CHAPTER FIFTEEN

Buffalo Bill’s America

AFTER WOUNDED KNEE, Cody did not learn he would be allowed to hire Indians again until March of 1891. Salsbury sought out new contingents of racial primitives—other Others—who could replace Indians. By the time the show regrouped in Strasbourg, in the spring of 1891, Salsbury and Cody had incorporated twelve Cossacks and six Argentine gauchos, as well as two detachments of regular European cavalry—twenty Germans, and twenty English—to join twenty Mexican vaqueros, two dozen cowboys, six cowgirls, a hundred Sioux Indians, and a cowboy band of thirty-seven.1

The additions were the culmination of Salsbury’s earlier ideas for a show of world horsemen, paralleling developments in European circuses, which were employing Cossacks, Arabs, and other exotic trick riders and horsemen in Europe in the 1890s.2

This new Wild West show now toured parts of Western Europe. In Germany, Kaiser Wilhelm II was a fan. Annie Oakley recalled “at least forty officers of the Prussian Guard standing all about with notebooks” to record the show’s rapid deployment of railroad, horses, and ranks of men in arms. German military interest was echoed across the Atlantic, where the American army was studying circuses for similar reasons.3

After Germany came Belgium and the Netherlands, then a tour of the British provinces. Late in the fall, there was a reprise of The Drama of Civilization at the East End Exhibition Hall in Glasgow.4

Despite the size and military presence of the new Wild West show, Cody found himself ever more besieged behind the lines. Louisa insisted that the newly married Arta and her husband, Horton Boal, assume management of Scout’s Rest Ranch. Cody resisted, for it would mean evicting his sister Julia and her husband, Al Goodman. “I want you to live there just as long as you are contented there,” Cody wrote his brother-in-law. Louisa made life difficult for the Goodmans, and Cody lamented it. “I often feel sorry for her. She is a strange woman but don’t mind her—remember she is my wife—and let it go at that. If she gets cranky just laugh at it, she can’t help it.”5

But after a bitter squabble the Goodmans abandoned the fight and moved back to Kansas. Louisa, whose relations with Julia had always been cool, now had an ally at Scout’s Rest in her daughter Arta. Her victory was short-lived. Arta and Horton abandoned the job within three years. Al Goodman returned to manage the ranch again. But this time, mindful of Louisa’s hostility, Julia stayed away.6

In the spring of 1892, the Wild West show returned to Earl’s Court, London. There was another command performance at Windsor Castle for Queen Victoria, who was enamored of the Cossacks.7 The tour was a success, but the novelty of the Wild West had faded considerably since 1887. To repeat the great fanfare of their London debut five years before, Cody and the company had to wait till the following spring, when the newly christened “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World” opened outside the gates of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Extensive newspaper coverage of Cody’s European successes heightened popular interest in the show, which had not toured the United States since 1888. In Chicago the new format recharged the show’s authenticity and its frontier myth. Cody’s connection to Sitting Bull and the Ghost Dance troubles, and the continuing presence of Ghost Dancers like Kicking Bear and Short Bull, provided a red-hot connection to the Far West and the American frontier, which in turn facilitated a depiction of the new acts—Cossacks, gauchos, and European cavalrymen—as relics of ancient racial frontiers.

To a degree, the circus roots of the new racial segments suggested the continuing dance of the Wild West show with the big top. Railroad circuses proliferated in the 1890s, until over a hundred of the giant amusements toured the United States after 1900. As modern corporations that displayed exotic peoples for popular amusement, the Wild West show and its circus competitors constituted “a powerful cultural icon of a new, modern nation-state,” in the words of historian Janet Davis.8

But the Congress of Rough Riders also hints at how the show’s extended European sojourns had taught Cody and his publicists to speak of Eurasian and American frontiers in the same breath. When the Wild West cast visited the field of Waterloo in 1891, Cody told a journalist about the “striking resemblance” of this battlefield to the Little Big Horn. (Of course, the comparison allowed readers to make up their own minds about whether Custer was “the Napoleon or the Wellington of the conflict. He looked out for the arrival of Major Reno, who was destined either to be the Blucher or the Grouchy of the close of the fight.”)9

Back in Chicago, the opening at the world’s fair reflected the development of the show’s marketing strategy. By this time, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West practically orbited the world’s fairs and exhibitions which proliferated in the United States and Europe, from the New Orleans Cotton Exposition of 1885 to the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1889. As popular celebrations of progress which explored the meaning of national expansion and newfound prosperity, world’s fairs were ideal places for traveling entertainments to pitch their tents, especially a show of the “progress of civilization” like the Wild West show.10

The center of the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 was the White City, a group of huge, neoclassical buildings, constructed of wood and plaster on reclaimed marshland along Lake Michigan, symbolizing the glories of America and containing exhibit space for every state and many nations, too. The architectural heart of the fair was the Court of Honor, a grand plaza with a huge pond and a fountain in the middle. Soaring over the watery mirror of the pond was the Statue of the Republic, a sixty-five-foot-tall, gold-plated Lady Liberty. The statue, the gleaming white buildings, the arcing fountains could move visitors to tears with their “inexhaustible dream of beauty,” in the words of poet Edgar Lee Masters. They could also be subjects of ridicule: the statue was widely known as “Big Mary.”11

The Wild West show was not in the White City, but outside the fair proper, along the route to the entrance, on what became known as the Midway Plaisance. Fair organizers reserved this space for exhibits that were too commercial, or too similar to circus or carnival attractions, for inclusion in the edifying White City. But Cody’s success in this location was a finger in the eye of fair officials, who came to regret their decision to exclude him. Because of the joint attractions of the White City, the Wild West show, and the Midway, Cody and Salsbury sold well over three million tickets in 1893, making profits of over a million dollars. It is said that spectators sometimes mistook the Wild West show for the World’s Fair, and went home satisfied.12

In recent years, scholars have followed the crowds to Buffalo Bill’s 1893 season, taking imagined walks up the Midway for lessons in the rise of mass culture and Gilded Age notions of race, conquest, and progress. The kaleidoscopic attractions of the World’s Columbian Exposition in many ways reflected or amplified aspects of Wild West teachings. Exhibits and displays on the Midway were situated so that those featuring the most “primitive” peoples—South Sea islanders and mock Ethiopian villages—were farthest from the White City. As one approached the gates of the exhibition proper, one encountered ever whiter, more “advanced” peoples. The Wild West show was right outside the White City gates. The social evolution of the Midway and the world’s fair echoed the social evolution of Cody’s arena (while inside the fair, one hot July night, historian Frederick Jackson Turner expounded on the role of “free land” in stimulating social evolution along the American frontier). Tickets to the Wild West show announced it as the “Key to All,” as if its story of relentless progress organized the fair’s mysteries and unlocked the narrative which explained them all.13

But for modern readers who want to know how Gilded Age Americans thought about Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, the 1893 season is at best a slippery key to a hall of mirrors. The world’s fair, the Midway, and the Wild West show were infused with so much exhibitionism, outlandish display, performance, exotica, hoax, fraud, artful deception, and amusement as to turn an imaginary trip to Cody’s show into a fun-house tour. The swirling cultural disjunctures of the world’s fair left many observers disoriented even at the time. There were swimming races and boat races in the newly dredged lagoon in Lake Michigan, between Zulus and Turks. Visitors floated by in mock Venetian gondolas, poled by real gondoliers (imported from Venice) in ancient costume. Fair exhibits included a chocolate Venus de Milo, a giant horse and rider made of prunes, and, over in the Wisconsin Pavilion, a 22,000-pound cheese.14 In August, there was a Midway ball—one paper called it the “Ball of the Midway Freaks”—at which a white-clad, fez-wearing George Francis Train (said to have been the inspiration for Phileas Fogg, hero of Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days) led a procession of exotic women onto the dance floor at the fair’s natatorium. In short skirts made of tiny American flags, they waltzed and quadrilled with eminent Chicago gentlemen in black dress suits until four-thirty in the morning.15

The image of Cody’s show as a bastion of Americanism and originality in a world of effete culture was already traditional. In 1893, Chicago critics welcomed Buffalo Bill’s Wild West as a natural, American counterpart to all the mock Greek and Roman statues, bone-white neoclassicism, and flat-out weirdness of the White City. “There,” wrote Amy Leslie, pointing to the Wild West, “is the American Exposition.” At Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World, visitors could “find Americans, real Americans . . . if not in the audience in the performance.” 16

The bizarre distractions of the world’s fair context make it harder to deduce what visitors saw in the Wild West itself, and besides, the show’s whopping 3.8 million admissions were perhaps less significant than they seem. Unknown numbers of those millions were return customers. The show sold 2 million tickets during the 1886–87 appearances at Erastina and Madison Square Garden, when the number of return visitors (who had no Midway Ball, gondolas, or giant cheese to attract them) was probably much lower. 17 In the end, most Americans who saw the show saw it not in Chicago but much closer to home, and the constant cross-references between White City and Wild West in 1893 tell us more about the meaning of the world’s fair than they do about how most Americans understood the Wild West show in its most successful decade.

The Chicago season of 1893, where the Rough Rider spectacle unfolded amidst a global extravaganza, underlies the common historical argument that Cody’s new format infused America’s newfound overseas ambitions with frontier mythology and expressed public sentiment for empire. To be sure, Cody’s show did resonate with U.S. foreign affairs, in complex ways, as we shall see in the next chapter. But public commentary about the show suggests the Rough Rider drama engaged the public on more familiar ground: the challenges of urban living, industrialization, and immigration, all of which touched and shaped daily life for the millions who attended the show in 1893 and after.

In this regard a more revealing season than that of 1893 is the following year’s six-month stand in Brooklyn, which was in many ways the apogee of its long stands. The show’s open-air ambience was in keeping with the way most spectators saw it, whether it was appearing in Elkhart, Indiana, or Stockton, California. Moreover, the venue was an independent, fully industrialized city, allowing us to see how the nostalgic spectacle of the vanishing (or vanished) frontier appealed to the increasingly urban populace. The completion of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883 had initiated a furious expansion. By 1894, Brooklyn’s overall population approached 900,000, and was growing by 25,000 people per year. It was already half the size of New York, which was the nation’s largest city and the destination of most Brooklyn commuters who, six days a week, crossed the new bridge to work. Most of Brooklyn’s buildings were homes, but it was also America’s fourth-largest industrial metropolis. Half the sugar in the United States was refined there. The city’s giant grain elevators had four times the capacity of New York City’s, and its piers unloaded the cargo of four thousand ships a year.18

For our task, the city provides a better indication than a world’s fair of how the show was received. In contrast to the phantasmagoria of the World’s Fair, there were no competing attractions for the Wild West in 1894. Construction of Brooklyn’s legendary amusement parks at Coney Island would not begin for another year.19 The Wild West show’s Brooklyn summer was the culmination of over a decade of show appearances, and it was also the last of the show’s long stands in the United States. Beginning in 1895, a new partnership with James A. Bailey, of Barnum & Bailey, would put the show on the road for one- and two-night stands.20

Historians have often summarized the show’s new format—Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World—as merely an expanded version of the original entertainment. But it was more than that. Judging by the growth in clippings pasted into surviving scrapbooks, the appeal of the Congress of Rough Riders was deeper and broader than the original Wild West show. The crowds who came to see it were distinct from the crowds of the mid-1880s, and they saw it in different ways. Although nostalgia for the frontier was as great as ever, the show was now much more than a spectacle of a vanished world. In surprising ways, audiences drew lessons in the challenges of urban life, and their possible solutions, from this show of frontier drama.

One key to relevance for Cody’s Rough Riders in this urban setting was its gathering of frontier rhetoric and Indian war into a discussion that incorporated many of the immigrants and new Americans who constituted the modern city. As Matthew Frye Jacobson has observed, in the closing years of the nineteenth century, America was preoccupied in part with the necessary import of labor to produce the profusion of goods and services that defined the industrial economy.21 America’s encounter with the world was occurring not only overseas but also within American borders. Cities teemed with strange, sometimes mysterious, and often frightening immigrants and alien neighborhoods. The urban middle classes—white, English-speaking, and educated—felt ever more besieged. The Congress of Rough Riders, combining Eurasian and American riders, whirling with color and martial ardor, and arrayed in a grand historic narrative, provided a story and a means of understanding America’s place in a world that often seemed to be overrunning the United States.

In doing so, the Rough Rider additions layered new meanings onto Cody’s entertainment which few could have foreseen at the debut of the Wild West show a decade earlier. Part of the Rough Riders’ appeal was the way they allowed Americans to experiment with an older tradition of ethnic comparison. As we have seen, Americans compared their frontier horsemen, especially Indians and cowboys, to a host of legendary, exotic riding contingents, including Cossacks, Gypsies, and Turkmen. In the same breath, they compared them to riders in the circus, an amusement which after all was founded by Philip Astley, a cavalry officer from foreign shores, and which often featured exotic (or exotic-looking) trick riders. William Cody ventured a sort of comparison between Cossack riders and American cowboys in an interview with a Philadelphia journalist in 1888: “I don’t know anything about cossack riding, because I never saw any of it, but I will guarantee that our men can do anything that cossacks can do and more, too.”22

Allowing Americans to witness the real riders of legend, and to make their own decisions about which peoples produced the best horsemen, was no small thing. As we have seen, the lone horseman was a fading figure in the modern urban world, but his command of the animal reflected his control of nature and signified the strength or weakness of racial energies. As Frederic Remington observed about the show’s Rough Riders, “The great interest which attaches to the whole show is that it enables the audience to take sides on the question of which people ride best and have the best saddle. The whole thing is put in such tangible shape as to be a regular challenge to debate to lookers on.”23

At another level, Cossack, German, English, and, later, Arab and other Eurasian horsemen provided the show a historical rationale for its journeys in the Old World, at once explaining Cody’s long absence in Europe (the American frontiersman had gone to Europe to see old frontiers) and fending off any suggestion that he or his cast of Nature’s Noblemen had been corrupted by their long sojourn in the halls of Culture. In promoting the Rough Riders, Cody’s publicists played up the imminent danger of war along Europe’s convoluted racial frontiers, and held up the Wild West show as a force for peace. Buffalo Bill maintained amity between his company’s “half-savage” cowboys and Mexicans and its warring Indian tribes (all those “Pawnees,” “Arapahoes,” “Crow,” and “Cheyenne,” who were actually Lakota Sioux). He advanced international arbitration as a means to keep the peace between Britain and the United States in 1887. Now, he presented the Wild West show as a calming influence in Europe’s simmering border contests. In 1890–91, some of the cast had wintered over with the show’s livestock “at the foot of the Vosges Mountains in disputed Alsace-Lorraine,” wrote John Burke. Even in 1890, competing French and German claims to the region (which would contribute to the First World War in 1914) menaced “the peace not only of the two countries interested but of the civilized world. . . . What a field for the vaunted champions of humanity, the leaders of civilization! What a neighborhood wherein to sow the seeds of ‘peace on earth and good-will to men.’ What a crucible for the universal panacea, arbitration!” 24

Back in the United States, the constant reference to armed European frontiers assisted Cody’s imposture as world peacemaker, a pose which balanced the show’s increasing militarization. The Congress of Rough Riders of the World offered a synthesis of world history, in which mounted race warriors clashed in grand Darwinian combat from the Old World to the New. Its Cossacks, gauchos, and European military riders appeared alongside its premier attraction, the New World cowboys and Indians, reinforcing the show’s traditional emphasis on the East-to-West course of American history by suggesting a historical movement of an ancient, ongoing race war from Eurasia to North America, echoing the stories of Anglo-Saxonists and Aryanists alike.

At the most superficial level, the champions of this unending race war were cowboys, the show’s version of distilled whiteness, despite all the nonwhite men who actually road as cowboys in the show.25

Whatever the racial composition of the participants, the horseback stunts of the new contingents were so striking that the word “centaur” sprang from publicity even more often than before. The galloping gaucho was “a near approach to the mythical centaur,” like “the North American Indian, the Cowboy, the Vaquero, the Cossack, and the Prairie Scout.” Gauchos wrapped their bolas—leather thongs with iron balls at each end— around posts from sixty feet away, and subdued fierce broncos by riding them in pairs. Cossacks stood on their heads in the saddle, hung off the sides of their horses until their heads brushed the ground, and stood on the backs of galloping horses, slicing the air with powerful sweeps of their swords.

Hailing from the Old World, the show’s new racial segments were practically living ancestors of the American cowboys, but they were degraded by miscegenation that blurred the ancient race frontiers they supposedly guarded. Cossacks were widely known in the United States as semi-civilized (or semi-savage) warriors from the Russian Empire. In reality, they were often as racially ambiguous as American range cowhands. But in Cody’s show Cossacks were “of the Caucasian line.” They were “the flower of that vast horde of irregular cavalry” that the czar had “planted along the southern frontier of the Russian Empire” to contain Asiatic enemies. But programs also said they miscegenated with Muslim Circassians, until they were “as much Circassian as Cossack.” Exactly how white they remained was left for the audience to decide. One London writer saw through the Cossack disguise, reporting (truthfully), that they were trick riders from the province of Georgia, and not actually “Cossacks” at all. Another, who had substantial experience with Russian Cossacks, surmised, “Their peculiar accent and unmistakeable gestures, as well as certain movements in their dance, created a strong suspicion in me that they are Caucasian Jews.”26

Of the frontier originals on display, the only racially “pure” contingents were cowboys and Indians. The racially degenerate Cossacks, gauchos, and Mexicans suggested the constant threat of race decay that awaited racial enemies who forsook combat long enough to embrace.

The white American cowboy, a master of the frontier whose blood remained unmixed, would conquer the world, ushering in the new millennium of white civilization, itself signified in Buffalo Bill’s “conquest” of Rome and the Old World, now recounted in show brochures and memoirs. Cowboy horses were as racially pristine as the cowboys themselves, and publicists went to great lengths developing a theory of equine evolution that paralleled the show’s history of frontier whiteness. Each year, Cody replenished the show’s stable through off-season purchases of horses that would look right in the ring. But in the Rough Riders’ debut season, their horses were said to be a “race” descended from the horses of Cortés, on the backs of which the first conquistador appeared as a “four-legged warrior.” Dissatisfied even with this pedigree, John Burke reached into dim mists of the primeval, to the ancestor of all horses, an animal that was polydactilic, that is, multitoed. “Some instances have been known in modern times, and ancient records give stories, of horses presenting more than one toe. Julius Caesar’s horse,” he wrote, “is said to have had this peculiarity.” Caesar’s horse inspired ancient Roman soothsayers to predict “that its owner would be lord of the world.” Horses of the Wild West show (newly returned from the conquest of Rome) were mustangs of the Southwest, whose peculiarities similarly portended American power. “Most of the polydactyl horses found in the present day have been raised in the southwest of America, or from that ancestry bred.” 27

As racially distilled men, hardened in frontier combat, astride animals in whose veins pulsed the blood of ancient, world-conquering horses, cowboys were bulwarks against the modern age and all its miscegenated, manufactured, and artificial blandishments. They and their nation were bound for glory.

Buffalo Bill’s entertainment was only one of many to valorize frontier race heroes as repositories of national virtue in the age of the mongrel city. Novelist Owen Wister contrasted cowboys, “Saxon boys of picked courage,” with immigrants, those “hordes of encroaching alien vermin, that turn our cities to Babels and our citizenship to hybrid farce.” 28 The Congress of Rough Riders reinforced white supremacy as the culmination of world history, and thereby affirmed the subordination of immigrant ghettoes, as well as the segregation of races, Jim Crow laws, and the tidal wave of lynchings which swept the nation in the 1890s.

ALL OF WHICH makes surprising how much the show now appealed to immigrants, too. As immigrants and their American-born children increased in numbers, they confronted Anglo-Saxonism and American racism not by demanding separation or cultural exclusiveness, but through rituals of assimilation. One of the most popular ways of asserting American identity was by going to public amusements, where immigrants were so numerous that they were now an economic force. 29 A glance at Brooklyn makes this point. In 1890, the U.S. census enumerated 806,343 Brooklyn residents. Over 260,000 of these—one-third of the populace—were foreign-born. One-third of these, the largest immigrant group, were Germans, who numbered 94,000. Another 90,000 were Irish. 30 Some saw the show, or heard about it, during its European tours. Even before the show debuted, many were drawn to America partly by fantasies of lawless frontiers (where there were no punitive elites to demand taxes or labor), abundant buffalo (free meat), and easily dispatched Indians (people even lower down the social ladder than European peasants). In the 1880s, the show’s best seats cost fifty cents, too much for most immigrants. But the cheap seats, at twenty-five cents, were within reach, if barely.31

Ethnic affinity with Rough Rider contingents increased the show’s appeal for Germans, and other immigrants, too. We may speculate that during the show’s six-month stay in Brooklyn, German Rough Riders, the cuirassiers, relaxed in Brooklyn’s many German beer gardens, and found a semblance of the homeland in the “Klein Deutschland” of the Williamsburgh neighborhood. In Milwaukee, home to a large German population, immigrants jammed the stands and cheered the cuirassiers in 1896. Perhaps there were Arabs, such as the Syrians who moved into lower New York in the 1880s, who forged American identities through the debut appearance of Arabs in the show in 1894. At least one of these performers saw his Wild West tenure as a ritual of Americanization. George Hamid was a Lebanese immigrant and acrobat who became owner of the Hamid Morton Circus, as well as of the Steel Pier in New Jersey and the New Jersey State Fair, on his way to becoming “the king of the carnival bookers” by the 1940s. He traced his success to his first job in American entertainment, in 1906, when he began his stint as a “Riffian Arabian Horseman” in the Congress of Rough Riders (he also told a tall tale about learning to read from Annie Oakley—who had left the show in 1901, and probably never had anything to do with George Hamid).32

The stories of Germans and of Hamid are compelling, but whatever the strength of ethnic bonds between immigrant audiences and their Wild West counterparts, some immigrants—especially the Irish and Germans—were drawn also to American performers as naturalizing symbols. Where Remington and Wister saw cowboys and soldiers as a last bastion of Anglo-America in an immigrant world, the cowboy and army contingents fairly bristled with Irish and German names like McCormack, Gallagher, Ryan, McPhee, Shanton, Schenck, Franz, and Kanstein.33 Irish and non-Irish readers alike could imagine themselves as frontier Indian fighters, when “Trumpeter Connolly, of the Seventh Cavalry,” recounted his sanguine experience at Wounded Knee for a newspaper reporter. These ethnic names reflected the presence of Irish and German immigrants in the actual West, and the maturation of their descendants as Americans.34

The challenges of becoming native to a new country seem to have been on the minds of Germans in another way. A few surviving reviews from the German American press suggest that the presence of German soldiers, who are barely mentioned, was less important to German immigrants than the show’s tour of Germany, which was recounted in detail. In a sense, the show’s tenure in Germany gave the Wild West a cachet with German immigrants through a naturalizing process that mirrored what German immigrants hoped to experience in the United States. One reviewer explained, with some enthusiasm, that the show had recently wintered over in Bennefeldt, in Alsace Lorraine. The following spring, “when Col. Cody returned to Bennefeldt, his cowboys had almost become German.” At the same time, Cody’s press agents reached out to Germans by speaking of German American cities as worthy counterparts to citadels of German culture in Europe. “Milwaukee is the only city in the United States that can be compared to a German city,” John Burke flattered the reporter from Milwaukee’s Deutsche Eindrucke, “and rightly deserves to be called the Munich of America. In no other city do you find the age old German charm that dominates here.”35

Indeed, Cody himself might have been as appealing to immigrants as to native-born whites. His ancestors were English and Breton French, but in 1899, his younger sister Helen Cody Wetmore wrote a new biography of him in which she traced the family lineage to ancient Irish kings. How she came upon this story is not clear, and perhaps most immigrants never heard about it.

But even if they were unaware of Cody’s putative Irish roots, Cody’s white Indian imposture was a powerful symbol among the Irish. London audiences equated Indian and Irish savageries to deride the Irish. But in the United States, the Irish were so thoroughly urbanized that competition with real Indians was not a factor in day-to-day life. Comparisons of Irishmen and Indians were less insulting to immigrants, and even had some romantic potential. Irish ward politicians dominated New York politics for decades after taking over Tammany Hall, the New York gentleman’s society named for a seventeenth-century Delaware chieftain. Through the 1890s, every May 12, or “Tammany Day,” the increasingly Irish membership of Tammany Hall—who called themselves “braves”—paraded the streets with painted faces, carrying bows, arrows, and tomahawks. Newspaper correspondents joked about meetings between Buffalo Bill’s Indians and the “great chief” Dick Croker, the Irish-born boss of New York’s Tammany machine.

Among Irish Americans, then, symbols of Indianness and white Indianness were easily adopted, and adapted, to signify (in no particular order) political power, American identity, ethnic unity, a “noble” past, and Irish oppression at the hands of British and Americans alike. When Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders opened in Brooklyn, notables in the boxes included not only the mayor of the city, but A. W. Peters, “chairman of the General Committee of the Tammany Society, and Patrick O’Donahue, another magnate in the New York Democracy.”36

In a sense, the potential for inclusiveness in the Rough Riders was greater than in the old Wild West show, as Cody and Salsbury constantly adopted new Rough Rider contingents to resonate with current events, especially wars. Cody recruited Japanese soldiers during the Russo-Japanese War of 1905, and Cuban insurgents and Filipinos as conflicts in their homelands began. But as savvy as the technique was for recharging the show’s authenticity, it paradoxically created frictions and imposed new limits on the show’s appeal for old fans. In 1901, the Congress of Rough Riders incorporated a regiment of Boer veterans from Britain’s ongoing war against the Republic of the Transvaal, in southern Africa. In New York, sympathy with the Boers ran high, especially among Irish ward politicians and city officials. But that same year, Cody also signed a detachment of Canadian Mounties, who were allied to the British in the war against the Boers. Show managers hired these mutual enemies as a means of refreshing Cody’s peacemaker image, extending his old claims to having brought warring tribes into amity in the interests of educating the public.

But just as hiring real Indians continued to place Cody’s amusement in the midst of political battles between the army and the Indian Service, the practice of hiring imperial troops and colonial rebels entangled the show in bitter politics. In the afternoons before opening in a new town, the show cast often paraded through city streets to drum up public enthusiasm for the show. Irish officials in the police commissioner’s office denied Cody a permit for the cast parade, on the grounds that a “strong sentiment against the presence of British soldiers in the Street[s] of New York” made his Canadian Mounties a threat to public order. Salsbury was livid. He and Cody managed to have the decision overturned, but the incident suggests how tapping into the drama of ongoing wars around the globe both provided a range of identities and attractions for an ethnically diverse audience (Boers as anti-British heroes to the Irish) but also threatened to trap the Wild West show in complex webs of ethnic and imperial contention.37

Moreover, for all the ways the Rough Rider spectacle spoke to immigrants, it probably appealed even more to the American-born children of immigrants, a new population that was gaining in political and cultural influence. By 1890, there were over 300,000 American-born children of immigrants in Brooklyn. 38 By the time Cody’s show camp pitched its tents in south Brooklyn, they were asserting themselves in the workplace and in urban neighborhoods. As citizens and speakers of English with as much education as most native-born whites, many of them took up clerical positions in factories and warehouses or sales positions in stores. These were white-collar workers, increasingly anxious to separate themselves from common laborers (among whom numbered many of their parents). But exactly where these new Americans stood in the class hierarchy was not clear. The office work they performed had been extremely limited or even nonexistent prior to the massive explosion in industry and the wave of corporate consolidation that swept the country in the last decades of the century. According to Eric Hobsbawm, in the United States this new “petty bourgeoisie of office, shop and subaltern administration” actually outnumbered the working class by 1900.39

Whether they were middle class or working class, white collar or blue collar, the rising prominence and disposable income of the new Americans ensured that by the 1890s, they were taking an ever larger role in Brooklyn elections through the influence of the German-American Association, the German Democratic Union, the Swedish Association, and other civic groups. 40

To this point, few of these people could feel they were part of American history. Native-born Brooklyn elites construed American history, and the history of their city, as a story of New England settlers and their descendants. In 1880, some of Brooklyn’s self-identified New Englander upper crust founded the New England Society in the City of Brooklyn. Taking Plymouth Rock as their symbol, this frankly nativist organization vowed to “commemorate the landing of the pilgrims” and “encourage the study of New England history.” Rather than public-spirited festivals which invited mass participation, they celebrated “Forefather’s Day,” which defined historical connection as family descent.41

The New England Society’s story of America was narrow and exclusive, but it was merely an expression of the dominant narrative of American history in 1894. Anglo-Saxonism reigned, and American history remained mostly a tale of Britons moving west. Irish, Germans, Italians, Poles, Slavs, and others found virtually nothing in this narrative to confirm their sense of national identity in either the Old World or the New.

In contrast, the Congress of Rough Riders appealed to the burgeoning ranks of adult children of immigrants by gathering symbols of Old World nations into its New World frontier spectacle. Caught between classes and between nationalities, these spectators sought escape from ethnic labels and confusing class hierarchies by immersing themselves in a broad “American” public, especially in crowds at the era’s popular amusements, from baseball to vaudeville.42 Ethnic types, or stereotypes, paraded on the vaudeville stage. The clueless German in peaked cap and wooden shoes, the belligerent Irishman, and the carefree Italian were all standards of variety performance by the 1890s. But, as David Nasaw points out, the potential ire of the multi-ethnic audience prohibited the grossest ethnic slurs, and many ethnic German, Irish, and Italian spectators enjoyed these performances because in lampooning the rustics just off the boat, the comedy honored immigrants and first-generation Americans as seasoned residents. The ethnic parody was ultimately unifying, with the diverse ethnics united in bonhomie and camaraderie by the end of the sketch, so that divided urban immigrants could imagine themselves to be part not merely of an ethnic group, but also of a city, or a public.43

Cody’s show of the 1890s encouraged similar sentiments. The Rough Rider display parodied none of its members, but the Wild West show gestured to vaudeville in ways that suggest its ethnic and “racial” teachings should be understood in a spirit of vaudeville unification. Jule Keen, the Wild West show treasurer, was a vaudeville veteran who played a comic German on the stage, and he sometimes inserted the act into the Wild West show (where his rustic German brought laughs to the mining camp just before it was destroyed by cyclone in The Drama of Civilization). 44

Thus, direct ethnic connections to Rough Riders were important, but specific cultural bonds were likely less significant than the wide range of possibilities for affinity and identity created by the show’s ethnic and racial variety. In 1893, the show’s opening number, a “Grand Review of Rough Riders of the World,” consisted of a high-speed, choreographed equestrian display in which “Fully Equipped Regular Soldiers of the Armies of America, England, France, Germany, and Russia” galloped through the arena. By 1894, that opening was itemized more variously. The “Grand Review” now introduced “Indians, Cowboys, Mexicans, Cossacks, Gauchos, Arabs, Scouts, Guides, American Negroes, and detachments of the fully equipped Regular Soldiers of the Armies of America, England, France, Germany, and Russia.”45

Even where they had no direct linguistic or other cultural tie to these Rough Rider contingents, the kaleidoscopic, multiracial Rough Rider spectacle provided an increasingly diverse public with a visual frontier myth extending beyond the Anglo-Saxon-versus-Dark-Savage narratives of earlier writers and artists, and far beyond the Plymouth Rock fetish of New Englanders. To be sure, the show walked a fine line, confirming for white Americans that their cowboys reigned supreme, but presenting European contingents as progressive, noble warriors and descendants of historic frontiersmen. Whether one had been born in Europe or in America, to see the Congress of Rough Riders was to imagine one’s people as hardy, powerful, armed horsemen.

In 1894, the show still included many of its Wild West acts, such as the “Attack on the Deadwood Coach,” “Cowboy Fun,” shooting by Annie Oakley, the “Battle of the Little Big Horn,” the “Attack on the Settler’s Cabin.” But it also incorporated a military musical drill, featuring the Seventh U.S. Cavalry (Custer’s regiment, which also appeared in the “Battle of the Little Big Horn”), and the British, French, and German contingents. The “Riffian Arabian Horsemen” performed high-speed riding and juggling of rifles and swords, along with tumbling displays. The old horse races between cowboys, Mexicans, and Indians now featured “a Cowboy, a Cossack, a Mexican, an Arab, a Gaucho, and an Indian.”

The effect was not only to Americanize the global frontier, justifying American empire, but also to internationalize the American frontier, inviting once-excluded peoples into the American myth. With the cowboy reigning supreme, the Indian the lowest on the ladder, and everybody else somewhere in between, the Congress of Rough Riders expressed the white supremacy and national chauvinism of most Americans.46 Just as the cowboy conquered Indians, so he had conquered the world. And yet, by bringing more people under its awnings and into its mythological canvas, the show provided the diverse residents of the divided city of Brooklyn, and other cities where it played, a powerful sense of belonging, or at least the potential for belonging, to their new nation, its history, and its public.

In this sense, Cody’s development of the Congress of Rough Riders paralleled the work of scholars and writers who were broadening American history to incorporate generations of immigrants traditionally excluded from Anglo-Saxonist narratives. Inoculating himself against the sting of Anglo-Americanism in his six-volume Winning of the West, Theodore Roosevelt wrote his forebears from the Netherlands into the ancient tribes of Anglo-Saxons whose descendants settled the United States.47

More significant for the development of American history as a discipline was the work of Frederick Jackson Turner, who delivered his classic essay, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” at the same Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition where the Congress of Rough Riders debuted in 1893. In an exploration of the frontier and its recent closure, Turner argued that “free land” was the defining condition of American history, and that along its westward-moving edge American society went through a continual process of social evolution, from hunter to industrialist. The essay caught the era’s intellectual anguish over the rapid modernization of America, but it also shaped a generation of historical scholarship, making the history of the American West into a major academic field.48

In the decades since, critics have rightly taken Turner to task for his overemphasis on manly white actors and for his vague and contradictory use of terms. But none of that detracts from how adventurous he was in opening his historical frontier to people who were not Anglo-Saxon. His mentor, Herbert Baxter Adams, had extolled, in essays like “Saxon Tithingmen in America” and “The Germanic Origin of New England Towns,” the wonders of Saxon institutions as they were transported to the United States. Adams was, in a sense, writing from the same script as the New England Society of the City of Brooklyn, making the Puritans into hardy Anglo-Saxons, both fulcrum and lever of American history.49

Turner turned the story of American history around, arguing that Norwegians, Swedes, Germans, English, and others had been transformed into Americans by the process of “winning a wilderness.” Among its inspirations were Turner’s vivid memories of his hometown of Portage, Wisconsin, which was surrounded by Norwegian, Scottish, Welsh, and German settlements, and whose townspeople, as he knew them in the 1870s and ’80s, were a “real collection of types from all the world, Yankees from Maine & Vermont, New York Yankees, Dutchmen from the Mohawk, braw curlers from the Highlands, Southerners—all kinds.”50 Turner’s “types from all the world” look substantially white to modern readers, but they were only tenuously white in the days their ships were docking at Ellis Island, and they had little or no claim to Anglo-Saxon traditions. True, Turner removed Indians from his story except as an obstacle to be overcome, and his frontier thesis had no place for Mexicans, nor for the mostly urban “new immigrants” from southern and eastern Europe, nor for the Chinese or other Asians. But even so, “The Significance of the Frontier,” like Cody’s Congress of Rough Riders, was a myth-busting punch at the Anglo-Saxonist orthodoxy, an attempt to broaden American history beyond its narrow racial tie to Britain, and to incorporate at least some American-born children of immigrants into national history and myth.

The revamping of historical myth in Cody’s arena suggests how much the quest for larger audiences has shaped portrayals of the American past. The discipline of American history emerged in American universities only in the last few decades of the nineteenth century, at the same moment that the term “show business” was invented to describe the emergent industry of entertainment.51 Turner and Cody were on opposite sides of the same historical coin.

On the facts, the Congress of Rough Riders was no more persuasive than Turner’s thesis. The notion that all peoples were “warriors” embroiled in ceaseless race conflict was a social Darwinist conceit with little connection to the lives of real, mostly urban immigrants and their children. Cody’s new story had no place for any ethnic group that had no horseback tradition. Except for the brief exceptions like the inclusion of the “Magyar Gypsy Cizkos” in 1897, which may have beckoned to eastern Europeans, the show was far more inviting to northern and western European immigrants, like the Irish and Germans, than it was to the “new immigrants” from southern and eastern Europe. (Cossacks, after all, were shock troops of the czar and persecuted many Russian Jews who emigrated to America.) But none of this detracted from its appeal as a somewhat more inclusive visual myth of global frontiersmen, so varied and diverse that one could see the show as a template or reflection of polyglot America, the enactment of a more democratic myth for a more diverse nation.

And yet, there were limits to the show’s ability to influence popular historical narratives. Sitting a horse in the Rough Rider show proved no guarantee of a place in popular western myth. The absence of historical consciousness about one Rough Rider contingent remains striking. Show programs note the appearance of “American Negroes” in 1894 and 1895. In 1899, black veterans of the Cuba campaign reenacted their exploits in the “Battle of San Juan Hill.” Show programs mention “American Negroes” through the early 1900s, suggesting that African Americans have a history in the show that awaits further research. In 1900, two white soldiers from the show’s U.S. Artillery detachment were shot and wounded in a brawl with town police in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin.52 Dexter Fellows, a Wild West show press agent, recalled that the fight erupted when a white U.S. cavalryman, a German cuiriassier, and “a burly black in charge of a detachment of Negroes from the Ninth Cavalry” were challenged by a drunken deputy constable “who could barely speak English.” Fights between circus performers and local police were hardly news, but since barely restrained violence and gunplay were more central to Wild West appeal than to other traveling amusements, this explosion of public violence threatened to frighten crowds away. Fellows worked overtime to soothe excited correspondents after the episode.53

The mix of immigrant, native white, and native black figures in this incident (and the absence of Indians from it) suggests a complex mixing of messages about possibilities for American identity within the show. The immigrant deputy constable hints at that rising generation of immigrant children who were increasingly in evidence among the audience.

But what did the presence of black U.S. soldiers among the Rough Riders say to the audience about African Americans in American history? Show publicity barely mentions them. Newspaper correspondents spoke of them almost not at all, and scholars of the show seem to have overlooked them entirely. There are many photographs of cowboys, Indians, Cossacks, and a few of Mexicans in the show. Images of cowgirls are not rare. But a paltry handful record the presence of the buffalo soldiers. Did African Americans attend the show? If so, we may assume they were segregated, as they were at circuses and other traveling amusements. But why did so few notice their presence in the arena? Why have these Wild Westerners been largely forgotten?

The most likely answer is that African Americans had no story of their own in the Wild West myth, which was essentially made of three strands. Indians were the dispossessed noble savages who once roamed the prairies. Mexicans were the descendants of the first people to encounter Indians, the Spanish who fell into decadent race mixing and failed to properly conquer them. Cowboys were the vanguard of the white race who succeeded Mexicans, and finally brought progress and civilization west.

There was no black component to that tripartite narrative, and Cody’s modification of his message in the 1890s did not address that shortcoming. The Congress of Rough Riders gave every detachment a genealogy that originated among ancient horsemen—gauchos from Spanish conquistadors, Cossacks from “the Caucasian line,” Arabs from the horsemen of the desert who appeared even in the Old Testament. But not black soldiers. They merely appeared in the show lineup, with little or no explanation.

In real life, blacks had fought Indians, trapped beaver, hunted buffalo, cowboyed cattle, built homesteads, and run almost every form of commercial outpost in the U.S. West. They had also joined Indian tribes, married Indians, and fought American expansion. They had, in other words, done everything that whites and Mexicans had done (there were black Mexicans, too) and sometimes more. Their absence from narratives of western history would become a standard failing in academic halls and popular culture alike. With the Old West as the crucible of white American virtues, and with western mythology an escape hatch from the contemporary political impasse of Reconstruction and the segregation of Jim Crow, blackness was not something easily incorporated into the western story.

All of which makes it even more interesting that Cody tried to put blacks into the show at all. He seldom spoke of black people. He scouted for black cavalry detachments in the West, and he knew their virtues. But his autobiography derided black soldiers as cowardly and childlike. Neither Cody nor Salsbury ever explained why they incorporated buffalo soldiers into the Wild West show in 1894 and after.

But if the Congress of Rough Riders represented a savvy attempt to keep pace with an ethnically expanding public, there are some pretty good clues that the proprietors foresaw black spectators as potentially a large part of that public, too. Like the Rough Rider appeal to immigrants and firstgeneration Americans, such a gesture would need to be shrouded in white supremacy. But if blacks could be included in a way that did not offend whites, there was a possibility of drawing even bigger crowds.

These may have been the considerations that motivated Cody and Salsbury to plan a new show of African American history in 1894, hoping it would appeal to black audiences and the public at large. Black America opened at Ambrose Park in 1895. The attraction was billed as a “Gigantic Exhibition of Negro Life and Character,” showing “the Negro as he really is . . . placed in the amusement world as an educator with natural surroundings.” With a display of black people moving from “savage, to slave, to soldier, to citizen,” the show rationalized slavery as the necessary passage for savage people (featuring “reproductions of life in Africa,” complete with “native African dances”) but also valorized black fighters for the Union during the Civil War. Urged the poster, “Come and see the best drilled cavalry company in the United States.” 54

Cody himself was excited by the new enterprise, which he described in terms suggesting that it would combine minstrelsy and history. “Negro humor and melody will in this show reach the acme of perfection,” he told a newspaper reporter. The spectacle would feature “phases of plantation life.” Presumably, some of these were happy enough to allow audiences to enjoy the singing. Others would show “the auction block and the whipping post.”55

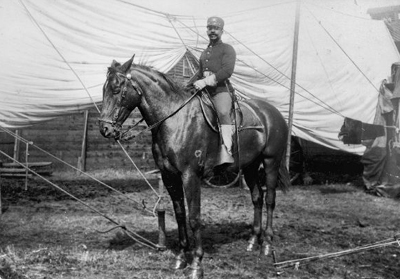

Unidentified Wild West show buffalo soldier, c. 1900. Cody and Salsbury introduced African American cavalry veterans, “buffalo soldiers,” to Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World in 1894. Because they didn’t have a thread of their own in the mythic tapestry, the press seldom recognized them, and their contributions to western settlement and the Wild West show both have been largely forgotten. Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

Black America failed, and it is not hard to see why. The humor and condescension of minstrelsy allowed little pathos on the issue of slavery. The show’s comic elements sat uneasily alongside representations of black misery (and white savagery) at the whipping post and auction block, and of black valor and heroism in the fight for the Union and emancipation. In the Wild West show, Indians were easily admired. White homeowners and job seekers in Brooklyn and elsewhere did not compete against Indians. Moreover, since Indians were vanishing, they would not need to compete against them in the future, either.

But black people coming into their own in Black America were another matter. African Americans competed with immigrants and whites for jobs in urban New York. There were just over 11,000 black people in Brooklyn, and 24,000 in Manhattan. Resisting black advancement was a primary criterion of whiteness. An amusement depicting black people making progress, showing their advance, hinted that they might have an equal right to some share of wealth in greater New York. Even if African Americans found some attraction in it, it was likely too expensive for most, and in any case its cast of six hundred was too expensive to support on a relatively small segment of the mass public. (There were only 70,000 African Americans in all of New York state.) For true believers in white racial identity, a show of black progress made no sense. Blacks had no history. Whiteness claims history for its own.

Black America lost money. Cody urged Salsbury to give it more time. “I am putting every dollar I make” with the Wild West show “into Black America,” he wrote.56 But within weeks, the show closed. A newspaper correspondent later reported that Nate Salsbury “spent enough money to free Ireland in organizing ‘Black America,’ with which he thought to charm the people of the North.” Instead, “the venture . . . cost him $110,000 and convinced him that the white man has no use for his colored brother except for the twelve hours immediately preceding the closing of the polls on election day.” 57

Unidentified buffalo soldier and cowboys emerging from Wild West show tent, c. 1900. Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

FOR ALL ITS APPEAL to immigrants and first-generation Americans, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West targeted the urban middle class who were, to say the least, extremely enthusiastic about the addition of the Congress of Rough Riders. The long stand of 1894 provided the public with opportunities for return visits, and more newspaper commentary than when the show was traveling. Cody and Salsbury chose the Ambrose Park showground for its accessibility to large audiences and the press. Seeking to replicate the success of the 1893 summer in Chicago, Salisbury cut a deal with the Thirty-ninth Street Ferry company to lease a twenty-four-acre parcel next to the ferry docks in south Brooklyn. For six months, spectators steamed from Manhattan or any of the other New York communities directly to Ambrose Park, or they crossed the Brooklyn Bridge and made their way south to the showground on the trolley line. The result was an outpouring of journalist commentary on Buffalo Bill, his Wild West show, and his colorful, heroic cast and their camp, which was dutifully preserved by show personalities who jammed their scrapbooks full to bursting with newspaper clippings. In earlier years, reviews focused on the arena performance and on the adventures of cast members, especially Cody, in the cities the show visited. But by this time, the Wild West camp itself had become a place, a space understood through stories told about it. In 1894, with six months of exposure to the camp, journalists delved deep into the show’s symbols and meaning.58

We must be wary of reading too much into those stories. Many of them were planted by John Burke, Cody’s longtime press agent and every journalist’s best friend, who sat with press delegations telling stories and amusing anecdotes and the history of the show for hours on end, day after day. Sometimes Burke concocted new stories; other times he encouraged journalists to recycle other writers’ material. Sometimes correspondents came up with original stories (which Burke then read and, if he liked, trumpeted as his own). His blustery, jovial narratives inspired miles of newspaper columns, which transmitted the show’s messages to the hinterlands. These accounts were the dominant mode of understanding Buffalo Bill’s Wild West even for people who only got to spend one afternoon with Cody and his massive entourage, and for those who never saw it at all.

Much press commentary focused, as it always had, on the savage and semisavage Wild Westerners and their encounters with the city. Indians, gauchos, “Riffian Moors,” and cowboys ventured to schools, newspaper offices, and other modern venues, always in awe, in recurring expression of the civilizing virtues of the city, and the wide-eyed wonder of rustics at the fast pace of urban progress.59

But by 1894, more than in previous years, the show camp itself was the main attraction. Show tickets and other publicity encouraged spectators to arrive up to two hours early and tour the bizarrely placid settlement which was no mere agglomeration of people, but a living representation of progress, against which audiences could measure the historical, social, and political advancement and meaning of their own communities.60 Here they could see buffalo, Indians, cowboys, and perhaps meet Annie Oakley or any of the other leading lights of the show.

In 1894, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West had (or claimed to have) a population of 680 people, including performers and support staff. Journalists called it “a little tented city.”61 Some called it “the White City,” as if the World’s Columbian Exposition’s moral messages about the supremacy of American civilization and its greater destiny were now conveyed by the Wild West show.62

Indeed, Buffalo Bill’s frontier simulacrum seemed to anticipate the modern city at least as much it recalled the vanished frontier. In London, in 1892, Frederic Remington mused on the meaning of the Wild West camp for modern urbanites. “As you walk through the camp you see a Mexican, an Ogallala, and a ‘gaucho’ swapping lies and cigarettes while you reflect on the size of the earth.”63 The catalogue of disparate races, thrown together in one place, implied violence and primitivism—but it also echoed a standard device of writers seeking to convey the racial anarchy of the modern city. The reformer Jacob Riis published his photographic exposé of immigrant ghettoes, How the Other Half Lives, in 1890, the very year the U.S. Census Bureau declared the frontier closed. He spoke of the tenements—“where all influences make for evil”—as a kind of replacement frontier.64 (Indeed, Riis himself was an immigrant from Denmark, and such a fan of James Fenimore Cooper that when he arrived in America in 1870, he strapped a giant navy revolver to the outside of his coat—à la Hickok—and sauntered up Broadway, expecting to find “buffaloes and red Indians charging up and down.”) 65 In lower Manhattan, he wrote, one could find “an Italian, a German, a French, African, Spanish, Bohemian, Russian, Scandinavian, Jewish, and Chinese colony . . . The only thing you shall vainly ask for in the chief city of America is a distinctively American community.”66

When Riis searched for a “distinctively American community,” he meant a neighborhood of English-speaking, native-born Americans. Cody’s “little, tented city” was not that. But, as Amy Leslie and other critics had observed at the World’s Columbian Exposition, it represented, for all its racial primitivism, a kind of ideal American community: a spectacle of racial anarchy wrought into progressive order by American frontier genius.

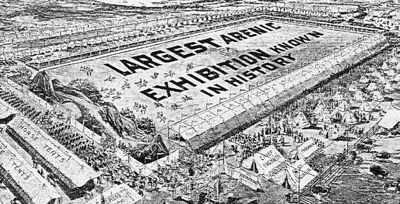

“The Little Tented City.” The Wild West camp became the premier attraction of the show, tantalizing visitors with a view of America, its frontier past, and its technological, professionally managed future. Note the electric generator in the foreground, not far from the buffalo pen, suggesting the fusion of nature and technology in Cody’s entertainment. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West 1898 Courier, author’s collection.

The Wild West camp consisted of rows of tents along paved streets and cinder walkways between and among flower beds and small gardens, and to tour it was to contemplate both the frontier past and the urban future. 67 The disparities between Indian tipis and the modern amenities of Cody’s tent— “the size of a small farm house,” and divided into rooms, according to one reviewer—were themselves a lesson in the material advantages of civilization and progress. In Cody’s tent, “we see a telephone, curtains, bric-a-brac, carpets, pictures, desks, lounges, easy chairs, an ornate buffet, refrigerator, and all the furnishings of a cozy home.” By contrast, in a tipi standing nearby “we see a circular board floor (it should be dirt) within a ring of canvas. On a sheet of metal are the smouldering embers of a fire that makes a tepee at once a home and a chimney.” To visit first one and then the other “is to be able to compare the quarters of a modern general with the refuge of a Celtic outlaw in the seventeenth century. By just so much have we advanced; by just so much has the Indian stood still.”68

But there was more than frontier history on display. The construction work required by the show was touted as an achievement and spectacle in its own right, a display of the show’s ability to transform the city.

In 1894, the camp’s transformation of south Brooklyn also conveyed important messages about the show camp’s civilizing mission. “The interior of the grounds was a surprise,” wrote one visitor, “for on the large plot of waste land there has been laid out a beautiful summer park, with trees, shrubbery, flowers, and beautiful paths.”69 At various times, the Wild West appeared not only near but in gardens, as in its appearance at London’s International Horticultural Exhibition in 1892. Although modern readers might find the pairing of broncos and buttercups an odd contrast, in the late nineteenth century they were bookends for the story of civilization, which began in savage nature and culminated in the garden. Proximity of show to gardens echoed its domestic culmination, the salvation of the settler’s cabin and the replacement of the wilderness with the pastoral, and for this reason, landscape gardening was a major activity amid show tents and tipis.

The mix of urban and pastoral at Ambrose Park resembled what many urbanites desired for their own exploding industrial cities. New York’s reformers often pointed to the city’s lack of parks and greenery as a source of social degeneracy. According to Jacob Riis, the common street urchin, that “rough young savage” who so terrified civil society, became a sweet-natured child in the presence of flowers. “I have seen an armful of daisies keep the peace of a block better than the policeman and his club, seen instincts awaken under their gentle appeal, whose very existence the soil in which they grew made seem a mockery.”70 Park landscapes and urban gardens, like New York’s Central Park, helped soothe the city’s rough modernity. So journalists exulted that “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Company has made a garden spot where a few months ago was the dumping ground of South Brooklyn.”71 Where the Wild West show portrayed the settling of the hostile western frontier, the camp’s balance of Artifice and Nature symbolically “settled” the darker edges of the city.

The bucolic landscaping was a powerful contrast to the supposedly simmering violence of Wild Westerners, which press agents constantly highlighted. Managing Buffalo Bill’s Wild West was nothing like “the management of a light-opera company on the road,” for “the people of the Wild West show . . . are all schooled in the theory that it is the proper thing to run a ten-inch knife into the anatomy of anyone who does not agree with ‘their particular whim,’ ” wrote Frederic Remington.72

Given these popular fixations, we might expect that the show’s large, multiracial cast would foment anxieties about social disorder. But for the most part, the show’s violence did not concern social critics except for its alleged effects on small boys. The boy who sees the show “wakes up the family by uttering weird coyote yells in his sleep. He lassoes a bedpost and the family cat, and fires a toy pistol at imaginary objects while riding the back fence at full speed.”73 The Gilded Age middle class saw rough outdoor play as contributing to the development of manly, entrepreneurial characteristics like social aggression and risk taking, and as protection against “overcivilization.” In any case, the violence of middle-class boys was constrained by the watchful authority of parents and family, so such influences were largely construed as positive. 74

Indeed, in the minds of many, the ways that Buffalo Bill’s Wild West incited such childhood play helped to naturalize urban neighborhoods through an old American ritual: playing Indian. Many reporters echoed the one who described numerous “Indian tribes” of seven-year-old boys along Brooklyn’s upper Seventh Avenue. Here, clotheslines had disappeared as boys made them into lassoes for roping little girls, the trolley became “the Deadwood Stage,” and Tiger Claws, Bounding Elks, Scar-on-Necks, Black Bears, Howling Antelopes, Bounding Eagles, “and other Lilliputian savages” rampaged mischievously through the streets.75 By inspiring such frolicsome “Indianness,” Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show assisted in the transformation of city children into adults who retained frontier virtues.76

Beyond its impact on boys, the show’s seamless performance and generally law-abiding cast provided a spectacle of urban order to audiences concerned about the social chaos of their own city. The contradictions between the primitivism on display and the modern science and technology which made it safe and accessible for audiences created a tension that was dramatic and fascinating in its own right, and a constant feature of press coverage. For most of its life, the Wild West show, like circuses and other large traveling amusements, moved about by rail. During the 1890s, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West required three trains to move cast, animals, support staff, and props. In addition to its hundreds of Indians, cowboys, gauchos, Cossacks, vaqueros, European cavalrymen, and other performers, the show employed ranks of skilled and unskilled laborers. Everywhere the Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders went, they brought along wheelwrights, harnessmakers, blacksmiths, ticket sellers, watchmen, butchers, cooks, pastry cooks, wood choppers, porters (to tend employees on the trains), drivers (to transport cast members and other workers from train to showgrounds and back again), canvasmen, and stake drivers, among others. All told, the Wild West show required almost 23,000 yards of canvas and twenty miles of rope.77

Correspondents at home and abroad seemed never to tire of watching crews load and unload the cars, which was a popular diversion and a means of thinking about the show as a modern organization, as hundreds of men raced back and forth unloading materials and animals, erecting tents, stabling horses, and installing the traveling kitchen in a whir of precision that evoked nothing so much as a factory.78 Newspapers extolled the wonders of Wild West show mobility during the 1880s, and after 1894, as the show went on the road for one- and two-night stands in towns across the country, its spectacle of a community-on-the-move became a major attraction again.

Meanwhile, in Brooklyn and at other long stands, public attention to the camp’s technology, social engineering, and scientific management underscored the modern relevance of a show featuring pre-modern conflict. A few examples make the point. Hoping to avert the harrowing losses from disease which plagued the camp during the European tours, Cody and Salsbury ordered vaccinations of the show cast in Brooklyn, making the Wild West camp a model of modern public health for some observers. “Cleanliness and perfect order are two cast-iron rules in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West camp,” wrote a reporter on the visit by doctors from the Brooklyn Health Department to administer the “cosmopolitan vaccinating bee.”

Columnists lionized Buffalo Bill Cody and Nate Salsbury for this scientific attention to public and employee welfare. But just as significant, the response of the show’s cast to the vaccinations provided lessons for the larger city. Although the Indians were “so full-blooded that the least scratch will cause a profuse flow,” they submitted willingly. Cossacks, gauchos, cowboys, and “half a dozen Arabs, and as many beautiful Arabian women, negro cooks, and helpers” also went calmly to the needle. The bravado, or at least acquiescence, of the Rough Rider camp stood in sharp contrast to the response of Brooklyn’s immigrant neighborhoods in recent vaccination campaigns. During various public health alerts, authorities in greater New York attempted to vaccinate whole neighborhoods. Immigrants distrusted both vaccination and city authorities, and their response was not always cooperative. In Williamsburgh, Brooklyn’s large German neighborhood, immigrants hurled “hot water and ‘cuss’ words” at doctors who tried to vaccinate them.

The cooperation of the Wild West camp suggested that the most primitive and potentially violent of peoples could be brought to the benefits of public health through the governance of white men like Cody and Salsbury.79 Most of all, the complacent acceptance of the needle among the show’s Germans, Indians, and other “savage” or “half-civilized” peoples implied messages for the white-collar enterpreneurs and managers who were the show’s primary audience. Brooklyn’s troublesome immigrants might yet be brought into the new medical and scientific order which the city’s English-speaking professional bureaucracy were applying to the cities. For the reading public, the multiracial and potentially violent city teeming at the show gates could also be tamed by the proper application of authority, managerial skill, and frontier spirit.

The popular interest in public health was accompanied by professional interest in the show’s infrastructure. In the historical narrative of the show’s arena, old technologies like the Deadwood Stage rumbled their last before crowds anticipating new technologies. But that story came to the public through application of those new technologies, and fascination with them made Cody’s camp seem both an exhibit of the primitive and a cutting-edge outfit, particularly in its use of the revolutionary technology of electricity.

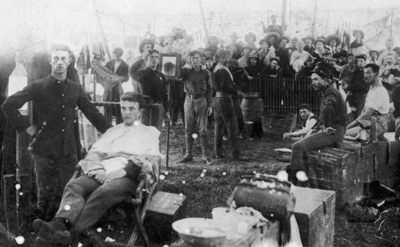

Buffalo soldiers, vaqueros, Indians, and the rest of the cast in 1896. The diningtent was the center of the show community and a frequent subject of commentary, as a place where the heterogeneous community of the Wild West show was welded into social order. Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

Edison, Westinghouse, and others began to light up the cities during the early years of Cody’s show. Urban dwellers had once feared nighttime in the city as frightening, dangerous, and potentially lewd. Then, in 1886, the Statue of Liberty lit up with electric light (as did the stage lighting in Cody’s Drama of Civilization, at Madison Square Garden), and in 1893 the electrical lighting and electrical amusement rides of Chicago’s White City startled and impressed millions of visitors, and thousands of columnists.80

Electrification of the city engendered a new order of night life and public entertainments. Not only did lights make the city safer, but they created a new landscape of visual wonder, brilliant electric advertisements and white illumination which simultaneously brought new attractions into being and seemingly cleansed the city of grit and dirt which so alarmed reformers during daylight hours. In important ways, urbanites knew the working hours were over, and the time for entertainment and leisure had arrived, when the city’s new electric lamps blinked on, creating the nighttime, illuminated world of “the Great White Way.”81

In Brooklyn, electric lighting had begun to alter the city’s nightscape by the early 1880s, and shortly before the Wild West show came to Ambrose Park, in the early 1890s, electric trolleys began to run on Brooklyn’s busy streets.82 The trolley was the vehicle of the modern era (the name “trolley” came from the device that conveyed the electric current from wires overhead to the car), and it soon became a ubiquitous feature of the urban landscape in Brooklyn as elsewhere. New York City had 776 miles of trolley track by 1890, and even St. Louis had 169. By 1902, Americans took 4.8 billion rides on the trolley.83

The transformation was not easy. Because trolleys were both faster and quieter than stage coaches, wagons, and the old horse cars, pedestrians often misjudged them and paid with their lives. In 1893–94, seventeen people were killed by Brooklyn’s Atlantic Avenue Rapid Transit Railroad alone, and public anxieties about the new technology ran high. Ultimately, it gave rise to the nickname “trolley dodgers” for Brooklynites (later inscribed into the city’s public amusements when it was applied to their baseball team, the Brooklyn Dodgers). Nonetheless, electrification continued, and Brooklynites could take the Third and Fifth Avenue trolley lines to the Wild West show’s front gates.84

In fact, a not insubstantial crowd of observers made this trip to see the show’s electrical works. The Wild West show, exhibition of vanishing skills and organic technique, was literally, and paradoxically, a beacon for electrical engineers. More than two hundred members of the New York Electrical Society accepted invitations to tour the camp’s electrical works and watch the show under its new floodlights, installed and maintained by the Edison Electrical Illuminating Company. Popular newspapers and journals of electrical associations alike recounted these visits and explored the electrical circuitry of the show—“The grounds are lighted by seventy seven 2,000-c.p. [candle power] incandescent arcs, while the buildings and tents require over 800 16-c.p. incandescent lamps.”85 As newspaper writers were fond of reporting, the “Texas,” the electrical generating plant at Ambrose Park, was “said to be the largest for the purpose in the world.” Given the size of the area to be illuminated (the arena comprised two acres), the challenge of providing illumination had been especially great, and the generators reportedly cost $30,000.86

The skillful attentions to the show’s electrical apparatus were the culmination of efforts made by Cody and Salsbury at least since the 1880s. Circuses attempted the use of electrical generators as early as 1879, but they soon abandoned them because they were too difficult to transport. In his earliest letters to Doc Carver, Cody had broached the subject of electrical lighting for the show as a way of making more money, and their performance at Coney Island in 1883 included “Grand Pyrotechnic and Electric Illuminations.”87 The show incorporated electric lights at long stands in Europe, in London and in Glasgow, but the 1894 season marked the beginning of the show’s almost consistent electrification. By 1896, Cody and Salsbury acquired electric generators to travel with the show, and the Wild West “Electrical Department” employed eleven people. In cast parades through the streets, the mobile, gleaming, steam-powered electrical generating plants, called the “Buffalo Bill” and the “Nate Salsbury,” rolled along between contingents of frontiersmen. “The enormous double electric dynamos used to illuminate the Wild West performances are well worth inspecting, as a scientific and mechanical triumph,” trumpeted the 1898 show program. “They are the largest portable ones ever made.”88 Even on the road, managers arranged tours of the electrical equipment, followed by performances, for visiting groups of electrical engineers and utility company officers.89

Nighttime illumination meant the possibility of two shows a day, one in the afternoon and one in the evening, doubling gate receipts without increasing salary outlays. But it had a larger cultural meaning, too. When the show acquired the sanction of leading “scientists” (as electrical engineers were called at the time), it enhanced its mythic relevance for its audiences as both spectacle of the past and harbinger of the future, a complete reenactment of civilization’s rise from nature to technology, the maturation of her people from buffalo hunters to electrical engineers.

Barbershop, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, c. 1890. A widely diverse, orderly company town, the Wild West camp came to represent America itself. Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

The electrification of the Wild West show thus implied a symbolic parallel between show and nation, each of which originated on the frontier and advanced to modernity. The machinery that made the show possible was itself a popular wonder, calling forth a collective emotional and unifying response from observers that approached what the historian David Nye and others call the “technological sublime.”90

In some ways, the Wild West show’s stature was similar to that of the railroad circus. During the 1890s, railroad circuses both imitated and symbolized modern business. They were corporate, technological, hierarchical organizations in which white male owners and operators managed the diverse and the freakish and waged near-constant advertising “wars” in which they plastered entire regions with their posters and handbills, consolidating smaller entertainments beneath ever larger tents and undercutting one another in relentless pursuit of profits. William Cody’s show business career, with its beginnings in a small independent theater company and its culmination in a huge, corporate entertainment, paralleled those of the Ringling brothers, P. T. Barnum, James A. Bailey, W. T. McCaddon, and other circus impresarios who bought, sold, and consolidated traveling road shows in efforts to monopolize the industry. The circus and Wild West show business paralleled still larger developments in the American economy, where smaller concerns and entrepreneurs—shopkeepers and artisans—were shunted aside by the behemoth corporations of Vanderbilt, Morgan, and McCormick in the process that historian Alan Trachtenberg calls “the incorporation of America.”91