they knew to be overconfident with those they knew to be less overconfident. There was a great deal of previous research to help them in this.

Previous research had shown that both men and women are overconfident. However, it also showed that men are generally and measurably more overconfident than women. An important aspect of this is that it depends a great deal on the task for which the overconfidence is being measured. For example, men generally claim more ability than women, but this is much stronger for what are seen as masculine tasks.

Previous research also showed quite clearly that men are inclined to feel more competent than women do in financial matters. Therefore, if men were generally more overconfident about finance than women, studying the trading results of men compared with women would be a good way to test the effect of overconfidence.

In looking at the broking house clients’ results, the researchers obviously had to exclude accounts that were clearly those of married couples, because they might have influenced each other’s decisions. Therefore, they focused on accounts in the name of single men and women. The first thing they looked at was turnover, or trading activity. The turnover for the women was 50 per cent, but for the men it was 85 per cent.

Then they looked at the all-important net results. Again, they measured them against the result if their portfolio at the start of the year had remained fixed. Both men and women under-performed against the static portfolio they had started the year with. Their trading had resulted in women under performing by 1.45 per cent a year. Unfortunately for the men, their underperformance was worse, at 2.9 per cent a year.

Here are some other gender differences that this and other research shows:

• When feedback is immediate and clear-cut, women and men are equally overconfident. When feedback is absent or ambiguous, women are less confident than men. Stock market feedback is mostly ambiguous, so men are destined to be more overconfident.

• Investors take too much credit for their successes. This bias is greater for men than women, so men become more overconfident.

• Men spend more time than women on money and financial analysis. They rely less on brokers. They make more transactions. They have a greater belief than women do that returns are predictable. They anticipate higher returns than women do. All this makes men behave more overconfidently.

• Both men and women traders bias their portfolios to smaller and more volatile stocks, but women do so less. Thus, after accounting for risk, women earn reliably higher net returns than men.

There it is — women are better traders than men, because they are less overconfident. However, before women take this as carte blanche to take over the trading, remember that both men and women are overconfident and that both detract from their wealth from trading; men simply do it more often and more destructively. The research strongly suggests that both would be better off financially if they traded less often.

The next chapter will explore overconfidence in more detail and a wider context. At the end of it I will provide some strategies for dealing with overconfidence generally.

Summary

Behavioural finance explores the real world rather than developing theories based on unrealistic assumptions. One study showed that 90 per cent of traders produce lower results than buy-and-hold. The problem is overconfidence — an overestimation of our trading ability. Another finding was that the more transactions a trader made, the lower their results. Both men and women are overconfident, but men are more overconfident than women.