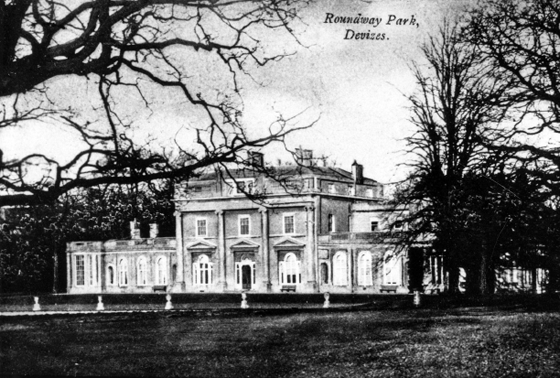

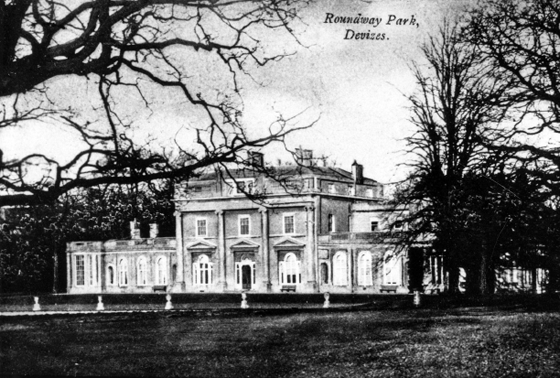

ric Walrond admitted himself to the Roundway Psychiatric Hospital after an unseasonably snowy spring. “South England Blizzard Chaos” read the local headline, and Walrond’s sun-drenched stories of Barbados, Guyana, and Panama accompanied him, unpublished, to his new home.1 The hospital, a massive complex on forty acres of land, housed thirteen hundred patients, many of whom were voluntary, like him. Formerly the Wiltshire County Asylum, it had been in operation since the Lunatics Act of 1845. For Walrond to acknowledge that he could no longer manage his illness required a good deal of courage and perhaps desperation. Patient records from this period were destroyed, but Walrond’s correspondence reveals the emotional stability and community he found there. Roundway was shabby and overcrowded but had practiced “a judicious combination of moral and therapeutic measures” since its inception.2 At a time when mechanical restraints and blunt coercion were still commonplace, the progressive Roundway staff believed patients recovered “by kindliness and vigilance, by ingenious arts of diversion and occupation.”3 A working farm, commissary, and laundry were staffed by patients, and a variety of clubs and activities kept them occupied. Teams competed in badminton and cricket against other hospitals. Walrond helped start a literary magazine, The Roundway Review.

ric Walrond admitted himself to the Roundway Psychiatric Hospital after an unseasonably snowy spring. “South England Blizzard Chaos” read the local headline, and Walrond’s sun-drenched stories of Barbados, Guyana, and Panama accompanied him, unpublished, to his new home.1 The hospital, a massive complex on forty acres of land, housed thirteen hundred patients, many of whom were voluntary, like him. Formerly the Wiltshire County Asylum, it had been in operation since the Lunatics Act of 1845. For Walrond to acknowledge that he could no longer manage his illness required a good deal of courage and perhaps desperation. Patient records from this period were destroyed, but Walrond’s correspondence reveals the emotional stability and community he found there. Roundway was shabby and overcrowded but had practiced “a judicious combination of moral and therapeutic measures” since its inception.2 At a time when mechanical restraints and blunt coercion were still commonplace, the progressive Roundway staff believed patients recovered “by kindliness and vigilance, by ingenious arts of diversion and occupation.”3 A working farm, commissary, and laundry were staffed by patients, and a variety of clubs and activities kept them occupied. Teams competed in badminton and cricket against other hospitals. Walrond helped start a literary magazine, The Roundway Review.The inaugural issue coincided with his fifty-fourth birthday and included a reflection on his peripatetic life, “From British Guiana to Roundway.” He praised Roundway warmly: “It is a far cry from British Guiana and Barbados, Colon and New York to Wiltshire. […] The jump, for a ‘depression casualty’ in the years following the Wall Street crash of 1929, is almost frightening.” What he found at Roundway was solace, “a compact, almost self-contained community set in surroundings of rare beauty,” “astonishing examples of brotherliness and self-sacrifice.” These remarks are more poignant when one considers the difficulties facing West Indians, who were arriving in England by the hundreds. The Guyanese politician Eric Huntley wrote to his wife of alienation and uncertainty, calling London “a lonely place for us colonials, not only from the point of view of our own senses but also as part of a cold and sophisticated environment.” “Alarming” rates of unemployment left “scores of coloured people loitering around” the East End, “possessing an air of nothing to do.”4 For Walrond, Roundway was a refuge and a form of asylum.

10.1 Postcard of Roundway Psychiatric Hospital, c. 1950, photographer unknown.

Courtesy of the Wiltshire & Swindon History Centre, Chippenham, UK.

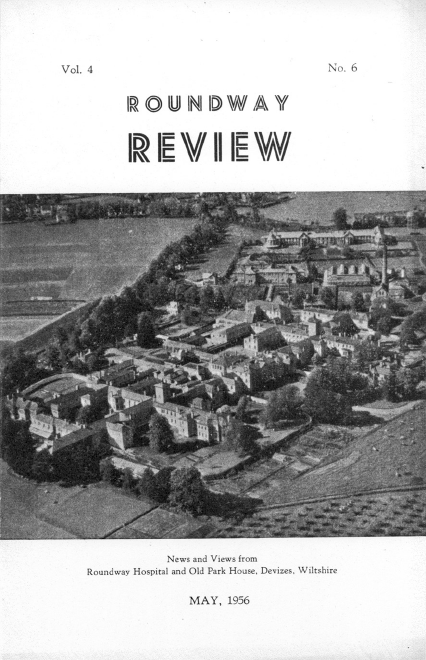

Every third Wednesday of the month from December 1952 through December 1958, The Roundway Review published articles, sketches, notices, and puzzles, all contrived to keep contributors diverted and readers entertained. A lofty mission statement declared its intent “to encourage free expression of ideas.” The hospital’s management committee exercised official oversight, appointing an editor from the staff, while Walrond served as assistant editor. He was its most active contributor, publishing regularly until his discharge in 1957. Early issues were amateur productions, typescript on sheets fastened with staples. Production values began improving a year later, when the hospital, persuaded of the journal’s quality and salutary impact, funded typeset printing. Forty of the first fifty issues contained Walrond’s byline.

A year in, he felt confident enough to contact Henry Allen Moe, alerting him to his publications and hoping Moe would publicize them in the Guggenheim Foundation annual report. He declined to explain the journal or his new residence, and Moe responded that it was good to hear from him but wondered whether Walrond lived at a hospital: “Will you be so good as to let us know if the address to which we are writing is your permanent address?” A delicate question delicately phrased. “I might say that until further notice I can be reached here,” Walrond replied, “I might also say that since May of last year I have been a voluntary patient in this Hospital.” He was encouraged to have renewed this correspondence and further cheered by a visit from his eldest daughter, who was visiting England from Jamaica with her husband.5 However, he contacted Moe only once more during his stay, listing additional work to “show that I am still endeavouring to adhere to the project which I submitted to you with my application for a Fellowship.”6

Most of his Roundway Review publications were Caribbean stories written over the previous fifteen years. They were redolent with tropical scenery, urban and rural, and burst with polyphonic voices. Tracing his successive relocations, the first stories were set in British Guiana, the next in Barbados, followed by Panama stories, a tale about Caribbean Brooklyn, and a handful set in England. Interspersed incongruously among them were his accounts of the hospital facilities, from the commissary to the laundry to the farm. These explanations of ironing and the baking of lardy cakes seem odd alongside his literary publications, but they reflect his affection for the place. Most incongruous of all, however, was The Second Battle, a detailed treatment of the French canal attempt in Panama that spanned fifteen issues. It is the only surviving remnant of The Big Ditch. Meticulously researched, The Second Battle constituted a formidable encounter for readers of The Roundway Review, its installments sandwiched between accounts of the pleasant outings staff and patients had enjoyed to a local dairy, library, or apple orchard. There is something at once wonderful and tragic about the juxtaposition in these pages of some of the earliest Caribbean stories published in England and a startling work of colonial history, alongside other patients’ tributes to the hospital band and reminiscences about a favorite horse at a nearby farm.

IN SEARCH OF LOST TIME

Caribbean discourse is characterized by a relay, Edouard Glissant has argued, by detour and return. “Detour is not a useful ploy unless it is nourished by return: not a return to the dream of origin, to the immobile One of Being, but a return to the point of entanglement (point d’intrication), from which one was forcefully turned away; that is where it is ultimately necessary to set to work the elements of Relation, or perish.”7 Returning from his extensive detour to the point of entanglement, Walrond wrote a genealogy of the present, publishing thirteen stories in three years.8 Their literary quality is uneven, but their flaws and eccentricities are symptomatic. Walrond’s characters grapple with vexing questions about the cultural inheritance of multiply colonized peoples, marked irrevocably by the social and political upheaval of their communities. Their embodied knowledge is expressed through their accents and idioms, their injuries and desires. Woven through the stories is a theme of personal vulnerability and dependence on others. “There but for the grace of God go I,” they seem to sigh, their author scarcely believing he had survived the events they recount.

Although they are framed as fiction, “The Servant Girl,” “The Coolie’s Wedding,” and “A Piece of Hard Tack” depicted Walrond’s own cloistered and pampered childhood in British Guiana. Their theme of innocence succumbing to experience is a universal one, but their setting is a distinctive society shot through with race and class differences, an assemblage of plantations, small farmers, and merchants populating the urban coastline, beyond which lay a vast interior. There are three versions of otherness in relation to which Walrond’s character finds himself defined: South Asians, indigenous people, and “barracks” boys who share the narrator’s nationality and complexion but not his temperament, a reticence augmented by class privilege. In each story, the protagonist strays beyond the home in which his mother and the maid coddle him. Perched high above the dank soil, the house is a feminine sphere, alternately comforting and constraining. At this remove he is safe from danger—street urchins, diseased vagrants, “heathen coolies,” iguanas, eels, bats, and “duppies.” But he is also prevented from maturing through contact with the adult world and socializing with other boys, insulated from their codes of incipient masculinity.

Beyond the front gate was a community seething with social difference. The space beneath the protagonist’s house was a squatting ground for an elderly Indian, a “coolie” who had outlived his utility on the plantations. “Foot-loose vagabond!” the servant girl called him, “Stinkin’ up the place” with cow-dung cooking fires (“Coolie” 22). He had a speck of white in his eye and chanted, “Akbar-la-la, Akbar-la-la, Mahaica is comin’ down.” Although the servant girl ridiculed him, Walrond’s narrator felt the song reflected his acculturation: the Mahaica River flooded in the rainy season, and he speculated that the squatter’s fear of its “overflow had already become part of his existence in Guiana.” The child’s interest in the acculturation of Indians becomes more evident when, later in the story, he encounters a wedding party, an Indian bride and groom on the way to a church ceremony. As their carriage advances, an accident occurs, the horses dumping the carriage and its passengers into a canal. A “crowd of Negro women” witness the spectacle, their “white calico skirts billowing out,” but offer no assistance. “‘Hey,’ breathed a female onlooker as though recovering from a shock, ‘Fancy Babus goin’ to the Church of England and gettin’ married! Whuh they think they is, nuh?’ And as the landau rocked and rolled, sinking deeper in the mud, no one offered the bride and groom a helping hand” (“Coolie’s” 23). Walrond declined to put too fine a point on it, but the irony is that the West Indians—themselves newcomers to British Guiana—show their neighbors such contempt. The story’s appearance in England just as West Indians and South Asians began laying claim to English institutions lent further poignancy.

Walrond fictionalized his transition to Barbados in “Two Sisters,” published in installments. It follows Henry, who moves with his mother back to her home island after several years in British Guiana. Although Walrond had siblings and Henry does not, the story otherwise reflects his life, from his house and school to the church where his mother worshiped. Henry’s father “was not converted and he was not with her”; like William Walrond “he’d gone to Colon; so there would be much eyebrow raising” (i, 19). Unresolved animosity between the titular sisters drives the story’s plot, but its force is the narrative voice itself, evoking the area of Jackman’s Gap near Bridgetown with vigor and precision.

The marl was restive, moving in billowing clouds to and fro, spiraling up and up and powdering as it lazily descended the blue sand, the sweet potato vines and the gaping mouths of myriads of soldier crabholes in the dune on the opposite side of the road. Further down the slope, blotting out the beach, the log cabins of Negro fisher folk appeared amidst the dark foliage of machineel trees; but in a clearing below the rum refinery the sea rolled in upon white and golden sand. Nets lay outspread in the sun between overturned fishing boats undergoing repairs. The tall, smokeless chimneys of the refinery loomed across the flickering green dome of the sea as though to dispute the passage of a flying fish fleet serenely tacking in the Bay.

Bessie down

For the sake of the pumpkin

Bessie down (“Two Sisters” iii, 19).

The passage closes with a ring game, the girls’ voices interrupting Henry’s reverie.9

Two of the four Panama stories in The Roundway Review depict an adolescence like Walrond’s in Colón, while the others cast a “Silver Man,” a West Indian laborer, as the protagonist. Each demonstrates the volatility of intercultural contact there, indicating the destabilization of race and class. Anxieties about that destabilization were expressed in racial epithets and casual stereotyping, but it also made possible realignments of interest and association, including, for our young Bajan, the opportunity for a white-collar job. The Silver Man stories are at once celebrations of this figure, whose labor built the canal, and object lessons about what might have befallen the author had he not met with the kindness of strangers. Throughout, Panama is depicted as enigmatic—highly racialized yet complicated by associations among migrants, their contact mediated by the Jim Crow regime of the U.S. occupation but continually exceeding that frame.

West Indian acculturation is the subject of “The Iceman,” whose protagonist was reduced to pushcart peddling after a leg injury cut short his career as a railroad brakeman. The story is not strictly autobiographical, but it takes place in Bottle Alley and meditates on what might have become of Walrond had he stuck around. The legend of the “Panama Man,” his fine suit and hat gleaming brighter than his watch chain, had its counterpart in the laborer who stayed on after the canal opened. Those who survived were rarely unscathed. “The Iceman” features one amputee, Natty Boy, whose leg was crushed by a train, and another who lost a leg in a dynamite blast. Rather than blame the Isthmian Canal Commission (ICC) for imperiling canal workers, Walrond attributes Natty Boy’s injury to his affinity for risk and an implacable desire to perform his job with flair. It was the challenge that gave the work pleasure, and Natty Boy took pride in it, performing like a matador. As he anticipates his treacherous dash to the switch, laborers gather at the train car windows to witness the spectacle. But Natty “was not putting off the moment to impress anyone with his fearless courage. […] Something else of which Natty was but vaguely aware, something connected with the mastery of a new craft, was involved” (24). But this time he took a risk and missed; “with an ominous jangling of the couplings the train leapt forward under a sudden burst of speed and shook him off. He stumbled and fell on to the rail and the wheels of trucks Nos. 9 and 10 passed over his right leg, shattering it just below the knee” (25). Intentionally or not, Walrond had written a story about his own career, cast in a different register. His fervent desire to “master a new craft” had propelled him to propositions far riskier than he realized, and as he sat in the hospital, he might have seen his protagonist’s fate—chipping blocks of ice to hawk in the blistering Panama sun, where once he accomplished feats of derring-do—as a figure for his own diminished condition, peddling Caribbean sketches in an indifferent land.

He recognized, of course, that he had enjoyed privileges that were unavailable to Silver Men, and the other Panama stories acknowledged his fortune. “Bliss” and “Wind in the Palms” each feature an adolescent “chombo” who makes good on a combination of charisma and luck. The conventional wisdom was that someone of his complexion had to pay his dues and behave with unstinting deference toward his social superiors. But these protagonists defy expectation simply by securing white-collar jobs in the ICC, the first rung on a ladder of success seldom extended to Panama’s West Indians. Taken together, the stories trace his path from circumscribed West Indian communities into a multiethnic mainstream, each step a springboard to the next. Few readers of The Roundway Review would have recognized the Caribbean diaspora memoir unfolding obliquely in its pages.

Of the Roundway Review stories set in England, two are almost indecipherable and two are evocative but slight. “A Seat for Ned” and “Cardiff Bound,” both set in subterranean poker rooms in Soho, are rich in atmospherics but finally yield more heat than light. “The Lieutenant’s Dilemma” and “Strange Incident” are parables set in Wiltshire during World War II, when residents encountered African American troops. All four stories are autobiographical; one is set, for example, in “a town on the Wiltshire Avon to which I’d moved from London on the evening of the day Hitler’s ultimatum to Poland expired” (“Strange” 45). Walrond depicted life among colonial seamen kicking about London’s West End awaiting assignment in the late 1930s in “A Seat for Ned” and “Cardiff Bound.” He may have been the first to attempt their portrait, but the stories amount to little more than character studies haphazardly assembled at a poker table. Like McKay in Banjo, Walrond sought to portray a community and idiom largely hidden from middle-class readers, and he seems unsure what to make his characters do. They eat curry with rice, leering and gesticulating through various states of inebriation, all narrated in the clipped prose of hard-boiled fiction. A hint of concern is registered for what lies ahead in old age for these toughs, but thin storylines make it hard to read these tales of London’s colonial underworld as more than nostalgie de la boue.

10.2 Cover of the Roundway Review, May 1956.

Courtesy of the Wiltshire Museum and Library, Devizes, UK.

By contrast, “The Lieutenant’s Dilemma” and “Strange Incident” lead unerringly to a polemical point. A white lieutenant’s dilemma is precipitated by the decision of his African American soldiers to boycott a Wiltshire town modeled on Bradford-on-Avon. One soldier takes the narrator, Walrond’s surrogate, into his confidence on the matter, discussing it at the pub.

Gently inclining himself toward me the G.I. lowered his voice. “You know how it is with the people in this town,” he said, rolling his eyes away from me and over in the direction of the five other people in the room. “‘Hello, darkey,’ ‘Good morning, darkey,’ ‘Oh, mummy, look at the darkey soldier!’ ‘Have you got any chewing gum, darkey?’” He paused, sat upright and stared ahead of him. “Well, we’d had enough of that ‘darkey’ stuff. We went to the company commander and told him we weren’t going to have any more of it. We wanted to be sent back to the States.” (135)

The narrator sympathizes, but he discourages the soldier from reading malicious intent into the townspeople’s behavior. The men soon realize that two white officers are watching them vigilantly. Their apprehensions subside, however, when the lieutenant strides casually to their table and buys the soldier a drink. The gesture suggests that the lieutenant is overcompensating for the soldier’s feelings of discrimination, hoping to soften his militancy on the boycott.

“Strange Incident” locates color prejudice in the U.S. military, carefully keeping Wiltshire residents above reproach. It is an unimpressive sketch, but it illuminates Walrond’s everyday life. A November 1943 afternoon running errands goes sour when white American officers accuse the narrator of stealing his own shoes from the U.S. military. Despite being one of the few nonwhite regulars in this town, the narrator had good relations with the locals. A clerk in the department store that fills his book orders is described as having “golden hair and an invariably polite smile” (44). He notices “a surprisingly large number of American military police,” “conspicuous in their white helmets and white armbands,” but does not give them a thought as he proceeds—a visit to the doctor, a stop at the reference library, and a cup of tea. However, two American officers accost him, demand his identity card, and ask, “Do you live around these parts?”

“We’ve had a complaint that you are wearing U.S. Army shoes. Are you?”

“I don’t think so,” I replied.

I glanced down at my shoes. They were an old pair of brown utilities I had purchased from a well-known firm of boot and shoe dealers in a West Country town.

“Who made the complaint?” I said.

“The U.S. military police.”

“I see.”

“They said you sounded when you walked as though you were wearing U.S. Army shoes.”

For a moment I contemplated the shoes. What was it that I had done, or omitted to do to them that had made them sound on the wet, shining pavement in the darkness of an early November evening as though they did not belong to me? I looked up at the officer. It was plain from the expression on his face and in his eyes that he did not believe my story. (45–46)

The narrator is exonerated, but not before the humiliation of detainment by a young soldier with a blonde crew cut and an examination by his commanding officer. This mistreatment is sharply contrasted with the behavior of the Wiltshire locals, who remain quietly loyal: “How did you get on?” whispers the woman who served tea. “It was a case of mistaken identity,” he says, to which she replies, “I thought so.” When Walrond had submitted “Strange Incident” for The Monthly Summary, Charles Johnson declined to print it, probably because it is less a report than a narrative. But it is a provocative account of one unstable racial regime colliding with another, and it articulated something that was widely felt but seldom expressed by people of color in 1950s Britain: “What was it that I had done, or omitted to do to them?” (46). These sketches suggest that Walrond made his peace with Wiltshire County, but one wonders whether his precarious mental health faltered under the casual racism he identified in “The Lieutenant’s Dilemma” or the sensation “Strange Incident” documents of being an intriguing “exotic.”

So, why did he stay so long in Wiltshire? Why had he not returned to London, New York, or Paris, or moved elsewhere? One reason was dwindling resources. He lived on very little after the war and had no career prospects. One can imagine the resignation with which a depressive met these circumstances. The other reason, at least as urgent, was a profound sense of shame at having lost his way, disappointing friends, supporters, and himself. The Monthly Summary folded in 1948 when Johnson became the Fisk University president, and Walrond’s 1950 story in Arena had not led to further publications. But there was one redemptive measure he could safely attempt from inside the hospital. Having published stories that traced his life from the Caribbean to England, he returned to the project on which he had worked fitfully for decades. The Roundway Review was not what he had in mind for The Big Ditch when he secured Liveright’s “unencumbered rejection” in 1931, but any forum was preferable to letting it collect dust in the closet of a mental hospital.

What resulted was The Second Battle, an epic history of the French attempt at the Panama Canal and the plight of its director, Ferdinand De Lesseps. The narrative had a hero, a mixed-race Panamanian lawyer who led a populist rebellion as the French canal scandal exploded. It also had a villain in the charismatic but monomaniacal De Lesseps, who ruined small shareholders in France; manipulated politicians, the media, and the Paris stock exchange; and subjected thousands of laborers to malaria and yellow fever. However, there was one respect in which Walrond resembled De Lesseps, and it could not have been lost on him as he sat in the hospital revising the manuscript. The title he chose referred to a pronouncement De Lesseps made after the Inter-Oceanic Canal Congress selected him to lead the Panama project. He had won acclaim by directing the Suez Canal operation, accruing wealth and public adulation. “When a general has won a battle,” he said, “if someone proposes to him to win a second one, he never retreats.”10 Walrond knew the way this story ended, in abject failure. But he also knew the extraordinary resilience and resourcefulness De Lesseps showed in the face of adversity. He went down with the proverbial ship, and the fact that his second battle failed so spectacularly after his first triumph added to the pathos. The author whose first book was celebrated as a triumph of New Negro fiction had failed spectacularly at his widely anticipated second effort, but by publishing something of it now he would prove, to himself if no one else, that he too refused to retreat in the face of adversity.

THE SECOND BATTLE

Walrond’s history of the French attempt at an interoceanic canal was like the project it chronicled: audacious, often magnificent, but structurally compromised. He knew that the U.S. success had eclipsed a story that was equally fascinating and complex. The independence movement that severed Panama from Colombia developed during the French project, rebellion flaring into open revolution. The role the United States played during this crisis allied the Panamanian elite with the “Yanks,” in whose hands they placed their land and economic future. The catastrophe that befell the French was not just a case of hubris or mismanagement, nor was it simply a casualty of the pestilential scourges that beset the workforce. A volatile political climate, an influx of West Indian laborers, and a calculated display of U.S. military force conspired to undermine the French. Moreover, Walrond recognized in the Inter-Oceanic Canal Company an experiment in a new colonialism, an undertaking that hearkened back, in one sense, to European stockholding companies but anticipated the business imperialism of the twentieth century, when corporations called the shots and it was no longer expedient or necessary to occupy territory by force. This was a pivotal transition, he felt, a story that needed telling.

When he contracted for The Big Ditch, the market was clogged with books about the canal. He sought to write a different kind of history, drawing on his multilingualism and familiarity with the region. With the help of a capable editor he might have pulled it off. Its only remnant, The Second Battle, attests to Walrond’s ambitious vision and prodigious research. He examined as few others could the peculiar confluence of developments in France, Colombia, and the United States that thrust Panama into modernity. But he had trouble seeing the forest for the trees. Bursting with data and quotations, The Second Battle is more narrative than argument, and the narrative is circuitous, inverting chronology. It begins with the demise of the project and the repatriation of thousands of Jamaicans in the late 1880s, steps back to the project’s conception and funding scheme, then moves abruptly to the problems facing the French in the mid-1880s, as public mistrust mounted at home and turmoil erupted on the isthmus. Thereafter, Walrond trains his focus so narrowly on Panamanian politics and military maneuvers that one wonders what happened to De Lesseps and the Frenchmen he featured earlier. Because he was discharged from Roundway Hospital before publishing the manuscript’s final installments, it is difficult to judge its overall coherence. What was published suffers from the absence of a steady editorial hand that could have realized its potential.

Readers expecting a frontal assault on the white man’s incursion into Caribbean territory would be disappointed by The Second Battle. As in Tropic Death, Walrond was eager to distance himself from an explicit ideological agenda. Just as he felt the best case for the “Negro’s” talent at fiction writing was to suppress overt propaganda and sentimentality, so in this project he pursued a standard sort of historiography. He tasked himself with investigating the machinations at the Paris bourse with the same punctiliousness as a French historian; he examined the anti-Semitism behind attacks on the canal project’s management; he discussed the diplomatic efforts of U.S. secretaries of state; and his references to U.S. Marines omitted the sunburned necks, blonde crew cuts, and pistols that appear elsewhere with baleful frequency. In these ways, he inoculated his work against the appearance of provincialism and partisanship. Indeed, his stated theme strikes the keynote of liberal history, “the struggle between democracy and dictatorship which occasionally flared into violence” (ix, 41). He left implicit the subversive conclusion toward which his evidence pointed, that the 1880s political crisis “firmly established that the real power on the Isthmus was the U.S. military.”11

However, in this effort to perform conventional liberal history, The Second Battle fails to conceal the traces of its author’s radicalism. Much as Walrond sought to suspend his authorial voice above the fray, he saw in Panama an exploitative rivalry among imperial powers, a view that becomes evident in that most novelistic of devices: characterization. An unholy trinity of Colón residents—Pedro Prestán, George Davis, and Antoine Portuzal—commits what is ostensibly the worst atrocity in The Second Battle, the near total immolation of Colón. The fire, which reduced hundreds of homes and businesses to cinders, left ten thousand homeless, and destroyed a million dollars of Inter-Oceanic Canal Company property, is attributed to the rashness and bravado of these rebels. But they are without question the narrative’s most compelling figures. They are intemperate but populist to their bones. They are virulently anti-American but only because their vision of Panama for Panamanians defies the clutches of any distant power, whether Bogotá or Washington. They represent the vibrant Pan-Caribbean society of the isthmus: Portuzal a Haitian “mulatto,” Davis a Jamaican, and Prestán, the rebel leader, a lawyer and statesman of mixed Panamanian and West Indian ancestry. Is it any wonder that Walrond, advocate of self-determination for the world’s people of color, fails to condemn them persuasively?

He waves in that direction, to be sure. The U.S. suppression of revolutionary forces is cast as a victory for law and order, a saving throw that prevented Panama from descending into an anarchy that opportunistic European powers would have exploited (xiv, 158). We are asked to imagine that the United States arrested an “almost unbelievably sinister trend,” preserving Panama for delivery into the protection of Theodore Roosevelt, not France or Spain. The problem is that the revolutionary energy of the Prestanistas does not come off as “almost unbelievably sinister.” They are overmatched but cunning, negotiating to advantage and refusing to surrender. They are nobody’s puppets, while the troops that subdue them are reinforcements from Bogotá and the United States, not Panamanians. Their disdain for Colombian authorities is represented as reasonable, with President Nuñez having abrogated the 1863 constitution. Nor was the unrest confined to Panama, flaring also in Chiriqui and Santander. Prestán was acquitted of a murder charge in the early stages of the uprising, and when his release was delayed the Panama state legislature passed a resolution declaring “that all parties who have been interested in keeping Mr. Prestán in prison shall be tried and punished according to law” (viii, 280). If Prestán was a militant rebel, in other words, he enjoyed the widespread support of a rebellious citizenry.

Walrond calls Prestán many unflattering things—“the most controversial figure thrown up in the Colombian civil war”; fond of “gun play” and “notoriously quick on the draw”; “a destructive influence”—but he could not disguise his admiration for the man (viii, 275–79). He loved a trickster, and Prestán was as expert as they come. Hiding from the Colombians as a murder suspect, he “masqueraded as a Chinese fishmonger” (viii, 280). On the lam after the burning of Colón, he escaped by impersonating a woman. He was a shrewd negotiator, arranging for the delivery of a massive arms shipment from the United States, and a bold adversary, taking American officials hostage when the arms shipment was detained in the harbor. Moreover, Prestán advocated for the Jamaican laborers who came to Panama in increasing numbers. The Colonial Office put the migration of Jamaicans at 22,480 in 1884 alone, two thousand more than the entire population of Panama City (vii, 256). Peak migration from Jamaica coincided with the highest mortality rate among canal employees in the French era, Walrond notes, in excess of twelve hundred deaths that year. His research revealed massive layoffs and an increase in “idleness” and “discontent,” “too many men chasing too few jobs” (vii, 257). If Prestán and his rebels were an unsavory, impetuous lot, as Walrond said, his account legitimated them by illustrating the conditions requiring their intervention. Walrond’s Prestán elicits our identification despite the pretense to discredit him.12 For this reason The Second Battle is at odds with itself, alternately disparaging the rebels and celebrating their resilience and popularity. They act decisively and with conviction, while the Loyalists in Bogotá dither and bang at the telegraph, waiting for the French or Americans to impose order.

There are few sympathetic figures in The Second Battle. Officers and engineers come and go, and Panamanians are maneuvered around the theater of war like chess pieces. Only when writing about Prestán and his comrades does Walrond use free indirect discourse, a novelistic device aimed at generating intimacy with a character. Its effect is produced by introducing a character’s thought and speech patterns into third-person narration. In The Second Battle, “As the party turned out of Lagoon into Fifth Street, Prestán paled with anger at the sight before him. Instead of the merchant ship Colon the U.S. gunboat Galena lay beside the wharf! What was in the wind? When had the switch been made? Didn’t anyone ever tell him anything? Everything seemed to be tumbling down on him at once” (ix, 44–45). The third person is not relinquished, nor is Prestán quoted, but rhetorically the passage follows his consciousness, the narrator throwing his voice. The only other figure with whom Walrond uses this device is George Davis, Prestán’s lieutenant. Led to the gallows, he is stoic, dignified. Shouts of “Incendiary! Assassin!” rain down. “Had he not heard the words and sensed the undercurrent of hostility?” Walrond asks, “Had he not heard the click of a photographer’s camera upon his appearance in the crowd, manacled, flanked by the rifles and bayonets of Colombian soldiery? Had he not been spat at? He would show them that he knew how to die!” (xiv, 160). No one believed Davis or Portuzal had set fire to Colón; it was understood that they were scapegoats. But as Walrond emphasizes, they met their executions stoically: “Having refused to have their eyes bandaged, the men stood looking into the setting sun as the nooses were carefully adjusted under the left ear of each” (xiv, 160). Such efforts at characterization, coupled with free indirect discourse, enhance our admiration and identification, superseding the narrative’s claims about the illegitimacy of the Prestanista cause.

The Second Battle is thus a perplexing document in both its argument and its structure. What it seeks to demonstrate is the confluence of events that undermined the French effort, from the gross miscalculations of its director, to the epidemics of disease, to the Colombian crisis in which the project was mired. In that fatally weakened state, it could not advance independent of the French government, as was De Lesseps’ fervent hope. He was compelled to “eat humble pie” and ask his government to issue lottery bond bills, a plan that failed miserably (v, 204). He died a broken man, convicted by an irate Paris tribunal, his family’s good name tarnished and his fortune squandered on a disastrous effort to create a sea-level canal with private financing. But Walrond told a broader story than the De Lesseps tragedy. It attended to the tension between the activities of the Inter-Oceanic Canal Company as a private stockholding company and the affairs of the governments interested in the outcome. This was an important test of a modern form of imperialism, one shorn of territorial possession, occupation, and other established practices. Had it succeeded, De Lesseps’ canal would have redounded to the immense credit and profit of France, of course, but it would also have vindicated this vision of world affairs orchestrated by finance capital. Although the French failed, the lessons were not lost on the United States, where many in the private and public sector were poised to pick up where they left off. Precisely in its wedding of finance capital to state and military interests, the U.S. initiative would avoid De Lesseps’ costliest errors.

Although Walrond was discharged before publishing The Second Battle in its entirety, there is a kind of poetic justice in its truncated appearance. The fifteenth installment was devoted to the “Culebra massacre,” a bloody confrontation during the drawdown of troops after the revolution was suppressed. Culebra, situated at the highest elevation, presented the most difficult challenge of the excavation and was subject to massive flooding. The French contractor was involved in “an industrial dispute” with its Jamaican workforce. Colombian troops were called in and, keyed up from their victory over Prestán, dealt aggressively with the laborers, killing eighteen and wounding twenty. “Owing to the sanguinary nature of the occurrence and the conflicting evidence of ‘eyewitnesses’ it was at first difficult to obtain a true account of what had happened,” Walrond writes (xv, 182). But investigations of the British Colonial Office clarified where responsibility lay, calling the attack “unprovoked” and declaring “the lives of British subjects on the Isthmus insecure.” The massacre of Jamaicans demonstrated “the absence of protection for life and property” in Panama, warned the Colonial Secretary (xv, 183–84). Colombia’s Supreme Court soon convicted the commander who ordered the attack, Walrond adds. It was an apt way to end publication, addressing the plight of West Indian laborers. The Second Battle presents itself as a work of conventional liberal history and it almost succeeds. But it continually produces signs of what it suppresses, the sympathetic identification of its author with the dispossessed, the politically militant, and the Afro-Caribbean.

TREATMENT AND DISCHARGE

The process of what Roundway Hospital management called “modernisation” included new treatments such as prefrontal leucotomy, a surgical procedure used sparingly in cases of severe mental illness, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), which came into use for treatment of depression in the late 1940s. “The general results of ECT have been most satisfactory,” wrote the superintendent, “and in some cases of great benefit.”13 It was used increasingly during Walrond’s time at the hospital, and although it may seem cruel to have induced epileptic seizures in patients, it must be recalled that this was just prior to the advent of antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs. Whether Walrond’s depression was severe or persistent enough to warrant ECT is unclear, but considering the superintendent’s enthusiasm—“a most useful form of treatment for depressed patients,” he called it “safe and effective”—it seems possible.14 The muscle relaxant curare was administered in conjunction with ECT to minimize muscle spasms, and the grisly irony would not have been lost on Walrond that he had traveled all the way to Wiltshire to be injected with a Guyanese plant toxin. Psychotherapy, practiced extensively at Roundway, may have proven an adequate palliative, or he may have taken largactil, the hospital’s first “tranquilising drug.”15 What is clear is that he felt best when active and intellectually engaged. A security officer provided the only firsthand recollection of Walrond’s tenure: “I knew Eric very well during his stay. I always found him a very nice fellow. He was never confined to ward, he was very helpful in everyway and was well liked by his fellow patients and by all the staff.”16

Because Walrond had neglected or estranged friends and colleagues, it was unlikely that anyone would revive his career, but that is what happened. Nancy Cunard had been upset that Walrond failed to deliver a promised essay for her Negro anthology, but in the twenty years since she had apparently forgiven him. When he wrote her in 1954, enclosing a copy of “Success Story,” she thanked him, feeling struck “once again—how well you write” and impressed by its “fantastic overlays of the Antilles and U.S.” But “what can you be doing in that hospital?” she wondered, “I wish I had known where to get in touch with you when I was in England all last winter.”17 He had reclaimed her favorable attention. She wrote again to reiterate her praise, expressing eagerness to meet in London.18 The hospital’s policy was to release him for short trips if he requested permission. “Please let me know when we shall meet,” she wrote. Reflecting on the growing West Indian immigration to England, she proposed they write something collaborative on this “matter of national interest.” “You, as usual, will know a great deal about all of it. I wonder if there would be grounds for some kind of ‘open letter’ on the subject in one of the weeklies? I mean, correspondence, or articles answering each other—IF there is enough interest, this might we do?”19 Although the proposal did not come to fruition, Cunard was in earnest. “I want to hear more about your stories—or book!” On her next visit to London, she contacted him. “Where are you dear Eric?” she wrote from the Hotel Whitehall, “Please send a line here and come and lunch soon.”20

Cunard’s first letter mentioned that Harold Jackman had established the Countée Cullen Memorial Library at Atlanta University. Walrond wrote Jackman immediately: “I understand that you need material,” “all of it Negro.” He was moved by Jackman’s initiative.

10.3 Photograph of Langston Hughes and Nancy Cunard, Paris, 1938.

James Weldon Johnson Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

I was very touched to hear about this proof of your loyalty to Countee whose death […] came as a profound shock. It’s a splendid thing you are doing to try to keep his memory alive and I should like to do something to further the effort. Unfortunately, my belongings are scattered all over the place (in New York and in Bradford-on-Avon where I have been living since 1939) and it will be sometime before I can send you anything.

Contact with Jackman reconnected Walrond with a world he had long since left behind. “Whatever became of Jean Toomer?” he wondered. “Did the death of his wife, Margaret Latimer, hit him so hard that he took a kind of Oriental vow of perpetual silence? Or has he moved so far across the colour line that he has become practically invisible?” He assured Jackman he was well despite his return address: “I have been in the hospital for over two years now but at present I’m fine and still writing. Under separate cover I’m sending you a story which has appeared in the hospital magazine. It’s a yarn (‘Success Story’) in six parts. I hope you like it.” He pledged to “keep in touch” and send “from time to time anything that may be of value to the Atlanta collection.” He stayed in contact with Jackman until May 1959.21

Another of Cunard’s contacts led to Walrond’s discharge from the hospital. Out of the blue in May 1957, he received an inquiry from Erica Marx, director of the Hand and Flower Press. She asked Cunard for help with a “Negro poetry” performance she wished to stage in London, the first event of its kind in England, she said, and Cunard referred her to Walrond. “As you know, he is a beautiful writer (prose, mainly), coloured, from the West Indies—a practiced journalist, able—charming too, and probably in touch with Negro talent in England.”22 Marx informed Walrond that in addition to running the press, she directed an arts organization, the Company of Nine, promoting poetry and the arts “in places where they are not so often to be found.” She asked if he “had any good ideas to offer on” a “Negro poetry programme” and whether he “thought it a good idea.”23 He could not have been more enthusiastic. “I do think your idea is a good one and I should be only too pleased to do whatever I can to help further it. It was very kind of Nancy Cunard to mention me to you.” He explained that although there had been comparable efforts on the radio, it was high time for what Marx proposed.

There have been discussions of Negro poetry and Negro poetry readings on the wireless, in particular during and immediately after the last war, but this was before coloured immigrants started coming into the United Kingdom in large numbers. Now that so many of them are here the venture which you have in mind would seem to fill a need and I can think of many places both in London and the provinces where a programme of Negro poetry with music would be sure to arouse enough interest and draw sufficiently large audiences to make the venture a sound one from a financial point of view. The bulk of the immigrants are concentrated at present in the Brixton area and the East End of London, Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, and Cardiff, and these are the localities which, I believe, audience response would be greatest.

Walrond felt that “the best Negro poetry (and the best known) is American,” but he believed the event ought to represent the African diaspora, especially because “the coloured immigrants in Great Britain are mostly West Indians and Africans.” Best to avoid “stirring chauvinist feelings,” he advised, and make the program “representative,” “a judicious mixture of American, West Indian, and Bantu poetry.” From the Caribbean, he suggested not only Anglophone verse but also “some of Nancy Cunard’s and Langston Hughes’ translations of Haytian and Cuban poetry.” The inquiry had fired Walrond’s imagination.24

He told Marx the idea was “not only a good one from an aesthetic point of view, but from the standpoint of race relations it is a highly commendable one.” He still believed in the power of literature to bridge the chasm between races and felt it was at least as wide in England as it was in the United States of the 1920s. “Believe it or not,” he told Jackman, “even the concept of Negro poetry is something that is disturbingly new to quite a lot of people I have met recently.”25 Nevertheless, he told Marx the target audience should not be white: “Am I thinking in terms of a mainly Negro audience to begin with? I’m afraid I am, and I assure you this won’t be a case of ‘carrying coals to New Castle.’”26 Even for black Britons, in other words, such a presentation would be revelatory. Walrond’s enthusiasm was matched by Marx, who thanked him “for replying so quickly and so lucidly and fully” to her inquiry. Before proceeding, however, she felt compelled to clarify a question provoked by his mailing address. “May I, at this point, ask you what your position in the hospital is? Somehow or other, I had taken it from Nancy Cunard’s letter that you were not a patient, but on the other hand maybe you are, and perhaps you would let me know.” She was impressed with his acumen; it was his sanity that concerned her.27 He settled the question by replying that he was a patient, but a voluntary one, and could “leave the hospital whenever I choose.” He mentioned his work in the community, perhaps to allay concerns about his fitness for work. He said, in effect, that he no longer needed hospitalization. “The interest which has been keeping me here is the work which I am at present doing on the ‘Roundway Review.’” Enclosing a copy of the latest issue, featuring The Second Battle, he said he hoped “fairly soon now to apply for my discharge.”28

He was right; within four months he moved to London, hopeful and content, thanks in part to the ameliorative effect of his work with Marx. But the London to which he returned had changed in his eighteen-year absence as much as he had. Despite the changes wrought by the Windrush generation, and despite some promising opportunities in the world of letters, Walrond would remain a struggling outsider through the end of his life there.

ric Walrond admitted himself to the Roundway Psychiatric Hospital after an unseasonably snowy spring. “South England Blizzard Chaos” read the local headline, and Walrond’s sun-drenched stories of Barbados, Guyana, and Panama accompanied him, unpublished, to his new home.1 The hospital, a massive complex on forty acres of land, housed thirteen hundred patients, many of whom were voluntary, like him. Formerly the Wiltshire County Asylum, it had been in operation since the Lunatics Act of 1845. For Walrond to acknowledge that he could no longer manage his illness required a good deal of courage and perhaps desperation. Patient records from this period were destroyed, but Walrond’s correspondence reveals the emotional stability and community he found there. Roundway was shabby and overcrowded but had practiced “a judicious combination of moral and therapeutic measures” since its inception.2 At a time when mechanical restraints and blunt coercion were still commonplace, the progressive Roundway staff believed patients recovered “by kindliness and vigilance, by ingenious arts of diversion and occupation.”3 A working farm, commissary, and laundry were staffed by patients, and a variety of clubs and activities kept them occupied. Teams competed in badminton and cricket against other hospitals. Walrond helped start a literary magazine, The Roundway Review.

ric Walrond admitted himself to the Roundway Psychiatric Hospital after an unseasonably snowy spring. “South England Blizzard Chaos” read the local headline, and Walrond’s sun-drenched stories of Barbados, Guyana, and Panama accompanied him, unpublished, to his new home.1 The hospital, a massive complex on forty acres of land, housed thirteen hundred patients, many of whom were voluntary, like him. Formerly the Wiltshire County Asylum, it had been in operation since the Lunatics Act of 1845. For Walrond to acknowledge that he could no longer manage his illness required a good deal of courage and perhaps desperation. Patient records from this period were destroyed, but Walrond’s correspondence reveals the emotional stability and community he found there. Roundway was shabby and overcrowded but had practiced “a judicious combination of moral and therapeutic measures” since its inception.2 At a time when mechanical restraints and blunt coercion were still commonplace, the progressive Roundway staff believed patients recovered “by kindliness and vigilance, by ingenious arts of diversion and occupation.”3 A working farm, commissary, and laundry were staffed by patients, and a variety of clubs and activities kept them occupied. Teams competed in badminton and cricket against other hospitals. Walrond helped start a literary magazine, The Roundway Review.