Standing Bear

HE WAS BORN a Minneconju Sioux, in 1859, by the cold, clear waters of the Tongue River, where his people sheltered from the winter blasts. He came of age hunting buffalo, fighting the Crows, and the Americans. He was a veteran of the battle of the Little Big Horn, where he fought when he was seventeen. As he later put it, he feared “the white men would just simply wipe us out and there would be no Indian nation.”1

He was called Standing Bear. The name was not uncommon among the Lakota, and other men who shared it found their way to the Wild West show over the decades. (Luther Standing Bear, a Brule Sioux who joined the show in 1903 and who went on to become a movie actor, an author, and an activist, was no relation to this Standing Bear.)

In 1887, Standing Bear joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West for its debut European season. He was with the show again in 1889 and 1890, during the Paris exposition and the tour of the Continent. In Vienna, he was injured in the show arena. Neither documents nor family tradition indicate what the injury was, but it required hospitalization. With several other Indians in the 1890 season, Standing Bear was left behind to recover. When the show departed Europe, Cody and Salsbury left a ticket for him at the American consulate, and instructions with the hospital on how to retrieve the ticket. 2

Like many other Austrians, the nurse who tended Standing Bear, Louise Rieneck, was fascinated with Indians. She had seen the Wild West show in Vienna. As a Lutheran in Catholic Austria, she was already a social outsider. She was something of a linguist as well. Other than German, she read Latin and spoke French and English. From her patient, she began to learn Lakota.

Standing Bear was hardly alone in becoming the focus of a European woman’s attention. He was a cousin of Black Elk, who had an English girl-friend, and of Red Shirt, who was admired by many women in Europe. Standing Bear was in the Paris camp in 1889 the day the prodigal Black Elk caught up with Cody’s show, and probably sat with him that night at the celebratory dinner. Many years later, Black Elk recalled the English woman he had just left. “I told my girl that I would go first and she would come afterward.” He was unable to keep that promise. 3

Standing Bear, c. 1892. Courtesy Arthur Amiotte.

Family tradition suggests Standing Bear had a wife at home. If so, they may have been in contact while he was in Europe. Many show Indians dictated letters to European and American friends, and sent them through the Indian agent on the reservation.4

Sometime in early 1891, while he was convalescing in Austria, Standing Bear received word of the calamity at Wounded Knee Creek. His wife was dead. Not long after, he realized he could not leave Louise. Early in 1891, Standing Bear and Louise Rieneck were married. Then the couple was bound for the United States. On February 16, their ship, the Standia, docked in New York. Standing Bear arrived with Louise, her parents, Ernst and Hedwig Rieneck, and two young girls, Maria, age two, and Martha, age three, whose relationship to Louise has never been established. The entire family moved to Pine Ridge, but after a few years, Louise’s parents missed certain amenities (among them, says family tradition, the beer and wine which were illegal on the reservation). With Martha and Maria, they moved to Chicago, where they prospered in dry goods.5

Standing Bear never joined the Wild West show again. His wife, who was soon known as Across-the-Eastern-Water-Woman, gave him much comfort and a reason not to stray too far. From the time he and Louise moved onto the reservation, they formed a powerful partnership that joined their shared energy and innovative spirit. His extensive female kin taught Louise about making a Lakota household. She brought them her knowledge of European medicine, horticulture, and animal husbandry.

The couple provided services others could not. Poverty and disease took a heavy toll on neighbors and family. Traditionally, the Sioux placed their dead on scaffolds. Now, officials dictated that all bodies must be interred in the earth, in caskets. The caskets were simple wooden boxes, but they were expensive, and they were only available at the government commissary at Pine Ridge, a full day away by wagon. The time it took to travel there was almost as great an expense as the money.6

Louise knew basic carpentry, which she taught Standing Bear after they bought some hammers, saws, and a plane. She ordered velvet, linen, and silk from her parents’ store in Chicago. Before long, neighbors drove from miles away for the simple, lined caskets, which they paid for in cash or in kind at Standing Bear’s home. Louise also made silk and paper flowers, and taught the skill to local Lakota women.

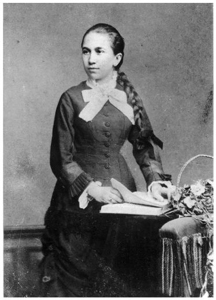

Louise Rieneck, age sixteen, in Dresden, Germany. CourtesyArthur Amiotte.

After 1900, Standing Bear and Louise moved to a new location on Whitehorse Creek, west of Manderson, where many of his extended family (including Black Elk) were settling. There, he plowed verdant meadows for a large garden. They continued to make caskets, and Louise’s knowledge of European medicine proved a boon, too. She ordered basic medicinal supplies through her parents in Chicago, and for decades, she was something of an unofficial country doctor who delivered babies, tended the ill, and dispensed medicines and advice.

Three daughters, Hattie, Lillian, and Christina, were born to Standing Bear and Louise. In the reservation era, Pine Ridge society was increasingly divided between “mixed-bloods” and “full-bloods.” Mixed-bloods generally affected western clothing, were bilingual in Lakota and English, and had many contacts among white businessmen and more access to cash. Full-bloods spoke mostly Lakota, and their associations were more restricted to Lakota-speakers. They were generally poorer than mixed-bloods. Although the labels were racial, in reality such identities had as much to do with cultural choices as with ancestry. There were many children of mixed unions who did not identify with mixed-blood culture, and many full-bloods who assumed certain attributes of mixed-blood identity, too.

For their part, Hattie, Lillian and Christina moved gracefully on the mixed-blood/full-blood divide, attending the mixed-bloods’ “white man dances” in beautiful European-style dresses they made with their mother on her sewing machine, and their father’s traditional Lakota dances and ceremonies in Lakota-style dresses embroidered with beads and elk teeth. In fact, mother and daughters turned the cabin into a veritable factory of clothing: western- and Lakota-style dresses, as well as shirts, pants, and quilts, rolled off their sewing tables. At the same time, they continued to make moccasins of hand-tanned deer and cow hide, using traditional awls. 7

So the family prospered. Seasonally, Standing Bear and his relatives drove their cattle between pastures at Whitehorse Creek and the high meadows of Red Shirt Table, where their cousins, the families of Red Shirt and High Eagle, helped tend their herds. Back at Whitehorse Creek, they cut hay for the winter, and before the fall frost, they slaughtered cattle and dried beef for winter storage and for gifts to neighboring families that were an obligation of their comparative wealth. The women of Standing Bear’s family taught Louise to gather and preserve chokecherries, buffalo berries, wild currants, and plums; she taught them to make savory German preserves, like sauerkraut, and pickles in brine. With plentiful cattle, and with the men bringing in deer occasionally, there was always a pile of hides that needed tanning, or gardening to do. Relatives and friends in need could drop by, offer their work, and take home food, clothing, and moccasins. Standing Bear’s influence grew. He became a chief of his local community, renowned for his generosity.

Although he resisted allotment, like many Lakotas, Standing Bear eventually reconciled himself to it. By 1911, he and Louise had a large, hand-hewn log cabin, painted white, with a shingled, pitched roof, wooden floors, and frame windows. Two years later, visiting officials reported they also had a cabin and a barn and 640 acres of land, with 80 acres under plow. They owned one hundred cattle and thirty horses. At a time when the average U.S. worker made just $621 per year, they had $1,000 in savings.8

In Wild West show drama, Standing Bear and other Indians were powerful symbols of the theory of history embedded in the concept of race. They embodied pure, unalloyed primitivism and savagery. Through conflict with another pure race—of white, civilized people—they were subdued. Buffalo Bill’s cowboys guaranteed that the Indian race would be contained within its original borders—Indian bodies—by enforcing a perimeter around the body of the vulnerable white woman in the settler’s cabin, away from which they drove the Indians.

But through performing in the same Wild West show that expressed white supremacy, Standing Bear and a few other Lakota men found wives across the racial divide at the turn of the century. For the Lakotas, the only thing that made marrying white women a strange concept was white hostility. Race was less a factor in Lakota identity than residence and behavior. By living among Lakota and acting Lakota, one became Lakota. In some ways, Standing Bear’s marriage to Louise was traditional. Lakota culture allowed for marriage of alien women through capture in war or through friendly alliance. Any Cheyenne, Pawnee, or American woman who married a Lakota man, learned to speak Lakota, and made a home with him among Lakota, became Lakota.9 Perhaps because intermarriage was a traditional means of creating alliances with powerful families and peoples, Sioux men who won the hands of white women were often ambitious and forward-looking. In 1890, while Standing Bear was convalescing in Vienna, a Santee Sioux man named Winner—who had taken the name Charles Eastman— became the first Indian to receive a medical degree, from Boston University. In the same year that Standing Bear married Louise Rieneck, Dr. Charles Eastman married Elaine Goodale in New York. 10

For all its exclusionary racial teachings, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show was a vehicle for at least a few, and probably a great many, Indian men to meet and love white women, and in at least a few cases the lovers married. Although the vast majority of its cast did not have the experience of Standing Bear and Louise, for some, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, spectacle of race enmity, became a path to a future that reconciled blood and culture. The future lay in mixing peoples together.

Standing Bear and Louise (Across-the-Eastern-Water-Woman), at their cabin, with granddaughters Rose Two Bonnets and Lula Two Bonnets, c. 1915. Courtesy Arthur Amiotte.

This was Standing Bear’s strategy. He refused to learn English himself, but insisted that his children and grandchildren learn it. He refused baptism, too, until his daughters prevailed on him late in life. But at the same time, he and Louise grafted European and Indian business and craft techniques onto one another to make a new living, to carve out a new kind of story about the Lakotas and Europeans, which they would live. The contours of that story floated beneath the surface of frontier ideologies like Buffalo Bill’s. But still, they hearkened to a real frontier history of mixed blood, which, as we have seen, typified relations on the northern Plains for many people throughout the nineteenth century. Standing Bear and Louise simply dismissed all the stigma of “miscegenation” among Europeans and Americans, and embraced that venerable legacy of mixed marriage as the path to a bright future.

Standing Bear devoted himself to history and art. While his daughters were growing up, he spent most evenings, after his work was done, painting scenes of the Lakota past, especially of his own generation, in traditional style, on large pieces of white muslin. He consulted with neighbors, his age-mates, on details of the images, and the deeds and events they recorded. In 1930, the poet John Niehardt arrived on White Horse Creek, asking to interview Black Elk. Standing Bear joined the discussions. Two years later, when Niehardt published Black Elk Speaks, Standing Bear’s testimony appeared with Black Elk’s, and his illustrations appeared throughout the book. To this day, his art is among the most evocative, and coveted, of the period.

Louise and Standing Bear lived at White Horse Creek until 1933, when she died soon after being in a car accident. The reservation reeled from depression and drought. Standing Bear grew tired, depressed. He passed later that year.

Arthur Amiotte is one of Standing Bear’s great-grandsons, and like Standing Bear, he is an artist. Amiotte works from his studio in Custer, South Dakota, and his renowned collages explore his family history, mingling painted images of Indians—including Standing Bear—with early automobiles, frame houses, and photographs of Indians at church, on the road, and in Europe.

Much of Amiotte’s early inspiration came from stories he heard from his grandmother Christina, a daughter of Standing Bear and Louise who lived in the home her parents built until 1985, and continued their tradition of generosity all her days. As Amiotte grew up, she related stories of the many relatives who would travel to White Horse Creek, to pitch their tents outside the Standing Bear home in warm weather. There were people gardening, tanning hides, plowing, and butchering cattle, and children playing ball with inflated cow bladders. In the evenings, after they turned the lamps out, Standing Bear and Louise lay in their bed, with family and sometimes guests sleeping on the floor in bedrolls. In the darkness, they told stories. Some were ancient tales. Some told of Standing Bear and his age-mates, and their adventures in Europe. Sometimes, Standing Bear and Louise performed the dialogue of the characters in the stories, and their ability to mimic voices enthralled the children, and kept them in stitches. This tradition, too, continued after they were gone. Christina and her husband, Joseph Mesteth, a mixed-blood of Lakota and Mexican descent, told their stories to their children and grandchildren.

This was more than entertainment. In the darkness, the children drifted off, to sagas of hero-creators, warrior ancestors, and long, strange trips with Buffalo Bill all weaving the space between waking world and sleep, where the consciousness of a people resides.11