CHAPTER SIXTEEN

Empire of the Home

TOURING ACROSS the United States, the Rough Rider spectacle expressed gathering public sentiment for an American empire during this decade of unprecedented overseas expansion that saw U.S. military engagements from Cuba to the Philippines. The American thrust for empire began in domestic strife, a decade of which shaped William Cody’s show and his offstage life in profound ways. In 1893, as the world’s fair wowed the public, the nation was gradually overwhelmed by the worst economic depression in memory. Before it was over, some 8,000 businesses and 360 banks failed. Crop prices were already down, and farmers anguished as they fell even further. Wages plummeted. Jobs disappeared. In the winter of 1893–94, one in five American workers, perhaps as many as three million people (100,000 in Chicago alone) had no work. In the spring of 1894, Ohioan Jacob Coxey led the nation’s first march on Washington, a group of about 100 jobless men demanding unemployment relief. “Coxey’s Army” inspired many followers. In the Far West, large gangs of unemployed men organized themselves into “industrial armies” which intimidated or overpowered guards and rode the rails for free.1

Manufacturers and others blamed the crisis on “overproduction” of goods, on the absence of markets for the abundant sewing machines, bicycles, soap, clothing, and other products pouring from American factories and fields (and so abundantly on display at the Chicago world’s fair). As Americans staggered through the downturn, the clamor for overseas markets began to grow. The frontier was closed. New horizons beckoned, if only America could be strong enough to stave off European empires that threatened to close her out of lucrative commerce in Asia, Africa, and the Pacific. This expansionist surge peaked in 1898, when the United States won a lightning victory in the Spanish-American War, seizing the remnants of the Spanish empire in Cuba and Puerto Rico in the Caribbean, the Philippines in the Pacific, and annexing Guam, Samoa, and Hawaii in the process.

The spectacle of the Congress of Rough Riders of the World kept America’s increasingly imperial stance in the minds of Americans throughout the decade and after. At no point was the flow between entertainment and expansionist politics more obvious than in 1898. Many assume Cody’s Rough Riders took their name from Roosevelt’s. The reverse is true. Theodore Roosevelt’s First Volunteers adopted the Rough Rider name from Cody’s show and took it to the top of San Juan Hill and into American history. Some of Cody’s troupers joined Roosevelt’s troops, and after the war, in 1899, a genuine detachment of Roosevelt’s Rough Riders appeared in the Congress of Rough Riders to reenact their famous charge into the Spanish guns. 2

Although Cody and Roosevelt became passing friends, in the beginning the gauzy overlap between real history and public entertainment masked tensions between them. The aspiring politician staked a claim not only to the charge up San Juan Hill, which practically guaranteed his election to the governorship of New York, but also to the history of the campaign, which he published in The Rough Riders, a lively, self-aggrandizing account that appeared in 1899. In the book, Roosevelt distanced himself from Cody’s show, insisting the Rough Rider name was bestowed by the public “for some reason or other.” He claimed to have resisted it, “but to no purpose,” and when commanding generals began to refer to them by that name “we adopted the term ourselves.”3

These disingenuous denials reflect the antitheatrical leanings of the era’s most theatrical politician (dubbed Theater Roosevelt by some wags). Whether or not he saw Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World, he imbibed freely of its manly regionalism. His regiment’s ideological premise was that a volunteer force of western cowboys, sheriffs, outlaws, Indians, and even some “half-breeds,” combined with a smattering of easterners who were “western” in spirit (including Roosevelt himself), could, through their hardy warrior virtues and their natural self-reliance, perform at least as well as a regular army regiment. Roosevelt’s Rough Riders were as heavy on “real western men” as Cody’s Wild West show, and included their share of frontier army veterans, too (including the aging Chris Madsen, who had been at Warbonnet Creek when Cody scalped Yellow Hair).4

In reenacting the history of a regiment that drew its name from the show itself, the “Battle of San Juan Hill” to a degree reprised Cody’s fusion of historical action and representation in the scalping of Yellow Hair over two decades before. But the gesture to Roosevelt, in deflecting attention onto the blustering politician and away from Buffalo Bill, came with a risk. Roosevelt’s refusal to acknowledge the show as an inspiration was itself a challenge to Cody’s authenticity. Cody’s press agents fired back at TR’s demurrals. If the “manner in which Colonel Roosevelt” introduced the Rough Rider name to the Spanish had “made it historically immortal,” Buffalo Bill’s Wild West had been the first to introduce it to the world. Through Cody’s labors, not Roosevelt’s, audiences had “grown to understand, fully appreciate, and unboundedly admire” the Rough Rider title.5

The spat with Roosevelt may have originated in Cody’s earlier ambivalence about the man, which TR could have read as hostility. When and where they first met is not clear, but the two men circled each other warily after Roosevelt returned from Dakota Territory and ascended to New York political command in the mid-1880s. In 1887, Chauncey Depew told a raucous, pro-Roosevelt meeting of the New York Republican Club, “Buffalo Bill said to me in the utmost confidence, ‘Theodore Roosevelt is the only New York dude that has got the making of a man in him.’ ”6 If Cody actually said such a thing, the compliment was decidedly double-edged. TR might possess the “making of a man,” but if so, it was only “the making.” He was still a New York dude.

There was a greater danger, too, in making the celebration of Roosevelt’s victory so central to the show. The charge up San Juan Hill marked the high-water mark of America’s overseas enthusiasm. Roosevelt’s victory was popular. But unlike George Custer, the only other military leader to become the subject of a Buffalo Bill’s Wild West scene, Roosevelt returned from his battles a living hero. He was also a political figure; he became governor of New York in 1898, then vice president to William McKinley in 1900, then president of the United States after McKinley’s assassination in 1901.

The Congress of Rough Riders threatened to become a political advertisement for the Rough Rider Republican. Cody had reasons for preferring Roosevelt to his Democratic rivals, as we shall see. Even so, many in his audience did not. Populists and many Democrats also favored American expansion, but they reviled the professional army and saw McKinley’s acquisition of the Philippines as a disaster. In 1900, Democrat William Jennings Bryan vigorously denounced McKinley’s imperialism for placing white American men in the steamy, sensual tropics, on a mudslide to miscegenation and the decline of the white race. He lost the election, but he still won over 45 percent of the popular vote. 7 Bryan had his supporters even then, and he remained a powerhouse in the Democratic Party for many years. For Cody, there was a very real possibility that the mythologizing of Roosevelt would disenchant a large part of the mass audience he needed to fill the bleachers.

The political limitations of the San Juan Hill reenactment help to explain why Cody shelved it about the time McKinley was killed and Roosevelt began swinging his big stick around the White House. In 1901, Cody replaced Roosevelt’s legendary charge with the “Battle of Tsien-Tsin,” a scene from China’s Boxer Rebellion in which “the allied armies of the world” rescued the besieged foreign legations and raised the triumphant “Banners of Civilization” in the place of the “Royal Standard of Paganism.”8

Various historians have argued that Cody’s freewheeling incorporation of recent events into his frontier narrative allowed him to tap popular sentiment for expansion. As the new century began, his show included “Strange People from Our New Possessions,” a group of “families” representing “the strange and interesting aboriginals”—Hawaiians, Filipinos, and Guamanians—from places “now grouped by the fate of war, the hand of progress and the conquering march of civilization under Old Glory’s protecting folds.” The new members of the show “keep step with the marvelous, potential and gigantic expansion of the nation.” 9 Some of these, notably the Hawaiian cowboys, or “paniolos,” even qualified as Rough Riders. By placing America’s expansion into its spectacle, Cody’s show implied a direct connection between frontier history and American victory on the world stage. By mingling cowboys and Indians with his professional military detachments, he incorporated symbols of amateur soldiers and volunteers, the kinds of military organization still preferred by a large segment of the populace.10

But close inspection of the show and its critics suggests these vague, ambiguous gestures to overseas expansion were politically risky for Cody. Westward expansion itself had been divisive, haunted by fears of racial decay, political disunion, and moral (and financial) bankruptcy. Ultimately, the economic success and overwhelming military victories of western annexation pushed those arguments into the mists of history, where they were easily forgotten. The Wild West show, for all its authentic western Indians, scouts, and cowboys, was by and large devoted to showing the settlement of the Far West that had already happened. The likelihood of any further military action against Indians was small when the show began in 1883, and grew smaller with each passing year. The Ghost Dance troubles erupted so suddenly, then receded into history so quickly, that Cody merely had to strike his usual ambivalent pose, urge the Nebraska state militia to remain calm, and wait for it to end. A popular sense that conquest of the Indians was inevitable limited other questions about the morality of that conquest.

The new expansion (as Roosevelt and his Republicans preferred to call it) or empire (as Bryan and the Democrats termed it) was either a glorious ascendance of democracy and capitalism or a turn from America’s virtuous, agrarian past into the halls of imperial corruption. This argument was rarely settled by a sense of inevitability. There were American victories in overseas battles. But underlying factors that facilitated American success in the Far West were largely absent outside North America. The demographic collapse of indigenous peoples through disease had been pivotal to American success in Kansas, Nebraska, and the entire continent, as it was in Hawaii. But disease would play much less of a role in subjugating indigenous people in the Philippines, where enduring connections to Asia ensured long exposure to Eurasian maladies and higher rates of native survival from epidemics.

Also, Europeans contested American power in Asia, Africa, and the Pacific in ways they seldom had in the post-1848 Far West. Isolationists and anti-imperialists could point over and over again to the cost of overseas deployments and the absence of compelling victories to urge the end to overseas adventures. American expansionists would have to articulate and rearticulate a convincing case for sacrificing lives and resources, because in no other way would American power be secured on distant shores.11

In some ways, the fear of racial degeneration and undemocratic consequences that flowed from governing imperial subjects loomed largest of all. A primary threat of continuing the Philippines occupation, according to many of its opponents, was the dissolution of soldiers’ marriages as they were tempted by polygamous native life. White women sickened in the Philippines, said press accounts. American men, debilitated by the malarial tropics and the temptations of naked primitives, were losing their manhood. Prone to violent excess, horrendous atrocities, and indolence, they were becoming more like the “weak and impotent” British who struggled against the Boers in South Africa, and more like the corrupted Spanish whom they had so recently expelled.12

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West had always presented Indian conquest in an ambivalent light. Perhaps having Indians play Spanish soldiers in the San Juan Hill reenactment, and Chinese soldiers in the “Battle of Tsien-Tsin” in 1901, was meant to complicate these historical moments, by infusing recent U.S. enemies with the honor of the noble savage.

If so, the gesture failed. The politics of empire were harder to contain in the past. The Indians masquerading as foreigners potentially rewrote the conquest of the American West as an imperial maneuver, upending the older narrative of inevitable, sometimes unfortunate progress across a unified continent. To many, the Chinese who fought the combined American, European, and Japanese forces in the Boxer Rebellion were not rebels, but brave patriots defending their native land. For these observers, Cody’s celebration of the Chinese defeat was more propaganda than entertainment. Mark Twain, the great fan of the original Wild West show, had become a major critic of America’s overseas engagements. The author who urged Cody to take the Wild West show to Europe in 1884 was less pleased when the show imported foreign entanglements into its drama. Twain was in the audience at Madison Square Garden on opening night, 1901. But he stormed out of the stands in protest at the jingoistic “Battle of Tsien-Tsin.”13

Cody himself had doubts about American expansion, especially the Spanish-American War. At the onset of hostilities, he offered to take up arms for the United States and to lend four hundred horses to the army for the campaign. Nelson Miles, now general of the army, appointed Cody to his staff. In April 1898, as the Wild West show began touring, Cody announced he would stay with the show until he was called to service. The 1898 show included a detachment of Cuban insurgents, the fighters for freedom on whose behalf the United States was ostensibly entering the conflict.

But Cody delayed joining. In his private correspondence, he suggested his doubts. “George, America is in for it,” he wrote an old friend, “and although my heart is not in this war—I must stand by America.” 14

Miles sent for Cody in late July. By that time, the Cuban campaign was already over, and the general was shipping out for what was to be a series of small, soon-forgotten battles in Puerto Rico. Still Cody could not bring himself to join. His business partners, especially Salsbury, were livid at the prospect of financial losses that would follow on the star’s departure and the early closing of the show. “Your bluff about going to Cuba was a brutal violation of your contract,” Salsbury later huffed, “and a moral wrong to the people who would have been thrown out of employment if you had been compelled to make your bluff good.”15 Cody wrote to his old friend Moses Kerngood, the man to whom he had sent Yellow Hair’s scalp in Rochester all those years ago, “I am all broke up because I can’t start tonight [for Puerto Rico].” It was impossible for him to leave without “some preparation, and it will entail a big loss and my partners naturally object. But go I must. I have been in every war our country has had since Bleeding Kansas war in which my father was killed. And I must be in this fight if I get in at the tail end!”16

But he did not. When Cody lamented that leaving the show would cost him $100,000, Miles advised him to stay.17

His reservations about the war stemmed more from his financial liability than from concerns about moral culpability. In that sense, his personal anxieties anticipated national sentiment after 1900. The American army in the Philippines turned from expelling the Spanish to fighting an indigenous rebellion. Combat and slaughter dragged on for years, costing the lives of 250,000 Filipinos and over 4,000 Americans. Even Roosevelt had turned against overseas acquisitions by 1901.18

Cody’s interest in reenacting overseas engagements waned almost at the same time. He ceased to present them after 1904, when he staged the Battle of San Juan Hill in Britain. The show retained generic displays of global warrior prowess with the Congress of Rough Riders and other exotic peoples, but connections to specific, foreign wars or battles disappeared. The colorful whirl of foreign and primitive peoples continued to reinforce the messages crafted in the early 1890s, about the capacity of white men to manage racially diverse primitives and modern technology sprung from frontier origins. “In its transportation, commissary, arenic, camp, and executive departments . . . the Wild West is at once a model and a wonder.”19

But even in its glamorous new format, for all its appeal to the press and the public, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show was anything but a guaranteed income. Cody was forty-eight years old in 1894, and the show’s Brooklyn summer at Ambrose Park cost him a fortune. “I am too worried just now to think of anything,” he wrote to his sister Julia. “This is the worst deal I ever had in my life—for my expenses are $4,000 a day, [a]nd I can’t reduce them, without closeing entirely. You can’t possibly appreciate my situation—this is the tightest squeeze of my life.” 20

Cody’s struggle to shore up the political relevance and profitability of the show accompanied his fading personal interest in performing it. Retirement was a form of vanishing, of fulfilling the frontiersman’s destiny, and hints of his permanent departure from the arena began to recur almost as often as the “Attack on the Settler’s Cabin.” He first hinted at retirement as early as 1877, when he announced he would leave the stage and spend the rest of his days on his ranch.21 Throughout the 1890s, he mused in public about leaving the Wild West show. For all the difficulties with Louisa, he still returned to Nebraska during every break from the road. He took long hunting and camping trips. As he aged, he seems to have been drawn ever more to home in the West.

The problem was how to find his rightful place there, as the old century gave way to the new. For a man who lived his life as a performance of the story of progress, the real challenge was in the denouement. He was acutely aware that how his life story ended would determine its meaning for the public. Commenting on how stories work, the philosopher David Carr observes that “only from the perspective of the end do the beginning and middle make sense.”22 If Cody’s life ended in the poorhouse, his biography would assume the dimensions of tragedy. If he ended it as a weary old showman, much of the authenticity of his early life, and of the frontier story, would be sacrificed. If he capped off his lifelong tale of frontier development with a triumphant culmination of real-life progress, he could validate the frontier myth he claimed as his own. From the mid-1890s on, William Cody dedicated himself to the search for an ending.

His efforts were of two kinds. On the one hand, Cody knew the manifold importance of entrepreneurialism as a real generator of wealth, as the commerce that expressed the maturity of civilization and its final stage of development, as evidence of the vitality and energy that characterized Anglo-Saxondom, and as proof of another great myth of America, the self-made man. To make a living in commerce required an entrepreneurial spirit and a willingness to tolerate setbacks. An estimated 95 percent of American businesses failed between 1873 and 1893.23 A wise man with money invested in a lot of different places.

Or so Cody seemed to think. His phenomenal energy spun off into dozens of different businesses after 1890. He invested heavily in theatrical productions, particularly in backing his lover, Katherine Clemmons. He bought bonds in a British short-line railroad in 1892. In 1893, he partnered with Frank “White Beaver” Powell to found the Cody-Powell Coffee Company, manufacturer and distributor of Panmalt Coffee. “Three pounds of Panmalt Coffee can be bought for the price of one pound of Java, and one pound of Panmalt is equal in strength and will go as far as a pound of Java, Mocha, or Rio.” He offered guiding services for tourist hunters out of Sheridan, Wyoming. For his sister Helen and her husband, Hugh Wetmore, and partly to advertise his other businesses, he bought a newspaper, the Duluth Press, and an office building in which to house it.24

The survival of American capitalism depended ever more on sales of consumer goods, and that entailed the expansion of sales, the sales pitch. Cody opened his show programs to advertisers. After 1893, audiences could read not only about Buffalo Bill’s lifelong adventures and the history of the show, but also pitches for Mennen’s Borated Talcum Powder, Sweet Orr & Co. Overalls Pants & Shirts, “The Best Union Made,” and Quaker Oats, “the Sunshine of the Breakfast Table—Accept No Substitutes.” There were ads for toys, for tools, for guns, for suspenders, and for bicycles. Cody himself endorsed more products personally: “I always use Winchester rifles and Winchester ammunition.” The John B. Stetson Company depicted “Buffalo Bill and his Stetson Hat.” Another enticed customers with the effectiveness of B. T. Babbitt’s Soap, “Used by this Show.”25 In their ongoing quest for markets to stave off overproduction and renew the economy, advertisers found in Buffalo Bill and his frontier originals at least a sheen of authenticity for manufactured goods, and Cody discovered a supplemental, if small, stream of cash.

But as he approached the end of his life, most of William Cody’s energy, and most of his cash, too, went into colonizing the great West. In a sense, creating community was a consistent project of his life. He was the son of a town founder, with an attempt at town founding in his own past, and the founder of the exemplary “little tented city” that sprang up in showgrounds on both sides of the Atlantic. The theory of civilization, with its advance from savagery to settlement, practically dictated that the culmination of his lifelong efforts should be a lasting town, with homes and families. With his large, but fluctuating, show profits he tried to make North Platte his own. He founded the town’s Buffalo Bill Hook and Ladder Company in 1889. In 1894, he bought expensive uniforms for the town band. (Each member’s flashy getup included a huge rosette, worn on the left breast, with Buffalo Bill’s face on it.)26 In partnership with his neighbor, Isaac Dillon, Cody ordered a ditch excavated from the North Platte River to his four-thousand-acre spread, then announced he would divide the property and colonize it with five hundred land-hungry Quakers from Philadelphia.27

Most of these projects, including the coffee company and the colonization plan, collapsed in the depression of 1893. Even if they had not, all the civic gifts in the world could not change the fact that North Platte would never bear his image the way he wanted. A patrician, even a philanthropist, he might be. But town founder, never. For the old scout to secure his legacy, and establish civilization in his wake, he would need to make a bolder move.

ACCORDING TO GEORGE BECK, who became Cody’s partner in the new town-founding project, Buffalo Bill came late to the game. Beck first scouted a new town site at the foot of Cedar Mountain, in Wyoming’s Big Horn Basin, sometime in the early 1890s. From the beginning, he planned to irrigate the land with water from the Stinking Water River, which flowed through it. Among those who accompanied him on his early expeditions was Elwood Mead, state engineer of Wyoming and a prominent irrigation expert, whom Beck had retained as a private consultant. It was an eventful trip. Beck and several of the party got lost and spent the night in the cabin of a lone settler. Mead and Beck surveyed the land and “ran a line of levels” at various places to determine the feasibility of irrigation. Soon after, Mead officially changed the river’s name from the Stinking Water to the Shoshone, to make the project more appealing to settlers.28

Accompanying Beck and Mead was Horton Boal, friend of Beck and husband of Arta Cody. As Beck remembered it, William Cody heard about the trip from Boal, and “came to me very anxious to get in” on the town-site plan. Beck and his partner, a Sheridan banker named H. C. Alger, “concluded to let Cody in for the reason that at the time he was probably the best advertised man in the world, and we thought that might be of some advantage.” They organized the Shoshone Irrigation Company, with Beck serving as secretary and manager, Alger as treasurer, and the world’s most famous frontiersman, Buffalo Bill himself, as its president.29

Beck chose “Shoshone” as the name of their first town, but the U.S. postmaster rejected it for being too similar to the existing address of Shoshone Agency, on the Shoshone Reservation, in the nearby Wind River Mountains. The partners submitted a new name, “Cody,” at William Cody’s insistence, and with Beck and the others persuaded that it could help advertise the settlement. (Had the postmaster rejected that name, they had designated another choice: Chicago.)30

Happy to be founding a town that bore his name, William Cody soon recruited more partners, especially showmen and magnates of print advertising. Nate Salsbury became a partner. At his suggestion, Cody approached George Bleistein, a Buffalo, New York, businessman who had made a fortune as a printer, particularly of posters for circuses and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. Along with two other entrepreneurs from New York, Bleistein contributed tens of thousands of dollars to the enterprise.

For all that, as far as we can tell Cody himself put the most cash into this effort. For the better part of a decade, a river of money ran from Buffalo Bill’s Wild West to the Big Horn Basin, scraping canals between river and settlers, building dams and headgates, erecting pumps, office buildings, stores, and liveries.

From the helm of a show about imperial glory, “The World’s Largest Arenic Exhibition,” Cody was thrilled with the imperial prospect of his town-building venture. The Big Horn Basin was “an empire of itself,” he wrote. Where Beck planned to found one town, Cody’s ambitions were much larger.31 He envisioned vast networks of irrigation ditches filled with sparkling water, lined with eager settlers who would spread it on verdant fields, and pump it into their thirsty towns, paying the Shoshone Irrigation Company for every drop. The West’s most famous irrigated town, Greeley, Colorado, “ain’t a potato patch” to the acres that Cody and his partners would make their own. “When one stops to think that all of Utah cultivates only 240,000 acres and the cities and towns there is in Utah—how many towns can we lay off and own on our 300,000 acres?” he asked a friend.

In 1897, Cody persuaded Salsbury to partner with him in an additional concern, claiming a vast 60,000-acre swath on the north side of the Shoshone River, opposite the Cody town site and extending many miles to the east. Across this entire area the two showmen hoped to establish farms and towns which would be served by a different canal, running along the north side, and which William Cody intended to build just as soon as the town of Cody was well under way.

For now, “the key note to all” was the roughly 28,000-acre spread on which the Shoshone Irrigation Company was building Cody town “at the forks of the Shoshone River,” where “the great sulphur springs which we own” would be a health resort and prime tourist attraction. It was “the greatest land deal ever,” and a fitting retirement, too. “We will all have a big farm of our own that will . . . support us in our old age and we can lay under the trees and swap lies.” 32 Culmination to Buffalo Bill’s long career as the great domesticator, the town would be a permanent tribute to the man whose show finished with a brief, climactic act of settlement. He would be wealthy, retired, and the revered founder of real civilization.

As Beck and the other partners had anticipated, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West proved a great advertisement. The securing of the settler’s cabin, which had long been the show climax, was now recapitulated with real-life domesticity for sale in the town of Cody, where audiences could find not only land, ranches, and farms, but also homes. “Irrigated Homes in the Big Horn Basin,” the “Greatest Agricultural Valley in the West, NOW OPEN to the Settler and Home-Seeker,” blared a full-page ad in the 1896 Wild West show program. “Homes in the Big Horn Basin” became the advertising refrain, and the following year, the pitch assured the crowds that these homes sat in bountiful fields. An arrangement of pumpkins, corn, and sheaves of wheat bore the label “Specimen of Products of Irrigated Lands— Cody Canal,” and another featured a wagon train trundling along a fulsome riverbank, with the caption “Cody Irrigation Canal, Big Horn Basin, Wy., 1897.”33

A program article explained that this was where Buffalo Bill himself recreated in the off-season, in a land that fended off the debilitating anxieties and neurasthenia of the cities. “The settler’s cabin and the stockman’s ranch houses and corrals” had replaced “the cone-shaped tepees” of an earlier time. “But the air that fills men’s lungs with health, their brains with noble thoughts, and their veins with new life, still remains.” The air was “so pure, so sweet and so bracing, that it intoxicates when poor, weak, cramped, damp, decayed, smoke-shrivelled lungs are distended by it.”34

Audiences in 1901 could find the same promises on the back cover of their show programs, as if Buffalo Bill’s settlement were where the show actually ended. “Shoshone Irrigation Company Owners of the Cody Canal Has Water Ready for Thousands of Acres of Good Lands.” Show spectators could read the official-looking endorsement letter from Elwood Mead, identified as the state engineer of Wyoming (and carefully not identified as paid consultant to the company): “I know of no place in this country which offers to prudent and industrious farmers greater assurances of material prosperity and physical comfort than the Big Horn Basin.” The country was “equally well adapted to the purposes of the stock raiser, grain grower, fruit raiser, or market gardener.” Mead told the crowds from Bay City, Michigan, to Opelika, Alabama, that “the Cody Canal takes its water supply from one of the largest rivers in the West, and reclaims some of the best land in the State. The completed portion is well and substantially built with an ample capacity to water all the land below it.”35

Of course, advertising went beyond show programs. Even before any settlers arrived, Cody himself had established the town’s first newspaper, the Shoshone News (with John Burke as temporary editor), to advertise the basin’s potential. By 1899 he had imported a new editor, J. H. Peake, to run the new paper, the Cody Enterprise. In the Enterprise, and in his Minnesota paper, the Duluth Press, he took out large ads, promising land and water, with a drawing of Buffalo Bill welcoming readers to a verdant mountain valley, where they could find “Titles to Homes Perfect.”36 Cody spoke often of the town in interviews with overseas newspapers. “I am making canals for irrigation purposes, opening mines, and acting as agent for the Government in granting concessions to prospective settlers,” he told an English reporter in 1903. 37

Indeed, the town became the new center of William Cody’s continuing, almost manic entrepreneurialism. In addition to newspapers, he founded a livery stable, began gold mines and coal mines, and drilled oil wells. In 1902, he opened the elegant Irma Hotel, named for his youngest daughter, with a remarkable collection of western paintings and fine furnishings in a granite building whose design and construction (at a reputed cost of $80,000) he supervised closely. “I am very anxious of getting the concession of putting on an automobile and horse stage line from Cody into the Yellowstone Park,” he wrote the state’s governor in 1903.38 Not satisfied with a stage line, he built two hotels along the route.39

Many of his efforts failed. Gold, coal, and oil deposits were rapidly exhausted or proved so minute as to be not worth extracting. Nevertheless, as these businesses and the settlement progressed, they, and especially the town itself, increasingly became subjects of the Wild West show. The Burlington & Missouri River Railroad reached the town in 1901. Beginning about this time, a coterie of Cody residents (or people who claimed to be Cody residents) carried a banner, “Cody Delegation of Boosters from Buffalo Bill’s Home Town,” in the show parade and in the grand entrance into the arena. When the emigrant wagon train trundled before the stands, their canvases read “Take the Burlington Route to the Big Horn Basin,” as if to suggest that spectators did not need to endure an Indian attack to participate in the continuing settlement and domestication of the frontier.40 The ads for the irrigated tracts awaiting the “homeseeker” pointed the way out of the arena and the city. Spectators longing to escape urban threats or their declining prospects in eastern and midwestern farms heard a consistent message: take the train to Cody town, and home.

As the nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth, shifting cultural currents made the “Attack on the Settler’s Cabin” and these promises of real western homes ever more resonant for show audiences, and the role of real-life “home builder” even more attractive to William Cody. Public anxieties about the survival of the home and family, and public veneration of home builders, today’s “developers,” grew more pronounced as the frontier closed, as urbanization maintained its rapid pace, and as depression made Americans painfully aware of the uncertainties of the new industrial economy. The home continued to be the bedrock of American civilization, and those who built them were great citizens indeed. As one commentator put it, “Home building is the best business in the world. The home is the seat of the happiness and the sheet anchor of free government. In the family fireside is planted deep the flag of this republic. Those who broaden the domain of homes are the true patriots and our greatest men.” 41

With their bucolic advertisements and their remote western location, the homes for sale in the Big Horn Basin were decidedly “country homes,” the most desirable of all homes. In the popular imagination, country homes included the more elegant city suburbs. They were not necessarily farms. Rather, they were situated somewhat ambiguously in what scholar Leo Marx has called a “middle landscape” between remote hinterland and decadent city. They fused modern technology of the city—ready water, electricity, and telephones—with rural virtue. The country home was, in the words of one anxious proponent, “the safe anchored foundation of the Republic,” the “fountain-head of purity and strength,” which “will nourish and sustain this nation forever.”42 As the cities erupted in polyglot confusion, the destiny of the white middle class could be secured in these rustic dwellings, nestled in an agrarian empire surrounding the cities, at once supporting them with their produce, and containing them with their virtue.43

Advertising for Cody’s country home empire masked the hard road ahead for the Shoshone Irrigation Company and the town’s early settlers. By 1895, when the company began work in earnest, the West’s most arable and desirable land had long since been taken. The swath of Big Horn Basin claimed by the partners was not a blank slate or a showgrounds on which settlement could be projected. It was a real place, with real nature, and that nature did not go easy on pastoral dreams.

Travelers to the company’s town site, especially before the railroad reached the town in 1901, had to struggle first with its remoteness. The Big Horn Basin lay behind the formidable Wind River Mountains to the south and the Big Horn range to the east, with the high country of the Continental Divide to the west. Red Lodge, the nearest settlement where supplies could be had, was an arduous two-day wagon ride north, in Montana. (Early surveyors recommended that the region be attached to the state of Montana rather than Wyoming.)44 Even after the Burlington & Missouri completed its 120-mile spur line from Toluca, Montana, to Cody, the ride from Chicago or other points east was long and tiresome.45

Reaching the area was nowhere near as difficult as farming it, however. The Big Horn Basin was a sandy sagebrush flat. The center of it was the driest area in Wyoming, garnering less than six inches of rain per year. An early government surveyor, who saw the basin fifteen years before Beck did, concluded that it appeared “very desolate, except along the valleys” of the Big Horn River tributaries. From the basin’s western side, where the company laid out its town site, these tributaries, including the Shoshone River, flowed east into the Big Horn River. The larger river flowed north out of the basin’s belly, joined by the Little Big Horn River in Montana and finally pouring into the Missouri River over a hundred miles away. 46

The Shoshone River was sizable, and like other streams and rivers noted by that early surveyor it was fringed “with cotton-woods and narrow, grassy bottoms.” But the water was sulfurous (thus its early name, the Stinking Water), and even this rather pungent riparian oasis was eroded deep into the valley floor. The unwillingness of water to run uphill made simple irrigation ditches inadequate for watering the sagebrush-covered benches that jutted up hundreds of feet from the riverbanks and made up most of the basin’s real estate. To bring water to the town site, partners had to contract for a canal that began miles upriver and tracked around a mountain to the lower flats where the town was located.

Finally, even if a steady supply of water could be secured, the climate provided other obstacles. The altitude, four thousand feet, meant early frosts and late snows. Basin winters were not the coldest in Wyoming, but with extremes of thirty degrees below zero, they were cold enough to dissuade most farmers. In the summer, on the other hand, the Big Horn Basin was often the hottest place in all of Wyoming. Winter and summer alike, as the sun warmed the basin floor, heated air rose upward, drawing cold air out of the highlands to the west. A cooling draft can lighten the burden of summer heat, but emigrants were rocked by these unpredictable gusts, which reached sixty miles per hour. Most early visitors found the basin bleak. An early encampment of miners had ventured to the Big Horn Basin in 1870, but they soon departed. In 1895, other than a few cowboys and ranchers on open-range cattle outfits, almost nobody resided in the basin permanently.

The challenges to settling this place with middle-class homeowners were huge. In 1895, George Beck drew up a map to aid him in the work of laying out the first town site. One day, he put the map down, weighted it with a rock, and walked over to talk with his engineer, C. E. Hayden, who was working a few hundred yards away. While they spoke, “a summer whirl wind came along and picked the map up and started it heavenward,” Beck later recalled. “Hayden and I followed it as far as we could but it kept going and we concluded our map was recorded in Abraham’s bosom.”47

So the environment of the Big Horn Basin threatened to carry away the tidy visions of town planners. Cody himself would expend vast effort, and a vast fortune, to hold the ordered grids of his towns against the basin’s uncooperative nature. As much as it fired him in its early days, and as often as he touted its glories in show programs and press interviews, the project posed a fierce challenge to his business acumen, testing his sense of personal and national destiny. Indeed, only a major shift in government policy toward the arid West would guarantee the settlement’s success. In doing so, it relieved William Cody of his town site’s burdens. But it also stripped his dreams away.

THE TOWN BUSINESS required extensive advertising, and not a little deception. Thus, in 1896, Cody and Beck fought hard to make their new town, which was little more than a land office, the county seat of the new Big Horn County. Success would guarantee the town a county courthouse and the aura of permanence. After that, both investor capital and settlers would be easier to recruit.

But the designation of county seat was made in an election by county voters, most of whom lived nearer to existing settlements which they favored for the seat. The company’s only hope of winning the election was to continue paying work crews who were digging the irrigation ditches and hope this persuaded voters that Cody was a real town, and not another booster fantasy. If the excavation stopped, word would spread quickly that the town was failing and the election would be lost. The problem was, the partners were out of cash to pay the workers, who numbered over a hundred, or to feed the teams of horses that drew the scrapers.48 So they launched an effort to sell corporate bonds, guaranteed with their personal property, to raise the money they needed.49

The bond sales failed, however, because eastern investors were suddenly leery of western investments. Their nervousness grew with the expanding popularity of William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic candidate for the presidency, and his Populist allies, who had threatened to repudiate bonds and mortgages if they were elected. Until financiers were certain he would not be president, no eastern money could be had. Meanwhile, the Shoshone Irrigation Company remained thirsty for cash, for laborers, and for equipment. “I have had the worst time in my life standing off people as I have been told to go slow and I have written letters of excuse for not paying accounts till I do not know what to say to them any longer,” wrote George Beck. “Any man we owe a penny to has written in all kinds of English and they all seem to want payment.”50

The sober solution would have been to shut down operations in the Big Horn Basin until money could be raised. But doing so would have signified the town’s prospects were illusory, thereby conceding the county seat fight, and passing up a potential boost to confidence in the town’s future among investors, settlers, and the public generally.

The county seat fight was only one of many similar episodes in the early life of the town of Cody. Successful town founding required promoters to deceive much of the public much of the time. The similarities between show business and town business were not lost on the principals. As Beck told Cody, “If we can keep up a show for thirty days now we have a fine chance to make a very good thing.”51 Ultimately, Cody and Salsbury managed to sell an indemnity bond to Phoebe Hearst, wife of California senator and Comstock Lode magnate George Hearst, who advanced them $30,000 on terms of repayment in five years at 7.5 percent.52 But even so, the county seat fight was lost to nearby Basin.53 Town founding was an ongoing gamble, in which Cody, Beck, Salsbury, and the other partners wagered heavy sums and much effort on a town that might in the end prove to be more show than substance.

The baleful influence of the Populists on western capital influenced other aspects of Cody’s personal finances. In most years, he borrowed money for his show and other businesses, securing loans with mortgages on his Nebraska property. He then paid the mortgages off with show receipts. By 1896, this was proving more difficult, he explained to a friend, because “the damn populists have repudiated so many loans that eastern capital fight shy of Nebraska and Kansas particularly.” (Thus, when Beck finally acquired the bond money from Phoebe Hearst, he promptly lent Cody and Salsbury $5,000 of it to open the Wild West show that year.)54

William Cody’s struggle to raise bond money for his ditches amid the Populist insurgency suggests how much western environment and economics had combined to make the New West something less than the pastoral paradise of agrarian myth or of Wild West show programs. The need for irrigation itself reflected the absence of rain, the single most unifying environmental characteristic of the Great Plains and the interior of the West. Plains farmers had responded to aridity by planting dryland crops, especially wheat and corn, across millions of acres churned up by their plows. The result was a glut of wheat and corn, and steadily declining produce prices. At the same time, farmers bought new technology, on credit, seeding more acres against their declining incomes. Land under the plow more than doubled, and farmers cultivated more land in the last third of the nineteenth century than they had in all the prior history of the republic.55

The result was even more overproduction, still lower farm profits, and more unpaid debts. By the early 1890s, wheat was more expensive to raise than it was to buy. Almost half of Kansas farmers were in default on their mortgages. In Nebraska, the brutal droughts of 1893 and ’94 drove already reeling settlers to despair.56

Just as the European encounter with the wilderness inspired both the frontier dream and the gothic nightmare, so the American encounter with the arid Far West inspired both Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, a dramatic depiction of westward expansion as the route to hardy independence, and Populism, a radical politics to recapture independence lost to the very railroads and markets which had made westward expansion (and the Wild West show) possible. The ironies and contradictions of these competing western myths and realities were exemplified in the history of Nebraska, the state that produced both William Cody and William Jennings Bryan. The “Boy Orator of the Platte,” Bryan was elected to Congress for the first time in November of 1890 (just as Cody was about to attempt Sitting Bull’s arrest). The congressman soon became the leading exponent of “free silver,” a catchphrase for abandoning the gold standard in order to increase money in circulation and thus to inflate those depressed crop prices which so plagued western farmers.

Corporate interests saw Bryan as a western radical, almost a trans-Mississippi monster, who threatened the very integrity of the financial system. 57 Nate Salsbury, creditor and part owner of a corporate, railroad-dependent amusement and now busily hawking bonds against a real estate speculation, shared that opinion. “The money market is closed to all kinds of investments and will stay so as long as that blatherskite Bryan is rampaging around the country,” he fumed.58 At times, he considered Bryan a rival western showman who threatened ruin. “I am happy to say,” he reported after Bryan’s 1896 campaign swing through New York, “that he made the most distinguished failure at Madison Square Garden the other night. . . . He came to paralyze New York and got a body blow that took the wind out of him and [his] ass-toot managers, and they have retired to the boundless prairies to rub themselves down with buffalo chip and get some more wind.”59

Cody remained more ambivalent than Salsbury in his politics. He was not without sympathy for the Populists, and for Bryan in particular. In 1896, the town of North Platte hosted a state irrigation fair, and the organizing committee cast about for an eminent speaker to open the event. Cody recommended Bryan. He had reservations about the free silver campaign—“I don’t like some of the party’s moves,” he told one correspondent—but Bryan was still his candidate, and he was certain he would one day be president. Had Bryan become president, Cody would likely have been at his inauguration. As it turned out, Bryan lost—and Buffalo Bill attended McKinley’s inauguration instead.60

Cody town’s appeal lay in its possibilities for escape not merely from the city, but also from the crisis of the farm. The irrigated fields of Cody town ideally would grow specialty crops, fruit and nuts in particular, and allow residents to escape the price deflation and drought that plagued dryland farmers of wheat and corn.

Indeed, William Cody’s effort to found irrigated towns was only one of many similar efforts across the West, where an emerging movement saw in irrigation the chance to redeem the West not from savage Indians, who were no longer a threat, but from increasingly dangerous political trends. For all Nate Salsbury’s pique, Populism and free silver were politically moderate compared to other forms of radicalism that swept the West after 1890. Western economics were notoriously unstable. With only a tiny manufacturing sector, the region’s jobs were mostly in extractive industries, and wage workers like miners, lumberjacks, farmhands, and ranch cowboys were even more vulnerable than eastern workers to commodity price deflation (a condition which stoked their enthusiasm for the potentially insurrectionist industrial armies in 1894).

Thus, a new union, the Western Federation of Miners, was born in the depression of 1893. Over the next fifteen years, miners and mine owners were locked in bitter, sometimes violent strikes. In 1905, federation members led the charge to create a new, even more radical union, the Industrial Workers of the World. The IWW was a nationwide organization, but its socialist appeal for “One Big Union” was strongest in the West.

Other examples of the furious radicalism of the postfrontier West abound. Socialists grew stronger in many states as Democrats and Republicans failed to ameliorate industrial working conditions, and the state with the largest proportion of Socialist voters was Oklahoma. After the Russian Revolution of 1917, the most hallowed tomb of Communists was the Kremlin wall, which holds the remains of only two Americans. One of them, journalist John Reed, was from Oregon. The other, unionist Bill Haywood, was from Utah.61 For many thinkers and policymakers, the West’s tumultuous, chaotic politics made the country homes of Cody town and other irrigation projects ever more appealing, even necessary, as warm hearths of middle-class sensibility and democracy in a wilderness of political unrest.

But the key to those homes was irrigation. Frontier myth had always promised a path between ideologies of left and right, between wealth redistribution and aristocratic hierarchy. But in the postfrontier West, the old narrative of progress and civilization sprung from the frontier seemed more and more like a poetic fiction which offered no real alternatives. Ranching was supposed to be a precursor to farming, but farms failed in the cold, dry climate of the high Plains, making the region resistant to settlement. In 1900, Wyoming’s population had yet to reach 93,000. A state for eleven years, it had attracted slightly more than a tenth of one percent of the seventy-five million people who inhabited the United States. Only Nevada had fewer residents.62 Indeed, ranching was not only durable but, organized along new corporate lines, it became a barrier to the advance of the domesticity and civilization of the farm. In the 1880s and 1890s, meatpackers from Chicago and other large investors consolidated control of the western range, squeezing out smallholders and homesteaders, who depended on public lands to graze their animals, by enclosing streams and rivers with barbed wire.

The resultant range wars resulted in bloodshed and a great deal of rustling; the most spectacular episode occurred in Wyoming in 1892. East of the Big Horns, in Johnson County, large ranchers with ties to railroad corporations hired a gang of Texas gunmen to assassinate smallholders, many of them homesteaders or small, independent cattle outfits, near the town of Buffalo. The mercenaries descended first on the cabin of Nate Champion, a cowboy who sided with the smallholders. But Champion fought them off all day before perishing in a hail of bullets. Johnson County’s sheriff and his posse soon cornered the invading Texans, but large ranchers prevailed on the governor to request federal troops. The army escorted the hired guns to jail. Through intimidation of witnesses and judicial corruption, all of the accused killers and the ranchers who hired them were released.

Each side in Johnson County told a story, and insofar as those stories revealed much larger political and social perspectives, to choose sides was to select one narrative over another. To large ranchers and their allies, smallholders were rustlers, criminals, and vagrants who had to be stopped. To smallholders, large ranchers were greedy corporate monopolists who quashed the common man’s dream.

But whatever story one believed, Johnson County’s bloodshed underscored the continuing predominance of undomesticated ranching over family farming. 63 Despite modern nostalgia for family-centered ranches, nineteenth-century Americans were suspicious of ranching. Unlike farming, which was bound firmly to family in the popular mind, ranching was renowned for being excessively male, and for not constituting families.64 Ranching required extensive resource use—dispersed grazing—rather than intensive cultivation. Ranching did not turn the wilderness to garden; it did not complete the ascent of civilization. Many ranchers did not even build permanent homes. In Johnson County and across Wyoming, even large ranch owners with families tended to live in cities. They sought control of the range as a pasture, but not as a home for themselves.65 So the range was populated mostly by ranch hands, or cowboys. Even in 1900, the 93,000 residents of Wyoming included fewer than 35,000 females.66

Among locals, the absence of women signified the absence of families, and of domestic order. Family was the key to social regeneration, the purpose of settlement, and still the most durable rural institution.67 Rather than the settler’s cabin, with its wife and children, Johnson County called to mind an army of gunmen (or deputies) arrayed around a cowboys’ (or rustlers’) cabin, with bullets flying thick between the principals. Whatever else it was, the Johnson County war resonated with hypermasculine frenzy. Domesticity was nowhere on the horizon. Progress had stopped. If the story of the Far West was supposed to be one of progress from ranch and range to farm and civilization, then Wyoming was in the grip of plot failure.

Ideally, the founding of Cody offered a means out of the narrative impasse by providing an improved nature for family farms. Indeed, Johnson County was on the mind of at least one town founder. In 1892, George Beck himself owned a ranch not far from Buffalo, as well as business interests in the town, including a flour mill, an electric light plant, and a waterworks. He later claimed that ranchers invited him to join their invasion, but that he refused and warned them it would “end in disaster.”68 At the same time, he had little time for smallholders either, most of whom he considered thieves. Like most Americans, Beck became convinced that partisans in the class wars of the Gilded Age were zealots, be they ranchers and homesteaders in Wyoming or workers and owners in Chicago. What the nation needed was for both sides to show restraint (or be restrained) until the failing abundance of the frontier could be refreshed through an application of science, technology, and capital—of the kind Beck and Cody brought to the Big Horn Basin.

In this sense, William Cody and his partners in the Shoshone Irrigation Company were part of a much broader movement of professional engineers, capitalists, and reformers who saw in irrigation a trail that wound safely past savage ranchers, Populist demagogues, and menacing leftists to the bucolic country home. Visions of profuse fields along the Cody Canal hearkened to some of the oldest reform traditions in America. Since the beginning of the republic, writers and politicians from Thomas Jefferson to Horace Greeley had lobbied the federal government to remove Indians, build roads and railroads, and restrain land speculators, all to open a “safety valve” on the frontier for American workers trapped in decadent cities.

The term “safety valve” was adopted from a feature of industrial boilers, a fact which suggests how much the theory reflected urban ideas rather than western reality. In fact, the West was never a safety valve. Farm making was too expensive for most urban workers, and few in the cities had any knowledge of farming. But the idea that the West had served as an escape hatch for the downwardly mobile, a bulwark against class conflict, remained conventional wisdom throughout the nineteenth century. Around 1890, as the frontier closed, reformers began looking for ways to expand the supply of arable land to keep open, or reopen, the safety valve. The day of the irrigator had arrived.69

Irrigation promised an end to western aridity and its attendant savagery, and a new start on homemaking along the remnant frontier. Irrigation engineers, water lawyers, utopian idealists, and others banded together in national associations, created national magazines, such as The Irrigation Age, and held national conventions. They designed legislation to irrigate the vast western desert. Their most famous advocate was William Ellsworth Smythe (who—like Cody and Bryan—was from Nebraska). Smythe’s 1899 book, The Conquest of Arid America, promoted irrigation of the arid West as a means of securing a millennial future: farms and work for the teeming unemployed masses; better health in the dry air; more wholesome, democratic communities (a result of having to work together to dig and maintain canals); national greatness (all the great civilizations of the ancient world had been irrigated desert kingdoms). If these were not reasons enough, Smythe and his allies spoke fervently of “reclaiming the desert,” infusing their campaigns with biblical language and the aura of the sacred. Irrigation became, in Smythe’s prediction, the culmination of world history, the rise of the American people to a new level of wealth and power which would collapse age-old distinctions—between city and country, East and West, producer and worker, rich and poor—which threatened to tear the country apart as the new century dawned. His was a peaceful answer to Populists, anarchists, socialists, monopolist ranchers, rustlers, and all the other radicals who threatened the progressive march of civilization. 70

Few could argue with these green dreams. The problem was how to make them come true. Digging ditches was so backbreaking and tedious that few could afford to pay the laborers. The cost of irrigation canals was far more than any smallholder could afford. To provide incentives for capitalists, in 1894 Wyoming politicians secured passage of a landmark irrigation bill, the Carey Act (named for Wyoming senator Joseph Carey).

The Carey Act provided the legal framework for the development of the Cody Canal and the town of Cody. The law stipulated that any private developer who showed he had means and a plan to provide a water supply for an unclaimed desert acreage could file for the right to develop it. Because unclaimed lands in the West remained in federal hands until they passed into private ownership, federal officials had to review the plan. Once they were satisfied of its soundness, they would separate or, in the parlance of the law, “segregate” the acreage from federal holdings. The segregation was then handed over to the state. When settlers arrived, they paid the state fifty cents an acre for up to 160 acres of land.

For his part, the private developer made money by investing in an irrigation system and selling permanent water rights to the same settlers for up to $15 per acre. Once the water rights were sold, the settlers assumed ownership of the ditch and the irrigation system, which they maintained. The capitalist who financed the development could then retire, rich and happy. 71 At least, that was the idea.

As much as it appealed to William Cody, to his partners, and to Wyoming’s political leadership, the law proved such a poor vehicle for settling the Big Horn Basin and other places that Congress drafted succeeding legislation within a decade. The overwhelming fact which the Shoshone partners could never overcome was the expense of irrigation works. The Cody Canal was no small ditch. Four feet deep, twenty-one feet wide at the bottom, and broadening to thirty feet at the top, the completed canal would run over twelve miles from headgate to townsite. There, it would branch into more than fifty miles of lateral channels (which the company also had to excavate), spreading water over almost 20,000 acres. Early estimates of construction costs ran to $200,000.72 In the end, the Cody Canal cost much more, and it took years to finish (even after Elwood Mead and others pronounced it “substantially complete”). Workers were hard to find, and excavation ceased completely when the ground froze in the long, often subzero winters. In 1897, water trickled into the canal from the Shoshone River and began rushing toward the settlement, a promising moment indeed. But when the water was within a mile and a half of the townsite, the bank blew out, and the water poured into the breach, forcing closure of the canal until the leak was fixed. Cold weather prevented repairs until the following year. Even then, engineers were flummoxed by the high gypsum content of the soil, which made it especially porous, leading to more washouts which they tried to rectify by working straw and hay into the ground. For years afterward, the washout would plague canal operators.73

Even when the canal operated, the water froze in winter, and settlers went back to hauling water from the river again. Delays like this were mortal to the interests of investors, who were hoping for a return on their outlays within a few years but who watched as years passed and ditch construction took ever more of their capital.

Settlers were the key to profits, of course. But obstacles prevented the town from becoming a popular emigrant destination. The remoteness of the Big Horn Basin, especially before the railroad was complete, meant that farmers in the basin had no ready market for crops. Water rights were expensive. In the beginning, the company sold them for $10 per acre. Even a forty-acre farm would cost $400 for water rights, plus $20 for the land—a year’s wages for the average American laborer.74 Although the price was payable over five years, the costs of farm making in Cody remained substantial. A 160-acre farm cost nearly $2,000 before interest. And, for those who dared to stake their farm on the Cody Canal, an entire year would pass before a crop matured. Ideally the town could provide a business nexus for service industries. But few craftsmen could support themselves without the elusive settlers. Because it required heavy cash investment up front, Cody town was no safety valve.

In 1896, the Shoshone Irrigation Company contracted with emigration agents (businessmen who took a commission from town builders for recruiting emigrants to settle on their lands). They succeeded in bringing a group of seven families from Illinois to begin the new town. By the end of the summer, only one of these families remained, the rest having been intimidated by the bleak setting, the poor prospects for the canal’s completion, and local ranchers whose cattle ravaged their gardens and whose cowboys maligned and frightened them.75

The Shoshone Irrigation Company hired a staff member of their own, D. H. Elliott, to recruit more emigrants. He spent months corresponding with the Swedish Association and other emigrant mutual aid societies, trying to entice immigrants to the town site. Touting the advantages of reclaimed desert as a tonic for the ailments of industrialism, he even approached the famous socialist, Eugene Debs. The leader of the Social Democratic Party had announced a “Social Democracy Colonization scheme,” a model community where the unemployed could work the land while they waited for jobs. Elliott depicted Big Horn County as the socialists’ promised land. “The Big Horn is a new county, very evenly divided, as is also the State of Wyoming, politically, hence, with a very few colonists they could have the balance of power, politically, if they so desired.” Cody approved the idea. Shoshone Irrigation Company partners were so desperate to settle the town that even the virulently antiradical Salsbury endorsed it.76

But the Social Democrats decided a socialist Wyoming was not in the cards, and ignored the invitation. The company went back to recruiting more conventional settlers. By the end of 1897, the partners had fired Elliott to cut expenses.77

To say settlers were slow in coming is not to say there was no interest. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West broadcast the opportunities of Cody far and wide. Out in Wyoming, George Beck was inundated with letters from prospective settlers. Howard Martin of Monmouth, Illinois, wrote as “a prospective homeseaker of the far wist,” requesting information about “inducements that your Co. has to offer or any and all information pertaining to the country its people climate and if the well water is any part of it alcoli [sic].” C. M. Stewart of Brattleboro, Vermont, wanted to know “if we can take homesteds now,” under the Carey Act, “that will be watered by your canal.” C. L. Goodwin of Sutton Creek, Pennsylvania, requested “all the information a homeseeker would wish to know,” regarding “lands you have for sale . . . water rights, least number of acres you sell . . . What is the least number of acres a man can farm of irrigated canal in Wyoming and make a living.”78 If the stacks of letters that arrived in the Big Horn Basin are any indication, would-be settlers seemed to come mostly from other rural areas and small towns. Few wrote from cities. Most knew a thing or two about farming. They asked how soon the frost came, how long the snow lasted, how high the elevation was. Many who were not farmers asked if they could find work making bricks, operating a creamery, or practicing law. Hundreds wrote. Few came.

The town site’s remoteness and the reluctance of settlers made company partners as vulnerable to the whims of railroad bosses as any other town founders in the West. Not long before his death, William Cody alleged that he had persuaded the Burlington & Missouri River Railroad to build a line south from Montana, and “if it had not been for me there would not be a mile of railroad in the Big Horn Basin today.”79 In fact, the Burlington & Missouri began planning a transcontinental route past Yellowstone National Park early in the 1890s. The eastern approach to the park, along the Shoshone River, was a likely route. Company representatives toured with Beck and Cody along the river as early as 1895, and there were rumors in the press that the B&M—not Buffalo Bill—would build the town that year.80

But, in typical railway fashion, the railroad let others bear the expense of building the town, then extorted their cut. Once the town site was under way, B&M officials announced they would build a spur line to Cody from Toluca, Montana. Cody knew railroads, and the approach of the B&M was both a heartening sign and an uncomfortable reminder of his losses to the Kansas Pacific at his town of Rome in 1867. He wrote to Beck: “Did it ever strike you that we have got to keep our eyes peeled or the B&M might make Cody howl like the K & P made my town of Rome howl?” During a trip to Omaha, the general manager of the railroad, George Holdredge, “said he wanted to talk with me when I got their this fall, but he did not say what about.” Cody was certain they wanted town land. “RR are out for the stuff— and I know from experience what they can do. Are we going to be prepared to act liberally with them? For it’s going to come to a showdown pretty soon.”81

He was right. Soon after their tracks began extending up the Shoshone River, the B&M let it be known that the line would stop miles short of Cody town—unless the Shoshone Irrigation Company handed over half the town lots. William Cody and his partners obliged.82 That November, the railroad arrived—although there was no railroad bridge across the river, and travelers had to walk or find other transport the last mile and a half of the journey.

The completion of the rail line consummated the town founding. Shortly before the first train steamed into Cody, the town incorporated, with a population of 550 (the count was probably inflated).83 Six years after he began his efforts, Cody’s namesake town remained smaller than Buffalo Bill’s Wild West traveling camp. Even with the railroad, it was still less well developed than the Wild West show, too. The Shoshone Irrigation Company had promised a town waterworks. But two years after the railroad spur opened, residents were still paying a door-to-door delivery service twentyfive cents a barrel for their water.84 By 1905, of the 25,000 acres segregated for settlement along the Cody Canal, only 6,500 acres were actually irrigated. In 1907, officials finally judged the Cody Canal satisfactory, allowing the Shoshone Irrigation Company to cede responsibility for the canal to the community. But the list of unhappy settlers was long. By 1910, the litany of canal washouts, flooded fields, and other broken promises left the Shoshone Irrigation Company with a checkered past. Cody and his partners had been sued at least twenty-six times.85

The settlers of Cody were overwhelmingly middle class, and they expressed their aspirations to gentility with literary societies, church socials, and, beginning in 1901, meetings of the Cody Club, a gentleman’s organization that served as the de facto chamber of commerce.86 William Cody himself wore a white coat and tails to the grand opening of the Irma Hotel in 1902. “Most of the gentlemen were in evening dress, and a great many handsome and costly toilets were worn by the ladies present,” wrote a local journalist.87

But a glimpse of the town even years later suggests that for many, such gestures only padded the settlement’s rough edges. Nana Haight, a New Yorker and the wife of a pastor, arrived in Cody in 1910. She grew to like many things about her neighbors and the community, but on her arrival she could not hide her disappointment.

It has only 1000 inhabitants and is fully two miles away from the railroad station; hardly a tree and mostly one story buildings, wooden sidewalks, and a few lights at night. My heart sank when the bus brought us down across a swiftly running river, up a steep hill to the town. . . . Such winds as we have. The children pass our house going to school and go along backing up slowly against the wind. However, they blow home quickly. . . . There is one block with shops on one side and ten saloons on the other. Only two stores that seem to keep everything: paint, drygoods, groceries, and all kinds of goods for hunting. Two butcher shops with terrible meat, tough as shoe leather. Also, a drugstore and two banks, and a few odd stationery, candy, and cigar stores. The tailor is on the other side of the street amidst the saloons, so I have to brave it if I go there. No one ever knows when some man will be suddenly thrown out on the street from one of the saloons. 88

The spare, undomesticated appearance of the settlement notwithstanding, William Cody’s venture in the Big Horn Basin became the focus of his efforts like nothing else since the creation of the Wild West show. To say Cody himself took a strong personal interest in the affairs of the town is a considerable understatement. He became its primary advocate and patrician. After 1901, he began spending each winter at his new ranch, the TE (a brand he bought from friend Mike Russell), on the remote reaches of the South Fork of the Shoshone River, where he built a small house with a white picket fence. From there he soldiered through snow to reassure settlers. Residents remembered that he would “call on families who had established homes along the canal. He always had words of encouragement and complimented them on the splendid homes they had started and improvements they had made.” Other times, residents met him driving his buggy along the road. He “would stop to visit with all whom he met, asking how they were getting along and the type of ranching or farming they were doing.” Some recalled that his free-spending visits provided the settlement’s major source of cash. 89

He spent most of each year on the road with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. But to judge by his behavior, he saw the town as another show in need of his hands-on direction. Unable to distinguish tasks he should delegate from duties he could not, he wrote hundreds of letters criticizing almost everything about Beck’s operation in the town. He complained about heavy expenses and the lack of news from Beck. He insisted on knowing how much money was paid to the company and how it was spent. “This is discouraging,” he wrote upon hearing that a new mail route would bypass the town. “Had I been informed of a proposal of this kind I think I could have brought influence to bear.” He was full of suggestions—and demands—about the kinds of buildings in the town. “Of course we must have an office building. And while about it, it ought to be big enough to serve as a hotel this winter.” 90 And he was especially bitter over the many ditch failures. “It was neglect and carelessness that the water should be allowed to wash out the new canal,” he lectured Beck in 1898.91

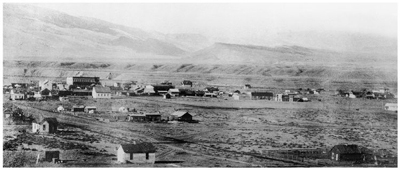

Cody, Wyoming, c. 1905. Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

Such close attention was typical of Cody’s business manner. But if it brought him success in show business, it did him little good in the town business. His show made profits, albeit unevenly. The town did not. “I am doing my best to raise money,” he wrote Beck. “I tell you it keeps me sweating blood but no use getting discouraged. [I]f you can only protect our name and credit, I will say thank God.”92 Failure to complete the canal in a timely fashion could be disastrous. Officials “will make an unfavorable report of our canal if something substancial is not done,” he warned Beck.93 The result of cumulative poor assessments would be the loss of their segregation, and their investment.

Despite the town’s halting development, Cody hoped it would yet provide him means to retire from show business. In 1903, he journeyed with the Wild West show to England again. Ticket sales were nowhere near what they had been on earlier European tours, and Cody spent long days sitting in his private railroad car. “I am going to get out of this business that is just wearing the life out of me,” he wrote his sisters. “[T]here is such a nervous strain continualy. And the thing has got on to my nerves. And this must be my last summer.”94 He was too tired much of the time even to be convivial. “I do not go to hotels any more for I haven’t the strength to be even talked to. The only ray of pleasure I have is when I get to thinking of dear old TE [Ranch] and the rest I am going to get there.”95

By this time, it was becoming abundantly clear that Cody and his various partners in the Big Horn Basin had vastly underestimated the cost of irrigation. The Cody-Salsbury plan to irrigate 60,000 acres north of the Shoshone River proved much too expensive even for the most successful of showmen. When Cody and Salsbury commissioned an engineer’s estimate of the costs, which included irrigating lands north of the town and providing the town waterworks, even the cheapest alternatives were estimated at a staggering $742,000.96 Even if they sold water rights to every acre at the highest price the law allowed, their profits would amount to only $158,000, and that only if there were no other expenses along the way: no lawsuits for flooded fields or washed-out headgates, no recruitment of settlers or advertising. By 1901, it should have been clear: irrigation did not pay.

And yet Cody continued to pour money and effort into developing the Cody-Salsbury segregation. Part of the reason was that he had an eye on the Mormons, who had developed irrigation systems not only in Utah but downstream on the Shoshone River, at the town of Lovell. Since arriving in 1900, a small Mormon colony had succeeded in building a town and began eyeing nearby parcels for an expansion. First in their sights was the Cody-Salsbury segregation across the Shoshone River, which they claimed should be returned to the public domain because Cody and Salsbury had yet to deliver the water they promised. Cody, who had faced off against imaginary Mormons in his stage plays, now spent considerable effort keeping his segregation from falling into their hands.97

But if their expanding horizons made him suspect there was potential for more cash in irrigating the desert, he drew the wrong conclusions. Mormon irrigators had a critical resource—communal labor—which Cody town did not. Farmers in Cody wanted the ditch dug for them; Mormons dug their own, collectively, as part of a greater spiritual effort to reclaim the wilderness. They were not fixated on how much money the ditches could make. They were, rather, bound by a spirit of collective religion.

Distracted by the Mormons, Cody appears not to have realized that his own frustrations in the irrigation business mirrored those of other capitalists. From 1894 to 1923, only one in twenty Carey Act projects made a profit. Ditch investments across the arid West paid so poorly that few investors could be found. Private funding of western settlement all but evaporated.

In 1902, Congress sought to remedy the shortcomings of the Carey Act with the Newlands Reclamation Act, a law that dramatically remade the landscape of western irrigation. Overnight, digging and financing large-scale irrigation works became a federal responsibility, administered through a new agency, the U.S. Reclamation Service.98

The Cody-Salsbury segregation was ideal for a large-scale irrigation project, and officials from the new agency were after it almost as soon as they had offices to work from. A dam across the Shoshone River would allow them to build a canal across the high northern bench and water a huge tract of land for settlers. Cody himself had made the same assessment, but he was unable to find the funding he needed, and the financial resources of the Reclamation Service far outstripped his. Where he scrambled to raise money in the tens of thousands of dollars, the government planned a network of dams, tunnels, canals, and laterals, and within months had appropriated $2.25 million for the project.99