CHAPTER SEVEN

Theater Star

EARLY IN 1872, Fred G. Maeder, a prominent New York playwright, adapted Ned Buntline’s Buffalo Bill dime novel for the stage. Buffalo Bill premiered at a working-class haven, the Bowery Theater, in February 1872, starring a noted melodrama actor, J. B. Studley, in the title role. The premiere coincided with Cody’s visit to New York. As Cody told it, “I was curious to see how I would look when represented by some one else, and of course I was present on the opening night, a private box having been reserved for me.” During the play, Studley stepped out of character to announce that Cody was in the theater. “The audience, upon learning that the real ‘Buffalo Bill’ was present, gave several cheers between the acts, and I was called on to come out on the stage and make a speech.” Cody relented, “and the next moment I found myself standing behind the footlights and in front of an audience for the first time in my life.” Not knowing what to say, “I made a desperate effort, and a few words escaped me, but what they were I could not for the life of me tell, nor could any one else in the house.” 1

In a sense, there were two performances that night. In the first, J. B. Studley played Buffalo Bill. In the second, and no less significant, the real Buffalo Bill played the frontier rustic who confronts his own representation in the metropolis. He was following an American tradition, established decades earlier by none other than Davy Crockett. A Tennessean who self-consciously appropriated the symbols of Daniel Boone’s myth on his way to a congressional seat in 1827, Crockett had a tall-tale-telling, homespun persona that was a distinctive touch in official Washington, and he became a national celebrity. His political and social trajectory inspired James Kirk Paulding’s play, The Lion of the West, in which a thinly disguised parody of Crockett named Nimrod Wildfire repeatedly outwits an English snob. Intended as a lampoon of Crockett, the play was received as a celebration of his authenticity and sincerity. After beginning his political career as a hero to Democrats, Crockett soon fell out with Andrew Jackson over the congressman’s opposition to the Cherokee removal. In 1831, in the midst of his public feud with the president, Crockett himself attended a performance of The Lion of the West in Washington, D.C. His presence authenticated the fictional portrayal, and bound the audience’s entertainment to frontier history and an ongoing political struggle for the soul of the republic. Allegedly he bowed from his box to the delight of a vocal crowd.2 Subsequently, The Lion of the West was rewritten various times, with one version called The Kentuckian, or, a Visit to New York.3 Thus, even before Crockett’s apotheosis at the Alamo, he was a national figure who fused frontier politics, national identity, and popular entertainment. If nobody invoked Crockett at the New York opening of Buffalo Bill, it is hard to believe that old theater hands like Buntline and the renowned dramatist Fred Maeder were unaware of the parallels to Crockett’s 1831 appearance—and harder still to believe that Buntline in particular was not manipulating the evening to reenact it. Subsequently, the novelist took Cody to Philadelphia to meet with his newly founded Patriotic Order of the Sons of America, a nativist organization for whom Buntline hoped Cody would be a symbol.4

In any case, Cody’s attendance at the city theater both announced his arrival in the metropolis and, paradoxically, authenticated him—Crockett-like—as a frontiersman.5 Perhaps with the Tennessean in mind, he toyed with the idea of a political career afterward. A Democrat like his father, he was appointed justice of the peace for a brief tenure at Fort McPherson in 1871. Not long after his return from New York, friends nominated him for a seat in the Nebraska legislature, and he was a candidate in the 1872 elections. In his autobiography and show programs, Cody claimed he won that race, but resigned the seat to go on the stage. In fact, although initial returns showed him winning, the official tally made him a loser by forty-two votes. 6

This supposed election to the legislature became the source of his title “Honorable,” which he emblazoned across his posters and show programs—“The Honorable William F. Cody”—for the rest of his career. His imagined electoral victory placed him in the pantheon of American frontiersmen who rose to civic leadership. If white men were distinguished from savages by their capacity for self-governance, then the humble white frontiersman who rose to elective office was proof both of American upward mobility and of the governing capacity of whiteness itself. Cody’s fake political biography, in this sense, placed him alongside other frontiersmen with more substantial political accomplishments, including not only Crockett, but Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, and even George Washington—all figures to whom Cody would compare himself late in life.7

But as we have seen, Cody had little time for politics. It was the stage that entranced him. Standing before that sea of faces, Cody issued his tongue-tied greeting, bowed, and “beat a hasty retreat into one of the cañons of the stage.”8 Those “cañons of the stage” would become his next frontier, as he ventured onto the boards to play himself before large and mostly enthusiastic audiences.

Resonating with a range of cultural traditions and shifts, the comic story of Cody’s dramatic career probably entertained as many people as his plays ever did. The audacious leap to the stage by a man with no theatrical training appealed to a public which still preferred innate talent, or natural genius, to educated skill. Just as they preferred the militiaman to the professional soldier, in the theater they loved watching the amateur dramatist upstage professional actors. At the same time, as we shall see, the spectacle of Buffalo Bill Cody playing himself also attracted audiences fascinated with copies, mimicry, and theatrical self-presentation, as expressions of industrialism and middle-class imitations of elite culture, and of the increasing acceptability of imposture in everyday social relations.

The catalytic intersection of Cody’s career with these arteries of popular culture began during his visit to New York, and continued in the months afterward, as Buntline importuned Cody to come back to the East and play the role of Buffalo Bill on the stage. Finally, Cody agreed. In the fall of 1872, he left Fort McPherson for Chicago, in the company of his friend and fellow army scout John Burwell “Texas Jack” Omohundro, a Cody acolyte whose ambitious frontier imposture (he began scouting at Cody’s instigation after arriving in Nebraska in 1869) made him even more eager than his mentor to attempt a theatrical career. Buntline was disappointed when the scouts arrived without the genuine Pawnee Indians he had been promoting. For their part, the scouts were horrified to discover that Buntline had not yet written the play in which they were to appear five nights hence. So, too, was the owner of the theater who had agreed to host their show, and after he backed out, Buntline contracted to rent the theater for a week, at a price of $600. As Cody recalled it, Buntline then took them to a hotel, where he sat down to write. Four hours later, he “jumped up from the table, and enthusiastically shouted ‘Hurrah for the Scouts of the Plains!’ That’s the name of the play. The work is done. Hurrah!”9

Buntline directed Cody and Omohundro to “do your level best to have this dead-letter perfect for the rehearsal” the next morning. Doubting that they could learn the lines in less than six months, “we studied hard for an hour or two, but finally gave it up as a bad job, although we had succeeded in committing a small portion to memory.” When Buntline dropped by to hear Cody’s recitation, the scout “began ‘spouting’ what I had learned, but was interrupted by Buntline: ‘Tut! Tut! You’re not saying it right. You must stop at the cue.’

“ ‘Cue! What the mischief do you mean by the cue? I never saw any cue except in a billiard room.’ ”10

When the play opened four days later, General Sheridan and a phalanx of Chicago’s upper crust came to see it, along with rows of mechanics and other laboring men. In the drama, Buntline, as Cale Durg, an old trapper, enters the stage accompanied by his friends Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack. In the first act, they face off against Indians, played by forty or fifty “supernumeraries,” or “supers,” today known as extras. Blasting away with pistols at the supers, they rescue the heroine of the piece, Cale Durg’s ward, a virtuous white woman known as Hazel Eye. In act 2, Mormon Ben, a Latter-day Saint with fifty wives, covets Hazel Eye for his fifty-first. To this end, he schemes with his henchmen, Carl Pretzel, a German, Phelim O’Laugherty, an Irishman constantly in need of a drink, and Sly Mike. All of these were standard melodrama types, the ethnic parody a product of the city’s ethnic and racial tension. Immigrants Pretzel and O’Laugherty are enemies of the home and domestic order, like polygamous Mormons and the Indians in act

1. When Mormon Ben makes off with Hazel Eye, the Indians attack him and recapture her. Shortly before she is to be burned at the stake, her hands are untied by the good Indian maiden, Dove Eye (played by the famous dancer Giuseppina Morlacchi; one critic described Dove Eye as “the beautiful Indian maiden with an Italian accent and a weakness for scouts”), and she is rescued by Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack, who enter shouting, “Death to the Redskins!” and blast away until all are dead. So the action continues, with evil white men (Sly Mike), derelict immigrants (Pretzel and O’Laugherty), and white men so evil their whiteness is questionable (Mormon Ben), allying with bad Indians to steal the beautiful white woman, only to be laid low by the white, native-born scouts’ voluminous gunfire in almost every act. Ultimately, of course, evil is vanquished, Buffalo Bill has Hazel Eye in his arms, and the curtain comes down.11

Plays about frontier history were very popular in the 1870s. These included upmarket productions like Horizon, Across the Continent, and Frank Mayo’s Davy Crockett, all of which were hailed as true American art. 12 But in the case of Buntline’s bloody, action-packed spectacle, the reviewers were condescending when they were not dismissive. Cody recalled one who remarked that “if Buntline had actually spent four hours in writing that play, it was difficult for any one to see what he had been doing all that time.”13 Others noted the woodenness of the frontiersmen, the mostly working-class audience, and the imponderable plot, all brought together by the appearance of the famous dime novelist and the famous scout. “Such a combination of incongruous drama, execrable acting, renowned performers, mixed audience, intolerable stanch, scalping, blood and thunder, is not likely to be vouchsafed to a city a second time, even Chicago.”14

The company toured the Midwest and Northeast the rest of the winter, playing to packed houses. The following year, Cody and Omohundro split with Buntline, and launched out on their own. Omohundro and Morlacchi married in the fall of 1873, and by the following year they had broken away from Cody to form their own theatrical company.

Cody persevered without them. His theatrical company, soon called the Buffalo Bill Combination, toured through the next decade. Consistently, he played the role of Buffalo Bill in frontier melodramas where the unifying theme was the liberation of a virtuous woman from savage captivity and her restoration to her home and family. His popularity was gigantic. So was his monetary reward. In 1880, he took home profits of $50,000. More, Buffalo Bill’s stage career introduced him to formal show business, and was in turn the stage from which he launched his much larger, more complex outdoor spectacle, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show.15

Cody’s fun, of course, entailed tremendous labors on his part, and on the part of his family. Within weeks after Cody’s departure from North Platte in the fall of 1872, Louisa joined him in St. Louis, where Scouts of the Prairie was appearing. She traveled with him throughout the rest of the season, trundling along with their three children: daughter Arta, now six; son Kit Carson, who turned two on the road; and another daughter, Orra Maude, only three months old that fall.16

During the following year, the Cody family relocated to be nearer the theater circuit, moving to a new home in West Chester, Pennsylvania, where William Cody had cousins. But Louisa disliked West Chester. During his divorce trial, William Cody explained that his relatives “were on the Quaker order and she didn’t like their quiet ways, and she was not friendly with them.”17 So Louisa and the children continued to travel with the show. In the fall of 1873, family and theatrical combination set out on the road again, wife and children traveling along with Cody until March of 1874. That month, when the show reached Rochester, New York, Louisa seemed to like the town. “We decided that there would be the best place to take up our residence, as the town was centrally located and I would be more apt to be at Rochester than I would be in most any other town.” 18

Ultimately, the family home again became tangential to Cody’s stage orbit. Tragedy struck in 1876, when five-year-old Kit died of scarlet fever, moments after William Cody arrived home from his show in New York. One wonders if the pain of losing their only boy motivated the Codys to return West. In 1878, Louisa took Arta and Orra back to North Platte, where Will Cody had bought them a house in the now substantial town of stores, churches, farms, and businesses. Stage drama would continue to be Cody’s major occupation through 1883, when he initiated the Wild West show, an entertainment self-consciously modeled on the Plains and for which North Platte would be a central base and point of departure. By that time, he was the leading actor of frontier melodramas and a wealthy man.

IN HIS AUTOBIOGRAPHY and in popular memory, the encounter between mime and man, the actor playing Buffalo Bill and the real Buffalo Bill, became the central narrative moment of Cody’s first New York tour. His theatrics amused crowds partly by calling attention to the uncanny resemblance between the romantic images of him created by writers and actors (Art) and his real self (Nature) and inviting them to separate the two if they could. In this respect, his stage career was a new departure in his now customary, artful juxtaposition of original and copy, a western scout who looked suspiciously similar to his many representations in the popular press.

Audiences in New York, the capital of American theater, first encountered Cody as the “King of Border Men,” in Ned Buntline’s serialized story in the New York Weekly, in December 1869. Any impulse to dismiss him as a simple fiction was complicated by his appearance in New York Times coverage of minor Indian skirmishes in 1870, and then again in reports of the extravagant hunting trips of General Sheridan in 1871, and probably in other news stories which have since been lost.19

Cody’s press reputation was continuing to grow at the very moment that he stepped into New York society. Sometime in 1872 or 1873, William E. Webb’s memoir and western travel guide, Buffalo Land, arrived on book-seller shelves (Webb was the division agent for the Kansas Pacific Railroad who had forced Cody’s town of Rome into oblivion). Although Buffalo Bill appears only briefly in the book, he ambles across Webb’s pages (as across Buntline’s) alongside the not-quite-imaginary Wild Bill Hickok, with the author praising Cody as “spare and wiry in figure, admirably versed in plain lore, and altogether the best guide I ever saw.”20

Cody’s rise to fame was partly a function of the changing mass press. He arrived in the popular eye as newspaper editors hit on the technique of manufacturing news rather than merely reporting it. The master of this strategy was James Gordon Bennett, Jr., publisher of the New York Herald, who was a member of Sheridan’s hunting expedition in 1871, and who that very year sent a former Indian war reporter named Henry Morton Stanley to Africa in search of the “missing” Dr. Livingstone. In the hands of Bennett and his imitators, wilderness scouts, guides, explorers, and explorer-journalists were all manifestations of the white vanguard, conveying civilization to dark and savage places. Readers devoured press accounts in which adventurous journalists themselves increasingly became the subject of “news.” Reports of Stanley’s adventures in Africa, in fact, covered columns of print right alongside coverage of the Grand Duke Alexis’s hunt the following year. For the rest of his life, Buffalo Bill Cody served as a useful story for any writer with a deadline. Not coincidentally, Bennett was one of those who invited Cody to New York and hosted him on his arrival. He had an uncanny nose for a story.21

The grand duke’s hunt provided New Yorkers with their most vivid version of Cody before he arrived in their town. Although his role in the expedition was minor and he was overshadowed by Custer, he received his best coverage in the New York Herald, whose reporter took time out to consider “the genial and daring Buffalo Bill,” a “genuine hero of the Plains.” Even at this point, much of the fun in watching Cody came from his verve in assuming the costume of romantic hero to please the crowd, and his amusement at his own audacity. When the medical doctor attending the Grand Duke Alexis asked Cody if he always dressed in the “spangled buckskin suit” of that morning, related the correspondent, Cody grinned. “No, sir; Not much.” He went on, wrote the reporter: “ ‘When Sheridan told me the Duke was coming I thought I would throw myself on my clothes. I only put on this rig this morning, and half the people in the settlement have been accusing me of putting on airs,’ and then Bill laughed heartily, and so did the Doctor, the Duke, and the whole imperial crowd.” 22

In February, at least two events reminded New Yorkers of the recently completed tour of the grand duke. The first was the debut of a new act, “The Grand Goat Alexis,” at a prominent burlesque theater, in which a goat rode a horse around a ring, with a monkey thrown on his back, “and the horse thus bears a couple of stories of animals round and round the ring, amid the wildest shouts of laughter.”23 The second, of course, was the arrival of Buffalo Bill.

Throughout his visit to New York, his representation in the press and on the stage could be measured against his real person, a kind of interplay between dramatic Cody and real Cody, the former on the stage at the Bowery, the latter frequently sighted in downtown New York, at the Union Club, the Leiderkranz masked ball, and at the fashionable racetracks.

New Yorkers could continue this Cody game even after the man left the city. Almost as soon as he went back to Nebraska, Ned Buntline published a new Buffalo Bill novel, Buffalo Bill’s Best Shot, which continued to work the line between truth and fiction with a romance inspired by the hunt with the Grand Duke Alexis. Even if they passed up the chance to read it, New Yorkers saw announcements of it over three successive days in the New York Times and elsewhere.24

Once he moved onto the stage, Buffalo Bill Cody would be a news staple for the rest of his life, moving back and forth over the line dividing the real and the fake, Nature and Artifice, his stature as a “real westerner” underscoring the interplay of the two. Synopses of his plays and reviews of the dime novels about him appeared in the same newspapers that reported “real” news about his cattle drives at his Nebraska ranch, his guided hunting expeditions with English aristocrats, and his Indian fights across the Plains. To audiences, then, Buffalo Bill’s life was a fascinating mixture of theatrical romance and bloody reality, much like the West itself.25

CODY’S OCCUPATIONS on the Plains had all been tied to the expanding railroad, and his stage stardom, too, was partly a product of the railroad and the ways it revolutionized the theater. In earlier days, a theater owner (often a renowned actor) would hire a company of actors to work in residence, performing plays in repertory for a whole season. After the Civil War, the railroad made sedentary companies obsolete. Now, theatrical stars became the center of companies known as “combinations.” Opening at a prominent theater in New York, usually in early autumn, the combination then went on tour via the nation’s new railroad networks, performing a selection of plays in many different cities and towns. Troupes disbanded at the end of the season, usually in late June. The promoter, or star, could then begin the process of hiring anew and commissioning new plays for the next season. As New York historians have observed, “The city had become a manufacturer of dramatic commodities,” and theater was becoming at least as much an industry as an art.26

Buffalo Bill’s fame grew as he grafted his earlier guiding and scouting persona onto this new form of commodity production. To say the least, the theatrical career was an unlikely turn. “That I, an old scout who had never seen more than twenty or thirty theatrical performances in my life, should think of going upon the stage, was ridiculous in the extreme.” 27 But if the frontiersman’s metamorphosis into stage star seems counterintuitive, in another respect the stage was a fitting venue. Actors, like spies and scouts, were traditionally a marginal class in America. Professional deceivers, they were reviled by the Puritans as liars and blasphemers, and by subsequent generations of Americans for their suspicious facility with disguise. In the many warnings that moralists and urban reformers issued about the confidence man, the theater figured prominently as one of his preferred venues for the introduction of virtuous youth to urban sin and decadence. After all, the confidence man, the consummate seducer, was himself a skilled actor. 28

These prejudices against the theater had weakened considerably by the 1870s, by which time successful actors were no more unpopular than successful lawyers (conversely, low-rent thespians were every bit as reviled as hack attorneys). But suspicion of actors as disreputable and their entertainments as immoral remained a backdrop for Cody’s entire career.29 Nate Salsbury, Cody’s managing partner for many years in the Wild West show, began his show business career as an actor after the Civil War, at which time his cousin warned him that “the majority of the American people think that a man who is talented lowers himself by going on to the stage.”30

Thus, Cody’s new appeal was in some ways analogous to his appeal as a scout. Just as surrounding himself with socially dubious mixed-bloods and Indians made him stand out as a white guide and tracker, by entering the arena of actors—professional impostors—he both compounded the layers of skepticism around his own persona and simultaneously enhanced the currency of his authentic hunting, scouting, and Indian fighting. Meeting a genuine frontiersman who seemed to embody the progress of the nation was one thing, but seeing him in a context of outright fakery, supporting a drama in which he banished the savagery of the frontier, upped the value of his real biography.

Just as important, Cody’s stage debut was not accidental, but a calculated development of his entertainment product. Out on the Plains, the western show that Hickok, Cody, and others crafted for tourists—tall tales, shooting exhibitions, hunting displays, and the projection of a heroic persona in keeping with popular expectations—begged a central question: if the audience was coming west on the train to see the performance, why not put the show on the train and send it east? Showmen had staged frontier exhibitions before. P. T. Barnum’s failed New Jersey buffalo hunt of 1843 was a prime example. The transcontinental railroad made such attempts easier, at least potentially. Thus, in 1872, while Buffalo Bill was visiting New York, museum impresario Sidney Barnett hired Cody’s friend and neighbor in Nebraska, Texas Jack Omohundro. The Texan was to accompany a herd of buffalo and a group of Pawnee Indians to upstate New York, where they would perform a mock buffalo hunt for tourists at Barnett’s museum. Although Omohundro and several others put in much time and effort capturing buffalo, government agents refused to allow the Pawnees to travel east. Texas Jack backed out, too. Nonetheless, the staged hunt went forward. In August of that year, Wild Bill Hickok served as master of ceremonies for Barnett’s show, in which a delegation of cowboys joined a party of Sac and Fox Indians from Oklahoma. The crew performed a mock buffalo pursuit on the grassy foreground of America’s most renowned wilderness monument, Niagara Falls. But the event proved difficult and expensive to stage. Barnett lost money and folded the show.31 Still, few doubted that moving the show of western progress to the East had a future. The question was how to make it happen.

At the time of Hickok’s appearance at Niagara Falls, Cody’s first theatrical performance in Chicago, with Texas Jack Omohundro, was only three months away. Theatrical drama had the advantage of being far more familiar to audiences than the kind of outdoor arena exhibition that Barnett and Hickok were presenting, and on the stage Cody could incorporate rope tricks, shooting displays, and other aspects of western show spectacle which he would one day display in an arena. Read carefully, Cody’s protestations of dramatic ignorance in fact suggest the omnipresence of theater on the frontier, and its familiarity to him. The “old scout” (he was twenty-six) “had never seen more than twenty or thirty theatrical performances.” 32 It might seem a sizable total by today’s standards, but Cody’s estimate was probably low (the better to emphasize the implausibility of his career turn). Frank North, legendary scout and friend of Cody’s, lived in Colville, Nebraska, where he kept a journal during 1869. It was a busy year for the young North family. There was not only a new baby at home, but also a lumber business and rental properties to tend, two major expeditions to fight the Cheyenne, and a social calendar packed with reading circles, dances, and concerts. Nonetheless, Frank North saw fourteen plays at Omaha theaters in 1869 alone.33

Although its inclusiveness had faded in previous decades, theater was traditionally the nation’s foremost democratic entertainment, presenting a large variety of productions for all classes, and in all regions. Even in Iowa, at the time Cody was born, theatrical troupes performed in English and German.34 On the Great Plains, theaters were among the first buildings erected in new towns. Stage drama, in fact, preceded the stages. In Kansas, as on earlier frontiers, soldiers often entertained each other and surrounding settlers with dramatic companies at their posts. Traveling dancers, singers, magicians, jugglers, and acting troupes made their way along the trail to Denver by 1859, frequently stopping to perform in Leavenworth and other Kansas towns.35 Major E. W. Wynkoop, who fought in the Plains Indian wars with Cody in the late 1860s, became founding president of the Amateur Dramatic Association of Denver in 1861.36 Theaters operated in Leavenworth right through the Civil War (the esteemed John Wilkes Booth even appeared there).37

By 1867, William Cody had named his favorite buffalo rifle “Lucretia Borgia.” Some speculate that he heard of the famous Italian poisoner and erotomaniac from the play of the same name, a popular nineteenth-century offering which was showing in St. Louis when Cody was stationed there with the Union army in 1864. But it is just as likely that he saw the play in Denver, where it was playing when the fourteen-year-old Cody was there in the winter of 1860.38 In the Kansas cow towns, minstrel shows and burlesque proliferated, along with opera and melodrama.39 By the time Cody arrived at Fort McPherson, there was a post theater in operation there, too.40

Yet, for all Cody’s exposure to theater as an observer, for him to become a stage actor was a daring move. It was one thing to have seen some plays, and to tell stories and dress in costume for tourists and soldiers in Kansas or Nebraska. It was quite another to interpret a script and entertain a packed house in Chicago, New York, or Memphis. Equally important, after a short apprenticeship with a professional (Buntline had adapted numerous novels for the stage, and occasionally acted himself), Cody somehow mastered management of a theatrical company, too.

His autobiography suggests that he found his bridge to stage acting in his experience as a hunting guide. In his early days with Buntline, he adapted his renowned storytelling to stage performance, filling in his acting gaps with his own narrative drama. On his opening night, when Buntline stepped forward in his role as “Cale Durg” and gave Cody his cue, he later recalled, “for the life of me I could not remember a single word” of the script. Buntline then prompted Cody with a different line, “Where have you been, Bill? What has kept you so long?”

At that moment, Cody noticed in the audience one of Chicago’s renowned wealthy sport hunters who had been on one of the more colorful hunting trips he had guided. “So I said: ‘I have been out on a hunt with Milligan.’ ” Milligan was a leading light of Chicago’s social scene, and the audience roared.

Buntline, never one to stick to a script when a better line appeared, went with the drama Cody was creating: “Well, Bill, tell us about the hunt.” As Cody recounted: “I succeeded in making it rather funny, and I was frequently interrupted by rounds of applause.” Whenever the story wandered off, “Buntline would give me a fresh start, by asking some question.” In this way, Cody wrote, “I took up fifteen minutes, without speaking a word of my part; nor did I speak a word of it the whole evening.”41

ORIGINAL/COPY

Thus Cody extended and recast the drama he staged around the campfires of his guided hunts, finding in the East a vast, lucrative market for his form of entertainment. Only months before, a newspaper correspondent had described Cody’s “wonderful” campfire stories, related “in the presence of all the paraphernalia of frontier life upon the Plains.” On the stage, Cody appropriated the same “paraphernalia of frontier life”—guns, knives, whips, hats, boots, and ropes—and dressed the part, as he had for his hunting clients, in lavish suits of buckskin and velvet and fur, complemented by a broad hat and his hair falling to his shoulders.42

His manipulation of those props was central to his authentic demeanor, and his stage plays called for his character to demonstrate his abilities with gun and whip, with stunts that would one day become part of his Wild West show. “Mr. Cody’s shooting was very fine indeed,” wrote one reviewer in 1879. “He shot an apple from the head of Miss Denier, and then taking a mirror he turned his back to the young lady and shot it from her head again. He also knocked the fire from a cigar which was held in the mouth of Mr. James. His shooting and use of the ‘cow driver’ is simply marvellous.”43

Historians and critics long ago established that Cody’s stage success came from the friction between his frontier authenticity and its context of theatrical fakery. His performance simultaneously validated and called into question his own imposture as a “genuine” frontiersman, delighting audiences who could debate and argue over how “real” Buffalo Bill was. Playwrights often adapted cheap novels for the stage, but in the plays of Buffalo Bill, Texas Jack, and the other stars of frontier melodrama, the heroes were “real” people, and whether or not they believed the hyperbolic publicity, the audience loved the novelty. 44 Thus, the packed houses that greeted Cody, Omohundro, and Buntline in New Haven and other places expressed popular desire to see the heroes they knew from “weekly story papers, and the semi-occasional novelettes” about them, according to a contemporary writer.45 As Roger Hall has observed, “the presence on stage of an actual participant in frontier events reinforced the vicarious and psychological connection of the audience to those events.”46

But to describe Cody as authentic, a self-evidently “real” man conveying elements of the real frontier, only scratches the surface of his allure. Historians have carefully retraced nearly every Cody performance. They have analyzed his few surviving scripts, and pored over his advertising. But exclusive attention to the real William Cody has blinded us to the faux Codys, the numerous actors who continued to play “Buffalo Bill” at the same time William Cody did, and for many of the same crowds. Moreover, in addition to professional actors who struck their own poses as the stage character “Buffalo Bill,” a sizable number of frontier scouts followed Cody to the stage and so closely mimicked Cody’s scout persona as to make audiences wonder who really was the authentic frontiersman.

“It is within an exuberant world of copies that we arrive at our experience of originality,” writes Hillel Schwartz.47 And Cody’s originality was considerably enhanced by the wide mimicry of his imposture, which placed him less at the center of a theater of the original than in the dance of original and copy that defined the essence of frontier melodrama. To be sure, William Cody was Buffalo Bill, and this gave the stage character a purchase in offstage—real—life. But the proliferation of Buffalo Bill impersonators on the stage meant that, in a sense, Buffalo Bill the stage character was both real and fake—and William Cody’s achievement was to encompass both sides of that coin.

The theater of mimicry and copy in Cody’s stage performance might be said to have begun when he confronted Studley playing the Buffalo Bill role. The two together, Studley and Cody, provided poles of fake and real, a simultaneous display of the copy and the original that resonated with popular fascination for such contrasts, notably by providing space to wonder which was which. Was Studley imitating Cody? Or vice versa?

We may speculate that Cody’s continuing presence in New York enhanced the appeal of his stage impersonators by prolonging this tension. The standard run for a new melodrama was two weeks. Studley ran his “Buffalo Bill” for a month. Indeed, immediately after the last curtain fell on Studley’s faux Buffalo Bill at the Bowery, the play opened again, on March 18, at the Park Theater, with J. W. Carroll as its faux Cody. The same day, in a sign of Buffalo Bill’s popularity, a parody—a faux faux Buffalo Bill, called Bill Buffalo, with His Great Buffalo Bull—opened at Hooley’s Opera House, in Brooklyn.48

To audiences, Buffalo Bill balanced somewhere between real man and theatrical representation. By venturing onto the stage himself in the fall of 1872, Cody enhanced the tension that charged the character’s appeal. If the move made him more popular, it also lent frisson to the performances of fake Codys, particularly in New York. At the beginning of the theatrical season, the drama Buffalo Bill played for a week in mid-November, at Wood’s Museum, with James M. Ward in the title role. One month later, New York theatergoers could read news coverage of the real Buffalo Bill’s performances in Chicago, and as Buntline, Cody, and Omohundro toured the Midwest—St. Louis, Cincinnati, Indianapolis, Toledo, Cleveland—the actor J. B. Studley began playing Buffalo Bill again in January of 1873, at New York’s Bowery Theater, and then again during the last week of March at the Park Theatre.49 The news of Cody’s imminent arrival in New York reinforced the appeal of Studley’s Buffalo Bill, making it the advance “bill” for the real Bill.

Studley’s performance closed on March 30. The next evening, the real Cody opened with Buntline and Omohundro in Scouts of the Prairie at Niblo’s Garden, where they played until mid-April.50 Then, following a brief stint at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Cody’s troupe left New York. A month and a half later, the real Cody was touring the workingmen’s theaters of industrial upstate New York, while, back in the city, Studley was in the Cody role again, at the Theatre Comique.51

The compelling entertainment in this concoction of reality and representation came at least in part from its resonance with a fad for playful imitation which permeated late Victorian America. As manufacturing and mass production came to define the American economy, copies of things increasingly replaced real things. The basis of middle-class culture was imitation of elites. Machine production of goods, cheap but realistic imitations of furniture, clothing, and architecture, allowed middle-class people to appropriate elite fashions easily. Mimicry and copy thus became central to middle-class life.52

In this context, self-styled arbiters of taste like Edith Wharton hewed to the authentic, but to most people, the empowerment of imitation was too great to ignore. If copies of authentic goods allowed middle-class people to express equality with elites on the cheap, why not celebrate imitation? In this spirit, middle-class people intentionally confused the fake and the real as a form of cultural play, turning the imitation into a category of its own. The most daring imitations were those that crossed the line between Nature and Art, mimicking the one with the other. Thus, many middle-class parlors displayed paper flowers mingled with real flowers, wax or marble fruit in bowls of real fruit, real ivy (grown from cuttings in a bottle of water) climbing wallpaper on which were printed realistic ivy patterns, and iron furniture shaped like twigs and branches. This interpolation of fake and real proliferated across American living rooms, a new aesthetic that created enjoyment by fooling the senses, simultaneously celebrating industrial mass production and domesticating it within the parlor, and honoring the skill of the decorator.53

In its cultural implications, it went far beyond living room decor, expressing the playful, entertaining mixture of trick and truth behind the period’s most popular entertainment, the artful deception. It also resonated with the most successful plays and novels, which explored mimicry, doubles, disguises, and imposture at length. Henry James was fascinated with imitation in middle-class life, and Mark Twain’s parade of double identities, fakes, and tall tales wound through every one of his books from Roughing It and Huckleberry Finn to Life on the Mississippi and his own autobiography. 54

Reviews of Buffalo Bill plays are too sparse and fragmentary to allow us insight into the fascinating give-and-take between the real man and his stage imitators. Were there actors who played Buffalo Bill more convincingly than Cody did? We cannot know, but the bait-and-switch of fake and real in the Cody game amounted to playful deception which mimicked and lampooned the more serious deceptions of commerce. Advertisements for dramas starring Cody and Omohundro appeared in long lists of ads for other commodities—umbrellas, skin cream, hair dye, and hats—with the ubiquitous call to brand loyalty, “Accept No Substitutes.” Where New Yorkers had to select the best and most effective products from a host of imitators, the frontier melodrama turned the parade of real and fake into a harmless entertainment. Perhaps there were loyalists who believed Cody was the only acceptable “Buffalo Bill.” But the continuing popularity of the faux Codys suggests that for audiences, the real Cody was a kind of substitute after all, a stand-in for the dramatic Cody popularized by J. B. Studley and others. A sip of distilled authenticity was refreshing, but the cocktail of dramatic actor and historical actor was what made the show fun. J. B. Studley played Buffalo Bill again in October of 1876, his performance again the “advance Bill” for the real Bill Cody, who appeared in Scouts of the Plains in Brooklyn the following week.55 Frank Dowd (or Doud) played Buffalo Bill at the Theatre Comique early in the summer of 1877; William Cody played in May Cody, or Lost and Won, at the Bowery Theater at summer’s end. 56 Stage mimicry of Buffalo Bill continued even after his stage career ended. As late as 1891, during the peak years of his Wild West show fame, vaudeville theaters were performing short comic plays about his life, such as Buffalo Bill Abroad and at Home, their outrageous fakery a counterpoint to his avowed authenticity.57

But in the late 1870s, professional actors cooled to the role of Buffalo Bill, and by the 1880s, Buffalo Bill stage plays sans the actual William Cody were the exclusive domain of cheap variety theaters. The waning popularity of Cody’s professional imitators can be traced in some degree to the emergence of at least a half-dozen other frontiersmen claiming to be “authentic” scouts, each appearing in melodramas with frontier themes, constituting a genre of performance that Cody’s publicist, John M. Burke, called “the scout business.”58

Although punctuated by the rhetoric of reality, and purveyed by scouts who were themselves symbols of authenticity, the scout business provided mimicry more subtle and entrancing than even the alternating appearance of fake and real Codys. So many scouts moved onto the stage, inspiring so many dime novels and ever more stage plays, that professional actors were no longer necessary to carry off the impression that somebody was being imitated, and somebody might be real. In fact, the genre of frontier melodrama that Cody kicked off spawned so many “real” frontier heroes playing themselves, so thoroughly appropriating the props, gestures, scripts, and even the biographies of one another, that the stars of the entertainment could be seen alternately—or simultaneously—as “genuine” heroes and as imitations of one another. Thus, in October 1874, Donald McKay, an army scout in California’s Modoc War, appeared in a play about the life of Kit Carson, alongside a troupe alleged to consist of real Warm Springs Indians. One month later, McKay himself became the subject of Donald Mackay, a play in which actor Oliver Doud Byron played the California scout.59

There were others. After Cody and Omohundro split with Buntline, the novelist persuaded another resident of North Platte, by this time a primary staging area for western imposture, to take his show east. Thus, Charles “Dashing Charlie” Emmett, a scout for the Second Cavalry, starred as himself in a Buntline play apparently based on the life of scout Frank North. LittleRifle, or, The White Spirit of the Pawnees was successful enough that Emmett took the drama with him when he, too, split with Buntline. Venturing out to impersonate himself (or was it Frank North?) in stage plays, he was buoyed by the company of esteemed actress Alice Placide.60 Emmett played New York City in the spring of 1874, and assisted Cody with a benefit performance in November. Emmett’s Little Rifle followed on the heels of Byron’s Donald Mackay at Wood’s Museum the same month.61

How much the scout business was predicated on scouts imitating one another, to be imitated in turn by actors who sometimes claimed to be “real” western heroes, can be seen in the twisted tale of representation surrounding Cody’s mentor in artful deception, Wild Bill Hickok. As we have seen already, Cody imitated Hickok in his early days, appropriating elements of his biography, such as spying in the Civil War. On the stage, Cody continued to work the Hickok vein. In his first stage appearance, Buffalo Bill fought “Jake McKanlass,” loosely based on one of Hickok’s real-life victims, Dave McCanles, with a bowie knife. By 1874, he was parroting some of Hickok’s other tall tales, claiming to have ridden for the Pony Express. By casting himself and Hickok in Scouts of the Prairie in 1873, he upped the ante in the contest between fakery and reality, with two scouts named Bill who looked and dressed very much alike, each an “original” western hero.

According to Cody, the role of Wild Bill Hickok became a prominent one for professional actors, too, sometimes in unconventional ways. Where scouts represented themselves on the stage and off, professional actors—or confidence men—sometimes took to representing themselves as scouts, both on the stage and off. Thus, Cody relates that after Wild Bill Hickok’s brief tour with his company in 1873–74, a rival stage company hired an actor to play the role of Hickok onstage, and to impersonate the gunfighter in public venues such as restaurants, saloons, and on the street. In Cody’s account, the last stage appearance of the real Wild Bill Hickok was when he leapt onto the boards and thrashed this impostor in front of a packed house, just before returning to the West.62

Whether or not Cody’s Hickok tale was apocryphal, it captures the heightened tension between fakery and reality that energized frontier melodrama to its core. Before frontier melodrama emerged as its own subgenre, the standard melodrama’s devotion to disguises and masks, with villains, heroes, and long-lost children continually donning new faces and new identities, was central to its appeal for audiences consumed with the artistry of imitation. The obvious impostures provided dramatic irony, allowing the audience insight into the action that the characters did not have, resolving it when the masks came off at drama’s end.63

The story of Hickok in the theater, punching the daylights out of somebody mimicking him, suggests how much the stars of frontier melodrama not only parodied all drama but also performed parodies within parodies. At times, the scouts in the dramas were so similar as to be almost interchangeable, and the genre threatened to swallow the “authentic” men who succeeded in it. There were two Jacks, “Texas Jack” and John “Captain Jack” Crawford (the latter emerged quickly on Omohundro’s coattails in the mid-1870s). To the consternation of both men, audiences and seasoned show troupers alike often confused them.64 Paradoxically, this was an appeal of the frontier or “border” drama. As the number of “real” scouts in “true” border dramas multiplied, myriad variations on the theme of authenticity and fakery permeated the action, making the typical masks and clumsy disguises of ordinary melodrama seem tame by comparison.

Buffalo Bill endured longest in the genre, and came to stand as its most “authentic” product. For this reason, scouts and actors who sought bona fides as frontiersmen attached themselves in one way or another to him. But in fact, he developed his own character by borrowing freely from others, particularly Hickok. For two years, in 1875 and ’76, Cody played the lead in a play originally written for the lawman, Wild Bill, or Life on the Border. Because so many people confused Cody and Hickok anyway, few members of the audience probably realized that he wasn’t the play’s title character. But even if they were ignorant of Buffalo Bill’s imitation of Wild Bill, the play contains dizzying twists on the theme of reality and fakery that pervaded the frontier melodramatic genre. The action swirls around counterfeiters who disguise themselves as Indians. Thus, the real scout plays a scout, opposite actors who play villains who fake Indians who fake money. 65

The denouement of the play resolves the many tensions between the fake and the real in favor of the latter. The character of Bill Cody apprehends the malingerers, and rescues George Reynolds—the father of Cody’s love interest, Emma Reynolds—who has been kidnapped by the counterfeiters. In the end, the counterfeit ceases: the white men no longer play Indians, and they no longer make false money. The true scout, Buffalo Bill, whose fidelity is reinforced by the fact that he is “playing” himself, finds “true” love with virtuous Emma, the “true woman.”

Not all of the mimicry attached to the scout business was playful. On occasion, it veered into fraud, which posed real dangers for the leading lights of the scout business. For the game of authentic-and-copy to work, for audiences to enjoy the artistry of imitation, somebody had to be “the real thing,” that standard of reality against which the imitation could be judged. Cody’s prospects hinged on retaining his status as the “real” Buffalo Bill. Should he lose his grip on that role, there was no other for him. He was not a professional actor.

In this sense, offstage impersonators posed a threat, something Hickok appears to have understood in his violent reaction to his impostor, and something Cody and Omohundro had to confront as well. After their first season together, Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack began carrying endorsements from military officers and western acquaintances, something that they each continued to do throughout their stage careers, because fraudulent theatrical companies, featuring actors claiming to be them, often traveled ahead of their own troupes.66

In other cases, actors who played scouts in productions featuring real scouts like Cody and Omohundro would branch out on their own, trying to sell themselves as authentic frontiersmen. When Texas Jack took a break from the Buffalo Bill Combination in 1874, Cody temporarily replaced him with an actor. His identity remains a mystery, but he appeared as—and claimed to be—Kit Carson, Jr. Mustered out of the company on Omohundro’s return in 1875, he formed his own stage company and set out to make a name for himself in the scout business.67

The efforts of Kit Carson, Jr., were in vain. His combination failed. 68 But he infuriated Cody, a fact that suggests how serious a matter imitation and impersonation could become for the stars of frontier melodrama. The business was fiercely competitive, with so many scouts qua actors and actors qua scouts that enduring as the chief draw required constant attention not only to stage production, but to authentic frontier exploits as well. Cody’s entire stage career depended on his remaining the figure that other figures were imitating, even if much of his stage persona was a skillful imitation of other scouts, like Wild Bill Hickok, and, possibly, of other actors as well. We may assume that it was for this reason that Cody, who regularly made more in a week at the theater than he took home in a whole season of scouting, returned to the West to scout for the army in 1874, on the Big Horn expedition, and again in 1876, as the Great Sioux War burst upon the northern Plains.69

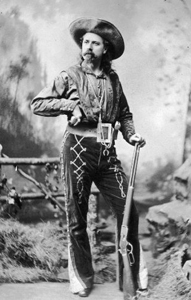

Cody in the stage outfit of black velvet and silver trim in which he killed Yellow Hair (whose name was mistranslated as Yellow Hand). Cody’s the atricalism in Indian war had everything to do with the competitiveness of frontier melodrama. Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

His careful attention to theatrical trappings in the scalping of Yellow Hair had everything to do with the endless one-upmanship of the scout business. Indeed, Cody’s attention to theatrical effect in the killing (his costume, his shout “First scalp for Custer!”) and his realism in staging it (same costume, same shout—and the real scalp, too) entangled event and performance so thoroughly that historians and Cody partisans would debate for decades whether the killing was real or somehow faked. The movement of the encounter from battlefield to stage was so smooth that at least one man swore the enmity between Cody and Yellow Hair actually began in the theater. In 1936, longtime Rochester resident Robert Hicks told historian A. E. Sheldon that Cody had hired Yellow Hair for his stage combination in 1874, but one night Buffalo Bill flattened him with a roundhouse when the Cheyenne drank too much and began insulting ladies backstage. At that moment, claimed the alleged eyewitness, Yellow Hair swore vengeance, and the feud culminated two years later, at Warbonnet Creek.70

In fact, Cody knew the frustrations of Indian fighting well enough to know, the moment he heard that Custer had fallen, that the Indian wars finally had a genuine battlefield martyr, a figure who would stand for the U.S. Army’s conquest of the Plains the way Stonewall Jackson had stood for the Confederate cause in the Civil War. By becoming Custer’s authentic avenger, shedding symbolic first blood and returning with the scalp to the eastern stage, Cody could claim to be the embodiment of the frontier hero, the white Indian who ventures over the line between civilization and savagery to vanquish evil by adapting savage methods, and then ventures back, without ever compromising his innate nobility.71

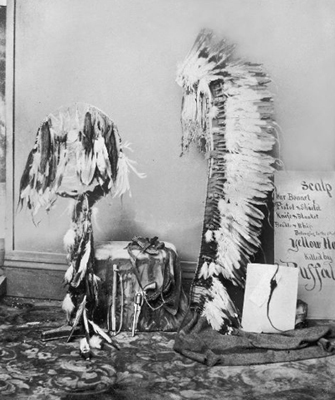

But timing was as important as symbolism. News of Custer’s death hit the nation’s newspapers on July 4. The Fifth Cavalry was in the field and did not hear till July 7. On July 18, Cody wrote to Louisa that he had taken Yellow Hair’s scalp, and a few days later he sent the scalp, warbonnet, shield, and other trappings to Rochester, where they were displayed in the window of a friend’s shop, with a large poster explaining that Buffalo Bill had killed and scalped Yellow Hair in revenge for Custer’s death. On July 23, the New York Herald ran the story of the Cody–Yellow Hair fight.72 Buffalo Bill became not only Custer’s avenger, but the first of those avengers. All others were imitations. Accept No Substitutes.

Yellow Hair’s belongings, on display in a Rochester, New York, storefront. Cody displayed them in the lobbies of theaters, too, but many condemned the practice. Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

In 1877, Cody’s publicist, John Burke, noted privately, and in his typically cascading prose, that “Bill has had every advantage that could possibly assist a man, from the Sioux stirring up a stink, to poor Custer’s misfortune, and Yellow Hand’s [sic] unfortunate accident, with the hirsute incident, a ‘custom more honored in the breach than in the observance’ but very efficient in working up the ‘bauble reputation.’ ”73 Yellow Hair’s scalp became Cody’s trademark, distinguishing him in the scout business so effectively that other scouts’ attempts to mark their own authenticity always seemed to mimic his. The futility of competing with Cody’s brand of authenticity was perhaps most apparent to John “Captain Jack” Crawford, the self-styled “Poet Scout,” who starred briefly in Cody’s combination in 1877–78 before going on to a lifelong rivalry with Buffalo Bill. Crawford was an Irish immigrant and Civil War veteran who emigrated from Pennsylvania to the Black Hills of Dakota Territory in 1874 (a move which may have been inspired by watching Cody’s theatrical troupe perform in his hometown of Pottsville, Pennsylvania, in 1873).74 Crawford became a correspondent for the Omaha Bee and an early settler at Custer City, Dakota Territory, where he set himself up as captain of his own company of volunteer scouts at the beginning of the Sioux War of 1876. Cody met up with Crawford during his scout forays that summer, and threw him an assist by recommending him to the military command as his own replacement when he left the Plains in August.75

Cody’s authenticity as scout and race hero was such that when the war against the Sioux continued in 1877, he did not bother to join. Crawford signed on as scout for the army again, and his military career culminated at the battle of Slim Buttes, where many of the Sioux who vanquished Custer were finally subdued. Crawford was reported to have killed and scalped a Sioux warrior during the battle. But, whether it was because of his own reticence about the deed or his inability to attach a name to his victim, or because it was too much a copy of Cody’s “original” act of the year before, as a publicity device the scalp proved of limited use in his subsequent theatrical career.76

In the fall of 1877, Crawford joined Cody’s stage troupe, playing Yellow Hair in the reenactment of the fight on Warbonnet Creek. Seriously injured in a stage mishap, he soon decided to form his own theatrical company, letting it be known that he felt abandoned and manipulated by Buffalo Bill. Cody was angry and told Crawford that “had the accident not occurred I think you had [already] made up your mind to start out for yourself.” Cody’s ire suggests how jealously he guarded his own authentic status, but it also hints at how difficult the scout business was. “People have flattered you until you think . . . that you are a great man. Jack, go ahead,” Cody urged. “You will find out that all that glitters is not gold.” 77 Nonetheless, Cody would not try to stop him. “I wish you success and I will never do a thing to hurt you.” The two men remained friends, but Crawford’s jealousy at Cody’s success made him bitter as old age approached. In bringing Buffalo Bill to stage stardom, he wrote on one occasion, “Ned Buntline created the most selfish and brutal fake hero ever perpetrated on the American people.”78 Crawford’s accusations notwithstanding, the fakery of Buffalo Bill paled beside the fakery of his many imitators, like Crawford, whose jealousy and mimicry of Cody only enhanced Buffalo Bill’s claim to being “the real thing.”

LIVING THE STORY

All stage art is a mimicry of real life, but the scout business so confused the categories of real and fake, action and mimicry, that to one New York Times correspondent it seemed to presage a new kind of theater, the “Drama of the Future,” which would “illustrate current history through the painting of actual events, by the real actors in them.” This new art form would “call upon the conspicuous personages of current history, on getting through each marked phase of their careers, to have dramas written describing the same, and go about playing star engagements in the chief character.” Of course, there was a real danger that people would (as Cody did, especially in the case of Yellow Hair) deliberately seek “strange adventures” or even court “deadly perils,” all “with the idea of acquiring attractive material for a success on the boards.” Nonetheless, “the lives of most people are already more histrionic than they think”—or admit. There were, after all, “infinitely more actors and actresses in real life than there can possibly be on the stage.”79

If the “Drama of the Future” never materialized, if those occasions of real people playing scenes from their own life remained the exception and not the rule, in truth the stage plays of Buffalo Bill did not much resemble it, anyway. Although the Scouts of the Prairie, Knight of the Plains, and the other Buffalo Bill dramas pretended to mimic Cody’s real life, they were elaborate, expansive fictions. Their story lines featured plenty of references to actual people, including the Grand Duke Alexis, Cody’s younger sister May, Texas Jack, Wild Bill Hickok, and, of course, Buffalo Bill himself. But beyond these simple allusions, the plays bore almost no relation to Cody’s real life. He never foiled a ring of counterfeiters who were dressing as Indians, he never fought Jake McKanlass, or anybody with a similar name, and he never rescued his sister May from Mormons.

The trick of being the “real” Buffalo Bill was, of course, to tie his biography to his stage performances and lend them authentic resonance, especially when they were untrue, which was almost always. Thus, in May Cody, or Lost and Won, his sister is abducted by Mormon patriarch John D. Lee during the historical Mormon attack on an emigrant wagon train at Mountain Meadows. Her brother, Buffalo Bill, disguises himself as an Indian and rescues her. But before they can celebrate, he is arrested at Fort Bridger, and put on trial for being a spy. Ultimately, he is exonerated and the play reaches its happy ending.80

The play was written by Major Andrew Burt, an army officer and friend of Cody’s. Like other melodramas and like most dime novels, too, it was a response to recent news events, in this case the 1877 execution of Mormon patriarch John D. Lee for his part in the notorious Mountain Meadows massacre twenty years before. William Cody never claimed that his sister had actually been abducted, but it was at this time that he began to claim that as a boy he had been on a wagon train that was raided by Mormons and forced to retreat to Fort Bridger, and this tall tale became a prominent story in his autobiography, which he published two years later.81 For every real event which Cody acted out on the stage, his plays featured dozens that never happened at all. Rather than a drama in which historical people acted out their real accomplishments, Cody’s melodramas were more often fictional tales which he appropriated as “true” after starring in them.

Such revelations raise other questions—notably, if Cody was making dramatic fictions into his autobiography, why didn’t anybody call him on it? Why did audiences seem unable, or unwilling, to recognize the deception? The answer hinges on the role of the West in melodramatic imagination. The Far West and its peoples were still remote enough that audiences first encountered them through the press. Correspondents like George Ward Nichols and Ned Buntline interpreted the lives of Hickok, Cody, and Omohundro through the lenses of dime novels and melodramas, and often by resorting to the tropes of the genre. The mythology of progress which western events seemed to validate, the clearly visible ascent of civilization, was easily incorporated into melodramas of frontier heroes restoring virtuous women to domestic bliss—which, in the workings of melodrama, was the heart of civilization itself. Melodrama idealized domesticity. In play after play, the melodrama reinscribed the notion that personal happiness, democracy, the future of the republic, and just about every other desirable condition depended on domestic contentment, which in turn depended on chaste marriage, and of course, the “true” and unstained woman. Just as the triumph of civilization over savagery was understood as the triumph of domestic order, the salvation of the settler’s cabin, so the melodrama’s core plot was the rescue of the virtuous woman and her restoration to the home.82

Thus, audiences projected melodramatic fantasies onto Hickok, Cody, and Omohundro even before they saw their plays, envisioned them saving white women from Indians even before they “saw” them do just that on the stage. The heroes’ appearance in these theatrical performances authenticated the fantasy. Just as important, these figures could continue taking part in the real, offstage adventure of western progress, their exploits perpetuating the blend of authentic and fantastic. Thus, throughout their careers in the public eye, stage scouts sought to embody western progress by carrying on high-profile, self-consciously progressive lives in the offstage West. In addition to fighting Indians through 1876, Cody launched into ranching in northern Nebraska. Omohundro, Crawford, and Hickok sought profits in mining companies.83 In each case, they entered industries which represented progress, the coming of pastoralism or industry to the savage wilderness. Each skillfully avoided, or avoided publicizing, other ventures less materially tied to progressive mythology, such as managing railroad or stage lines, or opening yet another business in one of the many western towns where saloons, barbershops, and dry goods stores proliferated. Cody turned down an officer’s commission in the army.84 Tellingly, none became a farmer in the 1870s, as if the culmination of progress—the redemption of the garden from the wilderness—was too much denouement and insufficiently compelling for the drama they sought to play out. Thus, they inscribed the forward motion of civilization, the advancement of progress, into their life stories. They proved the myth true, thereby heightening the authenticity of the very fictional plays they showed each theatrical season.

Absent the mythology of progress to play out in his offstage life, the stage character of Buffalo Bill might have vanished after brief popularity, or perhaps gone on to become an entirely fictional character, with no appreciable tie to the real William Cody. Such a trajectory obtained in earlier cases of real people represented on the stage. In 1848, New York playwright Benjamin Baker created the character of a heroic fireman named Mose. The character was based on a real person, Mose Humphrey, a typesetter for the New York Sun and a volunteer firefighter renowned among the newspaper workers who crowded theater galleries. Represented by a popular actor, Francis “Frank” Chanfrau, who had grown up in the Bowery himself, Mose became a huge draw for theaters. Because he was a “real” person, the character could not be copyrighted. Thus, after 1848, Mose cropped up in numerous novels (at least one of them by Ned Buntline) and plays (at one point, Chanfrau played Mose in two different productions playing simultaneously at rival theaters). Before long, Mose became a kind of folk hero, a Paul Bunyan of Manhattan, who was said to have jumped across the Hudson, to have blown ships back down the East River, and to have carried a streetcar with the horses dangling. 85

But by that time, he was no longer attached to his inspiration, the real-life fireman. We may speculate that this separation between myth and man would likely have occurred even if Mose Humphrey had stepped into the role to play himself. After all, firemen were heroes, but they did not represent a moment in a larger progress, except in the most abstract sense. Cody, the hunter and Indian fighter, had initiated the rise of civilization in the West. The mythology was so self-evidently “true” that it played on the stage as well as it supposedly “played” in the West. Theoretically, he could spend his remaining years living out the subsequent stages of civilization’s ascent as rancher, farmer, patrician, and revered town founder. Indeed, that is precisely what he attempted to do.

He had more options than people like Mose Humphrey. For the machinists, typesetters, artists, firemen, clerks, and doctors who might have played themselves onstage, the real challenge was less that their lives had no drama than that they could not infuse their offstage lives with the narrative that western progress conveyed, and which made the continuing appearances of western scouts, especially William Cody, so interesting for theatrical audiences. Melodramatic fantasy was harder to sustain around “real” figures from other regions because regional history either fit less comfortably into the mythology of ascendant civilization, or because that history was too remote. There were dramas aplenty about southern life, including wave after wave of Uncle Tom’s Cabin reprises. But southern history, with its descent into slavery, read more like American-history-gone-wrong. White southerners were too associated with slave owning to allow a single progressive hero to champion the region’s regressive story. Northern history was easier to narrate as heroic saga, but its moment of redemption from wilderness was far enough back in time that its protagonists were long since dead.

Frontier melodrama had no such constraints. Its core stories were the rise of white civilization and the restoration of domestic bliss. As a narrative it was vague enough not to offend and yet it resonated with a broad range of urban and small-town concerns, including the need for a civil order, for the protection of the family from hostile forces, and for the continuing dominance of white men in a society ever more diversified by waves of immigration. Indians were too alienated from the civil order to object to dramatic misrepresentation. The melodrama’s white and immigrant villains, bent on miscegenation and thievery, went far beyond the bounds of defensible behavior. The frontier’s centrality to American ideas of history and progress provided not just a theory of American development, but a powerful story about how people behave and how events unfold. The advancement from primitive hunting to modern commerce, from savage disorder to enlightened civilization, provided a ready-made narrative, a backstory, to every drama set there. In other words, audience expectations of frontier stories were so powerful that they could look past the blatant fiction of these dramas and embrace the “real” frontier heroes as proof that their expectations and assumptions about the frontier were mostly true.

In one more sense did the frontier West have an advantage as a setting that combined real people and mock play: the frontier line had long served as a mythical dividing point between fakery and reality. Frontier melodrama’s mixture of fakery and real people was so compelling because the West itself was synonymous with that same mixture. The West was, in a word, a humbug, and if the drama that presented it most truthfully was itself an artful deception, the West in the 1870s, with its many boosters making impossible but still alluring claims for its promise, had itself become an apt symbol for the fakery and irresistibility of the theater, the locus of the actor’s outrageous claims and seductive power.

MIDDLE-CLASS SYMBOL, WORKING-CLASS HERO

If the New York Times correspondent who predicted the “Drama of the Future” was mostly incorrect about the future shape of American drama, in one respect the prediction expressed a popular, little-appreciated idea which made Cody’s stage appearances so satisfying. By asserting that there were “infinitely more actors and actresses in real life than there can possibly be on the stage,” the correspondent touched on pervasive concerns about the imposture of modern living in the 1870s. The interchangeability of original and copy was an entertaining parody of mass production and consumer fashion, but the scout business also resonated with even broader cultural trends toward the acceptance of ordinary people as imitators, or actors, in day-today living. Superficially, Buffalo Bill, Texas Jack, and the other protagonists of frontier melodrama offered a critique of theater by eschewing the title of actor, as if to reinforce traditional prejudice against actors and theatrical drama. “They do not pretend to be actors, i.e. ‘Buffalo Bill’ or ‘Texas Jack,’ ” wrote one critic; “they simply present to the view of an audience scenes in actual border life, similar to those which they themselves have passed.”86 The deception that he was an actual man, not an actor, was a consistent feature of Cody’s career, and a decade later he continued the pretense. “I’m not an actor—I’m a star,” he told an interviewer in 1882. “All actors can become stars,” he explained, “but all stars cannot become actors.” 87

The success of the untrained “anti-actor” in a domain of trained professionals was, in a sense, a series of elbow jabs to the ribs, an ongoing inside joke between him and his fans, who adored him less for his acting than for his willingness to send up professional theater itself. Stage drama, after all, depends on a pact between actor and audience: one pretends, the other pretends to believe. By refusing the title of actor, Cody announced his inability to pretend—then went on the stage anyway, as if to say that acting was for professionals, but imitating actors was the domain of the natural man. In this sense, his presence on the stage was a parody of the entire theatrical industry.

If the real Cody was no actor, it followed that he was incapable of disguising himself. There was no veil to come off. But once the novelty of seeing Buffalo Bill onstage diminished after the first couple of seasons, Cody began commissioning playwrights to layer more complex impersonations on top of his stage identity, and the character of Buffalo Bill began to take up more complex disguises. In Cody’s 1878 production, The Knight of the Plains, his character assumed three different identities: an English nobleman, a detective, and a Pony Express rider.88 The “real” William Cody was now assuming new masks which fooled other characters, but not the audience.

The effect was less to renounce acting than to embrace it. Professional thespians in the drama relied on Cody’s presence to make these dramas work. They had to pretend to be tricked by his unlikely disguises. The play within the play reinforced the larger message of Cody’s stage career: any man can pretend, act, manipulate the professionals, and succeed. White American manliness and imposture were not antithetical. Manly men took to acting like frontiersmen to the wilderness.

Imitations of the “real” Buffalo Bill were one source of Cody’s success; the enthusiastic reception of this message—that all white men can be actors—suggests another. Theater was by no means universally respected in the 1870s, but it was accruing acceptance as Americans came to see it as a reflection of new forms of social interaction. The rapidly accumulating wealth of the middle classes in the second half of the nineteenth century led to new forms of conspicuous display, and the development of industrial production placed ever less emphasis on traditional yeomanry and ever more on sales and marketing as pathways to wealth and respectability. Where they had once aspired to a society in which Christian trust was pervasive and one’s intentions were self-evident, increasingly Americans “were learning to place confidence in more elaborate forms of self-presentation,” in the words of scholar Karen Halttunen.89 Americans had begun to see their own dependence on manners and middle-class facades as a kind of theater of everyday life. This was the reason for the rising popularity of “parlor theatricals,” elaborate, amateur productions with curtains, painted sets, prompters, dramatic lighting, and a full array of props. Across the country, urban middle-class people staged these shows for friends and neighbors in their living rooms. Such displays expressed middle-class dependence on—and confidence in—complicated manners and social rituals to explain themselves. The message of the parlor theatrical was, essentially, “Life is a charade.”90

In no small measure, Buffalo Bill embodied and expressed the everyday American’s facility for theatrical display and upward mobility. Thus, Buffalo Bill’s character was not just the exclusive purview of Cody or his professional imitators. Middle-class men across the country took to playing Cody, just like real actors, in parlor theatricals. In 1874, out at Fort Abraham Lincoln, in Dakota Territory, that icon of middle-class manhood, George Armstrong Custer, played the role of Buffalo Bill in his elaborate living room production of Buffalo Bill and His Bride, with Libbie as his leading lady.91

Whether or not P. T. Barnum ever saw Buffalo Bill’s stage plays, they provided the requisite mix of authenticity and imposture of his own entertainments. Indeed, contemporaries remarked on the similarity between Cody’s new art and Barnum’s. Back in Nebraska, in her cabin not far from Fort McPherson, Ena Raymonde, a friend of Cody and Omohundro, read reviews of their stage appearances in the fall of 1872. “Verily, life is a humbug, ” she mused, “and he that is the biggest humbug, has the best chance for humbugging the rest of his fellows.”92

On the frontier, indeed, Buffalo Bill was an object of fascination and dispute. Locals argued about him and Texas Jack much as they argued over Hickok and other artists of western imposture. But his success at integrating himself into the mythology of the West as an icon of middle-class theatricality made him a favorite symbol for settlers by the early 1870s, in ways that Hickok, teetering between lawman and outlaw, could never be. Locals in the vicinity of Fort McPherson ordered Cody’s portrait photo from the photographer in North Platte. Ena Raymonde took the time to hand-tint hers.93 Participants at an 1872 masquerade ball in Wichita, Kansas, ordered their masks from Kansas City. Among the visages that evening were a Spanish cavalier, the goddess of liberty, Satan, and Buffalo Bill.94

It may be, as one scholar has argued, that “personal conduct in societies based on the premise of upward mobility is characterized by a highly theatrical presentation of self.”95 In which case, Cody’s appeal as a symbol of theatrical self-presentation, a man who played his “real” self in the theater, was all the more central to his age. So what prompted him to leave the stage after over a decade of astounding success? Why take a risk on a bold new entertainment like the Wild West show, which was so unlike the stage in its size, complexity, and dramatic messages?

In fact, there were reasons aplenty, beginning with the ways the limited appeal of the theater eventually constrained Buffalo Bill’s marketability. Antitheatricalism had declined, and the “respectable” middle classes no longer shunned all theaters as disreputable. But theater performances usually appealed to one class or another, and critics encoded the class composition of audiences in their reviews. In general, middle-class, white-collar men would not take their families to productions patronized by working-class men (where prostitutes and lower-class women could also be found). On the other hand, respectable theaters were generally too expensive for middle-class people, and they grew more expensive as the century progressed. “By the mid-1880s,” says David Nasaw, “the average theater ticket cost a dollar, two-thirds of what the nonfarm worker earned in a day.” Most city residents simply could not afford such prices.96 Urban nightlife was ever more the domain of wealthy young sports who had enough fiscal and social capital to afford its corruptions, and lower-class workers, many of them immigrants, who guzzled beer in the concert saloons and vaudeville theaters of the day.97 Museums, which banned drink and prostitution, were more acceptable entertainment venues. But most working- and middle-class people had few or no affordable, reputable nighttime entertainment venues. 98

Cody had worked hard to restore himself to the middle class after the Civil War. He kept the middle-class company of officers and entrepreneurs in Kansas and Nebraska, and in Rochester his daughters went to private school, and the Cody family lived in a well-to-do, tree-lined district. As a public figure, he was symbolic of middle-class entertainment with his seamless moves between real guiding, hunting, and Indian fighting and his fictional representations of those same activities.

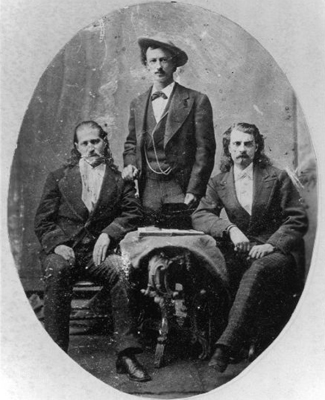

The Cody family—Arta, Orra, Louisa, and William Cody—as middle-class bastion, c. 1880. The theatrical melodrama seldom drew the crowd to match Cody’s aspirations to respectability. Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center.