fter Tropic Death, things went so well that one wonders why Walrond left the United States. Why desert the country whose acceptance he sought? Why abandon Harlem as it emerged into prominence? Surveying 1926, Charles Johnson observed that “more books on the Negro have appeared than any other year has yielded, Broadway has welcomed three Negro plays, and with Eric Walrond, another Negro writer has moved definitely into the ranks of American artists with his fiercely realistic Caribbean tales.” His name appeared alongside Toomer, Hughes, and Cullen as writers of lasting import. “Eric Walrond automatically finds himself in this class,” said the Chicago Defender, “His stories will live as long as stories live.” There was no “discernible reason,” Robert Herrick felt, “why the creator of Tropic Death should not go much farther in this field, which he has quite to himself.”1

fter Tropic Death, things went so well that one wonders why Walrond left the United States. Why desert the country whose acceptance he sought? Why abandon Harlem as it emerged into prominence? Surveying 1926, Charles Johnson observed that “more books on the Negro have appeared than any other year has yielded, Broadway has welcomed three Negro plays, and with Eric Walrond, another Negro writer has moved definitely into the ranks of American artists with his fiercely realistic Caribbean tales.” His name appeared alongside Toomer, Hughes, and Cullen as writers of lasting import. “Eric Walrond automatically finds himself in this class,” said the Chicago Defender, “His stories will live as long as stories live.” There was no “discernible reason,” Robert Herrick felt, “why the creator of Tropic Death should not go much farther in this field, which he has quite to himself.”1It had been an exhilarating year at Opportunity, which now rivaled The Crisis in featuring creative work. Johnson redoubled his efforts, developing networks among African American writers and white publishers and editors. The first Opportunity literary contest drew 732 submissions from around the country and enlisted eminent editors and writers as judges. The awards exemplified Johnson’s care in cultivating a journal that was, after all, still in its infancy. More than 300 guests attended the inaugural Opportunity awards reception in 1925, and the crowds swelled over the next two years, filling the elegant Fifth Avenue Restaurant.2 Johnson combined passion with pragmatism. His expertise lay in the systematic synthesis of hard data, which he saw as the basis of any firm and lasting public policy. But he recognized the vitality of the emerging artistic community, and Opportunity’s circulation nearly doubled between 1925 and 1927, concurrent with its embrace of the arts.3 Walrond’s influence was vital. Opportunity had never had a steady business manager, and this one knew everyone. Having pitched to editors on both sides of the color line, he had extensive contacts and a measure of celebrity, moving among groups that did not always mix well. His heart and home were in Harlem, his office on 23rd Street, and his publisher in midtown. At the time of Tropic Death’s publication, Walrond’s work appeared in six periodicals, none of which regularly featured “Negroes.” He straddled the color line, interpreting developments in African American culture for white readers and providing a “Negro” perspective on white depictions of his race.

But what exactly was “his race”? Assuming the role of “Negro” spokesperson was an act of strategic identification. White editors may not have cared that he was from the Caribbean; they wanted someone with a command of African American cultural history and the experiential knowledge a black person inevitably acquired in the United States. However, among black New Yorkers, Walrond performed a different mediating role, bridging native- and foreign-born communities. He felt West Indian intellectuals could alleviate intraracial tensions and improve the ignorance among West Indians and African Americans of one another’s history. Garvey’s spectacular plight amplified the perception that West Indians were untrustworthy, perhaps un-American, an impression that their relatively low rate of naturalization did nothing to remove. The epithet “monkey chaser” was used, whether in jest or contempt, to disparage the uneducated, while the educated were accused of “putting on airs.” Hostility toward West Indians was compounded by academic studies such as The Fall of the Planter Class in the British Caribbean, which said of the West Indian “Negro,” “He stole, he lied, he was simple, suspicious, inefficient, irresponsible, lazy, superstitious, and loose in his sexual relations.”4 That the American Historical Association awarded this study its 1926 dissertation prize, the year Tropic Death was published, indicates how much work was to be done.

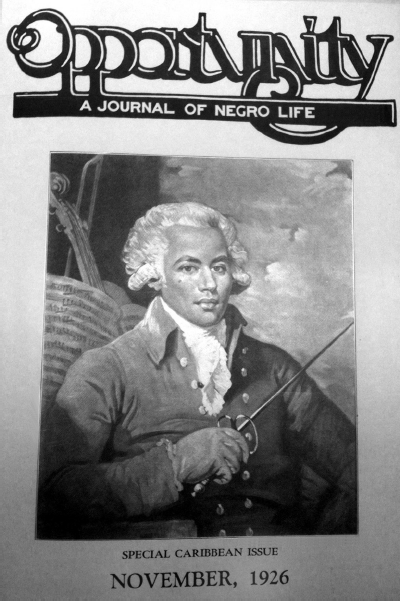

A CARIBBEAN OPPORTUNITY

After submitting Tropic Death, Walrond spent the fall developing a special issue of Opportunity devoted to the Caribbean. This issue was unusual because the Urban League rarely pursued projects beyond U.S. borders; the organization’s stated aim was to disseminate information about African American migrants relocating from the rural South. So extensive was this undertaking that Johnson, as director of the Department of Research and Investigations, seldom diverted his attention from migration. He was aware of immigration’s scale, Harlem’s foreign-born black population having increased tenfold in the first two decades of the century. But it did not register as distinctive in his work. In fact, when Johnson undertook a comparative migrations study in 1927, he examined the northward migration of African Americans in relation to European and Mexican immigration, omitting the Caribbean.5 Opportunity took no fervent interest in the Caribbean or Africa, nor did it devote much space to intraracial dynamics.6 Based on the progressive premise that “friendships usually follow the knowing of one’s neighbors,” the special Caribbean issue “aimed at an essential friendship,” Johnson wrote, granting the West Indian a forum at a time when “the American Negro is constantly present in his newspapers and magazines.” Walrond was indispensible for this project: “A native of British Guiana, who happens also to be the business manager of this journal,” he selected the “special articles which appear in these pages.” “We are indebted to his thorough acquaintance with the spokesmen of the Caribbean in this country.”7

These included Arthur Schomburg, who contributed “West Indian Composers and Musicians”; Claude McKay, three of whose poems appeared; W. A. Domingo, who offered a history of the region; and Casper Holstein, whose history of the Virgin Islands dovetailed with another contribution, “Caribbean Fact and Fancy,” by Virgin Islands chief justice, Lucius Malmin. When Schomburg declined to write an article about prominent West Indians, Walrond solicited one from the editor of New York’s West Indian Statesman.8 Rounding out the issue were Waldo Frank’s review of Tropic Death, an essay on Garvey by E. Franklin Frazier, and a “symposium” on West Indian-American relations between the Reverend Ethelred Brown of the Harlem Community Church and Eugene Kinckle Jones, the Urban League’s executive secretary. The column “Our Bookshelf” was also Caribbeanized, addressing books about Surinam, Brazil, and Haiti.

6.1 Cover of special Caribbean issue of Opportunity, 1926.

Courtesy of the National Urban League, Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life.

An extraordinary document of the diaspora, the Caribbean issue is shot through with ambivalence about the United States, a reflection of its guest editor’s own feelings. On one hand, it advanced the journal’s pluralist premise that, equipped with better knowledge of one another, ethnic groups could coexist amicably and share prosperity in the United States. “A bond is being forged between [West Indian] and American Negroes,” Domingo wrote, “Gradually they are realizing that their problems are in the main similar, and that their ultimate successful solution will depend on the intelligent cooperation of the two branches of Anglo-Saxonized Negroes.” As “Anglo-Saxonized Negroes,” West Indians and African Americans could surmount their differences, he suggested. The poems in the Caribbean issue, including Claude McKay’s, offered universalizing gestures rather than matters particular to the Caribbean diaspora. On the other hand, the essays by Malmin, Holstein, and Domingo challenged U.S. foreign policy and inveighed against American racism. Malmin reflected on the crossroads in U.S. foreign policy, given the “clamor in the Philippines, certain dissatisfaction in Porto Rico, outspoken woe in Samoa and Guam, desperation in the Virgin Islands.”9 Holstein called the purchase of the Virgin Islands a pretext for subjugation, and joined Malmin in warning of imperial designs. Alarmed at the prospect of U.S. occupation of the Caribbean, he observed that the Navy ruled the Virgin Islands “with the transparent subterfuge that it is governed directly by the President of the United States,” a ruse that “the inhabitants continue to protest.”10 Trepidation consumed all “informed and influential West Indians,” said Domingo, at the prospect of exchanging British for American rule. The virulence of American racism was a factor: “They fear that under the hegemony of the United States they would be made to experience the social degradation to which Americans of color are subject.”11

Despite the issue’s emphasis on the “shared Negro blood” of West Indians and African Americans, it could not evade the discrepant circumstances in which they established self-understandings of race. “Unlike in the United States, the full-blooded Negro and his brother of mixed blood are not classified as one” in the Caribbean, Domingo noted, “The latter occupies a position midway between the two pure races and is regarded […] as a link between white and black.” Contributors acknowledged that tensions strained relations between West Indians and African Americans, but the Caribbean issue maintained that conflicts arose from misapprehension. “The American Negro failed to discriminate between the different classes of West Indians, and thus mistakenly judged the best by the worst,” wrote Rev. Ethelred Brown.

This mistaken judgment engendered a feeling of contemptuous superiority. Later when the more intellectual and more cultured West Indian compelled recognition, contempt gave way to jealousy. The West Indian on this part, especially the intellectual and cultured, also erred in this failure to discriminate, and was on the whole much too self-assertive and in great measure by his words and conduct intensified the prevailing antagonism.12

Thus did Rev. Brown identify the “necessary misrecognitions” inherent in efforts to forge racial solidarity across national borders.13 The Caribbean issue of Opportunity did not treat failures of transnational racial identification like the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) did, as a conspiracy to keep “Negroes” disorganized. But it partook of a similar utopian desire for a unified community, casting the impediments to harmony as individual deficiencies of apperception rather than as discrepancies inherent in the translation of black experience. Intraracial differences were important to acknowledge but only as a stage in their extinction.

The Caribbean issue of Opportunity was Walrond’s effort to heal a rift that threatened to divide black New Yorkers. Having lived in two British colonies and a Latin American country under U.S. occupation, he was alert to the paradoxes of black transnational cultures, which, as Brent Edwards notes, “allow new and unforeseen alliances and interventions on a global stage” but also yield “unavoidable misapprehensions and misreadings, persistent blindnesses and solipsisms, self-defeating and abortive collaborations, [and] a failure to translate even a basic grammar of blackness.”14 Having enlisted leading voices, Walrond brought Opportunity into an important new conversation. The Caribbean issue fulfilled a pledge Walrond made in his earliest journalism: to demonstrate that the distinctiveness of Harlem lay not in its concentrated blackness but in the extraordinary diversity that blackness subsumed.

The Caribbean Opportunity included an announcement that Countée Cullen had been hired as assistant editor. Having just completed a well-received first book and a master’s degree at Harvard, Cullen’s arrival was called “a step virtually decreed by the demands of that awakening generation to which this magazine […] has consistently addressed itself.”15 He would contribute poems, editorial assistance, and a monthly column, showcasing his wit and analysis of race and culture. All had not been well, however, between Cullen and Walrond, for whom his friend’s success was the source of mixed pride and envy. When he first saw Color in the fall of 1925, he fired off a congratulatory telegram, calling the book “gorgeous.”16 Within a week he wrote again, contrite, for he had overlooked Cullen’s dedication of a poem to him. “I am sure it is well-nigh impossible for me to restore myself to your gracious graces. I am such a confirmed reprobate. I saw a copy of ‘Color’ and upon turning its pages I was entirely unprepared for the shock which I experienced upon seeing the dedication to ‘Incident.’ Now, is not that nice of you?”17 Walrond lavished praise on the book.

Your words are fraught with a high meaning; there is beauty and magnificence in the sentiments motivating them. You execute in your finished way the ideal which I have secretly held about Negro writing; utilizing material in its very essence virginal, the black poet or prose artist should fuse it into the drama via the avenue of the classical tradition. […] I look to [you] for strength, power, endurance, beauty, distilled vision. […] Endless emotions are orderly swept into the mosaic of your creations with an economy and compression.

He alerted Cullen, whom he affectionately called “kid,” to his own recent publications and closed by asking, “How do you like Harvard?” He added plaintively, “Write me, Countee.” But Cullen did not write, and Walrond despaired of their friendship. “With a telegram and a letter left unanswered I suppose we are quits,” his next letter began, “But I do want to hear from you.”18

Walrond did not realize Cullen was navigating personal travails of his own, circumstances he told Locke that same day. His companion, Llewellyn Ransom, was struggling with family obligations involving his marriage and now, with the holidays approaching, his vexations distressed Cullen.19 Walrond’s reconciliation with Cullen did not come easily. In response to his despairing letter, Cullen must have dashed off a quick message intended to mend things because Walrond’s reply began accusingly, “Your horribly inadequate note came today.” He added, “I am expecting you to be more generous with me when you come to town Thanksgiving.”20 Cullen restored himself to Walrond’s favor, and within weeks they were again corresponding in breezy tones.

For Walrond, Cullen’s Color was the realization of the terrible aesthetic potentiality of the Middle Passage and the creation of the New World Negro. “If, as some of us would have it, the presence of African slaves at Jamestown was ironically a fertilizing gesture of the Deity, Countee Cullen is the fulfillment of one of the pregnant promises of the New World” (“Poet” 179). Reviewing it for The New Republic, he refused to cast Cullen’s accomplishment in narrowly national terms. “In this first book of verse by a Negro boy but twenty-two years old there is proof of many synthesized cultures. Spreading over a wide area are the roots of the poet’s vision, incisive and unsentimental, fraught with objectives slightly imperceptible to him” (“Poet” 179). He felt the poems expressed “the Negro spirit”—“certainly the urge in that direction beckons strongest.” Wary of puffery and public relations, he nevertheless hazarded superlatives: “Ordained is a pretty bloated word, but if there ever was a poet ordained by the stars to sing of the joys and sorrows attendant upon the experience of thwarted black folk placed in wretched juxtaposition to our Western civilization, that poet is Countee Cullen” (“Poet” 179).

As his friendship with Cullen revived, Walrond began losing patience with Claude McKay, who asked him to shepherd his work around New York while he wrote in self-imposed exile in Europe. Walrond was not alone in receiving McKay’s entreaties; his correspondence with Louise Bryant and Nancy Cunard also conveyed exasperation with New York’s capricious publishers and lamented his abject poverty. He was always down to his last sou, in ill health or ill temper, and in desperate need of a check, preferably made out in francs. His desperation became acute during his attempt to shop his novel, Color Scheme. By all accounts a flawed book, Color Scheme was never published and McKay discarded the manuscript. But he initially felt Walrond could help him place it. He showed one of McKay’s letters to Lewis Baer in late 1925, who in turn contacted Locke, telling him McKay was “in Switzerland in dire distress. Eric wondered whether we could send him an advance on his share in ‘the [New] Negro.’ Even the smallest amount apparently would help him out.”21 Even as Walrond advocated, McKay found his efforts sluggish and asked Schomburg to prod him. Christmas Eve 1925 found Walrond defending himself to Schomburg: “I am sorry I had to give you cause to write me about McKay, but perhaps it is just as well as it forces me to do something which the rush of the holiday season had deprived me of the opportunity of doing.” Explaining his efforts on McKay’s behalf, he told of having read the novel and recommended it to two publishers despite his reservations and of attempting to obtain royalties from Harcourt Brace for poems they had anthologized. All the while McKay was writing “distressing letters” saying “he was terribly up against it” and enclosing poems for Walrond to “sell” if he would “consent to act as his agent.” “I trust, by this letter, you will see that I haven’t been asleep at the switch,” he assured Schomburg.22

McKay contacted Walrond again a year later, asking his assistance with submissions to Opportunity. Walrond told him it was “foolhardy to try to sell MSS from such a distance without an agent acting in your behalf.”

Everybody here is so selfishly busy marketing or performing for the market wares of his own that it is a waste of time to try to butt in anywhere. If I were you I wouldn’t bite my tongue when I write Johnson: tell him you are up against it and ask him what about the money he promised you for the stuff he has used. Bombard him to death; he’s sure to quiver under continuous fire. I’d suggest that you write A & C Boni again […] Du Bois is also offering upwards of $2,000 for literary prizes of all sorts and seems to be making an unexpectedly vigorous effort to get stuff by the younger men. I’d suggest that you re-establish relations with him.

McKay had asked Walrond about the status of The New Masses, which Walrond said was “going slowly to hell and is read by practically no one of consequence.” There was also “a chap here who is constantly talking to me about you,” an editor at the North American Newspaper Alliance, and he encouraged McKay to “drop him a line and tell him what you are trying to do.” In short, he was constructive and solicitous: “Can’t you try and get back to America? The world seems to have gone around a hundred times since you have been away.”23

McKay continued to rely on Walrond. It could take two weeks for letters between New York and Marseilles to arrive, and when they crossed paths consternation ensued. When Johnson rejected some work of McKay’s, McKay pressed Walrond to exasperation. “I am taking this means of passing on to you the following from a letter which I have just received from Mr. Johnson.” Walrond replied: “I am very sorry that Mr. Claude McKay has become exercised over the manuscripts which we had here in the office. However, I had written him saying that these stories about which he was very much concerned are to be returned, in fact, all of his manuscripts.” “This was from a letter dated June 27, 1927,” Walrond added peevishly, “I hope that this fully absolves me from the responsibility of having to jog Mr. Johnson’s memory about your MSS again.”24

McKay denounced Walrond years later to Nancy Cunard. Cunard was gathering contributions for her Negro anthology, and their correspondence ranged across a number of subjects and acquaintances.

I dislike Eric Walrond. And he does me too. Think he is very pretentious light-weight. Knew him when I was on the Liberator with Max Eastman and he on the Negro World with Garvey, 1922. Garvey had given me hell and more in his paper (he always had a grudge about me for showing up the preposterous side of his movement in the Liberator) because the police had broken up a Liberator affair and beaten some guests on account of my dancing with a white woman—Crystal Eastman—and the NY papers had made quite a scandal of it. Eric came to see me and gave me some inside dope on Garvey’s character for me to make a comeback attack—the crassest moral stuff and besides he was working for the man. Next time I heard from him was 1925 in France he wrote asking me to send stories for a competition in the Negro magazine “Opportunity” for which he was assistant editor & offered to place some stuff for me. I was glad to do it for I was quite broke. The stories and poems I sent in did not take the prize, but because I was known a little the magazine proceeded to print them without paying me. And so I put my agent on them to collect.25

There may be something to McKay’s account of the Garvey episode, but the Opportunity allegation does not comport with the evidence. Further, he wrote, “Walrond (in a widely reprinted article) said I had been invited to Russia by the Soviet Government and the impression was that I had become a Bolshevik agent. A lie.” In fact, the article, a 1929 review of McKay’s novel Banjo, was laudatory. Many reviewers skewered the book, not only for its licentiousness but also on technical grounds. Walrond’s review, published in London’s Clarion and Jamaica’s Gleaner, expressed a high tolerance for Banjo’s formlessness, calling it “terribly illuminating” (“Negro Renaissance” 15). But he criticized McKay’s dialogue, which undoubtedly provoked McKay’s ire. “I have gone carefully through his stories,” McKay said of Walrond, “and stripped of their futuristic verbiage they reveal nothing but the average white man’s point of view towards Negroes.”26 The fallout between the two was protracted but final. Despite their professional ties and shared Caribbean background, Walrond and McKay were temperamentally unsuited for friendship. Island chauvinism may have been a factor—Jamaicans and Barbadians sometimes harbored mutual suspicions—but McKay’s absence from Harlem during the period of the New Negro movement’s literary efflorescence strained his relationship with Walrond, as with others.

A ROMANCE

Three revelers dropped by Alain Locke’s New York apartment one evening in 1927, two contributors to The New Negro and a young woman, a recent University of Minnesota graduate, whom Du Bois had just hired at The Crisis. Having missed Locke, they left a hastily scribbled note. “Eric Walrond, a beautiful lady, and I (no—Eric wasn’t the “beautiful lady”!) found you out as usual. He is leaving tonight, despite the beautiful lady. I’m not. (Keep your mind in the right place, now!) Sorry we missed you. Marvel Jackson, Eric D. Walrond, R[udolph] F[isher].”27 Marvel Jackson was often in Walrond’s company in these years, and her absence from his extant papers is belied by the intensity of their attachment. They met while she was engaged to Roy Wilkins, who became executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), but Wilkins worked at The Kansas City Call and Jackson’s move to New York opened her eyes to other possibilities. “I came to New York right at the tail end of the Negro Renaissance and I met such wonderful, much more exciting young men, I thought, than Roy,” she recalled. “There was one that liked me very much; his name was Eric Walrond.” “I really thought I was going to marry him. I was really in love with him, the first time I had cared deeply about someone of the opposite sex.”28 Jackson’s reflections, recorded after an illustrious career in journalism and civil rights advocacy, offer a rare glimpse into Walrond’s private life. They also underscore his abiding interest in West Indian experience in the United States.

Walrond met Jackson during a brief visit she made from Minneapolis in 1926. “If I examined it, I wouldn’t be surprised if he weren’t one of the reasons I really wanted to come to New York.” Their relationship seems to have been the most durable of his attachments after his family’s departure in 1923. Jackson later married a schoolteacher, Cecil Cooke, and wrote for The Amsterdam News, The Compass, and The People’s Voice. She became a stalwart activist, organizing the Newspaper Guild, and a lifelong member of the Communist Party, refusing to name names during the McCarthy era and later serving as treasurer of the Angela Davis Defense Fund. Her story is fascinating in its own right, and it began when she moved to work at The Crisis, “a very thrilling experience for a little gal from Minnesota.”29

Jackson was attracted to Walrond in part because of his captivating social milieu. Through him she met artists and writers with whom she formed lasting friendships: Hughes, Cullen, Robeson, Thurman, Bontemps, and Aaron and Alta Douglas. She felt “lucky” to be there, dining at the invitation-only Civic Club with Jean Toomer, entering Lenox Avenue nightspots in “a mixed group, half white, half black,” and feeling “very safe” in doing so, accompanying Walrond to Robeson’s sendoff when the great baritone embarked to perform in London.30 “It was a close-knit group. They were talking about getting Guggenheim Fellowships. It was really an inspiring group of young people to be involved with. […] Coming from where I did in Minnesota, to this very vibrant and alive group of young people was wonderful.” She moved into an apartment at 409 Edgecombe Avenue in Sugar Hill. “I can imagine almost any young person just finishing college and getting into this sort of environment, being excited about it.” None of it would have been possible without Walrond: “All my social life was built around him.”31

Second, Walrond took Jackson seriously as an intellectual. Although most of her work at The Crisis was clerical, she wrote the column “The Browsing Reader” and was writing a novel about mixed-race children. She and Walrond had a regular routine. “We spent every evening after work at the Forty-second Street Library, where I wrote and he wrote. […] We would write until the library closed, and he would read what I had written. […] We’d go across to the Automat and he would go over the stuff I wrote, and he expressed himself that he thought I had a lot of ability. […] I thought I was going to write the great American novel.” Jackson never completed her manuscript, but she kept writing and joined workshops, including one in the 1930s that included a young Chicago transplant, Richard Wright. “[H]e used to come by every Saturday night to get some of my mother’s hot rolls. I think I read that first chapter of Native Son a million times. Every time he changed a comma in it, it seemed to me he had me reading the thing.” But “it wasn’t just for the writing” that Jackson valued Walrond, and “It wasn’t just because of the exciting people he introduced me to.” “It was just that I liked Eric […] he was quite a nice companion.” “I was really in love with him,” she said, “He was the first man that I had ever had any feeling for.”32

For his part, Walrond would have been impressed by and drawn to Jackson for a number of reasons, not least of which was her beauty. Three years his junior, she had fair skin and flaxen hair, features she inherited from a grandmother she believed was the daughter of a white slave mistress. Politically astute and terrifically self-possessed, Jackson felt comfortable around white and black people alike. Her parents were middle class, her father a Pullman porter with a law degree, her mother a homemaker whose beauty as a young woman so impressed Du Bois that he worried for her welfare among the men for whose family she worked as a domestic servant. “From my father and mother we had a sense of pride and a sense of who we were, that we must work to make things better.”33 Marvel was the first black student in her elementary and high schools and one of five black women at her university, cultivating a mix of ambition, kindness, and dauntless determination that launched her career. These qualities, along with an incipient political militancy, undoubtedly attracted Walrond. And she was a formidable intellect, a shrewd analyst of the imbricated workings of gender, class, and race well before the term “intersectionality” was coined. She coauthored a prominent exposé, “The Bronx Slave Market,” with Ella Baker.34

Jackson felt Walrond’s pride in his West Indian heritage. One day they noticed the cover photo of The Crisis featuring a Syracuse University track star and Walrond declared, “He’s West Indian.” Jackson replied, “Anytime anyone seems to have accomplished anything, you say they’re West Indian.” In this case, his claim was substantiated by a personal connection; his younger sister had dated this sprinter in Panama. Ironically, it was also the man Marvel Jackson would later marry, Cecil Cooke. “I had not met Cecil at this time” of the photo, “I was going around with Eric.” But later, when she started dating Cooke, she was certain Walrond had been wrong because “he talked very well” and without any “accent whatsoever that I could detect.” “I thought to myself, ‘Eric was certainly wrong about this one.’ But “after I had been going around with him about six weeks,” an inadvertent Britishism gave him away.

He said to me, “You like ice cream. You have never eaten any ice cream until you’ve had some Schroft’s Ice Cream.” We say “Schraft.” I looked at him. I said, “Are you West Indian?” Well, there was great prejudice then between West Indians and Americans. Americans didn’t like West Indians, you know, and vice versa. […] So I remember him saying to me, “Does it make any difference if I’m a West Indian?” And I said, “No” and I told him the story. “Eric said you were West Indian and I didn’t [hear] any trace of accent.” It turned out he was seven years old when his parents moved to Panama, and he grew up in the American sector.35

Jackson’s recollection illustrates Walrond’s abiding interest in the Caribbean. Cecil Cooke’s all but complete linguistic assimilation concealed his Caribbeanness from his companion, perhaps unintentionally. Walrond did not object to assimilation, but as an index of anti-West Indian animus, and as a symptom of monolithic notions of blackness, it underscored the necessity for West Indians to assert their distinctiveness even as they made the adjustments immigrants make to new environments. Cecil Cooke’s wayward vowel betrayed his ethnicity, compelling his future wife to admit, “It seems I was attracted to West Indians,” though she gamely added, “I didn’t know whether they were West Indian or not until I met them.”36 If her account of Walrond is to be credited, he later regretted their breakup.

COSMIC CONSCIOUSNESS

The community to which Walrond introduced Marvel Jackson had a more obscure component, a hidden transcript. In late 1925 he became involved in the work of the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man. Based on the teachings of G. I. Gurdjieff, an Armenian spiritualist, the New York initiative was led by Jean Toomer and A. R. Orage, former editor of the English journal The New Age. Gurdjieff’s philosophy was popularized in England in the early 1920s and, although it is unsurprising that it spread to New York given the trans-Atlantic traffic in avant-garde ideas, its foothold in Harlem was Toomer’s doing. Walrond did not write directly about the Gurdjieff “work,” but in this sense he was faithful to its teachings, which prized secrecy and kabalistic encryption. Several of Walrond’s friends were disciples while others were fellow-travelers, curious about Gurdjieff’s “system” for heightening consciousness. Toomer’s adaptation of Gurdjieff appealed to African American artists who felt confined by “Negro” identity. They sought full self-realization, something that the glacially slow shifts in race relations would not soon deliver but that Gurdjieff’s teachings promised through transcendence of racial thinking. Other participants included Thurman, Larsen, Fisher, Hurston, Douglas, Dorothy Peterson, and George Schuyler. Given Walrond’s relationships with them, his admiration of Toomer, and his desperate quest for psychological stability, it makes sense that he was drawn to this group. Beyond this circumstantial evidence, unmistakable traces of Gurdjieff’s philosophy appeared in his writing.37

The Gurdjieff “system” was mystical and messianic. It posited an antagonism between “false personality,” the insidious product of socialization, and one’s true “essence.” In Orage and Toomer’s version, it reserved a particular place for art, which could—if practiced with “objectivity”—transform creator and audience alike. The practice entailed lectures, role-playing, and physical and mental exercises, participants proceeding from novice to advanced stages with a dual aim: to experience themselves authentically, yet also to appraise themselves objectively through the eyes of the “other,” a technique called “self-observation and non-identification.” Muriel Draper, a friend of Van Vechten’s, convened meetings for Orage’s lectures, while Toomer’s group met in Harlem, Brooklyn, and Greenwich Village.38 Hughes satirized it as a “cult,” but he exaggerated when he said, “Nobody in Harlem could afford to pay for Gurdjieff. And very few there have evolved souls.”39 The group was active and large, notes George Hutchinson, “not, as often assumed, attractive only to white people with a large disposable income and plenty of spare time, although they ultimately depended on such.”40

Toomer gave a presentation at the 135th Street library in April 1925 that Walrond would have attended. Entitled “Towards Reality,” it praised the artistic renaissance and the Harlem issue of Survey, not as expressions of a racial inheritance but as evidence that “The Negro is in the process of discovering himself and being discovered,” removing the “crust” of received ideas. Thus would “the Negro” arrive at “reality” and encounter “that strange thing called soul.” But the “work” was not principally about race. As Aaron Douglas said, Toomer believed

We all have the potentialities of intellectual, artistic giants if we could only get to the bottom of our real selves. He claims that back deep in our natures there is a mine of unused power, a source, a hitherto little known faculty which is neither body, emotion or intellect, but is the equal and combined power of all.41

This helps explain the idiosyncratic formulations in an essay Walrond published the month of Toomer’s presentation. He referred to the emerging group of writers “utterly shorn” of a “negative manner of looking at life,” an echo of Toomer’s statement that “Because he was denied by others, the Negro denied them and necessarily denied himself. Forced to say nay to the white world, he was negative toward his own life.”42 Walrond said the younger generation refused to “put the Negro on a lofty pedestal” because “they don’t think of the Negro as a distinct racial type at all. They only write about him because they know more about him than anyone else. His is closer to them. He is part of them. As such they see him” (“Negro Literati” 33). The notion that the “Negro” was “closer to” and “part of” these authors presupposed nonidentity, characteristic of Toomer’s interpretation of Gurdjieff. When Nigger Heaven was published, Walrond was no longer close to Van Vechten, but his review of the novel referenced Gurdjieff explicitly. “[I]t prepares the way for examination of the fruits of a cultural flowering among the Negroes which is now about to emerge. And no colored man,” he concluded, “adept as he might be at self-observation and non-identification, could have written it” (“Epic” 153). These last were Gurdjieff catchphrases, elements of the curriculum of Toomer and Orage.43

“Adventures in Misunderstanding,” which Walrond published the same month, also made overt reference to Gurdjieff’s system. The essay ranges across color prejudices in Panama and the United States. “I believe the dicta to restrict the creative impulses of the Negro to the experiences of the blacks will be tempered by a tolerance and even a wish for transcripts of life more cosmically felt and conceived” (112). The statement curiously decouples the terms “Negro” and “black,” but Walrond meant that the expectation that “Negroes” confine themselves to the expression of racialization must be dismantled. His terminology sounded odd because it echoed Gurdjieff’s formulation of the stage beyond “self-observation and non-identification,” which was “cosmic consciousness,” the precondition for being “fully human.”44 Esoteric mysticism thus emerged in Walrond’s work, and for all its abstraction, it offered Walrond a way to negotiate something that had long troubled him: how to embrace his blackness without being considered, and considering himself, simply a “Negro.” Jon Woodson notes, “Toomer’s approach to the intricate problem was to paradoxically insist that African Americans had to disidentify themselves as African Americans, yet remain conscious that they were African Americans.”45 As a West Indian, Walrond had confronted this paradox well before the Gurdjieff group, if not on their “cosmic” plane.

The link between Walrond’s Caribbeanness and Gurdjieff’s principles was made in Wallace Thurman’s novel Infants of the Spring. Toomer advised his audience in 1925 to “be receptive of [the Negro’s] reality as it emerges, assured that in proportion as he discovers what is real within him, he will create, and by that act create at once himself and contribute his value to America.”46 The character Thurman based on Walrond, Cedric Williams, echoes this statement during a salon conversation. In response to claims by the Locke character and Cullen character that Negro writers succeed only by returning to “racial roots, and cultivating a healthy paganism based on African traditions,” Cedric poses what Thurman describes as an intriguing question.

What does it matter what any of you do so long as you remain true to yourselves? There is no necessity for this movement to become standardized. There is ample room for everyone to follow his own individual track. Dr. Parkes wants us all to go back to Africa and resurrect our pagan heritage, become atavistic. In this he is supported by Mr. Clinton. Fenderson here wants us all to be propagandists and yell at the top of our lungs at every conceivable injustice. Madison wants us all to take a cue from Leninism and fight the capitalistic bogey. Well … why not let each young hopeful choose his own path? Only in that way will anything be achieved.47

The remark reflects Walrond’s independent streak, but it clearly resonates with Toomer’s teachings on Gurdjieff. It was a philosophy toward which his incomplete identification with African Americans predisposed him, but it also registered his increasing suspicion of collective social action. Instead he had placed his faith in individuals working out their own spiritual destinies.

A PERSON OF DISTINCTION

Alain Locke wrote before Tropic Death, “Eric Walrond has a tropical color and almost volcanic gush that are unique even after more than a generation of exotic word painting by master artists.”48 And after Tropic Death his fame grew. It outsold Cane nearly two to one in these years and was among the most requested books at the 135th Street library when it came out.49 “One of the truly avant-garde literary experiments of the Harlem Renaissance,” says David Levering Lewis, it was “a prism so strange and many-sided” that few readers missed “its iridescence.”50 Walrond’s reputation was burnished by his association with Boni & Liveright, and Hughes and Cullen singled him out for public praise.51 Thurman said Walrond was among the few who deserved acclaim amidst a generally fatuous celebration: “There is one more young Negro who will probably be classed with Mr. Hughes when he does commence to write about the American scene. So far this writer, Eric Walrond, has confined his talents to producing realistic prose pictures of the Caribbean region. If he ever turns on the American Negro as impersonally and as unsentimentally as he turned on West Indian folk in Tropic Death, he too will be blacklisted in polite colored circles.”52 In fact, Walrond had just “turned on” them in the story “City Love.” A ribald tale of a young Harlem couple’s afternoon tryst, “City Love” was selected for the inaugural issue of The American Caravan. Edited by Van Wyck Brooks and Lewis Mumford, this was an annual compendium of modernist literature in which Walrond shared space with Hemingway, Williams, Stein, Dos Passos, and others. No longer a contestant, he now served as a judge for the Opportunity literary contest.

He still frequented Harlem’s cabarets, but a Friday evening was as likely to find him at the Lafayette Theater on 132nd Street or at the Provincetown Playhouse in Greenwich Village. Many of his friends were performers, and he was an enthusiastic spectator, attending Roland Hayes concerts and Paul Robeson plays, watching with delight the lithe-limbed Florence Mills, and enjoying the syncopated exuberance of Fletcher Henderson’s Rainbow Orchestra, the blues of Ethel Waters, and the stride piano of Willie “the Lion” Smith. He befriended the Trinidadian bandleader Sam Manning, who was Amy Ashwood Garvey’s companion and creative collaborator. Dinner parties abounded, from the opulence of A’Lelia Walker’s Italianate home in Sugar Hill to the modest apartments of Aaron Douglas on Edgecombe Avenue and of Dorothy Peterson in Brooklyn. Walrond threw parties too, though not every guest left contented; the Robesons attended a “little gathering” at Walrond’s that Eslanda found “a beastly bore,” just “some little insignificant talkative Negroes.”53 When the Fisk Jubilee Singers came to New York, Walrond joined Casper Holstein, who bought box seats at Town Hall.54

Certain functions were compulsory for an established writer who was also Opportunity’s business manager. In October 1926, Walrond joined dozens of Harlemites and a handful of white friends at the 135th Street YMCA for the Krigwa Players awards, a theater group started by Du Bois and colleagues.55 That spring he attended the annual meeting of the National Urban League. Funded by the Carnegie Corporation, the Urban League proclaimed “inter-racial Good Will” and 100 attendees heard from the governor of New York and the lead organizer of the American Federation of Labor.56 When the Comus Club, an elite group of black socialites, held its Christmas formal at the Savoy Ballroom, Walrond polished his spats and joined Cullen, Jackman, Bennett, Fisher, Walker, and Du Bois. As “Negro” society columns such as the Inter-State Tattler suggest, there were more benefits, ceremonies, and concerts than one could possibly attend, a professional hazard for Walrond.

Two of the livelier engagements fell within ten days of each other in October 1927, when the black-owned cabaret Club Ebony opened in Harlem and A’Lelia Walker opened “The Dark Tower,” an ostentatious tearoom overlooking the garden of her 136th Street home. Walrond arrived at Club Ebony with Marvel Jackson, meeting Aaron Douglas, whose murals adorned the club’s walls depicting “tropical settings, African drummers and dancers, a banjo player, and a cakewalker.”57 Douglas should have been thrilled but had just been summoned from the scaffolding by Charlotte Osgood Mason and upbraided for accepting a fellowship in Philadelphia.58 Walrond and Jackson also spoke to William Seabrook, a white novelist who would later write in support of a fellowship for Walrond. Equipped with a “spacious dance floor” and “large orchestra,” Club Ebony celebrated Florence Mills as guest of honor, with socialites pouring in from Atlantic City, Greenwich Village, Washington, and Philadelphia to toast a club that promised to retain the profits of black entertainment within the community.59

Celebrity had not made Walrond rich, however, and he continued living in his 144th Street apartment and working at Opportunity, which kept him busy. He was tasked with marketing the magazine and maintaining contact with subscribers, supporters, and advertisers.60 Sponsorship from Holstein expanded Opportunity’s awards program and their administration became a considerable undertaking. Advertising accounts required attention: Walrond wrote James Weldon Johnson to say he “had the distinction to prepare for the October Opportunity the advertising copy” for his Book of American Negro Spirituals.61 He was suited for the job, task oriented, and familiar with editors and publishers. But Charles Johnson felt that his business manager was also one of the few “Negro writers who can, with complete justice, be styled intellectuals,” and he sought a wider field for Walrond, nominating him for a Harmon Foundation Award in 1926.62 The prizes associated with the award were not insubstantial—$400 to the winner, $100 to runners-up—but its real significance lay in the distinction.

Walrond did not stand a chance his first time out. The Harmon Awards, funded by a white philanthropist from Ohio, recognized “Distinguished Achievement by Negroes” in eight fields, including literature. To administer the award, the foundation partnered with the Federal Council of the Churches of Christ in America, whose Commission on the Church and Race Relations was led by George E. Haynes, cofounder of the National Urban League. The Urban League connection may have encouraged Johnson to submit Walrond’s name, but he was outclassed. Nominees included Locke for The New Negro, Cullen for Color, Johnson for The Book of American Negro Spirituals, Du Bois and Charles Johnson for editorship of The Crisis and Opportunity, respectively, Hughes for The Weary Blues, and Charles Chesnutt, who was nominated for lifetime achievement. There was some question whether Walrond was eligible because Tropic Death was not due out until October.63 But he rushed the page proofs to Haynes in early August, and references were solicited from the vice president of Forbes, Donald Friede of Boni & Liveright, and Eugene Kinckle Jones of the Urban League.64 Awards committee chairman Joel Spingarn let it be known that he was not easily impressed. The younger generation’s literary achievements “have been grossly exaggerated,” he said. “A few minor poets and a few third-rate novelists are not a literature. The friends of the Negro, who have faith in his ability, would do him wrong if they were to give him a false impression of the literary work so far produced—not only a false impression but a false standard and a false hope.”65 The 1926 prizes went to Cullen and James Weldon Johnson.

Spingarn’s colleagues the following year were no less exacting, but it was their inability to reach consensus that ultimately landed Walrond an award. Indeed, given the impact of this award on subsequent events it is no exaggeration to say that the messy deliberations of these combative judges decisively altered the course of Walrond’s career. His selection was a compromise reached after a war of attrition over several weeks, phone calls, and telegrams. Surprisingly, Tropic Death’s staunchest advocate was the conservative critic and poet William Stanley Braithwaite. Joining Braithwaite and Spingarn among the judges were Henry Goddard Leach, editor of The Forum; Hamilton Holt, president of Rollins College; and Albert Shaw, editor of The American Review of Reviews. Had Haynes anticipated the rancor they generated he may have advised the foundation to redirect its philanthropy. The judges’ arguments remind one of the precariousness of events that over time acquire the appearance of inevitability. In order to win even the second prize of 1927 (first went to James Weldon Johnson for God’s Trombones), Walrond had to beat Arthur Huff Fauset, Georgia Douglas Johnson, Benjamin Brawley, Willis Richardson, and Alain Locke, among others, and he had to overcome the objection of one judge who would do almost anything to prevent him from winning.

Charles Johnson jeopardized Walrond’s candidacy by submitting his materials after the deadline, but the judges may have been persuaded to review the delinquent manuscripts upon reading the encomiums from his recommenders. Friede was the most knowledgeable and enthusiastic: “I have seen his first book of short stories, ‘Tropic Death’; half of his book ‘The Big Ditch,’ his treatment of the construction of the Panama Canal; and part of a novel which he will finish after the publication of ‘The Big Ditch’; besides various articles and short stories which have been published from time to time in periodicals.” “I believe him to be the outstanding Negro prose writer of this country,” he added, and “I believe that his work will in time place him among the important writers in America—both Negro and white.” Friede’s boss, Horace Liveright, also said he had known Walrond for two years and read Tropic Death, though it must be said that Liveright was notoriously inattentive to manuscripts, relying on the advice of established authors and contacts. He had read the first draft of The Big Ditch, he claimed, and praised “the beautiful style and excellent color which Mr. Walrond has employed in his writing, and the originality of his ideas.” He added, “I believe his writing to be the finest now being produced by any member of the colored race.” The novelist Joseph Hergesheimer said, “I have read Tropic Death, which seemed to me to be written with a fine sense of beauty and a respect for truth. […] He can write extremely well; what is more important he writes with courage; I think he has the ability to see honestly.” Asked why he endorsed the candidate, Hergesheimer said, “A sense of reality. The promise of dignity. Freedom from any bitterness or prejudice.”66 In fact, no one was bitterer than Walrond, but the lyricism and Caribbean setting of Tropic Death inoculated it against that charge.

While the judges deliberated, Walrond had other irons in the fire. Determined to make it as an independent author, he renegotiated his contract for The Big Ditch and quit Opportunity. Under the new arrangement, Boni & Liveright would pay a $500 advance in installments of $40 per week. This was more than double the original amount, but the contract stipulated, “As you complete the various portions of the manuscript, you will submit them to us for examination and for possible placing with magazines.”67 Serialization proved difficult, and although Walrond continued to publish other work, he probably missed the steady Opportunity paycheck. Johnson threw him a fine sendoff. “We are having a little informal dinner party,” he told Locke, “in the private dining room of Craig’s on Thursday, February 3d, for Mr. Walrond, who has resigned from the staff of Opportunity. We should like very much if you could arrange to spend your dinner hour there. No speeches; no dress regalia—just a friendly little party.”68 The Pittsburgh Courier covered his resignation, Walrond assuring the reporter “that he has good prospects for making writing a paying career.”69 Johnson paid glowing tribute.

In the resignation of Eric Walrond as Business Manager, Opportunity relinquishes from its staff one of the most brilliant of the younger generation of Negro writers. The duties of this department drew upon a skill less generally known to the public than his stories and essays, and it is a pleasing mark of well-rounded competence that artist and business man could be combined to the degree that he achieved. To his work, both in and out of the line of duty, Opportunity is indebted for new and valuable friends: he has been, perhaps longest of any of the younger writing group, successfully established in literary circles, although it was only last year that he offered a volume of stories to be published. […] Here is a ready index to the prodigality of talent and material which are so unquestionably a personal resource with him. Mr. Walrond was one of the first to sense the new public spirit on Negro aspirations and work, and contributed doubly, to a refinement of this public spirit and to the Negro aspirations. There are few young Negro writers in New York who do not associate some incident or personal discovery with his ceaseless, even if apparently unordered, activities. In withdrawing from the business department, there is the possibility and the hope that more time will be permitted for a field of writing in which he has already begun so magnificently to distinguish himself.70

Describing Walrond as a tireless organizer, an intellectual visionary, and a literary craftsman, Johnson stated his faith in Walrond. The Harmon Award would be a feather in the young writer’s cap, but it would also be a feather in the nest Johnson made at Opportunity, which had been Walrond’s refuge from the depression that two years earlier had him contemplating suicide.

The Harmon judging was muddled from the outset. Braithwaite put Walrond first and James Weldon Johnson second: “Walrond’s book is far more native to his own individuality; more original, and the power of his substance, and the artistic excellence of his style is of his own intimate creation. He is emphatically my choice for the award.”71 Leach and Shaw wanted Benjamin Brawley first and James Weldon Johnson second. As the year’s end approached, Spingarn attempted to forge consensus on this basis, but Braithwaite was obstinate. From a leafy suburb near Boston he wired the committee, “Cannot assent first award Brawley. […] Insist upon minority decision. First award to Eric Walrond. Agree second award Johnson.”72 Recognizing the impasse, Spingarn called Braithwaite on what he quaintly termed “the long-distance telephone.” The irrepressible Braithwaite persuaded Spingarn to his view, and Spingarn was compelled to write George Haynes, “We both agreed that Professor Brawley’s work was highly creditable, and deserved some sort of recognition, but that to award it a prize over two such creative works as God’s Trombones and Tropic Death would not cast credit on the Harmon Awards.”73 Thus, “after considerable discussion,” it was agreed that Johnson would receive first prize, Walrond second, and honorable mention to Fauset and Brawley. Shaw lobbied successfully to have Locke added to the honorable mention list, and the matter seemed settled. But Holt was unappeased: “I still vote for Georgia Johnson for First Prize and Richardson for Second,” or failing that, any combination “to prevent Brawley or Walrond from getting it. I would not vote for the two latter for anything.”74 Out of this tangle Spingarn somehow wove a compromise. Honorable mention went to Locke, Georgia Douglas Johnson, Brawley, and Fauset. Leach assented “under protest and only for the sake of arriving at a decision.” They had worn Holt down: “As long as the mountain will not come to Mohammed, Mohammed will go to the mountain,” he wired.75 The next day, Haynes wrote to notify Walrond of his award, omitting reference to the battle of attrition behind it.

Skepticism pervaded the New Negro movement toward the proliferation of awards—the “ballyhoo brigade,” Thurman derisively termed it. Walrond too felt white approval was not the goal, but he accepted the Harmon Award with unmitigated enthusiasm. “I cannot communicate to you the thrill I experienced on receiving your letter,” he told Haynes, “And to be cited on the same ‘ticket’ with Mr. James Weldon Johnson was also a distinction which I should not hope to under-estimate, ever.”76 He was now expecting notice about another major award. The Pulitzer Prize–winning dramatist Zona Gale funded a scholarship to bring impecunious writers of promise to the University of Wisconsin, and Walrond applied. A longtime friend of Opportunity, Gale had judged its fiction contests and had attended the 1924 Civic Club dinner, and she championed women writers, especially Fauset, Angelina Weld Grimké, and Georgia Douglas Johnson.77 She felt that the United States was tough on artists, and “if the artist is a Negro, his difficulties are needlessly greater in this country than in any other land of the civilized world.”78 She was moved by Walrond’s fiction, so it thrilled her to learn that he received the scholarship in her name.79 She pledged to have letters of introduction prepared for his arrival. Just three weeks after learning of the Harmon Award, in other words, Walrond decided to leave New York. The scholarship included a tuition waiver, “freedom in electing work in the University,” and a monthly stipend of $25. A modest sum, but he could now resume his bachelor’s degree and work with an esteemed faculty.

No record survives of Walrond’s reaction to this turn of events but it constituted a tremendous upheaval. The day after receiving official word of the scholarship, a letter arrived asking him to rush a photo of himself to Du Bois at The Crisis “for his use in connection with an article on the Harmon Awards.”80 The next day he boarded a train to Madison. The haste with which he arranged his departure is reflected in the confusion about the ceremony at which he would receive his Harmon Award. “Can you by any chance arrange presentation in Chicago?” he wired Haynes en route to Wisconsin, “Profoundly regret inability to change present plans.”81 Haynes had no trouble securing a place for him on the program in Chicago, scheduled two weeks later at the historic Olivet Baptist Church. The whirlwind culminated in a dash to Chicago for the ceremony. “I went up on a six thirty train, took my award at eight, and flew back to Madison on the two o’clock sleeper.” The event “went off splendidly,” he felt, and the proceedings were “not too long but direct and to the point.”82 Reports reached Haynes that Olivet was filled to the rafters with 2,000 attendees, the ceremony coinciding with the annual “Interracial Sunday” convened by the Council of Churches. “Speeches were made” and “telegrams were received and read,” including one from Countée Cullen.83 Walrond reflected, “Everybody seemed to be immensely pleased.”84

Little did he know how much more complicated things would soon become. Wisconsin faculty sought to identify “courses which will be directly related to [his] creative work” but this work was on Panama and required archival research. A novel manuscript was also in progress, but the Panama book was paramount. He had begun in earnest in January 1927, when he left Opportunity and renegotiated his Boni & Liveright contract. “On finding that I could not complete my researches in New York, I undertook, at the behest of the publishers, to make a trip to Panama early in the spring,” a four-week sojourn.85 The summer he devoted to writing, and in September, Bennett reported in Opportunity, “Who should I meet on the steps of the Forty-second Street Library the other day but Eric Walrond! He tells me that now that he has come back from Panama he is writing a book about that country … and I said how he surely ought to do just that!”86 But Walrond rushed the project, anxious to meet the publisher’s time line.

Returning to New York in April I was advised to prepare at once certain parts of the manuscript which might prove available for serialization. I prepared four or five chapters and sent them off to the agent. The narrative went the rounds of the editors but naturally did not “strike fire.” I attribute this to no inherent weakness either in the plan or texture of the book, but to the unleisurely fashion in which the preliminary parts had been prepared.87

The month in Panama persuaded him that The Big Ditch required additional research and inspired other projects. He applied for a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship to fund a year of travel in Latin America and the Caribbean. Within weeks of accepting the Harmon Award and Zona Gale Scholarship and moving to Wisconsin, he got word that he would be moving again.

THE GUGGENHEIM FELLOWSHIP AND THE BIG DITCH

A young “Negro” with one book out had a lot of nerve applying for a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1927. Of the foundation’s first 109 fellows, the vast majority had academic appointments and only three were African Americans.88 In its second year, the foundation received 900 applications, of which just seven were selected in creative arts. That this number rose to eleven in the year prior to Walrond’s application may have emboldened him, but he was a long shot. With a bequest of $3.5 million, the Guggenheim Foundation had ten times the budget of the Harmon Foundation and prestige of a different order. The selection committee included elite university administrators, and the director was Henry Allen Moe, who would become one of Walrond’s most faithful correspondents.89 The program’s self-image was lofty: “By setting the standards of qualifications up to the highest possible point, the Foundation would necessarily designate its Fellows as being superior men and women,” declared the first selection committee chairman.90

Walrond submitted a detailed research agenda and résumé, but he knew he needed impressive recommenders. He could not ask anyone like Casper Holstein, who supported his Harmon nomination, and the list he furnished included no African Americans: Donald Friede of Boni & Liveright; Robert Herrick, the novelist and University of Chicago professor who reviewed for The New Republic; Zona Gale; and the adventure novelists William Seabrook and William McFee, the first of whom was a notorious scoundrel, the latter an early mentor of Walrond’s who had managed within five years to forget him. Fortunately, Bob Davis of Munsey’s came to his aid with a glowing endorsement. Walrond announced his publications: “I have already written one book of short stories dealing with native life in the West Indies” and his second book, due in spring 1928, was the “first human interest account of the canal from the arrival of the French on the Isthmus in 1880 down to the opening of the canal in 1914.” The catalog copy read:

The building of the Panama Canal, that gigantic triumph of engineering over the most stupendous physical difficulties, lends itself to vivid telling as a human interest story. Strangely enough, though other accounts of the feat have been written, Mr. Walrond is the first author to bring out the drama of this as yet unsung epic of human heroism. He tells of revolutionaries, riots and the stirrings of racial consciousness among the varied nationalities engaged in the work. He tells of the titanic achievements of science, of human labor, of engineering. He describes the life and death battle against disease and insect pests which in that tropical climate present a more formidable front than armies of mere men. In this book, as in Tropic Death, the atmospheric quality is enriched by the author’s memories of his impressionable boyhood years spent on the Isthmus. The Big Ditch is a colorful and dramatic, yet careful and authentic work.91

Framed thus, The Big Ditch shared the “color” and “drama” of Walrond’s fiction but came with an assurance of historical fact.

He proposed now to return to fiction and folk cultures. “My object is to write a series of novels and short stories of native life in the West Indies,” emphasizing “the distinct racial and cultural composition of each island or group of islands.”

I propose delineating the peculiar quality of life current in the islands of Barbados, Jamaica, Trinidad, Cuba, and Martinique. While I should be anxious to allow no phase of life in the seaport towns and cities of the West Indies to escape my notice, I, however, think my desire would be to concentrate on the life and ways of the more primitive classes further inland. As I see it now the bulk of the material accruing from this study would resolve itself in terms of fiction, but it would be my plan to weave into this imaginative pattern a considerable amount of the legends, folk tales, peasant songs and voodoo myths abounding in this region.

The objective was “to interpret native life in the West Indies for the edification of people in the United States and Europe,” and as Herrick said in The New Republic, he had the field “quite to himself.”92

Herrick and Gale recommended him on the strength of his writing, while Davis, Seabrook, and Friede addressed his character. Herrick was “impressed not only with the creative ability of his stories but also with the grasp Mr. Walrond had of his material.”93 Gale felt that his substantial talent was poised upon greatness. Reading his submissions to the first Opportunity contest, she felt he “stood far above any of those entering fiction, and abreast of writers quite outside his class.”

His power was in the vigor, the clarity, the sweep of his style combined with amazing observation, and a certain accustomedness which seemed to belong to the Russians or the French.… But as I got into his manuscripts, I saw that he had not mastered his medium sufficiently to sustain a piece of fiction—he became powerless to direct his great gift, he lacked the knowledge and practice to find the flow of form. But all the time this great power over the minute, and this vigorous attack went on to the end. I recall that I said—though I could not vote for either of his stories for a prize—that if the contest had done nothing but to discover Eric Walrond, the effort and expenses were justified.94

Davis also suggested that racial background qualified Walrond for the proposed work but insisted that he offered something more: “Through education, application and a deep passion for self-expression in words he has come to understand the power of the English language and its interpretive value.” Over seven years “I have watched his progress in letters, printed much of his literature and read his entire output.”95

Donald Friede could only claim to have known Walrond half as long but was no less effusive.

Tropic Death I consider a fine, faithful and beautiful picture of the life of the negroes of the West Indies, and such portions that I have seen of The Big Ditch lead me to feel sure that this too will be a very important and beautifully written book. I can say with assurance that Mr. Walrond’s talents in this particular field are exceptional. I know of no one who can re-create life—in the regions he knows—as vividly as he can.96

Unlike the others, Friede and Seabrook sought to establish Walrond’s personal integrity. “I know him to be temperate and painstakingly scrupulous,” said Friede, “a diligent and conscientious worker who will leave no stone unturned to get the information that will make his material complete.”97

There is some irony in Walrond’s securing character testimony from Seabrook. An avowed proponent of the occult, he had purportedly eaten human flesh in Africa and had hosted Aleister Crowley, famous practitioner of “black magic,” at his Georgia home for two months.98 Having recently published a narrative of travels among Bedouin and Kurdish tribes, he would soon write books on the power of witchcraft, the zombie in Haitian vodou, and his own alcoholism, and he committed suicide by drug overdose in 1945. In recommending Walrond, he conceded that he may not be the finest judge of character.

I have known and sincerely liked Eric Walrond for a number of years. My wife, on whose opinion of character I depend more than my own, liked him instinctively at first sight, and almost from our first acquaintance we have counted him as our friend. [W]e have known him under a great variety of circumstances, in our home, in his, occasionally in the homes of mutual friends. He is one of the people, and I think there are many such, whom one seems to know intuitively is all right. I do not mean to imply that there is anything extraordinarily moralistic or saintly about him. I mean simply that he has a sort of fundamental integrity which is unmistakeable. I happen to like Eric Walrond very much—that of course is not necessarily connected with character; I like some people whom I wouldn’t trust around the corner—but Walrond is the sort of man I would trust and know was all right even if I happened not to like him.99

Moreover, Seabrook declared him possessed of “a peculiar creative spark which may perhaps be defined as potential genius.” “My feeling that he may go further and eventually become one of the truly great men of his race is shared by a considerable number of literary authorities who are not given to extravagant expression generally on such subjects.”100 The references had spoken; now there was the matter of the books themselves, which had not arrived at the foundation.

Walrond assured Henry Allen Moe that “a copy of Tropic Death, along with two scrap books containing comments and reviews concerning it, is being sent you today.”101 As to The Big Ditch he regretted “that the complete manuscript has not yet been delivered to the publishers.” His haste in circulating it for serialization had hampered its development; but he told Moe, “Since that experience, the book has undergone careful planning, and the material relevant to it jealously selected.” Moe had reason to wonder because The Big Ditch was publicized in Boni & Liveright’s Fall 1927 catalog and was announced in Opportunity that November.102 The book would never materialize, but the Guggenheim Fellowship did. Walrond got word from Moe a few short weeks after the Harmon ceremony in Chicago, his boxes still unpacked in Madison.103 “It is with the profoundest joy that I acknowledge receipt of your letter of March 13, 1928, notifying me that I have been appointed to the Guggenheim Fellowship,” he replied. “The opportunity is one that comes but once in a lifetime, and I assure you that I shall endeavor, by carrying out to the best of my ability the terms of this project, to merit the faith and confidence which have thus been reposed in me.”104 He presented himself to the Wisconsin General Hospital for physical examination. “A colored male, age 28, height 5 feet 10 inches, weight 138 pounds, whose general appearance is that of good health,” he was deemed fit to travel.105 Finishing the spring semester, he packed his things. Of the thirteen fellows in the creative arts, he was the only fiction writer and the only one not bound for France.106 Ironically, his Caribbean journey would end there anyway.

fter Tropic Death, things went so well that one wonders why Walrond left the United States. Why desert the country whose acceptance he sought? Why abandon Harlem as it emerged into prominence? Surveying 1926, Charles Johnson observed that “more books on the Negro have appeared than any other year has yielded, Broadway has welcomed three Negro plays, and with Eric Walrond, another Negro writer has moved definitely into the ranks of American artists with his fiercely realistic Caribbean tales.” His name appeared alongside Toomer, Hughes, and Cullen as writers of lasting import. “Eric Walrond automatically finds himself in this class,” said the Chicago Defender, “His stories will live as long as stories live.” There was no “discernible reason,” Robert Herrick felt, “why the creator of Tropic Death should not go much farther in this field, which he has quite to himself.”1

fter Tropic Death, things went so well that one wonders why Walrond left the United States. Why desert the country whose acceptance he sought? Why abandon Harlem as it emerged into prominence? Surveying 1926, Charles Johnson observed that “more books on the Negro have appeared than any other year has yielded, Broadway has welcomed three Negro plays, and with Eric Walrond, another Negro writer has moved definitely into the ranks of American artists with his fiercely realistic Caribbean tales.” His name appeared alongside Toomer, Hughes, and Cullen as writers of lasting import. “Eric Walrond automatically finds himself in this class,” said the Chicago Defender, “His stories will live as long as stories live.” There was no “discernible reason,” Robert Herrick felt, “why the creator of Tropic Death should not go much farther in this field, which he has quite to himself.”1