CHAPTER THREE

The Village . . . The Cyclone

THE DESTRUCTION OF a frontier town by the forces of hostile nature first appeared in the Wild West show’s 1886 season, in Madison Square Garden. The expectant crowd sat before a mining camp with a row of army tents. “Thunder is crashing and light[n]ing flashing,” wrote a reviewer. “Suddenly comes a roar, the tents sway and then are leveled, several dummies are whirled wildly in midair, and the curtain drops on what is supposed to be the terrific destruction of a camp by a cyclone.”1

The scene evoked the contest between savage nature and “the advance of civilization,” which was the Wild West show’s main plot. 2 The mock natural disaster—a kind of “Attack on the Settler’s Cabin” writ large—was heavy on mechanical special effects. To simulate a tornado, managers dug a trench to a steam generator across Twenty-seventh Street. The generator turned four six-foot-tall industrial fans inside the showplace, which produced a heavy wind—“the first time on record,” wrote the stage manager, that “real wind was used as an effect.” 3 Stagehands gathered a mountain of leaves and brush from city parks and roadsides, and poured wagonloads of debris in front of the fans, which blew it across the stage, visually accenting the gusts.4 Of course, in the outdoor arenas where the show usually appeared, these preparations were impossible. So the scene of town destruction was reserved for the comparatively rare indoor venues with suitable infrastructure, the industrial machinery behind the spectacle suggesting the advanced stage of civilization which the town represented. In 1887, in Manchester, England, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West moved indoors for the winter, and the town destruction—before a gale measured at over fifty miles per hour— became the show finale, with “legitimate wind effects by the Blackman Air Propeller.” 5 In 1907, again at Madison Square Garden, the mountain village collapsed again, this time under an avalanche whose staging remains a mystery. 6

AT LEAST SINCE John Winthrop invoked the “city on a hill,” town building had expressed America’s frontier progress. In keeping with this tradition, the Wild West show’s towns were the figurative culmination of westward-marching civilization. Cody grew up with such notions, which were widespread on the Plains by the time the Civil War came to a close. When a train pulled into Sheridan, Kansas, in November 1869, a correspondent on board described the new town as “an apparition of civilization amid the solitudes of the Great American Desert.”7

In fact, despite popular ideas of towns as the endgame of western development, urbanization went hand in hand with frontier expansion. In the transient world of the Far West, to found a town made one a creator of the fixed institutions of governance, domesticity, and capital. The trade and rising real estate prices of towns made them a short path to wealth and respectability for lucky founders. Even in eighteenth-century Kentucky, Daniel Boone, that paragon of frontiersmen and hunters, had joined partners in creating the town of Boonesborough. He never made any money from it, but by the 1850s the founders of such frontier towns as Des Moines, Davenport, and Moline, to say nothing of Chicago, were respected, and sometimes wealthy.8

William Cody’s exposure to frontier horsemanship, hunting, and Indian fighting fit our modern notions of frontier life, but it comes as something of a surprise to learn this backcountry man came of age amid fervent urbanization. In Kansas, hysteria for town-founding rose and fell with each pulse in the river of emigrants. As the Cody family joined other settlers there in 1854, speculators were founding no fewer than fourteen towns along the steamboat route of the Missouri River, and others farther inland. So eagerly did speculators like Isaac Cody lay out plans for settlements like Grasshopper Falls that humorists warned some land should be reserved for farming “before the whole Territory should be divided into city lots.” Kansas emigrants had such faith in town futures that beautifully colored printed deeds to properties in towns-yet-to-exist served as money. According to one observer, shares in cities consisting of a shack or two “sold readily for a hundred dollars.” The flutter of land certificates and the clink of gold coin attracted poor men in droves. “Young men who never before owned fifty dollars at once, a few weeks after reaching Kansas possessed full pockets, with town shares by the score.” Isaac Cody’s speculation in some town was practically a foregone conclusion. After all, even “servant girls speculated in town lots.”9

The town of Grasshopper Falls was a success. But William Cody’s father seems to have known that most town-promotion schemes in the West failed. Competition for emigrant traffic was fierce. Of the fourteen would-be metropolises established along the Missouri River in Kansas, only three survived. Isaac Cody did not let his success run away with him. He even refused an invitation to invest in the new town of Leavenworth.10

Not surprisingly, after the Civil War, as hundreds of thousands of new emigrants poured into the state, town creation was much on the minds of Kansas settlers. But now it was complicated by the technology of the railroad. Boosters had been calling for a transcontinental railroad since the 1830s. In 1861, after the South’s departure from Congress finally broke the political logjam over the transcontinental route, the Union Pacific Railroad received the contract to lay the tracks from Omaha to the West. Other railroad financiers, led by the western surveyor-hero John C. Frémont, broke ground on a railroad to connect Saint Joseph, Missouri, to Denver by building a direct route through central Kansas. They began at Leavenworth in 1863 and, anticipating a buyout by the larger line to the north, they called their road the Union Pacific Eastern Division, or the UPED (later it would be called the Kansas Pacific).11

Of course, settlers followed the rails. Once the well-watered eastern edge of the state was behind them, they entered a more arid, threatening land. Rainfall was relatively sparse. The rolling hills and streams gave way to flatter, short-grass plains, with fewer sources of water, vast herds of buffalo, and large numbers of Indians who were often less than pleased at this invasion of their homelands. In defiance of Indians and the weird Plains environment, towns sprouted along the rails at Ellsworth, Hays, Junction City, and other places.

In the immediate aftermath of the war, William Cody followed those same rail lines on a path that led him both to create a family for himself—his own settler’s cabin—and to attempt ensconcing them in a new community of his own design, a town by the railroad. His little family was a shaky proposition, and his domestic life was not helped by the sudden collapse of his village. In a strange foreshadowing of the staged destruction of the Wild West show, the failure of his town looked like a natural disaster. But it was industrial might, not hostile nature, that destroyed it.

Twenty years later, the Wild West show functioned as a kind of traveling community, and its success was a product of the many railroads which allowed its props, its dozens of animals, and its hundreds of people to move from town to town. Just as railroads brought Cody’s show to city lots, they carried audiences from the surrounding countryside, usually at special rates negotiated by Cody and his agents. Later, just before the twentieth century began, Cody would turn again to the creation of a more conventional town, this time in arid Wyoming. There, one of the first steps he took was to secure railroad support for his settlement. William Cody learned the need for alliances with railroads, and he did it during the late 1860s, as a consequence of his first attempt to create a frontier community. Here, the entrepreneurial William Cody learned a hard lesson in the power of corporations and the new railroads. It stayed with him all his life.

ANY ASPIRATIONS to becoming a mythic hero were not in evidence upon Cody’s return from the Civil War. Back in Leavenworth, he returned to his series of odd jobs and ephemeral business ventures. For a few months he drove a stage for a transport company in western Nebraska, between Kearney and Plum Creek. It was “a cold, dreary road,” and in February 1866, bouncing over its muddy ruts in the frigid air, he decided to “abandon staging forever, and marry and settle down.” He returned to St. Louis, where he and Louisa Frederici were married on March 6, 1866. Immediately after the wedding at her parents’ home, they took the steamboat north and returned to Leavenworth.12

Louisa Maude Frederici grew up in the French-speaking quarter of St. Louis. Her father was an Austro-Italian, French-speaking immigrant from Alsace. Her mother may have been an American woman. Louisa Cody claimed she was, and that her maiden name was Smith. But William Cody described her as a German who spoke the language fluently. We know little about Louisa’s early association with William Cody, except that they met during the Civil War, and that they had a jocular courtship. Superficially, they seemed well suited to one another. To Cody, she was a dazzling, beautiful woman at home in the largest city he had ever seen. We can only guess at his attractions for her. He was very handsome. He exaggerated his prospects throughout his life, and there is no reason to believe he did otherwise then.13

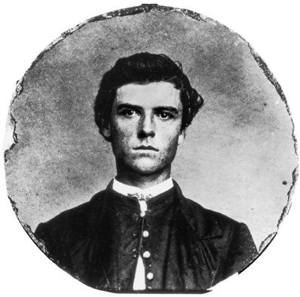

William Cody at eighteen. Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

Louisa Frederici Cody, at about the time of her marriage to William Cody. Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

In any case, Louisa was the child of merchants, and she expected a middle-class life when she married William Cody. Almost immediately, she began to have doubts about her choice of a husband and his financial capabilities, both of which would trouble her for the rest of her life, even after he began to make large profits in show business.14 Moving back to Leavenworth, Cody took along with him a desire to make a new family around him, and to restore to them the life of relative wealth the Codys had lost since the death of Isaac. In this, Louisa was supportive, but she demanded certain guarantees. She wanted no roving plainsman for a husband. He must settle into a paying business.15

Hoping to profit from the widening flow of migrants through the region, William Cody rented his mother’s old house from its new owners and opened it as a hotel called the Golden Rule House. Four miles west of Leavenworth and near several arteries of western emigration, it was an ideal location for a business that provided emigrant services.16 Like most of Cody’s ventures, this one was a failure, owing in part to his tendency to spend money faster than he made it, a characteristic which was better suited to the nomadic, raiding economy of the jayhawker than to the fixed business he was trying to run.17

The strains of the new business pervaded a house already filled with tension between his wife and his sisters. Initially, he and Louisa stayed with his sister Eliza, who was now married to George Myers. When they moved out of the Myerses’ house, little sister Helen Cody moved in with them. Although Helen and Louisa got along at first, they eventually quarreled, and the relationship was never close thereafter.

“She was always wanting a home of her own,” recalled William Cody of his wife, many years later, “and of course I was young . . . and I didn’t know anything about business and I couldn’t get a home in a minute.”18 Money problems aggravated their personal differences, especially as Louisa was soon expecting a child. In September, William Cody gave up his lease and abandoned the Golden Rule House. Leaving his pregnant wife in a rented house with his sister Helen, he “started alone for Saline, Kansas, which was then at the end of the track of the Kansas Pacific railway.”19 He was breaking his promise to settle down, and their parting words must have been acrimonious. He would not return to Louisa for the better part of a year. Their first child, a daughter, Arta, was born in December, while he was away.20

Thus began the self-exile from his own hearth that characterized most of Cody’s adult life. What began right after the Civil War as a marital estrangement became standard when he was touring with his theater company and, after that, the Wild West show. Ironically, the man who became a hero for saving the frontier family home did so primarily by seeking to escape his own troubled house. For Cody, roving as plainsman or showman was usually preferable to the stationary combat of his fireside.

OUT IN WEST KANSAS, at “the end of the tracks,” he scrabbled for a livelihood among mostly low-class frontiersmen: down-and-out prospectors, cowhands, buffalo hunters, and teamsters who moved from job to job, with no fixed address. The cash economy of Kansas had been expanding for most of William Cody’s life. After the Civil War, a wave of new Kansas emigrants, combined with a dramatic increase in railroad and other investment, fueled spectacular economic growth. The railroad, especially, brought about a tectonic shift in the prairie’s social, economic, and natural relations. Nowhere was that fact more apparent than where the rails extended farthest into the frontier. At track’s end, thousands of Irish tracklayers, or “gandy dancers,” pounded spikes into ties and did the other work of building the railway toward the western horizon. From the other direction came hundreds of bullwhackers from Mexico, the United States, and points unknown, whips cracking beside prairie schooners creaking with tons of Colorado and New Mexico cattle hide, sheep’s wool, buffalo robes, and mineral ore, all to be sold at the railroad’s western terminus. At the same time, the east-west migration of goods and people swelled with a northerly flow of mostly poor and young cowboys—white, black, Mexican, and mixed-blood Texans—driving huge herds of cattle to these newly minted “cow towns,” from which 50,000 animals were shipped east in 1868 alone.21 On top of all this, black, white, and immigrant soldiers, merchants, laborers, speculators, entertainers, and tourists, the wealthy and those of middling means, came west on the railroad. Settlers followed not long after.

The rivers of mostly male workers—flowing ahead of the train, alongside the prairie schooners, and behind the cattle—converged in one vast lake of loneliness and thirst in the arid plain. Entrepreneurs took advantage. To the north, in Nebraska, the Union Pacific Railroad created a genuine moving town, famously called “Hell on Wheels,” where drink, food, and sex could be had for cash, and where card games, shell games, real estate swindles, and a hundred other ways to cheat men of their money proliferated. End-of-the-line social relations were similar even in more permanent towns on the UPED, where boomers waxed rhapsodic about civilization, but other observers were more critical. “The houses” in Ellsworth, remarked one traveler, “are alternately Beer Houses, Whiskey Shops, Gambling houses, Dance houses and Restaurants,” wherein patrons consumed large quantities of beer, whiskey, and “tarantula juice.” 22

As Cody later recalled it, when he was testifying in his own divorce trial, the first year away from Louisa he was “railroading and trading and hunting; I went out to make money and I was just looking around for anything that would come along.”23 He spent the winter like many other single men on the Plains: in a “dugout,” a hole in an embankment with a crude roof over the top, sharing the dark, dingy space with a man named Alfred Northrup. Early in 1867, he helped a former neighbor from Leavenworth haul goods to open a new store. He mixed his odd jobs with stuttering efforts at founding a business. That summer, a series of drunken, bloody melees between soldiers and railroad workers compelled army officers at Fort Hays to seize the supplies of unlicensed booze merchants. In their dragnet, they confiscated the stores of William Cody, which included, among other things, four gallons of whiskey and three gallons of bitters. 24 The well-known mule-whacker and aspiring saloonkeeper was also a peddler of buffalo meat on the streets of Hays; locals soon took to calling him Buffalo Bill.25

The name itself long preceded him. On the Plains, when any number of men were named Bill, appending “Buffalo” as an epithet was a way of distinguishing among them. In the 1860s and ’70s there were Buffalo Bills in Texas, Kansas, and Dakota Territory. As early as 1862, an English traveler in Montana would record his meeting with “Buffalo Bill, a personage whom I have hitherto regarded as a myth.”26 The name may have been applied to Cody in derision, as a taunt. But however he earned the moniker, in the long run it was a boon to his notoriety. The name was so endemic to the frontier that upon being introduced to the Buffalo Bill, many believed they were meeting a man of wide reputation, even if the Buffalo Bills they had heard about were different men.

In his long absences from home in the 1860s, this Buffalo Bill’s career resembled a low-rent version of his father’s. Before Isaac Cody’s troubles with pro-slavery settlers began, he had been kept away from his family by the demands of his own stage line, and by the burdens of managing large farms for absentee investors and of founding successful towns. William Cody’s stints as teamster, whiskey seller, and market hunter were of a lower-class variety.

So, too, was his next venture, when he joined a man named William Rose in a contract to grade track for the UPED.27 It was hard, dusty work, driving teams of horses behind the scraper blades which pulled up the prairie sod and churned grit into the air. Although he continued to send Louisa money, there was no way she would join him in this peripatetic life, with no fixed home and surrounded by men of low standing and hard disposition.

Then he made an audacious move. In the summer of 1867, he joined with Rose in founding a town along the course of the railroad near Fort Hays. The young men’s faith in the advancement of civilization and their own interests, their conviction of the town’s permanence and eventual greatness, was expressed in the name Cody chose for it: Rome.28

Cody and Rose would soon learn that, where the game of town-founding had been risky in the 1850s, it was even more treacherous for entrepreneurs in the 1860s. Along the wagon roads, travelers could stop at any roadside settlement or outpost that looked promising. Town founders secured their business and recruited new residents by appealing to emigrant needs.

But train passengers could alight only where railroad executives decided to schedule stops, and in this matter they played a rough game. Corporate survival hinged on settling a dependent population of customers along the tracks. Without farmers, merchants, and others to buy space for their freight and seats for themselves, long stretches of track would be too expensive to sustain. Company executives thus took special interest in town sites, exercising near-monopoly control over their selection. The most charming settlement along the path of the railroad, however thriving and complete with businesses, families, churches, and schools, would turn to a ghost town if the railway company failed to schedule a stop there. Indeed, as the railroads extended along the route of older emigrant roadways, preexisting hotels, stores, saloons, and other provisioning stations were forced to find a niche in the railroad’s towns or face bankruptcy. In a curious way, the “civilizing” force of the railroad brought greater commerce at concentrated points along the tracks, but it cleared many Plains entrepreneurs from their holdings, leaving open prairie along the old trails where scattered homes and businesses had once stood.29

Thus, in the interval between the death of Isaac Cody and the arrival of the railroad in western Kansas, the opportunity to build towns moved out of the hands of entrepreneurs and into the hands of huge corporations. In the East, railroads were built to connect towns. In the West, railroads were built first, and the towns followed. Railroad agents, sent west to locate depots along the intended route of the railway, frequently threatened to pass existing towns by if they did not receive donations of free lots to line their own pockets. Independent town founders who succeeded in getting the railroads to build depots were usually men of considerable means, some of whom bought up every conceivable nearby railroad stop and forced the railroad to build the depot in the town.30

To circumvent such tactics, railroad companies such as the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific, fueled by vast sums of investor capital and taxpayer subsidies, organized subsidiary town-building companies. On occasion, when they were bribed enough, they ran the rail line through or beside an existing town. But more often they steered away from settlements so as better to exploit the economic boom the railroad brought with it. At Cheyenne, Wyoming, for example, the Union Pacific established the town, organized the local government, and sold lots only to people who acknowledged the railroad as rightful owner of the property—all before the company even had title to the land.31

Railroad power over town creation was perhaps most potently symbolized by the shipping of the physical stuff of new settlements to the frontier. The Union Pacific and other railroads freighted whole towns in pieces, like giant toys. One western traveler reported a train loaded with “frame houses, boards, furniture, palings, old tents, and all the rubbish which makes up one of these mushroom ‘cities.’ ” As it pulled into Cheyenne, “the guard jumped off his van, and seeing some friends on the platform, called out with a flourish, ‘Gentlemen, here’s Julesburg.’ ” 32

Still, even with the might of America’s railroad magnates against them, independent speculators frequently tried to horn in on the railroad’s town business. Many simply bought and sold lots in towns founded by the railroad. “Thousands of dollars are daily won and lost all along the line by speculating in town lots,” wrote one observer. But the boldest speculators would claim acreage for a homestead directly in the path of the railroad. Instead of plowing fields and making farm improvements, as the Homestead Act intended, they laid out a grid of streets, and made public promises that the railroad would build a station there. These “town founders” would then sell lots to other speculators. Deeds for town properties sold and resold at increasingly exorbitant prices as the end of the tracks approached. Their pockets stuffed with coin, the claimants could exercise their option—written into the Homestead Act—to pay the government $1.25 per acre rather than wait five years for their title. The price of lots rose as the railroad came within a day’s ride. It rose again as the dust of the scrapers on the rail bed hung like a dull cloud on the horizon. It crashed when, as almost always happened, the rails passed the town by.33

Ignoring the risks, Cody and Rose took this ambitious route. Using Rose’s teams to grade the site of the new town, they laid out a grid of streets. They offered free lots to anyone who would build on them, although they reserved the corner lots and some other choice locations for themselves. Before long, the town consisted of thirty houses, some stores and saloons, “and one good hotel.” The young men thought they were rich. 34 Cody himself opened a store in a wood frame building with a tent roof. To Louisa, he wrote that he had a home, and that he was worth $250,000. In less than two years on the Plains, Cody seemed to have recaptured his middle-class standing, and to have met Louisa’s demand that he become a businessman. Soon after, he met his wife and baby girl at the end of the track, and the little family became Romans.35

Louisa appears not to have realized that his wealth was paper. Since the town’s businesses had yet to attract settlers willing to pay money for land or services, Cody continued his other, less esteemed employments. Most of his income came from hunting buffalo for Goddard Brothers, contractors who supplied meat to the gangs of Irish railroad workers along the UPED. For bringing in twelve buffalo per day, he received $500 a month, a sizable sum. In addition, he had his whiskey-selling enterprise (at least until the officers seized his supply).36 It was a bold—some might say foolish—leap for a buffalo hunter and whiskey runner to make a grab at founding a town. Nonetheless, Cody wove these divergent business ventures into one another, using the profits from one to underwrite the others.

William Cody’s Rome was built in a few days. It collapsed even faster. The railroad sent William Webb, their division agent, ahead of the rails to select the next town site. Many years later, Cody recalled that when Webb arrived in Rome, “I thought I was going to sell him quite a number of lots from the way he was looking the town over.” When Cody announced he was off to hunt buffalo, Webb “expressed a desire that he would like to kill a buffalo himself.” Cody took him along, and Webb indeed shot a buffalo. The railroad agent “was so delighted and seemed so happy over the killing [of] a buffalo that I thought I would sell him a block when I got back that night.”37

But Webb was not interested in buying any lots. Instead, he proposed to make a railroad stop in the town, for a heavy price. The next morning, as Cody prepared to go hunting again, Webb “came up to me and he offered me one-twelfth interest in my own town. I thought he had gone daft and I rode off and left him.”

Cody was gone for three or four days. On his return, “when I came within sight of where the town of Rome had been when I left there, I discovered that most of the houses had pulled away or gone some place or a cyclone had struck the town, and something was the matter.” He could “see people pulling down the houses and I could see a string of teams moving lumber and everything away from the town.” Webb had designated a new town, to be called Hays City, several miles to the east. The railroad stop would be there. With lumber and building supplies scarce and expensive, settlers were removing all they could carry and carting it to the new settlement.

Louisa looked “rather blue,” Cody recalled. “Where’s the $250,000 that you are worth?” she asked. “Well, I told her that I expected it had gone off with the town, that I was busted.” Years after, Cody likened Webb to a barbarian: “That little fellow made Rome howl.”

William Cody and his family soon followed Rome’s other settlers, pulling down their buildings, carting the expensive lumber over to Hays, and rebuilding. For a few weeks he and Louisa again tried to run a hotel in Hays. But his diminished prospects only made their quarrels worse. By fall of 1867, she had taken the baby and gone. This time, she did not go to Leavenworth. She moved back to St. Louis, and into her parents’ house. 38

Rome joined the burgeoning ranks of Kansas ghost towns, which included a Monticello, a Paris, and a Berlin, whose names reflected the grandiose visions of their would-be founders.39 As Cody watched his little family recede into the distance, he had lost not only his town, but the flesh and blood of his settler’s cabin.

BUFFALO BILL’S WILD WEST show would position Cody as the quintessential frontiersman who had “passed through every stage of frontier life.” The notion that the frontier developed in “stages” was never more explicit than in the show’s first indoor appearance, in 1886. During the summer, Cody and his managing partner, Nate Salsbury, hired Steele Mackaye, a renowned New York dramatist, as stage director for the Madison Square Garden appearances, and charged him with designing an indoor presentation. Mackaye billed it as “A History of American Civilization.” He organized it into a series of epochs, each more advanced than the last. The “First Epoch” was “The Primeval Forest.” It was followed by “Second Epoch. The Prairie,” “Third Epoch. The Cattle Ranch,” and finally, “Fourth Epoch. The Mining Camp,” during which Cody’s stage town blew away.40

According to Steele Mackaye’s son, Percy, the Wild West show was a formless extravaganza before the great playwright got his hands on it, “the performances, though delightfully fresh and vibrant, were still very sketchy and disjointed, wholly lacking in dramatic form.” To address this deficiency, Steele Mackaye invented the separate “epochs” and their sequence. The passage of the frontier to ever higher stages of civilization presaged the most famous theory of western development, put forward in the historian Frederick Jackson Turner’s 1893 essay, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” In a paper delivered to a gathering of historians at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (while Buffalo Bill’s Wild West appeared nearby), Turner argued that Americans passed through stages of social evolution on the frontier, from hunter, to herder, to farmer, and then to urban industry and commerce.41 Although the details of Mackaye’s “epochs” differed somewhat from Turner’s stages, they were in remarkable concordance. Percy Mackaye was convinced that such sophisticated ideas could not have occurred to William Cody, rustic frontiersman that he was. Writing in 1927, he declared, “The outstanding dramatic ideas embodied” in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West “were Steele Mackaye’s ideas.”42

The notion that any grand theories of progress embedded in the Wild West show originated with well-read publicists, not the Wild West showman, echoes through many Cody biographies. But, in fact, settlers usually perceived events on the Great Plains as expressions of stages in the advancement of civilization, to which their own lives were more or less tied. In this respect, Cody’s hunting and town-building each had a symbolic importance, and were not separate occupations so much as the beginning and ending of a single story. In 1886, Mackaye’s ideas on the subject of stages of development (to say nothing of Turner’s in 1893) were only recent derivatives of very old and widely popular political thought. For at least a century, philosophers and popular writers in Europe and America had theorized that all societies advanced through stages of subsistence, and usually these included at least four: hunting, pastoralism, agriculture, and commerce, the last being characterized by peaceful towns and cities. Each stage was a necessary step, and it prepared the ground for the stage that followed. Frontiersmen who stalked wild game represented the first chapter in a progressive narrative of history yet to unfold. Clearing the land of wild animals was a precursor to abundant farm fields and the rise of towns. Hunting was the beginning of the story of civilization.43

Such theories had special resonance in the West because they corresponded—or seemed to correspond—to the visible world. In the minds of a great many travelers and commentators, the trail from frontier to metropole led through all phases of civilization. Thomas Jefferson opined that a traveler journeying from the Rocky Mountains to the East Coast would discover, in successive stages, Indian hunters with “no law but that of nature,” then Indians who were “in the pastoral state, raising domestic animals, to supply the defects of hunting.” Continuing eastward, the traveler would come upon “semi-barbarous citizens” of the United States, followed by “gradual shades of improving man until he would reach his most . . . improved state, in our seaport towns.” Such a journey, Jefferson concluded, “is equivalent to a survey, in time, of the progress of man from the infancy of creation to the present day.”44 Numerous other writers agreed. To travel from frontier to town was to journey through time, along the road of progress.

To live between frontier and town, and to bring about the creation of settlements on the Plains, was to partake of progress, to make history. The Codys did not spend long evenings poring over Jefferson or other four-stages theorists. But they were highly attuned to the need for land clearing as a prelude to settlement. The prosperity of the settled East, and indeed of Louisa’s own Missouri, had been wrought from wilderness only through the eradication of wildlife and the felling of forests. Partly for this reason, Plains settlers routinely shot every living animal that was not privately owned, training their guns not only on marketable buffalo, elk, and deer, or on vermin wolves and hawks, but also on inedible and unsalable jackrabbits, badgers, porcupines, sparrows, and chickadees.45 By the 1860s, in popular accounts of every locality, Americans narrated their history as progress through wildlife destruction, the westward march of civilization marked by elimination of game.46

In this connection, market hunting was a central feature of the popular ideology of progress. By converting bison to cash, buffalo hunters simultaneously made a civilized commodity out of savage nature, took bison from Indians, and cleared the grassland for domesticated livestock and the next stage of civilization. The ascendance of pastoralism was unmistakable in the vast herds of Texas cattle lowing their way to Kansas railroad depots. Cattle would eventually give way to crops. Homesteaders were already staking out farms along the railway. Surveyors predicted that Kansas would soon become “the great wheat-producing region of the world.” 47 As a market hunter, Cody’s work assumed mythic proportions as a nearly ritual passage for his society.

From the fall of 1867 through most of 1868, Cody hunted buffalo.48 He was well-known as “Buffalo Bill” by this time, and the Hays City Advance mentioned his hunting exploits occasionally, such as the day in January 1868 when he brought in the carcasses of nineteen animals. Selling the meat at seven cents per pound, he earned $100 per day. 49 He also continued to hunt buffalo for Goddard Bros. until the railroad reached Sheridan.

Killing buffalo and marketing them were some of the most familiar practices in the entire country. Indians had been hunting buffalo, and trading robes, meat, jerky, and other goods to one another, for nine thousand years. Among Americans, there had been a sizable market for buffalo tongues and robes since the 1840s, when Indian hunters brought these commodities to trading posts, from which they were shipped down the Mississippi River to St. Louis and New Orleans. In 1850 alone, some 100,000 buffalo robes passed through St. Louis.50

Before the Civil War, rot and insect infestation kept many robes from reaching more distant consumers. But the extension of the railroad onto the prairies of Nebraska, Kansas, and Texas made it possible to bring smoked buffalo tongues and robes to eastern markets with less fear of spoilage, ushering in a revolution which would destroy the last of the great herds, and most of the Indian social customs and traditions which had grown up around them. In the cities and towns of the United States, consumers bundled themselves into buffalo coats and covered their laps with woolly buffalo robes as they set out by sleigh or wagon in frosty winters. The prices for meat and robes in the cities were augmented by the new markets at the army forts and in towns like Hays (and the more ephemeral ones, like Rome) that were rising rapidly across the Plains. Later, in the early 1870s, tanneries would perfect a method for turning buffalo skins into quality leather, touching off the last great surge of bison hunting. But until then, bison hides were only useful when they came from winter coats.51 For this reason, Cody’s market hunting was particularly intensive during the cold months.

In the Wild West show, Cody reenacted a buffalo hunt that featured himself with several cowboys and Indians, all on horseback, firing blank cartridges at a small herd of buffalo wheeling around the arena. There are no eyewitness accounts of Cody’s market hunting, but our knowledge of the industry suggests his hunting trips differed considerably from this scene. For one thing, hunting required a support staff of nonhunters, including skinners and butchers. When he was a meat hunter for the UPED, Cody took along a butcher, who drove a wagon to carry the meat. He likely shared the proceeds with a small camp staff throughout his market hunting forays in the late 1860s.52

But more significantly, market hunters rarely, if ever, hunted on horseback. It was hard to aim from a moving horse, and other factors made it pointless to try. Buffalo have a superb sense of smell. They have difficulty seeing people on foot, but no trouble seeing horses. Their sense of hearing is acute. A man on horseback was too prominent to get near a herd without the animals thundering into the distance. For this reason, Indian hunters on horseback attacked herds from all sides simultaneously.

Bison herd defenses had several holes, though, which market hunters exploited. The sharp sound of a rifle did not signify a threat unless it was accompanied by the cry of another bison in pain or distress. So most market hunters hid from their quarry by approaching from downwind, then sitting or lying prone. Aiming a large-caliber rifle, sometimes mounted on a tripod for accuracy, they gunned first for the lead cow, the dominant animal in the herd. If their marksmanship was good, the bullet shredded the animal’s heart, and she dropped to the ground without making a sound. The herd stayed put or, if another cow moved out to lead the herd, the hunter then killed her. In a short time, the animals would be confused. They stood still, or milled around. The hunter could fire away until the herd moved out of range, which might not be until most of them were dead.53

Felling buffalo after buffalo in this way was called a “stand.” Most American market hunters were young men, and most of them probably ventured onto the buffalo grounds for brief stints in the fall, during the seasonal lull in farm or ranch work. Their marksmanship was usually inadequate to effect a stand, and the herds were wary enough that the hunters had great difficulty getting close enough to make a kill. After two or three weeks, they might return with only a dozen hides, or less.54

Still, in the many Great Plains stands of the late 1860s, sizable parts of herds vanished in the space of hours. Legendary market hunters were known to kill upward of eighty animals in a single day, sitting in one spot. But skinners could process only so many animals before the carcasses spoiled, so most killed no more than thirty. In any case, when the shooting was done, the butchers took over. Cody’s butcher removed the back legs and hump. Some took the tongue. Since Cody did a good deal of hunting in the winter of 1867–68, we may presume that he and his butcher also took skins to sell for robes. Once the wagon was full or the quota was met, they returned to camp, leaving the carrion to rot or be eaten by scavengers.55

Like that of his fellow market hunters, Cody’s buffalo hunting was oriented more toward volume than style, and he likely hunted the animals on foot. His favorite gun for buffalo hunting was a reconditioned .50-caliber rifle that could kill a buffalo at six hundred yards, a Springfield “needle gun” (so named because its new technology of the firing pin reminded early shooters of a needle). Market hunters preferred the gun for its accuracy and its heavy ball, which could render a wounded bison incapable of charging, something hunters on foot had reason to be concerned about.56 Cody himself calculated that he killed 4,280 buffalo in his eighteen months as a market hunter. Figuring that he had a total of 360 working days in this period, he would have needed to kill fewer than twelve buffalo a day to reach that number. If anything, his total is likely low. Later hide hunters, in the early 1870s, would kill as many in a couple of months.57

Modern Americans rarely honor these buffalo hunters, who are commonly remembered as greedy, lowbrow, filthy, and stupid (nowhere more so than in Larry McMurtry’s novel Anything for Billy, where gangs of drooling hide hunters populate the town of Greasy Corners, New Mexico).58 But in 1867, market hunters were somewhat respected. They cleared the land for farmers, and, like fur trappers before them, buffalo hunters were expectant capitalists. They risked their own guns, ammunition, wagons, and other gear—to say nothing of wagering their lives against Indian attack—in anticipation of profit. In many places, they bought their supplies on credit from meat-and-hide dealers in nearby towns, in hopes that their success would allow them to pay off the loan and have something left over. From the ranks of buffalo hunters would come any number of town founders, bankers, and other respectable businessmen. When the Hays City Advance hailed William Cody’s market hunting, it reflected a regional and national approbation of hunters as small businessmen.59

And yet, Louisa lost faith. Even if buffalo hunting retained some respectability as a suitable pursuit for a young man, William Cody’s fall from town founder to simple buffalo hunter left his wife unhappy. She “made little of my efforts to succeed in life,” William Cody remembered long after. She said “that I was a failure and something like that; and we had our little disagreements again. When everything was going all right and I was selling lots of [town] lots,” in Rome, “we seemed to get along pretty well; but when things were different and I wasn’t getting along very well, things were the other way and we could not get along so well.”60

In public, Louisa never admitted to any unhappiness in this early period of their marriage. But something caused her to leave. If the couple’s personal, intimate conflicts are beyond our knowledge, it seems likely that at least some of her discontent stemmed from her husband’s occupation. Frontier hunters played a role in the drama of civilization, but there was a profound difference between men who hunted to create the institutions of civilization—farms, schools, churches, businesses, and towns—and those who hunted to the exclusion of other work. The former were upwardly mobile, their hunting a phase of life which passed with the frontier itself, leaving them established and settled as farmers, merchants, or other businessmen. Traditionally, the latter were low-class, borderline renegades. To Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur, such men “appear to be no better than carnivorous animals of a superior rank, living on the flesh of wild animals, when they can catch them.” The temptations of wilderness indolence overwhelmed their better natures. “Once hunters,” he warned, “farewell to the plow. The chase renders them ferocious, gloomy, and unsociable.” 61

Similar views appeared in the writings of James Fenimore Cooper and a host of other frontier observers. In this sense, Cody did not simply move into another line of work when he lost his town and turned to buffalo hunting. He slipped backward along the path of civilization. He was no longer a town builder. At best, he was merely a clearer of land for other town builders. All of the respectability that attached to buffalo hunting depended upon its being a temporary pursuit. But Cody seemed uninterested in the more permanent occupations he might have taken up. He seems to have abhorred the thought of farming. He claimed no homestead.

Of course, in reality, Cody was not going back in time. For all the rhetoric of civilization’s beginnings among primitive hunters who blazed a path for herdsmen and farmers, buffalo hunters were modern men who relied on the railroad, as well as a host of industrial products, including guns and knives. Cody did not subsist on the meat he shot. He lived on his pay from Goddard Brothers, which, at $500 per month, was the largest salary he earned in the 1860s. This would not have been possible without the presence of a corporate sponsor, in this case the UPED. The subsequent careers of Cody’s cohorts in the killing fields of the Great Plains may have been less colorful than his, but they were just as modern. Carl Hendricks left Sweden for Kansas in 1870. There he hunted buffalo for a year, then moved on to take up work in a New England steel-wire mill.62 Bat Masterson was a market hunter in Kansas, gunning for buffalo only a few years after Cody. He became most famous for his career as a gunfighter and lawman, but eventually moved into industrialized publishing. He was a New York sportswriter when he died.63 Wyatt Earp and Bill Tilghman became legends of frontier law enforcement. Both began as buffalo hunters and ended up in filmmaking, where they sought to mythologize their lives after the example of Buffalo Bill.64

But even in its most modern context, the respectability of buffalo hunting was always tenuous. To see white hunters decimating the great herds reassured most Americans about the forward march of progress. But progress seemed so necessary in part because just beneath the surface lay a more complicated and sometimes frightening possibility. Buffalo hunting required absence from the domesticating influence of home, an institution which was disturbingly ephemeral on the frontier anyway. The passions of lonely men, without the restraining and civilizing influence of women, could find unseemly and dangerous outlets on the open prairie. Through the first half of the nineteenth century, American fur trappers (who assumed the same mythic place as initiators of civilization that other hunters did) frequently married into Indian families. Their reasons were as complex as can be imagined, ranging from romantic love and desire for companionship, to ambition for political alliances with powerful Indian families—to say nothing of the help with the processing of furs which Indian women provided.

Most buffalo hunters saw the occupation as strictly seasonal, and temporary, something to be pursued during the down season on the farm or ranch or when other money was not forthcoming. But the more committed followed the example of earlier trappers. Indeed, some were former beaver trappers who moved into the buffalo robe trade as it supplanted the beaver pelt traffic in the 1850s.65 In Kansas, hunters like Ben Clark and Abner “Sharp” Grover were married to Indian women. Their mixed-race unions placed them outside the bounds of middle-class respectability in the more established settlements, as people with dubious intentions and as race traitors. In fact, throughout the history of the American frontier, such unions predominated only until the arrival of “respectable” white women in sufficient numbers to furnish marriage partners for white men. In other words, the arrival of middle-class white women like Louisa Cody rendered these earlier mixed-race families—and their devotion to market hunting—an anachronism. 66

Settlers were all too aware that most Plains hunters were Indians, and white men who were committed to hunting as an escape from civilization were suspiciously close to them in geography and lifestyle. Indian hunters were the nation’s major source of buffalo robes. Particularly at the trading posts on the upper Missouri, but extending well to the south, Indians traded robes for guns and other goods. Sioux, Cheyenne, Osage, Kaw, Comanche, and other Indians supplied the vast majority of the 200,000 robes brought to American trading posts on the Missouri River in 1870.67

Americans welcomed bison eradication in part because if the animals did not vanish, then neither would the Indians. In the 1830s, Washington Irving and other commentators warned about the temptations of the hunt for white men, speculating that the Great Plains, then known as the Great American Desert, would become a kind of American Mongolia, populated only by nomadic, miscegenated herdsmen and hunters, “a great company and a mighty host, all riding upon horses, and warring upon those nations which were at rest, and dwelt peacably, and had gotten cattle and goods.” 68 The idea of a continuing, lucrative Indian trade disturbed Americans with thoughts of ever more white men and boys drawn into the multiracial hunting grounds, tempted away from farm fields, from the influence of home and civilization, by the chase and by Indian women.

Whether these deep cultural anxieties increased the tensions between William and Louisa Cody is impossible to say. But if her concerns stemmed from the multiracial character or transient qualities of buffalo hunting, she likely felt vindicated when this, her husband’s most symbolically primitive occupation, failed. When the Kansas Pacific reached Sheridan, Kansas, in May 1868, its corporate coffers were empty. Construction ceased. Goddard Brothers lost their provisioning contract, and Buffalo Bill Cody lost his salary.

In June, at a personal “end of the tracks,” he asked Louisa to see him at Leavenworth. She brought baby Arta up from St. Louis. There the couple had a terrible row, so bad that William Cody later recalled, “I didn’t think that we would ever have another meeting; we had kind o’ mutually agreed that we were not suited to each other; she was as glad to go back to her home as I was to go to the plains.”69 Advancing civilization was no easy task. Cody had lost his home, his family, his town.

But there were other opportunities. Upon his return to Hays, Cody turned his eyes from railroad contracts—grading and buffalo hunting—to military contracting. Army provisioning was a principal source of income for ambitious settlers in Kansas. Isaac Cody himself had contracted to sell hay to the army fort at Leavenworth. Across the West, the army hired civilians to serve as guides, teamsters, and blacksmiths, and in various other capacities. 70

Among this latter group of civilian hires were temporary “detectives,” deputy lawmen whom officers appointed to track down and apprehend deserters and stock thieves whom regular army soldiers were unable to catch. Cody had already attempted to make a business in selling liquor to troops, only to have his goods seized by officers. In March 1868, officers at Fort Hays appointed the well-regarded hunter William Cody to the position of detective after several soldiers stole some army mules and deserted from Fort Hays. The officers who appointed him could not have known how inspired a choice they had made, but Cody did. Who better to catch horse thieves than an experienced horse thief?

This small, obscure job assumes an important place in Cody’s story, less for what he accomplished than for the company he kept. On this and on one subsequent detective assignment, Cody rode alongside the deputy U.S. marshal from nearby Junction City. Not much happened on the trail. The two low-ranking lawmen apprehended the deserters and delivered them to authorities later that month.71

But as Cody made his way from frontier Kansas to worldwide stardom, the curious, looming figure of that deputy marshal straddled his path. A tall man with a wide hat and two pearl-handled navy revolvers, standing half in shadow, projecting both promise and menace, he was already something of a myth. His name was James Butler Hickok. But he was better known to his friends, and to his many enemies, as Wild Bill.