CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

End of the Trail

FOR TWO YEARS following the trial, Cody toured Europe, in a figurative exile that largely kept him from the public eye in the United States. In France, where he took up the reins of the Wild West show immediately after Judge Scott rendered his decision, divorce and extramarital affairs were less stigmatized, and details of his personal life were less renowned. In fact, 1905 was the third year of a four-year European tour arranged by managing partner James A. Bailey (whom many suspected of keeping the Wild West show in Europe to protect his American circus, Barnum & Bailey, from competition). In 1903, the Wild West show had opened at the Olympia Theatre in London. After two weeks, the show moved to Manchester for three weeks, then went to Liverpool for three more, and on to a tour of the provinces that lasted until October. The year 1904 saw Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World in Wales, Scotland, and smaller English cities, inscribing the legend of Buffalo Bill in places like Penrith, Rochdale, and Macclesfield. In 1905, the show opened in Paris, then moved into the French countryside—Cholet, Vannes, Chateauroux— finishing in November in Marseilles. There, the Marquis Folco de Baroncelli and the poet Frédéric Mistral met Buffalo Bill and Pedro Esquivel, and Baroncelli began his long friendship with Jacob White Eyes and Sam Lone Bear.

In 1906, Cody—still following Bailey’s schedule—stayed clear of the American scene again. Opening in Marseilles, the company toured the south of France, then Italy and Austria-Hungary (with ten days in Budapest and brief appearances in Temesvar, Ungvar, and Brasso). There was a brief foray into today’s Ukraine and Poland, with a stop in Kraków, and then a return swing through Germany and Belgium.1

These appearances were by no means unsuccessful. Cody donated $5,000 to the survivors of the Mt. Vesuvius eruption in 1906, and $1,000 to the victims of the San Francisco earthquake.2 But that year, an epidemic of glanders struck the show horses in France. Show handlers had to destroy two hundred animals.

On top of these losses came the death of James A. Bailey, whose heirs found in his papers a note for a $12,000 loan to William F. Cody. The note was several years old, and Cody claimed he had paid it. But if he had, Bailey’s heirs insisted he do so again. Buffalo Bill would not be retiring anytime soon.3

In 1907, the Wild West show finally returned to the United States, where it played the remainder of its days. The show was still a large draw, and newspaper reviews mostly ignored Cody’s scandalous divorce trial. Instead, they portrayed the aging showman as a venerable, fading entertainment. They asked if this was his farewell tour. When he replied it was not, they treated it like one anyway.4 In part, they responded to his appearance. He looked old. Although journalists still described his hair as long, the tresses were a wig. Outside the arena, he often went without it, his bald pate covered only by a hat.

But the emphasis on Cody’s imminent vanishing was also a way of diminishing the controversy around him. He could not be a disruptive force if he was about to disappear, and over the last decade of his life, the dominant theme of his newspaper coverage was his approaching death.

His persona underwent a subtle shift, seemingly at his own direction. After his return from Europe, his show programs dropped all mention of his role as domesticator. There were no references to his family, no illustrations of Scout’s Rest Ranch, no poetry about Buffalo Bill and his babies. Indeed, show publicity referred only vaguely to the details of his private life at all. Programs no longer spoke of him as the embodiment of progress. In 1907, audiences read about his frontier heroics, his business and show successes, especially the show’s European travels. There was also a two-page spread on Cody town and “The Cody Trail through Wonderland,” with “Views of Yellowstone Park—Now Accessible on South via Cody by C. B. & Q. R. R.”5

The show itself did reprise elements of Cody’s old frontier heroics, with his first-ever re-creation of “The Battle of Summit Springs” which both complemented the show finale of the “Attack on the Settler’s Cabin” and offered audiences a bridge to a distant, frontier past that preceded the recent scandals. Show programs gave a detailed history of the battle, and the now-aged General Eugene Carr even ventured a personal testimonial in which he averred for the first time that Cody had killed Tall Bull. 6 At some point after 1907, Thomas Edison filmed the tableau, and the clip survives:

Two white women arrive in the arena with the victorious Cheyenne, who sing and thrust their lances at the sky. Tipis go up as the two captives recline nervously on the ground, watching the activity around them. Two Cheyenne women rouse the white women and try to shove them into a tipi. They resist. A chief comes along, and shoves them in. They emerge, arms flailing at their captors. The chief pushes them back inside. Then comes the cavalry charge, the Indians are routed, and Buffalo Bill himself, now an old man, dismounts to shake the hands of the liberated captives.7

But the search for an ending which now dominated Cody’s life began to permeate the entertainment. Had Cody retired with founding a town he could have made his life correspond to myth, with settlement and fixity succeeding the nomadism of his show career.

Instead, he scripted his now-anticlimactic life back into his show, abruptly abandoning the domestic finale just as he had left Louisa. After twenty-three years of marking the show’s climax, the “Attack on the Settler’s Cabin” disappeared. Never again would audiences watch the old scout ride through circling Indians to rescue the little pioneer family. The show’s culminating attractions in subsequent years included “auto polo,” riding tricks of different nations, and, reflecting the rise of collegiate athletics as manly training and entertainment, football games on horseback between cowboys and Indians (with a round ball some five feet in diameter).

As unsatisfying as these finales were, Cody’s search for an ending in a sense reflected both his attempted divorce and shifting public attachments to the West which the old performer probably sensed. The show increasingly competed with movies, and among the earliest of these were what became known as “westerns.” The Great Train Robbery was released in 1903, and was popular enough to generate many imitators. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West was among them: the 1907 show included a segment called “The Great Train Hold-Up and Bandit Hunters of the Union Pacific,” featuring an automobile mocked up as a locomotive, in front of a giant panorama of Pike’s Peak.8

Although many assume that western films were merely Wild West shows brought to the screen, there were significant differences between them, which suggest some of the challenges Cody faced in his effort to compete with them. The films built on the literary structure of the western novel, which dates its birth to 1902, the year Owen Wister published The Virginian. Wister’s novel became the template for the western genre prior to World War II. The Virginian made many contributions to western mythology, not the least of them a distancing of western heroes from domesticity. We may attribute the western’s antidomestic leanings to a reaction against the domestic novel and reform Christianity, as Jane Tompkins has argued, or we may take the view that Wister sought to reassure men that they remained firmly in charge even in “the Equality State” of Wyoming, where women had the vote, as Lee Clark Mitchell suggests. Either way, The Virginian ’s plot turns on a new kind of subordination of the independent woman to the novel’s hero.9

In Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, and in many nineteenth-century dime novels, heroes raced to rescue women bodily from the clutches of evil. The woman in the settler’s cabin, or the women in the wagon train, supported the armed combat of their men without hesitation. The alternative was abduction and subordination to a primitive and racially “other” regime.

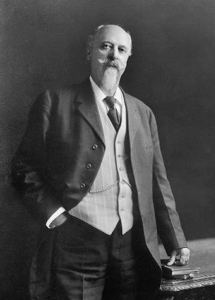

William Cody, c. 1915. Almost bald, Cody wore a wig in the arena, probably from the 1890s onward. But he did not try to cover up outside the show and often dressed like the financier and successful capitalist he longed to be. Courtesy Denver Public Library.

With The Virginian, the central trope of the western becomes a hero who ventures out to battle evil against the wishes of the good woman. In fact, his passage to the showdown is marked by his turning away from the woman, who is left indoors and who has announced that she will leave him if he insists on fighting. By venturing out the door, and into the street, the hero announces that he will forsake the woman and the domestic order she represents in order to defend the honor he embodies. In the western, heroes must renounce domesticity to fight villainy.

Sometimes, this development is resolved by the reassertion of domestic harmony, but only on the hero’s terms. After killing the bad man, the Virginian is taken back by his love, Molly Wood. Thus, she validates his violation of her wishes.

In westerns throughout the twentieth century, the climactic scene of The Virginian, with its domestic gender war followed by a showdown, was repeated in various forms. It was vitally different from the climax of the Wild West show. Where the heroes triumphed over nomadic savagery in the Wild West show, they were energized by the domesticating influence of women. Indeed, as we have seen, the presence of white women was the signature “racial” characteristic that allowed white men to vanquish Indians in the first place.

In the western, on the other hand, the protagonist vanquishes not one but two very different adversaries: the woman, who must be refused, and the villain, who must be killed. Indeed, the refusal of the woman’s wishes is the necessary precondition for the killing. Thus, the modern western emerges as a symbolic defense of manly honor in ways that require denial of the constraining power of home and womanhood. Indeed, the domesticating influence of woman becomes a chief threat to the hero, who needs violence to underscore honor and integrity and—though she does not understand this—to defend the woman’s honor, too. Indeed, her moral blindness to the need for killing is a sharp contrast to the moral clarity of the hero’s vision. 10

Of course, in a thousand ways, the picture of western centaurs racing home could still resonate with this myth (picture the desperate race to the cabin in John Ford’s The Searchers). But a symbolic homecoming of western heroes, like the finale of the Wild West show, perhaps brought the scout and his cowboys too close to home to be comfortable after 1907. It certainly clashed with the needs of the western as it developed in the twentieth century: thus the final scene of so many westerns, echoed and reasserted in The Searchers, when the hero, having restored the abducted woman to her family, walks away from the cabin and back into the wilderness.

Given his genius for tuning his mythology to national longings, it would be hard to imagine that Cody was completely unaware of these shifting cultural predilections. He practically voiced them himself, when he explained his reasons for wanting a divorce from Louisa in 1904, vowing to make a new home in the solitude, in “that new wild country” where he could “be away from trouble—domestic trouble.”11

In any case, it was peculiarly fitting that the show which claimed to tell the nation’s history and the biography of its star and creator ceased to include the “Settler’s Cabin” tableau shortly after he made a public, and losing, attack on his own marriage. Even more fitting that the man who had inscribed his life into western myth, and the myth that he reenacted back into his real life, in a sense sought to abandon the old climactic home defense, for a departure into the wilderness. As movies began to find their way into popular consciousness, Cody sought to inscribe what would become the primary denouement of western film into his real life.

THE ABANDONMENT OF the “Settler’s Cabin” paralleled his alienation from Louisa and his domestic circle, but it also corresponded with the final failure of his town-founding dreams. The town of Cody had broken free of him with the completion of the money-losing Cody Canal. But back in 1904, the railroad had given him a half interest in the town of Ralston, thirty-five miles east of Cody and on the other side of the Shoshone River, to persuade him to cede the Cody-Salsbury segregation. As soon as the Reclamation Service built its canal, this swath of dry basin soil would become town lots. Although he would have to split the profits with the railroad, Cody anticipated a handsome profit.12

But water for the site was slow in coming. Cody wrote dozens of anxious letters from the road, admonishing officials to begin construction of the canal, and to prevent downstream settlements, especially the Mormons at Lovell, from siphoning off water and decreasing the attractions of the north side canal for the government.13

With the railroad as his partner and the government promising to build a canal, he was all but certain the town site would flourish. But shortly after the Reclamation Service took over the irrigation project, Ralston’s prospects suddenly dimmed, as government authorities began to plan a new town at the site of their headquarters, midway between the railroad town sites of Ralston and Garland.

Rumors of the town’s creation preceded the actual staking out of its grid by some years, and Buffalo Bill worked Wyoming’s congressional delegation and the governor’s office to stop its construction, out of fear it would diminish Ralston’s prospects. Initially, the Reclamation Service denied any plans for a permanent settlement.14

Not satisfied with the explanations that he was getting and worried by the rumors of a town, Buffalo Bill himself wrote an appeal to President Theodore Roosevelt to request his help in relocating the government’s town elsewhere, lest “the old pioneer” again meet with hardship. 15

But Roosevelt was reluctant to interfere with a government agency. In 1908, the Reclamation Service announced they would begin selling town lots at Camp Colter, which would soon bear the name of Powell (named for the great western surveyor and irrigation advocate, John Wesley Powell). The new town’s proximity meant few settlers would be tempted to Ralston. Railroad officials objected. They had anticipated that the Burlington & Missouri—not the government—would be building towns on the new project.16

But the most vehement denunciations came from William Cody, who roared his objections in a small flood of letters. He had given up his segregation on the north side of the Shoshone River at great personal expense. “No one at that time had any idea that the Great National Government was going into the townsite business, and if the agents of the National Government contemplated the laying out of a town they did not mention it.” Moreover, they had implied the opposite. “They gave me to understand that Ralston should be the townsite and a town should be established there and . . . I perhaps would be able to make back from the sale of town lots some of the money which I had expended on that North Side proposition. . . .”17

He pleaded his case as the agent of progress, the man who opened the Big Horn Basin to settlement and who deserved better. The region was a wilderness when he found it, peopled only by a few backward ranchers. “They discouraged the advancement of civilization. They tried to discourage every new home builder whom I brought into the country . . . and in fact discouraged them to such an extent that they would leave the country and the first settlers whom I got to farm and remain I had to keep at my own expense for a year or two, furnishing them teams, farming implements, provisions, etc., until they raised a crop.”18

He claimed that he and his partners “had to keep lawyers employed at Cheyenne continually to formulate laws under which the Carey Act could be handled.” They gave the river a new name to attract settlers, and hired engineers to make the canals possible, and Cody himself persuaded the railroad’s president to build a line into the basin (a claim which was at best overstated, as we have seen). He brought English investors in 1903, and then asked them to leave so the government could develop the north side. Had he been allowed to proceed back then, the entire project would have been completed by now. He had spent something like $20,000 on the north side, and he had given up a lucrative partnership with his English capitalists, too. “This project has cost me a fortune, besides years of labor and anxiety saying nothing of hard work, but that is what the pioneer generally gets.” 19

Cody had a point. The federal government built no towns on the railroads. What right had the Reclamation Service to build towns that would compete with his?

But inside the offices of the Reclamation Service, the situation looked very different. What right had the government to stand in the way of settlers who wanted a town at Powell? By 1909, the government had spent over $3 million of the public treasury on the Shoshone project.20 As an arm of a democratic government, the office was more constrained to side with settlers than railroads and other town builders had been. Cody presented this closing battle of his long career as a fight between an old frontiersman and usurping bureaucrats like Henry Savage, the supervising engineer of the Reclamation Service at Powell, who was “determined to deprive me of any benefits arising from the sale of lots in the town of Ralston,” and who “forces all people to accept lands near Powell . . .”21

But in reality, Cody’s plans for Ralston were not undone by Savage or anyone else in the government. If anyone was to blame for the failure of his last town-site speculation, it was the middle-class settlers of Powell, who wanted a town near the tidy government offices of the officials who provided their water. As Henry Savage pointed out, settlers were spending a lot of money on Reclamation Service water, about $35 per acre. Having a town closer to their homes—at Powell—would keep their other costs down, “and the question to be decided is whether the proceeds from the townsite should go to the benefit of settlers who produce the value, or to others,” like William Cody.22

In fact, settlers demanded the sale of lots in Powell. Authorities merely gave them what they wanted. “We believe that creditable business houses would be erected here immediately if title to the land could be acquired,” wrote these home seekers in a petition to the Reclamation Service, “and we believe that it would greatly encourage prospective settlers if the town were put upon a sure basis....”23 At the opening auction of Powell property on May 25, 1909, settlers bought twenty-six lots. “Several business houses have been erected since the sale and others are in course of construction,” wrote one observer at the end of 1909. “A bank and the usual lines of staple businesses are represented, as well as the principal professions. A commercial club has been organized by the business men to promote the interests of the town. Schools and churches had been established before the opening of the town site and continue in a flourishing condition.” 24 Nobody prevented these middle-class, entrepreneurial people from moving to Ralston. They simply refused to go. The government did not betray the old scout. In a sense, his audience did.

In so many ways, their decision reflected the broader trend of middle-class politics. Clashes between monopoly capital and organized labor had so agitated the Gilded Age that by 1900 most Americans believed the partisans needed restraint. Theodore Roosevelt’s administration and the two administrations that followed gave it to them, in a form of governance that defined a new age, the Progressive Era.

From 1900 to roughly 1918, reformers and government regulators attacked corporate excess and market irregularities with a host of new commissions, boards, and agencies. In the West, federal agencies, from the Bureau of Reclamation to the U.S. Forest Service, regulated access to resources to guarantee abundance and prevent the clear-cuts, land swindles, and range wars of an earlier day. 25 Railroads still built towns in the West, but on federal reclamation projects, they had far less sway than they had had on the plains of Kansas when they ruined Cody’s town of Rome. The day of the railroad town was not yet done. But as Cody’s losses in the Big Horn Basin showed, the day of the government town had arrived.

There were powerful economic reasons for Cody’s financial failure in the Big Horn Basin. The Reclamation Service had resources no private capitalist could match, and along with a host of other federal agencies, they reshaped the West into the U.S. region built more than any other on federal dollars. Although reclamation projects seldom met expectations, and disappointments soon turned the agency from building country homes to building huge dams for urban reservoirs, Reclamation Service officials were wildly successful compared to the private capitalists who preceded them. In the next six decades, the federal government spent $6 billion on western irrigation projects for farms and cities, bringing unprecedented material wealth and new possibilities to places like the Big Horn Basin, planting small middle-class settlements like Cody and Powell where only wind-whipped sagebrush had grown.26

Buffalo Bill’s town-site dreams sprang from an earlier American West, in eastern Kansas, where well-watered valleys allowed speculative capitalists like Isaac Cody to found towns without subsidies. William Cody came of age in a West where corporations like the Union Pacific received federal subsidies in the form of land grants and concessions. Now, homeowners were federally subsidized, and they had a voice in where the towns grew. This new West, with its irrigated homes and federal agents anxious to do the bidding of their owners, blew away Cody’s dreams like smoke from the embers of a prairie fire.

WITHOUT A MANAGING PARTNER after Bailey’s death in 1906, Cody was exhausted by the organizational work of his show. At the end of the 1908 season, Bailey’s heirs sold a one-third interest in the show to Gordon “Pawnee Bill” Lillie. Gordon William Lillie was born in 1860, in Illinois, the son of a flour mill owner. When the family moved to Wellington, Kansas, in 1876, the sixteen-year-old boy spent a year as a trapper, then a brief season on a cattle ranch before moving to the Pawnee Agency in Oklahoma, where he became secretary and schoolteacher, and eventually a translator. He was a head shorter than Cody and his own frontier imposture drew heavily on Buffalo Bill’s example. A onetime employee of Cody’s (he had been a translator for the Pawnees in the Wild West show’s debut season of 1883), he created his own Wild West show in 1888, becoming a somewhat uneven competitor for Buffalo Bill’s entertainment. This longtime show rival would now take up the reins as Cody’s managing partner.27

Despite the competition, Lillie idolized Cody. He eagerly bought up Bailey’s interest apparently out of desire to work with Buffalo Bill, and to attach himself to the most famous Wild West show of all.

He found Cody anxious and distracted by his financial troubles. “In his business dealings, he was like a child,” recalled Lillie. “He apparently cared nothing for money, except when he wanted or needed to spend it. Then, if he did not have it, or could not borrow it, it made him sick—actually sick, so that he would have to go to bed.”28 The Bailey heirs were still demanding payment of Cody’s outstanding $12,000 loan. Lillie negotiated a deal, buying out the Bailey heirs and paying off Cody’s debt. He then allowed Cody to buy back enough of the show from that year’s profits to make him half owner. The move was generous, but also fair. Cody’s Wild West comprised most of their joint show and his presence was the main attraction. 29

The two impresarios then combined their companies to create “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West combined with Pawnee Bill’s Great Far East.” Fans called it the “Two Bills’ Show.” Virtually every segment of the show was one of Buffalo Bill’s standard features, the exception being one segment called “A Dream of the East,” in which elephants, camels, belly dancers, and Arab warriors made a circuit of the arena. The array of exotic Oriental wonders dissipated the coherence of the frontier narrative, but it also provided the Wild West show more of a sensual edge, for “oriental” motifs had long been associated with the relaxation of Puritan constraints. The show had some huge successes. In 1908, a two-week stand at Madison Square Garden sold out, and the partners grossed $60,000 in Philadelphia.30

In 1910, John Burke proposed advertising Cody’s imminent retirement as an inducement to audiences. The partners agreed on a three-year tour that would present Cody one more time to the public, appearing in no place more than once, allowing him to claim each appearance to be “positively” his “last performance” at that location. Kicking off the 1910 season, Cody gave his first of many farewell speeches to a hushed crowd. “Out in the West I have my horses, my buffalo, my staunch old Indian friends, my home, my green fields—but I never see them green. . . . My message to you is one of farewell . . . and I take this opportunity to emphatically state that this will be my last and only professional appearance in the cities selected, as no return dates will be given.”31 “Buffalo Bill Bids You Good Bye,” said one program cover. Another leaflet of 1912 announced his retirement with the announcement, “Buffalo Bill, Back to the New West. The Old West I Leave With You.” Inside was a list of his many business concerns, especially in the town of Cody.

By no means was the show unprofitable. The 1910 season saw the two owners split a $400,000 profit, and even in 1912, a comparatively weak year, it reportedly made them $125,000.32

On these proceeds, perhaps Cody could have retired. Lillie spent $100,000 on a mansion for himself and his wife in Oklahoma, and stashed a like sum into his bank account.33

Cody threw his money down a hole. In 1902, Colonel D. B. Dyer, a member of New York’s Union League Club, introduced Cody to a prospective gold mine in Arizona, at the Campo Bonito mine works, some forty-three miles from Tucson.34 Cody began investing. The following year, after seven months of tunneling, his managers reported a gold strike. Cody (who was beginning to realize his Big Horn Basin effort would not pay off) thought his retirement was now secure. “It seemed like a great load had suddenly been taken off me.”35

Gold continued to appear in smaller quantities, just enough to keep Cody hopeful. But profits from the mine proved as elusive as the proceeds of his towns. The showman emptied something like $200,000 into his Arizona mines.36 He sought investors and wrote almost as many letters about the shafts as he had about ditches in the Big Horn Basin. Like his other investments, he complained bitterly about managers who failed to keep him informed, and he pretended to supervise the mine as much as he did his show arena.37

There was a degree of showmanship in soliciting investors that appealed to him. He led trips to Campo Bonito to convince the parties he brought along to invest their money. The guide and showman understood the value of providing these clients an authentic experience of the mining West. He fixed up his own cabin with western relics, including Yellow Hair’s scalp. 38 Letters to his managers instructed them to prepare suitable camping amenities for the travelers, as if Campo Bonito was a new arena for his ongoing show. “Will you have the Mrs. Thomas House sealed with light colored burlap, as it’s a rather dark room—two beds like I had in my teepee—nice blankets, pillows &c. A curtain to hide the beds . . . Wash stand—fix it up something like my teepee . . . writing desk &c. . . . Hope you sowed some barley so it will look green like last winter. . . . I wish you would have the Mrs. Thomas house white washed, also the store. It would help the looks greatly. . . . You should get the soft burlap, 56 inches wide, and tack it on the walls—hard burlap goes on with paste.” 39

Cody never deceived investors about his profits. Despite his attention to the entertainment of his guests, he did not hide the fact that the mine consistently failed to turn a profit. There were numerous obstructions to mining and milling, and the promised ore failed to materialize.40 The show he ran at Campo Bonito was honest, and very unprofitable.

But he was so busy running that show—or maybe he was just credulous— that he failed to realize another show was operating at his mine. Lewis Getchell was the Arizona partner who had lured Cody and Dyer into the operation. Getchell was notorious for promoting worthless commercial properties, and he found an easy mark in Cody, whose faith in the mine sprang from the fraudulent report of a crooked mining engineer (whom Getchell had commissioned, of course). Getchell lived high on Cody’s money, sending the showman fake receipts for his expenses and pocketing the money the showman sent. At the same time, he employed forty-five people to scrabble in the tunnels, making the mine look potentially profitable.41

Other observers were not fooled. One engineer on a neighboring claim judged the mine “a tremendous swindle and I am very much afraid that Cody is innocent and Getchell is playing him for a sucker.”42

In a sense, Cody was defrauded by Getchell’s show and then constrained by his own public image. In 1912, perplexed by the financial failure of the mine, Cody’s partner, D. B. Dyer, requested an evaluation by a qualified mining engineer. The engineer, E. J. Ewing, caught a worker seeding the mill with refined minerals to make the ore look richer than it was, and he uncovered the kickbacks Getchell had engineered. Beyond losing his job, Getchell paid no penalty. Fear of adverse publicity kept Cody from filing charges. After he was taken in by Getchell’s staging of a “working” mine, his need to protect his own show reputation as a clear-sighted westerner kept him from seeking legal recourse.43

By this time, Cody had spent his great profits from the 1910 season, and even though the mines began making a small profit (mostly from tungsten, used in new electric lightbulbs), it would take many years for them to return the money Cody had spent. Dyer died soon after the fraud was uncovered. Cody, unable to finance more operations, leased the mines to Ewing. For the rest of his life, he searched in vain for buyers.44

HIS PRIVATE LIFE was solitary after the scandal of the divorce trial. The fate of Bess Isbell remains mysterious, although documents offer intriguing hints. In 1906, Isbell met Cody at the Hoffman House in New York. There she signed over her power of attorney to W. J. Walls, Cody’s lawyer in Wyoming, whom she instructed to sell her forty-acre ranch. After deducting expenses, Walls was to send the proceeds to her mother, Mrs. Julia Isbell, of the St. James Hotel, Denver. Why she wanted the money sent to her mother is not clear. But perhaps, as Cody had testified, she had tuberculosis. Whatever her fate, she disappeared from Cody’s life after 1906.45

Cody was alone in 1910 when his daughter Irma, now living in North Platte with her husband and children, persuaded her father to visit the town that had turned against him at his divorce trial. Encouraged by reports from Louisa’s friends that she wanted to take him back, town newspapers looked forward eagerly to the return of the old scout. Once again greeted by a large crowd of well-wishers and the town band, Cody was delighted. “Almost one hundred of the best people were out to the ranch for a smoker,” he reported to his sisters. “Today at 2 p.m. the Commercial Club gives me a reception. . . . So you can see I am in the lime light again. And hardly know how to meet it.”

News flashed along the wires that he and Louisa were reunited. But they were not. “I haven’t seen Lulu,” Cody wrote. Although Louisa had expressed her longing for a reconciliation to friends and family, when he tried to visit, she refused to come out of her bedroom. He knocked softly. He pleaded. But the door remained closed.46

Sometime the following year, she relented. Evidence is thin and contradictory, but the family story is that he stopped in North Platte in July. Daughter Irma, her husband Fred Garlow, their children, and Arta’s orphaned children contrived to leave them alone in a room together. When they emerged, Louisa and William Cody were reconciled.47

The Codys were not without resources. They still owned Scout’s Rest Ranch and Louisa’s house in North Platte, called the Welcome Wigwam. They owned the Irma Hotel and the TE Ranch in Wyoming. But the expenses of the Two Bills show were onerous. The partners were supposed to split the $40,000 cost of wintering livestock. Cody, desperate to raise his $20,000 share after a poor season in 1913, took a six-month loan from Henry Tammen, a shady impresario who owned the Sells-Floto Circus. Tammen also owned the sensationalist newspaper the Denver Post, which had reported lurid details of Cody’s divorce trial in screaming red headlines. Now it reported the loan and a supposed condition: Cody had agreed to a partnership with Tammen’s circus instead of with Pawnee Bill Lillie, beginning the next season.48

Cody denied he had made any such agreement, but Lillie was furious. 49 Tammen would not likely have been able to enforce the condition even if Cody had agreed to it, since Cody could not unilaterally break his contract with his partner. But Tammen had another scheme for moving Lillie out of the picture. If he could not break the Cody-Lillie partnership, he would break the company.

In 1913, when the show camp arrived in Denver, days from Tammen’s deadline for repayment, the Two Bills were already faring poorly from rain and low attendance. The slick publisher had maneuvered a series of foreclosure suits into the courts, and the show was attached for payment of Cody’s $20,000 loan. The sheriff and his deputies arrived on the showgrounds, seized all cash on hand, and then sold all properties at auction. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West was bankrupt.50

Deprived of his own show, and now under salary to Tammen, Cody toured with the Sells-Floto Circus in 1914 and 1915. The circus had dirty tents and rotting ropes, and at one showing it was nearly flooded out of existence. Still, Cody’s life was not all bad. His salary was sizable: $100 a day, plus 40 percent of receipts over $3,000. He rode on horseback to introduce the show, but forsook his shooting acts. He had a private car on the train, a cook, a porter, and a carriage driver. Louisa traveled with him for free. “She has enjoyed the trip immensely,” he wrote to sister Julia.51 Years later, one fellow circus performer recalled, “He kept pretty much to himself in his private dressing tent. Had a certain amount of dignity about him that I admired. Was a handsome man for his age and still looked wonderful on a horse.”52

The misadventure with Tammen was compounded by Cody’s foray into filmmaking, in which he secured the backing of Tammen and Tammen’s partner, Frederick G. Bonfils, in the creation of “The Col. W. F. Cody (‘Buffalo Bill’) Historical Pictures Co.” Given the significance of the Wild West for formulating western myth and the spectacle of “moving pictures,” making films seemed to many a fitting culmination for Cody’s latter years. Cody envisioned a movie, The Last Indian War, that was educational and authentic, and thereby secured permission for it from both the army and the Department of Interior, which retained authority over Indians. He then set about gathering actual participants from the Plains campaigns and a slew of younger actors and extras to make his one and only motion picture.

Much of Cody’s initial success in the filming came from his friendships with Indians, which he tended carefully. Back in 1909, there had been a flash of the discontent he occasionally encountered at Pine Ridge after one of the show contingent, Good Lance, fell sick and was left in a hospital in Garden City, Kansas, where he died. The tribal council (which included some Indians who had formerly performed with the show) sent a letter to the White House, demanding Wild West shows, including Buffalo Bill’s, be banned from hiring Indians. At least some of their anger stemmed from the failure to return Good Lance’s body. “We want that dead body to be sen[t] back over here,” wrote the council. “So we want him [Buffalo Bill] to do as what the Oglala Council wanted.”53

For decades, Indians and others who died on tour were buried near their place of death. But in 1913, contracts for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Far East Combined included a new clause, stipulating that in case an Indian employee died on tour, Cody and Lillie would “make all arrangements and pay all expenses incident to the preparation of the body for burial and transportation of the body to Pine Ridge Agency.”54

Cody followed on this gesture, the next year, as he began hiring Indians for his film. He hurried to pay back wages owed to those Indians who had been on the lot in Denver the day the sheriff seized the cash box. Since the cast could not be paid until the bankruptcy was settled, Lakotas with the show, like everyone else that year, had gone home without their salaries. So, while filming at Pine Ridge, Cody secured a personal loan and paid some $1,300 in wages to his former employees. Lizzie Sitting Eagle, Alice Running Horse, Peter Stands Up, Ghost Dog, Iron Cloud, and many others received their back wages, as well as small sums for the support of young children who had been with the show in 1913.55

His support from the army secured for Cody the services of retired General Nelson A. Miles and three troops of cavalry. Filming began in September 1913. Cody soon expanded the project, from The Last Indian War, about the Ghost Dance tragedy, which he had never before reenacted, to The Indian Wars, including two battles, Summit Springs and Warbonnet Creek (where he scalped Yellow Hair), that were standards of the Wild West show. 56

Cody played his moment as film producer for all it was worth. Now he was not only appearing in the film itself. He also heightened the film’s authenticity by making himself the arbitrator between hostile forces, telling interviewers from film magazines that the Indians were fearful of the army and that he had talked them out of using live ammunition for the reenactment of the Wounded Knee massacre.57

These fictional tales titillated the public, but other attempts at authenticity were more costly and less effective. Miles insisted on reenacting central scenes in places where they actually occurred, forcing a fifty-mile trek out to the Badlands in freezing weather. Cody, who recognized a budget-busting production when he saw one, argued bitterly with the old general about the Badlands filming and other details, to the point that it reportedly ended their friendship.58

Ultimately, the film fared poorly at the box office, leading many to speculate that hidden forces conspired to destroy it. Chauncey Yellow Robe, a Lakota who differed with most of his Pine Ridge contemporaries on the usefulness of Wild West shows, denounced Cody and Miles for debasing the sacred burial ground at Wounded Knee “for their own cheap glory.” 59 There were rumors of a protest against the film by the tribal council, although it never materialized. Because the release of the film was delayed in Washington (where the army had to approve it for release, as a condition of using real troops in the film), there have been rumors for many years that the film was suppressed, perhaps because the massacre at Wounded Knee was too “realistic” to reflect well on the army, or perhaps because authorities in the Office of Indian Affairs disapproved of the final product.60

For all these rumors, it is unlikely the film offended a public once again fond of their army, as World War I raged in Europe. Wounded Knee stands as a black mark on American history, and the dark reputation of the event kept Cody from staging its reenactment during his Wild West show years. But the film evaded this problem by eliminating the massacre altogether, showing no women and children among the bodies in the ravine.

In fact, evidence suggests the film failed for other reasons which are both more conventional and more revealing. In order to secure permission to hire Indians, Cody promised that his film would also illustrate “the advance of the Indians under modern conditions.”61 So, with the battle scenes over, the audience watched clips of Indians in school and performing standard farm and business tasks. The Wild West show had never ended with such an anticlimax (which was, of course, why Indian office functionaries so disliked it). The western was still young, but it was already a popular genre, and The Indian Wars was no western. Audiences were less than thrilled by the story’s prosaic culmination. The authentic, primitive racial energies that spectators usually identified in Indians were erased in a denouement where the Indians became much like people in the audience. Watching Indians resist vanishing was exciting. Watching them after they had symbolically vanished was dull. Cody had turned his narrative over to the Office of Indian Affairs, and their achievement was to bore the public with a didactic lesson in Indian assimilation.

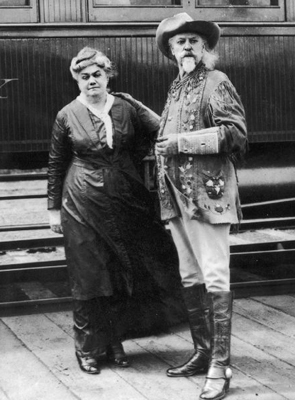

William F. and Louisa Cody, c. 1915. They traveled together in his later show days. Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

The tedious plot was one factor which undermined the film’s appeal. Another was that film was a less than ideal medium for Buffalo Bill Cody. The dispute between Cody and Miles over how best to achieve authentic scenes reminds us of Cody’s arena successes and suggests why film worked poorly as a vehicle for his own myth. He had pioneered an art form in which he danced across the line between fake and real, emerging from painted backdrops and then disappearing back into them, surrounding himself with frontier relics and fakery, real frontier people and actors dressed up like them, and begging audiences to separate the two.

Early filmmakers often constructed narratives about real historical figures. Marshall Bill Tilghman, of Oklahoma, made films about his exploits starring himself. To enhance the middle-class appeal of his movies, he toured with them and lectured boys in the audience to stay away from crime. Likewise, Cody toured with The Indian Wars for three weeks in 1916, once appearing onstage with Sioux warriors.62 But Cody was so aged by this time that he appeared less the frontier hero and more the grizzled Plains veteran. He was still interesting. But film was not as effective a form for testing the borders of truth and fiction, simply because it did not allow him to step out of the projection the way that arena performance did. Film worked best when it deployed scenery, lighting, props, and physical types to cue audiences, not necessarily when it showed “real” people on a flat screen.

Unfortunately the film remains a mystery, because the nitrate stock on which it was recorded disintegrated over time. Only a few fragments of it are known to exist.

As he waited for the film to debut, Cody endured more trouble with Tammen. After Cody had toured with the Sells-Floto Circus for two years, Tammen told him his debt was paid, then reneged and told him he still owed $20,000 and that he would have to pay it back with his salary. Cody wrote an old friend, “This man is driving me crazy. I can easily kill him but as I avoided killing in the bad days I don’t want to kill him. But if there is no justice left I will.”63

When Tammen arrived in Lawrence, Kansas, to meet with Cody, he was afraid to go into the old scout’s tent. When he finally did, they had a tense conversation, the upshot of which was that Cody agreed to finish the 1915 season with Sells-Floto. Tammen refused to cancel the loan, but he agreed to stop taking payments out of Cody’s salary. At the end of the season, Cody was without employment for the first time since entering show business. 64

Not to be deterred, he scrambled to put together a new show. Tammen claimed ownership of the name “Buffalo Bill’s Original Wild West,” so Cody combined with the 101 Ranch in Oklahoma to create the “Buffalo Bill (Himself) Pageant of Military Preparedness and 101 Ranch Wild West.” He enjoyed the year. His nephew, William Cody Bradford, toured as his assistant. Cody rode in the saddle again, shattering amber balls with his rifle from horseback as he had in days gone by.

Even now he struggled for the ambivalent middle ground. The country was fiercely divided on the subject of American neutrality. Military preparedness was a conservative slogan of those who favored U.S. intervention in World War I, on the side of Britain and France. When the new show played Chicago, home to thousands of German Americans, the proprietors changed the show’s name to “Chicago Shan-Kive and Round-Up.” (“Shan-Kive” was said to be an “Indian word” for “good time.”) The event, which resembled a rodeo and featured bulldogging by the likes of legendary black cowboy Bill Pickett, was a huge success.

Outside of Chicago, the show reverted to its Wild West format, with Pancho Villa’s raid on Columbus, New Mexico, as its crowning spectacle. 65

The show closed in November. Cody was not feeling well. He arrived in Denver on November 17, “sick with a bad cold and played out from the long hard season,” according to his nephew. He stayed with his sister May for two weeks, then returned to the TE Ranch, where he hoped to recuperate. He continued to fail, and he returned to Denver to seek medical help in the middle of December. His health “was up and down all the time,” recalled Bradford. To the end, he put on a show. “He did not want the papers to get a hold of the news and publish his sickness.”

Cody went to Glenwood Springs, hoping a mineral bath would restore his health. But he returned four days later, none the better. He died January 10, 1917. Louisa was with him, as well as his sister May and her family. Johnny Baker, his longtime assistant and virtual foster son, raced from the East where he had been trying to raise money for the next season’s show, but arrived too late to say farewell. Six weeks after Cody died, his longtime press agent, John Burke, also passed.

Cody left instructions to have himself buried on a hill overlooking the town of Cody, but Henry Tammen offered to pay for a funeral if the burial occurred in Denver. Some say Louisa took the publisher’s offer to revenge herself on the town of Cody, which she resented like one of her husband’s mistresses. Others say she had no money to bury him. In any case, the following June, William Cody was interred in a hole blasted into the summit of Lookout Mountain, overlooking the city of Denver and the Great Plains beyond, as a gigantic crowd of journalists, tourists, and sightseers looked on.

STILL HE RIDES, across our imagined horizon. In the years since his death, he has become, like so many other symbols, detached from his original context, a free-floating icon that may be, and has been, attached to different causes and ideologies. But this process was evident long before he died. By the time 1916 rolled around, Cody had been a theater and arena performer for forty-four years. His face and image, printed on innumerable posters, programs, and other show ephemera, were ubiquitous. He may have been the most photographed man of the period, and although the currency of the Cody face kept him in the public eye, it had a dark side. A person who has been through a historic event, whether a fight on the Plains, the march on Washington of 1963, or September 11, has more historical meaning and authority than has a mere drawing or photograph of that person or event. Reproduced images of authentic people cannot have the authority of real people. A mechanical reproduction, like a photograph, can be put to practically any use its owner can devise, as somber art or decoration, framed portrait or place mat.

Thus, when images of people or landscapes are mass-produced and widely distributed, the authority of the real is devalued. The face, the hair, the pose become symbols with meanings to spectators, but in the process they are often divorced from the history of the person or their setting. Americans who savored the proximity of the Wild West show’s real frontier heroes confronted a paradox. They placed images of Cody and his Wild West show in bedrooms, living rooms, and hallways to bring them closer, to claim some element of their frontier authenticity for themselves. But in substituting copies for the unique people and things in the show, and redistributing them in a private arrangement with private meanings, they diminished the power of the very history and tradition which Cody and other real people conveyed. 66 Many of the fans who bought souvenir photographs, books, and programs, to say nothing of Buffalo Bill toy guns, board games, puzzles, tin whistles, dime novels, buttons, and postcards, knew him more from this show business flotsam than from his arena performances. Inevitably, as his fame mounted, he lost authenticity.67

In this sense, William Cody fomented a mountain of representations of his own face and story to draw a following, then represented himself before crowds who came to watch. The show was not just an adventure of the hinterland. It was a heroic stand of the original against the dead hand of the copy. Cody’s optimistic, forthright confrontation with the artifice of modernity, in day-to-day life and in the painted, landscaped, eye-tricking arena which resembled the frontier but whose deceptions evoked the city, made him both the premier symbol of the natural frontier and a hero of artifice among the most modern people on earth. Reproducing his own image and selling it widely was a means of reminding audiences of his importance. But it also meant that by his last decade, the vast majority of his audiences knew him only as a showman with a putative link to the frontier. His ability to generate a flood tide of self-promotion helped ensure his renown. Then it washed him away, like a faded poster in the rain.

The peculiarities of Cody’s story, as a popular celebrity who hailed from the frontier West, so confound show business stereotypes that many have suspected, or believed, that he must have been the creation of somebody else. The debate over whether he was a frontiersman or a showman has continued in every Cody biography since he died. But as we have seen, during Cody’s life, even as he advanced to ever greater successes, many rivals and partners, from Doc Carver to Nate Salsbury, argued that Cody did not fashion his own success. Against these imputations, Cody partisans, then and now, have maintained that he was a genuine frontier hero who stumbled into fame, an innocent abroad in the world of modern amusements.

But as I have argued throughout this book, neither of these positions illuminates the vibrant culture of artful deception and imposture that characterized nineteenth-century American culture and especially that of the Far West where Cody came of age. True, he was influenced and shaped by many people and forces, but he was neither a simple creation of publicists and press agents, nor was he a lifelong ingenue. In his rise to fame and his long tenure as America’s premier showman, his own vision, talents, and burning ambition played the largest role. Hailing from a West that was practically a borderland between real and fake, full of charlatans posing as heroes and of everyday people invited to assume heroic poses, Cody learned the allure of that tense space between authentic and copy, regeneration and degeneration.

Americans imbued that space with a story about the ascent of civilization, and that narrative was so pervasive that settlers easily adopted it as their own, making themselves the protagonists of upward development, from hunting, to ranching, to farming, and commerce. Following that story, and claiming to live it, made Cody’s show resonate with public desires, even as audiences might question how real it actually was. Was he a frontiersman or a showman? Clearly, he was both.

In the end, we might say that Cody was partly a trickster, a boundary-crossing figure who appears in the myths of many cultures. Tricksters are usually clowns, monsters, ogres, or spirits. As various scholars have observed, they violate sensual taboos, and societies venerate them partly for the vicarious pleasure they provide. They also destroy old institutions and codes as they erect new ones. P. T. Barnum’s biographer, Neil Harris, calls Barnum a trickster because of the ways he loosened the grip of elite knowledge and encouraged Americans to enjoy their own powers of discernment. In elevating western history to a respectable show, in allowing Americans to believe that their frontier fantasies were not only real but embodied in his person, and in providing a means for Americans to accept frontier stories as an art form that was as respectable as any European play, Cody did much to destroy older notions of art and performance, and to usher in a new national mythology for the coming American century.

But tricksters are so dangerous they must be contained in the realm of myth and story. As flesh and blood, Cody could not remain a trickster. The failure of his suit for divorce was, among other things, a signal that he could not violate taboos with impunity. At the end of the day, he had to drape his life in standard morals.68 Louisa Cody died in 1921, shortly after completing her own memoir of her marriage, a deceptive if not artful book in which she recalled no bitterness, no mistresses, only a warm and loving marriage to the man she helped invent the Wild West show. 69

Many have accepted Cody’s publicity that eulogized him as, in his sister’s words, “the Last of the Great Scouts.” By this estimation, there could be no more like Cody, because the frontier had passed. While he lived, seeing his show became ever more imperative for those who would witness the fading West.

But if the death of William Cody and his generation of Lakota warriors, American fighters, and scouts severed historical connections between modern America and the frontier of history, there was still another, perhaps more powerful reason why there could be no more quite like Buffalo Bill. This was the demise of the story of progress itself. Indian war was never universally accepted among Americans even while it was going on. But progress, the rise of technology over nature and of settlement over the wild, seemed inevitable. Almost until the year of Cody’s death, it was yet possible to believe that western industrial society was the apogee of human development, the beginnings of a more peaceful, humane world, and even to fantasize that one person could embody its promise.

But the twentieth century was not kind to the story of progress. The trenches of World War I brimmed with blood, and the holocausts of World War II and the nuclear anxieties that followed made it hard to believe that technology was an unimpeachable wonder and moral boon. The dream of Buffalo Bill’s America, a frontier nation launched from Nature into the bright future of the Machine, suddenly seemed quaint and naive.

And yet, there remained one way in which Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show would find enduring resonance, down to the present day. Americans have relegated Indian fighting to that dark space reserved for troubled memories and moral qualms, as they should. (And Cody himself seems to have felt the same way about it, at some points in his latter years even denying he ever killed Yellow Hair. “Bunk! Pure bunk! For all I know Yellow Hand died of old age.”70)

But while the Wild West show was created to tell a story of the Indian wars, its show community itself has long since become Buffalo Bill’s myth, a symbolically inclusive congregation that seems to define some bright and optimistic moment in our collective past. If it was a traveling company town, a corporate workforce on the road that subsumed polyglot America under the ruling management of white men, there was a sense among its cast that they were part of something more. The many adventures of its optimistic and forward-looking cowboys, Indians, cowgirls, gauchos, vaqueros, and others stand out as something so surprising, so energetic and benign, that Americans and the world cannot help but find in them some resonance of a modern American promise.

In 1971, the entertainer Montie Montana, Jr., resurrected Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, vowing to imbue “the small fry with the spirit of the Old West as their Grandparents knew it.” When the show played Los Angeles, Harry Webb, a cowboy who had ridden in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West from 1909 to 1911, was seated in the stands. Webb was astonished at the “fine replica” Montana had assembled. “With a lump the size of an egg in our throat we dug a fist in our eyes and listened to the exact salutation we had heard hundreds of times as Buffalo Bill addressed his audience and introduced his Congress of Rough Riders of the World.” Webb laughed and cheered with the sports arena crowd at the bronc riding, the Indian attack on the Deadwood stage, the saloon fight of the cowboys, the wooing of an Indian maiden by her warrior lover, and the trick roping and bullwhip acts.

But as much as Webb wished the new show would succeed, he could not help noticing the absences and gaps in this reenactment of a reenactment.

No longer are there great spreads of canvas, [a] football-[field] sized arena, horse tent housing hundreds of arena and baggage stock and the half acre dining tent. Also, the huge ranges and steam boilers (that poured forth the aroma of breakfasts even before being trundled off a fifty car train . . .) were missing. Nor is there the chant of stake drivers as a circle of sledge hammers sunk hundreds of tent stakes in the earth. The old ballyhoo around concessions and the shouts of venders are also missing with this new Buffalo Bill Show. Nor will its Indians have their Sunday feasts of dog-stew on the show lot as of old. These scenes are gone forever. 71

As a community that developed a history of its own, the Wild West camp has long since become the larger and more enduring of Cody’s legacies. Even the continuing success of Cody, Wyoming, now home to eight thousand people and the remarkable Buffalo Bill Historical Center (which houses five state-of-the-art museums), cannot compare to the continuing fame of William Cody’s traveling company town. In the decades since Cody’s death, that “little tented city” has continued to fascinate the public long after Buffalo Bill’s Indian war exploits and the scalping of Yellow Hair faded into obscurity.

As we have seen, William Cody remains a respected figure among Lakota people, some of whom remember him as a good employer who provided opportunities which did not long outlive him. Pine Ridge remains one of America’s poorest communities. Although movies hired genuine Indian actors in the early days of Hollywood, film producers soon discovered that it was easier and cheaper to hire non-Indians to play Indian roles.72 Since then, Indian actors have waged a long and not unsuccessful struggle to win back their place in Indian performance. In doing so, they carry on the fight of Lakotas like Standing Bear, No Neck, Black Heart, and Calls the Name, who allied with Cody to fend off the Indian Service in the 1880s and ’90s.

As much as I have been able to explore the participation of Indians and cowboys and cowgirls in this show, I have attempted to open up what I see as the often unnoticed power of commodified performance—show business— as a means to adopt and adapt otherwise pernicious myths. Indians, immigrants, first-generation Americans, and native-born whites all flocked to Cody’s show camp, each with a powerful economic and social rationale for doing so. Although the Wild West show’s ideology was oppressive in its cultural messages of womanly domesticity and Indian subjugation, we have seen over and over again how performing it brought liberation, or something like it, to Standing Bear, Adele Von Ohl Parker, George Johnson, Annie Oakley, Broncho Charlie Miller, and a host of others.

The willingness of so many diverse peoples to attach themselves to Cody’s show validates his early recognition that frontier myth had about it much ambiguity, the necessary precondition for its mass appeal. Cody himself abhorred personal conflict and partisan fights. He found in politically vague frontier symbols a means to avoid the fierce political contests of his day. In recent decades, conservatives have appropriated western symbols for their political ends. In 1986, Wyoming’s congressional delegation joined a campaign to have Cody’s Congressional Medal of Honor restored to him, something that they achieved in 1989. A primary player in the effort was a taciturn Republican congressman named Dick Cheney, a fact which speaks volumes about the rightward tilt of the Cody legacy in recent years.

Yet during Cody’s life, the western myth was the province of no party. As we have seen, conservatives, reformers, and radicals alike found reasons to embrace his show. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West was aimed at the broad middle class in ways that allowed audiences to enjoy the amusement without taking sides on the contentious issues it called to mind. By being a show about history, in an age when Americans believed their history followed a course that was largely predetermined, the sense of inevitability allowed them to remain ambivalent about American cruelties, and to celebrate American success, without any consternation about their confidence in the nation, or lack of it.

The amusement both appealed to the mass public and helped to cement it as a public, and in so doing, helped create modern America as a functioning political whole. But the costs of this imposture to William Cody himself were considerable. If embodying the frontier myth gave him a continuing hold on America’s imagination, it made him peculiarly vulnerable to its narrative constraints as his life continued. Perhaps if he had been merely another businessman or a vaudeville star, his divorce case would have collapsed anyway. But to be a frontiersman and a showman at the same time was to walk a border between dark and light, a kind of lifelong high-wire act that in some sense kept the public on edge. To attack the domestic hearth at the center of the ideology of civilization was to change sides in the war on savagery, to court public condemnation. These were risks he intuited but only half understood. As we have seen, from the army officers who warily appraised their guides in the Indian wars, to Cody’s personal acquaintances and partners such as Bram Stoker, Nate Salsbury, and Louisa Frederici Cody, the scout projected a continuing tension between hero and renegade, the figure who ventured over the frontier line to do battle with the darkness, and returned either unstained by it and heroic, or secretly corrupted and malevolent.

The implications of this argument are many, but one important lesson to be drawn, I think, concerns the widespread popular ambivalence about the frontier in the late nineteenth century. For many years now, historians have explained frontier myth, and especially William Cody’s brand of it, as an unswervingly triumphalist story. We live in an anxious age, and it would be foolish to assert that the nineteenth century was not more confident than our own in many respects. But if there is one thing William Cody’s biography teaches us, it is that the nineteenth century was characterized by doubts about frontier conquest, racial degeneracy, the industrial order, and the failure of the western farm landscape to generate the wealth and security that the story of progress had promised. To construe frontier expansion as a moment of supreme confidence untarnished by reflection or hesitation is to ignore all the dark fears that underlay it.

William Cody could be as defensive and egotistical as any celebrity, but at his apogee he embodied the westward-moving, industrially modern American, who was both optimistic and ambivalent. To be sure, his cheeriness was palpable. He believed fervently in capitalism as his best bet for making lots of money (a bet he seemed to lose consistently). But his simultaneous devotion to Indian friends whose relatives he fought on the Plains, to industrial might and middle-class smallholders, to rural virtue and the ribald world of stage and arena, all suggest his lifelong straddling act, a remarkable unwillingness to choose sides and a talent for creating dramatic spectacle that made it possible for him to avoid doing so.

In so many ways, the show about the triumphant fixity of the settler was Cody’s way of calling attention to himself and avoiding the need to settle in one place. Like western film, which allowed generations to believe a frontier promise long after the frontier closed, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West generated such powerful mythic images that one could be forgiven for thinking they were real. Cody did not believe all the lies he told, but he did believe in the West as a region that foretold America’s bright future. No matter the dismal failures of his town canal systems, the bankruptcy of his mines, the expense of his ranches. The show became his most powerful token of the real West. Much more than a means of telling his story, it became the story. So long as it went on, not only did his life continue, but the story of the West continued, and the drama of onward, upward achievement continued with it.

One author recounts that when Cody’s doctor told the showman he had thirty-six hours to live, Cody turned to his brother-in-law, Lew Decker, with a deck of cards, and shrugged off the news. “Let’s forget about it and play High Five.”73

But his nephew, William Cody Bradford, suggests a less sure-footed ending, and one more telling. The doctors had done all they could, and Cody lay dying at his sister May’s house in Denver. Johnny Baker was away in the East, looking for money for the next season’s show. As if to announce one last time the seamless weave of his life and his show, and his determination to make the story of the West continue, during his last three days, as uremic poisoning sapped his vitality, he returned in his mind to his private railroad car, and imagined he was once more headed to a showground just down the road:

He would send for John Baker and lay down on the bed just as he did in his car and he would have his chair at the head of his bed. He would imagine that he was on the road with his show. He would ask me where we were and what time it was when we got in. He would lay in bed and smoke and read the paper. In fact he lived his life over again. He done just as he did when he was on the road with the show.74