50

Renal and urinary tract anomalies diagnosed prenatally

Most significant structural abnormalities of the kidneys and urinary tract are now identified prenatally on ultrasound screening. They account for 20–30% of all prenatally detected abnormalities. Early recognition and treatment may prevent or ameliorate complications such as urinary tract infection, failure to thrive and renal failure. When indicated, it may allow prenatal referral to a tertiary center. The disadvantage is that many minor or transient genitourinary anomalies are identified, resulting in unnecessary concern for the parents and additional investigations for the child.

Embryology

The kidneys and genitourinary tract are embryologically interdependent. If one system is abnormal, look for abnormalities of the other.

Structural abnormalities of the kidneys

Outflow obstruction

In the fetus with outflow obstruction (Fig. 50.1) there may be:

- hydronephrosis – unilateral or bilateral, with renal parenchyma that may be normal or malformed or dysplastic

- dilatation of the ureters and/or bladder

- reduced or absent amniotic fluid volume.

Fig. 50.1 Features of unilateral and bilateral outflow obstruction.

Unilateral hydronephrosis

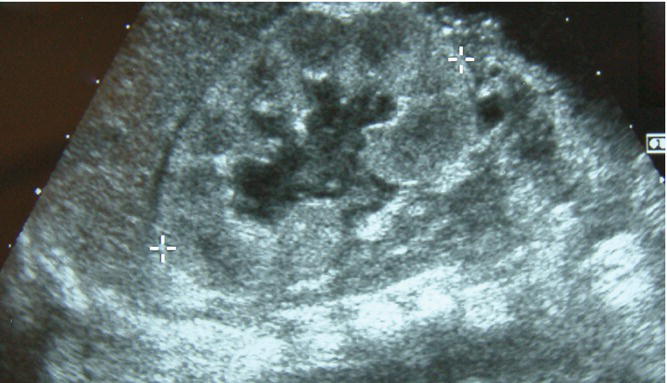

- Hydronephrosis is dilatation of the proximal collecting system (Fig. 50.2).

- It is the commonest abnormality diagnosed antenatally, and accounts for 50% of all prenatally detected urologic anomalies. It occurs in 1 in 500–700 infants. Most common cause is physiologic hydronephrosis, but others are obstruction at the pelviureteric or vesicoureteric junction or urinary reflux.

- Management is shown in Fig. 50.3.

- Most but not all resolve spontaneously. Prognosis is dependent on degree of kidney damage resulting from obstruction.

- If the anteroposterior diameter does not exceed 15 mm either antenatally or postnatally, intervention is rarely needed.

Fig. 50.2 Ultrasound showing unilateral hydronephrosis. As a measure of its severity, the anteroposterior renal pelvis diameter is measured.

(Courtesy of Dr Annemarie Jeanes.)

Fig. 50.3 Example of a guideline of the initial management of renal and urinary tract abnormalities detected on antenatal ultrasound.

Bilateral hydronephrosis

Less common than unilateral hydronephrosis but more likely to be serious.

Posterior urethral valves

- Mucosal folds or a membrane obstruct urine flow causing bilateral hydronephrosis, hydroureter and thickened bladder. One-third develop end-stage renal failure.

- Incidence is 1 in 5000–8000 live male births.

- Most are diagnosed on prenatal ultrasound, when antenatal intervention may be considered. Options include percutaneous vesicoamniotic shunt placement, bladder aspiration, and drainage of a severely distended kidney. However, outcome after intervention has been disappointing. As amniotic fluid is mainly derived from fetal urine, there may be severe oligohydramnios resulting in Potter syndrome/sequence (Fig. 50.4); the dominant features are from compression of the fetus and pulmonary hypoplasia resulting in stillbirth or early neonatal death.

- Presentation in the infant not diagnosed antenatally includes a palpable, distended bladder, poor urinary flow, renal and respiratory failure.

- Management postnatally is shown in Fig. 50.3. It is with prophylactic antibiotics, renal and urinary tract ultrasound within 24 hours of birth and VCUG (voiding cystourethrogram, micturating cystourethrogram, see Fig. 51.2).

- Treatment – drainage of the urinary tract, initially by urinary catheter, later by ablation of the valves. Careful fluid and electrolyte management.

Fig. 50.4 Potter syndrome (Potter sequence).

Polycystic kidney disease

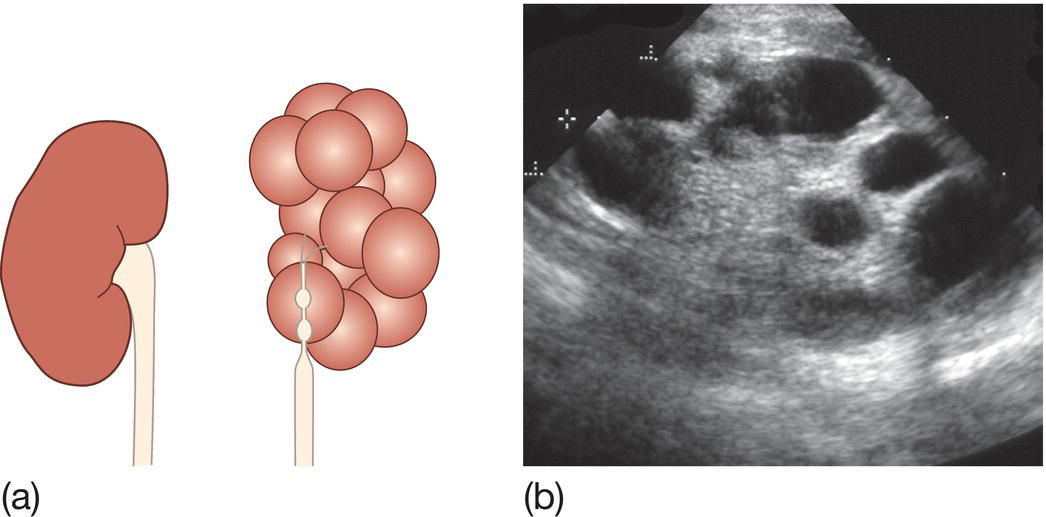

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) (Fig. 50.5a)

- Common: 1 in 500–1000 live births.

- Wide spectrum of severity; usually asymptomatic in childhood, causes renal failure in late adulthood.

- Extrarenal features: cysts in liver and pancreas, cerebral aneurysms and mitral valve prolapse.

Fig. 50.5 (a) Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). There are separate cysts of varying size between normal renal parenchyma. (b) Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD). There is diffuse bilateral enlargement of the kidneys.

Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD)

(Fig. 50.5b)

- Rare: 1 in 10 000–40 000 live births.

- Cysts form in the collecting duct.

- Neonates may present with pulmonary hypoplasia secondary to oligohydramnios (Potter syndrome/sequence, Fig. 50.4). May also present with abdominal masses, hypertension and renal failure.

- Associated with congenital hepatic fibrosis.

- May cause renal failure requiring renal transplant.

Multicystic dysplactic kidney (MCDK)

- Uncommon: 1 in 4000 live births.

- Renal parenchyma replaced by cysts of various sizes (Fig. 50.6a and b).

- Kidney is functionless, accompanied by atresia of the ureter.

- If bilateral, it leads to Potter syndrome/sequence.

- Kidney may be large and palpable, but more often is small. Contralateral kidney is usually normal, should have undergone compensatory hypertrophy, but at increased risk of vesicoureteric reflux.

- Half will have involuted by 2 years. Nephrectomy is only indicated if cysts increase in size or hypertension develops, both of which are rare.

Fig. 50.6 (a) Multicystic dysplastic kidney (MCKD). The kidney is replaced by cysts of variable size, with atresia of the ureter. (b) Renal ultrasound shows discrete cysts of variable size in multicystic dysplastic kidney (MCKD).

Renal agenesis

- Unilateral agenesis (present in 1 in 1000 live births) is only significant if the contralateral kidney is abnormal.

- Bilateral agenesis (Potter syndrome) is fatal from pulmonary hypoplasia due to severe oligohydramnios (Fig. 50.4).