ou are perfectly correct about Eric Walrond,” Robert Davis told Edna Worthley Underwood, “He is quite the most promising young man I have seen in a long time.” An esteemed translator and author, Underwood had forwarded four stories to the editor of Munsey’s. Davis acknowledged Walrond’s talent but rejected the stories.

ou are perfectly correct about Eric Walrond,” Robert Davis told Edna Worthley Underwood, “He is quite the most promising young man I have seen in a long time.” An esteemed translator and author, Underwood had forwarded four stories to the editor of Munsey’s. Davis acknowledged Walrond’s talent but rejected the stories.

He has [a] genius for color; I never saw better atmosphere in anything. Of course he is violently irreverent. I can use nothing of the manuscripts enclosed. He has let down the barriers without reserve. It grieves me to let these manuscripts go back to you. In spite of which I am much concerned about his future. […] Nobody understands so well as he the people about whom he writes. I await with eagerness your consent to help. I have no doubt there are many magazines that would publish these stories without changing a syllable. However, I cannot with safety present these bald though brilliant descriptions of men and women and manners—or the lack of manners, whichever you choose.1

When they met, Davis persuaded Walrond to write two stories for his other publication, a pulp weekly, Argosy’s All Story. They were likely the “disgusting darky stories” to which Walrond referred in “Adventures in Misunderstanding.” But it was not the last effort Underwood made on his behalf, broadening his contacts beyond the black community. She was one of three people Walrond had the good fortune to impress in 1923. The others were Casper Holstein, a Harlem real estate baron, and William McFee, an English writer and ship’s engineer. Each helped redirect Walrond’s career as his disillusionment with Garveyism deepened.

Unhappy in the Garvey movement and his marriage, Walrond had deserted both in the late spring of 1923, signing on to work aboard a ship bound for the Caribbean. “I went to sea,” he said, “It is the easiest way to—to forget things” (“Godless” 33). With McFee as chief engineer and Walrond a cook’s helper, the ship made port calls from New Orleans to Cartagena. Walrond’s voyage profoundly influenced the fledgling writer’s development. The settings of several early stories are traceable to this journey, and McFee was a valuable mentor. He discussed Lafcadio Hearn and Pierre Loti as models for writing about tropical places, and he suggested Walrond acquire an agent, recommending Underwood.2 “I lived!” Walrond declared, “I saw life lived!” (“Godless” 33). Nevertheless, Underwood claimed he was disconsolate when they first met. It is difficult to trust her account, which, despite being among the fullest recollections of Walrond’s early career, is riddled with inaccuracies.

One day he phoned my secretary and asked to come out. He told me he was sad, homesick for the south, and miserable here in the north where he did not know which way to turn for the work he needed. […] He asked me to suggest something that would help him get steady work, a living of sorts, telling me that he had tried newspaper work a little both in Panama and in Harlem. […] I told him he talked unusually well and I believed if he wrote some stories of the tropic home he missed so, with all the homesick eloquence with which he related his memories to me, they might have success. But he had no place in which to write, and he had nothing to live on. Then he called up Caspar Holstein, rich man of Harlem, who had been born in the Virgin Islands and now was owner of a fleet of ships and was noted for his generosity, his unstinted help to his race. I assured him that Walrond had unusual talent and that all he needed was a little chance to unfold that talent. Holstein […] was his usual greathearted self. He offered him a place to live in his own home, provided him with a finely furnished room, and an allowance. Here young Walrond set about writing his stories—many stories—all of which I had him rewrite again and again; things of charm usually, all of them pulsing with the life of his sensitive responsive youth then at its height. He wrote diligently for months just as I had suggested, bringing the stories to me one after the other. I sent him with a letter of introduction to Bob Davis, whose judgment in the short story art has a certain amount of finality.3

Without her intervention, Underwood suggests, Walrond would have toiled away in penury and obscurity. Instead, “over-night he became famous. Praise and social honours were his, together with a secure and considerable income.” But a candid assessment reveals the significance of other factors—a 1924 Civic Club dinner at which Walrond and others met New York’s publishing establishment; his work with Charles Johnson at Opportunity; Alain Locke’s The New Negro (1925), featuring a story by Walrond; and the collection of what Underwood calls “the stories” into Tropic Death. Far from having “tried newspaper work a little,” Walrond’s journalism was a bridge to his fiction writing, a point made as early as 1928, when the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences named him among the journalists who midwifed “the birth of the so-called New Negro” in literature.4 Overstating her role as his savior, Underwood neglected the role of the community in which Walrond was immersed; she omitted the New Negro movement.

White patronage has a thorny legacy in Harlem Renaissance historiography, and Walrond’s relationship with Underwood was unconventional.5 A wealthy white woman twenty-five years his senior, she was not his social equal, but assistance did not flow in one direction alone. In Underwood’s view, African American writing infused vitality into a Western tradition that could no longer rely simply on white writers. Casting the deficiencies of Anglo-America in explicitly racial terms, she announced at the first Opportunity banquet, “Joy—its mainspring—is dying in the Great Caucasian race.”6 She was not alone in prescribing black “vitality” and “joy” as remedies for the overcivilization of Anglo-America. “The Negro” figured centrally in the critique of Anglo-America from white bohemians and other detractors of genteel values. If she saw in Walrond a glimmer of the joy “Negroes” could contribute, it may have been a projection, but it also registered her dissent from the exaltation of the “Great Caucasian race” enjoying pernicious currency at the time.

Walrond credited Underwood for encouraging him, reading drafts, and contacting friends on his behalf. She sent him an excerpt from her latest book on translation, and he sent her his “Developed and Undeveloped Negro Literature” essay. “I am also taking the liberty of sending you a short story of mine,” he added, “which, I think, is illustrative of the sort of writing I would some day like to do.”7 When Underwood offered to send his story to a fellow writer and critic, he wrote to say he was “deeply indebted.”

I think your plan is excellent, flattering to say the least, and I don’t know how to thank you for your wonderful interest and generosity. I think I’ve done about ten stories already. […] Were it not for the fact that I hate to overload you with my literary troubles, I’d put them in shape and send them to you, and if you think them worthwhile, then we could get together and see about sending them to the publisher of whom you spoke.

In the next two months Walrond wrote “The Consul’s Clerk,” “The Godless City,” “Voodoo Vengeance,” and “The Wharf Rats.” “I have tried to put my best foot forward in these stories of Panama,” he told her, “and I earnestly hope they will measure up to the standard required for admission to Mr. Bob Davis’ ‘Munsey’s.’”8

They did not measure up, but Walrond and Underwood had other irons in the fire. He introduced her to Negro World readers through his review of her novel The Penitent.9 Three consecutive issues included her translations of Alexander Pushkin’s reflections on his African ancestry. She helped him place “On Being Black” in The New Republic, where she knew the editor Robert Herrick. Much of what Walrond published the following year was facilitated by Underwood, including pieces in Current History, The Smart Set, and The International Interpreter, a highbrow weekly. This work, in conjunction with his New Republic reviews, shifted Walrond’s audience and authorial status. In the subsequent two years, his readership expanded to the New York Herald Tribune, Forbes, Vanity Fair, The Independent, Brentano’s Book Chat, and the Saturday Review of Literature. Underwood and McFee were invaluable as Walrond crossed into the mainstream, among the first African American writers of his generation to do so.

But the crossover was neither linear nor complete. Like most African American journalists who achieved a measure of mainstream success, Walrond continued to publish primarily in black periodicals. It was the black community that sustained him, even when paychecks came from elsewhere. Walrond left Negro World in the spring of 1923, but it was not a transition from black to white, as he placed work in The Crisis, The Messenger, and Opportunity, the last of which offered him a staff position. Nor do McFee and Underwood deserve all the credit; Alain Locke and Charles Johnson advocated for Walrond and his peers, launching careers that straddled the color line. Finally, Walrond’s own gift as a pitchman for his work should not be underestimated. “He made his own contacts,” said Ethel Ray Nance.

He would go out and seek editors and publishers, show them his work rather than rely on friends or agents or other people, other sources. […] He had a newsman’s sense of timing. He would know when an article should be written and what the subject should be, and he’d busy himself and write a whole evening and go downtown the next day and usually would find a market for his article.10

A point about Walrond’s transition to mainstream publications bears emphasis. Walrond’s break with Garveyism could be seen as an expression of Americanization and an increasing identification with African Americans.11 The Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), with its foreign-born officers and militant ideology, was widely understood as anti-American. Breaking with Garvey and writing for rival publications, Walrond embraced different literary values and a different cultural agenda. But the transition did not constitute a disavowal. The trappings of the greenhorn may appear to be cast off: a foreign-born social movement repudiated, a foreign-born wife returned home, an interest in the immigrant experience succeeded by an interest in African American experience. But this narrative suppresses many features of Walrond’s career as he maintained multiple affiliations, troubling a linear narrative of acculturation. Even as his expressions of Americanness became explicit and his fondness for Harlem grew, he maintained a West Indian identity, experimenting on the page with a range of voices and deepening his analysis of the African diaspora in the plural Americas.

CASPER HOLSTEIN AND CRITICAL INTERNATIONALISM

In early 1922, Negro World published an unsigned editorial condemning the U.S. government’s conduct in the Virgin Islands. Its author was one of Harlem’s Virgin Islanders. “When I was on the staff of Negro World,” Walrond recalled, “Casper Holstein came to me with an article he had written” in rejoinder to sketches T. S. Stribling had published.

Mr. Holstein, who had just returned from six months’ trip to the islands […] felt that the author of Birthright had not told the whole truth in regard to the actual labor, racial, and political conditions there. I had the “temerity” to publish the article, which was the first of a series of blows Casper Holstein struck and is still continuing to strike in defense of the manhood of the Virgin Islanders. (“Says” 1)

Walrond’s account of Holstein as an astute political actor departs from established histories that depict him as a crooked philanthropist. Holstein infamously operated the Harlem numbers racket, an underground lottery, but his shrewd political analysis and commitment to Caribbean self-determination impressed Walrond. His critique of U.S. imperialism demonstrated a racial militancy that aligned him with the UNIA.12 Conditions under U.S. occupation were not well-known, but Holstein and Harrison exposed the U.S. agenda, seeking representation for Virgin Islanders in local government and in Washington. A tidy narrative of Walrond’s conversion from Garveyite to aesthete, West Indian to American, separatist to integrationist, misses the investment he maintained in Caribbean struggles.

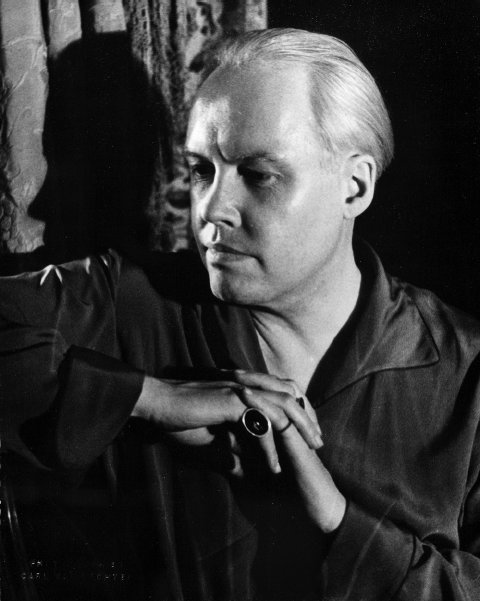

4.1 Photograph of Casper Holstein, 1926, photographer unknown.

Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Courtesy of the National Urban League, Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life.

As Walrond’s faith in Garvey wavered, Holstein inspired him. He emphasized Holstein’s modesty, implying a contrast to Garvey’s arrogance.

When it comes to spending money for a cause, to doing things for people without hoping for reward, when it comes to being the receiver of ungratefulness of the most disillusioning kind, of shouldering a burden that is growing larger and larger with the rising of each sun, you have to go to hand it to Casper Holstein. […] And, much to his credit, Casper Holstein is the poorest, the rottenest self-advertiser in the world. […] He is contemptuous of the limelight. (“Says” 1)

Holstein represented a different sort of leader, and if Walrond’s account tended toward hyperbole, it underscored his dilemma in 1922.13 Disillusioned with the UNIA, he was wary of all race leaders, not just Garvey. His friendship with Holstein developed in the context of this perceived crisis of leadership, which he discussed in Current History in 1923.

“The New Negro Faces America” excoriated Garvey, the first time Walrond did so in print. But he was no kinder to other race leaders. The article seemed at first to follow a formula: establish the urgency of the race problem, identify the deficiencies of Du Bois, Washington, and others, then recommend Garvey as the solution. But Walrond flipped the script. “The negro is at the crossroads of American life,” he began, “He is, probably more than any other group within our borders, the most vigorously ‘led.’” Garvey was preferable, he conceded, to Du Bois or Booker T. Washington’s successors. But after enumerating Garvey’s improbable success, Walrond went off-script, accusing him of “preposterous mistakes.” As a result, “a reaction set in. The crowds who once flocked to hear how he was going to redeem Africa have begun to dwindle.” The hard fact was, “the Negroes of America do not want to go back to Africa.” Africa may “mean something racial, if not spiritual” to “the thinking ones” among them, but most are indifferent to the colonization scheme, “the salient feature of Garvey’s propaganda.” “To them Africa is a dream—an unrealizable dream. In America, despite its ‘Jim-Crow’ laws, they see something beautiful” (788). Most damning of all, he called Garvey a “megalomaniac” (787). The gauntlet had been thrown down.

Where did this leave African Americans? Walrond pinned his hopes on a distributed model of progress, the gains ordinary African Americans made in the professions, industry, and the arts, not on a charismatic individual or vanguard program. He documented sharp increases in the amount and value of property owned by African Americans but argued that the truest indicator of “the outlook for the negro” was his “mental state.” In valuing disposition over data, Walrond expressed as much about his own mental state as about the “new negro” for whom he claimed to speak.

Though there are thousands of college-bred negroes working as janitors and bricklayers and railroad car porters, there are still more thousands in colleges and universities who are fitting themselves well to become architects, engineers, chemists, manufacturers. The new negro, who does not want to go back to Africa, is fondly cherishing an ideal—and that is, that the time will come when America will look upon the negro not as a savage with an inferior mentality, but as a civilized man. The American negro of today believes intensely in America. […] He is pinning everything on the hope, illusion or not, that America will someday find its soul, forget the negro’s black skin, and recognize him as one of the nation’s most loyal sons and defenders. (788)

This was a dramatic break with Garveyism, the formulation of a “new negro” sensibility drawn from his own tentative embrace of integration and cultural pluralism.

As Walrond’s reference to the “new negro” indicates, the phrase had entered the popular lexicon before Locke made it the title of his anthology.14 It had a nationalist connotation, but Walrond was among those who insisted on the term’s critical internationalism. A. Philip Randolph and Chandler Owen called the New Negro “the product of the same world wide forces that have brought into being the great liberal and radical movements that are now seizing the reins of political, economic, and social power in all of the civilized countries of the world.”15 For Walrond, the task was to represent the challenges and opportunities facing people of African descent, remaining alert to the specificity of African American experience without obscuring the common threads of the black Atlantic: relocation and enslavement, colonialism, violence and exploitation, resistance and rebellion, cultural and linguistic syncretism. His vision was no longer grounded in an immutable antagonism between white and black, the UNIA’s binary construct. The struggle of the “Negro” in Babylon yielded to an account in which ethnicity, nation, language, class, and culture constituted a field whose complexity was not apprehended by race alone. Walrond’s hope that “America will some day find its soul” and recognize the “Negro” as “one of its most loyal sons and defenders” did not prevent him from upbraiding the United States, which was engaged in neocolonial projects in the Caribbean and beyond.

In fact, in another Current History essay, Walrond argued that U.S. rule resembled the English administration of Crown Colonies and was in some ways worse for the islands’ residents. “From a strategic point of view,” Walrond wrote, “the Virgin Islands are necessary to the safety and protection of the Panama Canal and also to American interests in the Antilles” (221). But its “temporary Government” had come to resemble Haiti and the Dominican Republic, both under U.S. Navy occupation.16 Three deleterious results followed: racism was “aggravated” by the imposition of Jim Crow, local industry was undercut by Prohibition policies, and democracy was thwarted at every turn. This essay, “Autocracy in the Virgin Islands,” politicized a region North Americans associated with palm trees and azure skies. Although it resembled Walrond’s work in Negro World, the tone diverged sharply, trading incendiary rhetoric for dispassionate analysis. His approach abided by Current History’s mission, to provide “a survey of the important events of the world, told by those most competent to present them; the FACTS of today’s history impartially related, without bias, criticism, or editorial comment.” The other mainstream venue in which Walrond began publishing, The International Interpreter, professed a similar commitment to impartiality and geographic scope.17 Neither the Interpreter nor Current History indulged in special pleading on behalf of “Negroes,” about whom articles were scarce. But because of Walrond’s adept framing of race in relation to national and international matters, he succeeded in placing five investigative reports in the Interpreter in one year. Several shared the theme of migration—two on Caribbean migration to the United States, two on African American migration—while another, “Inter-Racial Cooperation in the South,” developed the proposition that mutual understanding across the color line was possible and desirable; it could be engineered to benefit the nation as a whole.

Despite the platform the Interpreter and Current History provided, their injunction for objectivity did not satisfy his political militancy or his interest in linguistic innovation and narrative form. These found expression in his final publications in Negro World, stylized accounts of conversations he had in Guatemala and Havana. Both decried race prejudice in the United States by contrasting it with amicable race relations in other parts of the world. But what stands out is the subordination of argument to characterization and atmospherics.

Along el Avenida Italia old ragged brown women smoking Ghanga weed—“it mek you smaht lek a flea”—huddled up against picturesque dwellings. Taxis filled with carnivalling crowds sped by. Foreign seamen staggered half-drunk out of Casas Francesas. Doggoning the heat, Babbitt and silk-sweatered Myra clung desperately to flasks of honest-to-goodness Bacardi. Bewitching senoritas in opera wraps of white and orange and scintillating brown stept out of gorgeous limousines.18

The ostensible focus of the essay is an encounter with an expatriate African American, an elderly man from Georgia who, after eight years in Havana, renounced the land of Jim Crow. Competing with the overt subject is Walrond’s irrepressible narrative voice, for the sketch is also about himself. “Nostalgically I dug into the bowels of the dingy callecitas. Something, I don’t know what drew me, led me on. Was it the glamour of the tropical sky, the hot, voluptuous night, the nectar of Felipe’s cebada? Or maybe the intriguing echo of Mademoiselle’s ‘Martinique! Hola, Martinique!’ as the taxi skidaddled around the corner? It was all of these and more.”19 The real subject is Walrond’s persistent romance with the Caribbean port city. However awkwardly, these sketches wed the political militancy that drew Walrond to Negro World with a romantic attachment to “the folk” and a propensity for formal experimentation that unfit him to continue there. The sketches also speak to Walrond’s ongoing concern with the varieties of black experience in Latin America. Walrond’s work in early 1923 all points to the importance of a critical internationalism in understanding race relations in the United States.

Eager to embrace New York, Walrond nevertheless remained proud of his Caribbeanness and convinced of its value to a movement that often assumed nationalist lines. He began to see the United States as the proverbial land of opportunity, evincing unprecedented enthusiasm, but his transnational sensibility was at odds with the prevailing rhetoric of race.20 With a hemispheric perspective, “Walrond understood as early as the 1920s what it meant to say that the Caribbean was, in modernity, an American sea,” notes Michelle Stephens, “The presence of the U.S. as an economic force in the Caribbean, and a political force in the world at the beginning of the twentieth century, meant a story of economic and cultural integration.”21 His effort to maintain both sides of his cultural identity—the British West Indian and the American “Negro”—is evident in his work throughout this period. One manifestation was his ambivalence about becoming a U.S. citizen; he applied for “first papers” in 1923 but never completed the process. From the perspective of literary history, however, the significant expressions of his attempt to hold Americanness and Caribbeanness in tension occur in his work. A tight-knit community sustained Walrond during this period of dawning recognition of both his extraordinary talent and his psychological fragility.

OUR LITTLE GROUP

Gwendolyn Bennett was an early friend of Walrond’s in New York, and a visual artist, poet, and prose writer. Remembered for artwork in Opportunity and The Crisis and her column “The Ebony Flute,” she also taught at Howard University and published in The New Negro and Fire!! She was raised in Bedford-Stuyvesant, where she and Walrond grew close in the early 1920s, supporting each other’s endeavors and working together at Opportunity. They were kindred spirits with immense mutual admiration. Walrond called her Gwennie and said in 1946 that she was “the closest approximation to a favourite sister I have ever had.”22 One of his first sketches for Opportunity was inspired by a scandal she and her friends provoked at Girls’ High School by integrating their prom, an event Bennett memorialized by clipping coverage from local papers.

4.2 Photograph of Gwendolyn Bennett, c. 1920, photographer unknown.

Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

Walrond wrote “Cynthia Goes to the Prom” in late 1923, illustrating a Brooklyn girl’s discovery of race consciousness. Before the prom, Cynthia never felt her color was an impediment. Blessed with “nerve,” she was popular at a school “where Irish, Jew, Italian, and Anglo-Saxon mixed,” she “always came out at or very near the top” academically, and the boys, who “first stared askance at the ebony locks that adorn her bronze temples […] before you knew it, ‘took’ completely to her” (342). When our chivalrous narrator offers to accompany her to the prom, he accidentally initiates her into the ways of white prejudice. The eight “Negroes” stay “silently composed,” frustrating the three hundred guests who “all trotted out to see what we looked like.” “Nobody stumbled over the carpet. Nobody tripped. In fact, I think I saw a look of disappointment on some of our spectators’ faces. Some of them had come for a good hearty lung-expanding laugh. But they didn’t get it” (343). A showdown ensues at the cloakroom, where the clerk “hasn’t any more hooks left,” says Cynthia, “so she says she’d have to put our coats on the floor.” “I looked at the lady in charge,” Walrond writes, “Her face barked at me. Her green eyes spat fire. She was ready to fight, to fly at our throats” (343). The same classmates whose favor Cynthia enjoys at school now snub her, and the narrator poses a loaded question at the evening’s end: “What do you think of social equality now?” “Not much,” she replies, “I tell you one thing, though—whenever I get a chance I’m going to these affairs. They’ve got to get used to us! They must!” The sketch concludes with the narrator marveling that such conviction had come from a former “disciple of passivism” (343). Walrond does not declare the futility of changing white folks’ views, as he might have earlier, he instead admires Cynthia’s resolve to pursue integration and equality. By late 1923, he had determined that the United States would be an ideal place if color were not such a universal preoccupation, not just among whites but also African Americans.

His satire of American color consciousness, “Vignettes of the Dusk,” laments that someplace so wonderful could be so afflicted with a debilitating color fixation. Set in Wall Street, “the heart of America’s financial seraglio,” the sketch has Walrond contemplating lunch at an inexpensive diner and “the most democratic eating place I know. There is no class prejudice; no discrimination; newsboys, bootblacks, factory slaves, all eat at Max’s” (19). But it is payday and he feels “flush,” entertaining romantic notions of America’s promise: “Rich, I am extravagant today. I rub elbows with bankers and millionaires and comely office girls. Of seraphs and madrigals I dream—nut that I am. I look up at the sparkling gems of architecture and marvel at the beauty that is America. America!” (19). He chooses someplace swanky, resplendent with “swinging doors and chocolate puffs in the show case,” “mirrors, flowers, paintings, candelabra; waiters in gowns as white as alabaster,” and two delicacies on the menu: oyster salad and a dessert suggestively named “vanilla temptation.” But the reverie is broken by a racial incident, something amiss when the waiter brings his order. “Couldn’t he just hand it to me over there instead of having to come all the way round the counter to make sure it gets into my hands? Couldn’t he have saved himself all that trouble?” But the waiter is not accommodating Walrond, he is ensuring that a signal of opprobrium is delivered discreetly.

He is at my side. Stern and white-lipped he hands me a nice brown paper bag with dusky flowers on it. He holds it off with the tips of his fingers as if its contents were leprous. “Careful,” he warns farsightedly, “else you’ll spill the temptation.” I do not argue. Sepulchrally I pay the check and waltz out. It is the equivalent of being shooed out. And, listen folks, he was careful not to say, “No, we don’t serve no colored here.” (19)

If this were its only episode, “Vignettes of the Dusk” would resemble Walrond’s early journalism: fulminating against racial slights, denials of the “vanilla temptation.” But it is distinguished by its celebration of American promise, opportunity qualified only by its fixation with color.

With mainstream publications, Walrond found his reputation enhanced and began thinking of himself in 1923 as a writer of real promise. This affirmation was nourished by his association with the 135th Street public library. Bennett saved a report of one event in which they shared space on the bill. Entitled “Poet’s Evening: A Real Library Treat,” the article conveys the frisson of a movement emerging from its chrysalis.23 And although Bennett had her own reasons for saving the article—it said she stole the show—Walrond memorialized the evening differently. Employing the sardonic voice he adopted to cover the Van Doren lecture, his article bore a portentous, defensive title, “My Version of It.” “‘Of what?’ you ask, bewildered. Of the to-do at the young writers’ evening at the library Wednesday night” (4). Audience members objected to his risqué treatment of women.

After the poets […] got through with their “poetical effusions”—Arthur Schomburg’s words—it devolved on us to read a story of Negro life. In the first place, the title had a tendency to prejudice those who heard it against the author. “Woman.” Woman, woman, woman—Well, for the first two pages it went off all right. Then, tip-toeing, one, two, three ladies crept out. On we read. In turning a page we caught Dorothy Friedman’s violet eyes. “Louder,” her lips pantomimed; “I can’t hear you.” On we read. On, on, on … Until the end came. Arthur Schomburg, at the behest of the chairlady, was the first to illude us. “I didn’t know that fellow Walrond had such a keen pair of eyes. Now, the point about the purple chemise—”The point about the purple chemise is the point they won’t let us print. (4)

The grumbling that ensued was audible, prompting the chief librarian to come to his defense.

In the breaking up of the crowd we got a glimpse of the way they reacted to “Woman.” “Is he really as bad as all that, Miss Rose?”

“I don’t think so,” Miss Rose responded spiritedly.

“Well,” she condescended to come over to us, “Well, I enjoyed yours too.”

“Shake!” cried Joe Gould. “I’ll buy you a cup of black coffee, so help me! I sure envy you your courage.”

“And to think—that ending—wasn’t it awful? And there was a minister in the audience besides! Wasn’t that terrible—to think—to think—”

“Lewd! Licentious! Full of passion! Terrible!”

“And that ending! My gawd! I almost blushed!”

“I don’t know what’s come over our men. Story about white men and colored women—and white men in the audience! Didn’t you see how that white man turned and whispered to the girl with him?” (4)

As the article chronicles his contentious reception, it engages in a peculiar sort of performance, reveling in the terms in which the audience applauded or clucked. It celebrates his self-fashioning as someone willing to offend moralistic listeners.

This posture of irreverence aligned Walrond with those who would soon mount the short-lived journal Fire!! They frankly addressed sexuality, interracial relationships, and vulgarity, matters that were still taboo among those anxious to improve white opinion of African Americans. Walrond saw a new generation resisting this “vigilantly censorious” impulse: “They are writing of the Negro multitude […] in such a style that people will stop and remark, Why, I thought I knew Negroes, but if I am to credit this story here I guess I don’t.” In a wonderful flourish, Walrond advocated “going into the lives of typical folks—people who don’t have to wait till the pig knuckly parson says good-bye and goes out the gate before they can be themselves” (“Negro Literati” 32–33). If he did not wait for the departure of the “pig knuckly parson” to read suggestive passages about purple chemises, Walrond did feel compelled to subject the tut-tutting of his detractors to satirical treatment. He was sensitive, took insults to heart, and could be aggressive in print.

The 135th Street library was a proving ground, and Walrond made an indelible impression. The discussions did not stop at the door nor was a clear line drawn between socializing and developing one’s craft. Regina Anderson, a librarian and writer, shared an apartment at 580 St. Nicholas Avenue with Louella Tucker and Ethel Ray Nance, hosting salons and extending hospitality to many aspiring artists who were moving to New York or passing through. Walrond became a fixture. “The 580 trio was excited by Walrond,” writes David Levering Lewis, by “his accented, rippling wit, his urbanity and fearless independence.”24 Among a group of regulars that included Cullen, Bennett, Hughes, and Harold Jackman, a Harlem schoolteacher, Walrond was a charismatic presence. Nance recalled, “You would think of him as being tall,” but “he may not have been six feet. [H]e was of slight build, had flashing eyes, his face was very alert and very alive.” She described his vitality and magnetism.

He was very pleasant, but as soon as he entered a room, you knew he was there. He moved very quickly, he couldn’t stay still and in one place, especially if he was excited, and he was excited most of the time. Either he had met someone or else he had a new idea about something and he would have to walk up and down when he described it or when he talked to you. He had quite a way of meeting strangers, anyone who ever met him remembered him.25

It was due as much to these personal qualities as to his talent that Walrond gained a wide acquaintance, in Harlem and downtown. He became a catalyst for the New Negro movement, “A person that held our little group together and built it,” said Nance, “because he had the faculty of bringing in interesting people and meeting interesting people. If Eric walked down the street, someone interesting was bound to show up.”26

Among the most interesting of Walrond’s acquaintances was Holstein, who was unwelcome at 580.27 The banker for Harlem’s illicit numbers racket, he “combined the prosaic traits of a financier with the dizzy imaginative flights of a fingerless Midas.”28 Holstein financed Opportunity contests and supported Walrond so generously that he dedicated Tropic Death to him.29 If Holstein was too disreputable for the 580 set, Walrond’s other close friend, Countée Cullen, was a pillar of respectability. Cullen was not wealthy, the adopted son of a Baptist minister in Harlem, but he was exceedingly proper. He was candid about his elitism: “I am not at all a democratic person,” he wrote Jackman in 1923, “I believe in an aristocracy of the soul.”30 Jackman was handsome, bright, and popular, and his relationship with Cullen was intimate, leading to jealousy among their peers, especially Walrond. Cullen expressed concern to Jackman: “So Walrond feels jealous of our friendship? Well, other people do too. I am wondering whether Walrond received the letter I sent him nearly two weeks ago. He has not answered. […] When you see him mention it to him, and if he did not receive the letter, secure me his address that I may write to him. I don’t want him to feel slighted.”31 His kind concern for Walrond’s feelings was matched by his admiration for his talent. “When the August [1923] Crisis comes out, be sure to get it,” he told Jackman, “The issue will be devoted to the younger Negro literati, and […] I wonder if Walrond will be represented. He ought to be.” In fact, Walrond was represented, and although his contribution took the modest form of an article on an Afro-Spanish painter, Cullen’s sense that his friend belonged in any showcase of “younger Negro literati” was now widely held.

The clearest illustration was the arrival in 1923 of the most prolific period in his career to date, with eight publications: a short story and two sketches, four articles, and a review essay. His sketches were the first works of fiction to appear in Opportunity. “On Being a Domestic” recounts the trials and tribulations of a hotel service worker at whom white patrons hurl epithets, glower, even expectorate “a cataract of saliva” (234). It was among Walrond’s efforts to highlight the plight of servitude and express the attending “passionate feeling of revolt.” Published in the next issue of Opportunity, “The Stone Rebounds” was equally fatalistic: “It is useless trying to run up against a stonewall—a Gibraltar of prejudice. Useless!” (277). Walrond’s bitterness during this period is even more pronounced in “Miss Kenny’s Marriage,” a satirical story without one sympathetic character. This may have recommended it to Mencken, the acerbic editor of The Smart Set. It was a fable eviscerating social pretensions in Brooklyn’s African American community, inviting readers to join him in a laugh at his characters’ expense. These are Miss Kenny, a beautician with a propensity for self-aggrandizing prevarications, and her suitor, the young lawyer Elias Ramsey. The story is a ribald portrait of 1920s black Brooklyn. But as the tale unfolds and it becomes clear that the quiet but unscrupulous Ramsey is fleecing Miss Kenny of all ten thousand of her hard-earned dollars, one wonders what exactly the author is after. Is it the pleasure of seeing the pretentious Miss Kenny brought low? Is it a cautionary tale about the perils of entering lightly into the pecuniary arrangement of marriage, a subject that was on the mind of its recently separated author? Neither interpretation rings quite true, for Ramsey is no more virtuous than Miss Kenny, whose fall is thus difficult to relish. Nor does the story offer an alternative to conventional marriage, making the cautionary tale incomplete. Instead, it might be understood as a trickster narrative.

From the outset, Miss Kenny is established as fatuous and haughty, an easy mark for the trickster. We are made to understand that she lies routinely and effectively. “Not that Miss Kenny was a four-flusher in the ordinary sense of the word. Heavens, no! She simply delighted in beating around the bush and misleading folks as to her personal affairs” (150).32 On “the matter of money” she was given to fabrication. “Yes, Miss Kenny had money. Of course she could never admit it. She always made it a point to impress strangers (and friends alike) with her utter destitution” (151). And though she was not “a member of the olive-skinned aristocracy of Brooklyn, there was evidence abundant to testify to the esteem in which she was held by, as she pertly expressed it, ‘gangs and gangs of folks’” (158). She is contemptuous of “niggers,” though of course she uses this term to refer strictly to a certain class, those whose coarseness reflects poorly on the race. “There ain’t none of the nigger in me, honey,” she tells a customer (153). When she hears that people are asking why she is still “doing heads” since she has married and can afford to retire, she declares, “That is just like us cullud folks. I tell you, girlie, I am not like a lot of these new niggers you see floating around here. A few hundred dollars don’t frighten me. Only we used-to-nothing cullud folks lose our heads and stick out our chests at sight of a few red pennies” (159). Thus, it is not surprising that the trickster who ruins her comes in the guise of a refined gentleman. “Miss Kenny’s Marriage” probably appealed to The Smart Set because of its jaundiced tone but also because it departed from the well-worn paths of propagandistic and sentimental fiction. Willingness to air the race’s dirty laundry was taken by many as the sign of mature confidence, a repudiation of the “inferiority complex,” and a commitment to authenticity over public relations. Miss Kenny, apparently a recent arrival from the South, calls her customers “honey,” “girlie, and “chile,” and Walrond orchestrates diction and syntax to suggest fidelity to “Negro” speech. But to read the story for its realism—its warts-and-all treatment of black New Yorkers—is to miss its affinity with other trickster tales, from Chesnutt’s “conjure stories,” to the tales of Br’er Goat and Anansi the Spider recited in the West Indian communities of Walrond’s youth.

Putting it this way reveals continuities that characterize Walrond’s early fiction, which otherwise seems to divide neatly between stories about New York and about the Caribbean. In subsequent months, five of his Caribbean stories appeared. Informed by his recent sea voyage, they included three in mainstream weeklies and two in Opportunity. All invoke obeah, voodoo, or another form of conjure, and three involve tricksters who steal the show.

CARIBBEAN STORIES

Composed in 1923, these five stories were a dress rehearsal for Tropic Death, anticipating that book’s tremendous vitality as well as its weaknesses. They are transnational and multilingual—representing the region’s startling diversity to an audience largely unacquainted—and generically hybrid, blending travel narrative conventions with pulp fiction and Afro-Caribbean folklore. Like Tropic Death, they drew on Walrond’s experiences in Panama and suggest the profound impact of the United States in the Caribbean, more often through ironic gestures than overt arguments. The concern for narrative detail that Tropic Death exhibits is evident in these stories, but above all they dramatize the tension between the natural and the supernatural, reason and unreason, that Tropic Death would treat as distinctively Caribbean. Walrond could not afford to write literary fiction and, unlike Tropic Death, these stories—two of which appeared in Opportunity, two in Argosy All-Story Weekly, and one in Success Magazine—were not intended to challenge readers but to entertain them and earn their author a paycheck. The circumstances of his departure from the UNIA are unclear, but he was no longer writing for Negro World and not yet on staff at Opportunity. The stories sought to appeal to U.S. readers despite esoteric cultural references and unflattering depictions of white Americans. For this reason, they exhibit a jarring double discourse: a discourse of tropicality, structured by oppositions between civilization and barbarism, culture and nature; and a discourse of coloniality, the insider’s perspective that renders real Caribbean lives, subverting the exoticizing gaze of the outsider.33 It was not until Tropic Death that Walrond coordinated these discourses with sufficient skill that they became mutually transformative rather than discordant.

These stories’ protagonists are all Afro-Caribbean. In “The Godless City,” Ezekiel Yates is a Jamaican who arrived in Panama in the 1880s and worked as captain’s assistant on an American gunboat. In “The Silver King,” Salambo is Puerto Rican, an aspiring poet whose fiancée lives in Guatemala, where his ship is headed. “The Voodoo’s Revenge” features Salambo’s anagram, Sambola, a St. Lucian, servant to the manager of the West Indian Telegraph Company, and another Afro-Caribbean, Nestor Villaine, editor of a Panamanian newspaper. In “The Stolen Necklace” Santiago is a Barbadian whose six years in Colón “duly Latinized” him and landed him a job at the Isthmian Canal Commission. Finally, the character most closely modeled on the author is Enrique, protagonist of the only first-person story, “A Cholo Romance.” A resident of Bottle Alley, Walrond’s own street, Enrique is a Colón businessman with political connections and a West Indian whose blackness makes him a despised chombo in the eyes of his mother-in-law to be.

These stories all undertake a generic masquerade. Walrond depicts the folkways and geography of Panama and the Caribbean, but his narrative voice and plot conventions come from hard-boiled pulp fiction. Men match wits and exploit one another’s vulnerability, which is almost invariably occasioned by too fervent an attachment to a woman. Salambo, Santiago, and Enrique are all blinded by their love for Latina damsels, while Nestor Villaine is blinded by his desire for revenge. In this vulnerable state, they are targets for the tricksters and agents of deception who populate the tales. Santiago tries to bamboozle a U.S. Marine eager to make some quick cash but finds in the end that he has gained a wife and lost a fortune. Sambola also winds up betrothed and missing a trunk of silver that he thought was his wedding gift. Enrique calls in a debt from a friend to help him outwit Br’er Goat, only to find himself engaged to Br’er Goat’s daughter at the story’s end. And Nestor Villaine, who enlists the services of an obeah expert to thwart his nemesis the governor, ends up a meal for the sharks in Limón Bay. In this genre, plot development could be finessed with melodrama and meaning could be retrofitted onto clumsily executed plots through ironic conclusions, preposterous epiphanies that resolve the narratives that precede them and excuse their deficiencies.

Walrond employed these dime story conventions in part because they were expected in magazines such as Argosy and Success but also because he grew up reading them. Enrique of “A Cholo Romance” is an avid reader of Dick Turpin, an English pulp series, and he speaks like one:

After getting as much fun as it is possible to get out of watching a wet canary dry itself in the sun, I stuck my head between the leaves of a Dick Turpin yarn. Black Bess had just jumped off one of London’s tallest skyscrapers, and Dick, eluding his captors, was Johnny-on-the-spot as the shining steed landed on its feet. With his usual dash he leaped into the saddle and in a jiffy was lost from view! (178)

Walrond illustrated his youthful enthusiasm for dime novels in “The Voodoo’s Revenge,” where he credits such reading with firing the imagination. Mr. Newbold, the story’s least sympathetic character, takes his “office boy,” Sambola, for a “faithful and obedient servant” because unlike his other employees Sambola “never smoked or whistled or stayed out late at nights or read ‘Old Sleuth,’ ‘Dick Turpin,’ or ‘Dead Wood Dick.’ He hadn’t any imagination. That, Mr. Newbold felt, was good for him” (212).

The minstrel figure was another feature of pulp magazines, where nonwhite characters rarely escaped the broad brushstrokes of caricature. “The Silver King” makes overt recourse to this convention. The title character, an African American southerner whose job is to care for the ship’s silverware, is ostentatiously proud of his work, which is, after all, quite mundane.

Chest thrown back, tall, black, majestic, the Silver King, a Mississippi roustabout, walked with the dignity befitting a man of his nautical station. More than any other member of the crew […] he was physically and metaphysically best suited for his treasure hoarding job. As guardian of the ship’s silver and basking in the sunlight of the grandiloquent title of “Silver King,” it devolved on him to hand out to the waiters and stewards at mealtime the sterling cups and dishes and knives and forks and sheeny platters. In this he ruled like a tyrant. (291)

When Silver King opens his mouth, out pour malapropisms, mispronunciations, and other deformations of standard English. “Say, where dat spoon come from at? […] Well, lissen, pardner, dis joint shets down at six—six sharp—and lissen, pardner, I gots orders from de boss not to recept nothin’ from nobody no time atter that. So gwan!” (291–92). His retorts are floridly metaphorical. “Say, lissen, tie dat bull outside. You can’t hand me none o’ dat gaff. Ma name ain’t Green. Wha’ do ya think I bin gwine ter sea all dese years fo’? I ain’t no monkey chaser” (294).

Insisting he is no “monkey chaser,” Silver King uses a pejorative term for West Indians. But in an ironic inversion, it is Silver King’s speech that Walrond marks, while Salambo, who is not only Caribbean but also a native Spanish speaker, somehow delivers lines in impeccable English. “I am going to get married,” he tells Silver King. “Zat so? Well, wouldn’t dat kill ya?” replies Silver King, “Marry! Wha’ fo’?” “You don’t understand, Silver King. Elisa is a lady—a nice Spanish lady—and I love her. She has consented to marry me” (294). It is an interesting choice for a West Indian writing in a mainstream publication. Walrond establishes Salambo as a “Negro” (one crewmember calls him the “laziest coon I evah seen in mah whole life”), but his unmarked speech distinguishes him from his African American shipmates. What did it mean for Walrond, a West Indian immigrant, to write vernacular for his African American character and standard English for his Caribbean character? As an author, this was a cross-cultural, intraracial masquerade. Caricaturing African American speech, it illustrates Walrond’s experimentation with polyphony and masking, a process Chude-Sokei has called “learning to both be and play an African American.”34 Employing the time-honored American trope of the “happy darky,” the story exhibits a supposed authenticity of character. But its artifice is revealed in the very different speech of Salambo, a Sambo on the lam.

But the story is a trickster tale, and just as Silver King gets the best of Salambo in the end, so Walrond engages in a form of narrative tricksterism, his “disgusting darky story” exhibiting popular stereotypes yet subverting them. It turns out that Silver King is only apparently ridiculous; he is sophisticated beyond his modest station. When Salambo reads samples of the verse he composed on the moonlit deck, Silver King calls it mere “mought-water” and lectures him about Paul Laurence Dunbar. In contrast to Salambo’s limpid doggerel, Silver King belts out Delta blues in a “golden basso profundissimo.” Just as Silver King generates certain expectations only to subvert them, Walrond deploys then deforms the minstrel mask, subverting the expectations generated by Silver King’s ostentation and palavering.

If there is more at work formally in “The Silver King” than appears at first glance, it makes no literary pretensions and is really just a lark. Although literariness was not necessarily prized in pulp fiction, these stories are significant for their polyphony and their colonial sensibility. These elements distinguished them from most everything being written at the time. The implicit question Walrond asked was: How could cross-cultural, transnational knowledge be represented in literature? The dominant models were Anglo-American travel and romance narratives. He knew their conventions well, but he was aware of their limitations and distortions. In 1924, he assessed the tradition against which he would define his own practice: “Usually a Melville or a Stevenson can get into a portrait of the tropics an idea of the beauty of nature—the emerald sea, the golden sands, the pearly lakes and teeming forests. It is when they come to the problem of delving into the complex nature of the natives that most of our writers […] slip and make asses of themselves” (“Our” 219). Nowhere was Walrond’s break from the Anglo-American tradition more pronounced than in his depiction of Panama. North American readers were familiar with the region because the canal was such a productive site of American national sentiment, generating a certain kind of knowledge. Articles, books, and photo essays issued forth, a mythology of U.S. technology, ingenuity, and determination. However, just as Caribbean labor was all but excised from this narrative, so too was the impact of the occupation and the complexity of the resulting society. Despite their eccentricities, Walrond’s pulp stories examined the region’s cultural hybridity, its legacy of creolization, and its challenge to Anglo-American powers of discernment.

There is not one Panama story, for example, in which Walrond fails to address the Canal Zone’s racial segregation, which effectively sorted residents by wealth and privilege. White Isthmian Canal Commission (ICC) employees lived in Cristóbal, across the bay from the Caribbean workers and families in Colón, cheek by jowl alongside Panamanians, Asians, and others drawn to the region. A frontier sensibility and an entrepreneurial culture suffused the area, compelling interaction across language, ethnicity, class, and nation. The failure of Anglo-Americans to conceive Caribbean complexities also registers at the level of plot and character. Whites do not come in for satirical or overtly critical treatment, but they embody a peculiar paradox: possessed of extraordinary power and privilege in the Canal Zone, they are blissfully ignorant of and vulnerable to the knowledge and modes of expression of the nonwhite residents. The nonwhite Panamanians in these stories share a counterknowledge set at a subversive angle to North American mythology. As in the trickster tradition, official power and privilege are always susceptible to reversal.

Walrond pursued an equivocal project in these Caribbean stories, invoking Conradian tropes of civilization fraying at the edges into barbarism, yet insisting on an intricacy and counterknowledge inherent in coloniality. Anxious not to “pollute” art with propaganda, he had been pursuing separate projects in his journalism and fiction. Clever and vibrant, the Caribbean stories were innovative without being poignant, saleable but flawed. His investigative reports on migrations demonstrated his grasp of their implications but did not stray from empiricism and reasoned argument. To reach the achievement Tropic Death represented, he needed to hone his craft but also to blur the line between art and politics. A fiction equal to the transformations he witnessed would not stop at dialect, folktale, and tropical sunsets; it would incorporate his recognition that the Afro-Caribbean diaspora was nothing less than a decisive convulsion of modernity. Had he followed established paths, he would have continued writing lively but disposable sketches and perhaps advanced as a journalist. That he did not is a testament to his self-willed transformation as a writer and to the influence of Opportunity’s quietly ambitious editor.

OPPORTUNITY KNOCKS

Opportunity was arguably the single most important periodical to the New Negro literary movement. Others had higher circulations and featured writers and artists prominently, but they were drawn into the arts in part by the initiative and success of Opportunity, founded in January 1923.35 As a forum for the finest talent of the era, Opportunity was exceptional; few New Negro writers published there first, but none escaped its notice. Hughes and Hurston credited editor Charles Johnson with launching their careers. He “did more to encourage and develop Negro writers during the 1920s than anyone else in America,” Hughes wrote.36 Hurston said she “came to New York through Opportunity, and through Opportunity to Barnard,” calling Johnson the “root” of the movement.37 When Walrond became business manager in 1925, he had been publishing there since its inception.

The defining document of the Harlem Renaissance is widely held to be The New Negro, conceived at the downtown Civic Club in March 1924, where a group known as the Writers Guild was introduced to New York’s publishing establishment. Locke and Du Bois are credited with orchestrating the Harlem Renaissance, but the impact of Charles Johnson, a sociologist trained at the University of Chicago and recruited to the New York headquarters of the Urban League, was equally decisive. For someone so prolific, “written evidence of his vast influence on the Harlem of the New Negro is curiously spotty,” notes David Levering Lewis. “It seems to have been his nature to work behind the scenes, recruiting and guiding others into the spotlight.”38 Johnson’s self-effacement belied his true impact. Attending to Walrond’s career not only reveals a hidden transcript of Johnson’s activity, it suggests that Walrond himself provided more impetus than is generally thought.

In summer 1923, Walrond and Countée Cullen were estranged and managing vexatious personal and professional problems. Both struggled in their intimate relationships—Walrond looking to exit a marriage, Cullen looking to get into one. Walrond’s relationship with Edith was further strained when they conceived a third child in August 1923. That fall, his family left for Kingston without him. Cullen was engaged in some soul-searching of his own, convincing himself that the right woman could cure him of homosexuality. He wrote frequently of this “problem” to Locke, whose homosexuality was an open secret. However, soon the reticent preacher’s son was cavorting with Yolande Du Bois, whom he recently met. He was smitten, as he told Locke: “I believe I am near the solution of my problem. But I shall proceed warily.”39 Cullen’s cryptic phrasing is illuminated by his other correspondence, which expressed alternately and with equal desperation his need to overcome his homosexuality and his need to find a discreet, compatible male partner. Locke disapproved of the relationship with Yolande as “a solution.” “I can forgive you for refusing my advice,” he fulminated, “but I cannot forgive you for transgressing a law of your own nature—because nature herself will not forgive you.”40

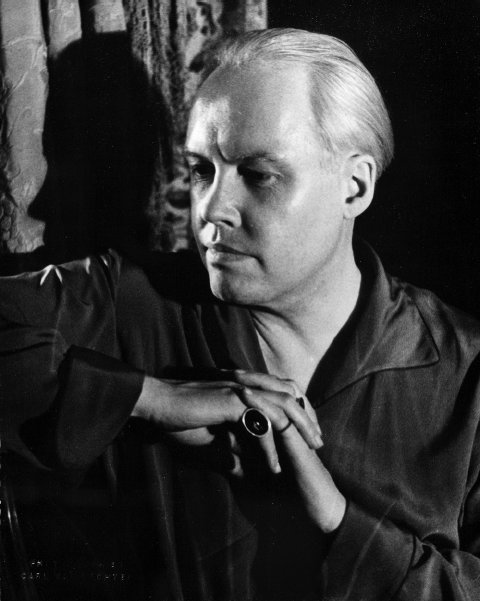

4.3 Photograph of Countée Cullen, 1932, photographer unknown.

Courtesy of the New York Daily News.

Just as Walrond and Cullen both struggled with their personal lives, they imposed similarly stringent demands upon their artistic development. Each sought to reconcile a desire to transcend sentiment and propaganda in art with a desire to address urgent issues of race. Walrond inveighed against efforts to disguise sociological narratives as good fiction, and Cullen, an admirer of Keats and Millay, took the occasion of receiving the Witter Bynner undergraduate poetry prize to lament the traces of race consciousness in his poetry.41 Walrond began talking seriously with friends in late 1923 about bold collective steps to publicize their work, and Cullen was among the first he approached. Walrond wrote breezily from Atlanta, where The International Interpreter sent him on assignment. Enjoying his most prolific period to date—eight publications in one four-month stretch—his Caribbean stories were placed, and Success declared him in a bit of puffery a “new, young master of vivid narrative” with “the making of one the greatest novelists and short story writers of our day” (32). Walrond was thrilled about his role in Harlem’s artistic ferment but self-conscious that his talent was surpassed by peers such as Cullen.

My dear Countée: Well, old fellow, it is Saturday night and I thought I’d drop you a line. I arrived here Monday, after a terrifying experience (which is not going to be without its literary effects, no matter how feeble) on the Jim Crow Car from Washington. I really cannot understand how folks travel that way year in and year out. I can’t.

I read Lucien White’s write up of you in the “Age.” It was fine. That is the sort of recognition that is going to help us put our ideas over. I think if everything goes well we ought to be thinking keenly on that score very soon. What with my success as a hack writer and your growing popularity as a poet of the first rank we ought to be able to do most anything, from seducing Sadie Peterson to conquering Joe Gould’s prejudices against the bath tub. […]

I ought to tell you something of the life and my work and experiences here. Atlanta, Countée, is alright for anybody who wants to be a Babbitt, but for a poet or one who is sensitive to the finer things in life it is a pig sty.

Of course I am on a Babbitt-wooing mission, and in that capacity I stand ready willing and able to the gums to resist the emoluments of any of you poets and liberals and neo-liberals and backwoods yankees and nigger upstarts and […] fundamentalists and apostles of culture and idealism and beauty and all such rot.42

Despite the wry self-deprecation, Walrond’s ambition is clear; he felt the time was right to “put our ideas over” and enlisted Cullen’s help in “thinking keenly on that score.” The “Babbitt-wooing mission” was a campaign to publicize the Commission on Interracial Cooperation, a federal initiative, but as his ironic closing suggests, he preferred poets, apostles of culture, and others “sensitive to the finer things in life” to the businessmen he was sent to meet.

Walrond’s eagerness to take bolder steps found a sympathetic ear with Charles Johnson. Trained by the eminent sociologist Robert Park, Johnson’s analysis of the 1919 race riots led to a directorship of the Urban League’s Division of Research and Investigations. His empiricism was tempered by a faith in the arts as transformative of public opinion and a conviction that “black artists should be free, not merely to express anything they feel, but to feel the pulsations and rhythms of their own life.” Some have cast Johnson as a cunning opportunist, exploiting the “Negro vogue,” but this neglects his commitment to publicizing and theorizing the arts.43 As George Hutchinson has shown, his intellectual orientation was shaped by pragmatist philosophy, in which cultural self-expression was as highly prized as dispassionate analysis (176).44 He saw the present group of writers as “the legitimate successors of the voices that first sang the Spirituals.” The audacity of his vision is difficult to grasp in retrospect, but for its time Johnson’s approach to the arts as at once beautiful and useful to the cause of interracial understanding was exceptional.

By February 1924, the group had hatched a plan and Johnson resolved to recruit Locke. He wrote about a “matter which is being planned by Walrond, Cullen, Gwendolyn Bennett, myself and some others, which hopes to interest and include you.”

I may have spoken to you about a little group which meets here, with some degree of regularity, to talk informally about “books and things.” Most of the persons interested you know: Walrond, Cullen, Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Bennett, Jessie Fauset, Eloise Bibb Thompson, Regina Anderson, Harold Jackman, and myself. There have been some very interesting sessions and at the last one it was proposed that something be done to mark the growing self-consciousness of this newer school of writers and as a desirable time the date of the appearance of Jessie Fauset’s book was selected, that is, around the twentieth of March. The idea has grown somewhat and it is the present purpose to include as many of the new school of writers as possible. […] But our plans for you were a bit more complicated. We want you to take a certain role in the movement. We are working up a dinner meeting, probably at the Civic Club, to which about fifty persons will be invited. […] You were thought of as a sort of Master of Ceremonies for the “movement.”45

4.4 Photograph of Charles S. Johnson, 1948, by Carl Van Vechten.

James Weldon Johnson Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. Courtesy of the Van Vechten Trust.

Like Walrond and Johnson, Locke saw this generation’s work as a threshold. “We have enough talent now to begin to have a movement—and express a school of thought,” he wrote Hughes.46

Fauset had gone to great lengths to solicit contributions to The Crisis and to cultivate an audience for creative writing, setting to work in 1922 on a novel of her own. At the same time, Toomer gathered his writings into a manuscript, and the resulting books, There Is Confusion and Cane, were published by Boni & Liveright within seven months of each other. Walter White signed with Knopf for Fire in the Flint, and work by African Americans appeared in “little magazines” and mainstream venues alike. But the cultural terrain truly shifted with a classical music performance, the American debut of Roland Hayes, an African American tenor who had electrified European audiences. First appearing with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, then at New York’s Town Hall, “Hayes promptly became a national symbol, if not a legend,” recalled Arna Bontemps, “the first of his color to invade the closed precincts of top-level concert music in this nation.” And “Charles Johnson did not fail to put it all in context.”47 It was a propitious time, Johnson realized, to stage a publicity stunt. Walrond and the others meeting at Regina Anderson’s apartment found an enthusiastic champion in the staid sociologist.

Johnson’s position and tact helped him pull off something unprecedented in African American letters. By enlisting the help of Locke and Fauset, yet keeping Fauset’s boss and the folks at The Messenger out of the planning, he and the Writers Guild recruited an extraordinary range of white publishers and editors for the Civic Club event, a dinner that featured presentations from Locke, Van Doren, and Liveright and readings by Cullen and Bennett, among others.48 Johnson benefited from Walrond’s assistance because he “made his own contacts” and “would go out and seek editors and publishers […] rather than rely on friends or agents or other people.”49 Their plan was not self-evidently promising, and some thought it inadvisable. Was it not the height of folly, while lynching and intimidation prevailed in the South and discrimination was rampant in public life in the North, to neglect questions of power and politics and expect literature to advance material progress? But Johnson was a shrewd promoter, articulating his convictions about the arts in advance of the event: “There has been manifest recently a most amazing change in the public mind on the question of the Negro,” he editorialized. “There is a healthy hunger for more information—a demand for a new interpretation of characters long and admittedly misunderstood.” Although “formal inter-racial bodies” deserved some credit for effecting this change, Johnson held “the new group of young Negro writers” primarily responsible.

[They] have dragged themselves out of the deadening slough of the race’s historical inferiority complex, and with an unconquerable audacity are beginning to make this group interesting. They are leaving to the old school its labored lamentations and protests, read only by those who agree with them, and are writing about life. And it may be said to the credit of literary America that where these bold strokes emancipate their message from the miasma of race they are being accepted as literature.50

His examples were Toomer, “author of the exotic ‘Cane,’” and Walrond, whose “quite unqualified appraisal” by Success he cited.

The guest list was long and luminous, including Eugene O’Neill, H. L. Mencken, Oswald Garrison Villard, Zona Gale, Ridgely Torrence, “and about twenty more of this type,” Johnson’s invitation said. “This type” included Arthur Spingarn of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) founder Roger Baldwin; art collector and philanthropist Albert Barnes; philosopher John Dewey; editors from The Nation, Harper’s, Scribner’s, and Survey; columnists Heywood Broun and Konrad Bercovici; and novelists Rebecca West, Gertrude Sanborn, and T. S. Stribling. Among the celebrated African Americans were Robeson, James Weldon Johnson, Walter White, J. A. Rogers, and Montgomery Gregory, along with the Writers Guild members: Walrond, Cullen, Anderson, Hughes, Fauset, Bennett, Jackman, and Eloise Bibb Thompson. As he opened the responses, Johnson realized the scale of the thing. “No accidents can afford to happen now,” he told Locke, “The idea has gone ‘big.’”51

By any measure, the event was a huge success. That Friday evening in March, the Greenwich Village venue was abuzz with more than one hundred revelers. Opportunity claimed, “There was no formal, prearranged program,” just “a surprising spontaneity of expression both from the members of the writers’ group and the distinguished visitors.”52 But in fact, Charles Johnson, ever the impresario, carefully orchestrated the proceedings, directing Locke to meet him that morning to review plans. Several speakers prepared remarks, Cullen and Bennett were asked to read a poem each, and Van Doren and Barnes were asked to deliver keynote addresses. Thus, if anyone exhibited “spontaneity of expression” it was probably only Liveright, who was notorious for relying principally on liquid courage. No record survives of Walrond’s response, but one can imagine the satisfaction he felt. “Our little group,” as Nance called it, had engineered a stunning publicity coup. After Charles Johnson welcomed the guests, offering “a brief interpretation of the object of the Writers Guild,” Locke, Du Bois, and James Weldon Johnson delivered speeches, striking a common theme: the younger writers’ refusal to indulge in apologies or “inferiority complexes.” This was also, Liveright said, the chief virtue of Cane, whose merits he affirmed despite poor sales. For Walrond, it must have been gratifying to hear Liveright challenge the audience to “test the waters of black talent with a few publishing contracts,” and exhilarating to hear poems from his friends Cullen and Bennett, who concluded the evening with “To Usward,” likening the new generation to ginger jars gathering dust on a shelf, “sealed/ By nature’s heritage.” They were ready, Bennett declared, “to break the seal of years/ With pungent thrusts of song.”53

“A big plug was bitten off,” Johnson declared, “Now it’s a question of living up to the reputation.”54 Walrond’s behind-the-scenes effort ensured that the event yielded results. “When the dinner ended, Paul Kellogg, editor of the Survey Graphic, stayed on to talk to Countée Cullen, Eric Walrond, Jessie Fauset, and the others and then approached Charles Johnson with an unprecedented offer. He wanted to ‘devote an entire issue to the similar subjects as treated by the representatives of the group.’”55 This would be the Survey issue “Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro,” which was guest-edited by Locke and sold 42,000 copies, double the usual. In turn, the Survey issue became The New Negro, published in 1925. As important as Kellogg’s opening gambit, Du Bois announced a Crisis literary contest, as did Johnson later that year for Opportunity, and he and Liveright mobilized their publicity apparatus. Boni & Liveright advertised in the New York Times Book Review, announcing Fauset’s novel and trumpeting the event at which “the intellectual leaders of the metropolis celebrated the birth of a new sort of book about colored people.”56 Walrond was tasked with writing up the event for the New York World and sought Locke’s assistance gathering transcripts of the speakers’ remarks.57 News of the event spread, and Johnson reported that “a stream of manuscripts has started into my office.” It is no exaggeration to say that after March 1924, African American literature would never be the same.

The most tangible benefit for Walrond was the appearance in The New Negro of his story “The Palm Porch,” a lurid tale set in a Panama brothel. The story’s inclusion returns us to a recurring tension in Walrond’s career, for although he enjoyed the fruits of his labor with the Writer’s Guild, it came at a cost. The movement defined itself as an American phenomenon despite the contrapuntal accents of Caribbean immigrants. One in five black Harlemites was foreign-born by the late 1920s, but the movement bearing its name was framed in national terms, with the New Negro representing at once the inheritance and the proleptic overcoming of a spiritual legacy begun with the sorrow songs, sermons, and blues rhythms of the southern black belt. However, recent scholars remind us “just how seminal was the West Indian presence in the Harlem of the 1920s.”58

To some extent Locke, Du Bois, and Johnson were responsible for the nationalist contours of the movement. Their interests, although not unified, determined much of what was published and how it circulated. Du Bois and Locke were interested in the broader diaspora, but Johnson cut his professional teeth on the social problems of the Great Migration, and the consensus among interested whites was that “Negro” voices were a vital contribution to the chorus of American literature. To the extent that African American writers succeeded at chipping away at publishers’ prejudices, they did so because of the era’s push toward pluralism, a belief that American literature could only become American by emphasizing what made the United States distinctive, drawing on multiple ethnic traditions. Versions of this claim appeared regularly in the progressive journals. Van Doren’s remarks at the Civic Club expressed his “genuine faith in the future of imaginative writing among Negroes in the United States,” a “feeling” that they were “in a remarkably strategic position with reference to the new literary age.” His endorsement was representative of the effort to define New Negro literature as a tributary to the widening stream of American modernism. “What American literature decidedly needs at the moment is color, music, gusto, the free expression of gay or desperate moods. If the Negroes are not in a position to contribute these items, I do not know what Americans are.” He invoked novelty of expression and contrasted the “fresh and fierce sense of reality” issuing from African American pens with the “bland optimism of the majority.” Finally, he delineated the territory on which African American writers would base their “vision of human life”: “this continent.” When we understand the Harlem Renaissance as a pivotal era for African American literature we should also understand how American its framing was.59

How, then, did foreignness figure? One might note the prominence accorded Schomburg, McKay, Walrond, W. A. Domingo, and J. A. Rogers in The New Negro and conclude that this was a big tent, including non-Americans (at least males) and fostering intraracial understanding. However, differences of ethnicity, language, and nation were often elided in discussions of the movement, as bichromatic U.S. race relations assumed priority. On or about March 1924, as Walrond heard Carl Van Doren incorporate him into the grand unfolding of a distinctive American tradition, there were at least two reasons he and other West Indians were making tacit peace with their internal marginalization: the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act and the campaign against Garvey. As Locke departed Washington to join Johnson in planning the Civic Club event, Congress was crafting the most restrictive immigration legislation of the century, the Johnson-Reed Act. The immediate effect was to cut the number of immigrants arriving each year almost in half, with the heaviest contraction upon southern and eastern Europe. Immigration from the Caribbean was sharply curtailed, and nativism infused urban communities where Afro-Caribbeans lived in large numbers. Garvey was a lightning rod, his ethnicity and alien status regularly impugned. The “foreigner” angle gained virulence, and the terms “West Indian” and “ignorant” were frequently joined in close syntactic proximity. The Messenger conceded the existence of many “splendid,” “intelligent” Caribbean people but urged ministers, editors, and lecturers to “gird up their courage … and drive the menace of Garveyism out of this country.”60 This was opportunism, but it would not have been possible absent the nativism that delivered the Johnson-Reed Act.

Walrond was not immune to these pressures, and he sought to rescue West Indians from the nativist assault. Paradoxically, he did so through classic American values such as industry and thrift and through a ritualistic disavowal of Garvey. At the height of the “Garvey Must Go” campaign in 1923, he published two articles attacking the presumption “that Garvey, crude, blatant, egocentric, a mental Lilliputian, is the typical West Indian intellectual,” claiming instead that “Garvey by virtue of his upbringing, training, and early environment, is not representative of the best the West Indian Negroes have to offer.” Walrond called West Indians “the Hebrews of the black race,” a model minority for whom “America is the fulfillment of a golden dream” (“Hebrews” 468). To understand the West Indians’ promise, he pointed to other parts of the Americas, where they had been welcomed from Cuba to Panama to the banana fields of Guatemala and Honduras (“West Indian Labor” 240).

At this point, Walrond added a breathtaking bit of sophistry. “Endowed with the spirit of conquest of the Puritan settlers of the isles of the Caribbean, he goes to the ends of the earth, building, erecting, assimilating.” U.S. readers were to understand, in other words, that despite being black and foreign, perhaps West Indian Negroes most resembled Anglo-Americans, sharing a common Puritanism, an ethic of industry and “spirit of conquest” that took them around the world. If this were not enough to establish the affinity, Walrond distinguished West Indians from other Caribbean peoples on the basis of their Englishness. The “Negroes from Guadeloupe and Martinique” the French hired in Panama, “were not of the sturdy pioneering stock who were willing to weather the storms of malaria and disease and dig the ditch. […] The West Indians stuck to their guns, steeled their jaws, and fought the good fight” (241). It is a measure of the xenophobia of the times that Walrond, who was well aware of the imperialist dimensions of the U.S. role in Panama and its exploitation of black labor, would resort to this effort to establish the West Indian’s “sturdy pioneering stock.”