CHAPTER NINE

Domesticating the Wild West

THE FIRST-EVER dress rehearsal of the Wild West show occurred in 1883, at Colville, Nebraska, the home of Frank North and the Pawnees who made up the show’s Indian contingent that year. According to eyewitness L. O. Leonard, when the Deadwood stagecoach trundled into the arena, Buffalo Bill invited the town council, including the mayor, a beloved but notorious blusterer named “Pap” Clothier, to ride in the coach. For the first two passes around the showgrounds, the coach rolled merrily along, and its occupants waved to the crowd.

On the third pass, the Pawnees swept into the arena. The coach passengers were expecting it, but “the mules had not been advised of this part of the program, nor had they been trained to Indian massacre.” The animals surged forward, the Indians in hot pursuit, the driver barely able to keep the coach’s wheels on the ground as it rounded the turn. When Buffalo Bill and his cowboys suddenly went into the action as the rescue party, nobody had told the Indians to break off the attack. Terrified by several dozen howling men on horseback and the thunder of guns, the mules stepped up the pace. “As the coach, Indians, scouts, and Cody swept past the crowd again, the mayor stuck his head out the window, waved his hands frantically, and shouted, “Stop: Hell: stop—let us out.”

But the driver had all he could do to keep the stage on its circular course without rolling it over. The mules did not halt until they were thoroughly winded. At that point, the enraged mayor “leaped out of the coach and made for Buffalo Bill, ready for a fight.”

Fortunately, before Clothier could reach Cody, a local wit named Frank Evors climbed to the top of the coach. “Look at them, gentlemen.” Pointing to the dazed town council and the infuriated mayor, Evors declaimed his pride in these men who “risked their lives . . . for your entertainment.” Clothier now turned back to the coach and went after Evors, who escaped. Meanwhile, Frank North rode up to Cody with some advice: “Bill, if you want to make this damned show go, you do not need me or my Indians. . . . You want about twenty old bucks. Fix them up with all the paint and feathers on the market. Use some old hack horses and hack driver. To make it go you want a show of illusion not realism.”1

In an era riven with concern over the bawdy or otherwise “unsuitable” content of public amusements, the dress rehearsal was an inauspicious beginning for an entertainment Cody hoped would “catch the better class of people.” 2 He was hunting for the elusive treasure sought by many other entertainers: middle-class women, and the family audiences their patronage assured. Thus he had a dilemma on his hands.3 A tamer spectacle was necessary. However, the Wild West show’s commitment to borderline violence— gunplay, horse breaking, and other physically dangerous performances—was central to its attraction as a “true” picture of “life in the Far West.”

From 1883 until its last days, the authenticity of Wild West performers was a major audience draw. In many ways, the show’s high-speed simulacrum of combat, animal mastery, and marksmanship was a spectacle of “real” historical actors whose virility was a bulwark against the artificiality and decadence of modern civilization. Throughout the 1870s, on his forays as hunting guide, Cody had crafted himself as an antidote to the anxieties of city sports seeking manly restoration in wilderness pursuits. In the 1880s, his show addressed an emergent and popular obsession with the supposed decay of American civilization. True, Americans celebrated westward expansion in literature and paintings on the theme “Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way” (a line from an eighteenth-century poem by Bishop George Berkeley, on the inevitability of civilization’s westward march). Some of these paintings were appropriated and mimicked in the colorful posters of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. But Americans of the Gilded Age were also highly conscious of what we might call the law of social gravity: a society that traveled up the arc of progress must eventually come down.4 The popular rationale for Indian wars had been the need to restrain savage passions and advance the cause of progress. But as the Indian wars ended, the very restraining hand of civilization seemed to be “overcivilizing” white American manhood, snuffing it out, burdening masculine energies until they became perverted and feminized.

The most coherent statement of these popular fears came in 1880, when the physician George M. Beard catalogued a host of symptoms for what he identified as a new malady in his book, American Nervousness. In company with many other medical professionals of his day, Beard saw an epidemic of strange anxieties gripping American men, including extraordinary “desire for stimulants and narcotics . . . fear of responsibility, of open places or closed places, fear of society, fear of being alone, fear of fears, fear of contamination, fear of everything, deficient mental control, lack of decision in trifling matters, and hopelessness.”5 He gathered these disparate, neurotic symptoms under the rubric of a single illness, which he gave the name “neurasthenia.” In his view, neurasthenia afflicted the civilized whose work required “labor of the brain over that of the muscles.” Thus its most common victims were white, middle- and upper-class businessmen and professionals. Overtaxed by commercial and managerial demands, their neurasthenic bodies were rendered “small and feeble.” An epidemic brought on by the civilizing process run amok, neurasthenia represented something more than a psychological condition. By undermining virility, it endangered the future of the white race and its civilization. In Beard’s words, “there is not enough force left” in neurasthenics “to reproduce the species or go through the process of reproducing the species.”6

The impact of Beard’s work was widespread, and the specter of neurasthenia subverting and corrupting white America aggravated other racial fears that became pronounced in the 1880s. Immigration from Germany, Ireland, and other northern European countries had provoked social anxiety and political upheaval for over a generation when the river of immigrants suddenly acquired new tributaries. In the decade following 1880, almost a million, mostly Catholic and Jewish, immigrants from southern and eastern Europe joined the nearly four million from western and northern Europe. Increasingly, the proportion of Slavs, Russian Jews, Italians, Poles, and other eastern and southern Europeans surpassed that of northern Europeans.7

Since the days in the 1840s, when Ned Buntline rallied his first anti-immigrant mob, native-born Americans had feared their Anglo-Saxon, Protestant republic was becoming a polyglot nation. The so-called “new immigration” ramped up those fears. To many observers, the new immigrants were base savages, like Indians. Although their large numbers of children proved their biological fertility, they were short on “manly” attributes such as sobriety, thrift, and self-control. The United States was in the process of becoming an urban nation even without the new immigrants. After the Civil War, native-born Americans migrated to the cities in such numbers that by 1920 the farmer’s republic was truly a thing of the past. But the cities that were coming to define American life were also immigrant bastions, especially in the tenement districts teeming with crime, squalor, poverty, and vice. If the cities were the future, they were also a savage frontier poised to swallow white America.

At this moment of urban peril, the other frontier, in the Far West, finally closed. With the U.S. Census Bureau’s 1890 declaration that the frontier no longer existed, a defining condition of American life blinked out. Cultural and political responses ranged from attempts to preserve wilderness landscapes in national parks to elegiac paintings and novels. The gathering sense that the future would be more urban, less natural, more corporate, and less individualistic pervaded American culture.8

In cultural terms, frontier and city had long been mirrors which reflected and sometimes inverted each other. Many saw urban disorder as displaced frontier savagery. As the cities grew larger and more diverse, and as the frontier receded further into memory, Americans adapted the rhetoric of frontier conquest to metropolitan problems. Beginning in 1886, urban reformers, many of them educated women, sought to domesticate what they called the “city wilderness” through the establishment and administration of “settlement houses.” These were centers providing immigrants with child care and with education in the rudiments of civility, including the English language, civics, the arts, and personal hygiene. Situated in the most “savage” urban districts, they were in a sense an urban analogue to frontier missions among the Indians. 9

At the same time, artists and writers increasingly—and paradoxically— presented white virtues as products of frontier struggle and the westward movement of Anglo-Saxondom. The shift ran counter to frontier realities, of course. Throughout the nineteenth century, miscegenated scouts, Mexicans, “half-breed” renegades, Indian captivity, and traditions of intermarriage among settlers and Indians had contributed to an image of the frontier as a place of sexual decadence and racial decay. The Americans who actually conquered the polyglot West, as we have seen, included a multiracial, multi-ethnic army, Indian and mixed-blood auxiliaries, and a diverse group of settlers, too.

But now, at least in the minds of many thinkers, the relatively empty spaces of the trans-Missouri West became a final, fading crucible of whiteness which stood in gleaming contrast to the mongrel city. Frederic Remington, a Yale dropout who was born and raised in rural New York state, first went west in 1881, when he took a temporary job on a Montana ranch. He became one of the most influential and dyspeptic artists of the era, his oil-painted, vanishing West an antidote to a modern, degenerate America that was overrun with “Jews, Injuns, Chinamen, Italians, Huns—the rubbish of the earth I hate.” His fantasies verged on ethnic cleansing. “I’ve got some Winchesters and when the massacring begins, I can get my share of ’em, and what’s more, I will. . . . Our race is full of sentiment. We’ve got the rinsin’s, the scourin’s, and the Devil’s lavings to come to us and be men—something they haven’t been, most of them, these hundreds of years.”10

Whether depicting eastern strike or Indian war, Remington’s sketches, paintings, and essays (including images and musings on Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show) were suffused with a sense that white American racial strengths were frontier virtues, and that they were about to be lost amid rapidly multiplying and unmanly immigrants.11 He had much company in these views. While immigrants soared in numbers, the declining fecundity of native-born Americans furrowed the brows of social observers. As early as 1865, the state census chief for New York concluded that there was “no natural increase in population among the families descended from the early settlers.” In 1869, another observer noted the speed with which Americans and Europeans alike were pouring into the cities. “But the most important change of all,” he concluded, “is the increasing proportion of children of a foreign descent, compared with the relative decrease of those of strictly American origin.”12

By the 1880s, the persistence of these trends and the rising consciousness of neurasthenia culminated in a pervasive fear of the eclipse of the white race. The year after Buffalo Bill’s Wild West debuted, Theodore Roosevelt fled his home on Long Island for a ranch in Dakota Territory. When he returned, in 1886, he reentered New York politics and began his six-volume Winning of the West, a paean to the racial vigor of western pioneers which foreshadowed his call to “the strenuous life” for white men, and his reservations about birth control as “race suicide” for white people.13 Although Americans came to admire Remington and Roosevelt as authentic westerners, the two men were decidedly late in exploring the region and its cultural resonances. Their assumption of western identities, as cowboy artist and cowboy president, respectively, followed partly in the tradition of frontier imposture pioneered decades before by William Cody and others.

But the resort to the West as a bastion of white America suggests how the Wild West show (which both Remington and Roosevelt patronized), as it debuted in 1883, anticipated and expressed wider cultural preoccupations with the decay of white manliness. Before long its publicists began to explain it this way, and by 1894 audiences had entered the spirit of the thing. Ogling a show cowboy in Brooklyn, a member of the Women’s Professional League of New York exclaimed, “Those are the kind of men that excite my admiration. . . . Big, strong, bronzed fellows! How much superior they are to the spindle-shanked, eye-glassed dudes!”14

Frontier originals who had subdued the savage wilderness, the Wild West show’s “real” men at once reenacted their exploits and fought a defensive withdrawal before advancing artifice, civilized decadence, and the new immigration. At the very moment when psychologist G. Stanley Hall and others were beginning to suggest innoculating Anglo-Saxons against the epidemic of overcivilization by cultivating the violent tendencies of boys, Cody’s show so convincingly enacted “the drama of existence” that, in comparison, wrote one journalist, “all the operas in the world appear like pretty playthings for emasculated children.”15

The manly hysteria of these reviews, with their ongoing critique of mainstream, middle-class culture as castrated, immature, and sentimental, suggests that as much as the Wild West show expressed anxieties over racial decay and the new immigration, it was also part of gathering cultural reaction against the cult of domesticity. The virtues of home and woman were central themes in American culture, and settlement houses were only a hint of future possibilities for womanly public reform. Many social critics looked to woman suffrage as a means to broaden women’s influence. When Buffalo Bill’s new show played Chicago in 1883, it overlapped with the annual convention of the National Association for the Advancement of Women, whose president, Julia Ward Howe, gave one of many addresses on the reformist potential of women voters.16

To put it mildly, the suffrage movement had critics. Behind the era’s many warnings about overcivilization, neurasthenic collapse, and immigrant takeover of American cities, there lurked a barely concealed revulsion at women’s gathering influence. The early Wild West show, in its ardent appeal to masculine, undomesticated emotions, expressed a gathering backlash against the influence of women in literature, theater, and public life. Frederic Remington construed his lust for race war as a healthy corrective to the plague of womanly sentiment. In literature and ultimately in film, such ideas would culminate in the supremely anti-domestic genre of the Western, beginning with Owen Wister’s novel, The Virginian, in 1902.17

Scholars of western film have penned some of the most trenchant analyses of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. According to its most influential historian, the appeal of Buffalo Bill’s spectacle lay in its antidomestic presentation of race war as a solution to the unruliness of cities and savage labor unrest. With Indians standing in for immigrant strikers, and cowboys and cavalry representing the ruling class, the show was a bloodthirsty, reactionary drama. When the Indians slaughtered Custer’s cavalry in the arena, and Buffalo Bill took his revenge on Yellow Hair, the spectacle implied that violence against all savages, be they Indians or immigrants, was not only necessary, but a hallowed American tradition.18

Such grim interpretations of the show have some merit, as we shall see. But in 1883, Wister’s novel and the birth of “the western” were a full twenty years away. Domesticity yet reigned as a virtue and the bedrock of civilization. Americans of all classes were deeply divided over how best to respond to the era’s frequent and sometimes violent confrontations between strikers, factory owners, and the forces of the law. To succeed as middle-class entertainment, Cody’s new show would have to appeal across a divided political spectrum. Within a few short years, it did. Wild West show audiences included right-leaning fans like Remington and Roosevelt. But as we shall see, prominent reformers and leftists could also be found there. And, vastly outnumbering all these, there were many middle-class women and families, too.

The key to Cody’s achievement in making a mass entertainment out of frontier myth was less in his depiction of racial hostility and free-flowing blood than in the way he framed his spectacle’s violence to make it a show that middle-class women could attend. Only through their patronage could he attract their children and their husbands, too. Much as Cody sought a new kind of manly entertainment to escape the bonds of melodrama, the raucous Nebraska dress rehearsal suggested that drawing “the better class of people” might require reassuring the audience of his show’s safety and good order. It might require, in other words, a restraining hand.

Cody’s previous biographers and Wild West show historians have been loath to trace his tailoring of show attractions to suit his audience, perhaps because so many people claimed to have originated show attractions, and because he left few written clues to his performance ideas. But Cody himself originated most of the show’s central features, and he retained creative control over its performances for its entire life. Despite what Frank North is alleged to have said to Cody at the Wild West show’s first dress rehearsal— “You want a show of illusion, not realism”—there was less of a barrier between the two categories of experience than we might think. “Realism” has had many meanings, but in terms of visual art, in this period it referred to a mixture of fact and affect in ways that were convincing even if they were not truthful to every detail. In other words, it evoked an emotional response through artful deception. Thus, many “realistic” portrait photographs contained painted backdrops of forests or mountains. Viewers knew that these were studio portraits with landscape paintings in them. Nonetheless, they acclaimed them as realistic because they supposedly conveyed the rugged character of the individual being photographed, whether he was Teddy Roosevelt, William Cody, or an Omaha dentist.19

Working from the rough 1883 beginnings, Cody retained the illusion of realism, to such a degree that not only were fans impressed with the show’s authenticity, but even the artist Max Bachmann would call William Cody “the pioneer of realism in American Art,” an accolade which is as indicative of his show’s popular reception as it is overstated. Cody’s achievement was to temper the show’s warrior ethos, making it acceptable to a broad public riven with doubt and discord over the urban, industrial future.20 As much as Americans sought refuge in the mythic West as a masculine space, they remained anxious to protect the home—and civilization—as a bulwark against violence and unbridled passion.

How then, could Americans become domestic, leave the frontier in the past, and yet avoid neurasthenia? How could they retain frontier virtues amid civilization, without decaying into effeminacy or savagery? These were questions which preoccupied Americans, and with which Cody and his managers grappled as they embarked on their new enterprise. If the Wild West show began drawing rave reviews for its express virility only three years after its disastrous dress rehearsal, it did so by containing that virility within a framework of historical progress that culminated in household order. During its most successful years, the show’s embrace of race war was balanced by its display of national progress through family and hearth. As Cody was to discover, before the Wild West show could succeed, it had to be domesticated.

CODY’S NEW “ENTERTAINMENT,” as he described it in early 1883, would not “smack of a show or circus.” It would “be on a high toned basis,” and would consist of “representations of life in the far west by the originals themselves.”21 Cody had been projecting an artfully deceptive persona and biography for at least fifteen years. Now, with the help of his talented publicist, John Burke, he distilled his bricolage of feat and fiction into show publicity. The primary vehicles of Cody’s publicists were colorful posters and show programs, which were pamphlets running into dozens of closely typed pages, with text that explained the “historic reality” of each show scene and introduced the biographies of the principals. According to the small booklet audiences purchased for a dime, Cody was a “genuine specimen of Western manhood.” A “celebrated Pony Express rider” who became a Nebraska legislator and defeated scout William Comstock in a legendary buffalo-killing contest, he had guided William Sherman on his expedition to negotiate a treaty with the Comanches and the Kiowas (a mission actually performed by Hickok, not Cody), and in serving with the Fifth Cavalry he achieved “intimate associations and contact with” a slew of army officers, including “the late-lamented Gen. Custer.” Buffalo Bill stood before the masses as the embodiment of an idealized life story.22

The seam between truth and fiction, fake exploits and real deeds, was so artfully sewn as to be all but invisible. In a sense, Buffalo Bill was an inversion of a Barnum exhibit, the stitching of his deception culminating not in some freakish monkey-fish or ape-man, but a consummate American man who embodied the progressive mythology of the frontier. Audiences could pick and choose what they were willing to believe, and some were never convinced that Cody was everything he claimed to be. The New York DramaticNews referred to Cody as “Blufferblo Bull.”

Indeed, doubts about Cody’s history on the frontier followed him throughout his career with the Wild West show, and rumors circulated that he merely lifted the identity of Buffalo Bill from its rightful owner. Some of Cody’s Plains contemporaries even advanced such a case. In 1894, his old rival Captain Jack Crawford introduced a newspaper reporter to “the real Buffalo Bill,” one William Mathewson of Wichita, Kansas. A former hide hunter who had become a prominent banker, Mathewson had indeed been one of many to claim the “Buffalo Bill” name before Cody did. Now, he alleged that Cody was nothing but his former employee and grandiose imitator. The subject created a stir in the press. Although Cody’s long list of military endorsements and his reputation as a worthy entertainer allowed him to ignore the charges, rumors persisted of some more genuine Buffalo Bill, out there in the West, or perhaps only in memory. But for most, the continuing questions about Cody’s history and identity made his convincing imposture all the more remarkable—and amusing. “He is a poseur,” wrote one reviewer, “but he poses impeccably.”23

So with most spectators. Even when they detected the fakery, it was mixed so skillfully with Cody’s bona fides as an Indian fighter, buffalo hunter, and scout, so thoroughly obscured by his reputation as an experienced entertainer, and so widely imitated by other impresarios that the emphasis on “originals” took on a double meaning, with Cody once again at the center of a playful interchange of real and fake that quickly outdistanced the tired formulas of the frontier melodrama. Buffalo Bill’s performers were the standard from which so many copies were struck that Wild West shows became a subindustry within the larger industry of public amusements, and by 1884 newpapers were already referring to the genre as “Buffalo Bill shows.”24 Cody’s many imitators, such as Gordon “Pawnee Bill” Lillie, Nevada Ned, and “Mexican Joe” Shelley, tailored life stories to resemble his, cultivated an appearance like his, assembled similar shows, and in the case of Samuel Franklin Cody (real name: Franklin Samuel Cowdery) even pirated his name, all of which reinforced William Cody’s reputation as initiator of frontier simulacrum, the “original” Wild Westerner.25

Among the real westerners on display in the show arena, the most original frontiersmen of all were Indians, who, as indigenous primitives, represented the untamed passions which middle-class audiences feared and, increasingly, coveted. In Cody’s earliest plans for the show, Indians were its primary attraction. Even before he had hired any cowboys, Cody wrote to the secretary of the interior about recruiting the best-known Indian of the age. “I am going to try hard to get old Sitting Bull,” he told his partner. The most famous surviving Sioux chief from the battle of the Little Big Horn was a powerful symbol of Indian resistance and savage passion. Only in 1881 had he returned from Canada, where he took refuge after the death of Custer. “If we can manage to get him our ever lasting fortune is made.”26

But the Indian office judged Sitting Bull too dangerous to be allowed off the reservation. Cody turned to the Pawnees. They had done fine work for his stage show, and he hired Frank North, the commander of the battalion of Pawnee scouts, to recruit them.27

Leadership of the new company was another matter. In the spring of 1882, Cody had discussed the idea of partnership in this new venture with actor-manager Nate Salsbury. But that fall, Cody first approached William “Doc” Carver about becoming his partner. Carver was a dentist who had left his home in Illinois and moved to North Platte, Nebraska, in 1872. He bought 160 acres of land on the banks of Medicine Creek, but forsook farming for the vigorous industry of frontier imposture. He practiced marksmanship fervently, sported broad-brim hats and beaded buckskins like the most flamboyant scouts. The Sioux became the subject of his most outrageous lie, in which they allegedly abducted him as a child but eventually became so impressed with his marksmanship, and so fearful of his lust for revenge against them, that they nicknamed him “Evil Spirit of the Plains.” 28

Just as Cody entwined his life fictions with Hickok’s myth, “Evil Spirit” embroidered his with Cody’s. He actually met Cody for the first time in 1874, when Buffalo Bill guided Carver and a party of sports on a hunting trip in Nebraska.29 Soon after, Carver began claiming that he and Buffalo Bill were old friends who had hunted together for years, with Carver (here turning Cody into his own William Comstock) proving himself the superior marksman and champion buffalo hunter of the world.

Cody also approached Salsbury again, but the latter wanted no part of a show with Carver, whom he considered “a fakir in the show business” and who had a reputation for primping (Cody himself had said that Carver “went West on a piano stool”).30

Another critic had said that Carver “had sunk a lead mine trying to learn to shoot.”31 But if that was true, Carver learned, indeed. At his 1878 New York debut (where Texas Jack threw targets for him), he demonstrated marvelous accuracy and endurance, using a rifle to shatter 5,500 airborne glass balls in under 500 minutes. Afterward, Carver’s shoulder was so sore he could barely move, and his eyes burned for days. 32 Subsequently, he ventured to Europe for several years, where he won shooting titles, awards, and much public acclaim. Upon his return, he billed himself as “Champion Shot of the World.”33

Carver later claimed that he originated all of the ideas for the Wild West show, but Cody’s letters to him indicate otherwise. Cody rejected Carver’s proposed names for the show—“Cowboy and Indian Combination” and “Yellowstone Combination”—because, as he warned Carver, “the word combination is so old and so many shows use it.” Cody was looking for a “smooth high-toned name” which “will be more apt to catch the better class of people.” He suggested “Cody & Carver’s Golden West,” and ultimately the two settled on a longer name, but one that reflected Cody’s vision of this amusement as less a “show” than a place: Buffalo Bill and Doc Carver’s Wild West, Rocky Mountain and Prairie Exhibition. Throughout the long life of this entertainment, Cody and his managers refused to call it a show, preferring to emphasize its educational value with the word “exhibition.” The word gave it a veneer of middle-class respectability, and offered audiences a way of attending without fear of being corrupted by the notoriously decadent world of show and theater. From its first year, journalists called it “The Wild West.”34

On a range of other issues, Cody issued directives and Carver followed them, or tried to, including orders to have his picture taken, and then retaken, with his buckskin suit taken in (Carver liked his suit baggy, and it made him look shapeless), posters made in a particular way, orders to check into having an electric generator for night performances (“it will make many a dollar if it can be worked”), orders to have illustrations made for their extensive show program, to follow up on Cody’s negotiations for use of showgrounds in Omaha and Chicago and for the show’s passage on the railroads.35

As the dress rehearsal implied, the all-male cast of the Wild West show, fronted by two masculine stars, pushed the show’s male energies to the limit. But in this earliest attempt to fulfill popular longings for white heroes, Cody actually overlooked certain traditional ideals of frontier manliness. In American culture, ideal men such as frontier heroes were supposed to balance a preponderance of manly strengths with some womanly virtues. The frontier line, in this sense, was not only an imaginary divide between wilderness and settlement, the man’s space of the outdoors and the woman’s space of the house. It was also the border between male and female characteristics in one person. Frontier heroes balanced the (manly) fearlessness of the savage with the (womanly) restraint of the civilized, and in consequence, contemporary descriptions of them are so gender-bending as to strike modern readers as twisted, or even queer. Thus, Wild Bill Hickok’s admirers noted that he had “the shoulders of a Hercules with the waist of a girl,” that the deadly man’s eyes were “as gentle as a woman’s,” and that “in truth, the woman nature seems prominent throughout, and you would not believe that you were looking into eyes that have pointed the way to death to hundreds of men.”36

Similarly, an 1872 columnist covering the hunt with the Grand Duke Alexis described the heroic, virile Buffalo Bill as possessed of “a smile as honest and sweet as that of a love sick maiden.”37 Melodrama, with its emphasis on the salvation of true womanhood and the civilizing influence of domestic harmony, had been an appropriate vehicle for Cody’s stardom precisely because it placed his masculine form in a larger context of feminine virtues. An 1879 interviewer began his description of Cody as flat-out manly—“Tall, straight as a straight line, with magnificent breadth of chest”—then introduced female attributes: “small hands evidently of great power, a remarkably handsome though almost girlish face, hair of which a woman might be proud, and a soft melodious voice.” 38

Cody’s new extravaganza being an effort to escape the confines of melodrama, its first incarnation abandoned any pretense of domesticity or womanly restraint. Neither Cody nor Carver was much of a manager, and both demanded treatment as stars. Their incompatibility was heightened by the fact that both were masculine sharpshooters, symbolically violent figureheads for a show of race war and high-speed horseback pursuits, the whole infused with copious amounts of gunpowder and testosterone.

The masculine figureheads led a cast that was entirely, raucously male. Like other westerners, North Platte locals bragged about and bet on their shooting, horse breaking, and steer roping. By 1883, the town had been home to most of the nation’s frontier melodrama stars and many of the “real” dime novel characters, including not only Cody, but also Charles “The White Chief” Belden (who was stationed at Fort McPherson shortly before he was killed in 1870), Texas Jack Omohundro, “Dashing Charlie” Emmett, John Y. Nelson, and of course Doc Carver. Plenty of other locals wanted their chance at frontier imposture. For the first season, Cody and Carver hired a raft of them. These included William Levi “Buck” Taylor, a six-foot-five Texas cowboy who first rode up the trails to Nebraska with a herd of cattle for the Cody-North Ranch on the Dismal River in 1879. Once he signed on with the Wild West show, he took a starring role in frontier melodrama during the off-season, touring with Buffalo Bill’s Dutchman and Prairie Waif Combination in 1885–86, and he ultimately became the subject of several dime novels.39

Con Groner, billed in Wild West show publicity as “the Cow-Boy Sheriff of the Platte,” had been county sheriff in North Platte since the early 1870s. He was also a physically large man who was said to have apprehended Jesse James (although he had not).40 In addition to Frank North, the impresarios also brought in cowboys from the ranches of western Nebraska, including Jim “Kid” Willoughby, Jim Mitchell, Tom Webb, and roughly two dozen others.

The show consisted of three categories of acts: races, “historical” scenes, and demonstrations of “real” or “natural” skill, that is, talent derived from workplace necessity, not for entertainment (like the circus). This last category including bronco riding, rope demonstrations, and shooting acts. After opening with a parade of Indians and cowboys, along with elk and buffalo, the action began. The first act was an Indian horse race, with as many as ten Indian competitors. It was followed by a reenactment of the Pony Express, “in which the riding and changing of saddle covers was done with startling rapidity,” according to one reviewer. Next came the attack on the stagecoach, followed by a race between an Indian runner and an Indian horseman (with a turn at fifty yards, it was actually close). Together, these scenes suggested the speed of Indians—and the necessary speed of settlers in outracing them.

If any observers had anticipated another circus, by this point, they knew the Wild West show was different. In American culture, the presence of Indians had long implied the presence of history. 41 By featuring them in patently “historical” scenes with actual props from western history—the Pony Express mochila, or mail saddle, and the Deadwood coach—the showmen sent a message that this spectacle was neither an “ethnological congress”—a display of exotic primitives adjunct to a menagerie—nor a mere circus-style display of peculiar skills and speed.42 In Cody and Carver’s arena, foot- and horse races established the central ethos of the show as competition, and the overtly historical scenes—the Pony Express and the pursuit of the Deadwood stagecoach—emplotted the performance with American history, here depicted as a grand race, or a running battle, between Indians, whites, and Mexicans.

These initial racing and historical acts were followed by shooting demonstrations by Buffalo Bill, Doc Carver, and Adam Bogardus, a former market hunter from Illinois who had set many records for competitive pigeon shooting and who was also the developer of the clay pigeon. Seeking to persuade the audience that shooting competitions were more than frivolous or destructive, show publicity transformed guns from implements of destruction to regenerative and constructive tools of frontier development. After all, claimed the program, the bullet was “the pioneer of civilization,” which “has gone hand in hand with the axe that cleared the forest, and with the family bible and the school book.” Without the gun, warned the program, “we of America would not be to-day in the possession of a free and united country, and mighty in our strength.”43

Beyond its relevance to martial exploits and the “clearing” of the frontier, the sharpshooting of Cody, Carver, and Bogardus was a feat of industrial might that inscribed guns as technological wonders and their operators as almost superhuman masters of machinery. Recounting Carver’s first New York shooting exhibition, the program explained that during the 7 hours and 36 minutes in which he performed, “he raised to his shoulder 62,120 pounds, or 311⁄8 tons in weight,” and while working the lever of his rifle, “he moved 248,480 pounds with the middle finger of his right hand.” Throughout, he “withstood from the recoil an aggregate weight of 298,176 pounds,” or 149 tons.44 The machinery of the gun thus empowered the marksman in unprecedented ways, energizing him to move prodigious amounts of matter and allowing him to innoculate the audience against the epidemic of nervous exhaustion which plagued American manhood.

Such feats of martial skill and technological mastery were followed by primitive scenes of the white race’s skill at domesticating nature, the “Cowboys Frolic,” in which cowboys rode bucking broncos, and then roped, threw, and momentarily rode Texas steers. Later in the season, they added displays of “picking up.” The penultimate scene, the “Buffalo Chase,” in which cowboys drove buffalo toward the crowd before turning them back to their corral, reinforced the message of the second half of the show: that white male mastery of technology (guns) and of nature (horses, cattle, and buffalo) was self-perpetuating and total. The last act, a furious ride around the arena by the Pawnees, closed the show with a scene of wild nature and real Indians, as if to say that the challenges of conquering the frontier remained, even though Indians were now defeated. The show would go on, redomesticating the wild nature within it in every performance. 45

Much as this New World historical pageant steered away from the Old World circus, Buffalo Bill’s “thoroughbred Nebraska show” deployed a unifying symbolic device that was ancient and European: the centaur. To sit a horse “like a centaur” was a socially respectable aspiration in the nineteenth century, suggesting a command over animals and manly bearing in the saddle, and comparisons of riders to centaurs was a ubiquitous cliché. In the first season, show programs hailed Buck Taylor as “the Centaur Ranchman of the Plains.”46

But the most famous centaur in the show was, of course, Buffalo Bill himself. He provided the central historical actor—the authentic American—for the show’s display of history. Beyond his symbolic role, though, it was not clear what Cody would do in the arena. He soon carved out his performance space. When Doc Carver left the crowd restive one day by missing every one of his targets, Cody brought them to their feet by mounting his horse and galloping around the ring, blasting amber balls thrown into the air by an assistant.47 On this day and ever after, he—like other sharpshooters in the show—used birdshot in his rifle, because bullets would have traveled beyond the arena and potentially inflicted damage or casualties. But even so, the feat displayed extraordinary marksmanship. The act was quickly installed as a regular attraction, with Cody labeled “America’s Practical All-Round-Shot.”

Even without a gun, Cody evoked a wondrous commentary with his riding. In the urban centers where the Wild West show found its most enthusiastic audiences, streets were jammed with horse-drawn vehicles, but few people rode horses, and most urban residents probably never learned to ride. By the 1880s, horseback riding was mostly an elite leisure pursuit, and the image of a single man on a horse evoked memories of a noble, rural past. 48

Partly for this reason, and partly through his mastery of the gun, which infused him with martial power, the sight of Buffalo Bill on a horse left audiences breathless. Buffalo Bill “rides his horse as if he were a part of the animal,” wrote an 1885 columnist, and in 1886, New York journalist Nym Crinkle called Cody “the complete restoration of the Centaur.” Crinkle’s imagery was so potent that in future years it was reprinted or plagiarized by English publishers, American writers, and Wild West show press agents (who may, in fact, have originated the idea and given it to Crinkle).

“The Complete Restoration of the Centaur.” Buffalo Bill Cody on horseback, c. 1887. Viewed through a portable “stereoscope,” images like these allowed families to view three-dimensional scenes of the Wild West show and savor Cody’s centaurism in the comfort of their own living rooms. Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

No one that I ever saw so adequately fulfils to the eye all the conditions of picturesque beauty, absolute grace and perfect identity with his animal. If an artist or riding master had wanted to mould a living ideal of romantic equestrianship, containing in outline and action, the mien of Harry of Navarre, the Americanism of Custer, the automatic majesty of the Indian and the untutored cussedness of the cowboy, he would have measured Buffalo Bill in the saddle.49

London journalists referred to the Wild West show as a gathering of “Transatlantic Centaurs,” and even before Cody’s arrival in London for the first time, Punch magazine hailed him as “the Coming Centaur.” 50 The centaur reappeared in E. E. Cummings’s 1917 tribute to Buffalo Bill on horseback, shattering onetwothreefourfive pigeonsjustlike that

Jesus he was a handsome man.51

As the mythical creature that marks the ultimate limit between culture and nature, the centaur was in many ways the perfect vehicle for an exposition of frontier life. In the words of one scholar, the centaur represents “the beast within man erupting,” or “the division within man between unreasoning, homicidal monster and angel.”52 The creature’s hybridity—the upper body of a man with the body of a stallion—highlighted its virility. Centaurs of myth were notoriously unreasonable, their masculine lusts and combative instincts overwhelming their human faculties. They were profoundly undomestic, even antidomestic, preferring open spaces and the forest to the constraints of home. They were creatures uncontained, and notoriously unhoused.53

Through inclusion in a spectacle of race war, the centaur symbol acquired additional layers of meaning. Indians, “savage centaurs,” most approximated the horse-men of myth. The show’s white centaurs, Cody and the cowboys, embodied reasoning attributes of masculinity combined with the stallion’s virility and power. Their presence suggested the need for an infusion of natural power—horse power—into white men to ameliorate their loss of nerve force, declining virility, and other symptoms of overcivilization. Just as the Pony Expressman of earlier decades had come to symbolize the monstrous fusion of polyglot frontier and white manhood, Cody’s centaur, and the ranks of centaurs in the Wild West show, represented not only the domination of the West’s wild nature by Americans, but also the reinvigoration of the white race. Thus, the show’s centaurism complemented the efforts of such organizations and developments as the Boy Scouts, the YMCA, the Boone and Crockett Club, collegiate athletics, and much of the broader conservation movement to instill in American manhood some approximation of natural vigor—what Theodore Roosevelt would call the “strenuous life”—to fend off the neurasthenic effects of modern business and the city.54

Cody’s monstrous fusion of horse and man arrived in the East to announce the triumph of civilization and the regeneration of white men and the white race through frontier conflict and technological progress. Where Carver mastered the machine of the gun, Cody’s shattering of amber balls from the air with a rifle as he raced around the arena on horseback naturalized the violent technology of the gun through his mastery of the horse. If the image of Buffalo Bill as Winchester-toting centaur heightened Cody’s masculine image in particular—“Jesus he was a handsome man”—it did so in part by connecting that image to a progressive narrative of white Americans as people (Cody himself) who sprang from nature (the horse) to master technology (the repeating rifle). Throughout the performances, wilderness—animals and Indians—continually fell away before the advance of the American centaur, his settlements, and his technological prowess.

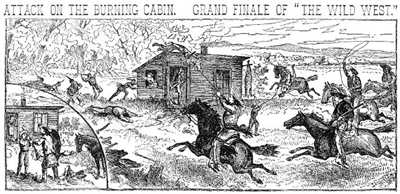

The story of technology and progress mediated by the ancient centaur energized one of the most durable of show scenes, the “Attack on the Deadwood Coach.” The Indian pursuit of the coach, and its rescue by Buffalo Bill and his cowboys, proved as durable as the Pony Express reenactment, and arguably the most thrilling, “never equalled by an act in hippodrome or theater,” in the words of an early reviewer. 55 In this scene, Indian centaurs pursued not just a stagecoach, but an Abbot and Downing Concord coach, a powerful icon of American artisanship. 56

As early as 1874, a correspondent remarked that “in the far West” the stagecoach “may be called the advance-guard of civilization,” but in most of the eastern states the railroad had already made it “a thing of the past.”57 Just as savagery vanished before the wheels of the stagecoach, so those wheels themselves gave way to machine-powered axles. East and West, anticipation of the coaches’ final passage became widespread by the early 1880s, symbolic of the passing away of the frontier, of master craftsmanship before mechanization (the Concord coach was so meticulously handcrafted that only three thousand of them were ever made), and of horse-drawn conveyance by steam locomotive and electric trolley, the revolutionary technology which, by 1896, was carrying passengers in ninety-three towns where Buffalo Bill’s Wild West appeared.58

Cody’s show publicists claimed that the coach had begun its career in 1863, journeying from New Hampshire to California by ship, seeing service in California, Oregon, and Utah, before becoming the “original” Deadwood coach, plying the route between the railroad depot at Cheyenne, Wyoming, and the gold-mining town of Deadwood, in Dakota Territory, in 1876. On this final segment of its twenty-five-year odyssey, wrote the publicists, it passed through “Buffalo Gap, Lame Johnny Creek, Red Canyon, and Squaw Gap, all of which were made famous by scenes of slaughter and the deviltry of the banditti.” Ultimately, it was “fitted up as a treasure coach,” carrying gold bullion from the mines and enduring spectacular robbery attempts, including the notorious Cold Spring holdup and another in which Martha “Calamity Jane” Cannary drove it to safety. Allegedly, Buffalo Bill had ridden in this very stagecoach, with Yellow Hair’s scalp and several others in hand, when he returned from his scouting duties in 1876. “When afterwards he learned that it had been attacked and abandoned and was lying neglected on the plains, he organized a party, and starting on the trail, rescued and brought the vehicle into camp.”59 Indians who attacked it in the arena were said to be “the near relations of the Indians” who attacked it on the Plains.60

Cody anticipated the consignment of all the West’s stagecoaches to history (stagecoaches would not cease the Deadwood run until 1890), then collapsed them and the biographies of show principals all into one coach. In tracing the route of the Deadwood stage through dark places full of evil— Lame Johnny Creek, Squaw Gap—the scene evoked the mythic progress of America through benighted savagery to civilization. At the same time, the symbol of the “vanishing” coach suggested that the era of frontier conquest itself was closing.

Of course, even beyond Cody’s fictionalized biography, the fakery of show programs was considerable, and nowhere more so than in the story of this stagecoach. Cody had not ridden out to save the coach from abandonment, but rather had ordered the vehicle from Luke Voorhees, manager of the Cheyenne and Black Hills Stage line, specifically for the show.61 He did not leave the Plains via this coach, or any other, the summer he killed Yellow Hair. Instead, he took a steamer to Bismarck and a train to Rochester. 62 This coach had no steel armor, was never a treasure coach, and had not been the target of the Cold Springs holdup.63

But through its convergence of historical events and mythic symbolism, the Deadwood stage became an object of near-spiritual veneration for the audience, a select few of whom passed through its doors during each performance. Stagecoach rides for audience members became a premier attraction of the Wild West show in every one of its future years. Pap Clothier’s more amenable successors included countless journalists, local councilmen, and, in 1887, the Prince of Wales and other European nobles, aristocrats, and celebrities who lined up to ride in the vehicle at Earl’s Court, London. In 1890, one of them, Lord Ronald Sutherland Gower, was astonished to come upon Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show in Italy. “I made again the circuit of the ring in the Deadwood coach.” Although he “had so often been inside” the vehicle at Earl’s Court, he had not dreamed “that I should repeat the drive under the shadow of Vesuvius.”64

By entering the coach, audience members became protagonists in the show’s historical narrative, and heirs to its myth. In its confines, they reenacted America’s passage through savage darkness and emerged victorious, like the Americans who had civilized the frontier. And as Americans watched European royals, urban elites, and elected leaders climb eagerly into the coach, they saw their history and a favorite show validated as high culture.

Thus, the Wild West show scene was simultaneously nostalgic, for a racial frontier that was passing, and forward-looking, with the wheels conveying the spectators-turned-passengers away from the primitive past and toward the technological future of wheels and guns that echoed from its driver’s seat. It was both a symbol of progress, looking forward to the passenger trains and the mechanical future that awaited the audience, America, and the world, and an anachronism, a handcrafted marvel in an age of mass production, a historical artifact conveying the lived experience of the frontier for the amusement of the modern city.

DERIVING CULTURAL MESSAGES like these from show scenes helps explain why the Wild West show became such a powerful factory of images and mythology, but it also makes it too easy to overlook Cody’s fundamental audacity, his reach for mythic trajectory in a show based substantially on circus entertainments, which remained far from respectable in middle-class parlors. The circus was “the devil’s playhouse,” wallowing in fraud, graft, and freaks who violated boundaries of all kinds. In their long quest for middle-class acceptance, circus impresarios often used biblical tropes to sell their attractions as moral education. One 1835 showman even staged “A Grand Moral Representation of the Deluge with Appropriate Sacred Music.”65 P. T. Barnum, the sage of Bridgeport whose avoidance of outright fraud earned him a reputation as a “moral” entertainer, made a systematic effort to equate his circus with biblical spectacle. He billed his hippopotamus as the “Behemoth of Holy Writ, spoken of by the Book of Job.” His African warthog became “the Prodigal’s swine,” and his camel “the ship of the desert.” Pastors and reverends trooped to his show for the free passes he distributed to the clergy. The efforts paid off. “The Greatest Show on Earth” was a rollicking success.66

By 1882, Cody had watched Barnum play his hand at the circus game for a decade. No doubt drawn by the comparative softness of press reviews, and by the large and heterogeneous audience, he followed the New Englander’s example. Cody and his partners imitated Barnum’s manner of loading trains. Like Barnum, Cody hired private detectives to patrol the grounds and travel with the show, running off known con men.67

But Cody went Barnum one better, creating a circus that was a distinctively American spectacle. Where clowns and elephants defined the circus, Cody had none. Where the circus was synonymous with the big top, Cody’s Wild West show had an open arena. In later years, he commissioned canvas awnings for the grandstands, but the performance space remained uncovered. The ostensible rationale for the lack of a roof was that shooting acts would quickly destroy a tent. But the view of the sky over the arena also created a symbolic connection to the wide frontier of memory and to nature, which publicists cannily exploited. Rain or shine, Wild Westerners worked beneath an open sky.68

Cody’s masterstroke was to avoid overt religious references in favor of a secular frontier myth with himself—or an artfully constructed version of himself—at the center. Barnum and other impresarios could grasp at the sacred. But overt religiosity was on the decline in the late nineteenth century, as religion permeated secular life and lost much of its power as a separate realm of authority.69 Besides, even for the most devout Christians, the Bible was an Old World text, with no material connection to the New World (a matter which evinced no little spiritual anxiety in America). Even if audiences could have participated in it, the Pentateuch and the Gospels were not easily dramatized by clowns, high-wire walkers, and bearded ladies. For many, Barnum’s piety smacked of a cynical ploy.

Cody’s show forsook conventional religion for nondenominational faith in progress—“ ‘Buffalo Bill’s Wild West’ is not a show in the theatric sense of the term, but an exposition of the progress of civilization.” 70 The effect was to give the circus a makeover so compelling and comprehensive as to make it unrecognizable.71 In its glory years, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West would generate gigantic poster art, including some of the largest show posters ever created. In 1898, one poster depicted the show’s main acts, including the “Attack on the Settler’s Cabin” and the “Charge up San Juan Hill.” It consisted of 108 sheets of poster paper, running 9 feet high and 91 feet long. A few circus competitors produced even bigger advertisements, and Ringling Brothers commissioned a poster more than twice as large. But the Ringlings’ depiction of separate attractions told no story. Impressive as it was, it looked like a big collection of smaller posters. 72

The effect of the advertising was analogous to that of the entertainments. Cody’s attractions included many that could be found in the circus: Indians and cowboys and Texas steers were featured in Barnum’s “Congress of Monarchs” as early as 1874. Not long after 1894, a sideshow of circus freaks was attached to the Wild West show. But in popular memory, even the most discordant Wild West acts could be subsumed into, or obscured by, the narrative arc of progress and frontier development. In contrast, the circuses of Ringling Brothers, Barnum and Bailey, and others remained a pastiche of the weird and the fabulous.

Presenting a national origin myth (one that conveniently elided the origins of slavery and the Civil War of recent memory) and allowing the audience limited participation in it, the Wild West show succeeded in convincing many that it was not a circus at all. Commentators and promoters intuitively grasped the distinctions. “There is as wide a gulf between the ‘Wild West’ and the Circus as there is between a historic poem and the advertisement of quack medicine,” wrote Steele Mackaye.73 The distinction made sense to the public. “ ‘Isn’t this better than the circus, now?’ was the delighted expression heard on every hand,” recounted an 1885 reviewer. So with the critics, who raved. They extolled. They waxed. But their very reluctance to describe the vivid presentation of frontier mythology as a circus in fact proved how successful Cody was at naturalizing the circus on American soil, turning it from a European import to a domestic entertainment. 74

From its opening night in Omaha, Cody and Carver’s Wild West moved on to Council Bluffs, Iowa; Springfield, Massachusetts; then on to Boston; Newport, Rhode Island; and Brighton Beach, New York, before closing out the season at Chicago. Throughout, the success of Cody’s new concoction of frontier, circus, and artful deception could be seen in reviewers’ frequent comparison to the greatest showman of all. “The papers say I am the coming Barnum,” wrote Cody to his sister.75 The Hartford Courant went further, proclaiming that Buffalo Bill had, “in this exhibition, out-Barnumed Barnum.”76

And yet, for all its successes, the Wild West show was a volatile combination of personalities and performance whose future was by no means secure. Carver, the self-styled “Evil Spirit of the Plains,” could be a fine marksman, but he was a third-rate performer. His shooting was uneven, his temper bad. After missing a series of targets one afternoon, he broke his rifle across his horse’s ears and struck an assistant. 77 Such open demonstrations of violence and cruelty were never going to be acceptable in any public entertainment, let alone the family attraction that Cody was trying to build.

On top of the threat of violence, Cody, Carver, and their cowboys drank hard all summer. Many performed badly or missed shows altogether. Later accounts claimed that an entire car of the show train was reserved for liquor. “It was an eternal gamble, as to whether the show would exist from one day to the next, not because of a lack of money but simply through the absence of human endurance necessary to stay awake twenty hours out of twenty-four, that the birth of a new amusement enterprise might be properly celebrated.” 78

What accounts for the management failures of Cody, a stage veteran who over the course of a decade in show business had mastered theatrical presentation and the demands of running his own stage company? Although he admitted to heavy drinking at times, he could be tediously pious on the subject of alcohol and performance. “In this business a man must be perfectly reliable and sober,” he lectured a wayward associate in 1879. 79 Why did he fail to follow his own advice at the outset of his new venture?

Partly, his missteps in the summer of 1883 reflected his limitations as a manager. He always had been more performer than manager, but the distinction between these talents became more visible as the size of his cast grew. Where he had directed and organized groups of up to two dozen stage players in the 1870s, now he was responsible for dozens of people, props, animals, and all of their transportation arrangements.

In facing this daunting task, he cannot have been helped by the prospective unraveling of his family. In 1882, he filed suit against a cousin for appropriating and selling a Cody family property that had belonged to his grandfather, the father of Isaac Cody. Since the parcel was in downtown Cleveland, it was worth a great deal of money, and for a time Cody and his sisters anticipated a windfall of fifteen million dollars. They endured legal setbacks throughout 1883, finally losing the case—and all the money William Cody had invested in it—in 1884.80

As his new show wobbled and his lawsuit waned, William Cody’s marriage spiraled downward. Louisa Cody resented his show career almost from the beginning. According to William Cody’s later testimony, she objected to actresses and the mores of the stage. He claimed that she witnessed him kissing his troupe’s actresses goodbye at the end of a season, and her subsequent jealousy throughout his stage career kept him “very much riled up . . . In fact it was a kind of a cat and dog’s life all along the whole trail.”81

The marital tensions, and the death of little Kit Carson Cody in 1876, may have contributed to her decision, in 1878, to move back to North Platte, away from his stage circuits, which took him through Rochester. He gave her $3,500 to move there, and sent money to support her thereafter. 82 In 1882, as he prepared for his new show of western pioneering, he also publicly reinscribed the show’s myth of advancing civilization back into his own life. Out in Nebraska, he built up his North Platte ranch, “Scout’s Rest,” for public admiration as much as private enjoyment. He expanded his holdings to four thousand acres. The estate supported hundreds of cattle and horses, and an elegant Victorian home, with irrigation ditches, tree plantings, and alfalfa fields. The Cody home in town had been a local tourist attraction before. Now, at the newly expanded holding by the tracks of the Union Pacific railroad, Cody ordered “SCOUT’S REST” painted across the roof of his barn in letters large enough that railroad passengers could read it and recognize the home of the famous Buffalo Bill. The beautiful house and verdant fields proved his powers as domesticator of the savage frontier. 83 People who sat in his show audience might find themselves on the train, there witnessing the “real-life” frontier progress of the scout-turned-rancher-and-family-man as they crossed the Nebraska prairie.

In truth, Scout’s Rest was less evidence of Cody’s home life than it was artful deception. Louisa refused to live there, preferring the family home in the center of town. Even though another daughter, Irma, was born to the couple early in 1883, their mutual suspicions increased. Cody raised money for his new show and his ranch by mortgaging properties, and he was furious when Louisa refused to sign mortgage papers for the home in North Platte. He demanded the money he had sent her, and was astonished to learn she had invested in other properties, which she put in her own name. “Well, I have got out my petition for a divorce with that woman,” he told his sister Julia in September of 1883, in the middle of his first Wild West show tour. “She has tried to ruin me financially this summer,” he went on. “I could tell you lots of funny things how she has tried to put up the horse ranch and buy more property & get the deeds in her name.”84

The divorce was halted by tragedy. In October, daughter Orra suddenly died. Cody left the show and accompanied Louisa, Arta, and Irma to Rochester, where they buried Orra next to her brother, Kit. “If it was not for the hope of heaven and again meeting there,” wrote Louisa, “my affliction would be more than I could bear.”85 Her husband dropped his suit for divorce.

Meanwhile, between the imminent violence, the extravagant debauchery, and the seething jealousy of its principals, the Wild West show threatened to come apart. The combativeness of its stars could only weaken an entertainment based so heavily on a presentation of men from the “half-civilized” West. Popular culture had a long tradition of venerating noble savages, and in this respect there was a script for presenting Indians in ways that could appeal to audiences. But by no means were cowboys universally regarded as heroic. With wide newspaper coverage of fights between farmers and cattle ranches in Kansas, and fierce range wars across much of the Far West, the public knew “cow-boys” as rough men who seldom distinguished between herding and rustling.

Such characteristics, it seemed, were only fitting for a group that drew its members from so many races. Most cowboy gear and methods originated among Mexican herders, and what became known as “cowboy culture” emerged from a vigorous interracial exchange of droving skills, terminology, and equipment on the southern Plains. The post–Civil War cattle industry employed many black, Mexican, Mexican American, and mixed-race cowboys alongside the white and tenuously white, particularly the Irish. In 1874, Joseph McCoy, the founder of Abilene, published the first history of the cattle trade, in which he denounced cowboys for their “shiftlessness” and “lack of energy.” He held Mexican cowboys to be cruel, mean, and murderous. But even white cowboys were prime examples of frontier degeneracy, plagued by laziness and an unwillingness to leave the open spaces or even feed themselves properly (McCoy thought the absence of vegetables from their diet problematic). “No wonder the cowboy gets sallow and unhealthy, and deteriorates in manhood until often he becomes capable of any contemptible thing; no wonder he should become half civilized only, and take to whiskey with a love excelled scarcely by the barbarous Indian.” Prone to “crazy freaks, and freaks more villainous than crazy,” these “semi-civilized” brutes rendered it “not safe to be on the streets, or for that matter within a house, for the drunk cowboy would as soon shoot into a house as at anything else.”86

Not surprisingly, the term “cow-boy” was often one of reproach, signifying someone who belonged to a lawless, itinerant, working class that, with its sensual appetites, obvious villainy, and continual threats of violence against civil order and the settler’s home, too much resembled the laboring mobs of the East. In 1883, as if anticipating the great railroad strike that would grip Texas and much of the Southwest a few years later, cowboys in West Texas went on strike in the hopes of securing wages of $50 per month. This and similar efforts later in the decade all failed. But to the managerial classes, the cowboys’ very act of striking seemed to justify the darker warnings about them.87

The Wild West show made cowboys into symbols of whiteness only through a balancing act, combating their border image on the one hand and portraying them as aggressively physical and autonomous on the other. Programs distinguished Wild West show cowboys, “genuine cattle-herders of the reputable trade” from “the cow-boys’ greatest foe, the thieving criminal ‘rustler.’ ” At the same time, publicity separated “American cowboys” from “Mexican and mixed race” vaqueros—and left black cowboys out of the picture entirely. Earlier cowboy performers had begun the process of whitening to better market themselves as middle-class attractions, and Wild West show publicists made use of these efforts, notably in an 1877 article by Cody’s erstwhile stage partner, Texas Jack Omohundro. The educated scion of a wealthy Virginia planter, Omohundro had been a Texas cowboy in the 1860s, and later a scout with Cody at Fort McPherson. As he broke away from Cody’s stage combination in the mid-1870s, he shored up his public persona by burnishing the cowboy image in a series of articles he penned for the periodical Spirit of the Times.

Omohundro died in 1880, but with a show full of cowboys to promote, Cody’s publicist, John Burke, republished Omohundro’s cowboy defense in his Wild West show programs. There audiences could read the lament of Cody’s deceased friend about how “sneeringly referred to” and “little understood” cowboys were. Omohundro claimed that cowboys were “recruited largely from Eastern young men,” including “many ‘to the manner born.’ ” Thus the mongrel, violent, degenerate range riders of many accounts became, in Omohundro’s hands, adventurous, entrepreneurial, white youths who succeeded through patience, persistence, and expert horsemanship. Cowboy experience cultivated the “noblest qualities” of the “plainsman and the scout. What a school it has been for the latter!” As white men infused with rugged nature, these protoscouts were on the way to being like Buffalo Bill himself. And like him, they would soon disappear before “modern improvements” encroaching upon the “ranch itself and the cattle trade” that employed them.88 They were the embodiment of American manhood: cultured, vigorous, natural—and vanishing.

But for all Omohundro’s attempts to elevate the social stature of cowboys, their image as frontier degenerates endured. In 1883, the American public was fully saturated with the recent, real-life bloodshed of western range wars. The Tombstone troubles launched that southwestern town’s “cowboy faction” and their opponents, the Earp brothers, to national notoriety, and New Mexico’s Lincoln County War saw the declaration of martial law in southern New Mexico in 1878, and the rise, demise, and apotheosis of William “Billy the Kid” Bonney by 1881. 89 The Wild West show would have to improve the cowboy’s public image if it was to draw respectable audiences. Unless the chaotic energies of the Wild West cast were contained and directed, the show’s short, disastrous career would become a spectacle of frontier savagery triumphant, in which drinking and carousing (followed by bankruptcy) would make it a monument only to the failures of America’s most famous living frontiersman.

HOMEWARD BOUND: SALSBURY, OAKLEY, AND THE RESPECTABLE WILD WEST

Unable to resolve his many differences with his new partner, Cody was barely breaking even by the end of the summer.90 The show’s tempestuous, overly masculine cast attracted a crowd that resembled it. In late October 1883, the Chicago Tribune reported that five thousand people turned out to see the Wild West show, and dropped hints aplenty that the audience was not quite respectable. Although all entertainers hoped to attract as big an audience as possible, “decent” people were likely to avoid a crowd that was racially mixed. And so it was at Buffalo Bill’s show, where “the crowd was a mixed one, and the newsboys and bootblacks formed a large and important element of it.” In the Wild West camp, “ferocious-looking prairie-terrors” lassoed “the ubiquitous gamin.”91 The reviewer, in fact, seemed as preoccupied with the show’s youthful, impoverished enthusiasts as with the entertainers.

They had seen the parade of the buckskin-clad heroes and painted savages, and their thoughts turned toward the interior of the yellow-covered novels and five-cent libraries through which they had waded in company with daring scouts. Their energy in selling papers and giving shines was redoubled, and one would have thought to see them all over the track that there was not a gamin in the city.92

The reference to dime novels was a coded warning, much like the hidden clues to the disreputable crowd at Cody’s theatrical performances. Newspapers and other organs of culture regularly condemned dime novels as lurid, violent inducements to crime. In the same column as the above review, the Chicago Tribune reported on two teenage thugs who beat and robbed two men on a streetcar, under the headline “The Dime Novel. Two of Its Heroes on Trial for Highway Robbery.” 93 The reviewer’s description of a destitute army of youthful crime enthusiasts swarming to a show of prairie bad men can hardly have been reassuring for prospective middle-class customers.

Nate Salsbury saw the show in Chicago and predicted it would fail. Within days, Cody gave him the opportunity to prevent it. According to Salsbury, “Cody came to see me, and said that if I did not take hold of the show he was going to quit the whole thing. He said he was through with Carver, and that he would not go through such another summer for a hundred thousand dollars.” 94

In Salsbury, Cody sought out one of the most experienced and successful theatrical managers in the country. Born in 1845, Nathan Salsbury was an orphan by the time he was fifteen, when he joined the Union army. He fought at Chickamauga and Nashville, among other battles, and was eventually taken prisoner. After the war, he entered the stage, playing with various minstrel companies before forming his own Salsbury’s Troubadors in 1874.

Beginning with this small-scale variety show of songs, dances, and comedy routines, Salsbury became a primary developer of what became known as musical comedy. Where variety performers presented unrelated routines of singing, dancing, and comedy on the same stage, Salsbury placed them together in a unified narrative, a simple play about a picnic, entitled The Brook. In the course of an afternoon outing, a cast of characters ventured out on a picnic, where each character performed her or his routines, then returned home again. As one theater historian has observed, this was “hardly an earth-shaking plot,” but it nonetheless “revealed the possibility of stringing an entire evening of variety upon a thread of narrative continuity instead of presenting heterogenous acts.”95 It was extremely popular. For twelve years, Salsbury’s Troubadors toured the United States, Australia, and Great Britain, to considerable fame and a not inconsequential fortune. They earned something approaching middle-class respectability. The same newspaper that warned readers about the Wild West show also condemned the clumsy play that Salsbury’s Troubadors performed in Chicago (My Chum, by Fred Ward), but the reviewer’s complaint was that the drama was beneath the talents of these “genial people” whose successes with The Brook and other comedies had fulfilled their mission of “amusing the public.”96

Many modern readers, understandably ignorant of how Cody was inspired by his experiences on the Plains, have accepted Nate Salsbury’s self-aggrandizing claim to have created all of the major attractions of the Wild West show. Salsbury’s overstatement is so crude it barely requires refuting. Most of the show’s enduring scenes, including the “Pony Express” and “Deadwood Stagecoach Attack,” appeared in the first season, as did various versions of the Buffalo Hunt. So, too, did demonstrations of cowboy skill, and Cody’s own display of horseback shooting, not to mention the exhibition of Indian dances and combat between Indians and cowboys: all were part of the 1883 season, before Salsbury joined. Cody had been developing an entertainment based on Indians and real frontiersmen—especially himself—for over a decade. Before Salsbury came along, most of the elements for a successful show were on hand.

Still, Salsbury’s contribution was significant. His earlier success flowed from his ability to make narrative drama from distinct entertainments. In his hands, skits of dancing, singing, and juggling became related “acts” of a larger story, such as The Brook. In contrast, Cody’s experience was in melodrama, a genre which came with one-size-fits-all narrative about restoration of the true woman to home and domestic bliss. His new arena presentation being in part an effort to escape the constraints of melodrama for frontier history, but it left him flailing for a new narrative structure. The Wild West was already exciting and dramatic, but its lack of clear direction was apparent in its narrative confusion, notably the absence of a suitable ending. As spectacular as the buffalo hunt was, it failed to resolve the combative drama of the earlier white-versus-Indian scenes, and therefore proved anticlimactic. Cody’s efforts to rectify the situation resulted in some bloody spectacles indeed. Perhaps in an artistic expression of what it felt like to run the Wild West show during its first season, the final act of the Chicago show program for 1883 was “a grand realistic battle scene depicting the capture, torture, and death of a Scout by the savages.” This was followed by a vengeful conclusion, which veered close to the degenerative Indian hating Cody had scrupulously avoided: “The revenge, recapture of the dead body, and victory of the Cowboys and Government Scouts.”97

Cody and Carver had an acrimonious falling-out at the end of the 1883 season, and in 1885 Cody finally won a subsequent lawsuit over who was entitled to use the name “Wild West.” Meanwhile, Salsbury had joined the Wild West show, catching up with the encampment in the spring of 1884 at St. Louis. He later recalled that he found Cody leaning against a fence in plug hat, “boiling drunk,” surrounded by “a lot of harpies called ‘Old Timers’ who were getting as drunk as he at his expense.” According to Salsbury, Cody’s spree “lasted for about four weeks,” when he became so ill “he was knocked out and had to go to bed.”98

Salsbury’s first demand was sobriety. Cody agreed. “I solemnly promise you that after this you will never see me under the influence of liquor. . . . [T]his drinking surely ends today and your pard will be himself. [A]nd be on deck all the time.” The partners demanded temperance among their employees, too, and devoted much of their publicity to the “orderliness” and sobriety of the camp.99 Although he occasionally strayed, in future years Cody generally was sober during the show season.100

Salsbury next applied his sharp sense of drama to Cody’s alluring but incoherent assemblage. Although it is not clear when the Cowboy Band came on board, Salsbury’s career had been in musical theater, and it seems likely he exerted his influence in this respect. By 1885 the show had an orchestra consisting of several dozen professional musicians dressed as cowboys. Like the bands that accompanied circuses, the Cowboy Band provided musical pacing for show acts. Beginning each show with “The Star-Spangled Banner” as an overture (although the song would not become the national anthem until 1931), their music set the mood during each act and then provided bridges between them.101

Salsbury’s arrival also coincided with the addition of one new “tableau,” which would play a major role in the show’s success. Beginning in 1884, and continuing almost every year through 1907, the climactic scene of Cody’s show was the spectacle of a house in which a white family, sometimes a white woman and children, took refuge from mounted Indians who rode down on the building. The attackers were in turn driven off by the heroic Buffalo Bill and a cowboy entourage.102

The “Attack on the Settler’s Cabin” tapped into a set of profound cultural anxieties. For nineteenth-century audiences a home, particularly a rural “settler’s” home, was imbued with much symbolic meaning.103 The home itself presupposed the presence of a woman, particularly a wife. The home conveyed notions of womanhood, domesticity, and family. When the Indians rode down on the settler’s cabin at the end of the Wild West show, they were attacking more than a building with some white people in it. To many in the audience, the piece conveyed an attack on whiteness, on family, and on domesticity itself. With its new ending, the Wild West show adapted the melodramatic rescue of the home for arena performance, allowing the cowboys and their leader, the scout (a famous melodrama star, after all) to rescue the nation’s domestic unity from the threat of Indian captivity, and thereby bring the furious mobility of the show—the constant racing of its races—to a rest.

Middle-class people distinguished themselves from other classes partly by their emphasis on private, quiet home life, on what the historian Mary Ryan has called “entrenched domesticity.”104 By putting home salvation and family defense at the center of the show’s climax, Cody and Salsbury made their performance resonate with widespread middle-class concerns, and began the work of coaxing middle-class urbanites away from their homes long enough to see the show.