hen news reached Zora Neale Hurston that Eric Walrond and Countée Cullen were leaving on Guggenheim Fellowships, she dashed off an indignant note to Langston Hughes. “What, I ask with my feet turned out, are Countee and Eric going abroad to study? A Negro goes to white land to learn his trade! Ha!”1 Hurston could sniff, but unlike most Guggenheim Fellows, Walrond’s journey took him throughout the Caribbean. His award was trumpeted in the African American press and beyond.2 The Times of London noted that he was one of “three negroes” among the 75 fellowship recipients.3 Shortly before Walrond left for Panama, his first destination, V. F. Calverton wrote W. E. B. Du Bois that he was compiling The Anthology of American Negro Literature and felt Walrond was self-evidently among the short-story writers to include.4 The American Caravan also anthologized him, and The Negro in Contemporary American Literature credited him with having demonstrated “that the Negro may be judged as an artist with no special consideration because of race”5 (51). When the Encyclopedia Britannica prepared a fourteenth edition in 1928, the editors invited him to submit the entry on Harlem. In subsequent years, he would present versions of this entry to audiences from Barbados and the Virgin Islands to Paris, Madrid, and London.6

hen news reached Zora Neale Hurston that Eric Walrond and Countée Cullen were leaving on Guggenheim Fellowships, she dashed off an indignant note to Langston Hughes. “What, I ask with my feet turned out, are Countee and Eric going abroad to study? A Negro goes to white land to learn his trade! Ha!”1 Hurston could sniff, but unlike most Guggenheim Fellows, Walrond’s journey took him throughout the Caribbean. His award was trumpeted in the African American press and beyond.2 The Times of London noted that he was one of “three negroes” among the 75 fellowship recipients.3 Shortly before Walrond left for Panama, his first destination, V. F. Calverton wrote W. E. B. Du Bois that he was compiling The Anthology of American Negro Literature and felt Walrond was self-evidently among the short-story writers to include.4 The American Caravan also anthologized him, and The Negro in Contemporary American Literature credited him with having demonstrated “that the Negro may be judged as an artist with no special consideration because of race”5 (51). When the Encyclopedia Britannica prepared a fourteenth edition in 1928, the editors invited him to submit the entry on Harlem. In subsequent years, he would present versions of this entry to audiences from Barbados and the Virgin Islands to Paris, Madrid, and London.6Walrond’s departure has been seen as the beginning of his end, an unraveling. It marked a decisive break from the exuberance of Harlem, and he would never be as prolific again. But he does not seem to have had misgivings, nor did he express regret later. Leaving the United States enabled a distinctive new sensibility, a critical cosmopolitanism. As he traveled, first in the Caribbean, then to France and England, his work came to exhibit a form of border thinking, an effort to articulate the disavowed links between modernity and coloniality.7

The seeds were sown before Walrond’s departure for problems later attributed to his exile. Shortly after receiving the Guggenheim award, he wrote Boni & Liveright that he was “down to my last buck” awaiting his royalty check.8 Opportunity reported that The Big Ditch was about to be published, but the announcement was premature; not only was the manuscript prepared too hastily, Boni & Liveright was beset with trouble.9 Vice President Donald Friede was negotiating a buyout, and the firm was in dire financial condition. Horace Liveright and editorial director T. R. Smith had just been acquitted of obscenity charges for publishing a salacious Maxwell Bodenheim novel, but Friede still faced obscenity charges for selling a copy of Dreiser’s An American Tragedy in Boston. Liveright’s wife was suing for divorce, and he was badly injured in an inebriated fall from an open car.10 The vice president for production and sales, Julian Messner, wanted to unload Walrond’s book on Friede, who was forming a new company. Nothing suggests that Walrond was consulted or notified.

“Friede had me on the phone this morning,” Messner wrote Liveright, “He is willing to take over ‘The Big Ditch.’” Then Messner revealed something astonishing. “I rather think you will be for this, even though we have not yet seen the manuscript nor been able to judge its value.” The book had been acquired, edited, and announced without review from the firm’s highest officers. More than $200 had been dedicated to advertising and $1,000 advanced to the author. A month before Walrond embarked for the Caribbean, Liveright assented to the plan, stipulating that Friede must “give us cash down for what we have advanced, together with our expenses.”11 This arrangement would not be realized, however, and The Big Ditch would languish with a firm that no longer wanted it, its author laboring to improve it from abroad while clouds gathered for an economic collapse so catastrophic as to decimate the book business.12

AWESOME THERAPY

The new returnee, as soon as he sets foot on the island, asserts himself; he answers only in French and often no longer understands Creole. A folktale provides us with an illustration of this. After having spent several months in France a young farmer returns home. On seeing a plow, he asks his father, an old don’t-pull-that-sort-of-thing-on-me peasant: “What’s that thing called?” By way of an answer his father drops the plow on his foot, and his amnesia vanishes. Awesome therapy.

FRANTZ FANON, BLACK SKIN, WHITE MASKS (1952)

Walrond left New York in late September 1928 with two letters of introduction. One was from novelist William McFee, recommending him to H. G. De Lisser, the most important literary figure in Jamaica, a novelist and editor of The Gleaner. Another was a general letter from Henry Allen Moe of the Guggenheim Foundation recommending Walrond “to the estate, confidence, and friendly consideration of all persons.”13 His ship arrived at the Canal Zone six days later. What is known of Walrond’s experiences during this period comes chiefly from letters to Moe. Some of the texture of his experience is therefore lost in the official cast of the correspondence. His trip took him from the Central American coast to the Windward and Leeward Islands of the Caribbean. He delivered a few presentations, and visits to Panama, Haiti, and Barbados germinated material for new projects. They would not come to fruition in book form, as he hoped, but they reflected his growing concern with a new form of imperialism in the service of U.S. corporate and military interests.

The canal had been open fourteen years, and although many West Indian laborers stayed after its completion, many more returned to the islands or headed north to the United States and Cuba. Those who remained faced tough conditions; by 1924, there were 20,000 unemployed “Negroes” in the Canal Zone. The expansion of U.S. territory continued apace, with increasing militarization and the expropriation of more than 4,000 acres of land for canal defense and military posts. An average of 7,400 U.S. troops occupied the Canal Zone during these years.14 Walrond had proposed “to concentrate on the life and ways of the more primitive classes further inland,” but these new Panamanian conditions led him to reformulate his plan. Foul weather frustrated his goal of visiting the indigenous people displaced by the canal construction. As well, “disturbances” in the Chiriquí District near the Costa Rica border caught his interest. Social unrest had arisen, he said, from “the introduction of West Indian Negro laborers on the banana plantations of a subsidiary of the United Fruit Co.”15 Chiriquí was a United Fruit stronghold under watchful U.S. military protection. By 1913, the company held nearly a quarter of all private property in Panama, and by 1920, its holdings included 250 miles of railways and 46,000 acres of agricultural land.16 The U.S. military presence grew in Chiriquí over the express objections of Panamanian officials. Conditions there and the fallout from the U.S. occupations in Haiti and the Dominican Republic forestalled any patriotic reverie in which the proud Guggenheim recipient may have indulged. There was also the matter of The Big Ditch, still incomplete. Part of his “quest” was to “verify in the Government Library at Balboa Heights certain researches which I had previously made into the history of the Panama Canal.”17 It is likely he did more than verify, for the holdings included The Canal Record, the published reports of the Isthmian Canal Commission (ICC), and local English- and Spanish-language periodicals. Having intended to stay through November, Walrond did not leave Panama until mid-December. It took four days for him to reach Haiti, and four thereafter to reach age thirty.

Cracks were forming in the U.S. occupation of Haiti, imposed in 1915, and a year after Walrond’s visit the conflict would sharpen, compelling presidentially appointed U.S. investigative commissions to recommended withdrawal. “In the three months that I spent on the island I had exceptional opportunity to study the Occupation from both the American and the Haytian side,” Walrond wrote, “Out of the curiosity that took me to Hayti, I ultimately emerged with the material for two books.” The first was to be a study of the aftermath of the Haitian revolution, which abolished slavery and effected independence from France, but not without tremendous loss of life and social upheaval. He felt that “the numerous revolutions that have taken place in the history of Hayti” could only be understood by “studying the underlying causes.”18 He proposed to title the book The Struggle for Representative Government in Hayti from the Creation of the Black Republic in 1804 to the American Intervention in 1915.

Walrond knew something few North Americans recognized at the time but many historians now grant: “The history of social revolution in the Western Hemisphere starts not with Lexington and Bunker Hill in 1775, but less auspiciously in the French tropical colony of Saint-Domingue in the Caribbean.”19 The intricate alliances and conflicts among the “small whites,” the elite plantocracy, the French government, the enslaved, and the free people of color were, Walrond realized, as dramatic a tale of modernity as one could tell. Saint-Domingue slavery was as brutal as anyplace in the hemisphere, and the triumph of Toussaint L’Ouverture and the reversion to despotism under Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Henri Christophe were momentous events, the significance of which few North Americans appreciated. Having defeated one colonial regime, Haitians’ quest for autonomy amid the competing claims of France, Germany, and the United States was a matter of considerable concern among African Americans. James Weldon Johnson, for example, was no radical, but he wrote penetrating critiques of U.S. policy in Haiti in The Nation in the early 1920s. Walrond was undoubtedly familiar with Johnson’s account and possibly with Dantès Bellegarde, a Haitian intellectual who spoke against the U.S. occupation at the Fourth Pan-African Congress in New York.20 But his most likely interlocutor on Haiti was Hubert Harrison, who wrote regularly on the subject when they worked together at Negro World. “Here is American imperialism in its stark, repulsive nakedness,” Harrison bellowed, “And what are we going to do about it?”21

Walrond formulated his proposal to Moe, challenging the official narrative that justified the occupation.

I have decided, out of the welter of material I have acquired, to address myself to the Revolt of the Cacos. The cacos were supposed to be “professional bandits” who infested the hills of Hayti during the early years of the American Occupation, but there is concrete evidence to prove that on the contrary they were peaceful peasant farmers who were forced by the abuses perpetrated under the corvée to take up arms in defense of their dignity and integrity.22

Although the occupation improved Haiti’s infrastructure, health care, and education system, staggering force was required to put down popular resistance. The corvée was a forced labor system, and the gendarmerie, supervised by U.S. officers, abused laborers, “forced them to march tied together by ropes, and made them work outside their own districts for weeks or even months. Haitians resented these practices, which recalled French slavery.”23 The conflict came to a head as the cacos, defeated in the U.S. invasion of 1915, regrouped, overthrew the gendarmerie in the northern highlands, and threatened Port-au-Prince. “From March 1919 to November 1920, the marines systematically destroyed the rebels, using, for the first time ever, airplanes to support combat troops,” killing more than 3,000 Haitians.24 With Haiti still occupied, Walrond sought to confront the prevailing view of the resistance as “professional bandits” and the Americans as a benign shield against European intrusion and internecine warfare.

From Port-au-Prince in January 1929, Walrond applied to the Guggenheim Foundation for a one-year extension “to carry out this program with a minimum of anxiety and the utmost independence.”25 By the time Moe replied, Walrond had left Haiti for the neighboring Dominican Republic. The foundation’s response was not all bad, a six-month extension through spring 1930, but Walrond had overlooked a vital element in proposing to return to New York—appointments were for overseas projects only. Thus Moe stipulated something with fateful implications: “The grant made you is not available for work in the United States.”26 Making the extension conditional on Walrond’s absence from the United States, the foundation kept him abroad during the country’s worst financial crisis and in so doing propelled him to Europe.

Walrond’s remaining months in the Caribbean entailed stops in Puerto Rico, St. Thomas, St. Kitts, and Barbados. At least twice, he was able to enjoy his celebrity, delivering speeches about his career in New York. He spoke in St. Thomas at an event reported in the Chicago Defender and in the Virgin Islands newspaper The Emancipator.27 Walrond was asked “to put aside all modesty and to give a full account of himself and the obstacles with which he has had to contend in his climb to fame.” His address was more sociological than literary. On moving to New York, he explained

[It had been] necessary to maintain his individuality as a West Indian, as all his family were West Indians. Later, however, when he began to travel he found that he was different, both in thoughts and habits from the West Indian. He was an American in thoughts and acted like one. He could not adapt himself to the feudal system which still obtains in most West Indian Islands, and to which the inhabitants are accustomed.

It sounds as though Walrond may have been supercilious, evincing pride in his American identity and the American way of life, which he depicted as a color-blind meritocracy. “He recited the progress of the Colored race and the money accumulated by it. He told of colored bankers, orators, poets, musicians, authors, and so on, and how they did things, not as colored people, but as Americans, forgetting the color question entirely.” Surely this overstated the contrast between West Indian “feudalism” and American egalitarianism, and it was a polite fiction to claim that African Americans were “forgetting the color question entirely.” Perhaps he felt he was living the American Dream and thus trumpeted its democratic promise. But he may have meant to convey something more nuanced about the psychological distance he had traveled that was lost in translation between places. The Emancipator declared, “Personal contact with men such as Mr. Waldron [sic] will have the effect of setting us thinking and may eventually open to us the great possibilities that are ever before us.”

A more developed literary community was forming in Barbados, where he arrived in April. The Forum Club, a new organization, invited him to speak on “Some Writers of the Negro Renaissance.” Composed primarily of “educated professional black and coloured men, many of whom held or would assume leadership roles in the society,” the Forum Club became an important venue for fostering a literary community in Barbados and beyond.28 It launched a journal, The Forum Quarterly, in 1931 and hosted notable figures, including C. L. R. James, who spoke about crown colony government just before leaving for England in 1932. Barbadian scholar Carl Wade considers The Forum Quarterly a springboard for the better-known journal Bim, founded in 1942.29 It is remarkable to consider Walrond’s return to Bridgetown, his boyhood home, during this formative period.

En route to Barbados, Walrond had devised a plan to meet the terms of his fellowship. He would “wind up work in the West Indies” by late May, he said, then “journey on to Europe where I shall settle down to a siege of writing.” The plan prevented him from accepting an invitation to deliver the keynote address at the Negro Progress Convention in British Guiana in July. An association with roots in the Garvey movement, the Negro Progress Convention hosted speakers from the Caribbean and North America, and although Walrond declined the invitation, he suggested in his place the Reverend F. G. Snelson, director of missionary work for the African Methodist Episcopal Church, whom he met on the boat to Barbados. When Snelson addressed the convention, he began by thanking Walrond, calling him “a wonderful little man […] with athletic form and cultured brow” and praising his inquisitiveness. “He is a student, a young man of promise, and I declared to him that he owed it to South America when he finished his work to go back and found a University,” a remark that elicited applause. Walrond had assured Snelson that “he had not forgotten the debt he owed to his native land.”30

Despite the praise and attention, Walrond grew concerned as the end of his fellowship approached that the foundation might not be satisfied. He had not informed Moe of “the progress I have made in creative writing,” he realized, because “most of my time has been spent in research and organization.” Already a flicker of apprehension crept in. “It is with a full consciousness of the gap left to be filled in that I propose, unless it conflicts with the wishes of the Foundation, to proceed to Europe and devote myself entirely to developing the plans I have formulated for creative and other writing.”31 His difficulty with The Big Ditch was no secret among his friends in Harlem, though they did not understand it.32 In a rant that was probably lubricated with gin, Wallace Thurman wrote Langston Hughes in 1929, prescribing cynical remedies for problems plaguing their peers, recommending that Jessie Fauset “be taken to Philadelphia and cremated,” Countée Cullen “be castrated and taken to Persia as the Shah’s eunuch,” and “Eric ought to finish The Big Ditch or destroy it.” (For himself he recommended suicide, which was sadly not far from his alcoholic fate.)33 Finish it or destroy it: sound advice, but it went unheeded. For a number of reasons the project instead splintered into multiple versions and revisions. Not the least of them was an unsupportive publisher, a problem that worsened in subsequent months. One might also conjecture that the self-confidence Walrond had mustered to see Tropic Death into print was no longer available. But there is no evidence that severe depression returned until 1931. The problem with The Big Ditch was as much one of form as external circumstances.

The book was conceived as a project of cultural mediation, a Panamanian history for North American readers. “[T]hough other accounts of the feat have been written, Mr. Walrond is the first author to bring out the drama of this as yet unsung epic of human heroism,” promised Boni & Liveright.

He tells of revolutionaries, riots and the stirrings of racial consciousness among the varied nationalities engaged in the work. He tells of the titanic achievements of science, of human labor, of engineering. He describes the life and death battle against disease and insect pests which in that tropical climate present a more formidable front than armies of mere men. In this book, as in Tropic Death, the atmospheric quality is enriched by the author’s memories of his impressionable boyhood years spent on the Isthmus.34

Memory is a funny thing though, and a return to the Caribbean complicated the romance of “romantic history,” challenging his intentions. Walrond’s letters suggest new layers of feeling and awareness, an encounter with U.S. imperialism shorn of the fig leaf of civilization.

If he had come to do some fact checking, visit the indigenous people, and turn folklore into short stories, Walrond instead found a welter of labor problems and militarization, democracy attenuated, and popular resistance discredited as lawless banditry. In short, the fellowship that represented such comfort placed him onto the horns of the formal dilemma of the colonial intellectual. Cosmopolitan projects emerge from the perspective of modernity, Walter Mignolo has said, while critical cosmopolitanism emerges from modernity’s constitutive exterior, coloniality. Which sort of book was The Big Ditch? How could a manuscript conceived in the cosmopolitan tradition to delight and instruct be made to accommodate a sensibility “issuing forth from the colonial difference”?35 In 1922, Walrond had taken a therapeutic return trip to the islands, a prescription filled by his voyage as the cook’s helper aboard a United Fruit steamship. But this subsequent Guggenheim journey had been “awesome therapy” in Frantz Fanon’s sense, as blunt a reminder of Caribbean conditions as the plow dropped on the foot of the farmer’s son returned from France.

FRANCE

He wrote me quite some long letters telling me about his experiences in going to France and living on the Riviera, of accidents he had had, and his life being very turbulent in through there. But for some reason he was never very anxious to return to the United States.

ETHEL RAY NANCE (1970)

A generation later, London would have been the West Indian intellectual’s destination, but this was long before the Caribbean Artists Movement, before the postwar Windrush generation. Black Britain was an oxymoron in 1929; it was only comfortable to be a person of color in England for entertainers, and even they felt uneasy once the curtain closed and the applause subsided.36 J. A. Rogers, covering Europe for the New York Amsterdam News, called England “the only European country in which one is likely to find color prejudice.”37 France was known to tolerate social difference, and Paris had acquired such a fondness for African Americans that Ada “Bricktop” Smith, cabaret performer extraordinaire, called the phenomenon la tumulte noir. Friends told Walrond the city was enchanting. “There never was a more beautiful city,” said Gwendolyn Bennett, who studied there in 1925, “On every hand are works of art and beautiful vistas … one has the impression of looking through at fairy-worlds as one sees gorgeous buildings, arches, and towers rising from among [the] trees.”38 Cullen, whom Arna Bontemps called “the greatest Francophile,” was staying in Montparnasse, near the Latin Quarter.39 Walrond knew musicians, singers, actors, and pugilists who had taken a turn in the Paris spotlight and reporters sent there on assignment, and although their opinions were not uniformly positive, the consensus was clear: “There you can be whatever you want to be,” as Langston Hughes said, “Totally yourself.”40 When Walrond’s ship from Barbados docked in London, he left immediately for Paris.41

A special legend had grown around Montmartre, a district in which many clubs and restaurants were operated by black owners, featured black entertainers, and served a predominantly black clientele. A steep tangle of cobblestone lanes near the Sacre Coeur cathedral, Montmartre was frequented by avant-garde modernists but was also hospitable to African Americans. When Hughes arrived in 1924, a sailor with seven dollars in his pocket, he was told “most of the American colored people […] lived in Montmartre, and that they were musicians working in theaters and night clubs.”42 The cabaret where he washed dishes, the Grand Duc, was far from grand—“the size of a single booth at Connie’s Inn”—but it became the cornerstone of Montmartre jazz.43 In many ways, Montmartre was France’s answer to Harlem. But as the decade wore on, “hot jazz” was popularized and venues like the Grand Duc became trendy destinations for white patrons—the avant-garde, bon vivants, and, more perniciously, Americans intent on curbing the association of white women with black men.44 Black Montmartre also faced the “ten percent law,” legislation aimed to keep French nationals employed, limiting the number of foreign musicians an establishment could hire. Thus, although it was Harlem’s nearest equivalent, Montmartre was no longer the obvious destination for Walrond by 1929.

Instead he moved to Montparnasse, a choice that had less to do with its association with artists and intellectuals than the more practical consideration that Countée Cullen lived there. Cullen seems to have put him up until he found his own lodgings. Although Cullen was well known on the Left Bank, he preferred “the detachment of his studio out Montsouris way.”45 Montsouris, a park at the edge of Montparnasse, was a bucolic retreat from the grand boulevards and bustling cafés. Only one letter survives to document Walrond’s residence there, but it is corroborated by a Paris Tribune column.46

Eric Walrond, another Guggenheim scholar, is living with Countée Cullen. He is hard at work on his next novel, which we hope will be as interesting as Tropic Death, published a couple of years ago. Walrond […] has traveled extensively but considers the Left Bank the bright spot of the cultural world. “Its traditions and literary associations,” he says, “stimulate the best efforts in one. Here one can find variety or peace.”47

Peace was the Parc Montsouris, where Hemingway sent his star-crossed lovers in The Sun Also Rises, a place whose “budding trees” Cullen “could see every morning from my window and whose leaves I could hear each night sighing and soughing in the wind.”48 Variety, on the other hand, was the social whorl, continually rejuvenated by fresh arrivals. “When Walrond isn’t busy at work,” a reporter noted, “he stops in, on occasion, at the Dôme, where he meets a number of his friends.”49 Meeting friends at Left Bank cafés was a time-honored ritual, and Walrond found no shortage of either friends or cafés.

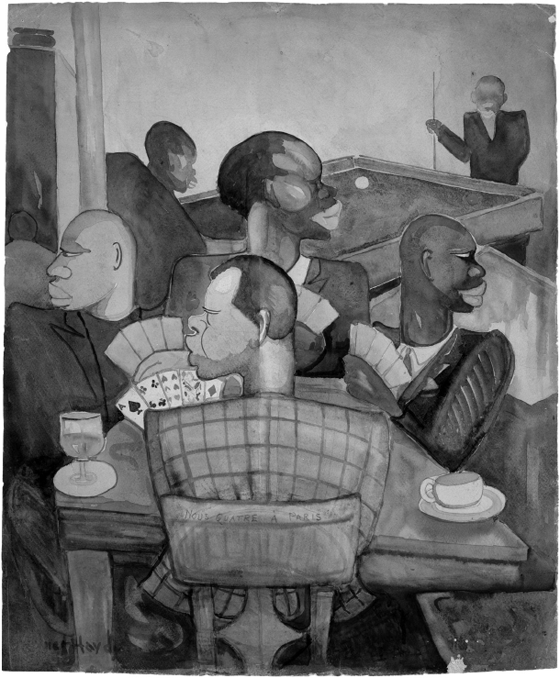

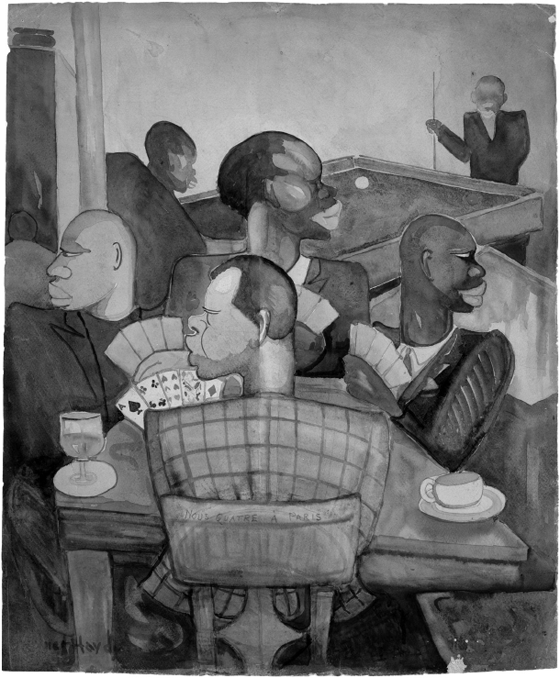

He particularly enjoyed the Dôme and Café Capulade. With its “elaborate zinc bar, marble tables, leather banquettes, and mirrored walls,” the Dôme was also a favorite of Henry Miller, Man Ray and Kiki, and Hemingway. Walrond often met the painter Palmer Hayden, “tall, dark, and looking more like an English gentleman than like the proverbial painter,” Cullen said, “shining out like a bit of ebony from among the other habitués of the Dome.”50 Invariably, Hayden’s friend Hale Woodruff, a painter and recipient of a Harmon Award, accompanied them. Sequestered in a back room were the billiard and card tables this group preferred. “Eric Walrond … we used to play cards together all night in the cafés in Paris,” Hayden recalled, “There’s a part of the cafés there … set aside especially for people who want to play cards, not gambling but checkers and chess […] so we’d hang out there, Countée, another West Indian, Dr. Dupré, all of them students.”51 Hayden’s watercolor Nous Quatre à Paris depicts their activity, and although they are not identified, the figures likely represent Hayden, Cullen, Walrond, and Woodruff. The cafés were also for catching friends up on the previous night’s activities. After one evening of carousing and drinking with friends, Walrond got stuck with the tab, and when he could not persuade the owner to accept a personal check or even his watch in partial payment, he was thrown in jail for the night. Recounting the story to Harold Jackman at the café the next morning, Walrond was less amused than his friend, who replied wryly, “I didn’t know anything new could happen to you.”52

Beyond its bohemian sophistication, Montparnasse had something else unrivaled in Paris, the Bal Nègre. Also known as the Bal Colonial, it was a little gem of a dance hall where Walrond’s friends brought him the night he arrived, July 5, 1929. It had quickly become a preferred destination of the American “Negro colony,” but its appeal lay in the diversity of its patrons. It was “probably the most cosmopolitan and democratic dance hall in Paris,” Cullen said, “which may mean in the world.”53 No sooner had Walrond arrived than he was swept into a delirious week of festivities, punctuated by an Independence Day celebration and a night of carousing, including the Bal Nègre. The occasion was a birthday party for Louis Cole, the pianist at Bricktop’s and a singer in the popular revue, Blackbirds. Hosted in a “magnificent mauve apartment near the Trocadéro,” Cole’s party featured torch songs from Zaidee Jackson and dancing by the Berry Brothers, costars in Blackbirds. Walrond may have been surprised to find his old friend Van Vechten among the revelers, who also included “two counts and a princess.” He left with Cullen, J. A. Rogers, and a few others for Zaidee Jackson’s apartment in the Champs-Élysées, then to the Bal Nègre “to complete the week of fun.” “Our group can do a mean bout of ringing and twisting,” wrote Rogers, “along with the Martiniquans doing their delightful dance—the beguine.”54 This was quite a welcome.

7.1 Palmer Hayden, Nous Quatre a Paris (We Four in Paris), watercolor and pencil on paper, c. 1930.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The reference to the Martiniquans and the biguine underscores another distinctive quality of black Paris, something the Bal Nègre crystallized: its heterogeneity. Stepping through its doors, Walrond would have experienced something uncanny, a bit like Harlem and a bit like the Caribbean yet more than the sum of its parts. Harlem’s New Negroes were plentiful but émigrés from Guadeloupe, Martinique, and Haiti set the tone and the tempo. “As an American Negro we are somewhat startled to find that our dark complexion avails us nought among these kindredly tinted people,” wrote Cullen, “Language must be the open sesame here, and it must be French.”55 Despite the awkwardness, Cullen enjoyed the Bal Nègre more, he once admitted, than his beloved opera. “The visitor who speaks only English had better take his interpreter with him,” Rogers concurred, for “the majority of the Negroes come from the French West Indies or parts of Africa.”56 Eslanda Robeson became intrigued by the Pan-Africanist promise of black Paris as exemplified by the Bal Nègre, publishing a two-part essay in Dorothy West’s journal Challenge. For Walrond, this milieu was familiar yet wonderfully strange: a community of “Negroes” that not only accommodated but affirmed intraracial differences. Unlike in New York, “Negro” was not synonymous with African American in Paris, and Montparnasse alone was home to nearly one thousand former Caribbean residents. Paris thus expanded and complicated African Americans’ perspectives on race, introducing them to Antilleans and Africans, from the elites of Guadeloupe who strolled the Sorbonne speaking with Parisian accents, to Senegalese sailors who had joined France’s military in World War I.57 The confluence of people of African descent inspired more than dance hall meditations. The intellectual life of Pan-Africanism, galvanized by the 1919 Pan-African Congress, would soon flourish in Paris in the 1930s. Its most celebrated expression was the Negritude movement, led by Aimé Cesaire, Léopold Senghor, and Léon Damas, a movement that wed anticolonial politics with surrealism and Marxism.

But the seeds were sown for Negritude—and indeed for alternative modes of black transnationalism—during the period in which Walrond lived in Paris. In the 1920s, several African American intellectuals nurtured connections with French periodicals, engaging in translation and scholarship. The journals Les Continents and La Depeche africaine cultivated a transnational sensibility and artistic aspirations among France’s black intellectuals. A brilliant Martinican student, Paulette Nardal, published regularly and hosted a salon with her sisters, Jane and Andrée, and their cousin Louis Achille. In 1931, she founded a bilingual journal, La Revue du monde noir, with the Haitian expatriate Léo Sajous. She was the most important connection between the U.S. New Negro movement and Negritude, an exceptionally gifted “intermediary.” The Nardals shared so many contacts with Walrond as to make their meeting seem certain. Paulette introduced René Maran and Senghor to Claude McKay, Mercer Cook, and Carter Woodson, all of whom Walrond knew, and to his friends Cullen, Locke, and Woodruff. They were familiar with Walrond’s work; Jane was a self-described “lectrice assidue” (“assiduous reader”) of Opportunity, and she and Paulette translated The New Negro. The intervention they made would have been of great interest to Walrond: “Unlike the Francophone literature in the 1920s, La Revue du monde noir conceive[d] black culture as an autonomous and transnational tradition rather than a subset of colonial history.” Paris salons are the stuff of legend, but these black intellectual spaces were distinct from the salons of “Lost Generation” modernists. They constituted a different counterculture to modernity because theirs involved colonialism centrally.58

Walrond was not in Paris just to dance and attend salons, however; he had plans for a novel, other projects conceived in the Caribbean, and of course The Big Ditch. At the National Archives he reviewed records and press coverage of the failed French attempt at the canal. Count Mathieu de Lesseps, the youngest surviving son of the project director, granted him an interview. After Walrond’s lunch with the count and his wife at their apartment near the Arc de Triomphe, de Lesseps spoke ruefully about “the Panama affair,” which ruined his father emotionally and financially. The countess translated her husband’s account for their visitor.59 It was a tale of calumny and deception, the story of a bold patriot, renowned for his direction of the Suez Canal, brought low by corrupt officials and an unscrupulous press corps. “The Government had to find scapegoats in order to save itself and clear the real culprits,” explained the younger de Lesseps. Walrond did not believe much of it, but on the basis of this narrative and his research in the National Archives he wrote an essay, “The Panama Scandal.” It appeared in the Madrid journal Ahora, titled “Como de Hizo el Canal de Panama” (“How the Panama Canal Was Made”).

André Levinson did Walrond a good turn by publishing a puff piece in the weekly Les Nouvelles Littéraires soon after his arrival in Paris. Levinson’s discussion of Tropic Death appeared between remarks on McKay’s Banjo and Toomer’s Cane. He criticized McKay for overreliance on “standard literary devices” but called Walrond a “determined artist whose concise, condensed tales of repressed passion unravel tragic themes against a glowing background of tropical magic.” Levinson found Walrond’s dialect “charming in its mellowness, [a] flavorful and melodious mixture.” Whereas Cane was “a collection completely amorphous” and Banjo a “boneless piece [with] the inconsistency of a mollusk,” Levinson thought Tropic Death exhibited formal coherence. Walrond’s “bitter impassiveness” made it “the blackest book (no pun intended) that American literature has produced since the Devil’s Dictionary by Ambrose Bierce.”60 In keeping with this coverage, a drawing of Walrond accompanied the article despite being less famous than McKay and Toomer. He appears brooding, staring fixedly with brow knit under a receding hairline. The image contrasts markedly with a drawing of Walrond published two months earlier in The Clarion, a London monthly. This image, featuring a casual smile, a three-piece suit, and a kindly gaze at the viewer, accompanied Walrond’s article, “The Negro Renaissance.” The article and drawing were reprinted the following month in the Jamaica Gleaner, and one wonders whether Edith Cadogan had a shock that Saturday in August, opening the newspaper to find the genial visage of her estranged husband peering back.

Although it included an abbreviated history of the movement named in the title, “The Negro Renaissance” was really a review of Banjo. Walrond credited McKay with having sparked the “cultural rebirth” in Harlem but lamented McKay’s long absence, the result of which was a tin ear for dialogue. Walrond appreciated the “cesspool of bums, coke sniffers, perverts, wharf rats, and jobless seamen” that McKay assembled, but the “results are not terribly illuminating.”

One learns that blacks are not especially wanted in Britain, that the equality they enjoy in France is but skin-deep and that after all the best place for the black man is America! One learns also that amongst the blacks there is violent inter-tribal feeling. The high-toned mulattoes of Martinique are scornful of associating with the Senegalese on the ground that they are savages; the Senegalese stand aghast at the impudent assumptions of these descendents of slave ancestors. The Arabs of North Africa despise the blacks of the Madagascar archipelago. (“Negro Renaissance” 15)

Though Banjo contained no revelations, Walrond recommended the novel. He felt it “must be rather bleak and sad” for McKay to realize the conflicts troubling a diaspora that he wished to envision in harmonious community. The fact that Banjo came “from the pen of a man hipped on the universalization of the Negroes” made the challenges to community more poignant. This, “if for no other reason, ought to commend his book” (15). An odd concession, but it is worth noting that Banjo was until recently consigned to the dustbin of literary history, and the terms in which Walrond redeemed it prefigure those articulated by black Atlantic scholars, for whom Banjo indexes in form and content the tensions attending the diaspora.61

The journal in which his review appeared, The Clarion, was an “Independent Socialist Review” whose editorial board included Winifred Holtby, a friend of Robeson and Cullen. Holtby took a keen interest in colonial independence, and when Walrond moved to London in the mid-1930s he would attend her salons. The Clarion was one of the few places his work appeared during his time in France. He reviewed books by Cullen and Paul Morand, and Eslanda Robeson’s biography of her husband. But he did not place much work and lost touch with New Yorkers, including the Guggenheim Foundation, whose support ended in March 1930.62 Efforts were made to burnish his status in France as “un écrivain noir de grande classe.”63 Mathilde Camhi was engaged to translate Tropic Death and may have served as his literary agent.64 But the only translations to see print were a short story, “Sur Les Chantiers du Panama,” and a sensational essay, “Harlem,” both of which were published in Lectures du Soir in Brussels, which also ran an interview. “Chantiers” translates roughly as barracks, and the story dramatizes a conflict between a Spanish merchant who runs a grocery in a small village in the Canal Zone and the West Indian residents. It reappeared later as “Inciting to Riot” in London’s Evening Standard.

“Harlem” was a paradoxical piece of long-form reportage, pandering at times to a prurient French interest in “the Negro,” subverting it at others. With the casual address of a tour guide, Walrond described Harlem as “the African epicenter of the New World, the black capital of the universe,” beginning with a flaneur’s stroll at the corner of 135th Street and Lenox Avenue. A long line of people “wearing loud colors and Sunday finery” assembled at the Lincoln Theater, where “maids, valets, porters, and elevator boys are free to seek their pleasure.”65 Pleasure is the essay’s theme, and Walrond insisted that their laughter was distinctive—“that unique Negro laugh, like the cackling of a barnyard gone berserk—a sound that must be heard to understand the Negro soul.” This characterization sounds essentialist, but Walrond contended that the laughter was a mask. “Beneath the brassy insolence of their humor lies an intense mockery. There is a deep skepticism of the hypocrisy and absurd pretentiousness of mankind, and an understanding that life must be taken lightly.” If the laugh expressed “the Negro soul” it should not be mistaken for unbridled mirth, he suggested, for it was complicated and hard-won. This tension between the language of essentialism and materialism characterizes the article. As in New York, Walrond waded into the murky waters of stereotypes but stirred the pot. “Harlem” is a richly textured account, from the shoeshine stand and barbershop to the cabaret and Striver’s Row. It exhibits narrative flair, as Walrond identifies Harlem’s “most curious and whimsical incongruities.” We learn of the traffic in stolen goods, orchestrated by an entrepreneur whose café was a front for illicit enterprises. However, “Harlem” is a perplexing document, interleaving ribald accounts of theft, prostitution, and vice with sober sociology.

In America, blacks are the last hired and first fired; they occupy the bottom rung of the country’s economic ladder. They pay higher rent than whites for comparable lodgings, and so, naturally, in an effort to build a comfortable life and acquire the same material possessions as white people, blacks often fall prey to installment buying. The American Way of “one dollar down, a dollar a week,” traps them into buying all sorts of things at exorbitant prices.

Refusing to resolve the tension pervading the essay, Walrond ends with a question: “Harlem, African epicenter, black capital of the universe! Do your tumultuous streets contain more immorality than the city of luxury that surrounds you?” Readers led into Harlem’s underworld are thus cautioned against passing invidious judgment on its residents. “Harlem” was an attempt to exploit la tumulte noir and to query its terms. Its double voice was a symptom of Walrond’s own predicament as his Guggenheim support ended: He could not conceal what he knew about the material conditions in which Harlemites conducted their lives, but he also needed to sell stories.

To this end, Walrond was introduced to Lectures du Soir readers in a chatty interview conducted “under the crude light of electric lamps” at Café la Coupole. Jacques Lebar called him “one of the most representative and colorful contributors to Negro literature.” They discussed French literature, Walrond expressing his high regard for Flaubert and Blaise Cendrars, and Lebar asked about U.S. and French race relations. “An important question,” replied Walrond, “especially in the United States, where the persecution of Negroes shows no tendency to subside.” The Great Depression was “exasperating Negroes, who are accused of taking work from whites.” He diagnosed in “American Negroes a veritable psychological duality. On one hand, racial sentiment remains intact; on the other hand, there is a veneer of superficial Americanism.” Things were different in France, he maintained, as “Negroes in your country assimilate more easily. Or we could say that they are French Negroes, while those in the United States are Negro Americans and claim to remain thus.” The distinction he drew is complicated by translation; the interview was likely conducted in English, and Lebar uses the word nègre rather than noir in both its adjective and noun forms. But the assertion is clear—in neither country is the tension between race and nation resolved but the claims of each operate differently. Asked how prejudice could be combated, Walrond was circumspect. “Despite appearances a progressive mixing of the races exists and is growing in the United States, which will lead to a certain easing, even if it takes many years.” In fact, Walrond said he was writing a novel about an African American family, their “relation to life in the United States, their reactions, their rebellions.” He described his concerns in avowedly racial terms. “I have to tell you that white life does not much interest me. My work and my raison d’être are to depict my race’s existence, its history, its suffering, its aspirations, and its rebellions. There is a rich source of emotion and pain there. It is there that I draw the elements of my work, and it is in the service of the black race that I devote my activity as a writer.”

His resolute tone and nobility of sentiment concealed the precariousness of his circumstances. These publications were really too little too late. By the time the interview ran, Walrond had left Paris, fallen into poverty, and suffered an ignominious setback when Horace Liveright broke the contract for The Big Ditch. It is a story that would be lost to posterity except that the person in whom he confided, a talented music instructor in Baltimore, would later marry W. E. B. Du Bois, ensuring the archival preservation of his correspondence. Examining Walrond’s relationship with Shirley Graham not only helps to clarify the mysterious disappearance of The Big Ditch and document a previously unknown period of Walrond’s career, it underscores the methodological challenge of black transnational history. The survival of these artifacts suggests, in its status as an accident, how much else has been lost or muted in the archive.

“THE ONLY REAL LINK I HAVE GOT”: SHIRLEY GRAHAM AND THE DEMISE OF THE BIG DITCH

Shirley Graham and Eric Walrond may have met before the summer of 1930, when she studied at the Sorbonne, but they came to know each other in Paris. A Howard University graduate, Graham had a busy career teaching, directing the Morgan State College music program, and caring for two sons from a marriage that ended in divorce. She took summer classes in the late 1920s at Columbia, where mutual friends may have introduced her to Walrond.66 He was among the first to greet her upon her arrival in Paris. She had a week to get situated, so she strolled the Luxembourg Gardens, imagining the royalty whose steps she traced, gazed from the balcony of her Rue des Écoles hotel at the towers of Notre Dame, and when the opportunity arose she boarded a plane to London to see Paul Robeson play Othello and attend a reopening ceremony for Saint Paul’s Cathedral.67 Unlike a lot of people who “boasted about how well they knew” him, said Graham, Walrond “really did know Paul Robeson,” and gave her a letter of introduction.68 Graham was struck by how little Robeson spoke of himself, since “practically everybody else talked about no one” but him.69 Within a few weeks she wrote an article about him that Walrond submitted on her behalf to Opportunity.

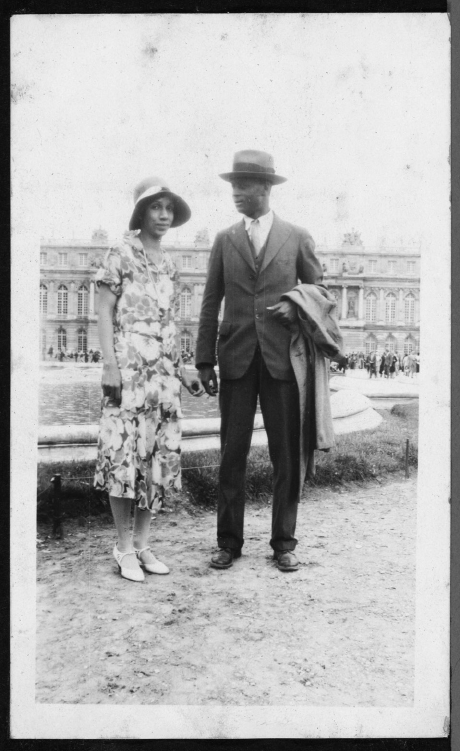

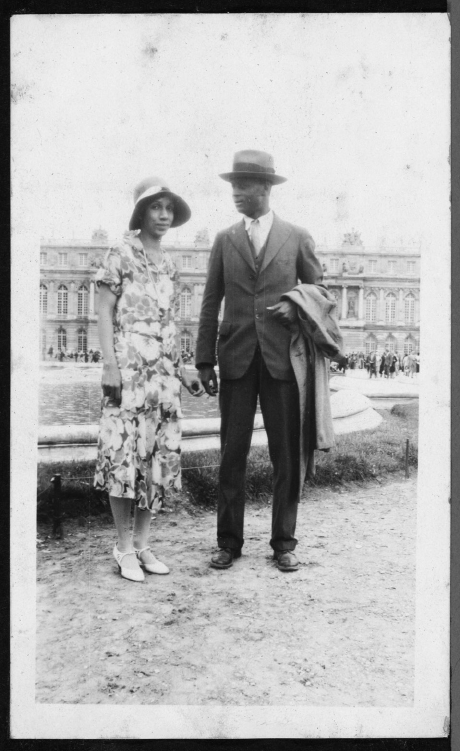

Graham indulged in the legendary charms of Paris nightlife, which offered a great deal to the music enthusiast, but she felt lonely. “I wish for the hand of a dear friend to clasp as I walk these streets,” she wrote to friends in her hometown of Portland, Oregon. She was taken with Walrond’s looks, as “handsome as a Greek god, done in ebony,” and with his talent: “Eric could write!” Their activity in Paris may be inferred from the subsequent correspondence, and while it does not confirm a romance, it does not preclude one. Their friendship was intimate and genuine. “Everyone came to Paris that summer,” she recalled, and Walrond “introduced her to the gang.”70 He implored her to set aside her “phonetics and harmonies and whatever else you’re putting your eyes out with,” and spend time with him, from sidewalk café tables, to the Hotel de la Sorbonne, where Graham borrowed his typewriter to meet a deadline, to the Palace of Versailles, on whose spectacular grounds two black and white photographs document their visit. Graham appears smartly dressed, her floral print dress a fanciful contrast to Walrond’s dark suit and bowler. He appears distracted, glancing past her while she smiles demurely, her pumps tilting her slender frame in his direction. Their hands seem to touch, but closer inspection reveals that he holds a cigarette.

7.2 Photograph of Shirley Graham Du Bois and Eric Walrond, Paris, 1930, photographer unknown.

Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

Graham made sacrifices for Walrond during her stay, or so thought her contrite correspondent a few months later. “I am glad to know that you are well and materially content” in Baltimore, Walrond wrote, “You do deserve some snug bourgeois comforts after the way you roughed it—and all on account of me—in Paris.” Walrond took Graham into his confidence in Paris, which he later consolidated in his letters, calling her “the one person alive who really knows me inside and out.”71 Whatever romantic element their relationship may have had, their correspondence suggests an intellectual companionship—two gifted, black expatriates whose marriages had ended badly, thrown together in lively Montparnasse. Although Graham is remembered as Du Bois’s wife, she was prodigiously talented, the first African American woman to compose an opera for a major professional organization, the author of plays and scores for the Works Progress Administration, and a prolific writer of biographies for young readers. An energetic political activist, she joined the Communist Party and advised Kwame Nkrumah, president of independent Ghana, where she and Du Bois moved in 1961. Her letters to Walrond were not preserved, but his make clear that he relied on Graham for affirmation, a sympathetic ear, and an encouraging word.

Graham returned to Baltimore in September 1930, and Walrond moved to the Riviera.72 It was unglamorous, a fishing village near Toulon called Bandol. His reasons for moving are unclear, but straitened finances were likely a factor. The economic crisis had reached France, unemployment rose, and the dollar accelerated its fall from the empyrean heights that sustained American visits in the 1920s. Walrond may also have needed a break from the Paris expat scene: “Another boatload and Saint Michel might be mistaken for Seventh Avenue,” he groused.73 It was not uncommon for the Montparnasse crowd to flee to the Mediterranean, and Nancy Cunard or William Seabrook were probably responsible for suggesting Bandol. These two eccentrics despised each other, but Walrond knew them in Paris and both had houses nearby. Cunard, who was planning an anthology on “the Negro,” was staying near Nice at the time Walrond left Paris, and they saw each other socially. Her partner, Henry Crowder, an African American musician whom Walrond likely knew from New York, stayed with Walrond in Bandol for ten days.74

7.3 Photograph of Eric Walrond, Toulon, France, c. 1930, photographer unknown.

Atlanta University Photographs, Robert W. Woodruff Library of the Atlanta University Center.

Seabrook, a novelist who supported Walrond’s Guggenheim application, spent the late 1920s drinking himself nearly to death in Paris before repairing to Toulon to continue his bender. He hosted Walrond on at least one occasion and probably more.75 After committing himself to a mental hospital in 1933, he reflected on his alcoholism, and one wonders at the extent of Walrond’s participation: “For nearly two years I had been drinking a quart to a quart and a half of whiskey, brandy, gin or Pernod daily. This had been in France, where liquor is good, plentiful, and not expensive.”76 Now “at the peak of his fame,” Seabrook received a $30,000 advance to serialize his new book, a lurid tale of human sacrifice in Africa.77 But he wrote almost nothing amid the telegrams, visits, and invitations to go tuna fishing, hunt wild boar, gamble at Cannes, and watch “the latest pornographic movies in the red-light district at Marseilles.”78 No account of Walrond’s contact with Seabrook survives, but Walrond’s intimacy with Cunard raised the eyebrows of her partner. “Nancy seemed very much interested in Eric,” said Crowder, “He went to her house to dine but without my accompanying him.”79 Years later, Cunard would assist in Walrond’s discharge from the hospital that treated him for depression.

Soon after Shirley Graham returned home and Walrond moved to Bandol he began writing her, addressing her as “Shirley Old Scout” and gossiping about Paris acquaintances. Walrond relied on her as a professional resource, promising to return the favor. His first letter asked her to send the Guggenheim Foundation annual report and “stray copies” of The Crisis, Opportunity, The Baltimore Afro-American, The Nation, or The New Republic. “I don’t want much, do I?” he joked, “Don’t forget this is a service which I should like to make reciprocal—if there is anything over here that you would like to get and it is in my power to get it for you don’t hesitate to command me.”80 He came to rely on her financially, and she sent between ten and forty dollars on several occasions as his requests grew more plaintive. Graham was not wealthy—until 1928 she made just $35 per month as a music librarian at Howard University, and thereafter her salary as director of Morgan College’s music department was hardly lavish—but she always had something to send him.81

At first he was reluctant to ask for money, promising to pay her back soon. During the winter of 1930, however, his tone changed to desperation and his mental health suffered as his wallet thinned and his hopes of publishing The Big Ditch faltered. He thanked her “multitudinously” for cabling funds, a “life-saver” without which he could not have paid the pension bill. “I can’t begin to describe the ordeal I would have had to undergo,” he said.

Well, I’m out of that hole temporarily at least, but taking colour from optimistic you, I’m going to keep my faith sturdy and won’t cross a bridge before I get to it—even if it is in sight! Your letter and cable have given me courage to stand firm. In spite of economic troubles and because of my isolated surroundings, I’m pounding away—steadily and without interruption. If I only had the assurance of a temporary subsidy while I labored on, I’m sure you’d have some reason to feel your interest in me were not without some justification. Let’s see if we can’t put that idea over the top!

If Walrond left Paris to find an inexpensive writer’s retreat, he instead found loneliness and poverty. “It is a torture for me to write letters,” he said. “But since the ocean separates us it shall henceforth be a pleasure. I’m anxious to hear all the news surrounding you; to get niggerati gossip, newspapers, etc. Unfortunately nothing of any outside consequence happens in Bandol; I’m the only noir in the village.” Friends were unsure of his whereabouts.82

Exile from the black community was a paradoxical strategy for someone whose “work and raison d’être are to depict my race.” The careers of other black writers caution against passing judgment, but in Walrond’s case the strategy proved harmful, both here and again in the 1940s, when he lived in rural England. One letter to Graham contained the poignant admission, “You are the one person alive who really knows me inside and out. There may be something prophetic after all in our meeting.”83 He moved to a cheap hotel near the bay where the fishing boats moored and palm trees blew in the wind as they had in the Colón of his youth. “Since I’ve been here I haven’t been able to go anywhere, or see anybody of the Paris gang or anyone remotely connected,” he wrote after the new year, 1931. “Dear Shirley, write and dissipate the desert island feeling I have got all over me!”84

At such a distance, transatlantic communication eroded Walrond’s connection with New York, and problems arose with his publisher. He confessed “financial worries” that left him “hanging on by the skin of my teeth” and feeling “bluer than I’ve been since before you left Paris.”

My position seems incapable of alleviation. To live down to the lowest margin I need about a thousand francs a month—roughly $40. This amount for the next three or four months I’d give my right arm to get. I can’t concentrate or work on account of the beastly way things just drag along without a silver break to the clouds. I don’t know when my book is coming out but you may rest content that the responsibility for that is now in the hands of the publishers.

Walrond sensed that all was not well, accusing Liveright of “heartlessness and lackadaisical efforts in regard to the book.” Nevertheless, he professed an “abiding faith” that the book “will bring me a lot of undisputed and well-minted prestige.” So firm was this conviction that “in spite of sleeplessness and the usual worries” he determined to write a sequel, a history of the United States in Panama. Research fueled his confidence. “The material I have got to put into the new book will appeal to an even wider audience. It will be a gigantic undertaking though and will easily exceed ‘The Big Ditch’ in length, and that’s a 100,000 word book.” He swore Graham to secrecy: “All of this I relate to you in the utmost confidence as it never pays to let the world know what you are doing until it is actually done,” a bitter lesson of the perpetual deferral of The Big Ditch.

Enlisting Graham, he appealed to her sense of probity. He felt “morally obligated to execute” the new book because the Guggenheim Foundation funded it. Although he had dedicated himself in Panama to “digging up data,” much was left undone.

There are some items I have yet to look up and here, young lady, is where you come in. I don’t know how on Lord’s earth it’s going to be done, but I appeal to you with all the earnestness of which I’m possessed. (If you ever get me out of this fix I’ll about owe you my life!) Is there anybody you know in Washington or N.Y. who has some means of leisure, a kindly heart and a philanthropic spirit whom you can persuade to spend a few hours a day either in the Congressional library or the 42nd St. library in N.Y. copying out data which I shall indicate from old magazines and newspapers and the U.S. Gov’t documents? I grant you this is no easy task but with your influence and get up why I believe anything can be done! Were I in America I’d do the job myself or if I had money I’d employ some professional researcher to do it. But as I’m not in America and have no money I’ve got to exhaust every friendly possibility at my command even though the request may seem to you presumptuous and unreasonable.

However “presumptuous and unreasonable,” his desperation led him to impose on any sympathetic soul. Marvel Jackson had spoken well of him, Graham reported, and although she was now married and they had no contact, Walrond asked Graham to press her into service.85

He also risked presumption because he felt he could offer Graham something in return, professional advice. As a recipient of a coveted fellowship, Walrond’s insight into the Guggenheim process was valuable currency, and Graham sought guidance as she prepared funding applications. Her proposal involved “the tracing of African influence in the musical expression of Europe” and “the African ancestry of American Negro folk music.” Walrond assured her of the project’s originality: “You’ll do much to establish the universality of the Negro genius in general and to modify and even revolutionize the prevailing conception of the comparative merits of African and European music.”86 Graham solicited references from prominent figures, but when she missed the fellowship Walrond reproached her for “cramming your list of sponsors with niggers or negro uplift workers.” He believed endorsements from avowed friends of the race invited suspicion. Suggesting she reapply, he advised her to “look for disinterested sponsors without personal or group axes to grind—your subject is sufficiently scientific in character to merit the endorsement of the best scholars and musicians. And don’t let up working on your plan—revise and clarify it, and don’t drag in Ras Tafari if you can help it.”87 He was concerned, in short, that she not appear too race-conscious.

An uncharitable response to Graham’s rejection, but he was not feeling magnanimous. He had subsisted for months on little or no income. Months of silence from Liveright had dimmed his hopes. “I don’t really despair ultimately of the outcome of my relations with them; only they are so darned slow in giving me a decision and in confiding to me the nature of their plans,” he wrote, “I do still manage to work in spite of them, but I’d work better and with greater confidence if I knew how matters stood.”88 He assured Graham he was “plugging away”; “I have a long new work of fiction half-done and the plans of my Panama sequel laid.”89 Neither the Panama sequel nor the work of fiction, “a novel of Negro life in America,” would see print.90

More than money, Walrond needed Graham’s personal assurance as his distress deepened. When his resolve faltered he lamented, “I can’t concentrate or work on account of the beastly way things just drag along without a silver break to the clouds,” or “I’m working hard as the devil, although a little irksome and impatient at the way things have of dragging on,” or “Nothing seems to terminate as I hope and plan.”91 He tried to sound cheerful, encouraging Graham in her pursuits, “I’m proud of you already Shirley, and I am glad to know you are studying and taking care of yourself and planning to do big things.”92 “I think of you often and marvel at your courage and high ideals. One of these days you are going to arrive in a very big way and then unless I’m all wrong you’ll have a perfectly wonderful ‘up from obscurity’ story to tell.”93 He tried introducing levity by reporting Paris gossip, but he could not conceal his isolation and disappointment. He missed Graham’s comforting presence.

I think often of you and of your incredible kindness to me. Sometimes I, too, feel terribly nostalgic and wish you were around for me to tell my troubles to. But I’m looking forward to this summer when I hope […] affairs may arrange themselves so that we may meet in Paris. As I look back on our days together in the Latin Quarter, I’m sure there was some Grand Design back of our meeting. Do you remember the day you came to the Hotel de la Sorbonne to type your travel sketch to London—every time I think of the result of that encounter, I marvel at the quality of unselfishness and discernment in you which I have found in no one else.94

He became anxious and peevish when she failed to contact him during melancholic stretches. “What has become of you? Ill, ill-disposed, extremely busy? I feel out of touch and worried,” he confessed. “Are you in no mood to write me oftener? Don’t you know that you are the only real link I have got with the world across the Atlantic? I feel sadly neglected and lonesome.”95

Graham agreed to assist with the Panama project, Walrond assuring her that his financial recovery was imminent.

I’m so grateful to you for promising to do what you can on my references. As it stands at present the new book presents but a skeleton of what is to come—I can’t supply the flesh and blood until the research problem is out of the way. You are the only person I have taken into my confidence about it, because it is inadvisable to let cats out of the bag prematurely. My plan is to submit the book as soon as I have got about half of it ready to a publishing house and unless I’m absolutely crazy I believe I’ll be able to raise on it sufficient money to carry me indefinitely.96

The prediction proved overly optimistic, but what is striking is his injunction to confidence and secrecy, a consistent refrain. “You must have an air-tight ‘plan of study,’” he cautioned her early in her fellowship process, “and you mustn’t let too many niggers know what you’re about!”97 He presupposed a field of pitched competition in which leaking one’s plans spelled certain defeat. By late February, with still no word about The Big Ditch, he grew despondent. “You have no idea how I loathe myself and curse the fates at this condition I find myself in,” he told Graham.98

Finally, after spending months in ignorance of his publisher’s plans, Walrond heard from them in early March 1931. Rather than resolving the matter outright, they deferred what he had come to believe was an inevitable letdown.

My publisher [said] there is no question but that I had done an able job in both my actual documentation and in my method of presenting the material in “The Big Ditch,” but that the firm, owing to prevailing conditions in the book market, was unable to come to a decision on it and that I’d have to wait another week or two. It took them nearly five months to write me even as indefinitely as all that, meanwhile I tweedle my thumbs and bite my nails awaiting action. So you see the sort of cochons I have to deal with. They haven’t the decency to come out openly and say they can’t or won’t publish my book but they keep it months and months without letting me know what they are going to do.

As a result, he said, “I’m still in doldrums. […] I don’t wish to be an eternal nuisance but the breaks are a long time coming my way.”99 He asked Graham for the largest sum yet, one thousand francs, “and I’m asking you if there is any way in the world for you to cable it to me as soon as you receive this letter.” Although he had completed only a draft of his “novel of Negro life in America,” he felt “sure as soon as I’ve got it in the shape I desire I’ll get a very substantial advance on it.” With this advance and the publication of his Panama books, he planned to “make adequate liquidation to you for all the money you have loaned me.” He sought to end his exile, “to return to Paris and put the finishing touches to my novel.”

Before Graham had the chance to respond, the final blow fell upon The Big Ditch, and it was even worse than expected. Boni & Liveright had broken the contract and dropped the book. Not because it was poorly executed but because the Depression wrought havoc on the industry, and Liveright, already leveraged beyond recovery, was hedging. If that was not bad enough, he had contrived to prevent Walrond from shopping the manuscript. Walrond’s letter to Graham is worth quoting at length as it is the only extant account of the book’s fate.

The “cost of manufacturing and exploitation is too high” they say and they don’t believe there’d be enough returns to warrant the risk. I’m assured by the chief literary editor of the firm that “this is not an easy decision to arrive at because the scholarship shown in your work, your documentation in particular, and your skillful way of interpreting the story result in your having turned out an excellent piece of history.” But now comes the rub. Liveright himself is afraid to risk publishing the book, and is willing to let me submit it to somebody else but before I’m permitted to do that I must agree to return to him half the money he advanced me on it. In other words, something in the neighborhood of $500. Can you beat that for calamity? I have written him refusing to abide by such [a] tyrannical stipulation. How in God’s name can he reasonably refuse to publish the work and then expect to profit by its publication? In a pinch I suppose I shall have to resort to a lawyer and see what legality there is in Liveright’s terms. If he’d only free this book I’m sure somebody else would take it and pay down an acceptance a minimum of $500. If I agreed to pay Liveright $500 and did succeed in getting another publisher where would I stand? I have executed my obligation to him; if he decides for his own reasons to reject the book it’s no fault of mine. He ought to release the mss. free of all claims and I have written him to that effect.

In one way despite the blackness of the immediate outlook, I’m better off. Liveright has broken his contract with me and therefore all our engagements are off. The suspense is over and though I have the spectre of a $500 rebate hanging over me, I have hopes of connecting with a real publishing house that’ll appreciate the sound value and permanent nature of the work I’m engaged on. Only there is the eternal problem of the interim—this business of carrying on until I bring matters to a head. In this connection you’re the only pal I’ve got in the world. Once you said you trusted me even if you didn’t always understand me. Remember? Shirley, I want you to trust me now more than you’ve ever trusted anyone before. To you and you alone I’m laying bare matters as they stand. I figure it’ll take at most and also at least two months to bring Liveright to terms—to release my mss free of claims which would automatically give me the right to send it elsewhere. I estimate it’ll take another month before I can get action on it. But I firmly believe it won’t take much longer. And as I have told you time and time again I believe in the virtues—historical, literary, and social—of “The Big Ditch.” I didn’t need my publisher’s opinion to confirm my faith in it. I have been conscious of its merits all along—not because I’m conceited for you know I’m not, but because I have laboured on it according to a set plan of perfection and because I have had nothing else but that book in my mind-motions for upward of three years. I wrote you nearly three weeks ago asking you to help me on a $40 proposition. I have heard no word from you so far but hope while this letter is on the way I’ll do so. I have had to put up part of my personal belongings as security against a bill at the pension where I formerly stayed. In the meantime I have taken a room separately and take my meals when I can in a public restaurant. It’s a terribly discouraging state to be in.

Now that you’ve got your Guggenheim application let’s see if we can’t work on my problem a little bit. Shirley I promise you this shall be no losing proposition as far as you are concerned. While I negotiate with my publisher for an “unencumbered rejection” I want to return to my novel of which I have written in my last letter. In the meantime I can’t carry on without funds; my morale is at a nadir and there you are. You’re the only real pal I’ve got and you understand the situation thoroughly. It’d be terrible if I had to throw up the sponge just for the sake of a few months’ expenses. Write me c/o Guaranty Trust and remember I’m praying that matters will arrange themselves we’ll soon be able to see each other in Paris. Good luck and much love. Affectionately, Eric

Driven to despair by Liveright’s extortionate terms, Walrond put his “pal” in an unenviable position. As the only person in whom he confided, Graham was tasked with forestalling his spiral into depression and starvation—a rotten thing to require of a thirty-five-year-old single mother who was in the process of moving from Baltimore to pursue advanced studies at Oberlin College, where she worked in a laundry to make ends meet.100

Walrond’s final letter to Graham suggests that she complied, sending an undisclosed sum. He was relieved “to feel, despite the vicissitudes of the past two or three months, I’ve got a friend back there in America who hasn’t forgotten me or the terrific fight I’m putting up.”101 Nevertheless, “In regards to my situation, I’m sure if I tried I couldn’t exaggerate its gravity. At the moment I’m between two minds: whether to jump in the Mediterranean or sit quietly and expire. There seems precious little else to do.” One could read this as gallows humor were it not for similar declarations during other depressive episodes. He could not produce the $500 Liveright demanded for the “unencumbered rejection,” and he seems to have been too ashamed to ask anyone but Graham for assistance. Walrond would eventually see his way clear to contacting Moe, but not amidst his present humiliation.

I’ve sent the correspondence between me and Liveright to an attorney in America to get his advice on what procedure to follow. In the meantime I’m carrying on a verbal duel with Liveright trying to get him to say definitely whether he will or will not release the mss free of all claims. He hasn’t committed himself so far. I secretly believe the old Jew is playing for this so that he’ll starve me into a surrender. I will probably have to give in in the end but at the moment I’m as uncompromising as nails and do not hesitate to call a spade a spade. I’m not in this damned country for my health.102

In fact, Graham had suggested an alternative to jumping in the Mediterranean or sitting quietly and expiring: return to New York. “You are right about my needing to return to America. I’m homesick and lonely as hell,” he admitted, “If I could get back to New York I could arrange a showdown with my publishers, sell my book to a decent firm and get enough advance money to pay off my debts and go ahead with the plans I’ve made for a Panama follow-up. The only damned question is how on earth am I going to get to America?”

HOME TO HARLEM, WITH A SHRUG

The summer of 1931 is a blank; no evidence survives of Walrond’s activity. Edna Worthley Underwood, Walrond’s sometime agent, said he was hospitalized “for a long time” in the American Hospital in Paris, and given his plummeting finances and mental health in 1931 and the absence of any prior reference to hospitalization, it may have been that summer.103 Perhaps Shirley Graham helped him scrape together the fare to New York, where he arrived on September 5, three years after having left. The Amsterdam News interviewed him, published his photo, and called him a “changed man.” Just how changed they could not know; Walrond played the interview close to the vest. He revealed none of his travails and pledged to return to France within two months. What he made clear was that he did not relish the occasion. “Eric Walrond, Back in City, Feels No Homecoming Thrill,” read the headline. The reporter struggled to identify the ineffable something that distinguished the author from his younger self.

Outwardly he is much the same person as the young short story writer whose volume of sketches on Caribbean life, “Tropic Death,” was hailed by many critics as the flower of a new literary movement. But inwardly there is a difference. And so, when he returned to New York [on] Saturday […] he experienced no thrill of homecoming.

Walrond conceded that he was “glad to see old faces again and to have the opportunity to talk with friends,” but he shrugged his shoulders at the suggestion that it was nice to be “home.” “[T]here’s no particular thrill in being here again. Somehow, I feel different. There has been an inward change. Only urgent business brought me back to this country.” Declining to elaborate, he extolled the virtues of France, an account jarringly at odds with his actual experience.

The south of France is the ideal place for the artist and writer. In the solitude and quiet of that region one gets a perspective on the ultimate. He can see the intrinsic value of the thing he is doing. I wish more of the young Negro writers could do their work in that country. None of the difficulties and interruptions which infest Harlem are present there.

It was a public face to put on things, a vision of what could have been.104

As the article noted, Walrond was staying with his parents in Brooklyn. At a private home, he gave the only public presentation of his brief stay, an address to “The Students’ Literary and Debating League.”105 He obtained an “unencumbered rejection” of The Big Ditch from Liveright, perhaps through the intervention of Moe, who within two weeks was shopping the manuscript on behalf of his beleaguered ex-fellow. Moe approached the Century Company, who acknowledged the inquiry, but that was all.106 Walrond tried to remain optimistic. “As you may have seen in the papers, I’m back in little old New York,” he wrote Graham in Ohio, “Are there any chances of seeing you before long? I don’t know how long I shall be back in the city, having planned to return to France in case everything goes well with me.”107

Walrond looked up his old flame, Marvel Jackson, who had since married Cecil Cooke, discovering she was in the hospital recovering from surgery. Years later she told an interviewer that Walrond mistakenly believed she and Cooke had separated, leading him to profess his love. Someone told her Countée Cullen had admonished Walrond while they were in France for not having married her when he had the chance. His words had sunk in, she claimed, by late 1931, when “I was in my hospital bed, and in walks Eric. I almost fell out of the bed. That was during a period when Cecil was in the south, finishing out a contract, and I was up here. He thought that we were separated, and he said, ‘I really came back because I made a mistake.’”108

Wallace Thurman wrote an essay around this time in which he called Walrond “an unknown quantity” among Negro authors. An apt title for one who had acquired such esteem then receded into virtual silence. Thurman hoped Walrond would fulfill his immense potential.

None is more ambitious than he, none more possessed of keener observation, poetic insight or intelligence. There is no place in his consciousness for sentimentality, hypocrisy or clichés. His prose demonstrates his struggles to escape from conventionalities and become an individual talent. But so far this struggle has not been crowned with any appreciable success. The will to power is there, etched in shadows beneath every word he writes, but it has not yet become completely tangible, visibly effective. […] He knows what he wants to say, and how he wants to say it, but the thing remains partially articulated. Somewhere there is an obstruction and though the umbilical cord makes frequent contacts, it never achieves a complete connection. Thus he remains an unknown quantity, with his power and beauty being sensed rather than experienced. It is for this reason that his next volume is eagerly awaited. Will he or will he not cross the Rubicon? It is to be hoped that he will, for he is truly too talented, too sincere an individual and artist to die aborning.109

When he expressed hope that Walrond would “cross the Rubicon,” Thurman implied two kinds of success: not only that his next book would “achieve a complete connection” between intentions and effects so that “his power and beauty” might be “experienced,” but also that it would bring him recognition.