36

Necrotizing enterocolitis

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is the most serious abdominal disorder of preterm infants. It occurs in 2–10% of VLBW (very low birthweight) infants and has a mortality of 15–25%.

The incidence increases with decreasing gestational age; it is rare in term infants. It is characterized by abdominal distension, bilious aspirates, bloody stools and intramural air (pneumatosis intestinalis) on abdominal X-ray.

There is inflammation of the bowel wall, which may progress to necrosis and perforation. It may involve a localized section of bowel (most often the terminal ileum) or be generalized.

It is usually sporadic but occasionally occurs in epidemics. In preterm babies the onset is usually at 1–2 weeks but may be up to several weeks of age. In term babies it occurs earlier, usually after an ischemic insult.

Risk factors

Pathogenesis is unknown, but several risk factors have been identified (Fig. 36.1). Exclusive feeding with human milk reduces the risk of NEC.

There is a change in the microbiome pattern in the gut preceding NEC (and late onset sepsis) revealing less diversity and changes in the community of gut microorganisms which become dominated by Proteobacteria and Firmicutes.

Fig. 36.1 Risk factors in the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis.

Clinical features

Onset is at 1–2 weeks but may be up to several weeks of age, with:

- bilious aspirates/vomiting

- feeding intolerance

- blood or mucus in stools

- abdomen – distension, distended veins, discoloration of the abdominal wall and tenderness (Fig. 36.2), which may progress to perforation (Table 36.1).

- features of sepsis – temperature instability, apnea and bradycardia, jaundice, lethargy, hypoperfusion and shock.

Fig. 36.2 Abdominal distension and shiny discolored, abdominal skin in severe necrotizing enterocolitis.

Table 36.1 Clinical signs of peritonitis/perforation.

| Abdominal tenderness |

| Guarding |

| Tense, discolored abdominal wall |

| Abdominal wall edema |

| Absent bowel sounds |

| Abdominal mass |

Laboratory findings

These include:

- raised acute-phase reactant (C-reactive protein (CRP), or procalcitonin)

- thrombocytopenia

- neutropenia, neutrophilia

- anemia

- blood culture positive

- coagulopathy

- metabolic acidosis

- hypoxia, hypercapnia

- hyponatremia, hyperkalemia

- increased BUN (blood urea nitrogen/urea)

- hyperbilirubinemia.

Radiologic abnormalities

- Dilated loops of bowel.

- Thickened intestinal wall.

- Inspissated stool (mottled appearance).

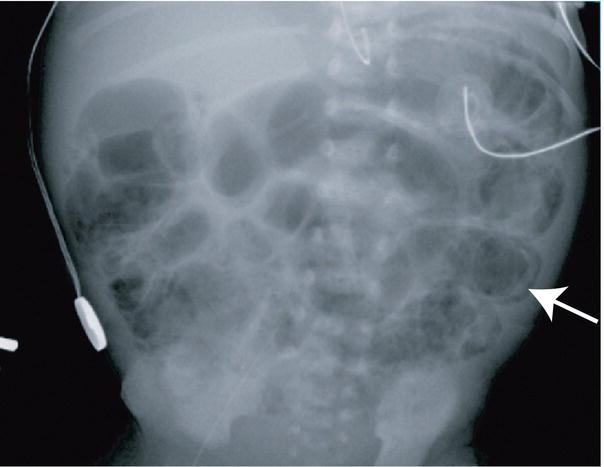

- Intramural air (pneumatosis intestinalis, pathognomonic sign) (Fig. 36.3).

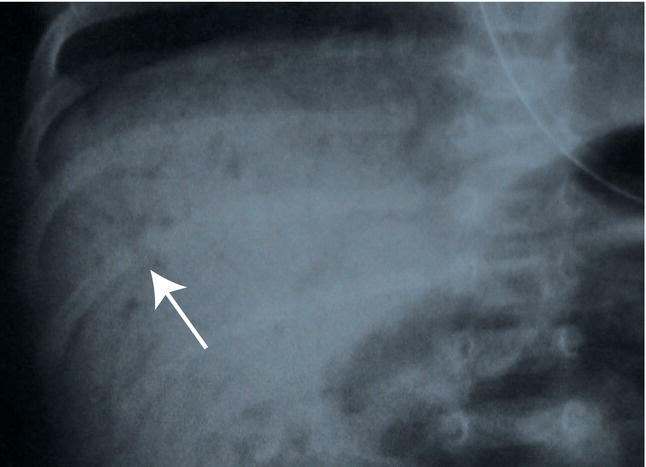

- Air in portal venous system (Fig. 36.4).

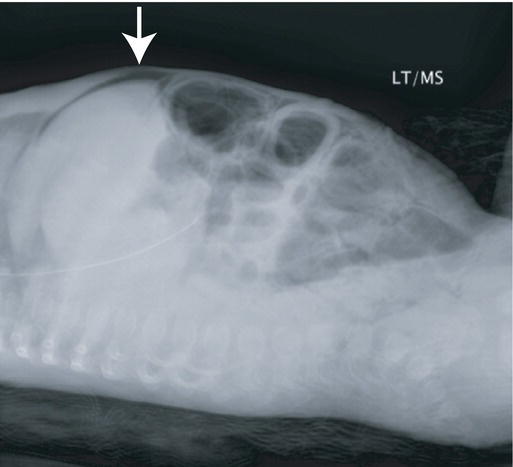

- Bowel perforation:

- – gasless abdomen/ascites

- – pneumoperitoneum

- – air below diaphragm/around the falciform ligament (Fig. 36.5).

Fig. 36.3 Abdominal X-ray showing dilated loops of bowel and intramural air (arrow).

(Courtesy of Dr Sheila Berlin.)

Fig. 36.4 Air in portal venous system (arrow). This is often a transient sign.

(Courtesy of Dr Annemarie Jeanes.)

Fig. 36.5 Bowel perforation showing air under the diaphragm on lateral x-ray (arrow).

(Courtesy of Dr Sheila Berlin.)

Management (Table 36.2)

Table 36.2 Management of necrotizing enterocolitis.

| Management | Rationale/goals |

| Secure airway and support breathing | Abdominal distension may compromise breathing |

| May require artificial ventilation | |

| Circulation | |

| Infusion of fluids |

| Treat hypoperfusion/hypovolemic shock |

| Improve organ and tissue perfusion |

| Place large-bore naso/orogastric tube | Intestinal decompression, bowel rest |

| NPO (nil by mouth) – start parenteral nutrition | Support nutritional demands for growth |

| Broad-spectrum antibiotics | Gram-positive, -negative and anaerobic coverage |

| Consider antifungal agents | |

| Treat coagulopathy (fresh frozen plasma, platelets, cryoprecipitate) | Avoid bleeding complications |

| Monitor regularly – clinical, radiographic and laboratory investigations | Necrotizing enterocolitis can worsen very quickly to bowel perforation |

Surgery – options are:

| Indications – bowel perforation or failure to resolve on medical treatment |

| However, peritoneal drainage alone is associated with worse neurodevelopmental outcome than laparotomy |

Sequelae

- Complications of prolonged parenteral nutrition – infection, electrolyte derangement, conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, etc.

Short bowel syndrome following bowel resection:

- Diarrhea (from loss of bowel mucosa and rapid gastrointestinal transit)

- Growth failure

- Vitamin B12 deficiency if terminal ileum resected

- Dependence on parenteral nutrition

- Stricture formation – causes intestinal obstruction and/or intestinal hemorrhage.

Prevention

- Use breast milk if possible.

- Avoid hyperosmolar feeds.

- Avoid rapid increase in feed volume in very immature infants, especially if intrauterine growth restriction with absent/reversed end-diastolic Doppler waveform antenatally.

- Probiotics with or without prebiotics and lactoferrin help maintain normal gut flora and may reduce risk of NEC.