As they unpacked their bags, hawked their manuscripts around the little magazines of the capital, went on the stump agitating against injustices in far-off islands, they were improvising new lives for themselves, creating new possibilities for those whom they encountered, and decolonising the world about them.

BILL SCHWARZ, WEST INDIAN INTELLECTUALS IN BRITAIN (2004)

hat happened to Eric Walrond? The question had “been asked numerous times over the past several months by persons who remember the promising author,” reported the Baltimore Afro-American in 1935, “No one seems able to answer except that Mr. Walrond left about two years ago for Mediterranean points, and has been gone ever since.”1 The “unknown quantity,” as Wallace Thurman called him, had become still more reclusive. He had granted just one interview during his brief visit to New York, terse and guarded. “Rumors reached [Charles] Johnson from Europe that Walrond had squandered the [fellowship] stipends and written nothing.”2 Even his mother lost track of him, unable to answer the Guggenheim Foundation’s inquiries into his whereabouts. Gregarious by nature, Walrond withdrew and became “very successful at dodging people he didn’t want to know or that he didn’t want to talk with or meet.”3 On moving to London in 1931, he rented a room near the Crystal Palace, a suburb near Brixton. One of his fellow lodgers, an Indian student, struck him as a ridiculous type of colonial subject, performing Englishness, “swallowing hook, line and sinker all the Pukka Sahib nonsense of the British Raj” (“On England” 47). But a subtle shift was under way in London against this mentality. Still relatively small in number, emigrants from the colonies were finding common cause, organizing, and promoting independence. They also sought to end racial discrimination in Britain, the “colour bar.” Most of the newcomers were students, seamen, and laborers, but by the 1930s professionals, artists, and intellectuals began swelling the ranks. Their collective activity and energetic publication program helped bring the empire to its knees and pave the way for future generations calling themselves black Britons. The reclusive Walrond would write his way into this community.

hat happened to Eric Walrond? The question had “been asked numerous times over the past several months by persons who remember the promising author,” reported the Baltimore Afro-American in 1935, “No one seems able to answer except that Mr. Walrond left about two years ago for Mediterranean points, and has been gone ever since.”1 The “unknown quantity,” as Wallace Thurman called him, had become still more reclusive. He had granted just one interview during his brief visit to New York, terse and guarded. “Rumors reached [Charles] Johnson from Europe that Walrond had squandered the [fellowship] stipends and written nothing.”2 Even his mother lost track of him, unable to answer the Guggenheim Foundation’s inquiries into his whereabouts. Gregarious by nature, Walrond withdrew and became “very successful at dodging people he didn’t want to know or that he didn’t want to talk with or meet.”3 On moving to London in 1931, he rented a room near the Crystal Palace, a suburb near Brixton. One of his fellow lodgers, an Indian student, struck him as a ridiculous type of colonial subject, performing Englishness, “swallowing hook, line and sinker all the Pukka Sahib nonsense of the British Raj” (“On England” 47). But a subtle shift was under way in London against this mentality. Still relatively small in number, emigrants from the colonies were finding common cause, organizing, and promoting independence. They also sought to end racial discrimination in Britain, the “colour bar.” Most of the newcomers were students, seamen, and laborers, but by the 1930s professionals, artists, and intellectuals began swelling the ranks. Their collective activity and energetic publication program helped bring the empire to its knees and pave the way for future generations calling themselves black Britons. The reclusive Walrond would write his way into this community.What he subsisted on in the early 1930s is unclear, but subsistence it must have been because the work he published—sketches and fugitive essays—could not have supported him. He got by, as a reporter for the Afro-American discovered in 1934.

Eric Walrond, one of the better writers, has made London his temporary hunting ground. He has the energy of a dynamo; gets up at seven in the morning; drinks a cup of tea in bed, reads the daily papers, smokes at least five cigarettes and then settles down to work. Writes until noon and then for a hike in Hyde Park, back to his desk at two thirty and writes until six. Drinks gin and chews spearmint gum while typing. Claims that England is Virgin territory for young colored men and women of letters; intends to stop here until the field is properly explored.4

A portrait of English discipline, stimulants and all. But he struggled to place his work. London’s mainstream periodicals, such as The Spectator, The Star, and The Evening Standard, picked up a few stories. His published journalism included two essays translated into Spanish, an article in London’s Sunday Referee, and another—a brilliant sketch entitled “White Man, What Now?”—that The Spectator carried and The Gleaner reprinted in Jamaica. But without regular income, he foundered. Help came in the form of Amy Ashwood Garvey and her Trinidadian companion Sam Manning, who arrived from New York and opened a Caribbean nightclub near the British Museum. When Manning offered him a job as the publicity manager for his “negro musical revue” planning a UK tour, Walrond took it. That such a fate befell “one of the better writers” with “the energy of a dynamo” says as much about London’s difference in the 1930s from 1920s New York as it says about Walrond himself.

The challenge West Indian authors faced in England in the early 1930s was formidable, and Walrond’s difficulty was not unique. Publishing opportunities were few and far between until the 1950s, and periodicals treated West Indian authors, particularly those quarreling with imperialism, with circumspection. Many “had to be convinced on ideological, social, marketing, and sometimes racial grounds before dissenting authors could get their words into the public domain.”5 Peter Blackman, a Barbadian theology student and leader of London’s leftist Negro Welfare League, explained the resistance: “The West Indian author who hopes to succeed as a novelist looks outside the islands for a market,” he wrote in 1948. “In most cases his hopes are pinned on England. But the themes he touches, the questions he raises, cannot greatly interest, can often disquiet and embarrass Englishmen.”6 Despite this reticence, the 1930s generation succeeded in developing a periodical culture that was unprecedented in its anticolonial ambition and international reach. Scholars place a higher value on books than periodicals and rate fiction over journalism, but the fact is that the West Indian novel as we know it had not yet been invented. The real cultural action in 1930s England was in journalism, fostering independence activity and galvanizing Pan-Africanism, a movement that, by the end of World War II, linked Manchester to New York to Lagos to Port of Spain to Johannesburg.7

London was a critical site, as writers arrived during upheaval in the colonies and emerging fascism in Europe. Even George Padmore, the most prolific of these activists, struggled to publish in book form and was most effective in periodicals, both in Britain and its possessions and in the United States, where during World War II he had 575 bylines in the Pittsburgh Courier and Chicago Defender alone.8 To label Walrond “the writer who ran away,” one from whom nothing was heard after 1929, as scholars have done, is to miss his role in this burgeoning periodical culture.9 Walrond’s supposed decline is belied by his contribution to this signal achievement in twentieth-century black letters, and his disappointments are as vital to understanding this achievement as are the triumphs of others.

Whatever similarities obtained between white supremacist practices in England and the United States, a long history of African American political struggle and acculturation conditioned the possibility for the New Negro movement in the United States, while in 1930s England people of African descent were not only fewer in number but also lacked a national narrative authorizing their claims upon the nation. As colonial subjects, they could claim colonial citizenship and even Englishness but could not claim England itself. Walrond began writing about England’s “colour bar” at home and colonialism abroad shortly after his arrival, insisting on their connection. His path to publication in London resembled the one he had pursued in New York. Facing an industry that was indifferent if not dismissive in New York, he published pulp stories and eventually found work with the journal of Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Similarly, his first publications in London were the stuff of penny dreadfuls, when who should appear in late 1934 with plans to rejuvenate the UNIA but Garvey, bearing a job offer. Walrond had just published the stories “Tai Sing” in The Spectator and “Inciting to Riot” in The Evening Standard. Despite their sensationalism, the stories are not without merit or interest. Anticipating by several years the Caribbean “barracks tales” of C. L. R. James, Edgar Mittelholzer, and Victor Reid, they are among the first works of Caribbean fiction published in England.

Set in Panama, both stories dramatize a conflict between West Indian laborers and merchants there to seek their fortunes. They convey an atmosphere of frontier lawlessness and revel in the friction of crosscultural communication. “Tai Sing” is a Chinese shopkeeper straight from central casting. He speaks in demotic dialect (“Me tek,” “Me like,” “You pay Chinaman, else yo’ no can have bag”) and is thoroughly infantilized (“A small boy with a toy gun, or a monkey with a peanut, could hardly have been happier than was Tai Sing with the revolver” [25–26]).10 Tai Sing discharges his weapon twice in the story, murdering West Indians both times. The first is just for the thrill of it; he “wanted, in a sudden impish upsurge, to hit something that could feel,” and that something is a “Negro” pushing a cart “full of smoky blue chunks of stone and clotted earth” (27). The second is a Jamaican itinerant nicknamed ‘Fo ‘Day Morning, whose “bare feet and trouser legs were spattered with the brick-red clay” of the canal cut (25). ‘Fo ‘Day—whose name reflects his routine, rising before daybreak—refuses to pay Tai Sing for minding his valise, and Tai Sing, tired of mouthy West Indians, shoots him with the revolver to end the story.

“Inciting to Riot” stages a similar conflict between West Indians and an immigrant shopkeeper, this one a grocer from Spain. Juan Poveda harbors a deep animus toward the “sacré negroes jamaicanos” because of an assault he suffered while supervising a work crew. Harassment from his customers pushes him over the edge, provoking him to an “avenging passion” (35). “Inciting to Riot” contains wonderful dialect, as when a laborer yells at Poveda, “Is fight yo’ want, fight? Tell me, is fight yo’ want, fight?” (35). “Some people can teef an’ got so much mout’ besides,” says a woman witnessing a neighbor steal from Poveda then defend herself (32). Two elements link this story with “Tai Sing” beyond their plots. One is the shadow presence of the French, who lurk in the background as the Canal Zone’s occupying force. The other is the vulnerability of the West Indian community to violence and the near impunity of the perpetrators. In neither story is the murderer brought to justice; his behavior is merely reprimanded as inflammatory, liable to incite a retaliatory mob. The stories were likely based on folk legends, and although they indulged in the sensationalism and stereotypes of pulp fiction, they incisively depicted the precariousness of West Indian lives in Panama and the tense coexistence of multiethnic communities.

Between “Tai Sing” and “Inciting to Riot,” two of Walrond’s essays were translated into Spanish and published in Madrid, one concerning the Panama Canal construction, the other a somber meditation on Harlem’s decline during the Depression. The Depression had “undermined profoundly the proud notions of self-sufficiency of the ‘black belt’ of New York” (“El Negro”). A remarkable community was ravaged, its residents often the last hired and first fired. For white Americans, Harlem had been little more than a playground, “a great center of extravagant and exotic diversions,” but for African Americans it had deep material and symbolic significance, the attenuation of which was painful to behold. The fragmentation and dispersal Walrond identified with Depression-era Harlem had an unmistakable feel of autobiography: “In these days of misery, hunger, and uncertainty, the Negro cannot go running after empty ideals which don’t satisfy his hunger and can’t even pay his rent.” “The self-sufficiency” of the Harlem “Negro” “was, in reality, no more than a mirage brought about by the quicksand of credit and excessive confidence based on speculation.” He would have said the same of his own career, of his own self-sufficiency, after philanthropic foundations and speculators in the literary market had created for him—the mirage of a career, the quicksand in which he was mired. He could not write his way out of it with the occasional article, not in early-1930s London.

Conditions were terrible among black Britons and showed little sign of improvement until the end of the decade. After demonstrating their love of king and country during World War I, some of the fifteen thousand men in the British West Indian Regiment moved to Great Britain, and they, along with thousands of colonial seamen and laborers, became scapegoats when the Depression struck. Although the worst tensions flared in seaports such as Liverpool and Cardiff, where fifteen hundred “coloured” were unemployed, factory towns such as Manchester were rife with hostility, as was London. “Things were hard for we people,” said one West Indian, “Them days John Bull will shoot you if he see you with him woman. They like their woman pass God self.”11 African, Asian, Caribbean, and Arab seamen were required by law to register with the police as resident aliens and threatened with deportation and imprisonment. Jamaican writer Una Marson “dreaded going out” when she arrived in London in 1933: “People stared at her, men were curious but their gaze insulted her, even small children with short dimpled legs called her ‘Nigger,’ put out their tongues at her. This was her first taste of street racism. She was a black foreigner seen only as strange, nasty, unwanted.”12 The press offered few avenues of redress. The African Progress Union and the West African Student Union (WASU) were established, but vigorous antiracist and anti-imperialist campaigns only gained ground in the mid-1930s: with the arrival of Marson and C. L. R. James; the inception of the League of Coloured Peoples journal, The Keys, in 1933; the arrival the following year of George Padmore and Marcus Garvey; and the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, which quickened anti-imperialist sentiment.

It was thus a blessing that in the summer of 1934 Ashwood and Manning arrived to save Walrond from his writing routine of cigarettes, gin, and spearmint gum, for his prospects were dim. Manning hatched a plan involving Walrond touring the UK with the “first British negro revue.” A great popularizer of calypso, Manning was responsible for seven of the first nine calypso recordings in England. The “negro revue” drew from calypso and a repertoire of numbers from the New York stage. Calling themselves the Harlem Nightbirds, the group “featured singers and musicians from Britain’s old Black communities of Liverpool and Cardiff, supplemented by more recent Caribbean arrivals,” a kind of goodwill tour.13 Manning was a savvy fundraiser, securing the support of wealthy Londoner Clifford Sabey. After opening engagements at Queen’s Theatre, the Nightbirds toured the UK with Walrond as publicity manager in spring 1935, performing at the Blackpool Opera House in Lancashire and in the cities of Birmingham, Manchester, Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Belfast, among others. Walrond executed his task capably, with notices appearing in London, in regional newspapers, and in the Trinidad Guardian, where an article bore the provocative title, “West Indian ‘Night Birds’ in London: All Black and All-British.”14 The Baltimore Afro-American learned of Walrond’s activities and implied that the mighty had fallen. “It is out now: Eric Walrond is touring the continent with a musical revue; from writing for the sophisticated journals as one of the exponents of the ‘new renaissance,’ he is now penning publicity about the travelling vaudeville troupe.”15

As the Harlem Nightbirds made their way from Birmingham to Wigan on the tour’s final leg, Walrond must have been gratified to see his essay, bearing the confrontational title “White Man, What Now?” on newsstands. The Spectator was not radical, and Walrond’s essay is remarkable for its restraint. He employed a double voice that muted its critique of English racism and colonial paternalism. The irony of English prejudice against West Indians, he argued, was that West Indians like himself had always considered themselves English.

As a West Indian Negro, I was reared on the belief that England was the one country where the black man was sure of getting a square deal. A square deal from white folk has always seemed so important to us black folk. Our position in the West Indies, in virtue of the ideas instilled in us by our English education, has been one of extreme self-esteem. We were made to believe that in none of the other colonies were the blacks treated as nicely as we were. We developed an excessive regard for the English. We looked upon them as the most virtuous of the colonizing races. It was to us a source of pride and conceit to be attached to England. We became even a bit truculent about it (279).16

But Englishness exacted a price, he maintained, at home and abroad. “Our love of England and our wholehearted acceptance of English life and customs, at the expense of everything African, blinded us to many things. It has even made us seem a trifle absurd and ridiculous in the eyes of our neighbours” (279). Only in traveling, he said, did West Indians realize the “absurdity of our ostrich-like” stance. In Panama, residents harbored “a strong feeling of antipathy toward British Negroes,” a disdain “engendered by our love of England” and expressed in epithets and “occasional armed incursions” into their communities (280). Conditions in the Dominican Republic were similar, though their “terms of endearment” were cocolo instead of chombo. In Haiti, he found a long-held “grudge” against the English that “loosely extended to Britain’s black wards in the Caribbean” (280). In Harlem, the appearance of community concealed a rift along national lines, as the West Indian “was joked at on street corners, burlesqued on the stage and discriminated against in business and social life. His pride in his British heritage and lack of racial consciousness were contemptuously put down to ‘airs’” (281).

Indelibly marked by their Englishness everywhere else, West Indians were dismayed to be poorly treated in England, where they arrived “in the spirit of chickens coming home to roost.” “We possess the undying certainty that in England we shall be on the equivalent of native soil. Trained to believe ‘there is nothing in race,’ and that there is no difference between ourselves and white folk, we expect to be treated on that basis” (281). In a closing flourish, he raised the issue weighing heavily on black Britons with a marvelous irony: “We do not suspect the existence of a Colour Bar. And so thorough has been our British upbringing that if, in the event, we did find a Colour Bar, we would consider it ‘bad form’ openly to admit its existence” (281). It was an English way to end an essay asserting West Indians’ Englishness, mordantly witty and delicate in suggesting a difference from the strident militancy of American activists.

Reprinted in the Jamaica Gleaner, Walrond’s essay appeared at a critical juncture in British race relations, sharpened by events in the Caribbean and Africa. At home, the League of Coloured Peoples conducted an extensive study of dire conditions in Cardiff’s “coloured” community; and although the circulation of its journal, The Keys, was a modest two thousand, the League’s director, Harold Moody, was the most influential black voice in domestic politics, and the study appeared amid the furor provoked by Italy’s invasion of Abyssinia (Ethiopia). New York’s Amsterdam News reported that Walrond was “returning from London soon with two manuscripts,” but in fact his imagination was captured by the volatile transition England had entered. On occasion he wrote about Harlem, publishing a review of new books by Hughes and Hurston in The Keys and a story in The Star entitled “Harlem Nights.” But by 1935, James’s The Case for West Indian Self-Government, published by Hogarth Press, was the subject of vigorous discussion, as was Padmore’s How Britain Rules Africa.17 Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia provoked Pan-African and antifascist sentiment. Padmore and James joined Amy Ashwood Garvey, Paul Robeson, and Ras Makonnen to form the International African Friends of Abysinnia, soon renamed the International African Service Bureau (IASB), a more radical organization than the League of Coloured Peoples (LCP), led by Moody and Marson. Along with WASU, these organizations were consistently publishing work of high quality, cultivating a periodical culture with an international reach.18

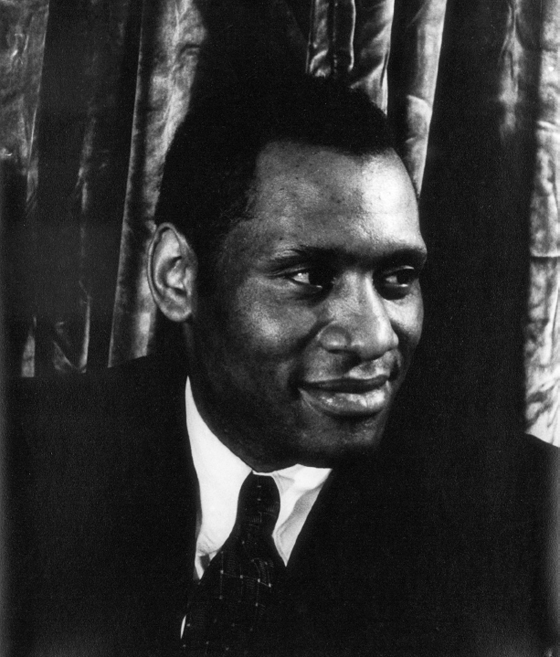

8.1 Photograph of Paul Robeson, 1932, by Carl Van Vechten.

James Weldon Johnson Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. Courtesy of the Van Vechten Trust.

8.2 Photograph of Amy Ashwood Garvey, date and photographer unknown.

Courtesy of the Lionel Yard Collection, Brooklyn, New York.

Walrond felt the Ethiopian invasion was a threshold event. In an article reprinted in The Pittsburgh Courier and The California Eagle, he urged intervention on behalf of the Ethiopians and the rest of “the world’s two hundred million Negroes.” Since one-fourth of these were her own subjects, Great Britain had a special responsibility, he argued. “Walrond points out Ethiopia is a symbol of the destiny of the world’s Negro millions,” reported the Eagle. “The attack on Abyssinia is not a colonial venture; it is a trial to prove whether the most advanced mind and conscience of the white people can remain satisfied by a new relation which will confirm the hideous slavery of the past” (“Writer” A2). Walrond cast Mussolini’s invasion as a threat to British colonial relations. “If given a free hand in Africa he will stand a chance of kindling a violent war between the black and white races, which can only react disastrously on the position of the great Colonial Powers. Two hundred million people cannot forever watch with complacence their destiny torn by bayonets” (“Writer” A2). However, the invasion elicited a tepid response from British officials, even after Haile Selassie, Ethiopia’s emperor, sought refuge and an audience in Whitehall. Walrond was among the growing number whose dashed hopes for a firm rejoinder to the fascists led to disillusionment with the Colonial Office and increased militancy.19

And it was not just black Britons; the movement was multiracial. Among the gatherings Walrond attended were those of Winifred Holtby, a white novelist and friend of Robeson’s. With cohost Vera Brittain, a wealthy pacifist and writer, Holtby invited intellectuals and activists to their Russell Square salon. On one occasion, Walrond joined Holtby’s cousin Daisy Pickering, the writer Odette Keun, and Una Marson of the LCP.20 Marson’s interest in the New Negro movement led her to consult Walrond about his peers in the States and solicit his review of Hughes and Hurston for The Keys, but he did not become a regular contributor. Instead he took a job with Marcus Garvey’s The Black Man, the journal of the revived UNIA in London. The deciding factor seems to have been money—Walrond received a small retainer to work in the office and to contribute his writing—but the affiliation produced some of his best writing in England, seven articles and a story. He was among a handful of writers alert to the political and cultural potentialities of the diaspora, committed to articulating the jarring experience of black Britain in its formation.

THE BLACK MAN

Marcus Garvey tried to put a brave face on a relocation that was really an act of desperation. Although the UNIA remained in operation after Garvey’s deportation in late 1927, the organization was bankrupt and in disarray.21 Adversity never diminished Garvey’s bravado, however, and he announced a ten-year, six-hundred-million-dollar program in 1928 “for the development of the Negro,” established a new UNIA headquarters in Kingston, and ran for public office. But when he criticized “corrupt” judges, he was indicted, imprisoned, and soundly defeated in the election. From Jamaica, he could not control UNIA operations in the United States, where dissent increased, and as early as 1931 he expressed a desire to start afresh in London. Arriving there in 1935, he kept a modest UNIA office in West Kensington and sparred regularly with Hyde Park’s polemicists at Speaker’s Corner.22 It was a far cry from the massive rallies of the early 1920s, and his diminished status likely contributed to his willingness to reach out to Walrond, with whom he had fallen out ten years earlier.

The relocation failed to restore the UNIA to its former glory, nor was The Black Man as important as other periodicals in the movement, but its twenty-four issues fanned the flames of anticolonialism and Pan-Africanism, transforming local initiatives into a broader, concerted campaign. The Black Man printed Garvey’s final addresses—speeches delivered in Canada and the West Indies—including the principles of “The School of African Philosophy.” Despite what Robert Hill calls “the sheer monopoly Garvey exercised over editorial matters,” Walrond’s contributions departed from the UNIA party line as often as not. He embraced historical materialism, a Marxist viewpoint at odds with Garvey’s “increasingly idealistic conservative ideology.”23 Moreover, Walrond recognized the potentiality of black Britain in a way Garvey did not, for Garvey loathed his “competitors” in London and continued to see African Americans as the political vanguard.24 The Black Man made “no direct mention of any of the important political initiatives or essential welfare functions which [London’s] remarkably diverse and talented group of individuals and organizations undertook.”25 Their influence registers in Walrond’s articles, however. He quoted Padmore approvingly, for example, but did not mention Garvey or exhort readers to join the UNIA. What The Black Man provided Walrond, in short, was a platform for a more militant critique of British conduct at home and abroad than mainstream periodicals permitted.

The kid gloves came off immediately in “The Negro in London,” a 1936 essay that dispensed with the restraint he had shown in “White Man, What Now?”

Viewing the “Mother Country” with an adoring eye, the Negro in the British overseas colonies is obviously at the mercy of the rainbow. He sees England through a romantic and illusive veil. What he so affectionately imagines he sees does not always “square” with the facts. This deception, common to the virgin gaze of African and West Indian alike, is partly a case of “distance lends enchantment,” partly a by-product of the black man’s extraordinary loyalty to the Crown. On coming to England the first impression the black man gets is that of utter loneliness. […] The Negro is made to feel as some species of exotic humanity from another planet, and this despite the 50,000,000 negroes in the British Empire (282).26

Walrond was mapping out a contradiction few writers at the time articulated. A generation later, the central trope of an emergent body of literature would be the jarring “moment when the emigrant came face to face with the lived realities of the civilisation in whose name he or she had been educated into adulthood, as distant subjects of the Crown.”27 But in the 1930s, Walrond was among the few with the comparative perspective from which to formulate black Britons’ “discrepant reality” and the temerity to express it.28 Having lived in British colonies, a Latin American country under U.S. occupation, and in New York and Paris, he was uniquely situated to address England’s distinctiveness.

And he did find it distinctive. There is “a peculiar Negro problem” in Britain, he claimed, “despite so little one hears about it.” It was not that treatment was uniformly bad, though in several cities segregation prevailed and “the feeling among whites is one of subtle antagonism” (283). It was that English racial attitudes were inconsistent and inscrutable. Outside London, the “keen competition for jobs” and the observance of a colour bar in employment and housing compelled black Britons to “fall back on the dole or eke out a miserable existence in some shady precarious undertaking” (283). “The problem of the Negro in London,” however, was “much more complex and varied.” In the East End, the high concentration of “discharged seamen from the farthest corners of the Empire” made conditions as desperate as in “the distressed areas of the North of England.” Elsewhere, they were “enmeshed in a maze of bewildering subtleties and paradoxes.” They might be rented a room or denied one, merchants might greet them with warmth or contempt, and students were invited from the colonies to study, while professionals and artisans were unwelcome, so “the educated Negro who is neither a doctor or a lawyer is of necessity a ‘bird of passage,’” and students completing their degrees are “subtly discouraged from settling in England.” In short, “the black man never knows just how the Englishman is going to take him” (284).

The most unnerving paradox was the English pride in their empire and their ignorance about its residents; they “lump them all together, and [are] invariably astonished to find them in command of the English language” (284). It was vexing, he concluded, “that London, the capital of the largest Negro Empire in the world—the cradle of English liberty, justice and fair-play—the city to which Frederick Douglass fled as a fugitive from slavery—should be so extremely inexpert in the matter of interracial relations.” But his prior experience offered some comfort, for “in this respect, […] London may be easily compared with New York twenty years before the big migration which resulted in the establishment of Harlem” (285). His prediction was accurate; twenty years later, George Lamming, Sam Selvon, V. S. Naipaul, Andrew Salkey, and Roger Mais were forging a place for West Indian fiction in England; Una Marson and Henry Swanzy brought Caribbean Voices to BBC Radio; and Claudia Jones, Trinidadian by way of New York, fled McCarthy’s persecution and started the West Indian Gazette. Their work would not have been possible without their 1930s predecessors, who faced a British public that was indifferent if not hostile.

Having participated in the New Negro movement, Walrond could not conceal his impatience with conditions in London. Other West Indian writers were more circumspect, some advising immigrants and visitors to be deferential and know their place. Walrond chafed under this paternalism, recalling the assertiveness of black New York and the freedoms of Paris (“On England” 289).29 He wrote withering critiques of imperialism in The Black Man, calling England’s pretense of democracy a “farce.” He conceded that the monarchy was not absolute, but it excluded voices outside Great Britain.

[T]he Empire is not confined to the British Isles; it sprawls over vast territories halfway round the globe and includes among its citizens millions of black, brown and yellow men, women and children in Africa, India, the Far and Near East and the Caribbean area. But these millions of citizens have no voice in the government of the Empire. There is no one at Whitehall or Westminster to plead their case. (“On England” 291)

The essay pursued the argument to the tremendous labor unrest that had provoked strikes and retaliatory crackdowns throughout the Caribbean.

If as workers they find themselves in conflict with the sugar interests of Jamaica or the oil field owners of Trinidad, there is nothing they can do but submit to the repressive acts of the Colonial Office. They are a crushed, unorganized and completely voiceless mass. Unlike the coloured natives of the French Colonies, who send their own men to represent them in the Chamber of Deputies in Paris, they are utterly at the mercy of a system which even refuses to give them a hearing. Under such conditions can anybody seriously call England a democracy? (“On England” 291)

It was a rebuke the mainstream press would never have printed, an illustration of the critical function London’s black periodicals performed.

Despite his radical affiliations, Walrond was invited to a coronation party in May 1937 for King George VI. Prominent figures from across the empire and luminaries from the United States descended on Aggrey House, a hall the British Colonial Office furnished for colonial students. The attendees included prominent African Americans such as Ralph Bunche and Ethel Waters; Caribbean visitors such as Audrey Jeffers, the first female councilmember in Port of Spain, Trinidad; and African elites such as the Alake of Abeokuta (“paramount chief of Nigeria”). These were respectable guests whose presence the Colonial Office could endorse, but their respectability did not preclude revelry, and they took their cue from Harlem’s latest dance sensation: truckin’.30 Walrond must have enjoyed the scene of the assembled giving truckin’ a disaporic twist. “All night while the King and His men were pitching a ball at Buckingham Palace, the Africans from the motherland and those from the U.S.A. broke it down in Aggrey House. One of the West Indian boys told” California Eagle editor Fay Jackson “that the Chieftains and the high powered barristers put on the dog before the ofays but they can be really human among ‘their own.’”31 The notion that the colonial elite dissembled to impress the British struck Jackson as delightfully subversive, and she relished the irony of the segregated celebrations conducted “while the British were crowing over their One Big Happy Family Empire.” Coronation festivities also furnished an opportunity for Walrond to report on the “colour bar.” Discovering that white women were banned from a coronation reception in Brighton for Indian servicemen, he wrote an article for The Pittsburgh Courier alleging miscegenation anxiety. He cast the episode, which involved an invitation Brighton’s mayor issued to 450 Indian troops, as a tempest in the brittle English teapot of race prejudice (“Ban” 7). The length to which Britons went to prevent socializing between white women and nonwhite men was a subject to which Walrond’s reporting would return.

The Black Man was a platform for the militancy Walrond could not have expressed elsewhere, but his increasingly Marxist views were at odds with Garvey’s conservatism. It is unlikely that he joined the Communist Party, but a number of factors made Marxism compelling. These included the Depression, the Scottsboro trial, in which the Communist Party USA led the defense, and closer to home, the rise of Sir Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists, against which Communists led the opposition.32 The Marxists Walrond knew, such as Padmore, James, Robeson, and Ashwood Garvey, had complicated relationships to Communism, but their opposition to fascism and their class analysis appealed to him.33 Adopting Marxist categories in The Black Man, he cast colonialism as a ruthless competition among advanced capitalist states for labor and markets. This analysis is all the more striking in light of the strenuous anti-Communism of Garvey, who devoted a whole chapter of this period’s “Lessons from the School of African Philosophy” to the perils of Communism. His contempt extended to Robeson, whose films he attacked for misrepresenting the race, and Padmore and the IASB, whom he blamed for the violence attending labor disputes in the Caribbean.34

Walrond’s Marxist turn was sharpened by what he saw as the repellent “class basis of British society.” The figure of the English gentleman provoked his ire, a creature whose vices and invidious social role were concealed by an appearance of gentility. “Any person of gentle birth, any unborn candidate for the playing fields of Eton, any suave, gilt-edged rascal may be a gentleman,” he wrote. “He may be a jewel thief, a blackmailer or one who lives by his wits, and yet be one” (“On England” 290). He launched a searing class critique.

“Gentleman” is nothing but a catch-word; but a catch-word that serves a deadly purpose. It is used to bolster up the social and economic division between the upper and lower classes. It puts a premium on the well-born and serves notice on the under-dog that the line which separates him from his “superiors” is an ineradicable one. […] It has nothing to do with morality in the abstract. No bloke of a Cockney, however decent or upright, may aspire to that lofty estate. Purity of mind or heart is not enough. If he manages by sheer merit to emerge from the ruck and carve out a career for himself […] he is looked upon at best as a curiosity. (“On England” 290)

Social conditions were once again changing Walrond’s analysis and his sense of the relationship between art and politics. “If [the Negro] aspires to rise and move on to a high destiny, and not just be a helpless pawn in the game of Power Politics, he may have to alter his whole outlook on the world he lives in.” Walrond seemed to be exhorting himself as much as his readers: “He cannot afford to be a stick in the mud. He may even have to revise his scale of values. He must be resilient and adaptable, and not be a romantic—out of step with the rhythm of the times” (“Negro Before” 286). It may have suited the New Negro to craft fine literature, he suggested, but times had changed, as had his location.

Employing a Marxist lexicon of value and private property and a model of history propelled by class conflict, Walrond explained the African diaspora as the underside of capitalist expansion. Africa was “the source of intense rivalry among the colonial powers,” he wrote, and the African, whom he figured as a male threatened with emasculation, had struggled for centuries for sovereignty. If the Ethiopian crisis—African swords succumbing to Italian ballistics—was a source of humiliation and outrage, the displaced New World African had fared little better, “sold like cattle in the slave markets,” “wincing under the slave-driver’s lash” for three hundred years. “His lot was no better than oxen and sheep—with which he ranked in the white man’s scale of property values” (“Negro Before” 287). By this account, it was political economy, not prejudice, that determined relations between races. The end of slavery had not ended “Negro” subjugation because the underlying economic system remained intact. “When, after the reading of the Emancipation acts, ‘freedom’ was revealed in all its emptiness, the powers that be contrived by their system of economy to re-enslave the Negro.” The system to which the “Negro” was “yoked” had one objective: “to enrich and confer power upon a small governing class.”

In its thrust the argument was classically Marxist, but in its particulars, drawn from the Caribbean and the United States, it invoked a black proletariat.

The men wielding the whip-lash—the sugar barons and the cotton kings, the factory owners and the absentee landlords […] were not going to let a little thing like abolition thwart them in their desire to perpetuate themselves and their class in power. By exercising a monopoly on capital, they were able to exploit the black man, thrown penniless on a hostile world, just as easily as when he was a chattel slave. (“Negro Before” 288)

His confidence eroded by “years of bodily and mental enslavement,” the “Negro” considered Africanness a source of shame, the mark of an “inferior being—without a past or a future, a heritage or a destiny—ordained by God to occupy the lowest rung of the human ladder.” The tragedy lay in this mystification, compelling “Negroes” to misperceive their collective self-interest. “To escape from the blind alley up which he was being pressed, the black man, instead of opposing the system that oppressed him, set out, curiously, to build his hopes and ideals around it” (“Negro Before” 288).

But a good dialectician identifies forces available for harnessing resistance, and Walrond noted promising conditions amid the “chaos.” “Side by side with his enforced humility, the black man […] has kept the spirit of independence alive. Who knows but that at a time not far distant the war-clouds over Europe may darken into night?” A second “Great War” seemed imminent by 1938, and Walrond envisioned a crisis of the entire architecture of colonial capitalism. “When, and if, that time ever comes (no one doubts but that it will mean the collapse of the capitalist systems in Europe) the white man’s rule over Africa will be at an end” (“Negro Before” 287).35 Given Garvey’s avowed anti-Communism, the appearance of this article in The Black Man suggests either his editorial aloofness or the autonomy Walrond enjoyed. Its subversive thesis could not have been more plainly stated, that “there can be no salvation for the Negro until and unless he takes a firm stand against” capitalism and imperialism. This argument resonated with contemporary expressions of Pan-Africanism such as Padmore’s How Britain Rules Africa, James’s History of Negro Revolt, and Césaire’s Notebook of a Return to My Native Land. It was at odds with Garvey’s hierarchical vision of authority derived from his location in Europe’s capital of finance, handing down “commands from this great city where men move and act in controlling the affairs of the world,” as he enthused.36

On no issue did Garvey prove more woefully out of step with Walrond and other black radicals than the Ethiopian crisis. Initially, he expressed outrage that the world’s powers stood idly by as Mussolini invaded a sovereign African nation. But he became critical of Selassie, blaming the emperor for the defeat of his people, a position that infuriated other Pan-Africanists. He dissociated himself from the Communists, for whom Selassie was a cause célèbre.37 Walrond, by contrast, examined the circumstances of Ethiopia’s collapse and published an investigative report, his longest article in The Black Man. “The End of Ras Nasibu” offered a detailed account of Ethiopian attitudes toward war and errors of military strategy. He conceded that Ethiopians had been naïve and Selassie had made “ill-advised” decisions, but he asserted that the League of Nations abdicated responsibility and that Ethiopia’s defeat left many martyred “in the cause of Abyssinian, and Negro, independence” (15). Even the moderate LCP, mainly concerned with education, social welfare, and bussing children to the salubrious countryside, was radicalized by the Ethiopian crisis, leaving Garvey practically alone “clutching at the chimera of a movement whose historic moment had long since passed.”38

As sabers rattled in preparation for war, Walrond became intrigued by the practices of recruiting and training colonial subjects. He was moved by the bitter recognition that soldiers of color had participated, sometimes on the front lines, in wars against people toward whom they harbored no enmity, often other people of color. These were intricate paradoxes to which he later returned, writing for British and American periodicals about Caribbean, African, and Indian soldiers in the Royal Air Force (RAF) and African American troops in England. “The Negro in the Armies of Europe” was his first foray, comparing imperial attitudes toward recruiting colonial servicemen. Although Britain had come to rely on colonial recruits, it was only “dire expediency” that occasioned “the induction of Negroes into the British army.” “Only as cannon fodder or as an instrument in the fruitful Roman policy of ‘divide and conquer’ has the Negro been of interest to the English” (“Negro in the Armies” 9). Despite minor differences in attitude among the European powers, Walrond grimly contended that their practices were all meretricious and objectionable, even the French, who “too often used” black troops “to pull the white man’s chestnuts out of the fire” (“Negro in the Armies” 9).

Not everything Walrond wrote for The Black Man departed from Garveyism. “A Fugitive from Dixie” was a 1936 sketch about a sharecropper who fled Arkansas for St. Louis, where a “contact man” from an organization resembling the UNIA records his life story, a tale of intimidation by white men out to seize his crops and livestock. It celebrates the sharecropper’s indomitable spirit and the magnanimity of the organization, which finds him a job to support his family. Capably executed, the story exhibited Walrond’s skill with African American vernacular but was essentially a tribute to Garveyite ideals of race pride and masculine individualism. Another contribution hewing closely to Garvey’s principles was “Can the Negro Measure Up?,” an essay about the Enlightenment figure Abbé Henri Gregoire, “one of the early champions of the cause of Negro liberty.” It affirmed that “Negroes” could “measure up” to Gregoire’s high expectations, but more interestingly, it illustrated Walrond’s voracious historical imagination and contained some of his only recorded reflections on Haiti and Guadeloupe.

At this point, a pioneering volume of literary scholarship praising Walrond appeared in the United States. The Negro Genius, by Benjamin Brawley, claimed that he “excelled in the freshness of his material, in his clear perception of what has value, and in the strength of his style. […] One can only regret that he has not produced more within recent years.”39 Walrond shared this regret but as the foregoing discussion indicates, Brawley was not looking in the right places. Walrond had moved on, and the African American tradition could no longer claim him, if it ever could. For that matter, he had not quit fiction writing. In addition to “Fugitive from Dixie,” he published an exquisite story in The Spectator entitled “Consulate.” It was the third in a series of stories for mainstream London periodicals to feature Caribbean merchants or clerks as protagonists. Walrond was drawn to the dramatic potential of quotidian commercial spaces, setting stories in bodegas, brothels, beauty parlors, groceries, and restaurants. In these Caribbean tales, a petty bourgeois clerk plays a small but critical role fulfilling the lowly offices of empire. Clerks were useful for exploring the complexities of coloniality because they were neither the oppressor nor the oppressed, exactly. Often colonial subjects, they were not indigenous and did not identify with the peasants and laborers who comprised their clientele nor did they quite belong to the ruling elite.

In “Consulate,” a wry critique of empire is mediated by a sympathetic treatment of one of its middlemen, a consul’s clerk named Leon Cabrol. A “middle-aged man of color” from British Guiana, Cabrol suffered for two years in the “funereal climate” of Colón, leaving him “sallow, yellow-eyed, white-lipped” (305). Performing his duties processing ship manifests and the like, Cabrol is besieged by the demands of the diverse community. He accepts a cash deposit for a Jamaican bank account, records testimony from an eyewitness to an assault, signs the passport of a Chinese man returning home with his six children by a “tall willowy Negress.” Finally, he refuses a woman’s request to send her daughter back to Jamaica on account of insubordination. The mother storms out, “properly scandalised,” dragging the girl by the arm, and the story ends with Cabrol calling “Next!” and “scanning the slowly diminishing throng” (309). Like the grocer in “Inciting to Riot,” Cabrol is no innocent—he is implicated in the colonial project—but he is the story’s only individuated character and his predicament is treated as just that, a predicament, not an instrument of domination. The opening line describes him as “the arbiter of life and death” for Colón’s residents, but we are meant to understand the misery of adjudicating the messy, quotidian aspects of Empire as it is lived day to day. If empire does its worst damage to colonial subjects, he suggested, it also punishes its managers, on whom devolved empire’s most banal functions of discipline and regulation. “Consulate” anticipates Orwell’s “Shooting an Elephant,” a story about another middleman’s crisis of conscience, a “sub-divisional police officer” in Burma “hated by large numbers of people” who realizes in a terrible epiphany his complicity with oppression. But Walrond pulls up short of Orwell’s contention that such virtuous men might derail the colonial misadventure and expose “the real motives for which despotic governments act.”

The link to Orwell was more than thematic. A few months after “Consultate” appeared, “Shooting an Elephant” was published in the journal New Writing, and when Walrond sought to jumpstart his fiction career, he looked to that journal.40 He may have been emboldened by its mission “to further the work of new and young authors, from colonial and foreign countries as well as the British Isles.” From his flat near Tottenham Court Road, Walrond wrote editor John Lehman “to ask whether I may be permitted to send you a short story of about 3,500 words in length which deals with life in the West Indian Negro slum quarter of Brooklyn N.Y.” He rehearsed his credentials, conceding that “not much of my stuff has appeared in this country” despite his prior success in New York. Lehman showed Walrond’s story to a friend at the Hogarth Press, who recommended it for New Writing, noting, “I think this has a good deal of merit and originality.” But Lehman demurred: “Agreed it’s interesting, but it doesn’t come to anything.” Thus was Walrond’s effort to revive his fiction career on this side of the Atlantic thwarted again.41

THE KING V. ERIC DERWENT WALROND

Lehman’s characterization of the story—“interesting” but did not “come to anything”—also summarized the impression forming around Walrond generally. He was eager to disprove it and felt he had disappointed many people, but he was reluctant to seek help. His career was further destabilized when he came to blows with a coworker at The Black Man office in 1938. Walrond stabbed the man, was charged with “maliciously inflicting grievous bodily harm,” and although he was acquitted, spent nearly a month “detained on remand” awaiting trial. His arraignment was covered in the Westminster and Pimlico News, his trial at the London Sessions reported in The Times. It must have been a source of considerable distress.42 Conditions at the office were strained because Garvey’s wife, Amy Jacques, and their two sons, one of whom was gravely ill, had joined him in London, and his marriage deteriorated. Garvey described the office as “fraught with tension” and complained of his “inability to hire capable clerks.”43 In the summer of 1938, soon after his son was discharged from the hospital, Garvey left for a conference in Canada, instructing his wife to mind the office and the children. Their son’s health took a turn for the worse, and she hastily arranged passage back to Jamaica.44 It was during this tumultuous period, during an unseasonably hot week in early August, that the fight erupted between Walrond and James McIntyre.

Walrond had upset Garvey by flirting with the female staff, leaving the impression that he was “making love to all of them at one and the same time.”45 The particulars of the conflict with McIntyre are unclear because the newspaper reported only the statements of the defendant and the lawyers. McIntyre’s profession was given as a clerk, Walrond’s as a journalist, and their acquaintance was said to have been four years. McIntyre claimed Walrond spread a false rumor that he wished to leave to work “for another magazine for coloured men.” When McIntyre arrived one morning, Amy Jacques confronted him, at which point he stormed into Walrond’s office. He said Walrond “had been making insinuations against him, and recalled another occasion when he had made to his employer statements that were intended to be injurious to him. He warned him this must stop.” Walrond replied that he was “talking nonsense” and “came up to him in an aggressive manner,” at which point, McIntyre said, “I closed in on him.” In the ensuing struggle, Walrond fell and McIntyre claimed to have “waited until he got up.” But Walrond allegedly “whipped a knife from his pocket, rushed at [McIntyre], and slashed him on the right arm.” He inflicted a serious wound, the fight spilling into the hallway. “I closed in on him again,” McIntyre testified, “And while we were locked together I felt a stab in my back at the region of my neck. He struck me, and I fell down. I got up and rushed at him again. We continued struggling, and then he rushed down the stairs” and outside.

McIntyre denied having instigated the fight, but Walrond’s lawyer introduced doubt by asking about his other jobs, which relied on aggressiveness, strength, and intimidation. McIntyre admitted to having fought once as an “all-in wrestler,” and he had worked the door of a nightclub but never as a bouncer, only a “receptionist.” This nicety brought out the judge’s humor: “That is quite the opposite,” he quipped to the delight of the assembled. McIntyre’s case did not hold up at trial. He admitted to being “very annoyed” upon learning that Walrond told Garvey he was planning to quit, punching him in the face and breaking his chair. He denied having yelled, “I’ll teach you to carry tales about me,” and “Don’t fool around me, or I’ll kill you,” and denied further that Walrond only reached for the knife in self-defense. The fact that the weapon was a penknife, which Walrond said he carried for the professional task of clipping articles, helped exonerate him. His lawyer also maintained that McIntyre came at him “again and again, regardless of the fact that he was holding the knife” and was “mad with rage.” If Amy Jacques Garvey had been available, she would have been called to the stand to answer Walrond’s claim that she pulled McIntyre off him, but she was in Jamaica. He did not need her testimony and was acquitted on September 21, 1938. He did not contribute another article to The Black Man, which folded the following year, just before Garvey’s death.

EVACUATION

Perhaps the trial reminded Walrond of life’s precariousness, or he may simply have become desperate for income, but he swallowed his pride and in the spring of 1939 contacted Charles Johnson, now director of Fisk University’s Department of Social Sciences. Although neither Walrond’s letter nor the response survive, Johnson told Ethel Ray Nance he had finally heard from “the wandering one, after about twelve years.” “He seems to have been avoiding contact with persons he knew more out of sensitiveness about not keeping up the promise of Tropic Death than any other conceit. A note from you might on a long chance revive a flickering spark and yield something worth the effort,” Johnson suggested, giving Walrond’s address as 16 Fitzroy Street W1, London.46 The two conspired to assist him. Nance thought Walrond might get work as a foreign correspondent, but Johnson was not optimistic. Better to use his fiction to reconnect with American editors, he felt.

Walrond should have a story or two out of the past few years of living in Europe. It would help tremendously if there were a manuscript that could find its way to publication. He has been silent for a long time and these fresheners will be extremely helpful in restoring contact with the publishers and writers.47

Johnson knew a young sociologist headed to London and told him to look Walrond up. Horace Cayton, a prolific scholar who had coauthored Black Workers and the New Unions and would soon write Black Metropolis with St. Clair Drake, met Walrond twice, encouraging him to apply for a Rosenwald Fellowship.48 This proved impossible, not only because the fellowships were restricted to “American Negroes living in the United States, and to southern whites,” but also because Henry Allen Moe served on the Rosenwald selection committee, and as Johnson gently observed, “Eric did not quite come through as expected” on his Guggenheim.49

Nance coaxed an article from Walrond, likely an excerpt from The Big Ditch, and sent it to Johnson for circulation to his contacts, including The Atlantic Monthly, but it was not accepted. Thinking the editor’s comments may “be of some value to Walrond if he should ever decide to do any further work on his manuscript,” Johnson returned the article to Nance.50 “I find myself speculating upon the effects of the recent unpleasantness in Europe,” he added. He was referring, with characteristic understatement, to Germany’s invasion of Poland and the consequent declaration of war by England and France. Johnson wondered whether this might be the thing to get him “home.” “The prospect of war may prove for our errant litterateur something of a boon,” he wrote, “A recent radio announcement from England mentioned our Ambassadors’ and the Americans’ Clubs’ patriotic efforts to get back home Americans with insufficient funds for the trip.” He stopped himself, realizing his assumption: “Or is Eric American yet?”51 The West Indian immigrant who had never filed for naturalization could not avail himself of the provision. Nor did he follow the many West Indians returning to the Caribbean with the threat of war looming.

Walrond wondered whether evacuation was necessary and on September 1, as Germany invaded Poland, he wandered Bloomsbury, canvassing local opinion and reporting the results for the Amsterdam News. “I went to see about trains out of London” and “found that early in the morning orders had come through suspending all goods traffic on the railways.” The ticket clerk gave a stern caution: “If you haven’t anything to keep you in London, I’d advise you to take the 6:15 tonight. Tomorrow the Government is expected to take over the railways and all the train services will be curtailed.” Walrond confessed alarm. At the gates to the British Museum he spoke with an Indian friend, a novelist, asking how seriously to take the gathering war clouds. A Marxist, the novelist was skeptical: It was “all part of a grand show put on with the object of hoodwinking the working classes.” Around the museum, Nazis had previously lurked undercover, Germans whose identity was an open secret among patrons, but they were no longer about. Nor was the “young German” whom “all the museum staff knew to be a Nazi spy” in his place in Reading Room 1. Even the “buxom, middle-aged, always well made-up Fraulein who was not averse to taking tea at the lodgings of any Negro engaged in the colonial struggle was not there, either” (“Noted” 1).

Leaving the museum, Walrond stopped to chat with two West Indians, neither of whom seemed alarmed. The Barbadian, a recent convert to Communism, felt sure Stalin had averted war by signing a nonaggression pact with Hitler, a view Walrond found unpersuasive. The Trinidadian was confused by the prevalent fear of Germany, having just returned from a teaching stint in Berlin, where the people were nicer than in England and “the girls, the girls …” Advancing through Bloomsbury, Walrond checked the window of a Guyanese friend, a pilot who, despite having trained at the same aviation school as Charles Lindbergh, was denied a position in the RAF. “Will he get his chance now?” he wondered, “Will he be able to pierce the colour line now that war was imminent?” (“Noted” 10). With these conjectures on his mind, Walrond decided not to leave himself to the tender mercies of the German girls his Trinidadian friend promised or the Luftwaffe that might precede them. He boarded the train, joining tens of thousands of Londoners whose exodus was being hastily prepared for in evacuation centers around the country, the safe havens during what would be a war of immense, protracted brutality, reducing to rubble much of what had been Walrond’s hometown for eight years. By the time he returned eighteen years later, London would be transformed, not only by the war and its regimes of austerity and rationing but also by the decline of the empire and the arrival of West Indians in waves so massive as to make the 1930s seem like a trickle.

hat happened to Eric Walrond? The question had “been asked numerous times over the past several months by persons who remember the promising author,” reported the Baltimore Afro-American in 1935, “No one seems able to answer except that Mr. Walrond left about two years ago for Mediterranean points, and has been gone ever since.”1 The “unknown quantity,” as Wallace Thurman called him, had become still more reclusive. He had granted just one interview during his brief visit to New York, terse and guarded. “Rumors reached [Charles] Johnson from Europe that Walrond had squandered the [fellowship] stipends and written nothing.”2 Even his mother lost track of him, unable to answer the Guggenheim Foundation’s inquiries into his whereabouts. Gregarious by nature, Walrond withdrew and became “very successful at dodging people he didn’t want to know or that he didn’t want to talk with or meet.”3 On moving to London in 1931, he rented a room near the Crystal Palace, a suburb near Brixton. One of his fellow lodgers, an Indian student, struck him as a ridiculous type of colonial subject, performing Englishness, “swallowing hook, line and sinker all the Pukka Sahib nonsense of the British Raj” (“On England” 47). But a subtle shift was under way in London against this mentality. Still relatively small in number, emigrants from the colonies were finding common cause, organizing, and promoting independence. They also sought to end racial discrimination in Britain, the “colour bar.” Most of the newcomers were students, seamen, and laborers, but by the 1930s professionals, artists, and intellectuals began swelling the ranks. Their collective activity and energetic publication program helped bring the empire to its knees and pave the way for future generations calling themselves black Britons. The reclusive Walrond would write his way into this community.

hat happened to Eric Walrond? The question had “been asked numerous times over the past several months by persons who remember the promising author,” reported the Baltimore Afro-American in 1935, “No one seems able to answer except that Mr. Walrond left about two years ago for Mediterranean points, and has been gone ever since.”1 The “unknown quantity,” as Wallace Thurman called him, had become still more reclusive. He had granted just one interview during his brief visit to New York, terse and guarded. “Rumors reached [Charles] Johnson from Europe that Walrond had squandered the [fellowship] stipends and written nothing.”2 Even his mother lost track of him, unable to answer the Guggenheim Foundation’s inquiries into his whereabouts. Gregarious by nature, Walrond withdrew and became “very successful at dodging people he didn’t want to know or that he didn’t want to talk with or meet.”3 On moving to London in 1931, he rented a room near the Crystal Palace, a suburb near Brixton. One of his fellow lodgers, an Indian student, struck him as a ridiculous type of colonial subject, performing Englishness, “swallowing hook, line and sinker all the Pukka Sahib nonsense of the British Raj” (“On England” 47). But a subtle shift was under way in London against this mentality. Still relatively small in number, emigrants from the colonies were finding common cause, organizing, and promoting independence. They also sought to end racial discrimination in Britain, the “colour bar.” Most of the newcomers were students, seamen, and laborers, but by the 1930s professionals, artists, and intellectuals began swelling the ranks. Their collective activity and energetic publication program helped bring the empire to its knees and pave the way for future generations calling themselves black Britons. The reclusive Walrond would write his way into this community.