9

Birth defects and genetic disorders

The underlying etiologies of congenital anomalies and mechanisms by which they arise are shown in Table 9.1 and Figure 9.1. When confronted with a neonate with a congenital anomaly, there are a number of questions to ask (Table 9.2), features to look for (Table 9.3) and investigations to consider (Table 9.4). This evaluation process to establish a diagnosis is also appropriate when congenital anomalies are identified prenatally on antenatal ultrasound.

Table 9.1 Causes of congenital anomalies.

| Teratogenic | Environmental agents during pregnancy – infections, drugs (particularly anticonvulsants), alcohol and radiation |

| Sporadic or multifactorial | Many single birth defects occur as isolated cases with low recurrence risk. These may be polygenic or due to faults in developmental pathways |

| Single-gene disorders | May be family history or previous pregnancy losses. Many multiple malformation syndromes follow autosomal recessive inheritance, but consider X-linked recessive disorders in males and new dominant mutations in isolated cases |

| Chromosomal | Usually cause multiple congenital malformations and learning difficulties |

Fig. 9.1 Mechanisms of birth defects.

Chromosomal disorders

In addition to trisomy 21, 18 and 13 there are many hundreds of chromosomal deletions and rearrangements. Micro-array technology is increasingly able to detect them in fetal or neonatal DNA.

Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome)

Incidence is 1 in 650 live births. Most (94%) are due to non-disjunction of chromosome 21 during meiosis in the formation of eggs or sperm (Fig. 9.2). The risk increases with maternal age (Table 9.5) although most are born to mothers < 35 years old.

Fig. 9.2 Trisomy 21 due to non-disjunction.

Table 9.5 Risk of trisomy 21 in liveborn infants by maternal age.

| Maternal age at delivery (years) | Risk |

| All ages | 1 in 650 |

| 30 | 1 in 900 |

| 35 | 1 in 400 |

| 37 | 1 in 250 |

| 40 | 1 in 100 |

| 44 | 1 in 40 |

Approximately 5% are due to translocation, in which chromosome 21 is relocated onto another chromosome (usually onto chromosome 14). The risk of trisomy 21 is about 10% when the balanced translocation is carried by the mother. Most are identified prenatally. Non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) – free fetal DNA recovered from maternal serum in the late first trimester has 99.5% sensitivity for trisomy 21.

Clinical features

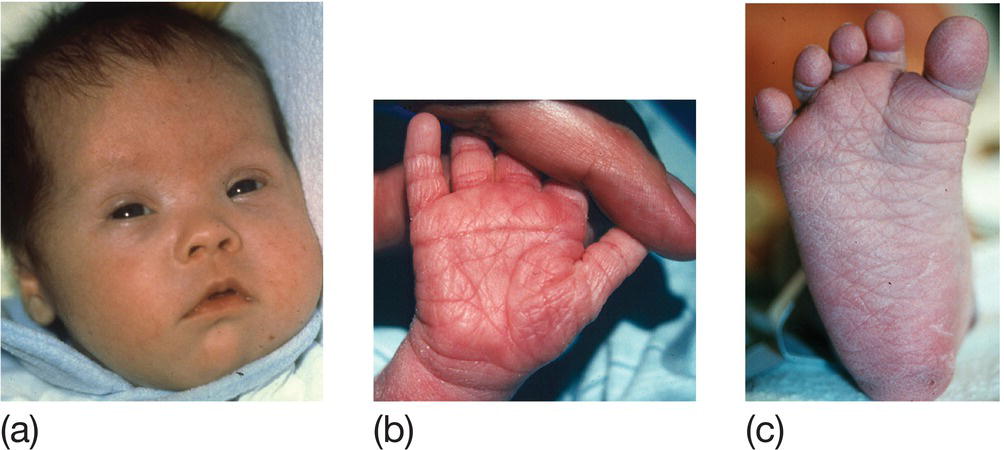

The facial appearance and other clinical signs (Fig. 9.3) are usually recognizable at birth but diagnosis needs to be confirmed by chromosome analysis. Associated malformations include congenital heart disease, duodenal atresia and Hirschsprung disease.

Fig. 9.3 Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome). (a) Facial features – upward slant of eyes, epicanthic folds, low set simple ears, flat occiput, third fontanel, short neck. (b) Hands – single palmar crease and short little finger. (c) Feet – wide gap between first and second toes. Other features – hypotonia.

Subsequently there is increased risk of:

- learning difficulties

- small stature

- secretory otitis media and visual impairment

- leukemia

- hypothyroidism

- Alzheimer disease.

Trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome)

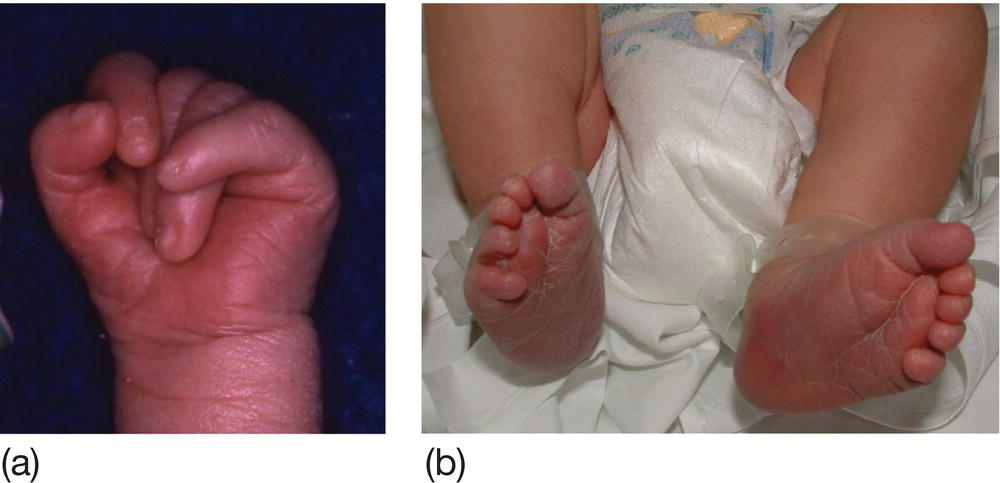

Incidence is 0.1/1000 live births. Most infants have intrauterine growth restriction. Dysmorphic features include prominent occiput, narrow forehead, small mouth and jaw, short sternum, clenched hands with overlapping digits (Fig. 9.4a), prominent heels and rocker-bottom feet (Fig. 9.4b). Major malformations include heart defects, neural tube defects, omphalocele, esophageal atresia and radial defects. Most die shortly after birth.

Fig. 9.4 Characteristic abnormalities of trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome). (a) Typical clenched hand with overlying digits. (b) Rocker-bottom feet.

Trisomy 13 (Patau syndrome)

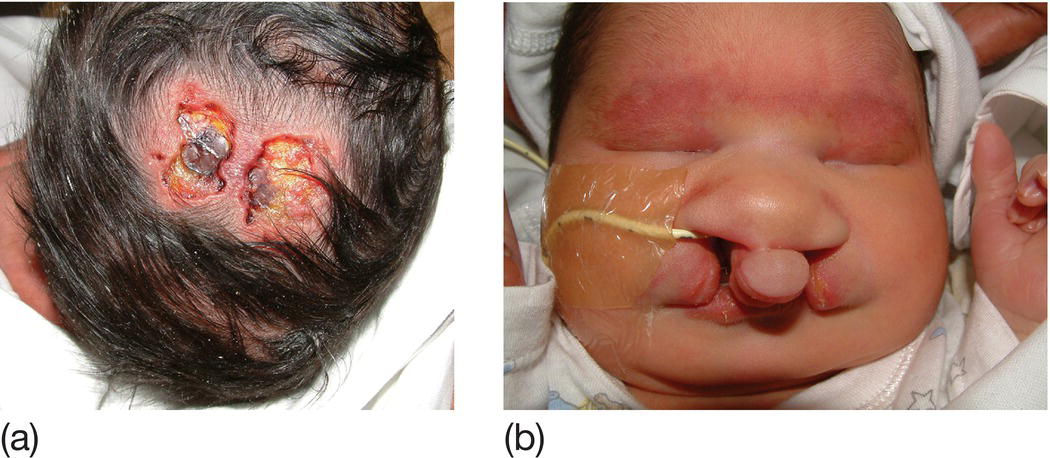

Incidence is around 0.7/1000 live births. Dysmorphic features include scalp defects (Fig. 9.5a) and polydactyly. Major malformations include holoprosencephaly (brain is a single hemisphere), microcephaly, ocular malformations, cleft lip and palate (Fig. 9.5b), heart defects and renal abnormality. Most babies die within 1 month.

Fig. 9.5 Characteristic abnormalities of trisomy 13 (Patau syndrome). (a) Scalp defect. (b) Cleft lip and palate.