rriving in New York in June 1918, Walrond was six months shy of age twenty. He showed the Ellis Island officials $160, told them he was a journalist, and moved into the Brooklyn home of his aunt, Julia King Nichols.1 A middle-class black community had formed in Brooklyn in the late 1800s, and Bedford Stuyvesant, the Nichols’s neighborhood, had become an enclave for West Indians, nine thousand of whom resided in Brooklyn in 1920.2 Local markets carried saltfish, callaloo, and other Caribbean staples. Italians, Poles, and Jews had supplanted the Dutch and English who gave the neighborhood its name, but now Caribbean sounds emanated from the stoops that adorned the brownstone row houses. Overhearing the conversations about Kingston and Bridgetown, the hum of calypso, or a discussion of the spice buns on Nostrand Avenue, a West Indian could fool himself into believing he had never left home.3

rriving in New York in June 1918, Walrond was six months shy of age twenty. He showed the Ellis Island officials $160, told them he was a journalist, and moved into the Brooklyn home of his aunt, Julia King Nichols.1 A middle-class black community had formed in Brooklyn in the late 1800s, and Bedford Stuyvesant, the Nichols’s neighborhood, had become an enclave for West Indians, nine thousand of whom resided in Brooklyn in 1920.2 Local markets carried saltfish, callaloo, and other Caribbean staples. Italians, Poles, and Jews had supplanted the Dutch and English who gave the neighborhood its name, but now Caribbean sounds emanated from the stoops that adorned the brownstone row houses. Overhearing the conversations about Kingston and Bridgetown, the hum of calypso, or a discussion of the spice buns on Nostrand Avenue, a West Indian could fool himself into believing he had never left home.3But this was New York, as the rattle of the elevated train reminded its residents. The crack of the bat Walrond heard from the street came from children playing baseball, not cricket. In one autobiographical tale, “Success Story,” young Jim Prout is newly arrived in Brooklyn. He devours a ball of coucou prepared by his aunt in the familiar Barbadian manner. But she cautions, “You must remember that in America everything is different, even sleeping.”

“Sleep?” asked Jim.

“Yes, bo. You mustn’t think you does sleep in America the same way as in the West Indies. No, bo.”

She proceeded to show him. “You must not lay down ‘pon the sheets, but betwixt them. That is the secret. And you just not forget to do that wherever you da-go. You must not let anybody think you just come” (“Success” 113).

Walrond seems to have been disoriented by the transition. In his story, Jim lapses into a gloomy reverie from which his cousin tries to rouse him.

After tramping the streets all day in search of work Jim had found the armchair by the window in Aunt Josephine’s living room, easily the most restful spot in the flat. […]

An “El” train, pulling out of the Grand Avenue Station, swung up high on to the horizon. Swiftly the view of the heavens was obliterated. As the screeching and grinding of the long curving line of coaches mounted to a crescendo Jim felt someone clap him on the shoulder. He turned just as the soft grey haze of the Northern twilight had begun to flow back into the room and saw Timothy Cumberbatch standing there beside him.

“What do you say there, fellah? I ain’t seen you in a monkey’s age. Where you been keeping yourself?”

“Hello, Timothy. I didn’t hear you come in.”

Timothy was tall, slim and black. He wore horn-rimmed glasses and a blue serge suit. He had been born in Barbados but the outward manifestations of his powers of adaptation were so impressive Jim had found it difficult to believe Timothy had spent only ten of his twenty-one years in Brooklyn.

“For crying out loud, fellah!” grinned Timothy, shaking Jim by the shoulder, “Don’t let it throw you! Buck up, boy, you ain’t down in the jungles now. You can’t git nowheres going all moony like-a so.” (160)

Marked as American through his idiom and affect, Timothy is a foil for Walrond’s character, whose adjustment is incremental and painful.

Walrond tried to get his bearings and establish himself by moving to a nearby apartment, but he struggled to find satisfying work. He entered a shorthand contest at the Stenographer’s Association, earning an honorable mention.4 He took odd jobs: “salesman—porter—dish slinger—secretary—elevator operator—editor—longshoreman—stenographer—switchboard operator—janitor—advertising solicitor—houseman—free lance” (“Godless” 32). Soon his family obligations increased, his mother and siblings arriving from Colón in September 1919. The officials who received them dutifully recorded their nationality (“British”), race (“Afn-Black”), and show money ($100). Having satisfied them that she was neither a polygamist nor an anarchist, Ruth said she intended to move her family in with her son in Brooklyn. Her husband would soon join them. Walrond now had two brothers, Claude (age 14) and Carol (7), and two sisters, Annette (17) and Eunice (4), to help look after. After a brief stint as a stenographer, he became a secretary at an architectural firm, and although the job did not last long, his supervisor was sufficiently impressed that he recommended Walrond to a friend who hired him as a clerk at the Broad Street Hospital.5 It was new but within two years had grown from a 35-bed facility to one of nine stories and more than two hundred beds.6 Walrond earned $140 per month, slightly above the median family income for New York City.

It was during this time that Walrond wrote his way into New York journalism. Within four years, he would be dining downtown with Alfred and Blanche Knopf, James Weldon Johnson, Carl Van Vechten, Zora Neale Hurston, Countée Cullen, Langston Hughes, Alain Locke, and other literati. He would take them to A’Lelia Walker’s parties, heir to the fortune of the first African American millionaire, and dance the Charleston until the early morning in the gin-soaked cabarets of Prohibition-era Harlem. It was a vertiginous ascent from which he would not soon recover.

TONGUE-TIED RAGE

Walrond recounted his difficulty finding work, attributing it to a racial prejudice that continually surprised him. In The New Republic, he wrote of having done “battle with anaemic youngsters and giggling flappers” in the employment agencies.

I am ignorantly optimistic. America is a big place; I feel it is only a question of time and perseverance. Encouraged, I go into the tall office buildings of Lower Broadway. I try every one of them. Not a firm is missed. I walk in and offer my services. I am black, foreign-looking, and a curio. My name is taken. I shall be sent for, certainly, in case of need. “Oh, don’t mention it, sir.… Glad you came in.… Good morning.” I am smiled out. I never hear from them again. (“On Being Black” 245)

An implicit code made itself felt with unerring consistency. At a Brooklyn optician, the salesman assumed he wanted the style favored by “all the colored chauffeurs.”

“But I’m not a chauffeur” I reply softly. Were it a Negro store, I might have said it with a great deal of emphasis, of vehemence. But being what it is, and knowing that the moment I raise my voice I am accused of “uppishness,” I take pains—oh such pains, to be discreet. I wanted to bellow in his ears, “Don’t think every Negro you see is a chauffeur.” (“On Being Black” 244)

The pains Walrond took to be civil—avoiding accusations of “uppishness,” refusing to “bellow”—become a recurring trope in these sketches. He gave expression to a common experience among West Indian immigrants, who were often directed into menial labor and predominantly black neighborhoods. Many suffered downward social mobility.7 When Walrond grew exasperated in print at the narrow horizon of opportunity for black New Yorkers, he was of course expressing the injustices of Jim Crow but more specifically voicing a sense of outrage among West Indian immigrants.

The key question in “Success Story” is whether Walrond’s character, Jim, will beat the odds and find work outside the service sector. He is either too ambitious or too naïve to settle for menial work. He declines a job as an elevator operator: “No, I’m sorry Timothy, I don’t know anything about running an elevator. […] I shouldn’t like to risk it. I might get stuck between floors or something.” When Timothy presses him—“You don’t seem to realize that you is in America. Don’t nobody wait for jobs in America. You goes out arter ’em and grabs ’em”—he responds, “There are lots of places I haven’t tackled yet” (163). But he will not grab if it means manual labor or joining the servant class, whom he derides as “ebony flunkeys, resplendent in blue uniforms trimmed with gold braid [who] moved with stately pomp” through the halls of Manhattan offices (162). “That guy takes the cake,” says Timothy, “Why he must be nuts to think he can get the kind of job he had in Panama in this country. Running an elevator ain’t good enough for him, huh? Well, you wait till the cold weather sets in. He will come crawling, you wait and see” (164). Thus, the question the story frames is whether the young professional will succumb to the racial logic his cousin expresses so peremptorily, whether he will assume his place as a “Negro” and accept a job he feels is beneath him.

As the title suggests, “Success Story” rejects the proposition that Walrond’s character must accede to the inexorable logic of racialization. Interviewing at one firm, he fantasizes, “If he should get the job he would give up sleeping on the bug-stained cot in Aunt Josephine’s living room and move into proper lodgings (189).” All goes well: he is hired at eighteen dollars a week, introduced as Mister Prout to the secretary, Miss Guzman, and begins training with a Venezuelan émigré. Although the position is clerical—consular invoices, bills of lading—it confers prestige and dignity. He will address secretaries in pink blouses and corduroy skirts with snappy lines, like “Step on it, Sally. I’m in a hurry,” as the Venezuelan does. His colleagues are immigrants whose backgrounds help rather than hinder their advancement, such as John Gonzaga, “son of a pushcart pedlar in Little Italy,” and Carlos Jimenez, who manages shipments to Chile (193). Jim conducts business with far-flung foreign offices, and rather than operate an elevator he rides one every morning to his nineteenth-floor office. We are meant to see that his persistence paid off, that he was not “nuts to think he can get the kind of job he had in Panama” after all. The story ends with an ironic flourish that underscores the delicate operation he has performed, persuading those in power to see beyond his blackness. His boss, reproached for having hired “a nigger in your department,” growls through his cigar, “He is not a nigger, he is a foreigner” (194). Still, the story’s ending seems bitterly ironic. In what sense is it a success that Jim circumvents this racial logic? His triumph merely illustrates the false opposition: either black or an immigrant, a “nigger” or a “foreigner.” Even after making a successful writing career, Walrond remained militant on this subject.8 He anticipated what scholars would later observe about the force of racialization and the strategies West Indians developed to negotiate it.

A tacit but unwavering prejudice among white editors forestalled his entry into New York journalism. “Young, black—the city rolling above me—I was seized by the sober aspect of work,” he wrote in a 1926 essay, “New York! America! Very logically, the newspapers dominated my vision” (“Adventures” 110). He tried “freely and spontaneously” at several papers, which is to say unencumbered by race consciousness. At one newspaper, a receptionist “became so inflamed at the colossal audacity of me that she did not feel the need to conceal outwardly the horror which seared her. ‘Why no!’ she cried, ‘there are no vacancies here—and you can’t see the city editor’” (“Adventures” 110). Trying another, his luck appeared to improve. The managing editor “bristled with the emotion of an idea. I was the very man for it!” But the offer turned out to be just as insulting, writing captions for a comic strip about “cullud folks.”

I examined some of it. It was neither truthful nor realistic, but like most comic strips, broad, lewd, and vulgar. […] The managing editor said it would bring the “cullud folks” galloping to the paper if these strips had nice peppy darky titles to them. Would I not like to do them? All I would be required to do was go through the “black belt”—the pool rooms, honky tonks, cabarets, and court rooms—and dig up the stuff. (“Adventures” 110)

He considered accepting, but in an “unconscious fury, my instincts began to quake and with a feeling of self-righteousness I failed to return with samples of the stuff.” All the rejection and misdirection left him livid, “the salt of the tropic sea ravaging the blood in my veins.” Finally, “adrift on an angry sea,” he was reduced to writing “two disgusting darky stories” for a popular magazine. An important tension had emerged in Walrond’s career: anger and disbelief, on one hand, at the white establishment’s refusal to see past his color, and adaptation, on the other, to the codes that compelled him to perform blackness in print. Negotiating this tension became vital to Walrond’s career. For the moment, he complied with “disgusting darky stories,” but alternate performances became available. As the extraordinary pressure that flattened intraracial differences became clear, he would devise strategies to manipulate the codes of representation.

But why was Walrond so struck by segregation and prejudice? After all, he spent his adolescence in Panama, where “the race problem, as it is known and understood in the United States, was first introduced on a large scale into the Caribbean.”9 Given his prior exposure, what should be made of his self-presentation as a credulous greenhorn, naïve to the ways of racial discrimination? What appears to be a faithful record of his struggle with racism may also be understood as a rhetorical device. It is not that he fabricated his distress or that his humiliations were baseless, but in depicting the experience he adopted a persona: the innocent who “doesn’t know any better,” assumes the best of white folks, and believes merit will prevail. This was a powerful rhetorical choice, making a virtue of guilelessness. Winston James notes how “ignorance of the racial mores of the society, naiveté, can sometimes redound to the benefit of the ignorant and the foolhardy.”10

Black people from the South who had come to New York during the Great Migration, were, perforce, fully aware of the racial codes and, therefore, would not as readily have taken the risk of violating those codes by knocking down the Jim Crow sign and marching into a factory demanding employment. It took “over-confident,” “aggressive,” “arrogant” […] foreigners to do that sort of thing. Black people who knew better would have kept away from the place. But by the same token, people who knew better would not have gained jobs in the trades. Ignorance is, at times, a blessing.11

Walrond employed the trope of the disillusioned greenhorn to enlist his reader’s identification and outrage, not only on behalf of West Indians suffering downward social mobility but any “Negro” whose professional qualifications were disregarded.

Walrond’s first Opportunity sketch was about his experience as a hotel “houseman” and, like much of his early work, a litany of vituperative exchanges forms a pattern of mistreatment.

Up to 301 the elevator shot me. On the door I rapt.

“Who is it?”

“Houseman.”

“Come back in about an hour. I’m not ready for you yet.”

I went to 303. I swept and dusted and mopt and scrubbed and threw at times a misty eye at the poet at the sun-baked window, tugging at his unruly brain. Surreptitiously I sipt of the atmospheric wine. At least he would let me stay—and live. So unlike that other place on the top floor where I had forgot my pail. I went back for it. The lady […] on opening the door and depriving me of the aesthetic privilege of at least hearing her voice, poised on the threshold like an icily petrified thing—and pointed Joan-of-Arc like fingers at it—my pail—nestling under the writing table. Audibly, loudly her fingers articulated, “There it is! Come and get it—you coon!”

In bewilderment I groped my way back to earth—and reason. (“On Being a Domestic” 234)

On returning to clean Room 301 he finds its occupant “cross, crimson, belligerent.” “I’m going out for lunch now,” she sniffs, “and I won’t be back for an hour, so you’ll have plenty of time to clean up. I don’t want to be alone in the room with you while you’re cleaning up.” As in many sketches, Walrond’s disorientation and injury prevent him from making a rejoinder.

I am tongue-tied. I drop the broom and the pail and out of eyes white with the dust of emotion, watch the figure chastely going down the steps. Aeons of time creep by me. It is years before I come to. But when I do it is with gargantuan violence. There rises up within me, drowning all sense of reason and pacification, a passionate feeling of revolt—revolt against domestic service—against that damnable social heirloom of my race. (234)

The repressed rejoinder is again the key trope. His inchoate fury begins as disoriented silence and transmutes into something violent, passionate. He describes a similar encounter with a clerk who refuses, because of race, to give him the advertised price of a ticket. “I am not truculent. Everything I strive to say softly, unoffensively—especially when in the midst of a color ordeal.” Managing the anger from such confrontations becomes the black person’s principal challenge, he suggests. “I am out on the street again. From across the Hudson a gurgling wind brings dust to my nostrils. I am limp, static, emotionless” (“On Being Black” 146).

Thus, Walrond’s early writing about racism represents two kinds of violence. It conveys the absurdity of qualified candidates systematically passed over. It also meditates on the psychological effects of routine racial slurs and relegation to service. “It is low, mean, degrading—this domestic serving. It thrives on chicanery. By its eternal spirit-wounds, it is responsible for the Negro’s enigmatic character. It dams up his fountains of feeling and expression. It is always a question of showering on him fistfuls of sweets, nothings, tips” (“On Being a Domestic” 234). The repressed rejoinder, damming up feeling and expression—this is Walrond’s figure for the damage of casual racism. It constitutes racism’s affective dimension, its manifestation in grief rather than grievance. In this sense, Walrond anticipated James Baldwin’s account of “the rage of the disesteemed,” a sensation he called “personally fruitless, but also absolutely inevitable.”

Rage can only with difficulty, and never entirely, be brought under the domination of the intelligence and is therefore not susceptible to any arguments whatever.… Also, rage cannot be hidden, it can only be dissembled. This dissembling deludes the thoughtless, and strengthens rage and adds, to rage, contempt. There are, no doubt, as many ways of coping with the resulting complex of tensions as there are black men in the world, but no black man can hope ever to be entirely liberated from this internal warfare.12

What Baldwin is really describing are the material effects of affect, for he adds, “This rage, so generally discounted, so little understood even among the people whose daily bread it is, is one of the things that makes history.” This is a more radical claim than it appears, and it is crucial to understanding Walrond’s life and work. One tends to think of history-making rage as articulate, politicized. Baldwin says something different. He is describing an affective register—the coping strategies of those who may not realize they are coping—and translating these into material effects, unspectacular but profoundly significant. This is the turn Walrond made during his early New York years, away from a sense of history as constituted by political forces to a poetics and politics of affect, a genealogy of rage.

For this reason, Countée Cullen dedicated “Incident,” one of his most celebrated poems, to Walrond. Exhibiting Cullen’s signature economy of expression, it recalls a distressing moment from the speaker’s youth. The poem is often read as a condemnation of racism, specifically its corrosive effect on young people. It is about the ease with which a white boy hurls the epithet “nigger” and its impact on the speaker. But it is as much about the aftereffects as the incident. Despite having stayed eight months in Baltimore, the speaker only remembers having been called “nigger.” The poem is not only about hateful speech, in other words, it is about the affective dimension, how the slur punctures and drains his memory. Cullen’s dedication acknowledged his friend’s effort to articulate these ineffable matters. Just as Cullen’s incident constitutes “all that I remember” about Baltimore, so Walrond depicted casual prejudice as generating an unforgettable rage—unforgettable because unutterable, its repression formed the contours of what he called “the Negro’s enigmatic character.”

MARRIAGE

In 1920, Walrond moved to an apartment at the corner of 137th Street and Seventh Avenue, the heart of Harlem. With two hundred thousand “Negro” residents in two square miles, in less than fifteen years, it had become the most densely populated black community on earth and a “Mecca for the sightseer, the pleasure-seeker, the curious, the adventurous, the enterprising, the ambitious, and the talented of the entire Negro world.”13 But Walrond’s connection to Brooklyn was alive and well. His fiancée, Edith Cadogan, was a Jamaican who, prior to their wedding in November 1920, lived a few blocks from him in Bedford Stuyvesant. The ceremony took place at Walrond’s Harlem apartment with his parents and Edith’s mother as witnesses. Eric was twenty-one, Edith nineteen and possibly pregnant with the first of their daughters. Two more daughters followed in as many years, but the marriage was short-lived: Edith, pregnant with Lucille, boarded a ship to Kingston in 1923 with their daughters Jean and Dorothy.

An unpublished autobiographical novel entitled Brine, begun for Walrond’s “Technique of the Novel” course at Columbia University, sheds light on the relationship.14 As in “Success Story,” his surrogate is named Jim, and the novel excerpt follows the couple on the emotional day on which he put his two infant children and his pregnant wife on a ship to Kingston. It is a disheartening tale, carefully composed but withering in its depiction of marital discord. Edith’s character, Nora, is dependent, pliant, a willing target for Jim’s verbal abuse; she is forever sobbing, her frame shaking. Jim is sullen and unsympathetic, though Walrond makes him three-dimensional, unlike Nora. Begun in 1924, Brine was Walrond’s effort to make sense of his marriage’s failure, perhaps to assuage his guilt after his family left. The opening scene establishes the conflict between the couple, though beyond a vague suggestion that Jim feels henpecked, the source of the conflict is unclear. Although Jim seems fond of his children, calling one a “cherub” and comparing the other to “a bed of yellow tulips,” he does not engage them. He displays only aggravation, and “Nora hadn’t had time in her strenuous life in America as a married woman to know her husband that well” (2). Perpetually cross, Jim replies to few of Nora’s entreaties, spitting his answers.

Within this melodramatic account, however, Walrond’s painterly sensibility also reveals itself, a quality that soon distinguished him among his peers.

Facing the pier there stretched a queue of trucks, swollen to the ribs, waiting for the signal from the gateman before they bolted in. The drivers, white men with faces black and limned with dust and dirt of rain and sun, snow and hail, toil and murk; horses and mules ridden with the brunt of age and suffering; the tarpaulins shielding the rich, unwieldy cargoes. […] Wharf hands swarmed about the mouth of the pier. Their lips red and greasy with victuals they were clad in overalls and dungarees, and were smoking and carrying on hilariously. One of them, a prizefighter, with sunken, scarlet eyes and large, high, swollen cheekbones, was shadow boxing. (5)

Such tableaux propelled Walrond’s later success in fiction, even as he struggled with exposition. The chapter ends with Jim telling an Irishman patrolling the pier, “wife’s sick; sent her ’way for a change. She’ll be back in a little while.” But he never saw her again.

The pier may have evoked the memory of the more joyful departure of another ship bound for the West Indies a few years earlier, one he almost certainly witnessed. William Ferris recalled it in messianic terms.

On a Sunday in the latter part of November, 1919, we stood on a pile of logs and watched hundreds of people jump up and down, throw hats and handkerchiefs and cheer while the Yarmouth, the first steamship of the Black Star Line, backed from the wharf at West 135th Street and slowly glided down the North River. It was sturdily built, but it was not a large, speedy, modern-equipped boat. But the news that black men had actually purchased a steamship, manned by a Negro captain and crew and sent her out into the briny deep electrified the Negro peoples of the world as no other event since the Emancipation Proclamation of Abraham Lincoln did. […] A commercial venture ended as an uplift of the spirit. It was sown a natural body, it was raised a spiritual body. And that was something of a miracle.15

Garvey would declare of this occasion:

“The Eternal has happened. For centuries the black man has been taught by his ancient overlords that he was ‘nothing,’ is ‘nothing,’ and shall never be ‘anything’.… Five years ago the Negro […] was sleeping upon his bale of cotton in the South of America; he was steeped in mud in the banana fields of the West Indies and Central America, seeing no possible way of extricating himself from the environments; he smarted under the lash of the new taskmaster in Africa; but alas! Today he is the new man.”16

GARVEYISM AND NEGRO WORLD

Based in Harlem but originally from Jamaica, Marcus Garvey inspired millennial pronouncements of the kind William Ferris expressed. In his organization’s principles and in his very bearing, he advocated dignity and self-respect for people of African descent. That link to a place derided by white supremacist cultures across the diaspora was critical to Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) principles. Not only was there nothing inferior about Africanness, Garvey countered, but a rich history of African accomplishment had been obscured by the contemporary racial hierarchy. The control exercised by people of European descent over world affairs was neither inevitable nor irreversible, he maintained. “Why should we be discouraged because somebody laughs at us today? We see and have changes every day, so pray, work, be steadfast, and be not dismayed.”17 Through self-discipline, pride, self-determination, and unstinting resistance to white supremacy, African-descended people could revive their noble past in modernity, establishing a “Negro Empire” on the ashes of those subjugating them. Unlike the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which advocated integration, the UNIA pursued “Negro” enterprises and institutions, including the “Back to Africa” colonization plan and the Black Star shipping line. Resplendent in martial attire, Garvey and the UNIA burst on the New York scene in 1917 as World War I ended. African American soldiers returned from fighting for democracy to a country riven by segregation, and nation building was the political order of the day. By 1920, the UNIA had a devoted membership in the United States and the Caribbean and held its annual convention that year in Madison Square Garden.

It has been alleged that Walrond “turned to the radical black nationalism” of Garvey out of “anger and frustration” with his poor job prospects.18 But the relationship among Walrond’s anger, political militancy, and employment by the UNIA is far more interesting. A common misconception is that Garvey, a charlatan and demagogue, was only able to dupe the witless, the white hating, and the West Indian. To be sure, Garvey was imperious, suspicious to the point of paranoia, and ruthless in his persecution of detractors. His indictment on mail fraud charges and subsequent deportation vindicated his critics and cast an ignominious pall over his legacy. But he built the largest mass movement among people of African descent to date. If he was a charlatan, there was something extraordinarily compelling in his call for racial pride, his intransigence, and his international campaign. Observers often claim that the UNIA’s broad appeal indicates how bitter even northern blacks had become, but what is missed by emphasizing bitterness and resentment is the utopian desire for autonomy and self-respect, a balm for the psychic wounds modernity had inflicted on people of African descent.19 Garvey’s notorious African colonization scheme expressed a keenly felt desire to secure a place New World blacks could call their own. If the prospect of a new African empire populated by a reversal of the baleful Middle Passage seems fanciful today, the UNIA’s ascendance reflected a widespread longing for relief from New World racism.

The “Red Summer” of 1919 punctuated this history and enhanced Garvey’s appeal. This was the “summer when the stoutest-hearted Negroes felt terror and dismay,” wrote James Weldon Johnson, when the Klan flourished and race riots erupted in Chicago, Omaha, Texas, and the nation’s capital, where “an anti-Negro mob held sway for three days, six persons were killed, and scores severely beaten.”20 An irate Claude McKay penned his famous sonnet exhorting, “If we must die—oh, let us nobly die/So that our precious blood shall not be shed/In vain.” Johnson, who was generally critical of Garvey, conceded, “He had energy and daring and the Napoleonic personality, the personality that draws masses of followers. He stirred the imagination of the Negro masses as no Negro ever had.”21 It is not hard to imagine why an ambitious black journalist such as Walrond affiliated with the UNIA. Beyond the bombast of its leader lay an organization of active adherents in pursuit of a bold collective purpose. Working at its journal, Negro World, were two of the finest minds in black America: William Ferris, who earned degrees from Yale and Harvard, and Hubert Harrison, a self-taught polymath known as the “Black Socrates.” Walrond’s UNIA journalism cannot be attributed to his susceptibility to the blandishments of a demagogue, the residual nationalism of a West Indian expatriate, or to the mercenary impulse of a writer in need of a byline. Nor is it the case that West Indian immigrants such as Walrond were politically conservative prior to their arrival and only radicalized by confrontations with U.S. racism. The virulence of prejudice in post-war America made the UNIA appealing, but the West Indians who swelled its ranks had not, by and large, been a quiet lot of Tories back home.22

When Walrond started as associate editor for the Garveyite newspaper, The Weekly Review, in December 1919, it was not his first encounter with the UNIA. Although New York became the hub of Garvey’s activity, he started the UNIA in Jamaica, and the organization’s principles were drawn from his experience there and in Costa Rica, Cuba, and Panama. In Panama, Walrond knew at least two people, Amy Ashwood and W. C. Parker, who were close to Garvey, and he was aware of the UNIA-led unionization drives among “silver” workers, prompting Isthmian Canal Commission crackdowns and strikes.23 Walrond’s departure preceded the largest of these, but the UNIA was well under way during his tenure at the Star & Herald.24 During this period, notes Colin Grant, “The traffic between Harlem and the Caribbean and the West Indian enclaves in Costa Rica and Panama was non-stop.” In fact, Walrond’s tutor W. C. Parker facilitated.

It was through the advocacy of men such as the Panamanian-based teacher Mr. Parker that word of Garvey’s movement spread […]. Garvey [also] relied on the willingness of merchant seamen to act as informal agents for the Negro World, carrying bundles of the paper from port to port. By such means the Negro World had been successfully distributed throughout the Panama Canal zone.25

Covering “commerce, politics, news, industry, and economics,” the New York–based Weekly Review was short-lived, but an excerpt from the first issue suggests its fervent anti-colonialism:

[W]e must make it unprofitable for England to hold her colonies. At the same time we must embarrass her by political agitation and propaganda in foreign countries. In our upward struggle we cannot afford to let any nation or race stand in our paths, and no nation stands so much in our path today as England. Therefore, we must do all in our power to discredit her, disrupt her empire and attain our ends at all costs. And it is not so difficult an attainment as some think.26

Sentiments like these were enough to get the attention of British intelligence officials during Walrond’s tenure as associate editor.27 They also indicate the UNIA’s departure from narrow nationalism. Walrond’s experience at the Star & Herald and The Weekly Review surely recommended him to Negro World. The journal was barely two years old when he was hired, but its circulation soon rose dramatically and it became a platform for the era’s most controversial movement.28

Within a few weeks of his first contribution in December 1921, Walrond won first prize in the journal’s literary competition, and the following week he was on the masthead as assistant editor. He was soon promoted to associate editor, and his contributions appeared regularly throughout 1922.29 These were turbulent years in the organization, in Harlem, and in Walrond’s life. He would leave Negro World almost as abruptly as he arrived, accepting a demotion in the spring of 1923 and dissolving all ties to the UNIA that summer. Walrond and Garvey would eventually find one another again in London in 1935 on better terms, but their reconciliation could not have been predicted from their falling out.

Among those who have attended to this stage of Walrond’s career, one has condemned him as the worst sort of opportunist, a traitor who deserted the cause in the time of its leader’s greatest need; another dismisses the Negro World writing as “apprentice work [that] consisted of romantic effusions and naïve hero-worship—hardly the stuff of which tough minded journalists are made.”30 It is true that his Negro World material—essays, reviews, and short fiction—is unseasoned work and bears the stamp of its ideological constraints, but a great deal is missed by assessing it strictly in terms of literary quality or fidelity to Garveyism. Walrond was negotiating in print his relationship to UNIA doctrine. On one hand, he chronicled the achievements of black people in order to promote self-esteem and group solidarity; on the other hand, he routinely ran afoul of Garveyite principles and risked alternatives. He was experimenting with voices, including but not limited to the strident assertion Garvey expected, and he put to the test his considerable appetite for polemics. Key tensions that inspired and shaped Walrond’s later work appear in incipient form in the Negro World material.

Walrond leapt into the fray with the three articles preceding his prize-winning story and staff appointment. As was expected of fledgling contributors, he trained his sights on rival movements, inveighing against Socialists and the NAACP. In “The Failure of the Pan-African Congress” in late 1921, he admonished W. E. B. Du Bois for courting white support. Du Bois and his NAACP colleagues were regular targets of UNIA vitriol. Garveyites such as Walrond cast themselves in opposition as an authentically black organization with a definitive program. The war of words flew in both directions, characterized as often by ad hominem attacks on the class and color of the adversary as by differences of opinion or strategy. Beyond the NAACP, the UNIA battled for the hearts and minds of African Americans with the Socialists and Communists, who also enjoyed black support and leadership from Cyril Briggs, Richard B. Moore, A. Philip Randolph, and Chandler Owen. Hubert Harrison was a renowned Socialist speaker before joining the UNIA, and Claude McKay worked for Communist journals in London and New York before traveling in 1922 to Moscow for the Third Communist International. If the NAACP was considered dangerous because of its elitism and ties to white America, Socialists and Communists were taken to task for being insufficiently race conscious. Walrond played the UNIA rivals against each other in late 1921 in “Between Two Mountains,” calling Du Bois “the sphinx of Fifth Avenue,” a “sneering god of intellect” who “folds his white gloved hands and gazes at the sublime prospect of life in a warless world,” while the “dyed-in-the-wool Leninists” “wave a blood-red flag” but are merely “parading their intelligence” (4). This last point was an implicit defense of Garvey, who was impugned for being uneducated and courting the ignorant masses.31

Despite some lively turns of phrase, these first Negro World essays were fairly scripted. Less predictable was his next effort, “Discouraging the Negro,” which exhibited Walrond’s familiarity with the Caribbean and the UNIA’s internationalism. The editor of The Paramaribo Times (Dutch Guiana) had castigated Garvey’s anticolonialism as “vicious and dangerous,” destined to “end in disaster and ruin.” He warned “the black people of the world” not to “forget the benefits they have enjoyed and still are enjoying under the rulers to whom they owe allegiance” (4). Discerning an apologist for colonialism, Walrond reproved the editor, calling his remarks “typical of colonial propaganda to keep the Negro ‘feeling right,’” another instance of the “crocodile sincerity” that persuaded colonial subjects of their “good fortune to be governed by the best, most humane government in the world” (4). Moreover, he added, the horrors of American racism were always trotted out to claim the relative benevolence of colonial rule. But the only difference between Americans and Europeans, he wrote, “is that the latter are veritable past masters in the art of smiling in a man’s face and at the same time sticking a dagger in his side, whereas the former are frank and less hypocritical in their domination of the Negro.” Thus, to secure “a square deal to the Negro peoples the world over,” he concluded, “a mighty republic must spring up on the shores of Africa. Only by the realization of this ideal can we hope to abolish slavery in the Congo, peonage in Hayti, and lynching in Texas” (4).

In an article about the white American novelist T. S. Stribling, Walrond again drew on his Caribbean background to engage questions of racial representation. Stribling praised Trinidadian women in the Saturday Evening Post for raising a generation of black professionals. Amplifying Stribling’s contention, Walrond said the story of the “Negro mother’s heroic part in the evolution of the race” had yet to be written. “One of these days a Negro Dickens will come along and, in his realist sweep, take in the whole panorama of irony, tragedy, heroism, sacrifice and achievement, and then the women of the race will come into their own” (4). His remarks indicate his faith in the difference a novel could make and his feelings about his own Caribbean mother. “I owe everything to the encouragement of my mother and her determination, a determination that just won’t down,” he wrote a year later (“Godless” 33).

Walrond won first prize in Negro World’s annual literary competition in December 1921 with a bit of fanciful fiction, and it is easy to see why. “A Senator’s Memoirs” featured Garvey as its hero, “the prince of men.” Set twenty years hence, the story’s conceit is that the UNIA has triumphed over adversity and established a sovereign black state capable of competing with Europe and North America culturally, economically, and militarily. It projects readers into an idyllic future in which the narrator, a senator from the Congo, marvels at the UNIA’s success, framed as the realization of God’s will.

Thanks to Jehovah, I am a free man—free to traverse the surface of the earth—free to stop and dine at any hostelry I wish—free! As I sit here and dash off these notes I cannot but think it all a massive dream. Twenty years ago, as a stranded emigrant on the shores of Egypt, if I had been told that I’d be out here, on my own estate, drinking of the transcendent beauty of the Congo, a master of my people, to be honored and respected, I’d have discounted it as an overworking of the imagination. (6)

As the senator explains, the race’s “fate and future” are glorious. Celebrating ten years of independence, “myriad brown-faced people” gathered in an expansive Liberty Square, “a huge park” named after Harlem’s UNIA headquarters. “From the banks of the Zambesi, from across the Nile, from South Africa, Liberia, Hayti, America—they stood, a free and redeemed people!” (6). The sketch turns from the senator’s reminiscence to a projection of Garvey himself, “a little man in a white tunic” who takes the podium to “a chorus of deafening cheers.” Walrond’s Garvey, president of “Africa Redeemed,” delivers a speech like those he delivered throughout the early 1920s but with the utopian ideals now fulfilled. Clumsily executed, “A Senator’s Memoirs” is a transparent attempt to demonstrate the writer’s fidelity to the cause and leader, but it is also a clever thought experiment, suspending the material conditions of the present.

As Walrond continued at Negro World, he sought to discredit stereotypes and celebrate black achievement, but he grew increasingly interested in literary matters. Over the next year, he wrote a series of prose poems, sketches, and reviews that engaged the issues of aesthetics and politics increasingly occupying the New Negro movement. Elements of Walrond’s later fiction appear here—an alertness to standard and nonstandard language use, a concern with aesthetics, and a struggle to reconcile what were thought to be the conflicting demands of art and politics. Students of African American literature will recognize these as familiar questions, but at no previous point and few since did they possess the urgency of the 1920s. Walrond’s Negro World meditations may be understood in relation to the debates about representation that intensified over the decade, punctuated by polemics such as Langston Hughes’s “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” George Schuyler’s “Negro Art Hokum,” W. E. B. Du Bois’s “Criteria of Negro Art,” and Zora Neale Hurston’s “Characteristics of Negro Expression.” Walrond was among those engaging these questions in print and at salons and forums. In fact, his interest in aesthetic matters isolated him at Negro World, which became hostile toward the arts.

“Art and Propaganda,” the terms around which much contemporary debate was waged, furnished the title for an article Walrond wrote in December 1921. The Martinican writer René Maran had been awarded the Prix Goncourt, the prestigious French literary prize, for his novel Batouala. It caused a stir because he was the first “Negro” winner, and the novel posed a critique of French colonialism in Africa.32 Among those scoffing at the selection was Ernest Boyd, editor of the Literary Review, whom Walrond proceeded to excoriate. Walrond marked out a position on the relationship between aesthetics and politics that would be taken up by proponents of New Negro literature. Ironically, it was a position from which Walrond himself would soon retreat. The lines along which Walrond assailed Maran’s detractors were not explicitly racial, but his impatience with the inherited presuppositions of European forms was evident. He conveyed his impatience with his signature wit and linguistic verve.

Tied to the conventions of literature, Boyd found too many African words in the book; it is replete with crotchets and quavers and demi semi-quavers. […] Also, he sniffs at the introduction to the work, which is a carping, merciless indictment of the brutal colonial system of France. As far as Mr. Boyd can see, what on earth has all this to do with a work of art, a penetrating study of a savage chieftain?

Shifting the discussion closer to home, Walrond compared Boyd’s “sniffs” to recent observations made by James Weldon Johnson, NAACP Secretary. In advocating that African Americans write literature free of propaganda, Johnson had misunderstood the basis from which that literature necessarily springs.

Mr. Johnson tells us there is a tendency on the part of Negro poets to be propagandic. For this reason it is going to be very difficult for the American Negro poet to create a lasting work of art. He must first purge himself of the feelings and sufferings and emotions of an outraged being, and think and write along colorless, sectionless lines. Hate, rancor, vituperation—all of these things he must cleanse himself of. But is this possible? The Negro, for centuries to come, will never be able to divorce himself from the feeling that he has not had a square deal from the rest of mankind. His music is a piercing, yelping cry against his cruel enslavement. What little he has accomplished in the field of literature is confined to the life he knows best—the life of the underdog in revolt. So far he has ignored the most potent form of literary expression, the form that brought Maran the Goncourt award. When he does take it up, it is not going to be in any half-hearted, wishy-washy manner, but straight from the shoulder, slashing, murdering, disemboweling! (4)

These questions gained urgency in subsequent years. Can the “Negro” write from a perspective beyond race? If not, must that perspective express the frustrations of the “underdog in revolt,” or is “Negro” experience more expansive?

Another rejoinder to a well-known white journalist followed, as Walrond challenged Heywood Broun of the New York World over the use of the word “nigger.” Broun endorsed it, arguing that it conveyed in sound and sense the “energy” of a people. “From the standpoint of language there is much to be said for ‘nigger,’” he contended. “‘Colored man’ is hopelessly ornate and ‘Negro’ is tainted with ethnology. More than that, it is a literary word. ‘Nigger’ is a live word. There is a ring to it like that of a true coin on a pavement” (4). The former sportswriter Broun located the word’s virtue in its evocative masculinity, solid where other words were “namby-pamby.” It was time for African Americans to embrace “nigger” and by claiming it transform its meaning. He conceded “the word had its origin in contempt, but acceptance itself would rob ‘Nigger’ of all its sting.” Although Walrond would soon use “Nigger” liberally in his fiction and defend others who did so, in Negro World he challenged Broun’s glorification of an epithet still freighted with pain.

Five years ago it was a common thing to speak of an Italian as a “Wop,” a Jew as a “Sheeney,” a Pole as a “Kike.” Today the Negro, to a vast portion of the American public, is yet a “Nigger.” The word is a stigma of inferiority and its users know it. Ever since its origin it was used to label the Negro as a member of an inferior race. The Russians and Poles and Lithuanians who came to America and were called “names” strenuously objected to it and the result is, being white, they have managed to grow far beyond the reaches of objectionable cognomens. But “Nigger” lingers. (4)

Walrond’s response echoed the UNIA party line: “We deprecate the use of the term ‘nigger,’” read the group’s 1920 Declaration of Rights, “and demand that the word Negro will be written with a capital N.” But his reaction reflected a broader suspicion African Americans harbored toward the self-styled white champions of their race. The “Negro vogue,” as Hughes called it, may have been preferable to indifference or hostility, but many felt that stereotypes were simply being revalued, not revised. The question was whether heightened attention from whites could be directed to the race’s advantage. During Walrond’s tenure at Negro World, New York’s biggest theatrical hit was the Miller and Lyles musical Shuffle Along, the tenor Roland Hayes and dancer Florence Mills became household names, and jazz and blues musicians gained white audiences. Uptown cabarets became destinations for pleasure-seekers eager to see the Charleston and the Black Bottom danced with “primitive” abandon, and major writers in the Greenwich Village scene produced “Negro-themed” work. It is not surprising that Walrond initially met these developments with the circumspect sneer that closes his article about Broun. “Among themselves, Harlem’s intellectuals had serious doubts about this new wave of white discovery,” notes David Levering Lewis.33 Broun might locate in “nigger” “the terrific contribution of physical energy which the Negro has made to America,” but it would be years before the more irreverent writers, such as Hurston, McKay, Wallace Thurman, Rudolph Fisher, and Walrond, felt confident using it in their own work.

After three months at Negro World, Walrond was promoted to associate editor. His attention turned, however, to matters that made him unsuited to continue there: the arts. His response to the apparent conflict between art and propaganda had been to claim that great “Negro” writing necessarily sprang from “the feeling that he has not had a square deal,” but soon he began cultivating what he called “the soul of a poet,” a lyrical sensibility at odds with orthodox Garveyism. He began to sense the limitations, professional and personal, of the life he had made in New York. His marriage was deteriorating, and he enrolled in college, left Negro World, and involved himself in the literary activities of the 135th Street branch of the public library and the National Urban League. Portents of this transition are evident in the two kinds of writing he pursued in Negro World: sentimental prose poems and tributes to black artists.

“I WISH I WERE AN ARTIST”

Walrond’s Negro World prose poems are saccharine and formulaic, but their appearance in this journal is remarkable. Garvey fashioned himself a poet, peppering his journal with paeans to manly race pride in leaden verse. Walrond’s effusions were quite different. At the time he wrote them, Negro World did not have an official policy for contributors, but the editors’ literary values were enumerated in an unsigned 1922 editorial. Contributors were advised not to send poetry “unless they are familiar with the rules of versification. Most that is sent is faulty because the authors are ignorant of the rules. Poetry is the highest form of expression, and no satisfactory impression will be got if the rules governing the expression are not understood and adhered to.”34 One need only recall that this was the moment The Waste Land, Cane, Harmonium, and Spring and All appeared to grasp Negro World’s aesthetic conservatism by contrast. Walrond split the difference by writing prose that employed poetic devices, indulging in florid metaphors and projecting as his persona a tormented poet manqué. Given the doctrinaire quality of most Negro World writing, Walrond’s accounts of ethereal encounters with his muse are jarringly lyrical and lachrymose.

“Yesterday I strode into the library and had a glimpse of her,” begins “A Black Virgin.” “Her eyelids are long—and fluttering. Entranced, I gaze, not impudently, as becomes a street urchin, but penetratingly, studying the features of this exquisite black virgin.” The speaker is almost too eager to deny the prurience of his gaze.

For a long time I sit there dreaming—dreaming—dreaming. Of what? Of the fortunes of the flower of youth? Of the curse of bringing a girl of her color into the world? Of fight, of agitation, of propaganda? No. Clearly separating my art from my propaganda, I sit and prop my chin on my palm and wish I were an artist. On my canvas I’d etch the lines of her fleeting figure. […] Her voice. I wonder what it is like? I go to her. “Will—will—you please tell me where I can find a copy of “Who’s Who in America?” I startle her. Like a hounded hare she glances at me. Shy, self-conscious, I think of my unshaven neck and my baggy trouser knees. I fumble at the buckles of my portfolio. Those eyes! I never saw anything so intensely mythical. […] “Why yes, I think there is one over there.” Her voice falls on my ear as the ripple of a running stream. Her face I love—her voice I adore. It is so young, so burdened with life and feeling. I follow the swish-swish of her skirt. I get the book and she is gone—gone out of my life! (4)

Artful skirt chasing formed the subject of half the writing published that spring by the soon-to-be-unmarried author. This writing sounded a discordant note in Negro World. Where else in UNIA literature does an author confess to feeling shy, self-conscious, and slovenly? A Garveyite wishing he were an artist instead of an agitator?

Subsequent contributions find the speaker in a similar reverie, the spell of which is broken when the female object of beauty returns his voyeuristic gaze. “A Vision” employs the gothic tropes found in Walrond’s later fiction.

I am on a high precipice at the edge of the sea. At my feet its gushing waves slash up against the mouth of a medieval cave. Out on the pearl-like waters of the Caribbean a brigantine drops anchor. It is night. A light tropical breeze tickles my lungs. The sky is scarlet. There is a fire on a sugar plantation five miles away. It does not disturb me. It only adds lustre to the night. (4)

A fire on a sugar plantation and it fails to disturb the speaker? What kind of Garveyite is this? Anywhere else in Negro World, a plantation fire signals rebellion, marronage, the demise of the buckra. Not for our speaker, for whom it merely “adds lustre to the night.” The political has been superseded by the picturesque. A liminal state of Romantic consciousness conjures his muse, “garbed in a gown of flimsy silk.” “She is dark. Her hair is long and flowing. There are chrysanthemum buds in it.” Her dance sends the speaker into a reverie that is only broken when “her eyes fly open. She sees my terrible face, and is afraid.” (4). Thus the conceit was replayed in weekly installments in the spring of 1922: the forlorn lover, the ideal of female perfection, the furtive gaze first satisfied and then subverted. “A Desert Fantasy” finds the speaker “a wanderer in a vast treeless Sahara,” another “dusky figure hovering about me,” administering to his “parched lips” and “flaming forehead” (4). The next week it was a kimono-clad girl, “a pitiful look in her virgin eyes,” caressing a rose until, “with a petulant grasp she lifts the rose to her blood red lips and crushes the very life out of it” (“Rose” 5). In another, as his muse recedes into a “paradise of clouds,” he notes “a narcissus [at] her lips, and Baudelaire under her arm” (“Geisha” 4). The tortured lament of the poet manqué!

The only justification one can imagine for such effusions in Negro World is the darkness of Walrond’s heroines, his muses. He is always careful to make them “dusky”—if not black then at least not white. All but once. “The Castle D’Or,” published in March 1922 contributed, one has to think, to his departure from Negro World. If it were not bad enough to be perpetually mooning over maidens draped in gauzy gossamer, the object of affection here was an elusive white maiden. Again approaches our “sorry looking poet,” “thin, hungry, dreamy eyed,” knocking at castle gates only to find them locked. Turning to the flower garden, “the queen, the beautiful queen of old, arose and stretched her ivory white hands out to him.” “Her nymph-like arms, soft, baby pink arms” complete the “vision of loveliness!”(6). It seems our poet has finally learned his lesson, for now merely “to gaze at the exquisite face and form was all that mattered.” The poet “threw his hat in the grass, took out his pad and pencil, and scribbled sonnets of love to her. That was all he wished” (6). The scandal was not the celebration of poetry, nor the turgid prose in which poetry was exalted (the journal was forgiving in this regard), but the speaker’s infatuation with the white queen. Consider Garvey’s position on interracial marriage: “To ignore the opposite sex of his race and intermarry with another race is to commit this crime or this sin for which he should never be pardoned by his race. […] For a Negro man to marry someone who does not look like his mother or not a member of his race is to insult his mother, insult nature and insult God who made his father.”35 At least one alert reader objected to Walrond’s transgression, declaring the tale “at variance with the aims and objects of the UNIA.” “Should a queen necessarily have ‘white hands’ or ‘pink skin’?” he asked. “O shades of white mania! Mr. Editor, you are under its hypnotic spell.”36 Walrond’s prose poems—tame doggerel in another context—were thus doubly scandalous here. They indulged in escapist fantasies of poetic melancholy and strayed from the established path of racialized desire.

Walrond was far from alone in feeling the pull of poetry in 1922, arguably the most pivotal year in the history of African American verse. McKay’s Harlem Shadows was published to acclaim; Toomer put the final touches on Cane; Georgia Douglas Johnson published Bronze; and James Weldon Johnson published The Book of American Negro Poetry, the preface to which linked race progress to the arts. The tide was shifting as The Crisis began emphasizing the arts and the Urban League founded Opportunity in 1922. The transformation prompted one budding poet, a Columbia dropout, to begin thinking in terms of a movement. Writing Alain Locke, Langston Hughes said, “You are right that we have enough talent now to begin a movement. I wish we had some gathering place for our artists—some little Greenwich Village of our own.”37 In Greenwich Village at that moment was another poet who would help realize their vision, the New York University student Countée Cullen, a Harlem product with several publications already to his name.

Walrond began writing regularly in Negro World about black artists, writers, and performers, many of whom were relatively unknown. These accounts expressed his struggle to reconcile aesthetic pleasure with pragmatic concerns and political engagement. Walrond expressed his desire to become an artist differently here than in his prose poems but no less audibly. His admiration for black artists registered in discussions of the artists Augusta Savage and Cecil Gaylord, the performers Florence Mills and Bert Williams, the poets Claude McKay and Georgia Douglas Johnson, and the novelists Vladimir Pushkin and Alexandre Dumas, whose African ancestry he celebrated.38 The thrill of bringing black artistic achievement to public view is especially evident in two articles he published in April 1922. One was a review of the Book of American Negro Poetry, the other an account of his visit to the private library of Arthur Schomburg, the donation of which later created the New York Public Library’s Research Center in Black Culture. His reviews addressed readers casually and intimately.

Not so very long ago I heard a man—one of the “stalwart intellectuals” of Harlem—say with a flare of braggadocio that he had “searched all through it” and could find nothing “new” or “distinctive” in Negro poetry; that, like Negro music, it was the victim of monotony and “oneness of beauty.” What was the man talking about? After reading James Weldon Johnson’s “Essay on the Negro’s Creative Genius,” which is a preface to the present volume, I am tempted to drop everything and collar this know-it-all apostle and bellow in his ears: “Here, read this!” (4)

It was unusual for Negro World to endorse an NAACP officer without qualification, but Johnson’s analysis of dialect and idiom struck a chord with Walrond, who was sensitive to the paternalistic representation of stock “Negro” characters. Beyond the curatorial service Johnson’s volume performed, Walrond was inspired by his engagement with the matter of language itself, which loomed larger as he fashioned himself a fiction writer.

A sense of wonder at the history of “Negro” achievement also characterized his account of Schomburg’s library. Schomburg grew up in Puerto Rico, and as a Brooklyn resident and Garvey supporter he had likely met Walrond previously. When Walrond visited Schomburg’s “unpretentious little dusty brown house on Kosciusko Street” in March 1922, his companion was another ambitious Negro World contributor, Zora Neale Hurston. A Southerner by birth, she had come to New York on a scholarship to Barnard College, where she studied with anthropologist Franz Boas and launched her legendary career. In 1922, however, she was still a novice, thirty-one passing for twenty-one. Her reputation as an exacting judge of character who did not suffer fools was already established, and Walrond was anxious that even before a figure as venerable as Schomburg she might make a scene.

The young lady in our party […] abominates what she contemptuously calls “form” and “useless ceremony.” […] As we put our feet on the hallowed ground and the warm glitter of Mr. Schomburg’s brown-black eyes shone down upon us, she gave way to a characteristic weakness—whispering—whispering out of the corner of her beautiful mouth. “Well, I declare,” stamping a petulant foot. “Why, I am flabbergasted. I expected to find a terribly austere giant who looked at me out of withering eyes. But the man is human, ponderously, overwhelmingly human, a genuine eighteen karat.” (“Visit” 6)

Hurston and Walrond were so impressed that both published accounts of the visit. Hurston called it “a marvelous collection when one considers that every volume on his extensive shelves is either by a Negro or about Negroes.”39 Concurring, Walrond said many of Schomburg’s materials “unsettled our universe”: the first book of African folklore “run off by Negro printers in Springvale, Natal, in 1868”; the slave narrative of Olaudah Equiano; a three-volume History of Hayti—in total “about 2,000 books by Negro writers, and they cover every imaginable subject under the sun.” All in the modest home of the “chief of the mailing department of the Bankers Trust Company” (“Visit” 6).

For Hurston and Walrond, the trip challenged the conventional wisdom about black inferiority and white civilization. More importantly, the voracious genealogical impulse behind Schomburg’s undertaking, the very mode of education his collection embodied, stood in stark contrast to the education that “Negroes” received in formal settings. Schomburg told Walrond of a great poet from his native country, a Guianese “Negro” who “attracted the attention of the world when he took first place in a prize poem contest run by Truth, a newspaper in England. Oh, that brought the world to its feet, and he became a great friend of Tennyson” (6). As useful as Schomburg’s library was for disarming opponents, Walrond also recognized its intimation of a fundamental rearticulation of history, a “counterculture of modernity,” in Paul Gilroy’s phrase.

Certainly, it offered Walrond a different view of Western civilization than he received at the College of the City of New York, where he enrolled in the fall of 1921. A short walk from the Negro World office, City College was free, and Walrond took courses in education, English, philosophy, and government. With a family, a full-time job, and a full course load in the evenings, his first semester ended with an undistinguished record. One of his instructors was Blanche Colton Williams, author of A Handbook on Story Writing and editor of that year’s O. Henry Memorial Award Prize Stories. Her convictions about the craft of fiction would have encouraged Walrond. “I not only believe that one can ‘learn to write,’” she observed, “I know, because more than once I have watched growth and tended effort from failure to success. […] Some students need only an encouraging word and sympathetic criticism.”40 Walrond took time off in 1922, and although he returned the following fall, he did not complete his three courses and never finished his degree.41 But his training undoubtedly improved his application in 1924 to study creative writing at Columbia.

Formal schooling was now only a part of Walrond’s education, which he also pursued at the 135th Street branch of the public library. Here a Book Lovers Club and an association for the Study of Negro History were convened by chief librarian Ernestine Rose, a white woman assisted by her African American colleagues Sadie Peterson, Regina Andrews, and later Nella Larsen, each of whom contributed signally to the New Negro movement. A group of Harlem-based artists and writers, the Eclectic Club, began hosting readings and public forums in early 1922 at the library and other venues. A “peripatetic group” meeting monthly, the Eclectics “provided an important forum in which poets, politicians, and patrons socialized and discussed future projects.”42 Walrond involved himself in the activity of the Eclectics, recruiting Hurston and Negro World colleagues to their events. The UNIA opened a hotel and a teashop intended as “literary forums and social centers of Harlem.”43 Located on 135th Street, “The White Peacock” was briefly “Harlem’s Greenwich Village,” said Walrond, “Musicians and flappers, students and professional people” sat amid “futurist paintings […] until far into the night talking about love and death, sculpture and literature, socialism and psychoanalysis” (“Books” 4).

At one of Walrond’s earliest Eclectic Club meetings, he was so moved by Claude McKay’s reading from Harlem Shadows that he claimed, “Every poem is a gem—there is not a mediocre one in the entire batch” (“Harlem Shadows” 4). McKay described the event as an obligation rather than a pleasure, claiming to have felt uncomfortable with his status. “I had to sit on a platform and pretend to enjoy being introduced and praised. I had to respond pleasantly. Hubert Harrison said that I owed it to my race.”

The Eclectic Club turned out in rich array to hear me: ladies and gentlemen in tenue de rigueur. I had no dress suit to wear, and so, a little nervous, I stood on the platform and humbly said my pieces. What the Eclectics thought of my poems I never heard. But what they thought of me I did. They were affronted that I did not put on a dress suit to appear before them. They thought I intended to insult their elegance because I was a radical.44

If Walrond was among those disturbed by McKay’s attire, it did not affect his review. “After swallowing these poems (as I did), one is able to appreciate why Claude McKay is idolized by lovers of the beautiful in poetry.” Yet what distinguished McKay’s work, Walrond observed, was his wedding of the beautiful to the ordinary. Concerned to identify “the life and character of the artist,” Walrond approvingly cited “Baptism,” in which the speaker enters a furnace boldly and alone, while others remain terrified without. In the galvanizing process inside Walrond discerned “the poet-artist’s philosophy”: “One may be with the mob and yet not be of it!” he concluded, a reflection on his own predicament (“Harlem Shadows” 4).

The artist’s technique, the artist’s sensibility—these became Walrond’s chief concerns. He paid tribute to black visual artists such as Augusta Savage, a sculptor who wrote poetry for Negro World. A Florida native who moved to New York to study art at Cooper Union, Savage became a central figure in the New Negro movement because of her own work and her support of others. Walrond recounted her improbable journey to art school and Harlem, where he visited her “poorly lighted room” to see her “put the finishing touches to a bust of Marcus Garvey” (3). Performing artists, too, became his subjects, and he covered two Broadway openings that exploited the popularity of Shuffle Along. Strut Miss Lizzie he panned as hackneyed vaudeville fare depicting the “Negro” as a “buffoon” and “curio.” About The Plantation Revue he was more enthusiastic, noting that it “palpitates with the spirit of Florence Mills,” whose “grace and refinement […] dominated the entire production” (“Florence”). In short, the voice Walrond developed in 1922 was not only an artist in the making—a critic of crude propagandists and champion of technique—but also a particular kind of erudition and authority. Consider what it meant for him to make claims about the quality of Broadway shows, about the ingenuity—or lack thereof—of a vaudeville performance, about the current state of sculpture and classical music, and about African American culture. It is worth recalling that he was still a young man, just 23, and less than four years removed from Panama. His training had given him journalistic practice, but much of the knowledge on which he now drew was specific to African American traditions. It is unlikely that he knew much about these subjects prior to arriving in New York. All of which suggests he was either a quick study or a good mimic.

The truth is that he was both. He was excited by the interest black New Yorkers were taking in the history and accomplishments of their race, especially insofar as this interest translated into greater self-determination, and in this excitement, he was acquiring a wealth of information. More importantly, he was fashioning himself as a diaspora intellectual who drew with equal facility on knowledge of the Caribbean and the United States. This was a challenge, but he was not the first and had models close at hand.45 If it seems unfair to call Walrond a mimic, I mean to distinguish him from those who were less interested or effective in appropriating forms of African American identity. Putting it this way emphasizes two elements of the intra-racial dynamics of black New York. The first is the critical strategy of imitation and masquerade among Caribbean immigrants. There were times at which it was advantageous to be taken for an American Negro rather than a West Indian and times when it was not. Code switching was a critical skill. The second element is the tacit assumption that in the United States “Negro” meant African American. Louis Chude-Sokei has referred to this as a form of cultural hegemony, compelling Caribbean immigrants to navigate “a cultural realm dominated by African-American writing, cultural sensibilities, and political concerns.”46 This would prove to be the most significant contribution Walrond made to the Harlem Renaissance, negotiating the unevenly articulated worlds of West Indian and African American New York and writing about it, code switching in subject matter and lexicon.

One of the great ironies of Walrond’s Harlem career is that his transition to mainstream periodicals was predicated on his knowledge of African American vernacular culture and speech. He became a preferred writer for white editors seeking an inside story on Harlem, the Great Migration, or the Charleston dance craze. What is extraordinary is not their willingness to rely on a West Indian for an “authentic Negro perspective” but the dexterity with which he executed this work while also writing about the Caribbean. The first of his articles to appear in a white periodical illustrates this point, “Developed and Undeveloped Negro Literature,” which ran in the Dearborn Independent in 1922.47 “One reason why the Negro has not made any sort of headway in fiction is due to the effects of color prejudice,” he wrote. “It is difficult for a Negro to write stories without bringing in the race question. As soon as a writer demonstrates skill along imaginative lines he is bound to succumb to the temptations of reform and propaganda” (12). The pattern of oppositions is familiar—art versus propaganda, fiction versus race writing—but his position was changing. His article about Maran and the Prix Goncourt had challenged the view that a “Negro” artist “must first purge himself of the feelings and sufferings and emotions of an outraged being, and think and write along colorless, sectionless lines.” “Is this possible?” was his rhetorical response; “Negro” fiction would of necessity express “the life of the underdog in revolt.” In the Dearborn Independent, however, he cast race consciousness as antithetical to the enterprise of fiction, an obstacle to the race’s “headway” in that field.

“Developed and Undeveloped Negro Literature” is remarkable not only for this revision of the relationship between art and society but also for the evidence Walrond cited. He based his discussion on a comparison of Paul Laurence Dunbar to Charles Chesnutt, turn-of-the-century African American writers. What Walrond admired in Dunbar was his deft anticipation of audience and his code-switching facility. “In his dialect poems, irresistible in humor and pathos, and his short stories of southern Negro life, Dunbar depicted the Negro as he is. Yet that does not mean he was not capable of classic prose. Realizing that a Negro poet is expected to sing the songs of the cotton fields in the language of the cotton fields, Dunbar wrote dialect” (12). Intentionally or not, Walrond was allegorizing his own experience, the conditions of his own article’s production. A West Indian with just a few years in New York, he was fashioning a voice and a version of authority that were deliberately chosen. He represented himself as expert in matters of African American literature and was persuasive in doing so.

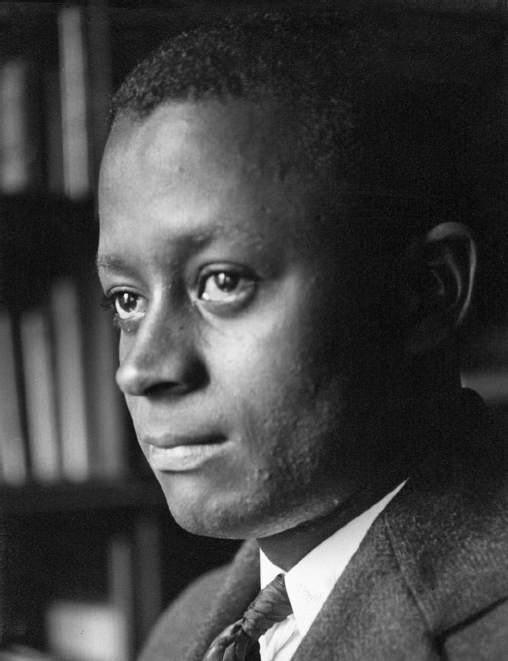

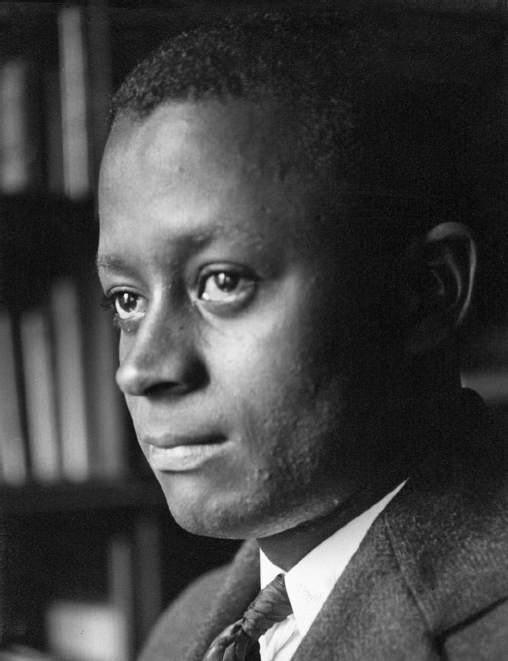

3.1 Photograph of Eric Walrond by Robert H. Davis, 1922.

Robert H. Davis Papers, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

The strategies of mimicry and masking Walrond began to develop were responses to two intersecting pressures. One was the pressure he identified with Dunbar, the expectation to conform to stereotypical modes of “Negro” expression. The other was the pressure on West Indians to become African Americans and suppress signs of intraracial difference in the process. It is not surprising, then, that one figure with whom Walrond identified was Bert Williams, the black actor whose starring roles in the Ziegfield Follies and in the musical comedy In Dahomey capped a career of minstrel performances.48 A black in blackface, Williams was assailed by progressives for pandering to white prejudices, embodying caricatures the New Negro sought to transcend. Walrond’s tribute to Williams, published a year after his death, was nominally a review of a biography, but the terms in which it praised Williams, who grew up in the Bahamas, speak to dilemmas Walrond himself confronted. For one thing, Walrond refused to see Williams as the advocates of racial uplift did, the last vestige of a shameful, self-commodifying past. Instead, he claimed him for the current generation of artists, despite their differences, situating him in modernity and extolling him as a forerunner.

To us, to whom he meant so much as an ambassador across the border of color, his memory will grow richer and more glorious as time goes on. For Bert Williams blazed the path to Broadway for the Negro actor. […] [He] bore the brunt of ridicule—of ridicule from the Negro press—and fought his noble fight. Today the results are just coming to light. The demand for Negro shows on Broadway is taking a number of Negro girls and men out of the kitchens and poolrooms and janitor service. Bert Williams’s tree—to him one of gall—is already beginning to bear fruit, and there is no telling how long the harvest will last. (“Bert Williams” 4)

Importantly, Walrond identified with Williams’s desire to remove the minstrel mask, a frustration he saw manifest in melancholia. Throughout Williams’s life “runs a poignant strain—a strain of melancholy,” he wrote, “a nostalgia of the soul—of the blackface comedian who wanted to follow in the footsteps of celebrated Negro actors like Ira Aldridge, who wanted to play ‘Othello’ and other non-comical pieces” (4). The outrage Walrond recounted at having to write two “disgusting darky stories” resonates here. So does his diagnosis of the resulting condition—melancholia—on which Walrond meditated at length.

Some day one of our budding storywriters ought to sit down and write a novel with a Negro protagonist with melancholia as the central idea. Bert Williams had it. Although it was his business to make people laugh, there were times when he would go into his shell-like cave of a mind and reflect—and fight it out. “Is it worth it?” One side of him would ask, “Is it worth it—the applause, the financial rewards, the fame? Is it really worth it—lynching one’s soul in blackface twaddle?” “But it is the only way you can break in,” protests the other side of the man. “It is the only way. That is what the white man expects of you—comedy—blackface comedy. In time, you know, they’ll learn to expect serious things from you. In time.” (4)

Staging this debate, Walrond may appear simply to offer a tears-of-the-clown platitude about the heartbreak behind a stage smile. Or perhaps we hear a reference to Dunbar’s poem “We Wear the Mask.” But it is worth emphasizing that neither Walrond nor Williams were African Americans by birth, and the question of wearing the “darky” mask is an intricate one. Louis Chude-Sokei reminds us that as a West Indian immigrant,

[Williams] was self-consciously performing not as a “black man” but as the white racist representation of an African American, which he may have phenotypically resembled, but which—as he emphasized—was also culturally other to him. This cross-cultural, intra-racial masquerade constituted a form of dialogue at a time when tensions between the multiple and distinct black groups in New York City were often seething despite various attempts at pan-African solidarity. The process by which Bert Williams learned to both be and play an African American is not only a unique narrative of modernism; it is in fact an experience of assimilation unique to non-American blacks. (5)